Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MC3 2 No9

Uploaded by

Marlo Anthony BurgosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MC3 2 No9

Uploaded by

Marlo Anthony BurgosCopyright:

Available Formats

Mycosphere Doi 10.

5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

An ethnomycological survey of macrofungi utilized by Aeta communities in

Central Luzon, Philippines

De Leon AM1,3, Reyes RG3 and dela Cruz TEE1,2*

1

Graduate School, and 2 Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Espaa

1015 Manila, Philippines

3

Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, Central Luzon State University, 3120 Science City

of Muoz, Nueva Ecija, Philippines

De Leon AM, Reyes RG, dela Cruz TEE An ethnomycological survey of macrofungi utilized by

Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Philippines. Mycosphere 3(2), 251-259, Doi

10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

Questionnaires and formatted interviews were used to determine mushrooms used as food and as

materials for societal rituals and beliefs among six Aeta communities in three provinces of Central

Luzon, Northern Philippines. Thirty-eight different fungi were utilized by the Aeta communities: 21

in Pampanga, 10 in Tarlac, and 19 in Zambales. Fourteen fungal species were collected and

identified based on their morphological characters: Auricularia auricula, A. polytricha, Calvatia

sp., Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinus tigrinus, L. sajor-caju, Mycena sp., Pleurotus sp., Schizophyllum

commune, Termitomyces clypeatus, T. robustus, Termitomyces sp. 1, Termitomyces sp. 2, and

Volvariella volvacea. Twelve of the identified macrofungi were consumed as food while

Ganoderma lucidum and Mycena sp. were used as house decoration and medicine, respectively.

The Aeta communities also performed rituals prior to the collection of these mushrooms, including

tribal dancing, praying and kissing the ground. Their indigenous beliefs regarding mushrooms are

also documented. This is the most extensive enthnomycological study on the Aeta communities in

the Philippines.

Key words edible fungi ethnomycology indigenous communities macrofungi

Article Information

Received 8 March 2012

Accepted 6 April 2012

Published online 30 April 2012

*Corresponding author: tedelacruz@mnl.ust.edu.ph / thomasdelacruz@yahoo.com

Introduction

The Philippines is a culturally diverse

country with an estimated 1215 million

indigenous people (IPs) belonging to 110

ethno-linguistic groups (Waddington 2002).

The indigenous people constitute 1015% of

the population of the country. They are mainly

found in Northern Luzon and Mindanao, with

some groups in the Visayas area (UNDP 2010).

Among the major groups of IPs are the Igorot

of Northern Luzon, the Lumads of Mindanao,

the Mangyans of Mindoro, and the Negritos

living in different regions of the country. The

Negritos migrated from mainland Asia and

settled in the Philippines around 30,000 years

ago (Cario 2010). Their main tribal groups

include the Ati found in Panay, the Agta in

Bicol, and the Aeta in Luzon.

The Aetas of Luzon are nomadic

people. Their social activities revolve around

hunting of birds, frogs, and other animals, and

gathering of fruits, insects, and mushrooms

(Shimizu 1989). Mushrooms also provide

additional incomes to households if sold in

251

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

Fig. 1 Map of Central Luzon showing the three study sites.

(1) Floridablanca, Pampanga:

Site 1: Brgy. Mawacat (14 58' 26" N, 120 26' 9" E, AD), Aeta population is 1,500.

Site 2: Brgy. Nabuclod (15 1' 1" N, 120 26' 36" E, RA), Aeta population is 620.

The Aeta sub-tribe living in this province are the Mag-indi.

(2) Capas, Tarlac:

Site 1: Brgy. Yeyoung (15 19' 32" N, 120 25' 1" E, AD), Aeta population is 396.

Site 2: Brgy. Kalangitan (15 18' 46" N, 120 31' 11" E, RA), Aeta population is 2,940.

The sub-tribe of the Aetas in this province are the Mag-antsi.

(3) Botolan, Zambales:

Site 1: Brgy. Bucao (15 15' 28" N, 120 1' 51" E, AD), Aeta population is 1,570.

Site 2: Brgy. Bihawo (15 19' 8" N, 120 2' 46" E, RA), Aeta population is 1,020.

Aeta communities in this province belong to the sub-tribe Zambal.

regional markets (Yongabi et al. 2004). In the

Philippines, IPs were known to utilize

macrofungi species for various purposes

(Tayamen et al. 2004). However, few

published reports document the exact number

of macrofungi utilized by these communities.

Hence, their indigenous knowledge is poorly

documented and not systematically recorded. It

is therefore of urgency to properly document

this traditional knowledge before it is lost.

Thus, our study surveyed and documented the

utilization of macrofungi by six Aeta

communities in selected areas of Central

Luzon.

Methods

Study Sites

Six sites in three provinces (Pampanga,

Tarlac and Zambales) in Central Luzon,

Northern Philippines served as the study sites

(Fig. 1). In each province, one of the study

communities surveyed was Aeta tribe in their

ancestral domain (AD) while the other tribe

was in a resettlement area (RA). Those in the

resettlement areas were Aetas displaced by the

eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991.

The respondents

The Aetas are the earliest inhabitants of

the Philippines. Their estimated population is

around 140,500 individuals. In Central Luzon,

they dwell mainly on mountain slopes in the

provinces of Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga,

Tarlac, and Zambales. Many of the Aetas

living in Nueva Ecija and some towns in

Pampanga, Tarlac and Zambales previously

lived on the slopes of Mt. Pinatubo but were

now in resettlement areas. They regarded the

mountain, as the home of their supreme deity,

252

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

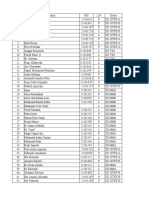

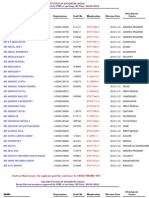

Table 1 Socio-demographic profiles of the surveyed six Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Northern Philippines.

Province

Study Site

Pampanga Mawacat

Nabuclod

Tarlac

No. of

Age

Gender

Civil Status

Educational Attainment

Religion

NonSub-Tribe Respondents 16- 26- 46- Male Female Married Single College Vocational High Elementary No Catholic

25 45 up

School

Ans.

Catholic

MagIndi

MagIndi

Yeyoung MagAntsi

Kalangitan MagAntsi

Zambales Bucao

Bihawo

Zambal

Zambal

30

30

2

15

20

13

8

2

26

3

4

27

26

27

4

3

0

1

0

0

1

5

12

16

17

8

21

8

9

22

30

30

9

0

12

21

9

9

11

21

19

9

21

27

7

3

2

3

0

2

6

10

10

15

12

0

0

11

30

19

30

30

8

5

12

14

10

11

12

6

18

24

25

27

5

3

0

1

1

0

12

4

16

21

1

4

20

26

10

4

Table 2 Survey on the knowledge of mushroom by the six Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Northern Philippines.

Province

Site

Sub-Tribe

No. of

Respondents

Do you know

Mushroom?

Yes

No No Ans.

Pampanga Mawacat

Nabuclod

MagIndi

MagIndi

30

30

25

24

0

4

5

2

Tarlac

MagAntsi

MagAntsi

Zambal

Zambal

30

30

30

30

30

30

24

30

0

0

4

0

0

0

2

0

Yeyoung

Kalangitan

Zambales Bucao

Bihawo

When do mushrooms

Where do mushrooms appear?

appear?

When

When

When Decaying Leaf

Soil

No

its

its hot its cold

Logs

Litter

Ans.

raining

30

9

27

27

26

27

1

30

0

0

21

3

21

2

30

30

30

30

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

10

29

23

10

9

253

1

23

3

1

30

27

25

30

0

16

1

7

How Mushrooms are

Utilized?

Food Medicine

No

Ans.

27

29

0

4

3

0

30

30

29

30

0

10

2

0

0

0

1

1

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

Apo Namalyari. The Aetas are divided into

seven sub-tribes according to their dialect.

These are: (1) Mag-Indi (Pampanga), (2) MagAntsi (Tarlac), (3) Zambal (Zambales) (4)

Ambala (Bataan), (5) Kabayukan (Bataan), (6)

Kaunana (Bataan), and (7) Magbekin or

Magbukon (Bataan).

Survey Questionnaire and Interview

Initially, a letter was given to the tribal

heads in the study sites requesting permission

to conduct research in their areas. A permit was

also secured from the National Commission on

Indigenous People (NCIP) of the Republic of

the Philippines. A meeting was then held with

the tribal heads and elders in each of the Aeta

communities for the conduct of the survey

questionnaires and interview.

Information asked in the questionnaires

included: socio-demographic data, knowledge

on mushrooms, and beliefs and practices on

mushroom collection and cultivation. The

survey questionnaires were given to 30

respondents per study site (aged 16 and above).

Formatted interviews of the tribal chieftains

and other elders were also done to gather more

data on the mushrooms they utilized and their

traditions. During the collection of specimens,

the tribal heads and other members of the tribe

including a representative from NCIP joined

the field collection and provided additional

information.

Collection and Identification of Specimens

All visibly present macrofungi utilized

by the Aeta communities were collected during

the rainy season (from May to October 2011)

with the assistance of the tribal chieftains and

other tribe members. Specimens were initially

photographed in their habitat, collected and

placed in bags, then taken to the laboratory for

identification. For fleshy specimens, samples

were preserved in 95% ethanol. Other

specimens, particularly the polypore fungi,

were air-dried and prepared as herbarium

specimens. Fruiting body morphologies

including cap size, cap description, etc. were

determined for each of the specimens. A spore

print was made from fleshy mushrooms while

sectioning

was

done

for

non-fleshy

mushrooms. Identification was made by

comparing morphologies with published

literature, e.g., Quimio (2001), Lodge et al.

(2004).

Data analysis

The socio-demographic profiles of the

respondents in the six Aeta communities were

tabulated to provide basic information on the

respondents. The number of identified fungi

recorded in the survey questionnaire was

determined for each of the sub-tribes. The

mushrooms reported in the questionnaires were

correlated or compared with the collected

specimens. A list of the different fungal species

and their local names and utilization was

prepared from the study.

Results and Discussion

Socio-demographic profiles

Most of the Aeta respondents were 2645 years old, female, married and with

Catholicism as their main religion (Table 1).

This is also true with most of the IPs found in

Northern Luzon (Cabauatan 2008). Many of

the respondents also reached only elementary

level in their education. This was attributed to

poverty. The situation is also very similar with

most of the IPs in the Philippines (NCIP 2009).

Indigenous Knowledge on Mushrooms and

their Utilization

Most of the Aeta respondents,

regardless of their tribal affiliation and present

settlement area, knew about mushrooms (Table

2). All sub-tribes believed that mushrooms

appear when it rained. However, three subtribes, i.e. the Mag-Indi in Brgy. Mawacat,

Pampanga, the Mag-Antsi in Brgy. Kalangitan,

Tarlac, and the Zambal in Brgy. Bihawo,

Zambales, believed that mushrooms appear

also during the cold months (December

January) and/or hot months (MarchApril).

This observation was supported by Reyes et al.

(2003) wherein mushrooms could grow

anytime of the year in the Philippines as long

as present or growing in moist areas. Tayamen

et al. (2004) noted that some species grew only

after heavy downfall. The Aeta respondents

believed that mushrooms grow in soil,

decaying logs, and leaf litter (Table 2).

254

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

Table 3 Mushrooms reported by the Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Northern Philippines

based on the survey-questionnaires, interviews, and collected specimens.

Local Names

Scientific Names

Kuwat Amucao

Volvariella volvacea

Kuwat Anglap/Papait

Mycena sp.

Kuwat Aray

nc

Kuwat Awili

nc

Kuwat Balite

nc

Kuwat Bayto

Nc

Kuwat Baytuat

nc

Kuwat Bola/Duldul

Calvatia sp.

Kuwat Gilatgilatan

Termitomyces clypeatus

Kuwat Ginikan/Saging

Volvariella volvacea

Kuwat Hanggilit

Schizophyllum commune

Kuwat Kahoy

Ganoderma lucidum

Kuwat Karael

nc

Kuwat Kasoy

Pleurotus sp.

Kuwat Kawayan

Lentinus sajor-caju

Kuwat Kikitban

Lentinus tigrinus

Kuwat Kogon

nc

Kuwat Kuritdit

Schizophyllum commune

Kuwat Kuyog

Termitomyces clypeatus

Kuwat Lupa/Uong

Termitomyces clypeatus

Kuwat Malakamawey

Termitomyces robustus/ Termitomyces sp.2

Kuwat Malakamay

Termitomyces robustus/ Termitomyces sp.2

Kuwat Mangga

ni

Kuwat Maya

Nc

Kuwat Mayo

Termitomyces sp. 1

Kuwat Miyapol

Lentinus tigrinus

Kuwat Puking Buykan

Nc

Kuwat Pulelen

ni

Kuwat Punso

Termitomyces clypeatus

Kuwat Puyo

nc

Kuwat Susong Biik

Nc

Kuwat Tagyang Biklat

Nc

Kuwat Malabalugbog dagis/Kuling baki Auricularia auricula/A. polytricha

Kuwat Takaclomuwag

nc

Kuwat Takbulaw

Nc

Kuwat Taklabaw

Nc

Kuwat Tangkiki

Auricularia auricula/A. polytricha

Kuwat Titiwbaboy

Nc

Total

nc = mushrooms not present during the sampling period

ni = collected mushrooms, could not be identified

The Aetas collect mushrooms mainly

for food and rarely for medicine and other

purposes (Table 2). The cooking method

preferred by the Aetas for nearly all edible

mushrooms were sauted or boiled with other

vegetables and fermented fish sauce.

Unfortunately, there are no other reported

researches on the ethnomycology of other IPs

in the Philippines so our result cannot be

compared to see if other IPs also shares the

Mag-Indi Mag-Antsi Zambal

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

21

10

19

same beliefs. In Guyana, the cooking method

preferred by the Patamona indigenous tribe

was steaming the mushroom in leaves collected

in the forests (Henkel et al. 2004).

Listing of Mushrooms Utilized by the Aetas

There were 38 records of macrofungi

that are utilized by the different Aeta subtribes: 21 fungal records in Pampanga, 10 in

Tarlac, and 19 in Zambales (Table 3).

255

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

However, during the entire duration of the

mushroom collection from May to October

2011, only 14 fungal species were encountered,

collected and identified (Table 3). Twelve

species were utilized as food: Auricularia

auricula, A. polytricha, Calvatia sp., Lentinus

tigrinus, L. sajor-caju, Pleurotus sp., Schizophyllum commune, Termitomyces clypeatus, T.

robustus, two species of Termitomyces, and

Volvariella volvacea (Table 4).

IPs from the African continent eat

about 300 species of fungi (Rammeloo &

Walleyn 1993). Fungal species were also used

by indigenous people as food in Mexico

(Garibay-Orijel et al. 2006, Montoya et al.

2004), Malaysia (Christensen & Larsen 2005),

and Papua New Guinea (Sillitoe 1995). In

Africa, various kinds of wild edible

mushrooms were found, of which 15 to 25

species were locally well known and eaten

throughout Zambia (Pegler & Pierce 1980).

Many of these were also sold in market places.

For example, Auricularia polytricha is consumed in many African regions, more particularly in Nigeria. Other species of edible

mushrooms found in Africa included Agrocybe

spp., Boletus spp., Canthareullus spp., Calvatia

spp., Coprinus spp., Lactaricus kabansus, L.

inversus, L. piperatus, L. edulis, Lentinus cladopus, L. squarosulus, L. tuber-regium,

Macrolepiota procera, M. zeyheri, Pleurotus

squarrosulus, Psathyrella atroumbonata, P.

candolleana, Russula spp., Schizophyllum

commune, Terfezia boudieri, T. claveryi, T.

pfeilii, Termitomyces microcarpus, T. clypeatus, T. shimperi, T. titanicus, T. auratiacus, T.

globu-lus, T. eurhizus, T. robustus, Tricholoma

loba-yense, T. matsutake, Volvariella volvacea,

V. esculenta, and V. speciosa (Labarere &

Gemini 2000). Of these, A. polytricha, S.

commune, T. clypeatus, T. robustus, and V.

volvacea were also reported as edible

mushrooms by the Aeta communities (Table

4).

In Zambales, one sub-tribe (Zambal)

reported that Ganoderma lucidum was used for

house decoration while in Pampanga, a species

of Mycena was used as medicine by the subtribe Mag-Indi (Table 5). In Germany, a new

metabolite extracted from Mycena sp. was

found to be active against bacteria and fungi

(Sheldrik 1990). Ganoderma lucidum, on the

other hand, is utilized mostly as medicine and

no previous research cites its use as a

household decoration.

Twenty-one local names for several

mushroom species were used by sub-tribe

Mag-Indi, 10 by sub-tribe Mag-Antsi, and 19

by sub-tribe Zambal (Table 3). However, all

mushrooms are generally known as kuwat by

all Aeta sub-tribes and thus, names for specific

species of mushrooms always have this term as

a prefix.

Interestingly, we observed similarities

in local names given to mushrooms (Table 4).

For example, Termitomyces sp. 1, which grows

only in May, was locally called by all the subtribes as kuwat mayo. Mayo is the local

term for the month of May. It is also interesting

to note that the different Aeta communities also

used different local names for similar species

of mushrooms (Table 4). For example, the subtribe Zambal from Zambales used kuwat

gilatgilatan as local name for Termitomyces

clypeatus. On the other hand, sub-tribe MagIndi from Pampanga used kuwat uong while

sub-tribe Mag-Antsi from Tarlac used kuwat

kuyog as the local name for this fungal

species. They also used same local names for

different species of mushrooms, e.g.

Termitomyces sp. 2 and Termitomyces robustus

were both locally called kuwat malakamay or

kuwat malakamawey by sub-tribes Mag-Indi

(Pampanga) and Zambal (Zambales) (Table 4).

This naming of mushrooms by the Aeta

communities was based on the substrates

where the mushrooms were actually found.

Similarly, the Igala people of Nigera named

mushrooms according to its features and the

substrates where they are found (Ayodele et al.

2011). In our study, Lentinus sajor-caju is

known as kuwat kawayan since it is found

growing in bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris). In the

Philippines, kawayan is the local name for

this species of bamboo. At this time we cannot

say the number of mushrooms utilized by the

Aeta communities until specimens for the

locally given names are all collected and

accounted for, which may take several years.

However, our study provides baseline

information on the species of mushrooms

utilized by the Aeta tribes.

256

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

Table 4 Similarities in local names of collected mushrooms utilized by the six Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Northern, Philippines

Different Aeta Sub-Tribes

Mag-Indi

Mag-Antsi

Auricularia auricular

Kuwat Malabalugbug dagis/Kuwat Kuling baki

Kuwat Malabalugbug dagis

Auricularia polytricha

Kuwat Tikbakulaw

Kuwat Malabalugbug dagis

Calvatia sp.

Kuwat Bola/Kuwat Duldul

Ganoderma lucidum

Pleurotus sp.

Lentinus tigrinus

Kuwat Miyapol

Lentinus sajor-caju

Mycena sp.

Kuwat Anglap/Kuwat Papait

Schizophyllum commune

Kuwat Kuritdit

Termitomyces clypeatus

Kuwat Uong/Kuwat Lupa

Kuwat Kuyog

Termitomyces robustus

Kuwat Malakamay

Termitomyces sp. 1

Kuwat Mayo

Kuwat Mayo

Termitomyces sp. 2

Kuwat Malakamay

Volvariella volvacea

Kuwat Saging

Kuwat Amucao

Negative (-) means not utilized by the specific Aeta sub- tribes.

Scientific Name

Zambal

Kuwat Tangkiki

Kuwat Tangkiki

Kuwat Kahoy

Kuwat Kasoy

Kuwat Kikitban

Kuwat Kawayan

Kuwat Hanggilit

Kuwat Gilatgilatan

Kuwat Malakamawey

Kuwat Mayo/Kuwat Yabot

Kuwat Malakamawey

Kuwat Amucao

Table 5 Mushrooms utilized by the six Aeta communities in Central Luzon, Northern Philippines.

Mushroom

Sub-tribe Mag-Indi

Mawacat (AD)

Nabuclod (RA)

Sub-tribe Mag-Antsi

Yeyoung (AD)

Kalangitan (RA)

Sub-tribe Zambal

Bucao (AD)

Bihawo (RA)

As Food

Auricularia auricular

Auricularia polytricha

Calvatia sp.

Lentinus tigrinus

Lentinus sajor-caju

Pleurotus sp.

Schizophyllum commune

Termitomyces clypeatus

Termitomyces robustus

Termitomyces sp. 1

Termitomyces sp. 2

Volvariella volvacea

As Medicine

Mycena sp.

As Decoration

Ganoderma lucidum

+ = utilized by the Aeta sub-tribes

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

- = not utilized by the Aeta sub-tribes

257

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

The number of species utilized by

different Aeta tribes varies in relation to their

residential sites (Table 5). It is interesting to

note that the mushrooms utilized by the Aeta

communities in their ancestral domains were

also utilized by the sub-tribes who now live in

the resettlement areas. This shows that the subtribes that resettled in different communities

other than their ancestral domains still observe

their customs and beliefs on mushrooms and

utilized the same species of mushrooms they

once used in their ancestral homes. Their

utilization of these species remained the same.

For example, T. clypeatus was used as food by

all three sub-tribes living in their ancestral

domains. The same species were also used as

food by other sub-tribes presently living in the

resettlement areas.

Indigenous

Beliefs

on

Mushroom

Cultivation and Utilization

The different Aeta sub-tribes are also

governed by different indigenous beliefs when

it comes to mushroom collection, utilization,

and cultivation. Some of their indigenous

knowledge was as follows:

(1) They do not cook mushrooms together with

yellow or red vegetables or with shrimps, fish,

and snails as eating these cooked food could

cause fatal sickness.

(2) One large mushroom species identified

only as belonging to the genus Termitomyces is

believed to be guarded by supernatural beings.

Thus, before collecting this mushroom, subtribe Mag-Indi performs dancing rituals or asks

permission from the spirits and kisses the

ground.

(3) Sub-tribe Zambal simply thanks their local

deity Apo Namalyari for the abundance of

their collected mushrooms.

(4) Sub-tribe Mag-Antsi in Tarlac forbids

combing their hair and singing while cooking

mushrooms. They believed this could attract

lightning to strike the person.

(5) Sub-tribe Zambal also mentioned that they

should not observe the development of

mushrooms on the ground as the mushroom

will not continue to grow.

(6) Interestingly, all Aeta sub-tribes believed

that spontaneous lightning causes the growth of

mushrooms. Such a belief was also known in

Japanese farming folklore (Ryall, 2010). In

fact, researchers in northern Japan bombarded

a variety of mushrooms in lab-based garden

plots with artificially induced lightning to see if

electricity actually makes the fungi multiply

(Ryall, 2010).

(7) The Aeta sub-tribes also believed that

mushrooms grow where the water used to wash

or clean mushrooms was thrown. This is

expected since mushroom spores present in the

washed water would germinate and form

fruiting bodies.

In summary, 38 macrofungi were

recorded by the six Aeta sub-tribes in

Pampanga, Tarlac and Zambales. Only 14

species of these reported mushrooms were

collected and identified. The Aeta sub-tribes

used these mushrooms as food, as medicine or

as household decoration.

Interestingly, the Aetas used similar

common names for different species of

mushrooms since naming of the species was

based on their substrates. All sub-tribes used

the same species of mushrooms when living in

their ancestral homes or in resettlement areas.

Our study highlighted the importance of

enthnomycological studies in preserving the

indigenous knowledge of our indigenous

people.

Acknowledgements

This research project is supported by a

dissertation grant given by the Commission on

Higher Education (CHED), Republic of the

Philippines. The authors thank Dr. Cristina

Binag, Research Center for Natural and

Applied Sciences, UST and Dr. Sofronio

Kalaw, Center for Tropical Mushroom

Research and Development, CLSU for their

assistance in the conduct of this study. We also

thank Mr. Sallong Sunggod and the staff of the

National Commission on Indigenous People

(NCIP) for their assistance during the field

collection.

References

Ayodele SM, Akpaja EO, Adamu Y 2011 Some edible and medicinal mushrooms

of Igala Land in Nigeria, their

sociocultural and ethnomycological

258

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/2/9

uses. International Journal of Science

and Nature 2, 473476.

Cabauatan JG 2008 - Ethnobotanical

investigations among the five ethnic

groups in the Northern Cagayan Valley.

Dissertation University of Santo

Tomas, Manila, Graduate School.

Cario JK 2010 - Country Technical Notes on

Indigenous Peoples Issues Philippines.

International Fund for Agricultural

Development (IFAD). www.ifad.org.ph

Christensen M, Larsen HO 2005 - How can

collection of wild edible fungi

contribute to livelihoods in rural areas

of Nepal? Journal of Forest and

Livelihood 4, 5055.

GaribayOrijel R, Cifuentes J, EstradaTorres

A, Caballero J 2006 - People using

macrofungal diversity in Oaxaca,

Mexico. Fungal Diversity 21, 4167.

Henkel TW, Aime MC, Chin M, Andrew C

2004 - Edible mushrooms from

Guyana. Mycologist 18, 104111.

Labarere J, Gemini U 2000 - Collection,

characterization, conservation and

utilization of mushrooms germplasm

resources in Africa. The Global

Network on Mushrooms. FAO. 1734.

Lodge DJ, Ammiranti JF, Odell TE, Mueller

GM 2004 - Collecting and describing

macrofungi. In: Biodiversity of Fungi:

Inventory and Monitoring Methods (eds

GM Mueller, GF Bills, MS Foster).

Elsevier Academic Press, USA, 128158.

Montoya A, Kong A, Estrada-Torres A,

Cifuentes J, Caballero J 2004 - Useful

wild fungi of La Malinche National

Park, Mexico. Fungal Diversity 17,

115143.

National Commision on Indigenous People

(NCIP) 2009 - List of Indigenous

Peoples

in

the

Philippines.

http://www.ncip.gov.ph/

Pegler DN, Pierce GD 1980 - The edible

mushrooms of Zambia. Kew Bulletin

35, 475491.

Quimio TH 2001 - Workbook on Tropical

Fungi: Collection, Isolation and

Identification. The Mycological Society

of the Philippines, Inc., Laguna

Rammeloo J, Walleyn R 1993 - The edible

fungi of Africa south of the Sahara.

Scripta Botanica Belgica 5, 162.

Reyes RG, Abella EA, Quimio TH 2003 - Wild

macrofungi of CLSU. Journal of

Tropical Biology 2, 811.

Ryall J 2012 - National Geographic News.

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/ne

ws/2010/04/100409-lightningmushrooms-japan-harvest/

Sheldrick WS 1990 - Mycenon, a new

metabolite from a Mycena species TA

87202 (basidiomycetes) as an inhibitor

of isocitrate lyase. The Journal of

Antibiotics 43, 12401244.

Shimizu H 1989 Pinatubo Aytas: Continuity

and Change. Manila: Ateneo de Manila

Press., pp. 3140.

Sillitoe P 1995 - An ethnobotanical account of

the plant resources of the Wola Region,

Southern Highlands Province, Papua

New Guinea, Journal of Ethnobiology

15, 201235.

Tayamen MJ, Reyes RG, Floresca EJ, Abella

EA 2004 - Domestication of wild edible

mushrooms as non-timber forest

products resources among the Aetas of

Mt.

Nagpale,

Abucay,

Bataan:

Ganoderma sp. and Auricularia

polytricha. The Journal of Tropical

Biology 3, 4951.

United Nations Development Programme

(UNDP) 2010 - Indigenous Peoples in

the

Philippines:

Fast

Facts.

www.undp.org.ph

Waddington R 2002 - The Aeta. Retrieved

September 1, 2010, from The Peoples

of

the

World

Foundation.

http://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?

people=Aeta

Yongabi K, Agho M, Carrera DM 2004 Ethnomycological studies on wild

mushrooms in Cameroon, Central

Africa. Micologia Aplicada International 16(2), 3436.

259

You might also like

- Modern Crises and Traditional Strategies: Local Ecological Knowledge in Island Southeast AsiaFrom EverandModern Crises and Traditional Strategies: Local Ecological Knowledge in Island Southeast AsiaNo ratings yet

- An Ethnomycological Survey of Macrofungi Utilized by Aeta Communities in Central Luzon, PhilippinesDocument9 pagesAn Ethnomycological Survey of Macrofungi Utilized by Aeta Communities in Central Luzon, PhilippinesKring Kring K. KringersNo ratings yet

- Mobility and Migration in Indigenous Amazonia: Contemporary Ethnoecological PerspectivesFrom EverandMobility and Migration in Indigenous Amazonia: Contemporary Ethnoecological PerspectivesMiguel N. AlexiadesNo ratings yet

- Ethnopharmacologic Documentation ofDocument56 pagesEthnopharmacologic Documentation ofchen de limaNo ratings yet

- Centralizing Fieldwork: Critical Perspectives from Primatology, Biological and Social AnthropologyFrom EverandCentralizing Fieldwork: Critical Perspectives from Primatology, Biological and Social AnthropologyNo ratings yet

- Ethnomycological Survey of The Kalanguya Indigenous Community in Caranglan, Nueva Ecija, PhilippinesDocument6 pagesEthnomycological Survey of The Kalanguya Indigenous Community in Caranglan, Nueva Ecija, PhilippinesMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Amphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean Slope: A Comprehensive GuideFrom EverandAmphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean Slope: A Comprehensive GuideRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Traditional Forest Conservation Knowledge Technologies in The CordilleraDocument6 pagesTraditional Forest Conservation Knowledge Technologies in The CordilleraKatrina SantosNo ratings yet

- An Ethnomycological Survey of Macrofungi Utilized by Dumagat Community in Dingalan, AuroraDocument9 pagesAn Ethnomycological Survey of Macrofungi Utilized by Dumagat Community in Dingalan, AuroraIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Diversity and Community Structure of Basidiomycetes in Alimodian Draaaaaftiloilo Philippines Draft 1Document32 pagesDiversity and Community Structure of Basidiomycetes in Alimodian Draaaaaftiloilo Philippines Draft 1miali anasNo ratings yet

- Useful Plants of Selected Ayta Communiti PDFDocument22 pagesUseful Plants of Selected Ayta Communiti PDFGlenn Frey LayugNo ratings yet

- Species Diversity of Odonata in Bolyok Falls, Naawan, Misamis Oriental, PhilippinesDocument8 pagesSpecies Diversity of Odonata in Bolyok Falls, Naawan, Misamis Oriental, PhilippinesKristal Cay AragonNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotanical Studyof Some Useful FloraDocument16 pagesEthnobotanical Studyof Some Useful FloraMary Joy Salim ParayrayNo ratings yet

- INDIGENOUS STRATEGIESDocument6 pagesINDIGENOUS STRATEGIESRhadzma JebulanNo ratings yet

- Philippine Indigenous People The AetasDocument3 pagesPhilippine Indigenous People The Aetasahmad earlNo ratings yet

- Persepsi Masyarakat Tentang Manfaat Budaya Dan Kesehatan Mengonsumsi Tambelo, Siput Dan Kerang Di Mimika, PapuaDocument10 pagesPersepsi Masyarakat Tentang Manfaat Budaya Dan Kesehatan Mengonsumsi Tambelo, Siput Dan Kerang Di Mimika, PapuarasajangkrikNo ratings yet

- Mindoro Mangyan EthnobotanyDocument17 pagesMindoro Mangyan EthnobotanyAgatha AgatonNo ratings yet

- Rubiaceae Flore of Northern Sierra MadreDocument15 pagesRubiaceae Flore of Northern Sierra MadreRachel BiagNo ratings yet

- Plants and Culture: Plant Utilization Among The Local Communities in Kabayan, Benguet Province, PhilippinesDocument14 pagesPlants and Culture: Plant Utilization Among The Local Communities in Kabayan, Benguet Province, PhilippinesHyenaNo ratings yet

- Final Outline (Charming Sotelo) PDFDocument19 pagesFinal Outline (Charming Sotelo) PDFjcNo ratings yet

- Barreau Et Al 2016Document22 pagesBarreau Et Al 2016Felice WyndhamNo ratings yet

- H L P L B (V T, C, A) : M. Flamini Et Al. - Hongos Útiles y Tóxicos Según Los Yuyeros de La Paz y Loma BolaDocument20 pagesH L P L B (V T, C, A) : M. Flamini Et Al. - Hongos Útiles y Tóxicos Según Los Yuyeros de La Paz y Loma BolaGuilleGardenalNo ratings yet

- Ethnomedicinal Plants of SantolDocument23 pagesEthnomedicinal Plants of SantoldssgssNo ratings yet

- Population Size and Dynamics of The Lima Leaf-Toed Gecko, Phyllodactylus Sentosus, in One of Its Last RefugesDocument7 pagesPopulation Size and Dynamics of The Lima Leaf-Toed Gecko, Phyllodactylus Sentosus, in One of Its Last RefugesMaricielo Dayane Celiz ParilloNo ratings yet

- Species Distribution and Relative Abundace of Land Snails in Mt. MusuanMaramag Bukidnon.Document14 pagesSpecies Distribution and Relative Abundace of Land Snails in Mt. MusuanMaramag Bukidnon.Fatimae Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- ToothacheDocument8 pagesToothacheApril Joy de LimaNo ratings yet

- Jenis Dan Jumlah Konsumsi Tambelo, Siput Dan Kerang Oleh Penduduk Di Kawasan Muara Mimika, PapuaDocument12 pagesJenis Dan Jumlah Konsumsi Tambelo, Siput Dan Kerang Oleh Penduduk Di Kawasan Muara Mimika, PapuarasajangkrikNo ratings yet

- Species Diversity and Spatial Structure of Intertidal Mollusks in Padada, Davao Del Sur, PhilippinesDocument10 pagesSpecies Diversity and Spatial Structure of Intertidal Mollusks in Padada, Davao Del Sur, PhilippinesCharlie Magne H. DonggonNo ratings yet

- Final Report of Ata-Manobo DavaoDocument74 pagesFinal Report of Ata-Manobo DavaoJyrhelle Laye SalacNo ratings yet

- An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants of Chungtia VillageDocument13 pagesAn Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants of Chungtia VillageNur FitriantoNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotanical Investigation of Three Traditional Leafy Vegetables (Alternanthera Sessilis (L.) DC. Bidens Pilosa L. Launaea Taraxacifolia Willd.) Widely Consumed in Southern and Central BeninDocument12 pagesEthnobotanical Investigation of Three Traditional Leafy Vegetables (Alternanthera Sessilis (L.) DC. Bidens Pilosa L. Launaea Taraxacifolia Willd.) Widely Consumed in Southern and Central BeninInternational Network For Natural SciencesNo ratings yet

- Comparative Species Composition and Relative Abundance of Mollusca in Marine Habitat of Sinunuk Island, Zamboanga CityDocument4 pagesComparative Species Composition and Relative Abundance of Mollusca in Marine Habitat of Sinunuk Island, Zamboanga CityFerhaeeza KalayakanNo ratings yet

- The Macrofungi in The Island of San Antonio, Northern Samar, PhilippinesDocument8 pagesThe Macrofungi in The Island of San Antonio, Northern Samar, PhilippinesEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Indigenous Aetas of Bataan, Philippines: Extraordinary Genetic Origins, Modern History and Land RightsDocument15 pagesThe Indigenous Aetas of Bataan, Philippines: Extraordinary Genetic Origins, Modern History and Land RightsVince Sabala BalillaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No.1Document4 pagesAssignment No.1Gerald GamboaNo ratings yet

- Underutilized Plant Resources in Tinoc, Ifugao, Cordillera Administrative Region, Luzon Island, PhilippinesDocument15 pagesUnderutilized Plant Resources in Tinoc, Ifugao, Cordillera Administrative Region, Luzon Island, Philippinespepito manalotoNo ratings yet

- Biology and Conservation of The Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of PeruDocument14 pagesBiology and Conservation of The Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of PeruGeorge A. LoayzaNo ratings yet

- Detecting GM Soybean with Multiplex PCRDocument50 pagesDetecting GM Soybean with Multiplex PCRLenny Mae JagosNo ratings yet

- 7.5.2.2 Final Report of Dumagat AuroraDocument127 pages7.5.2.2 Final Report of Dumagat AuroraAlvin HalconNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Plants Among The Indigenous People of Lidlidda, Ilocos SurDocument24 pagesEthnobotanical Knowledge of Plants Among The Indigenous People of Lidlidda, Ilocos SurNico MorilloNo ratings yet

- Research Article Protozoan Parasites in Group-Living Primates: Testing The Biological Island HypothesisDocument8 pagesResearch Article Protozoan Parasites in Group-Living Primates: Testing The Biological Island Hypothesisapi-527444510No ratings yet

- Healthcare Practices of Yapayao - Isneg Tribe An Ethnographic Study in Contemporary WorldDocument10 pagesHealthcare Practices of Yapayao - Isneg Tribe An Ethnographic Study in Contemporary WorldIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Gilbert C. Magulod JR., PH.D., Janilete R. Cortez, Maed, Bernard P. Madarang, MaedDocument7 pagesGilbert C. Magulod JR., PH.D., Janilete R. Cortez, Maed, Bernard P. Madarang, MaedRodel UrianNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotanical Documentation of Medicinal Plants Used by The Indigenous Panay Bukidnon in Lambunao, Iloilo, PhilippinesDocument20 pagesEthnobotanical Documentation of Medicinal Plants Used by The Indigenous Panay Bukidnon in Lambunao, Iloilo, PhilippinesLucienne IhaladNo ratings yet

- 3.paper Philippines Feb23++++LatestDocument15 pages3.paper Philippines Feb23++++LatestcnightNo ratings yet

- Report Ayta TayabasDocument73 pagesReport Ayta TayabasAnonymous DcQJTQpw100% (1)

- Ijsrp p10498Document7 pagesIjsrp p10498fretchie chatoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Ethnobiology and EthnomedicineDocument13 pagesJournal of Ethnobiology and EthnomedicinelatitecilouNo ratings yet

- Rediscovering Philippine Psychotria SpeciesDocument11 pagesRediscovering Philippine Psychotria SpeciesRachel BiagNo ratings yet

- Plants Species in The Folk Medicine of Montecorvino Rovella - CampaniaDocument9 pagesPlants Species in The Folk Medicine of Montecorvino Rovella - CampaniaItay Raphael OronNo ratings yet

- Ethnofarming Practices of Indigenous Subanen and Mansaka GroupsDocument4 pagesEthnofarming Practices of Indigenous Subanen and Mansaka GroupsPaul Omar PastranoNo ratings yet

- Ijtk 10 (2) 227-238 PDFDocument12 pagesIjtk 10 (2) 227-238 PDFCeline Jane DiazNo ratings yet

- Advances in Environmental BiologyDocument12 pagesAdvances in Environmental BiologyDavid ChristiantoNo ratings yet

- Diet and parasite analysis of invasive frog species in Butuan CityDocument29 pagesDiet and parasite analysis of invasive frog species in Butuan CityJulian Valmorida Torralba IINo ratings yet

- Corrigan Et. Al South African Journal of Botany 77 (2011) 346-359Document14 pagesCorrigan Et. Al South African Journal of Botany 77 (2011) 346-359Sebastian Orjuela ForeroNo ratings yet

- VertebratesDocument13 pagesVertebratesMeshiela TorresNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotanical Important Plants Among THDocument12 pagesEthnobotanical Important Plants Among THJohn VillalbaNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument64 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundJustine RosarioNo ratings yet

- Terrestrial Bdv Mini Thesis (Fauna)Document26 pagesTerrestrial Bdv Mini Thesis (Fauna)Iriesh Nichole BaricuatroNo ratings yet

- Fern Literature PDFDocument15 pagesFern Literature PDFDennis Nabor Muñoz, RN,RM100% (1)

- Architect Boardprogram June2019 0Document2 pagesArchitect Boardprogram June2019 0Marlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- An Inventory of Studies on Good Urban Governance and Security of TenureDocument14 pagesAn Inventory of Studies on Good Urban Governance and Security of TenureMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- SHEC Empowers Pasay's Urban PoorDocument2 pagesSHEC Empowers Pasay's Urban PoorMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2. URBAN ECONOMY: The Ecological Economics of Sustainable Ekistic Formation in The PhilippinesDocument36 pagesChapter 2. URBAN ECONOMY: The Ecological Economics of Sustainable Ekistic Formation in The PhilippinesMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Ground Floor Plan: A B C D EDocument1 pageGround Floor Plan: A B C D EMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- ErterDocument2 pagesErterMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Crime Prevention Through Environmental DesignDocument28 pagesCrime Prevention Through Environmental DesignMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- DFGDFGDFDocument3 pagesDFGDFGDFMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- WrewerDocument1 pageWrewerMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- 6456456Document42 pages6456456Marlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- RyryrtyrtDocument13 pagesRyryrtyrtMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- V-Ray Settings Overview: Alex Hogrefe Fundamentals 54 CommentsDocument16 pagesV-Ray Settings Overview: Alex Hogrefe Fundamentals 54 CommentsMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Guindulman LivestockDispersalDocument5 pagesGuindulman LivestockDispersalAl SimbajonNo ratings yet

- WrewerDocument1 pageWrewerMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- ErtertetertDocument1 pageErtertetertMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Celebrating Life's Simple JoysDocument1 pageCelebrating Life's Simple JoysMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- HTTPDocument39 pagesHTTPMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- WerwerwDocument26 pagesWerwerwMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Philippines IndonesiaDocument44 pagesPhilippines IndonesiaMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- DepEd Order No. 49 S. 2006Document9 pagesDepEd Order No. 49 S. 2006julandmic9100% (30)

- RA 9513 - Renewable Energy Act PresentationDocument49 pagesRA 9513 - Renewable Energy Act PresentationEstudyante BluesNo ratings yet

- ErterterDocument261 pagesErterterMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- $eating The Interview ProtocolDocument9 pages$eating The Interview ProtocolasmaNo ratings yet

- 242 Assignment 1 Interview ProtocolDocument6 pages242 Assignment 1 Interview ProtocolMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Atty. Ronaldo M. Daquioag Region III Director National Commission On Indigenous PeopleDocument22 pagesAtty. Ronaldo M. Daquioag Region III Director National Commission On Indigenous PeopleMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Ipra IrrDocument58 pagesIpra IrrMac Manuel100% (1)

- History: Indigenous People Luzon Philippines NegritosDocument7 pagesHistory: Indigenous People Luzon Philippines NegritosKaren Mae AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Household Profile Questionnaire: Community-Based Monitoring SystemDocument12 pagesHousehold Profile Questionnaire: Community-Based Monitoring SystemMarlo Anthony BurgosNo ratings yet

- Friends with Mammon: An exegetical study of Luke 16v1-9 (Part 1Document21 pagesFriends with Mammon: An exegetical study of Luke 16v1-9 (Part 1Ryan TinettiNo ratings yet

- Articulating Rapa Nui - Riet DelsingDocument25 pagesArticulating Rapa Nui - Riet Delsingamatisa100% (2)

- 10 Historical Persian Queens and EmpressesDocument5 pages10 Historical Persian Queens and Empressesmehedi2636No ratings yet

- Mosaic TRD1 Tests U1 3Document3 pagesMosaic TRD1 Tests U1 3Mary StevensNo ratings yet

- Britain and Ireland 900 - 1300Document301 pagesBritain and Ireland 900 - 1300Ricardo Sá Ferreira100% (3)

- Customs of The TagalogsDocument4 pagesCustoms of The TagalogsMaria PotpotNo ratings yet

- Data Siswa Prakerin 2022-2023Document10 pagesData Siswa Prakerin 2022-2023Tulus 6455No ratings yet

- Rosary Novena To Our Lady of La NavalDocument2 pagesRosary Novena To Our Lady of La NavalCedrick Cochingco Sagun100% (4)

- The Twilight Saga SoundtrackDocument5 pagesThe Twilight Saga SoundtrackNadia Reneesme MartinezNo ratings yet

- The Awakening Call to the End-time RemnantDocument2 pagesThe Awakening Call to the End-time Remnantpastorrlc8852No ratings yet

- Anton DiabelliDocument1 pageAnton DiabelliGeorge PikNo ratings yet

- English Translation of Nasihatu-Khairil-Anaam-Li-As-Haabihil-Kiraam-Part-IiDocument33 pagesEnglish Translation of Nasihatu-Khairil-Anaam-Li-As-Haabihil-Kiraam-Part-IitakwaniaNo ratings yet

- Djypsy Djazz Djam BookDocument234 pagesDjypsy Djazz Djam BookAntoniousBlock100% (3)

- Newmemb Web (ICNC 123)Document45 pagesNewmemb Web (ICNC 123)Bandaru Sai BabuNo ratings yet

- Angelus Prayer Against Terror and ViolenceDocument1 pageAngelus Prayer Against Terror and ViolenceRah-rah Tabotabo ÜNo ratings yet

- Absensi PIN KalapasawitDocument22 pagesAbsensi PIN KalapasawitSiska Widi utamiNo ratings yet

- Verval Peserta DidikDocument24 pagesVerval Peserta Didiksyahruddin asqlanyNo ratings yet

- Using The Last Crescent To Anticipate ConjunctionDocument5 pagesUsing The Last Crescent To Anticipate Conjunctionscuggers1No ratings yet

- Phil Pre-Colonial Art by ORIGENESDocument7 pagesPhil Pre-Colonial Art by ORIGENESDominique OrigenesNo ratings yet

- Result A DosDocument10 pagesResult A DosRoyer Quispe BejarNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled DocumentSanjit DashNo ratings yet

- ADMISSION REGISTER TITLEDocument61 pagesADMISSION REGISTER TITLESARAVANAN SELVARAJNo ratings yet

- Job Prologue Without Notes (David J A Clines Translation)Document1 pageJob Prologue Without Notes (David J A Clines Translation)eustoque2668No ratings yet

- People and RelationshipsDocument4 pagesPeople and RelationshipsMašaTihelNo ratings yet

- Political Science Project Name:Aarushi Class:Xii-F Roll No:1 Topic:Integration of Princely States (Hyderabad and Manipur)Document13 pagesPolitical Science Project Name:Aarushi Class:Xii-F Roll No:1 Topic:Integration of Princely States (Hyderabad and Manipur)johriaarushiNo ratings yet

- SayingsDocument32 pagesSayingsNsereko IvanNo ratings yet

- Youth - Search - The - Scriptures - Volume 67 PDFDocument38 pagesYouth - Search - The - Scriptures - Volume 67 PDFAlpha100% (1)

- Journal of American Folklore (18 & 19) (1906)Document726 pagesJournal of American Folklore (18 & 19) (1906)Mikael de SanLeon100% (5)

- Your Erroneous Zones - Wayne Dyer (Full Ebook)Document131 pagesYour Erroneous Zones - Wayne Dyer (Full Ebook)Mohsin Hassan87% (55)

- Raipur District Panchayat Education Department Merit List for Subject HindiDocument1,392 pagesRaipur District Panchayat Education Department Merit List for Subject HindiSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Tales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceFrom EverandTales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (18)

- All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesFrom EverandAll That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (397)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondFrom EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the MindFrom EverandThe Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (93)

- Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveFrom EverandGood Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (66)

- This Is Your Brain On Parasites: How Tiny Creatures Manipulate Our Behavior and Shape SocietyFrom EverandThis Is Your Brain On Parasites: How Tiny Creatures Manipulate Our Behavior and Shape SocietyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (31)

- 10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessFrom Everand10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (33)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsFrom EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Who's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainFrom EverandWho's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (65)

- The Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorFrom EverandThe Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorNo ratings yet

- The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildFrom EverandThe Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedFrom EverandUndeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Human: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueFrom EverandHuman: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (38)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldFrom EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Second Brain: A Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and IntestineFrom EverandThe Second Brain: A Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and IntestineRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Superlative: The Biology of ExtremesFrom EverandSuperlative: The Biology of ExtremesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (51)

- Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomFrom EverandBuddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (215)

- Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious FishFrom EverandEels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious FishRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (30)

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceFrom EverandThe Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (515)

- Human Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, from Pointless Bones to Broken GenesFrom EverandHuman Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, from Pointless Bones to Broken GenesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (56)

- Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meaning of LifeFrom EverandDarwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meaning of LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (523)

- The Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental ForceFrom EverandThe Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental ForceNo ratings yet

- The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human IntelligenceFrom EverandThe Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human IntelligenceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (632)