Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fungal Rhinosinusitis

Uploaded by

igorOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fungal Rhinosinusitis

Uploaded by

igorCopyright:

Available Formats

MAIN ARTICLE

The Journal of Laryngology & Otology (2013), 127, 867871.

JLO (1984) Limited, 2013

doi:10.1017/S0022215113001680

Allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin

rhinosinusitis: diagnostic criteria

N URI1, O RONEN1, T MARSHAK1, O PARPARA1, M NASHASHIBI2, M GRUBER1

Departments of 1Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, and 2Pathology, Lady Davis Carmel Medical Center,

Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

Abstract

Background: Chronic sinusitis is one of the most common otolaryngological diagnoses. Allergic fungal sinusitis

and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis can easily be misdiagnosed and treated as chronic sinusitis, causing

continuing harm.

Aim: To better identify and characterise these two subgroups of patients, who may suffer from a systemic disease

requiring multidisciplinary treatment and prolonged follow up.

Methods: A retrospective, longitudinal study of all patients diagnosed with allergic fungal sinusitis or

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis within one otolaryngology department over a 15-year period.

Results: Thirty-four patients were identified, 26 with eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and 8 with allergic fungal

sinusitis. Orbital involvement at diagnosis was commoner in allergic fungal sinusitis patients (50 per cent) than

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients (7.7 per cent; p < 0.05). Asthma was diagnosed in 73 per cent of

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients and 37 per cent of allergic fungal sinusitis patients.

Conclusion: Allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis have the same clinical presentation

but different clinical courses. The role of fungus and the ability to confirm its presence are still problematic

issues, and additional studies are required.

Key words: Sinusitis; Fungus; Eosinophil; Mucin; Diagnosis

Introduction

Rhinosinusitis is defined as an inflammatory process

which involves the nasal and paranasal sinuses

mucosa. It is estimated that approximately 30 per cent

of the US population suffer from rhinosinusitis symptoms, and that the global cost of the disease is over 2

billion US dollars per year.1

The commonest cause of acute rhinosinusitis is

superimposed viral and bacterial infection. Chronic rhinosinusitis is linked to other aetiological factors such as

fungi, allergic reactions, mucociliary disorders, and

anatomical and systemic causes.

In recent years, the development of advanced diagnostic methods has facilitated research emphasising

the importance of fungal infections in chronic rhinosinusitis. In 1999, Ponikau and colleagues Mayo Clinic

group2 reported that 96 per cent of 210 chronic rhinosinusitis patients undergoing endoscopic sinus

surgery had a positive fungal culture, together with

signs of eosinophilic inflammation. Other study

groups described differing prevalences of positive

fungal cultures, ranging from 0 to 50 per cent.2,3

These findings support the theory that all types of

chronic rhinosinusitis are somehow related to a nonAccepted for publication 3 December 2012

allergic eosinophilic sinus inflammation secondary to

fungal infection.46

Fungal rhinosinusitis is divided into invasive and

non-invasive types. The category of invasive fungal

sinusitis includes acute invasive (fulminant) fungal

sinusitis, chronic invasive fungal sinusitis and granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis. Non-invasive fungal

sinusitis includes fungal ball (mycetoma), allergic

fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis.

Allergic fungal sinusitis was first described in 1983 as a

benign fungal disease of the sinuses in immunocompetent

patients.6 It has been estimated that this disease accounts

for 510 per cent of all patients with chronic rhinosinusitis.7 Two-thirds of allergic fungal sinusitis patients suffer

from allergic rhinitis, and approximately 90 per cent have

increased blood levels of immunoglobulin (Ig)

E. Allergic fungal sinusitis is common among adolescents and young adults, and is more common in geographical areas of high humidity. Two-thirds of patients

are atopic and half suffer from asthma.8

Allergic fungal sinusitis usually has an indolent

clinical course but late complications can occur, including proptosis, visual disturbances and facial

dysmorphism.

First published online 13 August 2013

868

There is no clear agreement regarding diagnostic criteria for allergic fungal sinusitis. In 1993, Loury et al.9

suggested criteria which included eosinophilia, elevated IgG or positive skin testing, elevated IgE for

fungal antigen, nasal polyps or nasal mucosal

oedema, typical computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, and histological evidence of allergic mucin, fungal hyphae and lack

of invasion. In 1994, Cody et al.10 reported the Mayo

Clinic experience, and suggested that diagnostic criteria comprise only the presence of allergic mucin

and fungal hyphae, or a positive fungal culture. One

of the most popular sets of criteria was published by

Bent and Kuhn in 1994.5 It was based upon five

elements: IgE-mediated hypersensitivity, polyposis,

typical CT scan findings, eosinophilic mucin, and positive fungal culture or staining. Kupferberg and Bent11

further classified allergic fungal sinusitis into stage 0

(no oedema or allergic mucin), stage I (oedematous

mucosa), stage II (polypoid oedema) and stage III

(polyps).

In most cases of allergic fungal sinusitis, dematiaceous fungi have been isolated, such as alternaria,

bipolaris, curvularia, drechslera, exserohilum and helminthosporium; a small proportion of aspergillus has

also been isolated.

Possible findings on CT scan include sinus opacification, bone destruction and thinning of the bony structures secondary to expansion of accumulated mucus.

Long-standing disease may present with dramatic

radiological findings such as invasion of the skull

base and orbit. Calcification within the sinuses is due

to the accumulation of elements such as iron and

manganese within the mucus.12

A suggested radiological staging system was published by Wise et al.13 in 2009, ranking each destroyed

bony element or expansile lesion and giving a score of

up to 24 points. Although CT scanning is suggested,

MRI scanning is an important adjunct when considering dural involvement or intracranial expansion.

Histological staining with haematoxylin and eosin

(H&E) highlights mucus and its cellular structures.

Allergic mucin, also termed eosinophilic mucin by

some, comprises over-produced mucus, eosinophils

and branching, non-invasive fungal hyphae.

Histological analysis shows fragmented eosinophils

and CharcotLeyden crystals, produced by eosinophil

breakdown.

Another useful histological staining is Gomori

methamine silver, which colours fungi brown-black.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining is negative when

few fungal hyphae are present; in this case, Gomori

methamine silver staining is important as it can delineate fungi when hyphae are sparse.

It should be emphasised that allergic fungal sinusitis

does not involve blood vessel or tissue invasion.

During follow up of allergic fungal sinusitis patients,

it is useful to monitor blood levels of IgE (specific to

the relevant fungal type) as a marker of recurrence.

N URI, O RONEN, T MARSHAK et al.

The mainstays of allergic fungal sinusitis treatment

are surgical and medical. The usual surgical treatment

is careful endoscopic debridement, followed by a

course of systemic corticosteroids. This treatment

lowers cytokine levels, which prevents the production,

activation and migration of eosinophils. Programmed

cell death is also induced. However, there is no published standard treatment protocol. Corticosteroid treatment usually extends for two to three months,

including gradual tapering of the dose, but there is currently no consensus regarding corticosteroid dosage or

duration.7,14,15

Other systemic therapies for allergic fungal sinusitis

have been proposed, but none has been clinically

proven.

Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis was first described

as a subtype of sinusitis which resembled allergic

fungal sinusitis clinically and histologically.

Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis has been defined as

a systemic disease, and therefore bilateral disease is

most common. In contrast, patients with allergic

fungal sinusitis have an allergic response to fungi,

which may occur unilaterally or bilaterally depending

on the antigenic stimulation. Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis is significantly associated with asthma, and an

increased incidence of aspirin sensitivity has also been

reported. Systemic corticosteroid is the treatment of

choice for eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis.

Computed tomography shows similar features to allergic fungal sinusitis (i.e. absence or destruction of the

medial nasal wall, hyperattenuation, and thinning of

sinus walls), but these are seen bilaterally in most

cases. The surgical appearance is of typical mucoid

material, with negative fungal cultures.16

The present study aimed to compare patients with

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and with allergic

fungal sinusitis, followed up in our rhinology clinic,

according to certain predetermined clinical criteria.

Differences between these two groups have been

rarely addressed, and there are few reports describing

patients with eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis.

Clarifying the criteria which differentiate these two

patient groups may facilitate quicker and more accurate

diagnosis, assisting timely and appropriate treatment.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective, longitudinal study

including all patients diagnosed with allergic fungal

sinusitis or eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis in the otolaryngology department of Carmel Medical Center,

Haifa, Israel, over a 15-year period (19962010).

Thirty-four patients were included in the study

cohort: 26 with eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and

8 with allergic fungal sinusitis. All patients were operated upon by the same surgeon.

Allergic fungal sinusitis was diagnosed according to

the criteria of Bent and Kuhn, as mentioned above. The

diagnosis of eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis was

based on the presence of extensive, polypoid disease

ALLERGIC FUNGAL SINUSITIS DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

with thick, eosinophilic mucus and no fungal hyphae,

as described in the pathological report. Eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients were monitored in our rhinology clinic before and after surgery; during this time

period, no fungus was identified from various cultures

and pathological specimens. Wegeners disease and

ChurgStrauss disease were tested for and excluded

in all patients.

Information was collected from the following

sources, for all patients: demographic data; physical

examination and nasal endoscopy; CT scans; pathology

reports (all patients had pathological specimens collected during surgery, and all such specimens were

reviewed again by the pathologist and the surgeon);

bacteriological reports; surgical records; and data on

medical treatments, recurrences and follow-up times.

This study was approved by the institutional ethical

review board.

Results and analysis

Demographical and clinical parameters were compared, using Fishers exact test for continuous variables

and Students t-test for discrete variables.

Analysis was performed for 26 patients with eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and 8 patients with allergic

fungal sinusitis.

Mean age was greater for the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients (55.9 years) than the allergic fungal

sinusitis patients (34.5 years old) ( p < 0.0001).

Disease was bilateral in 91.6 per cent of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients and 62.5 per cent of allergic fungal sinusitis patients ( p < 0.05). Nasal obstruction was demonstrated in 34.6 per cent of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients and 100 per cent of allergic fungal sinusitis patients ( p < 0.05). Nasal discharge was demonstrated in 57.7 and 37.5 per cent of

the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and allergic

fungal sinusitis patients, respectively.

More allergic fungal sinusitis patients (50 per cent)

had orbital involvement at diagnosis, compared with

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients (7.7 per

cent; p < 0.05). The lamina papyracea was involved

by the disease process in 50 per cent of allergic

fungal sinusitis patients and 15 per cent of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients, a statistically significant

difference ( p < 0.05).

Asthma was diagnosed in 7 per cent of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients and 37 per cent of allergic

fungal sinusitis patients, although this difference was

not statistically significant.

Endoscopic surgery was undertaken for all patients.

Some cases were managed with a navigation system to

enhance safety, especially when operating upon extensive and destructive lesions (e.g. orbital involvement

and frontal sinus surgery).

Most patients needed more than one surgical procedure during the study period; the mean and median

number of surgical procedures were respectively 3.3

and 2 for the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients,

869

and 1.4 and 1 for the allergic fungal sinusitis patients

(the difference between means was not statistically

significant).

Histological examination utilised H&E (Figure 1),

periodic acid Schiff and Gomori methamine silver

stains. Fungi were identified in 87.5 per cent of the

allergic fungal sinusitis histological block specimens,

and none of the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis

specimens.

All patients were available for follow up during the

study period. The mean (median) follow-up periods

were 9.7 (10 years) for the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients and 8 years (8 years) for the allergic

fungal sinusitis patients.

Table I summarises results for the two groups.

Discussion

It is important to identify the common elements

between the different forms of eosinophilic sinusitis,

in order to better define and subclassify this condition.

Ferguson17 reported substantial clinical and immunological differences between allergic fungal sinusitis

and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis. Aetiologically,

FIG. 1

Photomicrographs showing eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis.

(H&E; 20)

870

N URI, O RONEN, T MARSHAK et al.

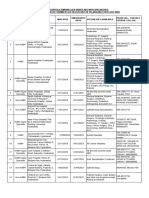

TABLE I

PATIENT DATA

Parameter

Total (n)

Age (mean (median); yr)

Males (n (%))

Females (n (%))

Bilateral disease (n (%))

Orbital involvement

(n (%))

IgE (mean; U/ml)

Asthma (n (%))

ESS (mean (median, SD); n)

AFS

EMRS

8

34.5 (31.5)

4 (50)

4 (50)

5 (62.5)

4 (50)

26

55.9 (57.0)

15 (57.7)

11 (42.3)

25 (96.1)

2 (7.7)

>500

3 (37.5)

1.4 (0.5, 1.7)

220.4

19 (73.1)

3.3 (2, 2.7)

AFS = allergic fungal sinusitis; EMRS = eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis; yr = years; Ig = immunoglobulin; ESS = endoscopic

sinus surgery; SD = standard deviation

allergic fungal sinusitis is based on the presence of an

immunological allergic reaction to fungi in predisposed

individuals. This tissue reaction results in the production of allergic mucus rich in eosinophils and

non-invasive fungi, together with marked elevation of

blood levels of specific IgE antibodies. Ferguson

believed that eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis represented a local immune reaction occurring secondary

to a systemic disorder.17 In most such cases, IgE

levels are within normal limits, with no observed

fungi, in contrast to allergic fungal sinusitis patients,

who present with elevated IgE due to fungal growth.

According to these basic differences, it is reasonable

to divide chronic rhinosinusitis patients into two

groups: fungal and non-fungal. The fungal subgroup

consists mainly of allergic fungal sinusitis patients.

The non-fungal subgroup consists of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients and patients with sinusitis

and aspirin-sensitive asthma (which deteriorates when

treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

such as aspirin).

Thick, eosinophilic mucus rich in inflammatory

debris is the hallmark of allergic fungal sinusitis.

When identified, it is the first clue that the surgeon

and pathologist should search for the presence of

fungus. But is such fungal presence the defining parameter for subgroup classification?

Another theory proposes that the first stage of

disease is the allergic reaction which prompts eosinophilic mucus production, while the second stage is

the antigenic reaction to the fungi trapped by this allergic reaction. This theory actually refers to the fungi as a

by-product, and known responses to various treatments

support this opinion. No anti-fungal treatments have

been proven to change the course of the disease. This

argument was further reinforced by a 2011 Cochrane

database review which concluded that there were no

data to support the use of such treatments.18

In 2007, Orlandi et al.19 investigated a different perspective concerning the expression of certain genes.

They examined DNA from allergic fungal sinusitis

patients, eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients

and healthy controls. Four genes were found to be

expressed in eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis but not

in allergic fungal sinusitis, coding for S-100 calciumbinding protein, cathepsin B, sialytransferase 1 and

ganglioside activator protein (GM2). These genes

are responsible for lysosomal activity and act as

mediators of inflammatory and tumoural processes.

Orlandi et al. suggested that the genetic profiles of

allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis were similar, although differences existed

and needed to be further clarified.

Ponikau et al.2 also investigated the role of fungi in

chronic sinusitis. In their study, fungus was present in

almost all hospital chronic sinusitis patients, as well

as in healthy controls. This finding questions the

nature of fungi in the aetiology of allergic fungal

sinusitis.

Most of the data on the clinical and immunological

differences between allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis have been derived from

Fergusons 2000 study.17 This author compared previously published data on 418 allergic fungal sinusitis

patients and 40 eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis

patients, together with information from a further 13

allergic fungal sinusitis patients and 29 eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients from the authors own

database. In the latter database, 41 per cent of allergic

fungal sinusitis patients and 93 per cent of eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis patients suffered from asthma; in

our study cohort, the prevalence of asthma was 37.5

and 75 per cent, respectively. In Fergusons study,

the mean patient age was 30 years in the allergic

fungal sinusitis group and 48 years in the eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis group; in comparison, our

patients mean ages were 34.5 and 55.9 years, respectively. In Fergusons own cohort, bilateral disease was

present in 55 per cent of allergic fungal sinusitis

patients and 100 per cent of eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients, similar to our own data.

In our cohort, orbital complications were more

common among allergic fungal sinusitis patients (50

per cent) than eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis

patients (8 per cent). These orbital complications presented as diplopia, proptosis and lamina papyracea

destruction. This finding suggests a more aggressive

behaviour for allergic fungal sinusitis, and justifies

special clinical attention for this subgroup of patients.

The number of surgical procedures differed between

our two patient groups, with a mean of 1.4 procedures

for allergic fungal sinusitis patients but 3.3 procedures

for eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis patients, although

this difference was not statistically significant.

We cannot report accurate data on recurrence among

our eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis and allergic

fungal sinusitis patients. We found that patients who

presented with relevant symptoms and signs were

first diagnosed with allergic fungal sinusitis; only

later, after additional data collection from histological

analysis and fungal cultures, was the diagnosis of

871

ALLERGIC FUNGAL SINUSITIS DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis considered. In some

cases, eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis was suspected

only after multiple surgical procedures and several

relapses, and only at that stage did the patient begin

to receive appropriate, systemic therapy.

Allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis are easily misdiagnosed,

hindering effective treatment

They have the same initial clinical

presentation but different clinical courses

Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis is usually

bilateral, and surgical treatment more

common

Allergic fungal sinusitis is prone to early

orbital involvement

In both, the role of fungi, and diagnostic

protocols, are unclear

Establishing diagnostic criteria to differentiate between

allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis is difficult. The presence of fungi is essential,

and the identification of the culprit is only possible

through the use of appropriate stains. It is possible

that some of our patients diagnosed with eosinophilic

mucin rhinosinusitis actually had allergic fungal sinusitis but that no fungi were identified. We emphasise

that the use of Gomori methamine silver staining is

essential to the diagnosis: the use of H&E staining

alone is inadequate.

Another difficulty in preparing fungal cultures from

sinus secretions arises from the differing culture protocols followed by different laboratories. This discrepancy probably explains a significant amount of the

observed variance in positive fungal culture rates:

various studies have reported rates of between 10 and

97 per cent.

Conclusion

Allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis have the same initial clinical presentation,

although they are different diseases with (usually) differing clinical courses. Our results indicate higher

complication rates and fewer surgical procedures in

the allergic fungal sinusitis subgroup, compared with

the eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis subgroup. More

specifically, the clinical course of allergic fungal sinusitis seems to be more aggressive, with a higher prevalence of orbital complications and greater associated

morbidity. The role of fungus and the ability to

confirm its presence are still problematic issues.

Additional studies are required to investigate aetiology,

diagnostic standardisation and patient care.

References

1 Lucas JW, Schiller JS, Benson V. Summary health statistics for

U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2001. Vital

Health Stat 10 2004;218:1134

2 Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kern EB, Homburger HA, Frigas E,

Gaffey TA et al. The diagnosis and incidence of allergic

fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc Sep 1999;74:87784

3 Corey JP. Allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am

1992;25:22530

4 Millar J, Lamb D. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis of

the maxillary sinuses. Thorax 1981;36:710

5 Bent JP 3rd, Kuhn FA. Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;111:5808

6 Katzenstein AL, Sale SR, Greenberger PA. Pathologic findings

in allergic aspergillus sinusitis. A newly recognized form of

sinusitis. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:43943

7 Schubert MS. Allergic fungal sinusitis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Med Mycol 2009;47:32430

8 Manning SC, Holman M. Further evidence for allergic pathophysiology in allergic fungal sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1998;

108:148596

9 Loury MC, Leopold DA, Schaefer SD. Allergic aspergillus

sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:10423

10 Cody DT 2nd, Neel HB 3rd, Ferreiro JA, Roberts GD. Allergic

fungal sinusitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Laryngoscope

1994;104:10749

11 Kupferberg SB, Bent JP. Allergic fungal sinusitis in the pediatric

population. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:

13814

12 de Shazo RD, OBrien M, Chapin K, Soto-Aguilar M, Swain R,

Lyons M et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of sinus mycetoma.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99:47585

13 Wise SK, Rogers GA, Ghegan MD, Harvey RJ, Delgaudio JM,

Schlosser RJ. Radiologic staging system for allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140:

73540

14 Schubert MS, Goetz DW. Evaluation and treatment of allergic

fungal sinusitis. I. Demographics and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1998;102:38794

15 Rupa V, Jacob M, Mathews MS, Seshadri M. A prospective,

randomised, placebo-controlled trial of postoperative oral

steroid in allergic fungal sinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol

2010;267:2338

16 Katzenstein AL, Sale SR, Greenberger PA. Allergic aspergillus

sinusitis: a newly recognized form of sinusitis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1983;72:8993

17 Ferguson BJ. Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis: a distinct clinicopathological entity. Laryngoscope 2000;110:799813

18 Sacks PL, Harvey RJ, Rimmer J, Gallagher RM, Sacks R.

Topical and systemic antifungal therapy for the symptomatic

treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2011;(8):CD008263

19 Orlandi RR, Thibeault SL, Ferguson BJ. Microarray analysis of

allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:70713

Address for correspondence:

Dr Maayan Gruber,

Department of Otolaryngolgy Head and Neck Surgery,

Lady Davis Carmel Medical Center,

7 Michal St, Haifa 34362, Israel

E-mail: maayan_gr@yahoo.com

Dr M Gruber takes responsibility for the integrity

of the content of the paper

Competing interests: None declared

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Pediatric Physiology 2007Document378 pagesPediatric Physiology 2007Andres Jeria Diaz100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Human Body PDFDocument9 pagesHuman Body PDFAnonymous W4MMefmCNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal Trauma 2Document61 pagesLaryngeal Trauma 2igor100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Pediatric Surgery Second EditionDocument893 pagesFundamentals of Pediatric Surgery Second EditionPatricia Beznea100% (3)

- Young Mania Rating Scale-MeasureDocument3 pagesYoung Mania Rating Scale-MeasureSelvaraj MadhivananNo ratings yet

- PAROTID GLAND NEOPLASM IMAGINGDocument107 pagesPAROTID GLAND NEOPLASM IMAGINGigorNo ratings yet

- MELANOMA: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Staging and TreatmentDocument25 pagesMELANOMA: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Staging and TreatmentFazaKhilwanAmnaNo ratings yet

- Orphan Lung DiseasesDocument623 pagesOrphan Lung Diseasescarmen84100% (1)

- Allergic Fungal Sinusitis PresentationDocument50 pagesAllergic Fungal Sinusitis PresentationdrdrsuryaprakashNo ratings yet

- Last Minute RevisionDocument108 pagesLast Minute RevisionRahul All83% (6)

- Practice Test Pediatric Nursing 100 ItemsDocument17 pagesPractice Test Pediatric Nursing 100 ItemsKarla FralalaNo ratings yet

- LIST OF HOSPITALS EMPANELLED UNDER ABS WITH SPECIALITIESDocument17 pagesLIST OF HOSPITALS EMPANELLED UNDER ABS WITH SPECIALITIESprem kumarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Facial Fracture FINALDocument70 pagesPediatric Facial Fracture FINALigorNo ratings yet

- Cortical ERADocument37 pagesCortical ERAigorNo ratings yet

- Cogan SindromDocument4 pagesCogan SindromigorNo ratings yet

- Anosmia in COVID-19: Underlying Mechanisms and Assessment of An Olfactory Route To Brain InfectionDocument22 pagesAnosmia in COVID-19: Underlying Mechanisms and Assessment of An Olfactory Route To Brain InfectionigorNo ratings yet

- Fix Journal 1Document14 pagesFix Journal 1Lavenia Ellein MokiwangNo ratings yet

- Upper Airway and Digestive Tract Anatomy and PhysiologyDocument41 pagesUpper Airway and Digestive Tract Anatomy and PhysiologyigorNo ratings yet

- Fix Journal 1Document14 pagesFix Journal 1Lavenia Ellein MokiwangNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal TraumaDocument16 pagesLaryngeal TraumaigorNo ratings yet

- Ipi404109 PDFDocument5 pagesIpi404109 PDFigorNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal TraumaDocument16 pagesLaryngeal TraumaigorNo ratings yet

- Principles of ChemotherapyDocument31 pagesPrinciples of Chemotherapyigor100% (1)

- Responses of CD4Document10 pagesResponses of CD4igorNo ratings yet

- Allergic Rhinitis in Children Diagnosis and ManagementDocument18 pagesAllergic Rhinitis in Children Diagnosis and ManagementigorNo ratings yet

- SCITDocument12 pagesSCITigorNo ratings yet

- Chelladurai 2014Document5 pagesChelladurai 2014igorNo ratings yet

- Allergen ImmunotherapyDocument23 pagesAllergen ImmunotherapyigorNo ratings yet

- 10.1158@0008 5472.can 16 2345Document25 pages10.1158@0008 5472.can 16 2345igorNo ratings yet

- OtosclerosisDocument85 pagesOtosclerosisigorNo ratings yet

- Felder 2014Document15 pagesFelder 2014igorNo ratings yet

- Bar To Lazzi 2008Document7 pagesBar To Lazzi 2008igorNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of OMDocument18 pagesPathophysiology of OMigorNo ratings yet

- 2 - Rhinitis - Carmen RondonDocument35 pages2 - Rhinitis - Carmen RondonigorNo ratings yet

- ICD 9 Dan 10 THT-KLDocument30 pagesICD 9 Dan 10 THT-KLigorNo ratings yet

- Papadopoulos Et Al 2015 AllergyDocument21 pagesPapadopoulos Et Al 2015 AllergyigorNo ratings yet

- GA LEN/EAACI Pocket Guide For Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy For Allergic Rhinitis and AsthmaDocument6 pagesGA LEN/EAACI Pocket Guide For Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy For Allergic Rhinitis and AsthmaYohana VeronicaNo ratings yet

- C A Shinkwin Bon Secours GP Study Day 28 JANUARY, 2012Document23 pagesC A Shinkwin Bon Secours GP Study Day 28 JANUARY, 2012Nila HapsariNo ratings yet

- Congenital Muscular TorticollisDocument29 pagesCongenital Muscular Torticolliskashmala afzal100% (1)

- CNPASDocument3 pagesCNPASaneeshNo ratings yet

- Nurse Education in Practice: Book ReviewsDocument1 pageNurse Education in Practice: Book ReviewsUswatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Mouth Breathing A Menace To Developing DentitionDocument7 pagesMouth Breathing A Menace To Developing DentitionLia CucoranuNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Jurnal-Traksi PDFDocument5 pagesDokumen - Tips Jurnal-Traksi PDFPrilii Ririie 'AnandaNo ratings yet

- Wvsu MC Org ChartDocument1 pageWvsu MC Org ChartquesterNo ratings yet

- Sex HDDocument2 pagesSex HDm29hereNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Conduction ExplainedDocument4 pagesCardiac Conduction ExplainedCharli VilcanNo ratings yet

- Topical Atropine Mydriasis RabbitDocument3 pagesTopical Atropine Mydriasis RabbitPadmanabha Gowda100% (1)

- Premature Rupture of MembranesDocument9 pagesPremature Rupture of MembranesYessica MelianyNo ratings yet

- AmalgamDocument3 pagesAmalgamMira AnggrianiNo ratings yet

- Melomed Pregnancy JournalDocument24 pagesMelomed Pregnancy JournalCelvin SohilaitNo ratings yet

- Assistant Professors: 327 2. C: (Vacancies Are Likely To Increase or Decrease)Document4 pagesAssistant Professors: 327 2. C: (Vacancies Are Likely To Increase or Decrease)JeshiNo ratings yet

- Apex LocatorsDocument6 pagesApex LocatorsbanupriyamdsNo ratings yet

- PPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPDocument4 pagesPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPNor Ubudiah SetiNo ratings yet

- Folder Flexya Ita Pag AffiancateDocument2 pagesFolder Flexya Ita Pag AffiancateemikyNo ratings yet

- Medical PREFIXES and SUFIXESDocument52 pagesMedical PREFIXES and SUFIXESThirdz TylerNo ratings yet

- SDSC Eng ColourDocument2 pagesSDSC Eng ColourmerawatidyahsepitaNo ratings yet

- Tetric N-CollectionDocument8 pagesTetric N-CollectionRizky Ananda PutriNo ratings yet

- Burkitt's LymphomaDocument22 pagesBurkitt's LymphomaClementNo ratings yet

- DR - VM.Thomas - Consultant EmbryologistDocument2 pagesDR - VM.Thomas - Consultant EmbryologistdrthomasfertilitycenterNo ratings yet