Professional Documents

Culture Documents

University of North Carolina School of Law Prophets in Reverse by Brinkley

Uploaded by

Stacey Rowland0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views2 pagesUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Prophets in Reverse by Brinkley

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Prophets in Reverse by Brinkley

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views2 pagesUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Prophets in Reverse by Brinkley

Uploaded by

Stacey RowlandUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Prophets in Reverse by Brinkley

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Prophets in Reverse

MARTIN

H. BRINKLEY

The historian is a prophet in reverse.

-Friedrich von Schlegel

Some twelve years ago, the Harvard Law Review published a

comment examining the twenty diverse histories of American law

schools that had been published up to that time.' The authors of the

comment criticized the extant histories as exalting the Langdellian law

professor, and accused them of painting law schools as illiterate,

blundering backwaters before the gospel from Cambridge arrived in

the form of Harvard-educated faculty members. The "unilluminating

sameness"2 of these accounts, the authors seemed to feel, stemmed

in part from the sense that our school history "is not really a serious

form of scholarship,"' and in part from the seemingly inescapable

temptation of writing the history of the institution as a paean to the

professional law teacher. The cure to all this banality, according to

the Harvard critics, was to start viewing law students and teachers as

participants in a unique institution possessing a distinct social and

ideological character

I wish to record here my firm belief that these pages do indeed

portray the University of North Carolina School of Law as a unique

institution. The editors' decision to prepare this history from the

individual literary efforts of nearly a score of persons, all of them

more or less intimately connected to the law school, was made with

the goal of painting a vast mural in diverse styles-ultimately a truer

portrait of the school than any single individual could have created.

Doubtless some will fault the whole for its multifarious approaches.

Perhaps we have squandered a certain readability by declining to strip

each contribution of its individuality. Yet we have thought it best, on

1. Alfred S. Konefsky & John H. Schlegel, Comment, Mirror; Mirror on the Walk

Historiesof American Law Schools, 95 HARv. L. Rav. 833 (1982).

2. Id. at 839.

3. Id at 843.

4. See id at 847-51.

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 73

the whole, to encourage the contributors to speak in their own voices,

even as every member of the law school community is, we believe,

encouraged to speak personally of her communion with the

institution. We hope you will agree that, with such an end in view,

certain small sacrifices were justified.

A harmless pleasure of this work has been my growing, and

ultimately overwhelming, conviction that the University of North

Carolina School of Law has given the lie to Emerson. It was he, after

all, who thought that institutions were reducible to "the lengthened

shadow of one man."5 If this history does nothing else, it surely

shows that our law school and University are no single human being's

intellectual or personal progeny. Unlike our sister in Charlottesville,

we do not owe our conception to a father who emblazoned on us the

vast sweep and thundering power of his own magnificent brain. We

are the child of a whole people: the people of North Carolina. Their

mark is upon us everywhere we turn, but we must look to find it-it

does not leap out as a particular building designed in a favored style,

or as a single dominating name or principle. I have always thought

it significant that statues are not a prominent feature of our University or School of Law. It is not the cudgel of a single personality or

group that we feel, but an inward strain of spiritual beauty that

cannot be seen. I believe that inward strain is a history and destiny

of intellectual freedom.

Like Athens was to Greece and Rome, our University and law

school are an education to North Carolina. They have done much to

enable our citizens to express themselves with grace and confidence.

They do not seek distorted praises or exaggerated themes; they only

require an estimation of the facts that will enable the people of North

Carolina to gauge their true worth. To this goal the editors of and

contributors to this history have pledged themselves. In this sense we,

the chroniclers, are, indeed, prophets in reverse.

5. RALPH W. EMERSON, Self-Reliance, in ESSAYS: FIRST SERIES 35 (The Belknap

Press of Harvard Univ. Press 1979) (1841).

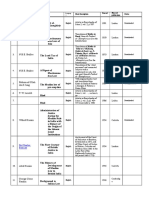

You might also like

- Romantics at War: Glory and Guilt in the Age of TerrorismFrom EverandRomantics at War: Glory and Guilt in the Age of TerrorismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Black Space: Negotiating Race, Diversity, and Belonging in the Ivory TowerFrom EverandBlack Space: Negotiating Race, Diversity, and Belonging in the Ivory TowerNo ratings yet

- Imaginary Betrayals: Subjectivity and the Discourses of Treason in Early Modern EnglandFrom EverandImaginary Betrayals: Subjectivity and the Discourses of Treason in Early Modern EnglandNo ratings yet

- The U.S. Immigration Crisis: Toward an Ethics of PlaceFrom EverandThe U.S. Immigration Crisis: Toward an Ethics of PlaceNo ratings yet

- Legal Intellectuals in Conversation: Reflections on the Construction of Contemporary American Legal TheoryFrom EverandLegal Intellectuals in Conversation: Reflections on the Construction of Contemporary American Legal TheoryNo ratings yet

- The Rites of Identity: The Religious Naturalism and Cultural Criticism of Kenneth Burke and Ralph EllisonFrom EverandThe Rites of Identity: The Religious Naturalism and Cultural Criticism of Kenneth Burke and Ralph EllisonNo ratings yet

- The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity During the Hundred Years WarFrom EverandThe Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity During the Hundred Years WarNo ratings yet

- Erotic Citizens: Sex and the Embodied Subject in the Antebellum NovelFrom EverandErotic Citizens: Sex and the Embodied Subject in the Antebellum NovelNo ratings yet

- The Signers of the Declaration of Independence: Biographies: Including the Constitution of the United States and Other Decisive Historical DocumentsFrom EverandThe Signers of the Declaration of Independence: Biographies: Including the Constitution of the United States and Other Decisive Historical DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Acts of Hope: Creating Authority in Literature, Law, and PoliticsFrom EverandActs of Hope: Creating Authority in Literature, Law, and PoliticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Quiet Testimony: A Theory of Witnessing from Nineteenth-Century American LiteratureFrom EverandQuiet Testimony: A Theory of Witnessing from Nineteenth-Century American LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Legal Realism to Law in Action: Innovative Law Courses at UW-MadisonFrom EverandLegal Realism to Law in Action: Innovative Law Courses at UW-MadisonNo ratings yet

- Blowing Clover, Falling Rain: A Theological Commentary on the Poetic Canon of the American ReligionFrom EverandBlowing Clover, Falling Rain: A Theological Commentary on the Poetic Canon of the American ReligionNo ratings yet

- White by Law 10th Anniversary Edition: The Legal Construction of RaceFrom EverandWhite by Law 10th Anniversary Edition: The Legal Construction of RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- English Literature and Religion 1800-1900 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandEnglish Literature and Religion 1800-1900 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- In Praise of Prometheus: Humanism and Rationalism in Aeschylean ThoughtFrom EverandIn Praise of Prometheus: Humanism and Rationalism in Aeschylean ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Neighbors and Strangers: Law and Community in Early ConnecticutFrom EverandNeighbors and Strangers: Law and Community in Early ConnecticutNo ratings yet

- By Birth or Consent: Children, Law, and the Anglo-American Revolution in AuthorityFrom EverandBy Birth or Consent: Children, Law, and the Anglo-American Revolution in AuthorityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Even When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationFrom EverandEven When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationNo ratings yet

- The Vision of the Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in the Western TraditionFrom EverandThe Vision of the Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in the Western TraditionNo ratings yet

- Arthur Balfour's Ghosts: An Edwardian Elite and the Riddle of the Cross-Correspondence Automatic WritingsFrom EverandArthur Balfour's Ghosts: An Edwardian Elite and the Riddle of the Cross-Correspondence Automatic WritingsNo ratings yet

- In the Courts of the Conquerer: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever DecidedFrom EverandIn the Courts of the Conquerer: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever DecidedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the LawFrom EverandHiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the LawRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Mirror, Mirror: The Uses and Abuses of Self-LoveFrom EverandMirror, Mirror: The Uses and Abuses of Self-LoveRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- An Address, Delivered Before the Was-ah Ho-de-no-son-ne or New Confederacy of the Iroquois: Also, Genundewah, a PoemFrom EverandAn Address, Delivered Before the Was-ah Ho-de-no-son-ne or New Confederacy of the Iroquois: Also, Genundewah, a PoemNo ratings yet

- Recent Tendencies in Ethics: Three Lectures to Clergy Given at CambridgeFrom EverandRecent Tendencies in Ethics: Three Lectures to Clergy Given at CambridgeNo ratings yet

- Dislocating Race and Nation: Episodes in Nineteenth-Century American Literary NationalismFrom EverandDislocating Race and Nation: Episodes in Nineteenth-Century American Literary NationalismNo ratings yet

- The Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Complete Biographies in One Volume: Including the Constitution of the United States, Washington's Farewell Address, Articles of Confederation, The Declaration of Independence as originally written by Thomas Jefferson and Other DocumentsFrom EverandThe Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Complete Biographies in One Volume: Including the Constitution of the United States, Washington's Farewell Address, Articles of Confederation, The Declaration of Independence as originally written by Thomas Jefferson and Other DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular TheoryFrom EverandBlues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular TheoryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (5)

- The Sublime of the Political: Narrative and Autoethnography as TheoryFrom EverandThe Sublime of the Political: Narrative and Autoethnography as TheoryNo ratings yet

- Literary Critical Theory and The English Education SpecialistDocument8 pagesLiterary Critical Theory and The English Education Specialistsanjay dasNo ratings yet

- The American Idea: The Literary Response to American OptimismFrom EverandThe American Idea: The Literary Response to American OptimismNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of the Self: Sexuality, Self-Knowledge, and the Gaze in the Early Roman EmpireFrom EverandThe Mirror of the Self: Sexuality, Self-Knowledge, and the Gaze in the Early Roman EmpireNo ratings yet

- Transfiguration: Poetic Metaphor and the Languages of Religious BeliefFrom EverandTransfiguration: Poetic Metaphor and the Languages of Religious BeliefNo ratings yet

- The Death of Learning: How American Education Has Failed Our Students and What to Do about ItFrom EverandThe Death of Learning: How American Education Has Failed Our Students and What to Do about ItRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Priest, Prophet, Pilgrim: Types and Distortions of Spiritual Vocation in the Fiction of Wendell Berry and Cormac McCarthyFrom EverandPriest, Prophet, Pilgrim: Types and Distortions of Spiritual Vocation in the Fiction of Wendell Berry and Cormac McCarthyNo ratings yet

- After Emancipation: Racism and Resistance at the University of VirginiaFrom EverandAfter Emancipation: Racism and Resistance at the University of VirginiaNo ratings yet

- Comics and Sacred Texts: Reimagining Religion and Graphic NarrativesFrom EverandComics and Sacred Texts: Reimagining Religion and Graphic NarrativesAssaf GamzouNo ratings yet

- A Discourse Upon the Origin and the Foundation of the Inequality Among MankindFrom EverandA Discourse Upon the Origin and the Foundation of the Inequality Among MankindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (200)

- Reading Character after Calvin: Secularization, Empire, and the Eighteenth-Century NovelFrom EverandReading Character after Calvin: Secularization, Empire, and the Eighteenth-Century NovelNo ratings yet

- The Kinship Wars: An Essay on the Prehistory of Social AnthropologyFrom EverandThe Kinship Wars: An Essay on the Prehistory of Social AnthropologyNo ratings yet

- Area Studies in the Global Age: Community, Place, IdentityFrom EverandArea Studies in the Global Age: Community, Place, IdentityEdith ClowesNo ratings yet

- BACKHOUSE, Constance. Gender and Race in The Construction of Legal Professionalism - Historical Perspectives PDFDocument26 pagesBACKHOUSE, Constance. Gender and Race in The Construction of Legal Professionalism - Historical Perspectives PDFHeloisaBianquiniNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Sun Mar 5 1950 (CPU Roundtable Segreg Ed)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Sun Mar 5 1950 (CPU Roundtable Segreg Ed)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- Daily Tar Heel Fri Sep 28 1951 Segregation at GameDocument1 pageDaily Tar Heel Fri Sep 28 1951 Segregation at GameStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The High Point Enterprise Sat Jun 9 1951Document1 pageThe High Point Enterprise Sat Jun 9 1951Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Fri Sep 28 1951 (Editorial)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Fri Sep 28 1951 (Editorial)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Fri Mar 23 1951Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Fri Mar 23 1951Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Sat Sep 23 1950Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Sat Sep 23 1950Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- Mississippi Foreclosure Avoidance Manual, 2007 Gary A. RowlandDocument98 pagesMississippi Foreclosure Avoidance Manual, 2007 Gary A. RowlandStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Dec 5 1950 (Tenn Defy CT)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Dec 5 1950 (Tenn Defy CT)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Fri Jul 10 1951 (No Admit Other Grad School p1)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Fri Jul 10 1951 (No Admit Other Grad School p1)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 12 1951 (4 Negros Now at Law p1)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 12 1951 (4 Negros Now at Law p1)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 19 1951 (Walker Admitted)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 19 1951 (Walker Admitted)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 12 1951 (Full Page)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Jun 12 1951 (Full Page)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed Mar 21 1951 (New Negro Admit Policy MTG)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed Mar 21 1951 (New Negro Admit Policy MTG)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed Jan 24 1951 (News 4th Cir Appeal)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed Jan 24 1951 (News 4th Cir Appeal)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed Apr 4 1951 (Trustees and Debate Soc On Negro Admission)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed Apr 4 1951 (Trustees and Debate Soc On Negro Admission)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Fri Jul 10 1951 (No Admit Other Grad School p2)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Fri Jul 10 1951 (No Admit Other Grad School p2)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling Reaction (Cont)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling Reaction (Cont)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling New Pres ReactionDocument1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling New Pres ReactionStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- Daily - Tar - Heel - Oct - 19 - 1937 (Clip - Debate Topic Accept Negroes in Law School)Document1 pageDaily - Tar - Heel - Oct - 19 - 1937 (Clip - Debate Topic Accept Negroes in Law School)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Sun Mar 9 1952 (Harrassment Charged)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Sun Mar 9 1952 (Harrassment Charged)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Sun Oct 7 1951 Segregated Seats at GameDocument1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Sun Oct 7 1951 Segregated Seats at GameStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling ReactionDocument1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Tue Oct 10 1950 Hayes Ruling ReactionStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Times News Jan 1948 (OK Protests)Document1 pageThe Daily Times News Jan 1948 (OK Protests)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed Oct 26 1949Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed Oct 26 1949Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- University of North Carolina School of Law Observation and Overview by WegnerDocument2 pagesUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Observation and Overview by WegnerStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed May 11 1949 (Epps Talk)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed May 11 1949 (Epps Talk)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Wed May 12 1948 (Poll Favors Negros at Law School)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Wed May 12 1948 (Poll Favors Negros at Law School)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel Thu Aug 25 1949 (NAACP Suits Planned)Document1 pageThe Daily Tar Heel Thu Aug 25 1949 (NAACP Suits Planned)Stacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- University of North Carolina School of Law Vietnam Era by AycockDocument21 pagesUniversity of North Carolina School of Law Vietnam Era by AycockStacey RowlandNo ratings yet

- Summary of Habermas's TCADocument21 pagesSummary of Habermas's TCAestifanostzNo ratings yet

- Subculture and Counterculture Skit: One OneDocument2 pagesSubculture and Counterculture Skit: One OneGuillermo CoreaNo ratings yet

- SEVEN TYPES OF MEANINGDocument61 pagesSEVEN TYPES OF MEANINGVŨ KIÊNNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument18 pagesNew Text DocumentKiné Therapeut-manuelle Masseur GabiNo ratings yet

- Personal Writing Process Essay Austinbarger Final 1Document5 pagesPersonal Writing Process Essay Austinbarger Final 1api-374592609No ratings yet

- TEAM 252A: The Case Concerning The Sisters of The SunDocument52 pagesTEAM 252A: The Case Concerning The Sisters of The SunKevin joseph100% (2)

- Education PsychologyDocument29 pagesEducation PsychologyMAM COENo ratings yet

- Glossary of Linguistic TermsDocument12 pagesGlossary of Linguistic TermsMarciano Ken HermieNo ratings yet

- Cpar ReviewerDocument5 pagesCpar ReviewerJulian AlbaNo ratings yet

- GamabaDocument29 pagesGamababachillerjanica55No ratings yet

- Write Up Newsletter p1Document5 pagesWrite Up Newsletter p1api-378872280No ratings yet

- Inson, Rizel Jane AdvocacyDocument2 pagesInson, Rizel Jane Advocacyjey jeydNo ratings yet

- Calcos Lingüísticos y Lraseológicos en El Lenguaje AudiovisualDocument315 pagesCalcos Lingüísticos y Lraseológicos en El Lenguaje AudiovisualAdrianaSica100% (1)

- Ideologies of The Axis PowersDocument9 pagesIdeologies of The Axis PowersDoctor HudsonNo ratings yet

- Indicatror BrownDocument22 pagesIndicatror BrownBinkei TzuyuNo ratings yet

- Artists and ArtisansDocument46 pagesArtists and ArtisansKathlene Cagas100% (2)

- Beginner Mandarin Chinese Tests Greetings Numbers DatesDocument8 pagesBeginner Mandarin Chinese Tests Greetings Numbers Datessburger78No ratings yet

- Occultist Michael BertiauxDocument3 pagesOccultist Michael BertiauxEneaGjonajNo ratings yet

- Lozano-Adrian-Assignment 2 RecruitmentDocument2 pagesLozano-Adrian-Assignment 2 RecruitmentFrancisco AdrianNo ratings yet

- Social Stratification Chapter 8Document14 pagesSocial Stratification Chapter 8pri2shNo ratings yet

- First Year Academics: Criterion 8Document12 pagesFirst Year Academics: Criterion 8kubera u100% (2)

- Kundalini Mahashakti Aur Usaki Sansiddhi PDFDocument105 pagesKundalini Mahashakti Aur Usaki Sansiddhi PDFdimitriNo ratings yet

- Studying The State Through State Formation: by Tuong VuDocument28 pagesStudying The State Through State Formation: by Tuong VuRobin EkelundNo ratings yet

- Suggested Parent Interview GuideDocument5 pagesSuggested Parent Interview GuidePaulojoy Buenaobra0% (1)

- Sociol AQA A2 Unit 4 Workbook AnswersDocument58 pagesSociol AQA A2 Unit 4 Workbook AnswersSkier MishNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan SituationalDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Situationalafrasayab mubeenaliNo ratings yet

- Christine E. TulleyDocument13 pagesChristine E. TulleyChristine TulleyNo ratings yet

- How To Raise Successful KidsDocument122 pagesHow To Raise Successful KidsOana Calugar100% (3)

- Islamic Legal Texts DatabaseDocument13 pagesIslamic Legal Texts DatabaseJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- STAN Apr-June 2012Document72 pagesSTAN Apr-June 2012A_Sabedora_GataNo ratings yet