Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4&5 IssuePaper PDF

Uploaded by

yilikal addisu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views5 pagesOriginal Title

4&5_IssuePaper.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views5 pages4&5 IssuePaper PDF

Uploaded by

yilikal addisuCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Building Environmental Assessment Tools: Current and Future Roles

Raymond J Cole and Nigel Howard

Toshiharu Ikaga and Sylviane Nibel

Until the 1990 release of the Building Research Establishment Environmental

Assessment Method - BREEAM, little, if any, attempt had been made to establish an

objective and comprehensive means of simultaneously assessing a broad range of

environmental considerations against explicitly declared criteria, and offering a

summary of overall performance. Moreover and often controversially, to do so in a

way that motivates change in the construction industry and market transformation by

attaching a label of environmental performance that increases the real market value of

buildings with improved environmental qualities. The field of building environmental

assessment has matured remarkably quickly since the introduction of BREEAM, and

the past thirteen years have witnessed a rapid increase in the number of building

environmental assessment methods in use world-wide (e.g. BREEAM UK; LEED

US, TGBRS India; CASBEE Japan; NABERS, Australia, etc.)

Initially, the development of building environmental assessment methods was largely

an exercise in structuring a broad range of existing knowledge and considerations into

a practical framework, rather than requiring or demanding new research. All of the

major international conferences since 1994 have allocated a significant portion of their

programs to the description and comparison of these methods and assessment now

represents a central focus for the building environmental design and performance

debate. Now building environmental assessment is a defined realm of enquiry with

more rigorous explorations into weighting protocols, performance indicators,

effectiveness market and physical etc. At SB05, we want to reflect on the continuing

evolution of building environmental assessment by asking the question what are

their current and future roles?

The emergence and evolution of building environmental assessments responds to a

tension between the desire for objective, scientifically rigorous and stringent

performance criteria with the desire for practical, transparent, simple to understand

criteria that ask the industry to respond to manageable step changes in practice.

Building environmental assessment methods were conceived as being voluntary and

motivational in their application and their current success (both in terms of the amount

of total new construction floor area being assessed and practitioner acceptance) can

be either taken as a measure of how proactive the building industry is in creating

positive change or its responsiveness to market demand. However, public authorities

are increasingly using market-based tools as a basis for specifying a minimum

environmental performance level for their new facilities. Certainly these tools have:

Given focus to green building practice. Whereas design guidelines provide a

broader range of issues, assessment methods give structure and priority, and as

such provide greater strategic advice to the design team. The structure and

organization of environmental knowledge is proving to be as important as the

individual elements.

Enabled building performance to be described comprehensively. Performancebased indicators, where actual amounts of resource use and loadings enable

improvements to be demonstrated relative to known or declared benchmarks and to

be aggregated to establish overall patterns of consumption or environmental

loading. Since the field is still maturing, it is not possible to formulate performancebased indicators for all of the issues covered within a comprehensive building

environmental assessment. Proscriptive requirements are often specified as proxies

for actual performance values, e.g., proximity to public transit stops is often used as

a proxy for increased use of mass transit, reduced use of automobile for commuting

and hence reduced energy consumption and pollution and reduced traffic

congestion.

Assisted in re-shaping the design process. Improving the environmental

performance of buildings within current cost and time constraints requires a more

thoughtful, multi-discipline and integrated approach to design with all parties

involved from the start of the process. Assessment methods play a valuable role by

providing a clear declaration of the key environmental considerations and their

relative priority.

With many countries either having, or being in the process of developing domestic

assessment methods, international exchanges and coordination are increasingly

evident. In 1997, for example, the International Organization for Standardizations

Technical Committee 59 (ISO TC59) - Building Construction resolved to establish an

ad hoc group to investigate the need for standardized tools within the field of

sustainable building. This subsequently evolved and was formalized as SubCommittee ISO T59/SC17 Sustainability in building construction the scope of

which includes the issues that should be taken into account within building

environmental assessment methods.

Although life-cycle energy analyses have provided a broader view of performance

since the 1970s, it failed to enter mainstream environmental discourse at the time.

Research by Kohler [1987] and other Europeans in the late 1980s heralded the

beginning of a much more rigorous and comprehensive understanding of life-cycle

building impacts. The notion of Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) has now been generally

accepted within the environmental research community as the only legitimate basis on

which to compare alternative materials, components, elements, services and whole

buildings. Many assessment tools such as EcoQuantum (Netherlands), EcoEffect

(Sweden), ENVEST (UK) and ATHENA (Canada) adhere to the rigours of LCA.

Meaningful LCA assessment methods are usually data intensive and can involve

enormous expense of collecting data and keeping it current, particularly in a period of

considerable changes in materials manufacturing processes. Some of these tools aim

to simplify this for practical use within the design process (ENVEST), but this can

make these tools inflexible to novel design elements..

Currently none of the existing simplified building environmental assessment methods

are comprehensively or consistently LCA-based, nor do they necessarily need to be

given their primary role in market transformation. While some performance criteria in

these methods are increasingly based on conventional LCA data, their strength lies in

bringing a broader range of considerations to the assessment process while being

respectful of simplicity and practicality to make them widely accessible. Provided the

relative number of points assigned to each issue are derived through a transparent,

consensus process, widely different criteria can be legitimately combined and

aggregated to offer overall building performance scores.

But how is the widespread use of assessment methods affecting building design?

There are several direct impacts:

Firstly, it is having a profound effect in providing focus to the building/

environmental debate and offering a host of indirect benefits such as requiring

greater communication and interaction between members of the design team and

various sectors with the building industry, i.e., environmental assessment methods

encourage greater dialogue and teamwork.

Secondly, they represent an industry standard of what constitutes a green building

taking into account both the desire to improve building performance while

recognizing issues of cost and practicality.

Thirdly, they declare a set of environmental issues and assign significance to them

and organize information in an explicit manner. The pros and cons of the

categorization of environmental issues remains a relatively unexplored issue. While

the organization of environmental issues within building environmental assessment

methods has provided clarity and structure, rigid categorization can be counter to

the need to acknowledge and resolve links and synergies.

Fourthly, they provide summaries of building performance that can be used to

communicate to stakeholders. Here, the method by which the results are depicted

has a direct bearing on how various performance indicators are used and

understood and by whom.

Fifthly, they motivate innovation, encouraging materials and product suppliers to

develop new environmentally beneficial products, services and practice and to bring

down the costs of these new technologies as they reach economic production scales.

Sixthly, they provide a vehicle for both public and corporate policymaking.

The interest in quantification and assessment is much more widespread than for

building environmental performance, and this increase may be signalling a growing

mindset for demonstrated action rather than continued rhetoric. For example:

Fueled by the capability of information technologies, there is an increasing search

for indicators to measure and benchmark performance at every scale from

buildings to national progress in sustainable development.

Gann et al indicate that a new culture of performance measurement has began to

take hold across the UK construction sector particularly for production processes.

[Gann, et al., 2003] The development of a Design Quality Index (DQI) to assess a

broad range of issues is signaling interest in whole building performance

assessment to embrace considerations that extend way beyond the current interest

in environmental assessment.

There is little doubt that building environmental assessment methods have contributed

enormously to furthering the promotion of higher environmental expectations, and

have directly and indirectly influenced the performance of buildings. This success

derives from their ability to offer a recognizable structure for environmental issues and,

more importantly, provide a focus for the debate of building environmental

performance. This momentum will likely increase over the next few years, and the

systems will evolve in terms of benchmark performance requirements and level of

complexity attainable within acceptable costs. Similarly, the organizational structures

within which the methods are administered will respond to concerns over the costs of

making an assessment by streamlining the certification process and the necessary

support documentation.

Several possibilities can be postulated regarding the possible ways that assessment

methods may evolve in the longer future:

1. Assessment methods will need to be cast within a broader array of initiatives for

creating necessary change. Here, the current success that assessment methods

enjoy within both research and practice has potentially adverse consequences. By

being almost the sole focus of the debate, too much expectation may be being

placed on their ability to create the necessary change.

2. While establishing appropriate performance metrics and scales is a critical issue, a

critical challenge for developers of building assessment methods will be the

recognition and accounting for possible synergies between environmental

performance criteria. Currently, an overall building performance score is derived

from the aggregation of the points obtained within the constituent environmental

credits. As such, the selection of the performance credits is based on ensuring their

independence to avoid the possibility of double-counting. In practice, this

translates to a checklist approach where individual performance criteria of identified

and pursued in the quest for a certain overall rating. More skilled design teams

recognize that successful green design with demanding performance expectations

is as much about the interrelationship between the strategies and systems as it is

with their individual merits and consequences. The way in which assessment

methods nurture systems thinking will be an increasingly important characteristic.

3. Assessment methods will have to be recast under the umbrella of sustainability

environmental, social and economic. We are at an intriguing juncture in the debate,

let alone practice, about sustainable building. Broadening the scope of discussion

beyond environmental responsibility and embracing the wider agenda of

sustainability is an increasingly necessary requirement. Yet, in the short term, this

may create a loss of focus for improving the environmental performance of

buildings. And, because current discussions of sustainability have already been

diffused and appropriated by the here and now, an important issue will be whether

it can provide a sufficient catalyst for changing attitudes and expectations.

4. Market-based assessment methods will have to reinvent themselves to maintain

potency. This can be achieved, to a degree, through the release of updated versions.

The session Building Environmental Assessment Tools focuses on the current and

emerging role of building environmental assessment tools. Papers are solicited that

address the following issues:

The extent to which LCA methodologies can and should be integral to market place

building environmental assessment tools.

How can assessment tools balance the opposing needs for increased

comprehensiveness of assessment with ease of application?

The advantages of building-type specific versions of an assessment tool verses

single, unified versions.

How are assessment tools viewed by various stakeholders in the building industry.

The shift from building environmental assessment to sustainability assessment.

While assessment tools are currently providing a valuable role, are there long-term

problems. For example, does the categorization of environmental issues blur the

many synergistic effects between them, or will chasing a high performance score

constrain green design.

The desirability of comparing building environmental assessment tools and the pros

and cons of international standardization in a rapidly evolving field of enquiry.

The future of building environmental assessment tools how are they likely to

evolve, how will they be used and how will they dovetail with other change

instruments (regulations, codes, incentives)

Which areas or aspects of performance assessment are likely to gain in

significance in the short and long-term (e.g. existing buildings, district, etc.).

References

Kohler, N., (1987) Energy Consumption and Pollution of Building Construction,

Proceedings, ICBEM Sept. 28th - Oct. 2nd, 1987, Ecole Federale Polytechnique de

Lausanne, Lausanne Switzerland.

Gann, D.M., Salter, A.J. and Whyte, J.K. (2003) Design Quality Indicator as a Tool for

Thinking, Building Research & Information, 31 (5) September-October, pp318-333

You might also like

- University Living Learning Labs An IntegDocument17 pagesUniversity Living Learning Labs An IntegThalita DalbeloNo ratings yet

- Easy Open Data From Open Data To SustainainabilityDocument143 pagesEasy Open Data From Open Data To SustainainabilityThalita DalbeloNo ratings yet

- IPCC AR6 SYR LongerReportDocument85 pagesIPCC AR6 SYR LongerReportThalita DalbeloNo ratings yet

- Behavior Change Interventions For Reduce Energy UseDocument17 pagesBehavior Change Interventions For Reduce Energy UseThalita DalbeloNo ratings yet

- Industrial Ecology in Practice - KalundborgDocument13 pagesIndustrial Ecology in Practice - KalundborgThalita DalbeloNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Maruti SuzukiDocument17 pagesMaruti SuzukiYogesh Saini100% (1)

- TIBCO Spotfire Guided AnalyticsDocument12 pagesTIBCO Spotfire Guided AnalyticsRajendra PrasadNo ratings yet

- Impact of China On South Korea's Economy by Cheong Young-RokDocument21 pagesImpact of China On South Korea's Economy by Cheong Young-RokKorea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Resources and CapabilitiesDocument16 pagesResources and CapabilitiesSunil MathewsNo ratings yet

- Billing DataDocument210 pagesBilling Datakrishnacfp2320% (1)

- Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition Act)Document11 pagesContract Labour (Regulation & Abolition Act)Nagaraj SrinivasaNo ratings yet

- BSBLDR502 Lead and Manage Effective Workplace RelationshipsDocument24 pagesBSBLDR502 Lead and Manage Effective Workplace RelationshipsBHARATH55% (11)

- SigmaDocument554 pagesSigmatiensuper2606No ratings yet

- Aiap016379 - General Construction DocumentsDocument2 pagesAiap016379 - General Construction DocumentsmtNo ratings yet

- Financial Times USA May 30 2017 FreeMags CCDocument26 pagesFinancial Times USA May 30 2017 FreeMags CCВероника ЯременкоNo ratings yet

- Marketing Case QuestionsDocument3 pagesMarketing Case QuestionsFaye WongNo ratings yet

- Statistical Review of World Energy Full Report 2005Document44 pagesStatistical Review of World Energy Full Report 2005Ulysses CaynnãNo ratings yet

- Jio Invoice AprDocument2 pagesJio Invoice AprAARISH RIKIN GANDHINo ratings yet

- DEKRA Process Safety India BrochureDocument8 pagesDEKRA Process Safety India BrochureNishir Shah100% (1)

- Strategic Management Complete Project On McDonaldDocument88 pagesStrategic Management Complete Project On McDonaldTanzi Jutt0% (3)

- Health and Safety Principles ForDocument4 pagesHealth and Safety Principles ForAnonymous MAQrYFQDzVNo ratings yet

- Company AnalysisDocument11 pagesCompany AnalysisSumi DharmarajNo ratings yet

- Jimmy ChooDocument7 pagesJimmy ChooFatihah Onn100% (1)

- Classified Advertising: Ramadan Ramadan Timing TimingDocument2 pagesClassified Advertising: Ramadan Ramadan Timing TimingSwamy Dhas DhasNo ratings yet

- Lean Startup The Inabel ProjectDocument12 pagesLean Startup The Inabel ProjectJag FernandoNo ratings yet

- Reaping The Benefits of ISO 9001Document12 pagesReaping The Benefits of ISO 9001Rayvathy ParamatemaNo ratings yet

- TERM 1-Credits 3 (Core) TAPMI, Manipal Session 12: Prof Madhu & Prof RajasulochanaDocument20 pagesTERM 1-Credits 3 (Core) TAPMI, Manipal Session 12: Prof Madhu & Prof RajasulochanaAnikNo ratings yet

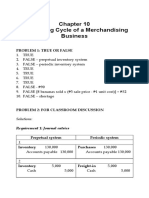

- Sol. Man. - Chapter 10 - Acctg Cycle of A Merchandising BusinessDocument65 pagesSol. Man. - Chapter 10 - Acctg Cycle of A Merchandising BusinessPeter Piper67% (3)

- Branch Grading SystemDocument10 pagesBranch Grading Systemapi-1828900100% (2)

- Internship Agreement - BDocument2 pagesInternship Agreement - Brobert sumalinogNo ratings yet

- Employee SatisfactionDocument2 pagesEmployee SatisfactiongautamNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 Entrepreneurship and Regenerative BusinessDocument34 pagesLesson 6 Entrepreneurship and Regenerative BusinessjasNo ratings yet

- Preparing and Posting Journal Entries For Brooke GableDocument5 pagesPreparing and Posting Journal Entries For Brooke GableĐông ĐôngNo ratings yet

- HRM in A Changing EnvironmentDocument4 pagesHRM in A Changing Environmentgeethark12No ratings yet

- Group 1 - MARKSTRAT - Decision - 3Document14 pagesGroup 1 - MARKSTRAT - Decision - 3Siddharth GargNo ratings yet