Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Neri Vs Senate Case Digest

Uploaded by

Aaron TanyagOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Neri Vs Senate Case Digest

Uploaded by

Aaron TanyagCopyright:

Available Formats

NERI VS.

SENATE COMMITTEE

ROMULO L. NERI, petitioner vs. SENATE COMMITTEE ON

ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS AND

INVESTIGATIONS, SENATE COMMITTEE ON TRADE AND

COMMERCE, AND SENATE COMMITTEE ON NATIONAL

DEFENSE AND SECURITY

G.R. No. 180643, March 25, 2008

FACTS: On April 21, 2007, the Department of Transportation and

Communication (DOTC) entered into a contract with Zhong Xing

Telecommunications Equipment (ZTE) for the supply of equipment

and services for the National Broadband Network (NBN) Project in

the amount of U.S. $ 329,481,290 (approximately P16 Billion Pesos).

The Project was to be financed by the Peoples Republic of China.

The Senate passed various resolutions relative to the NBN deal. In

the September 18, 2007 hearing Jose de Venecia III testified that

several high executive officials and power brokers were using their

influence to push the approval of the NBN Project by the NEDA.

Neri, the head of NEDA, was then invited to testify before the Senate

Blue Ribbon. He appeared in one hearing wherein he was

interrogated for 11 hrs and during which he admitted that Abalos of

COMELEC tried to bribe him with P200M in exchange for his approval

of the NBN project. He further narrated that he informed President

Arroyo about the bribery attempt and that she instructed him not to

accept the bribe.

However, when probed further on what they discussed about the

NBN Project, petitioner refused to answer, invoking executive

privilege. In particular, he refused to answer the questions on:

(a) whether or not President Arroyo followed up the NBN Project,

(b) whether or not she directed him to prioritize it, and

(c) whether or not she directed him to approve.

He later refused to attend the other hearings and Ermita sent a

letter to the senate averring that the communications between GMA

and Neri are privileged and that the jurisprudence laid down in

Senate vs Ermita be applied. He was cited in contempt of

respondent committees and an order for his arrest and detention

until such time that he would appear and give his testimony.

ISSUE:

Are the communications elicited by the subject three (3) questions

covered by executive privilege?

HELD:

The communications are covered by executive privilege

The revocation of EO 464 (advised executive officials and employees

to follow and abide by the Constitution, existing laws and

jurisprudence, including, among others, the case of Senate v. Ermita

when they are invited to legislative inquiries in aid of legislation.),

does not in any way diminish the concept of executive privilege. This

is because this concept has Constitutional underpinnings.

The claim of executive privilege is highly recognized in cases where

the subject of inquiry relates to a power textually committed by the

Constitution to the President, such as the area of military and

foreign relations. Under our Constitution, the President is the

repository of the commander-in-chief, appointing, pardoning, and

diplomatic powers. Consistent with the doctrine of separation of

powers, the information relating to these powers may enjoy greater

confidentiality than others.

Several jurisprudence cited provide the elements of presidential

communications privilege:

1) The protected communication must relate to a quintessential

and non-delegable presidential power.

2) The communication must be authored or solicited and received

by a close advisor of the President or the President himself. The

judicial test is that an advisor must be in operational proximity

with the President.

3) The presidential communications privilege remains a qualified

privilege that may be overcome by a showing of adequate need,

such that the information sought likely contains important

evidence and by the unavailability of the information elsewhere by

an appropriate investigating authority.

In the case at bar, Executive Secretary Ermita premised his claim of

executive privilege on the ground that the communications elicited

by the three (3) questions fall under conversation and

correspondence between the President and public officials

necessary in her executive and policy decision-making process

and, that the information sought to be disclosed might impair our

diplomatic as well as economic relations with the Peoples Republic

of China. Simply put, the bases are presidential communications

privilege and executive privilege on matters relating to diplomacy or

foreign relations.

Using the above elements, we are convinced that, indeed, the

communications elicited by the three (3) questions are covered by

the presidential communications privilege. First, the communications

relate to a quintessential and non-delegable power of the

President, i.e. the power to enter into an executive agreement with

other countries. This authority of the President to enter into

executive agreements without the concurrence of the Legislature

has traditionally been recognized in Philippine jurisprudence.

Second, the communications are received by a close advisor of the

President. Under the operational proximity test, petitioner can be

considered a close advisor, being a member of President Arroyos

cabinet. And third, there is no adequate showing of a compelling

need that would justify the limitation of the privilege and of the

unavailability of the information elsewhere by an appropriate

investigating authority.

Respondent Committees further contend that the grant of

petitioners claim of executive privilege violates the constitutional

provisions on the right of the people to information on matters of

public concern.50 We might have agreed with such contention if

petitioner did not appear before them at all. But petitioner made

himself available to them during the September 26 hearing, where

he was questioned for eleven (11) hours. Not only that, he expressly

manifested his willingness to answer more questions from the

Senators, with the exception only of those covered by his claim of

executive privilege.

The right to public information, like any other right, is subject to

limitation. Section 7 of Article III provides:

The right of the people to information on matters of public concern

shall be recognized. Access to official records, and to documents,

and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions, or decisions, as

well as to government research data used as basis for policy

development, shall be afforded the citizen, subject to such

limitations as may be provided by law.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elasticity and Its ApplicationDocument55 pagesElasticity and Its ApplicationAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Transcultural CitiesDocument14 pagesTranscultural CitiesAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Forgetting Informal Spaces ManilaDocument17 pagesForgetting Informal Spaces ManilaAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Excel Shortcuts 2003: Editing: General NavigationDocument2 pagesExcel Shortcuts 2003: Editing: General NavigationAnyanele Nnamdi FelixNo ratings yet

- IPRA-Isagani Cruz Vs DENRDocument10 pagesIPRA-Isagani Cruz Vs DENRJa-mes BF100% (1)

- Weekend HomeworkDocument2 pagesWeekend HomeworkAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

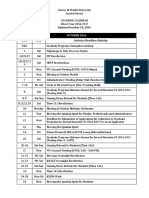

- SY 2016-2017 Academic Calendar V5 24oct2016Document11 pagesSY 2016-2017 Academic Calendar V5 24oct2016Aaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Weekend HomeworkDocument2 pagesWeekend HomeworkAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Peter PiperDocument1 pagePeter PiperAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Making and Breaking Commitments: A Look at Interpersonal RelationshipsDocument78 pagesMaking and Breaking Commitments: A Look at Interpersonal RelationshipsAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- English ReviewerDocument10 pagesEnglish ReviewerAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- 13 40 Smartphone Overuse Growing and Harmful To AdolescentsDocument1 page13 40 Smartphone Overuse Growing and Harmful To AdolescentsAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- AP ReviewerDocument16 pagesAP ReviewerAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Theo OralsDocument8 pagesReviewer Theo OralsAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- AP ReviewerDocument16 pagesAP ReviewerAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Histo Italy - EDITEDDocument4 pagesHisto Italy - EDITEDAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Keeping The Faith in Times of Suffering Interview of Richard Leonard 2Document7 pagesKeeping The Faith in Times of Suffering Interview of Richard Leonard 2Aaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- Lit 13 StoryDocument20 pagesLit 13 StoryAaron TanyagNo ratings yet

- BHS TestingProject201311Document4 pagesBHS TestingProject201311Aaron TanyagNo ratings yet