RISK &

CAUSATION

FRANCES AVILES

MD MPH BSC

�COHORT STUDY

Cohort: group of people who share a common

characteristic

Identifies people with risk factors and

compares disease incidence to incidence rate in

another group of people without those risk

factors.

Connects Incidence to a Causality

Large Sample Sizes

Expensive/Time Consuming

�COHORT STUDY: RISK FACTOR

EXPOSURE

PROSPECTIVE: Towards the future; follows disease

incidence (MC)

RETROSPECTIVE: Looks into past archived data

Prospective studies follow a cohort into the future

for a health outcome.

Retrospective studies trace the cohort back in

time for exposure information after the outcome

has occurred. Retrospective studies group

subjects based on their exposure status and

compare their incidence of disease.

�Prospective Cohort

In a Hospital A group of heavy smokers and a

group of non-smokers are selected for a cohort

study. Lung Cancer incidence is assessed for the

following 5 years.

�Retrospective Cohort

�Start

?

Exposur

e

Time

Disease

�Cohort Study

outcome is measured after exposure

yields true incidence rates and relative risks

may uncover unanticipated associations with outcome

best for common outcomes

expensive

requires large numbers

takes a long time to complete

prone to attrition bias (compensate by using persontime methods)

prone to the bias of change in methods over time

�CASE CONTROL STUDY:

DISEASE

Uses a group of people with disease and a

matching group of non-diseased people

(CONTROL)

RETROSPECTIVE: Looks back in time for the

presence or absence of risk factors.

Looks for causality of risk factors by analyzing

the presence of risk factors in patients with given

disease and the absence of these RFs in the

selected patients that are not diseased.

�CASE CONTROL

In a hospital- A group of pts with LUNG CANCER is

selected along with a group without LUNG

CANCER. Smoking habits are assessed for each

group.

�Start

?

Disease

LOOK

BACK

Exposur

e

�Case Control

outcome is measured before exposure

controls are selected on the basis of not having

the outcome

good for rare outcomes

relatively inexpensive

smaller numbers required

quicker to complete

prone to selection bias

prone to recall/retrospective bias

�Risk

& Measurements

of Risk and Effect

�RISK

To analyze a Study, Risk needs to be assessed

Risk: the proportion of persons who are unaffected

at the beginning of a study period, but who could

possibly experience an event (e.g., death, disease,

or injury) during the study period

Quantifying Risk: Relative risk, attributable risk,

and the odds (or odds risk) ratio are measures

used to quantify risk in population studies

�The knowledge that something is a risk factor

for a disease can be used to help:

Prevent the disease.

Predict its future incidence and prevalence.

Diagnose it (diagnostic suspicions are higher if it is

known that a patient was exposed to the risk factor).

Establish the cause of a disease of unknown

etiology.

�Absolute Risk

The fundamental measure of risk is

incidence. The incidence of a disease is, in

fact, the absolute risk of contracting it.

If the INCIDENCE of disease is 10 per 10,000 people per Yr.

Then the ABSOLUTE RISK of a person actually contracting it

is also 10 per 1,000 per Yr., or 1% per Yr.

�Measures of RISK & EFFECT

Measures of effect to being exposed to a risk factor on the

risk of contracting a disease.

A number of different comparisons of risk can be made,

including relative risk, attributable risk, and the odds

ratio.

�Relative risk (RR)

How

many times exposure to the risk

factor increases the risk of contracting

the disease.

It is therefore the ratio of the incidence of the disease among

exposed persons to the incidence of the disease among

unexposed person

Because relative risk is a ratio of risks, it is sometimes called

the risk ratio, or morbidity ratio. In the case of outcomes

involving death, rather than just disease, it may also be called

the mortality ratio.

�Relative Risk (RR)

RELATIVE RISK : is the group more or less likely to develop

DZ?

[RR= INCIDENCE IN EXPOSED/INCIDENCE IN

UNEXPOSED]

For example, the incidence rate of lung cancer among smokers in

New Jersey is 20/1000, while the incidence rate of lung cancer

among nonsmokers in New Jersey is 2/1000.

Therefore, the chance of getting lung cancer (the relative risk) for this

New Jersey population is ?

�RELATIVE RISK REDUCTION

The proportion of risk reduction attributable to the intervention as

compared to a control.

RRR= 1 - relative risk

RRR= AR/IH

IH= highest incident rate

IL= lowest incident rate

Reports of risk reductions due to treatments in many clinical trials, and in

almost all pharmaceutical advertisements, are of relative risk reductions

There were 73 deaths from cardiovascular causes in the placebo

group (3293 men); the cardiovascular mortality rate was

therefore 73/3,293 = 0.022 (2.2%) in this group.

In the pravastatin group (3,302 men), there were 50

cardiovascular deaths, giving a mortality rate of 50/3,302 =

0.015, or 1.5%.

The RR of death in those given the drug is 1.5/2.2 = 0.68,

The RRR is (1 - 0.68)=0.32, or 32% showing that an impressive

32% of cardiovascular deaths were prevented by the drug.

The ARR is (2.2% - 1.5%) = 0.7% a far less impressivesounding figure, showing that of all men given the drug for 4.9

years, 0.7% of them were saved from a cardiovascular death.

�ATTRIBUTABLE RISK (AR)

The additional incidence of a disease that is attributable to the risk

factor in question. The difference in risk between exposed and

unexposed groups, or the proportion of disease occurrences that are

attributable to the Exposure

ATTRIBUTABLE RISK: how many more cases?

[AR= INCIDENCE RATE IN EXPOSED-INCIDENCE RATE IN UNEXPOSED]

Then, the risk of lung cancer attributable to smoking (the attributable risk) in this New

Jersey population is 20/1000 minus 2/1000 or 18/1000.

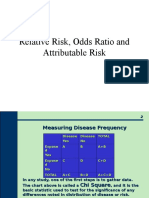

�2X2 Table

RISK EXPOSURE

UNEXPOSED

DZ

NO DZ

TOTAL

a+b

c+d

How many were exposed

How many were not exposed

How many How many do not

have disease

have disease

*Incidence in Exposed: a/a+b

*Incidence in Unexposed: c/c+d

Attributable Risk and Relative Risk are mainly

used for Cohorts Studies

Odds Ratio are commonly used for Case Control

Studies

�Attributable Risk Reduction

The difference in risk attributable to the

intervention as compared to control

Risk of intervention group Risk of Control Group

�Absolute Difference of Risk

Risk difference is the risk in the exposed group

minus the risk in the unexposed group.

If an exposure is harmful (as in the case of

cigarette smoking), the risk difference is

expected to be greater than 0.

If an exposure is protective (as in the case of a

vaccine), the risk difference is expected to be

less than 0.

Risk difference is also known as attributable risk.

Rate difference (absolute difference in rate) is

the rate in the exposed group minus the rate in

�ATTRIBUTABLE RISK PERCENT

Percent of cases due to exposure

Used to assess proportion of cases

due to risk factor.

AR%= RR-1/RR

�NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: NNT

NUMBER NEEDED TO HARM: NNH

PREVENTION: NNT

CAUSALITY: NNH

How many have to do something to prevent one

case of disease

How many would have to stop smoking? - NNT

How many pts would have to smoke? - NNH

�Number needed to Treat

Number of patients who need to be treated for 1

patient to benefit.

NNT=1/ARR.

�Number needed to Harm

Number of patients who need to be exposed to a

risk factor for 1 patient to be harmed.

NNH=1/AR

�ODDS RATIO

ODDS RATIO: Estimates the increased odds of having

risk factors when comparing disease and non-diseased

groups

[OR=ad/bc]

Not a prediction of disease

Estimates the

strength of risk factors.

Since incidence data are not available in a case-control study, the odds ratio can be

used as an estimate of relative risk when a disease is uncommon

� Of 200 patients in the hospital, 50 have lung cancer. Of

these 50 patients, 45 are smokers.

Of the remaining 150 hospitalized patients who do not

have lung cancer, 60 are smokers.

Use this information to calculate the odds ratio for

smoking and the risk of lung cancer.

People with lung cancer A = 45 B = 5

People without lung cancer C = 60 D = 90

(A)(D) (45)(90) / (B)(C) (5)(60)

4050/300= OR=13.5

An odds ratio of 13.5 means that the risk of lung cancer is

13.5 times higher in peoplewho smoke than in those who

do not smoke.

�CAUSATION

�CONCEPT OF CAUSE

An understanding of the causes of disease is

important in the health field not only for

prevention but also in diagnosis and the

application of treatment.

A cause of a disease is an event, condition,

characteristic, or combination of these factors

which plays an important role in producing the

disease.

A cause could be sufficient or necessary

�SUFFICIENT CAUSE

A cause is termed sufficient when it

inevitably/certainly produces or initiates a disease.

It is not usually a single factor, but often comprises

several components. e.g. cigarette smoking is one

component of the sufficient cause in lung cancer.

In general, it is not necessary to identify all the

components of a sufficient cause before effective

prevention can take place, since the removal of

one component may interfere with the action of

the others and thus prevent the disease.

�NECESSARY CAUSE

A cause is termed necessary if a disease

cannot develop in its absence.

Each sufficient cause has a necessary cause

as a component.

�Types of Causes

Sufficient - If the cause is present, disease will

always occur.

Necessary - The cause must be present for the

disease/condition to occur, although it does not

always result in disease (not necessarily

sufficient)

Risk factor - Increases the probability of a

particular disease/condition in a group of people

compared with an otherwise similar group of

people who lack this factor (neither necessary

nor sufficient)

�Variable Associations

�Variable Associations (Example)

�Bidirectional Causality

�Bidirectional

Causality

�Rate and Risk

A rate is a good approximation of risk if the:

Event in the numerator occurs only once

per individual during the study interval

Proportion of the population affected by the

event is small (e.g., less than 5%)

Time interval is relatively short

If the event in the numerator occurs more

than once during the study (e.g., colds, ear

infections, asthma attacks) a related statistic

called incidence density should be used

instead of rate

�Steps in Determining Cause

and Effect

1.Investigation of the statistical association

(Mills Canons)

1.Strength of association

2.Consistency

3.Specificity

4.Biological plausibility

5.Dose response

2.Investigation of the temporal relationship

. Latent periods make onset of risk factors

unclear

3.Elimination of alternative explanations

. Never eliminated fully or indefinitely;

challenged by each new explanation that fits

the data

�Only 4 Possibilities for Any

Association

1.Causal (true association)

2.Chance (based on probability)

3.Random error (non-differential error)

4.Systematic error (bias)

Confounding (special case of bias)

�Specific Types of Rates

�Specific Types of Rates

�Specific Types of Rates

�REFERENCES

1) Katz D, et al. Jekels Epidemiology, Biostatistics, Preventive Medicine,

and Public Health. 4th Ed. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA. 2014.

2) Daugherty S, et al. USMLE, Step 1, Behavioral Science, Epidemiology, &

Biostatistics. Becker Professional Education. 2013.

3) Brown T, Shah S. Biostatistics. USMLE STEP 1 SECRETS. 3rd Ed.

Saunders: Philadelphia, PA. 2013.

4) Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice: An Introduction to

Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Third Edition. Published 2006. Updated 2011. http://

www.cdc.gov/ophss/csels/dsepd/ss1978/index.html

5) Le T, et al. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, a Student to Student

Guide. McGraw Hill Education. 2014.

6) Glaser A. High Yield Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Public Health.

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 4th Ed. 2014. Ch 8.