Professional Documents

Culture Documents

07 05 05

Uploaded by

BrianJakeDelRosarioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

07 05 05

Uploaded by

BrianJakeDelRosarioCopyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

Ethics in Social Networking: A Framework for Evaluating Online

Information Disclosure

Ludwig Christian Schaupp

West Virginia University

clschaupp@mail.wvu.edu

Lemuria D. Carter

Dietrich L. Schaupp

North Carolina A&T University

West Virginia University

ldcarte2@ncat.edu

dietrich.schaupp@mail.wvu.edu

Abstract

of their own social networks) for publication on the

website. This profile offers viewers an opportunity to

peruse user profiles, with the intention of contacting or

being contacted by others. These connections afford

users the opportunity to network with business

professionals, reconnect with old friends, find a new

job, etc.

In addition to the staggeringly high usage rates

among certain demographic groups, so, also are the

amount and type of information participants freely

reveal.

Category based representations of an

individuals broad interests are a uniform feature

across most networking sites [2]. These categories

include a persons hobbies, literary background,

political views, sexual preferences to name but a few.

In addition, personally identifiable information (such

as contact information) is often times provided and

intimate pictures of a persons private life and social

circle are often displayed as well [3].

Such apparent openness to reveal personal

information to vast networks of loosely defined

friends calls for a closer look at the ethical

implications of the decision at hand. IS researchers

have explored social networking in diverse contexts [48]. Specifically, [9] investigates issues of trust and

intimacy in online social networks, [10, 11] focus on

participants strategic representation of themselves to

others; and [2] discusses harvesting online social

network profiles to obtain recommendations. In this

study, we focus on the ethical decisions involved in

participating in a social networking site.

The

implications on an individuals privacy are undeniable

when discussing the posting of personal information

anywhere on the Internet let alone in an environment as

loose as a social networking site, but to date the ethics

of the decision to actively participate have not been

examined. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerburg was

recently quoted as saying that privacy was an

outdated social norm. In the virtual online

communities that are formed within these social

networking sites this appears to be true. Previous

research has demonstrated that online relationships

develop in social networking sites despite perceived

Participation and membership in social networking

sites has exploded in the past several years. Services

such as Myspace, Facebook, and LinkedIn have

evolved from niche communities to active societies. In

addition to an increase in usage rates among certain

demographic groups, there has also been an increase

in the amount and type of information participants

freely reveal. In this paper, we integrate decision

making research from marketing, theology and privacy

literature to explain information disclosure in online

communities. In particular, we use Potters Box to

propose a framework for evaluating the ethical

implications of online information disclosure.

Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: social networks, ethics, online

community

1. Introduction

Participation and membership in social networking

sites has exploded in the past several years. Services

such as Myspace, Facebook, and LinkedIn have

evolved from niche communities to active societies.

Facebook surpassed the 400 million worldwide users

milestones this past April [1]. Facebook CEO Mark

Zuckerburg commented on the significance of the 400

million user mark by explaining that if you are building

a website most of your users are probably Facebook

users too and if they are not they will be soon [1].

Zuckerburg went onto highlight how each new

Facebook service gets faster adoption rates amongst

users. Facebook Mobile hit the 100 million user mark

after three years and the most recently launched

Facebook Connect which hit the 100 million user

milestone in a mere fifteen months [1].

This rapid increase in participation has been

accompanied by a progressive diversification and

sophistication of purposes and usage patterns across

these sites. Most social networking websites have a

core set of features in common: an individual creates a

profile (a representation of their selves and often times

1530-1605/11 $26.00 2011 IEEE

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

trust and privacy safeguards being weak [12]. The

implications of which become magnified and are of

particular interest to both the private sector (marketers,

clients, investors) and the public (legislation of privacy

issues).

In this paper, we develop an ethical framework

used to evaluate the ethical decisions involved in

participating in a social networking site. We integrate

research from three diverse yet relevant fields marketing, ethics and privacy literature - to explain

individual user information disclosure on social

networking sites. In particular, we use Potters Box to

propose a framework for evaluating the ethical

implications of online information disclosure.

The remainder of this paper is organized as

follows. We first elaborate on social networks in

section 2. In section 3 we introduce and discuss an

ethical framework of social networking. Then we

discuss the implications of this framework on the

individual user in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the

implications of Potters Box on research and practice.

Finally, we summarize our findings and conclude in

section 6.

2. Theoretical development

While social networking sites share the basic purpose

of online interaction and communication, specific goals

and patterns of usage vary significantly across social

network sites. The most common model is based on

the presentation of the participants profile and the

visualization of his or her network of relations to others

such is the case with Facebook. For the purposes of

this study, we define [13] a social networking site as a

web based service that allow individuals to (1)

construct a public or semi-public profile within a

bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with

whom they share a connection, and (3) view and

traverse their list of connections and those made by

others within the system.

What makes social network sites unique is not that

they allow individuals to meet strangers, but rather that

they enable users to articulate and share their social

networks. This can result in connections between

individuals that would not otherwise be made, but that

is often not the goal, and these meetings are frequently

between "latent ties" [14] who share some offline

connection. On many of the large social networking

sites (SNSs), participants are not necessarily

"networking" or looking to meet new people; instead,

they are primarily communicating with people who are

already a part of their extended social network. Online

social networking sites can therefore morph into a

variety of things including online classifieds at one end

of the spectrum and blogging at the other.

First, a users anonymity varies from site to site.

In popular sites such as Facebook the use of real names

to represent account profiles to the rest of the online

community may be encouraged. Or the use of real

names and contact information could be openly

discouraged as in the dating website Match.com, that

attempts to shield the personal identity of its users by

making the linkage to their online persona more

difficult [3].

Regardless of the approach to

identifiability, most sites encourage the publication of

personal photos.

In addition, the type of information revealed or

elicited often centers around hobbies and interests;

however, it is extremely common for users to post

information that is intended to be semi-public

information such as past and current schools and

employment; private information such as drinking,

drugs, and sexual preferences and orientation; and

open-ended entries [3].

Also, visibility of information is highly variable.

On certain types of sites (i.e. dating sites) any member

may view any other members profile. On sites such as

Facebook (no pseudonyms required) access to personal

information is limited to friends that are part of the

direct or indirect network of friends belonging to the

profile owner [3].

Given all of this, anecdotal evidence suggests that

participants are willing and happy to disclose as much

information as possible to as many people as possible.

This study presents a framework that can be used to

evaluate information disclosure in online communities.

2.1 Online community

Online communities are conceived as continuous

communication relationships that are computer

mediated [15]. To date, IS researchers have studied

communities of practice (CoPs) extensively in an effort

to better facilitate the creation and dissemination of

knowledge within organizations [16-18].

Online

communities have similar characteristics as CoPs.

Like CoPs, they are collaborative which help to

develop shared understandings and facilitate

relevant knowledge building [17]. However, unlike

CoPs, online communities are not affiliated with a firm

and have the potential to be accessible to a larger user

base [19]. Online communities are also less amenable

to organizational control because members of the

community are not affiliated with a single

organization, often times being comprised of members

with absolutely no affiliation or knowledge of each

other outside of the community. Wellman and Gullia

[20] described the online community as a relational

community, concerned with social interaction among

its members.

These are interest-organized

communities, such as hobby clubs or spiritual groups,

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

facilitating virtual collaboration among community

members with the potential of transforming the

activities of off-line into an online context [21, 22].

Prior CoP literature has identified these

communities as having two key functions: (1) the

creation and dissemination of knowledge and (2) the

socialization and development of social identity of

members [17, 23-25]. Prior research has shown that the

social interaction supported by technology is crucial to

the success of online communities [26-28].

Additionally, human-computer interaction (HCI)

research has shown that website attributes (e.g.

usefulness and ease of use) influence member

participation in online communities [29, 30].

Regardless of the perspective taken, researchers agree

that online communities can be made feasible by the

presence of groups of people who interact with specific

purposes, under the governance of certain policies, and

with the facilitation of computer mediated

communication [31].

2.2 Social network theory and ethics

The relation between personal ethics and persons

social network is multi-faceted. In certain scenarios

we want information about ourselves to be known only

by a small circle of friends. In other scenarios, we are

more comfortable sharing information about ourselves

to unknown strangers, but not to our family and

friends.

Social network theorists have discussed the

relevance of relations of different depth and strength in

a persons social network [4, 5] and the importance of

weak ties in the flow of information across different

nodes in a network. Network theory has also been

used to explore how distant nodes can get

interconnected through relatively few random ties [68].

While privacy is likely at risk in social networks,

information is willingly provided by users. As a result,

whether or not to post information comes down to an

ethical decision made by the individual user whether or

not the material is to be published on the site.

3. Ethical framework for decision-making

One aspect about moral reasoning is that it is often

times a topic for discussion, but seldom one that is ever

the basis of action. The authors suspect that individual

social network users accept that privacy may be at risk

and are fearful that any ethical issue could potentially

cause embarrassment. However, users provide

information willingly. There are several factors that

drive individuals decisions on social networking sites:

such as signaling [11] because the perceived benefit of

selectively revealing data to strangers may appear

larger than the perceived costs of possible privacy

invasions; peer pressure and herding behavior; relaxed

attitudes towards (or lack of interest in) personal

privacy; incomplete information about the risks of

privacy loss and the implications of such); faith in the

networking service or trust in its members. In the

following paragraphs we present an ethical framework

for decision making scenarios on social networking

sites and the implications of such.

What then is required to construct a defensible ethical

decision? Moral justification is possible when a

pattern of moral deliberation is outlined and where

considerations are outlined and given appropriate

weight. In essence, it is a systematic way of looking at

ethical analysis that provides a guideline for action.

Dr. Ralph Potter of the Harvard Divinity School

has developed a model of moral reasoning that sizes up

the circumstances, asks what values instigated the

decision, what ethical principle is feasible, and what

social groups are the recipients of ones loyalty. This

is of particular interest in a social networking context

because our social boundaries are blurred between

close intimate friends and friends that are friends

of your friends and then friends of their friends.

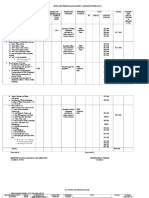

The Potter Box [32] is an ethical decision making

framework utilizing four categories which Potter

identifies as universal to all ethical dilemmas.

Definitions

Loyalties

Values

Principles

Figure 1. Potters Box

In implementing this model, the decision maker is

asked to discern the values that instigated the decision,

the feasible ethical principles, and the social group that

is the recipient of ones loyalty. The process allows an

individual to systematically analyze the potential

outcomes of a particular decision by giving careful

consideration to the issues of loyalty and long-term

relationships. As the model shows, the first quadrant

forces the participant to define the circumstance; the

second examines the values surrounding the

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

circumstance. The third quadrant appeals to an ethical

principle, and the fourth examines the clarity of ones

loyalties [33].

Potters Box serves as a decision making tool in

social ethics combining the need for an appeal for an

explicit moral principle with the need for addressing

the sociological values of the culture and the

assignment of loyalties to a specific individual or

group. It combines these elements to generate a

conclusion that is morally justified. This is done by

using the box as a cycle and asking relevant questions

in each quadrant. The cycle is initiated when one first

focuses on the ethical principles and is culminated by

examining the question of loyalties. Each stage of the

cycle defines and clarifies the process and the

elemental relationship of each quadrant to the others.

The process requires several interactions for a morally

justified conclusion [33].

This process was extended [34] by refining

Potters original model to highlight the main elements

involved in making an ethical decision. Strassens

model not only expands on the underlying reasons to

which ethical decisions are subject but depicts the

possible interaction between the four quadrants [34].

For the purposes of this study the model has been

refined to highlight the ethical decision making process

in social network participation. This model not only

expands on the underlying reasons to which ethical

decisions are subject but depicts the possible

interaction between the various quadrants. According

to this model, ethical decisions are affected by four

dimensions:

1) The empirical definition of the situation,

which includes various situation specific

variables (such as perceived risk and

legitimacy of various alternative courses of

action) that might affect the individuals

perception of the situation at hand (i.e. posting

an incriminating picture of ones self).

2) The moral reasoning dimension, which

includes the three major normative theories of

ethics: rule-deontological, act-deontological,

and teleological. It also adds the theory of

divine command, where principles are

justified because they are god given [35].

3) The theological dimension, for which one

explanation is that an ethical thought requires

some answer to the existential question, Why

ought I be moral?

4) The loyalties dimension, which focuses on the

groups that might influence the individuals

ethical perceptions.

The extended model adapted for the purposes of

this study (see Figure 2), like Potters Box,

provides a means to further illustrate the

constructs underlying the ethical decision making

process. The adapted model used in this study

provides a framework for justifying an ethical

decision regarding an individuals information

revelation in a social networking context. This

model also addresses the salient elements in

reasoning though social network moral decisions,

so that the discussion can move beyond situation

specific ethics to why an individual makes a

particular decision given the outcomes being

sought [33].

The models also demonstrate how two

individuals may arrive at opposite or conflicting

conclusions yet have ethically defensible

decisions. By illustrating these different yet

defensible positions, the models allow the

participants to recognize the factors that made

their particular decision the correct one.

- - - - - - - - - - - Feedback- - - - - - ----------- -------

Facts

Particular Judgment

Empirical Definition of

Situation

Mode of Moral Reasoning

a)

a)

b)

c)

d)

Threat

Authority

Social Change

Scientific

Integrity

b)

c)

d)

Center of Values or

Loyalties

a)

b)

c)

d)

Means

Personal

Group

Ultimate

revelational

(divine command)

Regular (ruledeontoloigcal

Situational (actdeontological)

Teleological

Ground of Meaning or

Theology

a)

b)

c)

d)

Human nature

Love, justice, and

realism

Justification and

sanctification

Mission

Figure 2. Elements Involved in Justifying an Ethical

Social Networking Decision ---Adapted from Potter

[32] and Strassen [34]

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

4. Ethical framework and the social network user

The following subsections highlight the complexity of

the ethical decision at hand. Below each quadrant of

the social network ethical framework is explained in

more thorough detail.

4.1 Empirical definition of the situation

The ethical decision at hand in most social networking

revelation situation is influenced from a variety of

sources. The first element that must be considered by

the individual social network user is what threats they

may be exposing themselves to by posting the personal

information in question. Secondly, a consideration has

to be made towards the issue of perceived risk and

alternative courses of action. The authority in a

specific scenario is often times multi-faceted in that

certain information revelation actions are intended for

different friends within the individual users social

network. For example, offline social networks are

made up of personal ties that can only be loosely

categorized as weak or strong, but in reality are

extremely diverse in terms of how close and intimate a

subject perceives a relation to be. On the contrary,

online social networks often overly simplify these

intricate connections into a simplistic binary

relationship: friend or not. This limits an individual

users ability to change or mask their value system

online because everything that is posted is available for

all friends to see, regardless of how strong or weak

the tie.

4.2 Mode of moral reasoning

In theology, Divine Command approaches to ethics

tend also to be deontological in approach. Something is

moral because God commands it and something is

immoral because God forbids it [36].

Deontological forms of moral reasoning focus on

whether a particular moral action is intrinsically right

or wrong and usually right and wrong are

deontological categories. This is multi-faceted issue in

the sense that right and wrong will vary dependent

upon the friend. The most famous Western

philosophical version of this is German Enlightenment

philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Kant argued

that actions were either right or wrong regardless of

consequences. He argued that one could deduce

unbreakable moral rules from a universal categorical

imperative [36]. First, to be moral, an action must be

universalizable, i.e., one must be willing that everyone

should do it. Second, an action is moral if it never

treats persons merely as means to an end, but always

treats persons as ends in themselves [36].

By contrast, teleogical approaches to ethics place

more emphasis on goals or outcomes. Presently, the

most predominant version of teleological ethics is

utilitarianism. An action is Good (good and bad

are teological terms as right and wrong are

deontological terms) if it leads to the most happiness

for the most people with the least unhappiness for the

least people. Utilitarianism is associated with the

British lawyer Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and his

disciple, the civil libertarian John Stuart Mill (18061873) [36].

4.3 Center of values or loyalties

Friend takes on a variety of definitions, some users

are willing to accept anyone as a friend while other

users stick to a more conservative definition [10].

However, in most instances users tend to list anyone as

friend that they do not actively dislike [10].

Ultimately, this means that people are indicated as

Friends even though the user does not particularly

know or trust the person [10].

From the group standpoint, Donath and Boyd [11]

explain that while the number of strong ties that a

person may maintain on a social networking site may

not be significantly increased by these online

communities; however, the number of weak ties one

can form and maintain may be able to increase

substantially because the technology is well suited to

facilitate this type of communication with these weak

ties. An online social network ultimately can list

hundreds of direct friends and literally hundreds of

thousands of additional within three degrees of

separation [11, 37].

Ultimately, this implies online social networks are

both larger, vaster, and have much weaker ties as

compared to offline social networks. In other words,

thousands of users may be classified as friends of

friends of an individual and become able to access their

personal information, while, at the same time, the

threshold to qualify as friend on somebodys network

is low [3]. Therefore, decision at hand is more

complex in nature from the standpoint that the

revelation of information on an online social network

is exposed for all to see.

4.4 Ground of meaning or theology

Why should I be moral? This is the underlying factor

which many social network users face in their decision

to post private information. On a higher level, what is

moral and what is not? It comes down to a variety of

factors that will be individual specific. It is human

nature to act in ones best interest; however, ones best

interest is variable on a case by case basis. It is the

process of justifying ones actions that enables them to

formalize their decision to reveal personal information

about themselves.

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

5. Discussion

This study integrates research from three diverse fields

to explain information disclosure in online

communities. According to Potters Box there are four

dimensions that effect ethical decision making. We

posit that these dimensions are applicable to social

networking and the implications of which should be of

keen interest to both the private and public sectors. The

box serves as a guideline moving from one box to the

next. The modified Potters Box adapted for a social

networking context serves as an exercise in social

ethics. It combines the need for an appeal for an

explicit moral principle with the need for addressing

the sociological values of the culture and the

assignment of our loyalties to a specific individual or

group in order to generate a conclusion that is morally

defensible (justified). This is done by using the box as

a cycle. First, by asking the relevant questions in each

quadrant; then expanding it as a circle whereby you

focus on the ethical principle, and finally examine the

question of loyalties. Each cycle redefines and

clarifies the process and the elemental relationship of

each quadrant to the others. It is a process that requires

several iterations for a morally justified conclusion.

The moral justification ultimately relies on the

explicit moral principle selected. Although, often

articulated, the need for alternatives available for moral

justification (principles) in ethical decision-making on

information disclosure is often a befuddlement for the

social network user. Most often times only considering

the ethical decision and privacy implications that result

only for a second or not at all. The proposed

framework represents an initial attempt to present a

comprehensive view of ethical information disclosure

in social networking. It can serve as a foundation for

future studies on online information sharing in this

digital age.

6. Future research

The proposed framework presents numerous fruitful

avenues for future research. Future studies should

conduct a qualitative assessment to explore the

intricacies of ethical decision making in this context.

Following the qualitative assessment, quantitative

studies should be used to develop and assess a

replicable research model. The model could be tested

in various online contexts such as online dating and

professional networking.

Given the impact of

demographics on social network website utilization,

future research should explore the impact factors such

as age, gender, scope of network, and ethnicity on

ethical information disclosures within online

communities.

7. Conclusion

Online social networks form virtual communities

(online communities) for which users register and

identify with connecting them to not only their direct

friends, but also their indirect friends. Information

revelation onto the site and thus into the community

allows provides both friends and extended friends the

opportunity to view private, potentially sensitive

information. This framework serves as a foundation

for future research into the ethical decision making

process of social network users.

7. References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

Ha, A. (2010) Facebook has 400M users, 100M on

Connect. VentureBeat Volume,

Liu, H. and P. Maes. Interestmap: Harvesting

social network profiles for recommendations. in

Beyond Personalization - IUI 2005. 2005. San

Diego, California.

Gross, R. and A. Acquisti. Information Revelation

and Privacy in Online Social Networks. in

Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society.

2005. Alexandria, VA.

Granovetter, M., The strength of weak ties.

American Journal of Sociology, 1973. 78: p. 1360

1380.

Granovetter, M., The strength of weak ties: A

network theory revisited. Sociological Theory,

1983. 1: p. 201233.

Milgram, S., The small world problem. Psychology

Today, 1967. 6: p. 6267.

Milgram, S., The familiar stranger: An aspect of

urban anonymity, in The Individual in a Social

World: Essays and Experiments, J.S. S. Milgram,

and M. Silver, Editor. 1977, Addison-Wesley:

Reading, MA.

Watts, D., Six Degrees: The Science of a

Connected Age. 2003: W.W.Norton & Company.

Boyd, D. Reflections on friendster, trust and

intimacy. in Intimate (Ubiquitous) Computing

Workshop - Ubicomp 2003. 2003. Seattle,

Washington.

Boyd, D. Friendster and publicly articulated social

networking. in Conference on Human Factors and

Computing Systems (CHI 2004). 2004. Vienna,

Austria.

Donath, J. and D. Boyd, Public displays of

connection. BT Tlchnology Journa;, 2004. 22: p.

7182.

Dwyer, C., S.R. Hiltz, and K. Passerini. Trust and

Privacy concern within social networking sites: A

comparison of Facebook and Myspace. in

Americas Conference on Information Systems.

2007. Keystone, Colorado.

Boyd, D.M. and N.B. Ellison, Social Networking

Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal

of Computer Mediated Communication, 2007.

13(1).

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

Haythornthwaite, C., Social networks and Internet

connectivity effects. Information, Communication,

& Society, 2005. 8(2): p. 125-147.

Fuchs, C., Toward a Dynamic Theory of Virtual

Communities International Journal of Knowledge

and Learning, 2008. 3(4-5): p. 372-403.

Brown, J.S. and P. Duguid, The Social Life of

Information. 2002, Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

Hara, N., Communities of Practice: Fostering

Peer-to-Peer Learning and Informal Knowledge

Sharing in the Workplace. 2009, Berlin: Springer.

Wasko, M.M. and S. Faraj, Why Should I Share?

Examining Social Capital and Knowledge

Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice.

MIS Quarterly, 2005. 29(1): p. 35-57.

Dahlander, L. and M.G. Magnusson, Relationships

between Open Source Software companies and

communities: Observations from Nordic firms.

Research Policy, 2005. 34: p. 481-493.

Wellman, B. and M. Gullia, Net Surfers Don't Ride

Alone: Virtual Communities as Communities 1995,

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Massey, A.P., M.M. Montoya-Weiss, and Y.T.

Hung, Because time matters: temporal

coordination in global virtual project teams.

Journal of Management Information Systems,

2003. 19: p. 129 156.

Wenger, E. and W.M. Snyder, Communities of

Practice: The Organizational Frontier Harvard

Business Review, 2000. 78: p. 139-145.

Brown, J.S. and P. Duguid, Organizational

Learning and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a

Unified View of Working, Learning, and

Innovation. Organization Science, 1991. 2(1): p.

40-57.

Ryu, C., et al., Knowledge Acquisition Via Three

Learning Processes in Enterprise Information

Portals: Learning by Investment, Learning by

Doing, and Learning from Others. MIS Quarterly,

2005. 29(2): p. 245-278.

Wenger, E., R. McDermott, and W.M. Snyder,

Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to

Managing Knowledge 2002, Boston: Harvard

Business School Press.

Garretty, K., P.L. Robertson, and R. Badham,

Integrating communities of practices in technology

development projects. International Journal of

Project Management, , 2004. 22: p. 351 358.

Preece, J., Online Communities: Designing

Usability, Supporting Sociability. 2000, Chichester,

England: John Wiley & Sons.

Wang, Y., Q. Yu, and D.R. Fesenmaier, Defining

the virtual tourist community: implications for

tourism marketing. Tourism Management, 2002.

23: p. 407 417.

Kuo, Y.F., A study on service quality of virtual

community websites. Total Quality Management,

2003. 14: p. 461 473.

Preece, J., Sociability and usability in online

communities: Determining and measuring success.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

Behavior and Information Technology Journal,

2001. 20(5): p. 347-356.

Lin, H.F. and G.G. Lee, Determinants of success

for online communities: An empirical study.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 2006. 25(6):

p. 479-488.

Potter, R.B., The Logic of Moral Argument, in

Toward a Discipline of Social Ethics, P. Deats,

Editor. 1972, Boston University Press: Boston,

MA.

Schaupp, D.L., T.G. Ponzurick, and F.W. Schaupp,

The Right Choice: A Case Method for Teaching

Ethics in Marketing. Journal of Marketing

Education, 1992. 14(1): p. 1-11.

Stassen, G., A Social Theory Model for Religous

Social Ethics. Journal of Religous Ethics, 1977.

5(1): p. 9-37.

Vitell, S.J., Marketing Ethics: Conceptual and

Empirical Foundations of a Positive Theory of

Decision Making in Marketing Situations Having

Ethical Content. 1986, Texas Tech University.

Westmoreland-White, M.L. Styles of Moral

Reasoning/Modes of Moral Discourse. Faith &

Social Justice: In the spirit of Richard Overton and

the 17th C. Levellers 2009 April 26 [cited June 14,

2010].

Strahilevitz, L.J., A social networks theory of

privacy. 2004, The Law School, University of

Chicago.

You might also like

- Sample Endorsement LetterDocument1 pageSample Endorsement LetterBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- 02 85 Medical Management of A MiscarriageDocument16 pages02 85 Medical Management of A MiscarriageBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- HallelujahDocument1 pageHallelujahVeronika ZunhammerNo ratings yet

- Graduation PrayerDocument1 pageGraduation PrayerBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- 2016 WFP FidsfdsnalDocument72 pages2016 WFP FidsfdsnalBrianJakeDelRosario0% (1)

- Release Crash InfoDocument1 pageRelease Crash InfoBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Graduation PrayerDocument1 pageGraduation PrayerBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Graduation PrayerDocument1 pageGraduation PrayerBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- ArtistDocument2 pagesArtistBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Epic of Gilgamesh Shijing Vedas Gathas Iliad Odyssey PoeticsDocument2 pagesEpic of Gilgamesh Shijing Vedas Gathas Iliad Odyssey PoeticsBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Saln Form BlankdDocument2 pagesSaln Form BlankdBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Graduation PrayerDocument1 pageGraduation PrayerBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Release Crash InfoDocument1 pageRelease Crash InfoBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Prenatal InformationDocument5 pagesPrenatal InformationBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Exam 5Document1 pageExam 5BrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- History of Yahoo Yahoo! Was Started at Stanford University. It Was Founded in January 1994 by Jerry Yang andDocument3 pagesHistory of Yahoo Yahoo! Was Started at Stanford University. It Was Founded in January 1994 by Jerry Yang andBrianJakeDelRosario100% (1)

- Saln Form BlankdDocument2 pagesSaln Form BlankdBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Sample Endorsement LetterDocument1 pageSample Endorsement LetterBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Saln 2012 FormDocument3 pagesSaln 2012 FormBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Saln Form BlankdDocument2 pagesSaln Form BlankdBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Saln Form BlankdDocument2 pagesSaln Form BlankdBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- HarkDocument1 pageHarkBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Skill LevelsDocument2 pagesReading Comprehension Skill LevelsBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Letter of Appeal ExampleDocument2 pagesLetter of Appeal ExampleBrianJakeDelRosario100% (1)

- Noli Me Tangere Chapter 8 SummaryDocument1 pageNoli Me Tangere Chapter 8 SummaryBrianJakeDelRosario100% (1)

- Example of RiddlesDocument5 pagesExample of RiddlesBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Bado DangwaDocument2 pagesBado DangwaBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Trivia About Biology: Ma'Am Ma Teresa LagangDocument3 pagesTrivia About Biology: Ma'Am Ma Teresa LagangBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Tongue TwisterDocument1 pageTongue TwisterBrianJakeDelRosarioNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-284997804100% (1)

- l1 - Worksheet Apps and Social MediaDocument5 pagesl1 - Worksheet Apps and Social Mediarakgonz100% (2)

- Effects of Social Media On Student's Mental HealthDocument17 pagesEffects of Social Media On Student's Mental HealthSaief AhmedNo ratings yet

- Module-4-Group 1Document33 pagesModule-4-Group 1May AndayaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-437205356No ratings yet

- Cooperative Learning With Harnessing Social Network Site Facebook For Speaking Course in Blended Learning Environment-RevisiDocument11 pagesCooperative Learning With Harnessing Social Network Site Facebook For Speaking Course in Blended Learning Environment-RevisiJAMRIDAFRIZALNo ratings yet

- 21 STDocument6 pages21 STDENNIS RAMIREZNo ratings yet

- Social Media Guidelines For VolunteersDocument2 pagesSocial Media Guidelines For Volunteersmartha.isNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Social Media Marketing 0132551799Document32 pagesTest Bank For Social Media Marketing 0132551799JoeBrooksqekd100% (37)

- Array: Aristea Kontogianni, Efthimios AlepisDocument12 pagesArray: Aristea Kontogianni, Efthimios AlepisSehaj PreetNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Project On Social MediaDocument85 pagesSummer Training Project On Social MediaRohitRadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Internet, Social Media AddictionDocument10 pagesA Case Study of Internet, Social Media AddictionJeordan LimbagaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media On Mental Health of Students: AbstractDocument6 pagesImpact of Social Media On Mental Health of Students: AbstractAN G EL0% (1)

- The Social Media Debate Unpacking The Social, Psychological, and Cultural Effects of Social MediaDocument249 pagesThe Social Media Debate Unpacking The Social, Psychological, and Cultural Effects of Social MediaRockNo ratings yet

- Internet Dating Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesInternet Dating Thesis Statementgbvjc1wy100% (2)

- Discovering The Self - The Digital SelfDocument27 pagesDiscovering The Self - The Digital SelfKen Ken CuteNo ratings yet

- A Study On Positive and Negative Effects of Social Media On SocietyDocument8 pagesA Study On Positive and Negative Effects of Social Media On SocietyAleksandr BinamNo ratings yet

- The Right To Privacy and Identity On Social Network Sites by Milton Themba Skosana (LLM, UNISA)Document226 pagesThe Right To Privacy and Identity On Social Network Sites by Milton Themba Skosana (LLM, UNISA)Nnana Zacharia MatjilaNo ratings yet

- CU2 RebornDocument18 pagesCU2 RebornRudolf Den HartoghNo ratings yet

- English Q2, Week5, Day1 - Selection - Social MediaDocument1 pageEnglish Q2, Week5, Day1 - Selection - Social MediaNova Penera EscobarNo ratings yet

- BBSS Paintball TournamentDocument70 pagesBBSS Paintball TournamentAkmal Hanis JefriNo ratings yet

- Advanced Photoshop Issue 043 PDFDocument81 pagesAdvanced Photoshop Issue 043 PDFDipesh BardoliaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media On Administrative Staff Employees in Case of Woldia UniversityDocument6 pagesImpact of Social Media On Administrative Staff Employees in Case of Woldia UniversityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media-09032023-5Document8 pagesImpact of Social Media-09032023-5uciffjjfffjNo ratings yet

- Students at Domalandan Center Integrated School I. Introduction and RationaleDocument3 pagesStudents at Domalandan Center Integrated School I. Introduction and RationaleNors CruzNo ratings yet

- MyNoteTakingNerd Best of The Best ReportDocument82 pagesMyNoteTakingNerd Best of The Best Reportmynotetakingnerd100% (12)

- Effects of Social Media On Business GrowthDocument17 pagesEffects of Social Media On Business GrowthAbdullahi100% (1)

- Using Social Network For Learning ENglishDocument5 pagesUsing Social Network For Learning ENglishThiện Trần0% (1)

- The Challenges of Social Media Research in Online Learning EnvironmentsDocument4 pagesThe Challenges of Social Media Research in Online Learning EnvironmentsIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet