Professional Documents

Culture Documents

040601using Judgement To Improve Accuracy in Decision Making

Uploaded by

Yosdim Si SulungOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

040601using Judgement To Improve Accuracy in Decision Making

Uploaded by

Yosdim Si SulungCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL

ADVANCED

Using judgement to improve

accuracy in decision-making

Benner, P. et al (1999) Clinical Wisdom

and Interventions in Critical Care.

Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders.

Benner, P. et al (1992) From beginner

to expert: gaining a differentiated

clinical world in critical care nursing.

Advances in Nursing Science; 14: 3,

1328.

Cioffi, J. (1997) Heuristics, servants

to intuition, in clinical decision-making.

Journal of Advanced Nursing;

1997: 26, 203208.

Cioffi, J. (2002) What are clinical

judgements? In: Thompson, C.,

Dowding, D. (eds) Clinical decisionmaking and judgement in nursing.

Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Corcoran, S.A. (1986) Task Complexity

and nursing expertise as factors

in decision-making. Nursing Research;

35: 2, 107112.

Dowding, D. (2002) Interpretation of

risk and social judgement theory. In:

Thompson, C., Dowding, D. (eds)

Clinical decision-making and

judgement in nursing. Edinburgh:

Churchill Livingstone.

Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2004)

Using decision trees to aid decisionmaking in nursing. Nursing Times;

100: 21, 3639.

42

This is the third of four papers discussing judgement and

decision-making in nursing. The first paper in this series

(Thompson et al, 2004) highlighted the importance of

judgement and decision-making to nursing practice. The

second (Dowding and Thompson, 2004) discussed how

complexity associated with decision problems could be

made sense of by using an approach to structuring decisions known as decision analysis. The aim of this article

is to discuss the issue of judgement in nursing. In particular, it examines the way nurses may use information

to inform their judgements, and ways in which this process can be assisted to improve the accuracy of judgements.

Judgement in nursing

The process of judgement involves integrating different

aspects of information (which may be about a person,

object or situation) to arrive at an overall evaluation

(Maule, 2001). In nursing this could be considered as the

process of using different types of clinical information

about the patient (such as appearance, vital signs, and

behaviour) to make an assessment of her or his current

health status (Dowding and Thompson, 2003).

Judgements feed into decision-making (Box 1) in that

the evaluations or assessments an individual makes can

be used as the basis of choice between alternatives. For

example a nurse may assess a patient as being at risk

of developing a pressure ulcer (judgement) and then

choose a particular intervention to reduce that risk

BOX 1. DEFINING JUDGEMENT AND DECISION

JUDGEMENTS

DECISIONS

Generally considered

to be assessments,

estimates or

predictions of an entity

(Harvey, 2001)

Generally considered to

be opposed to decisions,

which are considered

to be a choice

between alternatives

(Dowie, 1993).

(decision) on the basis of the assessment.

Examining judgements in nursing is important, as they

have an effect on decisions taken about patient care.

Harvey (2001) suggests decisions may be poor because

the judgements on which they depend are inaccurate or

because individuals combine different judgements inappropriately. Therefore, a key issue for nurses and patients

is ensuring judgements are as accurate as possible.

There are two main reasons for inaccuracy:

The nurse may be using information that has no utility

for the judgement in question (Cioffi 2002);

The nurse may be placing too much importance on

particular information (Dowding, 2002).

Therefore, the type of information individuals use to

inform their judgements, some knowledge of the information they should be using to inform their judgements,

and how that information is (or should be) combined is

required to investigate and improve accuracy. The two

main ways these issues have been investigated are

descriptive research and social judgement analysis.

Descriptive research into judgement

Most of the research examining judgement in nursing is

qualitative and descriptive in nature an appropriate

design for the research questions being addressed. The

aim of many of the studies is to describe the nature of

judgements through the analysis of how nurses manage

clinical situations, including the information they use to

inform their judgements and decisions.

The use of intuition and rules

Perhaps the most well known research in this area is that

carried out by Benner et al (Benner, et al 1999; 1992;

Benner, 1982). This research highlighted characteristics

of expert nursing practice and judgement and how that

expertise develops. Benner (1982) suggests expert

nurses mainly use intuition, which is defined as knowing

without necessarily having a specific rationale or making

explicit all that goes into ones sense of a situation

NT 1 June 2004 Vol 100 No 22 www.nursingtimes.net

Alamy

REFERENCES

Benner, P. (1982) From Novice to

Expert. American Journal of Nursing;

82: 402407.

AUTHORS Dawn Dowding, PhD, RN, is senior lecturer,

Hull York Medical School, University of York; Carl

Thompson, DPhil, RN, is senior research fellow,

Department of Health Sciences, University of York.

ABSTRACT Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2004) Using

judgement to improve accuracy in decision-making.

Nursing Times; 100: 22, 4244.

Nursing judgements are complex, often involving the

need to process a large number of information cues. Key

issues include how accurate they are and how we can

improve levels of accuracy. Traditional approaches to the

study of nursing judgement, characterised by qualitative

and descriptive research, have provided valuable insights

into the nature of expert nursing practice and the complexity of practice. However, they have largely failed to

provide the data needed to address judgement accuracy.

Social judgement analysis approaches are one way of

overcoming these limitations. This paper argues that as

nurses take on more roles requiring accurate judgement,

it is time to increase our knowledge of judgement and

ways to improve it.

KEYWORDS

(Benner, 1999).

This is in direct contrast to less experienced individuals

who may use rules to combine common attributes such

as a patients vital signs (Benner, 1982). This combination may eventually be combined into some form of

global pattern that guides action.

Although Benners work has provided insight into the

nature of expert nursing practice, it fails to give details of

how information is processed to inform accurate judgements. This is due in part to the research methods used

predominantly observation of practice and interviews.

However, observation cannot provide insight into all

the information used in reaching a judgement, and selfreporting has been shown to be an unreliable method of

investigating judgement and decision-making as individuals often have little insight into how they make

judgements and decisions (Harries et al, 1996). Also, the

critical incident method used by Benner et al (1999) may

mean individuals only examine situations where their

reasoning processes have been successful (Lamond and

Thompson, 2000), meaning a full exploration of issues of

judgement accuracy is not possible.

Information processing

Another set of studies used the psychological theory of

information processing (Newell and Simon, 1972) as the

basis for exploring the reasoning processes nurses use

when making judgements and decisions. This theory

suggests humans have limited capacity for processing

information, meaning a variety of strategies is employed

to assist the process. Examples of this type of study have

been carried out by Cioffi (1997), Tanner et al (1987),

and Corcoran (1986). These studies have suggested that

nurses use a process of hypothetico-deductive reasoning

when making judgements, together with mental short

cuts or heuristics.

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning involves using available information to formulate hypotheses, which are

then tested and reformulated until a conclusion is

reached (Thompson and Dowding, 2002). The types of

information that appear to be used vary considerably. For

instance in a very early study examining the information

nurses use to make a judgement about patient pain,

Hammond et al (1966) found they used 165 different

information cues. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

appears to be used by individuals in situations where

they have no experience of the task in question. In situations where people have more experience, they are

more likely to use a process of pattern matching, which

involves the recognition of similarities between the

patient case being considered and ones that have been

encountered in the past (Elstein et al, 1990). These short

cuts are the focus of the fourth paper in this series.

The main strategies used to examine reasoning and

information use in information processing studies are

variations of a think aloud technique and retrospective

interviewing (Tanner et al, 1987; Corcoran, 1986).

Simulations are typically used to compare individuals

across cases. The process of thinking aloud involves the

NT 1 June 2004 Vol 100 No 22 www.nursingtimes.net

Education Decision-making Judgement

subject of the study verbalising everything they think of

while carrying out the judgement task. They may be

interviewed after the task to discuss any other information they think they used and their rationale.

There are a number of problems with this type of

study: the use of simulations may mean the judgements

made by the subject do not reflect what they would do

with a patient. Also, thinking aloud relies on the participants ability to make their judgement policies explicit

(Harries and Harries, 2001), and retrospective interviewing suffers from the same problems as highlighted above.

Limitations of descriptive research

In summary, if we are interested in the accuracy of

judgements, much of the descriptive research into nursing practice fails to provide the evidence that is needed

to inform practice. These types of study are a useful representation of practice but it is difficult to observe a sufficient range of scenarios for a given judgement in order

to determine how information is used to make that

judgement (Harries and Harries, 2001).

Many of the studies look at a broad range of practice,

which means detail about the information cues is often

lacking. Also, a reliance on self-report methods (such as

interviews and thinking aloud) means the research is

dependent on a participants insight into her or his judgement processes and ability to verbalise these processes.

By definition expert judgement usually involves the

use of automatic, unconscious thought processes (often

referred to as intuition). Such experts often will not be

able to verbalise their thoughts a characteristic that

limits the analysis of their judgements (Lamond and

Thompson, 2000).

Social judgement analysis

The lens model

The theoretical basis of social judgement analysis is the

lens model of cognition proposed by Brunswik. This is a

representation of the relationship between a person and

her or his environment (Harries and Harries, 2001).

Brunswik suggested that to investigate judgement,

researchers should take into account the unpredictable

nature of the environment in which they operate, and

that a range of judgements, in a range of situations,

needs to be investigated (Harries and Harries, 2001).

The lens model can be represented diagrammatically

(Fig 1). In this diagram the left-hand side represents the

environment (such as a patients state of health). A

number of different information cues will be related

probabilistically to this environment. The right-hand side

represents the individual making the judgement. This

person uses information cues to make her or his judgement on the environment (for example, do I need to call

a doctor?) and in doing so will attach more weight to

some cues than others. By comparing the way the information cues are related to the state in the environment

and the weighting assigned to information cues by the

judge, one can identify:

If the persons judgement is accurate (is there a corre-

REFERENCES

Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2003)

Measuring the quality of judgement and

decision-making in nursing. Journal of

Advanced Nursing; 44: 1, 4957.

Dowie, J. (1993) Clinical decision

analysis: Background and introduction.

In: Llewelyn, H., Hopkins, A. (eds)

Analysing How we Reach Clinical

Decisions. London: Royal College of

Physicians.

Elstein, A.S. et al (1990) Medical

problem solving: a ten-year

retrospective. Evaluation and the

Health Professions; 13: 1, 536.

Hammond, K.R. et al (1966) Clinical

inference in nursing: use of informationseeking strategies by nurses. Nursing

Research; 15: 4, 330336.

Harries, C. et al (1996) A clinical

judgement analysis of prescribing

decisions in general practice. Le Travail

Humain; 59: 1, 87111.

Harries, P.A., Harries, C. (2001)

Studying clinical reasoning. Part 2:

Applying social judgement theory.

British Journal of Occupational

Therapy; 64: 6, 285292.

Harvey, N. (2001) Studying judgement:

general issues. Thinking and

Reasoning; 7: 1, 103118.

Lamond, D., Thompson, C. (2000)

Intuition and analysis in decisionmaking and choice. Journal of Nursing

Scholarship; 32: 3, 411414.

Maule, A.J. (2001) Studying judgement:

some comments and suggestions for

future research. Thinking and

Reasoning; 7: 1, 91102.

This article has been double-blind

peer-reviewed.

For related articles on this subject

and links to relevant websites see www.

nursingtimes.net

43

ADVANCED

REFERENCES

Newell, A., Simon, H.A. (1972)

Human Problem Solving. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Accuracy

X1

Skanr, Y. et al (2000) The use of

clinical information in diagnosing

chronic heart failure: a comparison

between general practitioners,

cardiologists, and students.

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology;

53: 10811088.

Tanner, C.A. et al (1987) Diagnostic

reasoning strategies of nurses and

nursing students. Nursing Research;

36: 6, 358363.

Thompson, C. et al (2004) Strategies for

avoiding pitfalls in clinical decisionmaking. Nursing Times; 100: 20, 4042.

Thompson, C., Dowding, D. (2002)

Decision-making and judgement in

nursing an introduction. In: Thompson,

C., Dowding, D. (eds) Clinical DecisionMaking and Judgement in Nursing.

Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Wigton, R.S. (1996) Social judgement

theory and medical judgement.

Thinking and Reasoning;

2: 2 175190.

SERIES ON CLINICAL DECISION-MAKING

This is the third in a four-part

series on decision-making:

1. Strategies for avoiding the pitfalls in

clinical decision-making

2. Using decision trees to

structure clinical decisions

3. How to use information cues

accurately when making clinical

decisions;

4. Tools for handling information

in clinical decision-making.

44

Cognitive feedback

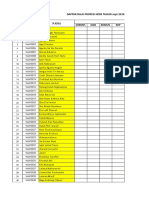

FIG1. THE LENS MODEL

Cues

X2

X3

True state

Judged

Correct

weights

X4

Judges

weights

spondence between patient state and the judgement?);

Whether the judge uses appropriate information, and if

so, does she or he put appropriate importance or weighting on different pieces of information (Dowding, 2002).

Disagreement between judges

Using this model highlights where disagreements occur

between judges: they could be using different information or be placing different importance on certain cues,

which would lead to differences in judgements.

In order to model the environment statistical techniques are used to identify possible relationships

between information and a patient state. For instance, in

a study examining doctors diagnoses of heart failure,

Skanr et al (2000) used information from patient cases

to model how different cues were related to the diagnosis. This optimal strategy suggested cardiac enlargement was the most important cue to determine if a

patient had heart failure. To model the clinicians judgement, a number of scenarios of patient cases are constructed containing information considered important for

the judgement under investigation, and designed to

represent the range of situations in the environment.

Judging scenarios

In social judgement analysis studies, the number of scenarios is often very large to make the judgements as real

as possible (Harries and Harries, 2001). The judge(s) are

then asked to make a judgement about each of the scenarios, and this is then also modelled using statistical

techniques (usually of linear multiple regression). This

provides a statistical analysis of the information the

judge uses to make judgements, and the importance she

or he attaches to each of the cues.

For instance, Skanr et al (2000) studied the diagnostic

judgements of GPs, cardiologists, and medical students.

Through their modelling of how individuals used information to make a diagnosis, they highlighted the variation in the use of information cues. One-third of

participants used relative heart volume as the most

important cue as opposed to cardiac enlargement,

which was identified in the optimal strategy.

As well as being able to identify possible sources of error

in judgement which may affect judgement accuracy

the results of social judgement analysis studies can be

used to provide cognitive feedback to participants as a

way of improving their accuracy. Cognitive feedback is

different to outcome feedback, which provides participants with the outcome of each case, in that it contains

information about the optimal strategy (how information

is related to the patient state in the environment) and

the individuals own policy (how she or he uses the

information). With this knowledge they can identify disparities and be aware of how to improve their use of

information (Wigton, 1996). Various studies that used

cognitive feedback have shown it can improve diagnostic

accuracy and prognostic predictions (Wigton, 1996).

Social judgement analysis requires individuals to make

judgements as they normally would, and then uses statistical techniques to describe the relationship between

the information available to the judge and the judgement or decision made (Harries and Harries, 2001). The

focus of these studies is not the process of judgement,

rather an analysis of how information use is linked to

judgement accuracy, so in this way studies are able to

analyse in detail how and why judgements may differ

among individuals, as well as offering a way of improving accuracy through the use of cognitive feedback.

Another strength of social judgement analysis is that it

is not reliant on the ability of participants to self-report

their judgement processes, and can identify policies that

judges are unaware of (Harries and Harries, 2001).

However, social judgement analysis studies are often

reliant on the construction of scenarios, frequently with

limited sets of information presented in a way not found

in reality. So, as with all other types of study, they do

have limitations.

Conclusion

As highlighted by Hammond et al (1966) nursing judgements are complex, often involving the need to process

a large number of information cues. Key issues in the

study of such judgements are the analysis of judgement

accuracy and ways of improving accuracy.

More traditional approaches to the study of nursing

judgement have provided valuable insights into the

nature of expert nursing practice and the complexity of

practice. However, they have limitations in terms of

being able to provide the specific data needed to address

judgement accuracy.

Social judgement analysis approaches may be a way of

overcoming these limitations. However, as yet these

approaches have been more common in medicine,

examining the nature of medical diagnosis and prescribing (Skanr et al 2000; Harries et al 1996), than in nursing practice.

With nurses taking on roles requiring accurate judgement, it is time for clinicians and researchers to grapple

with this thorny issue in ways that will reveal possible

routes forward rather than offering just description.

NT 1 June 2004 Vol 100 No 22 www.nursingtimes.net

You might also like

- Small Volume Resuscitation in Hemorrhagic Shock: Historical and Scientific BackgroundDocument4 pagesSmall Volume Resuscitation in Hemorrhagic Shock: Historical and Scientific BackgroundYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Popo PopDocument1 pagePopo PopYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- WrhpofhppplplplplDocument1 pageWrhpofhppplplplplYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Llllo Pop Oppo Poo Popo PopDocument1 pageLlllo Pop Oppo Poo Popo PopYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Llllo Pop Oppo PoopDocument1 pageLlllo Pop Oppo PoopYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Cover, Editor, Daftar Isi JurnalDocument3 pagesCover, Editor, Daftar Isi JurnalYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- WrhpofhDocument1 pageWrhpofhYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Axs SaxasxDocument1 pageAxs SaxasxYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Universitas Sumatera UtaraDocument2 pagesUniversitas Sumatera UtaraYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Keti KanDocument5 pagesKeti KanYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument6 pagesAttachmentYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- PoppppppppppppppppppppppppDocument1 pagePoppppppppppppppppppppppppYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Abdominal MysteriesDocument15 pagesAbdominal MysteriesYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Medication Adherence InstrumentsDocument4 pagesMedication Adherence InstrumentsYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Penerapan Komunikasi Terapeutik Terhadap SikapDocument1 pagePengaruh Penerapan Komunikasi Terapeutik Terhadap SikapYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Uji Anova Program RDocument4 pagesUji Anova Program RYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Perlakuan Blok I II III Pupuk A 195 256 320 Pupuk B 200 287 310 Pupuk C 280 285 334 Pupuk D 198 233 315 Pupuk E 200 230 310 Pupuk F 218 245 300Document1 pagePerlakuan Blok I II III Pupuk A 195 256 320 Pupuk B 200 287 310 Pupuk C 280 285 334 Pupuk D 198 233 315 Pupuk E 200 230 310 Pupuk F 218 245 300Yosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Kajian Interaksi Obat CKDDocument7 pagesKajian Interaksi Obat CKDCinantya Meyta SariNo ratings yet

- Bill Lyons, MD Bill Lyons, MDDocument21 pagesBill Lyons, MD Bill Lyons, MDCharisse Nicole DiazNo ratings yet

- Antihypertensive Agents: Dosing Requirements in P Atients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument5 pagesAntihypertensive Agents: Dosing Requirements in P Atients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Mus Culo Skeletal Exam OutlineDocument14 pagesMus Culo Skeletal Exam OutlineYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Skenario Discharge PlaningDocument2 pagesSkenario Discharge PlaningYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Analisis Faktor-Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Motivasi Perawat DalamDocument1 pageAnalisis Faktor-Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Motivasi Perawat DalamYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Training Exercises & Presentations - Presentations - Discharge PlanningDocument15 pagesTraining Exercises & Presentations - Presentations - Discharge PlanningYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Multidimensional AspectsDocument14 pagesAnalysis of Multidimensional AspectsYosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- 7Document6 pages7Yosdim Si SulungNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Demo StatDocument5 pagesDemo StatCalventas Tualla Khaye JhayeNo ratings yet

- Building Social CapitalDocument17 pagesBuilding Social CapitalMuhammad RonyNo ratings yet

- HeavyReding ReportDocument96 pagesHeavyReding ReportshethNo ratings yet

- Instructional MediaDocument7 pagesInstructional MediaSakina MawardahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Coming of SpainDocument4 pagesChapter 6 Coming of SpainJayvee MacapagalNo ratings yet

- Keir 1-2Document3 pagesKeir 1-2Keir Joey Taleon CravajalNo ratings yet

- Neuralink DocumentationDocument25 pagesNeuralink DocumentationVAIDIK Kasoju100% (6)

- The Squeezing Potential of Rocks Around Tunnels Theory and PredictionDocument27 pagesThe Squeezing Potential of Rocks Around Tunnels Theory and PredictionprazNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument50 pagesPDFWalaa RaslanNo ratings yet

- Qsen CurriculumDocument5 pagesQsen Curriculumapi-280981631No ratings yet

- People Vs GonaDocument2 pagesPeople Vs GonaM Azeneth JJ100% (1)

- Schedule Risk AnalysisDocument14 pagesSchedule Risk AnalysisPatricio Alejandro Vargas FuenzalidaNo ratings yet

- Audi A4 Quattro 3.0 Liter 6-Cyl. 5V Fuel Injection & IgnitionDocument259 pagesAudi A4 Quattro 3.0 Liter 6-Cyl. 5V Fuel Injection & IgnitionNPNo ratings yet

- The Main Ideas in An Apology For PoetryDocument6 pagesThe Main Ideas in An Apology For PoetryShweta kashyap100% (3)

- Wallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy JournalDocument1 pageWallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy Journal胡知行No ratings yet

- Formulating A PICOT QuestionDocument4 pagesFormulating A PICOT QuestionKarl RobleNo ratings yet

- Security and Azure SQL Database White PaperDocument15 pagesSecurity and Azure SQL Database White PaperSteve SmithNo ratings yet

- 4 Transistor Miniature FM TransmitterDocument2 pages4 Transistor Miniature FM Transmitterrik206No ratings yet

- A User's Guide To Capitalism and Schizophrenia Deviations From Deleuze and GuattariDocument334 pagesA User's Guide To Capitalism and Schizophrenia Deviations From Deleuze and Guattariapi-3857490100% (6)

- Caucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusDocument8 pagesCaucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusSimonNo ratings yet

- Conspicuous Consumption-A Literature ReviewDocument15 pagesConspicuous Consumption-A Literature Reviewlieu_hyacinthNo ratings yet

- Emcee - Graduation DayDocument5 pagesEmcee - Graduation DayBharanisri VeerendiranNo ratings yet

- QUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaDocument43 pagesQUARTER 3, WEEK 9 ENGLISH Inkay - PeraltaPatrick EdrosoloNo ratings yet

- Rosa Chavez Rhetorical AnalysisDocument7 pagesRosa Chavez Rhetorical Analysisapi-264005728No ratings yet

- Physiotherapy For ChildrenDocument2 pagesPhysiotherapy For ChildrenCatalina LucaNo ratings yet

- Basilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Document1 pageBasilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Sealtiel1020No ratings yet

- mc96 97 01feb - PsDocument182 pagesmc96 97 01feb - PsMohammed Rizwan AliNo ratings yet

- 10 Proven GPAT Preparation Tips To Top PDFDocument7 pages10 Proven GPAT Preparation Tips To Top PDFALINo ratings yet

- Equilibrium of Firm Under Perfect Competition: Presented by Piyush Kumar 2010EEE023Document18 pagesEquilibrium of Firm Under Perfect Competition: Presented by Piyush Kumar 2010EEE023a0mittal7No ratings yet

- When Karl Met Lollo The Origins and Consequences of Karl Barths Relationship With Charlotte Von KirschbaumDocument19 pagesWhen Karl Met Lollo The Origins and Consequences of Karl Barths Relationship With Charlotte Von KirschbaumPsicoorientación FamiliarNo ratings yet