Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ptj3704227 PDF

Uploaded by

Dexter BluesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ptj3704227 PDF

Uploaded by

Dexter BluesCopyright:

Available Formats

Pruritus in the Elderly

Clinical Approaches to the Improvement of Quality of Life

Kenneth R. Cohen, PharmD, PhD; Jerry Frank, MD;

Rebecca L. Salbu, PharmD, CGP; and Igor Israel, MD

INTRODUCTION

Case Report

J. D., an 85-year-old female resident of a long-term-care

facility, was recently evaluated for generalized pruritus. Her

medical history includes dementia, diabetes mellitus,

peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, congestive heart

failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

osteoarthritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and a

recurrent urinary tract infection.

Over the clinical course of her disorders, she was taking

multiple medications off and on, including acetaminophen,

fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler, albuterol inhaler, ipratropium

inhaler, docusate sodium, ferrous sulfate, flunisolide nasal

spray, furosemide, lovastatin, insulin, omeprazole, and

enalapril.

These medications were discontinued to determine

whether they were the cause of the patients pruritus. The

discontinuations had no effect on her condition.

Systemic hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, and prednisone; oral amitriptyline; and topical betamethasone diproprionate ointment were used to treat her pruritic symptoms.

A review of the patients organ systems proved unremarkable. On physical examination, she was noted to be in no

distress. Her cognition was unchanged from her admission

status of mild disorientation, which was consistent with her

dementia.

The remainder of her examination was significant only for

mild excoriations on her stomach and extremities and an

erythematous rash across her buttocks.

Laboratory assessments were within normal values

except for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 11,500 mcL

with a normal differential; a random blood glucose level of

278 mg/dL; and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 42 mg/dL.

The patients pruritus has remained moderately symptomatic; only occasional relief was achieved with medications.

The cause was never determined. The purpose of the

review was to present the possible causes of the pruritus to

assist clinicians in individualizing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is an Associate Professor of Pharmacy and Health Outcomes at the Touro College of Pharmacy in New York, N.Y.

Dr. Frank is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of

Family Medicine at SUNY Stony Brook School of Medicine in Stony

Brook, N.Y. Dr. Salbu is an Assistant Professor of Pharmacy and

Health Outcomes at the Touro College of Pharmacy. Dr. Israel is

Associate Medical Director at the Parker Jewish Institute of Health

Care and Rehabilitation in New Hyde Park, N.Y.

Accepted for publication November 18, 2011.

Pruritus is the most common skin disorder in the geriatric

population.1 It is defined as an unpleasant cutaneous sensation

that provokes the desire to scratch.2 Acute itch (lasting less

than 6 weeks) may provide a protective function, but chronic

itch (lasting more than 6 weeks) is mostly a nuisance.3 The

prevalence of pruritus increases with age and can be partially

attributed to a decline in the normal physiological status of the

skin (Table 1).2,4

In a French study, a survey was sent to 10,000 randomly

selected households.5 Of 7,500 respondents, 87% reported skin

problems since birth and 43% experienced these problems

over the 2 years preceding the survey. In addition, 29% of the

respondents described their symptoms as burdensome. Of

those individuals, more than half indicated that chronic skin

disorders, with pruritus as the primary symptom, impaired

daily activities.

Moreover, in a study of skin disorders in 68 noninstitutionalized persons, two-thirds of the group and 83% of octogenarians reported medical concerns regarding their skin,

with pruritus the most frequent complaint.6 In a study conducted in Norway, itching was the predominant skin complaint in subjects ranging from 30 to 76 years of age.7

Chronic pruritus can have a significant effect on quality of

life, because therapies for acute pruritus often do not ameliorate chronic disease.8 In many people, itching is not just an

occasional problem; it can have debilitating effects, such as

sleep impairment, that can result in clinical depression. In

fact, many people with chronic itching can become so depressed that they would rather live a shorter life free of

symptoms than a longer life with pruritus.8 Studies have shown

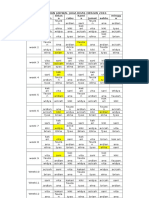

Table 1 Decline of Skin Function in the Geriatric

Population

Cell replacement

Barrier function

Chemical clearance capacity

Sensory perception

Mechanical protection

Wound healing

Immune responsiveness

Thermoregulation

Sweat production

Vitamin D production

Data from Tycross R, et al. Q J Med 2003;96:726;2 and Fenske NA,

Lober CW. Geriatrics 1990;45:2735.4

Disclosure: The authors report that they have no financial or commercial/industrial relationships in regard to this article.

Vol. 37 No. 4 April 2012

P&T 227

Pruritus in the Elderly

that the detrimental effect of chronic pruritus on quality of life

is comparable with that of chronic pain.8,9

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

As noted, chronic pruritus is one of the most common dermatological complaints of patients, especially in the elderly.

In the study by Beauregard and Gilchrest,6 two-thirds of geriatric patients reported pruritus as their major skin complaint.

The condition is more prevalent in women than in men.7,10

In an analysis of hospital-based patient registry records,

11.5% of hospital admissions in elderly patients were attributed

primarily to pruritus.1 In patients older than 85 years of age,

this incidence rose to nearly 20%. In another study, pruritus was

present in two-thirds of approximately 1,500 elderly patients in

skilled-nursing facilities.11

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The sensation of itching is closely associated with the sensations of touch and pain.12 Pruritus is stimulated by the release

of neurostimulators, such as histamine, from mast cells and

other peptides. The resulting sensation of itch is carried on

A-delta and C fibers, through the dorsal horn of the spinal cord,

and across the anterior commissure to the spinothalamic tract,

ultimately terminating in various brain centers, including the

cortex and thalamus.10,1214

Aging skin is susceptible to pruritic disorders because of the

cumulative effects that the environment has on the skin and

because of changes to the skin structure that occur as we

age.15 Loss of skin hydration, loss of collagen, impaired

immune system responses, and impaired function of the skin

as a barrier to pathogens are also involved. Impaired blood

circulation, leading to decreased perfusion to the skin, may also

occur.3 The presence of comorbid conditions, the lack of

mobility, and the increased use of medications may also

contribute to the prevalence of pruritus in elderly individuals.16

In older people, pruritus is often associated with dry skin resulting from decreased skin-surface lipids, reduced production

of sweat and sebum, and decreased perfusion.17 Collagen is

also reduced and is less soluble in geriatric populations. Moreover, because of skin folding, less surface area is able to interact

with water.18 This can result in impaired immune function and

diminished barrier repair. Altered skin pigmentation and

increased skin fragility also increase the likelihood of pruritus

in elderly adults.18

NEUROTRANSMITTERS

The release of histamine from mast cells is believed to be the

primary mediator of itching.19 This release may also cause a

vascular response that results in erythema and swelling of

the affected skin. However, because not all patients with pruritus respond to antihistamine therapy, other mediators appear

to be involved as well.19 For example, serotonin (5-HT) is

released when platelets aggregate and stimulate serotonin

receptors. 5-HT3 antagonists have been shown to reduce

itching.20

Acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, is also involved in pruritus, particularly in patients with atopic dermatitis.21 These

patients have dry, thickened skin and an increased sensitivity

to acetylcholine.

228 P&T

April 2012 Vol. 37 No. 4

Prostaglandins (lipid compounds produced in cells by the

enzyme cyclooxygenase) are involved in the chemical cascade

created by histamine and may potentiate pruritic symptoms

caused by histamine and possibly other agents.22

Nerve fibers containing substance P, a neuropeptide, congregate around sweat glands and blood vessels and can lead

to neurogenic inflammation.23 In addition, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) can produce itching.23 High levels of substance P, VIP, somatostatin, and neuropeptide Y occur in

pruritic skin lesions.23,24 In addition to histamine, activated

mast cells release chymase, tryptase, leukotrienes, and interleukins, which can lead to pruritus.23

CLASSIFICATION AND ETIOLOGY

The classification of pruritus begins with the disorders

etiology.13 The origin can be both dermal and neuropathic.

Pruritus can also originate centrally, or the cause can be

psychogenic.2

Dermatological Causes

The most common dermatological change that occurs in

elderly people is xerosis, or dry skin.25 Environmental conditions or excessive loss of moisture from the epidermis may

result in xerotic lesions, which can crack and split. This in turn

can cause pruritus and bleeding, possibly leading to infection.

Other causes of dry skin include weather extremes, such as

cold air or low humidity, and excessive exposure to water,

especially in colder climates.2527

Excessive exposure to the sun can also lead to a variety of

skin irritations, including sunburn, or it can exacerbate further

drying of xerotic skin lesions.26,27

Scabies, an extremely pruritic skin disorder, commonly

occurs in the elderly, especially those confined to long-termcare facilities.28 Scabies results from infection by the hostspecific mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. Each year, more

than 300 million cases of scabies occur worldwide, and the

infection is highly contagious in institutional settings.28 The

disorder is diagnosed by microscopic examination of skin

scrapings under mineral oil.29

Atopic dermatitis, or eczema, is a recurring inflammatory

skin condition that is often associated with allergic disorders,

such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.30 Exposure to an allergen provokes the release of histamine, which can result in pruritus.

Pruritus is also associated with contact dermatitis. Detergents used in institutional bedding and clothing, as well as the

materials used in the manufacturing of these garments, have

been implicated. Other irritants include fiberglass and environmental cleaning agents.

Infection (e.g., tinea, candidiasis, and herpesvirus) is another

important cause of pruritus. Patients with certain viral infections, such as measles or rubella, commonly experience

intense itching.

Bacterial infections can also cause pruritus; this usually

occurs after scratching has damaged the skin, which allows

bacteria to colonize the affected area. Fecal bacteria may be

transferred to the skin from contaminated hands, or dermal

bacteria, such as streptococci or staphylococci, may grow in

open wounds.29

Pruritus in the Elderly

Neuropathic and Neurogenic Causes

Damage to nerve fibers or to the brain can lead to a particular form of pruritus known as itch without rash.31 This type

of neuropathic itching is processed in the thalamus after the

stimulation of dorsal horn neurons. The itching can be caused

by a variety of nerve-related disorders, including multiple sclerosis and brain tumors.31

After a stroke, damage to the central nervous system (CNS)

can lead to neurogenic pruritus.32,33 In these cases, the sensation of intense itching arises from lesions in the thalamus or

parietal lobe without localized skin irritation.

Pruritus has also been associated with neuralgia following

a herpes infection.34

Psychiatric Causes

Pruritus can result from a number of psychiatric disorders.

In one study, 70% of patients with chronic pruritus had at least

one of six psychiatric diagnoses, including dementia, schizophrenia, primary depressive disorders, personality disorders,

and behavioral disorders.35

The French Psychodermatology Group proposed three compulsory criteria for a diagnosis of psychogenic pruritus:36

localized or generalized itch without skin lesions

chronic itch (lasting more than 6 weeks)

absence of a somatic cause

In addition, at least three of the following seven criteria

should be present:

a chronological relationship with an event that could have

psychological repercussions

stress-related variations in the intensity of the itching

nocturnal variations in symptoms

predominance of the itching during rest or inaction

presence of a psychological disorder associated with itching

itching that can be improved with psychotropic drugs or

psychotherapy

bile salts or of endogenous opioids have been implicated as

well.40 Other causes of neurogenic itch associated with cholestasis include the release of intrinsic opioids or the extrinsic

administration of opiate drugs.41 The symptoms of cholestatic

pruritus are usually more pronounced at night.

Pruritus occurs in up to 90% of patients with renal failure or

uremia who are receiving maintenance dialysis.42 The most

common cause is xerosis secondary to dialysis, which affects

the balance of calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus. In addition, the patients uremic condition acts as a chronic inflammatory process, causing the releasing of proinflammatory

cytokines and histamine.43 Itching does not occur in patients

with acute renal failure.44

The presence of pruritus is one of the four diagnostic hallmarks of diabetes mellitus (i.e., polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, and pruritus), although early studies found that itching was

present in only 7% of patients with diabetes.42 The cause of the

intense itching experienced by diabetic patients is unclear,

but it may be related to secondary conditions, such as xerosis

or infections.45 Interestingly, the control of elevated blood

glucose levels often leads to a marked reduction in symptoms.

Several case studies have identified generalized pruritus as

a symptom of thyroid disease. In these patients, the most common cause of pruritus was the presence of antithyroid antibodies.46 Pruritus in patients with hyperthyroidism may be

caused by the warm, moist skin that accompanies this disorder,

although the exact cause is unknown.47 Hyperthyroidism can

also cause cholestatic jaundice, which has been associated

with pruritus.48 In patients with hypothyroidism, pruritus is

usually the result of xerosis.47,49 Treatment of the underlying

condition usually results in the resolution of pruritic symptoms

in patients with thyroid disease.38,47,49

Hematological disorders can also cause pruritus.47 For example, the onset of Hodgkins disease is often preceded by an

intense, burning itch.50 Moreover, generalized pruritus occurs

in 25% to 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (a bone marrow disease associated with an abnormal increase in the number of blood cells).51 Adult-onset eczema has been identified as

a marker for leukemia.50

Pruritus Associated With Systemic Diseases

Drug-Induced Pruritus

Systemic diseases often lower the itch threshold. In this

setting, a mild stimulus can trigger an exaggerated pruritic

response in some patients. Comorbid xerosis resulting from

decreased skin hydration may exacerbate pruritus in older

patients with systemic diseases. This is especially true for

institutionalized geriatric patients or for individuals with dementia whose general inactivity allows them to be distracted

by pruritic stimuli.37

Patients with liver disease often experience pruritus.3840

Itching is a presenting symptom in 25% of those with jaundice

from biliary obstruction or other causes, such as cirrhosis, pancreatic cancer, or hepatitis. 38 It has been hypothesized that

pruritus in these patients might be the result of an accumulation of bile in nerves or skin cells, but this remains unproven.38

Increased levels of plasma lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and

of serum autotoxin have been obser ved in patients with

cholestatic pruritus.39 Autotoxin is involved in the conversion

of lysophosphatidylcholine to LPA. High concentrations of

Drug-induced pruritus typically results from an allergic

reaction to an active medication or to the fillers or preservatives used in the drugs preparation.52 Drugs can also cause

pruritus indirectly by affecting the liver or kidneys, which

leads to itching owing to liver failure and jaundice or to renal

failure with uremia.52 Some medications, such as angiotensinreceptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme

(ACE) inhibitors, mediate the release of bradykinins, resulting

in pruritus.52

Pruritus may occur as a secondary response to systemic side

effects involving the liver or kidney after treatment with amiodarone (Cordarone, Wyeth/Pfizer), ticlopidine (Ticlid, Roche),

some antibiotics (e.g., macrolides and carbapenems), and

psychotropic agents (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants and

neuroleptics).53,54 Statins (HMGCoA reductase inhibitors),

antimicrobials, chemotherapeutic agents, and antiseizure medications, such as phenytoin (Dilantin, Pfizer), carbamazepine

(Tegretol, Novartis), and topiramate (Topamax, Janssen), may

Vol. 37 No. 4 April 2012

P&T 229

Pruritus in the Elderly

cause a rash or skin lesions, with resulting pruritus.5456

Opioids can cause pruritus, most likely as an adverse effect

rather than as an allergic reaction. Pruritus occurs in 2% to 10%

of patients who have been treated with opioids; the mechanism

is thought to be related to the release of histamines or to a

centrally mediated process.57

Some drug reactions that result in pruritus can be severe

and potentially life-threatening. The appearance of acute

urticaria and angioedema, for example, should be considered

a medical emergency, requiring the immediate discontinuation

of the offending agent, followed by treatment with parenteral

antihistamines and prednisone.58

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), also known as Lyells

syndrome, is one of the most serious drug-related skin

reactions. It involves the initial development of erythema, followed by large vesicles and mucosal erosions. The exposure

of underlying tissue, with fluid loss, can lead to systemic infection and, potentially, fatal septic shock. Phenytoin, barbiturates, penicillin, and sulfonamides are known to cause TEN.58

EVALUATION

Although it can be difficult to identify the cause of pruritus,

therapy is a fairly straightforward process after the origin has

been determined. Treatment consists mainly of removing or

avoiding the offending agent or allergen in conjunction with the

use of topical or systemic drugs.

Medical History

A detailed medical history should be obtained if the primary cause of the patients pruritus is to be identified. The following factors must be considered: 59

1. Initiation of symptoms. Understanding when the pruritus started and its relationship to the introduction of a new

environmental factor, detergent, soap, or food is important. It

should also be determined whether the itching is generalized

or localized, and its location should be pinpointed; this information may point to a primary cause of the disorder. For example, an itch that is localized to the groin or to the anal area

may have a specific cause, such as a fungal or parasitic infection, or it may be secondary to another disorder, such as hemorrhoids.

2. Presence or absence of lesions. The presence or absence of a lesion can help point to the cause. For example, a

pruritic rash that waxes and wanes may indicate an allergic

reaction.

3. Time of day when symptoms are worst. Knowing

when symptoms are most severe may guide the diagnosis toward a primary cause, such as mites or other parasites, which

tend to be more active at night. Pruritus that is worse at bedtime could also be related to irritation from bedding.

4. Identifying what makes the condition better. Some

circumstances may improve the condition, such as immersing

the affected area in cold water or avoiding certain clothes or

soaps.

When seeking a secondary cause, the clinician must consider the presence of other disorders. For example:60

230 P&T

April 2012 Vol. 37 No. 4

Polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia may indicate the

presence of diabetes mellitus.

A history of anxiety, palpitations, or hair loss may indicate

that the pruritus is associated with hyperthyroidism.

A pruritic patient who is chronically fatigued may have

concomitant hypothyroidism.

Generalized pruritus accompanied by dark brown urine,

abdominal pain and bloating, and yellowing of the skin and

eyes may point to a hepatic origin.

Pruritus accompanied by weight loss may signify an occult neoplasm.61

The presence of diabetes mellitus, liver disease, a thyroid

imbalance, or neoplasia may indicate that the pruritus is

a secondary condition.62

Other important aspects of the patients medical history

include:63,64

Surgery. Determining whether the patient has had surgery for a chronic biliary disorder or has had cancerous

tissue removed can help pinpoint a secondary cause of the

itching.

Medications. Drugs can be a primary cause of chronic

pruritus, and a detailed history of their intake must be

obtained. Noting a relationship between the start of drug

treatment and the beginning of itching could be the key

to identifying its cause. Conversely, a history of improvement after the withdrawal of a drug is also significant.

Allergies. Understanding medication allergies and crosssensitivities is helpful. Well-known cross-sensitivities,

such as penicillin and cephalosporin, can be quickly resolved. Lesser-known cross-reactions should be investigated, especially if the timing of the beginning of the itching coincides with the introduction of a new drug. The

clinician should also investigate the patients use of overthe-counter medications and the cross-reactivity of those

drugs with prescribed agents.

Social history. A history of social behaviors, including

the use of illicit drugs and alcohol, can also assist the

clinician. The recreational use of illicit drugs, such as

opiates, amphetamines, and cocaine, may indicate that a

generalized pruritus is secondary to this behavior.

Family history. A family history of medical conditions

associated with secondary pruritus is important. The occurrence of diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, or liver disease in other family members may assist the clinician in

reaching a diagnosis.63

Review of systems. A review of the patients organ systems, besides the skin, is an important part of the medical

histor y, as accompanying complaints may guide the

clinician toward a diagnosis of secondary pruritus. Symptoms associated with other organ systems should be

considered, and a further workup should be performed

to exclude specific conditions, based on findings from

the initial review. 64

Physical Examination

The physical examination of a patient with pruritus should

start with a general evaluation.

Pruritus in the Elderly

Vital signs must be assessed. The presence of fever (i.e., a

temperature of more than 100.8oF) may indicate that the pruritus has been caused by an infectious process.

Assessment of the skin, of course, is the most important part

of the physical examination.65 The clinician must check the

skins coloration. The presence or absence of erythema in the

areas affected by the itching can help in diagnosis, especially

infection. Hemorrhage may signify a secondar y cause of

pruritus, such as neoplastic disease. Jaundice may indicate

itching related to liver disease.

During the skin examination, the clinician must also look for

lesions. Pruritic vesicles on the skin are a hallmark of viral infections, such as varicella (chickenpox). Larger lesions (bullae) could be the result of bacterial infections, such as impetigo, or autoimmune disorders. Excoriations in the affected

areas signify the intensity of the itching as well as the possibility of secondary infection, because the barrier properties of

the skin might have been jeopardized. Scaling and cracks in

the skin are hallmarks of xerosis. Localized, itchy macules or

papules may indicate an atopic reaction to an allergen.59

A simple touch of the skin to assess the warmth of the

affected area helps in identifying an infection. The clinician may

palpate the skin for fluctuance when an abscess is suspected

of causing pain and itching. Subcutaneous or subepidermal

lesions should be assessed to determine the need for a biopsy.

The clinician should also examine the skin for tissue turgor

to assess general hydration. In elderly patients, the elasticity

of the skin tends to be lost, so the tenting that is typically seen

in patients with low turgor may be the result of aging, not

dehydration, in these individuals.63

Checking for dermatographism is an easy test to perform.

The clinician strokes the patients skin using the dull side of

an object in a linear motion. If the line remains elevated and

erythematous, the result is considered positive. A positive test

indicates that the patient has overly sensitive skin and that histamines have been released in response to the mild trauma.

This finding usually indicates that an antihistamine should be

prescribed.

Thickening of the skin in a pruritic area can indicate the presence of chronic inflammation, which can result from continuous scratching or irritation.66

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory assessments may be helpful in identifying the

cause of pruritus, but they usually play a supportive role in the

physical examination. The complete blood count might show an

increased white blood cell (WBC) count. A high neutrophil

count, with a large number of immature neutrophils (left shift),

would indicate the presence of a bacterial infection. An elevated

WBC count showing an increased number of eosinophils may

indicate an allergic reaction or the presence of a parasitic infection. A high lymphocyte count, by contrast, may indicate a

viral infection. The presence of any abnormal WBC counts, as

well as the presence of abnormal WBCs, should be reviewed

and considered in terms of a neoplastic process.67

Chemistry panels may indicate the presence of a secondary

cause of the itching. Elevated bilirubin levels confirm an

observation of jaundice, and elevated alkaline phosphatase

levels would pinpoint the cause of the jaundice. Elevated

glucose levels might point to diabetes as a cause of the pruritus. Thyroid-function studies can identify abnormal activity in

the thyroid gland, which may be manifested as pruritus.46

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), although generally nonspecific, may be increased in autoimmune connective-tissue disorders or in infectious diseases, and it may be

extremely high in the presence of neoplastic disease.68

TREATMENT

General Measures

In the elderly, the management of pruritus poses a unique

challenge. Elderly patients with cognitive impairment may

make it impossible for them to identify a cause-and-effect

relationship between the pruritus and the routine activities of

daily living, or physical impairments may prevent them from

applying topical treatments.59 The management of pruritus in

this age group requires a patient-specific approach, in which

treatments are tailored to the patients mental and physical

disabilities, as well as to concurrent disease states, the severity of the pruritic symptoms, and the potential adverse effects

of available treatments.

Patient education is the first step in alleviating nonspecific

pruritic symptoms in elderly individuals. Patients should be

counseled to break the itchscratch cycle. Scratching can

cause increased cutaneous inflammation, thereby worsening

the itch.59 The cessation of scratching, therefore, may alleviate

the secondary irritation caused by the scratching itself. Moreover, patients should keep their nails short to avoid further

irritation of the skin if they are inclined to scratch.

Educating patients about the nonpharmacological measures that they can take to alleviate pruritic symptoms may

decrease the need for continuous pharmacological intervention. For example, patients should be instructed to take

short baths and to avoid hot water. Applying moisturizers immediately after bathing will ensure that the skin remains well

hydrated. Ideally, moisturizers with a low pH should be used

to maintain the normal acidic pH of the skin and to preserve

the skins barrier function.59 Using a twice-daily emollient,

especially one that contains 5% or 10% urea, may be beneficial,

although trial and error is often the method used to determine

which emollient works best.3

Patients should avoid alkaline cleansers and preparations

containing alcohol, as these tend to dry the skin. Mild, moisturizing bar soaps, such as Dove (Unilever), and soaps containing lanolin and glycerin are preferred over commercially

available pure soaps, such as Ivory (Procter & Gamble), because they cause less skin flaking after use.69

Wearing light, loose clothing while avoiding irritating fabrics,

such as wool, will also benefit the patient.70 To prevent excessive heat or perspiration, patients should maintain a comfortable air temperature in their homes, allowing less than 40%

moisture content.69 Using a humidifier in the winter and an air

conditioner in the summer is recommended.

Topical Therapies

Corticosteroids

Although corticosteroids are not directly antipruritic, they

are believed to produce their therapeutic effects by alleviating

the inflammation associated with some skin conditions, such

Vol. 37 No. 4 April 2012

P&T 231

Pruritus in the Elderly

as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.70 Corticosteroids should

be used sparingly. Higher-potency steroid creams and ointments may provide an improved anti-inflammatory response,

but they also put the patient at increased risk for adverse effects, including skin atrophy, telangiectasia, and suppression

of the hypothalamuspituitary axis.70

Topical corticosteroids should be used with caution in the

elderly; these individuals may be particularly susceptible to the

skin-thinning effects of these drugs.70

Topical Immunomodulators

The topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic, Astellas) and pimecrolimus (Elidel, Novartis) are commonly used

in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. These agents are nonsteroidal selective inhibitors of the production and release of

inflammatory cytokines in T cells and of other pro-inflammatory mediators in mast cells.71

In a randomized trial comparing pimecrolimus cream 1%

with placebo in patients with atopic dermatitis, 56% of the

pimecrolimus group experienced a significant reduction in

the severity of pruritus compared with 34% of the placebo

group within 48 hours after treatment (P = 0.003).70

In another study, Stnder et al. evaluated the efficacy of

tacrolimus 0.1% and pimecrolimus 1% in patients with prurigo

nodularis (pruritic nodules of an unknown etiology) and in

patients with localized or generalized pruritus.72 Of the 20

patients who received these medications, eight (40%) achieved

a complete cessation of itching (a reduction of 70% to 90%).

Adverse drug effects included stinging and burning at the

application site.

If tolerated, topical immunomodulators might be a good

option for elderly patients with pruritus, because thinning and

atrophy of the skin are not a concern.

Coolants

Menthol and phenol are cyclic terpene alcohols that occur

naturally in plants. They affect delta-A nerve fibers, which

transmit the sensation of cold.73 The cooling sensation provided

by these agents may alleviate itching.

Although the optimal concentration of menthol has not been

established, products containing 1% menthol are commonly

used to relieve pruritus.74 With favorable safety and toxicity

profiles, menthol is a good option for relieving pruritus in

elderly patients.

Local Anesthetics

Agents that contain local anesthetics, such as lidocaine

(Lidoderm, Endo) and lidocaine/prilocaine (Emla, AstraZeneca), may relieve itching, especially when they are applied

with occlusive dressings of cloth or nylon.73

A local anesthetic made by Abbott, pramoxine HCl (also

known as pramocaine) has antipruritic properties and has

been used in hemodialysis patients with uremic pruritus.75

Prax Lotion (Ferndale) is another product that contains

pramoxine.

Polidocanol is a non-ionic surfactant with moisturizing and

local anesthetic properties, both of which help to ameliorate

pruritic symptoms. In an open-label study, polidocanol lotion

3%, when combined with urea 5%, significantly reduced pruritus

in patients with xerotic disorders, including atopic dermatitis,

contact dermatitis, and psoriasis.76

Capsaicin

As the main capsaicinoid in chili peppers, capsaicin exerts

its antipruritic effect by desensitizing sensory nerve fibers.77

It is beneficial in the treatment of neuropathic, systemic, and

dermatological pruritus. Adverse effects include pain, burning,

and stinging at the application site, which may cause patients

to stop treatment prematurely.

In a single-blind study involving healthy volunteers, the topical anesthetic cream EMLA (lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%)

was applied 60 minutes before capsaicin cream 0.075% was

applied on one forearm and before placebo was applied on the

other forearm.78 After 5 days of three-times-daily application,

pretreatment with Emla significantly reduced the burning

sensation from capsaicin, which may promote better adherence to capsaicin treatment.

Topical Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids act at peripheral sites and produce analgesia

through their actions on CB1 and CB2 receptors. The local

analgesic actions of agonists for CB2 receptors, such as

N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine (PEA), include the inhibition of

mast-cell function and inflammatory pain.79 PEA has been incorporated into topical analgesic preparations and has been

shown to reduce pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis,

lichen simplex, and prurigo nodularis; it has also decreased

itching associated with chronic kidney disease.80,81

Topical Antihistamines

Topical antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and pyrilamine, are used primarily to treat urticaria and insect bites.

These products are not usually used for other pruritic conditions, such as idiopathic local and generalized pruritus,

because of the side effects of erythema and skin irritation.73

Doxepin (Sinequan, Pfizer), a tricyclic antidepressant, exhibits potent histamine receptor (H1 and H2 ) antagonism. In a

double-blind study, Drake and Milikan compared the antipruritic efficacy and safety of doxepin HCl cream 5% (e.g.,

Prudoxin, Healthpoint) with a placebo vehicle in patients with

lichen simplex chronicus, nummular eczema, or contact

dermatitis.82 Twenty-four hours after initiation of treatment

and for the remainder of the 7-day study, almost all of the doxepin patients experienced significantly greater relief of pruritus compared with those receiving placebo (P < 0.002).

The most common side effects included a transient stinging

sensation after application (20.7%) and drowsiness (15.5%) resulting from systemic absorption. Although the drowsiness

subsided over time, this undesirable side effect may limit the

use of doxepin cream in elderly patients.

Topical Aspirin

A double-blind placebo-controlled study in patients with

lichen simplex chronicus (an intractable, itchy dermatosis)

demonstrated a significant improvement in the symptoms of

pruritus after treatment with an aspirin/dichloromethane solution.83 This option may be helpful for elderly patients who are

unable to tolerate long-term, high-potency steroids.

continued on page 236

232 P&T

April 2012 Vol. 37 No. 4

Pruritus in the Elderly

continued from page 232

Systemic Therapies

Antihistamines

Traditionally, the treatment of pruritus associated with various skin disorders has focused on medications that antagonize

histamine receptors. It has been proposed, however, that the

relief of itching achieved with these medications might be a

result of their sedating properties and not necessarily the

antagonism of histamine, especially in pruritic conditions such

as eczema, psoriasis, and lichen planus.84

Pruritus that results from the stimulation of histamine

receptors (as in urticaria) may be effectively treated with

antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl, McNeil

Consumer) because of their ability to antagonize histamine H1

receptors.13,75,84 The use of systemic antihistamines should be

avoided in elderly patients because of the anticholinergic

effects of these drugs.

Pruritus that is caused by the release of histamine is mediated by H1 receptors. Therefore, the nonsedating H2 receptor

antagonists, such as loratadine (Claritin, Schering-Plough)

and fexofenadine (Allegra, Sanofi), are generally not effective

in the treatment of histamine-related pruritus.13 These agents,

however, have favorable side-effect profiles, are relatively safe

in older persons, and may be an option for elderly patients with

pruritic dermatoses accompanied by erythema and wheals.13

Serotonin Receptor Antagonists

The antidepressant mirtazapine (Remeron, Organon), a

serotonin (5-HT2/5-HT3) receptor antagonist, is an effective

therapy for pruritus, particularly in patients with advanced

cancer, cholestasis, or hepatic or renal failure.85 The drugs

potential for causing drowsiness may be beneficial in patients

with nocturnal pruritus.86

In an open-label study, patients with chronic pruritus

received long-term treatment with the selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine (e.g., Paxil, GlaxoSmithKline) and fluvoxamine (Luvox, Abbott).87 An antipruritic

effect was observed in 68% of the patients. Paroxetine and

fluvoxamine did not differ significantly in their efficacy. The

best responses occurred in patients with atopic dermatitis,

systemic lymphoma, or solid carcinoma.

Patients with cholestatic pruritus showed an antipruritic

response after they were treated with the antiemetic agent

ondansetron (Zofran, GlaxoSmithKline), a 5-HT3 receptor

antagonist.73

The use of serotonin receptor antagonists in elderly patients

may be limited by the occurrence of adverse effects, including

excessive CNS stimulation, sleep disturbances, and increased

agitation. It is important to consider the riskbenefit ratio of

these agents in the elderly; they should be administered only

as second-line or third-line therapy.3

Opioid Antagonists and Agonists

Opioid-induced pruritus occurs after activation of the muopioid receptors in the CNS. It is through this central process

that mu-opioid receptor antagonists, such as the generic drugs

naltrexone, nalmefene, and naloxone, are believed to have an

effect in treatment-resistant pruritus.88 These agents have

been used successfully to treat uremic and cholestatic pruritus, chronic urticaria, atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis,

236 P&T

April 2012 Vol. 37 No. 4

and opioid-induced pruritus.3,89

The activation of kappa-opioid receptors is known to reduce

pruritus. The kappa-opioid receptor agonists butorphanol (formerly Stadol, Apothecon) and nalfurafine (not available in the

U.S.) have been beneficial in patients with intractable itching

and uremic itching, respectively.59,90

Both opioid-receptor antagonists and agonists should be

used sparingly with supervision and caution in elderly patients.

These medications can put patients at risk for sedation and

insomnia, and they have a potential for abuse.

Neuroleptic Agents

The antiepileptic drugs gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer) and

pregabalin (Lyrica, Pfizer) decrease neuronal transmission.

Gabapentin is effective in the treatment of neurological pruritus (including brachioradial pruritus and notalgia paresthetica)

when used as a localized patch worn on the infrascapular area

of the back.91,92 Gabapentin is also effective in the treatment of

uremic pruritus.93

Because it is chemically similar to gabapentin, pregabalin

has been proposed as a therapy for chronic pruritus.94 Both

gabapentin and pregabalin are eliminated by the kidneys;

therefore, they must be administered appropriately in elderly

patients and in patients with impaired renal function to avoid

an overdose and adverse side effects.

Other Treatments

Phototherapy

Narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NBUVB) therapy is effective for

uremia-related pruritus and has achieved dramatic improvements in patients with severe itching.13 In a prospective study,

NBUVB was also effective in patients with generalized pruritus, although the therapys mechanism of action was not entirely clear.95 This approach may be a viable option, especially

in elderly patients, because the barrier of nonadherence to topical treatments does not come into play.

Psychotherapy

A meta-analysis was conducted to determine the effects of

psychological interventions in patients with atopic dermatitis.96

Eight clinical trials were reviewed, and numerous interventions

were evaluated, including aromatherapy, autogenic training,

brief dynamic psychotherapy, cognitivebehavioral therapy,

habit-reversal behavioral therapy, stress management, and

structured education. The investigators concluded that psychological interventions reduced the severity of eczema or the

intensity of itching and scratching in patients with atopic

dermatitis.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture interferes with the central and peripheral

transmission of itching through sensory nerve innervation,

which may be beneficial in patients with neuropathic pruritus,

prurigo nodularis, or uremic pruritus.97 Undertaking a review

of the literature, Carlsson et al. noted that pruritus had been

successfully treated with acupuncture in several trials, although the patient cohorts were small.97 Alternative modalities

may show promise for the treatment of pruritus in elderly

patients.

Pruritus in the Elderly

Treatment of Pruritus

Associated With Systemic Disease

Cholestatic Pruritus

Pruritus often develops in patients with hepatic disease. It

has been theorized that the accumulation of bile in nerve and

skin cells causes itching. Therapy in these patients should

focus on the underlying disease.38

The bile-acid sequestrants cholestyramine (e.g., Questran,

Par) and colestipol (Colestid, Pfizer) are used to treat cholestatic pruritus, and up to 80% of patients have shown a partial or

complete response to these drugs within 2 weeks.98 Because

cholestyramine and colestipol can interfere with the absorption

of many other drugs, they should not be administered within

4 hours before or after the use of certain agents. This schedule may be difficult for elderly patients who are taking multiple medications. Moreover, cholestyramine and colestipol are

associated with potentially significant gastrointestinal side effects, such as bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort.

Therefore, these drugs may need to be replaced with other

bile-acid sequestrants, such as colesevelam (Welchol, Daiichi

Sankyo).98

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated the

efficacy and safety of naltrexone (ReVia, Duramed), an oral muopioid receptor antagonist, in cholestatic pruritus.99 Patients

with intrahepatic cholestasis who received naltrexone (50 mg)

showed a statistically significant improvement in daytime and

nighttime itching (P = 0.0003 and P = 0.001, respectively) compared with patients given placebo.

Several other treatments, including rifampin (Rifadin,

Sanofi), ursodeoxycholic acid (e.g., Actigall, Watson), propofol (Diprivan, AstraZeneca), phototherapy, SSRIs, and oral

cannabinoids, have also relieved cholestatic pruritus.98,100

Uremic Pruritus

The cause of uremic pruritus is not completely understood.

Treatment should be administered in a stepwise fashion using

drugs with favorable side-effect profiles. Optimizing dialysis

has been shown to improve pruritic symptoms in elderly

patients.100 Topical treatment with tacrolimus ointment (Protopic) reduces pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease

and may be a safe option in elderly patients.101

A randomized, double-blind, controlled comparative trial

was conducted to evaluate the benefits of an anti-itch lotion

containing 1% pramoxine in patients with moderate or severe

uremic pruritus who had received hemodialysis for at least

3 months.75 Fourteen patients were treated with the pramoxine-based lotion, and 14 were given a control lotion. The

pramoxine group experienced a significant reduction in the

intensity of itching (a 61% decrease) compared with controls

(a 12% decrease) (P = 0.0072).

In another study, gabapentin was effective in patients with

uremic pruritus who had undergone hemodialysis for more

than 3 months.93 The patients received gabapentin (100 mg)

after hemodialysis for 4 weeks. After a washout period of

1 week, they received placebo for another 4 weeks. On the

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), mean pruritus scores were 6.44

(P < 0.0001), 15.00 (P < 0.001), and 81.11 (P < 0.001) during the

gabapentin, washout, and placebo periods, respectively.

Uremic pruritus has also been relieved with cholestyra-

mine, activated charcoal, thalidomide, oral opioid antagonists,

cannabinoids, capsaicin, phototherapy, pentoxifylline (Trental,

Sanofi), and acupuncture. 100,101

Hematological Malignancies

Pruritus that is directly associated with iron-deficiency

anemia responds to oral therapy with iron salts, and symptomatic improvement is seen within 14 days after treatment.100

Pruritus is also a key clinical feature of polycythemia vera.

Antihistamines, antidepressants, interferon-alpha, phlebotomy,

phototherapy, iron supplements, and myelosuppressive medications have had mixed results when used to treat the pruritus associated with this condition.102

Many other malignancies are associated with itching,

including Hodgkins lymphoma, myeloma, lymphoma, leukemia, paraproteinemia, Waldenstrms macroglobulinemia,

and mastocytosis. Pruritic patients with these malignancies

may experience relief after the underlying disorder has been

controlled.100

Many adults with HIV infection also have skin conditions,

including pruritus.103 Clinicians must keep this in mind when

treating elderly patients, and appropriate testing should be

done.

CONCLUSION

The ultimate determination of the cause of the common

complaint of pruritus remains a diagnostic dilemma and a

challenge for any physician. Identifying the cause of pruritus

in elderly patients with cognitive impairment can be even more

difficult. Every effort must be made to identify primary and

secondary causes of the disorder, and this can require excessive time and a meticulous history and physical examination.

Careful attention must be paid to even the slightest detail that

would lead the physician down the correct path.

When the cause has been determined, choosing the appropriate treatment is not always easy. The presence of comorbidities may make it difficult to select the correct treatment. In

elderly or other impaired persons, using therapies that require

a patients attention to drug schedules or other details is rife

with problems.

Physicians who treat patients with pruritus should consider

the adverse effects of all medications; be aware of patient complaints early in the process; and act in the patients best interest to improve quality of life and to eradicate discomfort.

REFERENCES

1. Yalcin B, Tamer E, Gur Toy G, et al. The prevalence of skin

diseases in the elderly: Analysis of 4099 geriatric patients. Int J

Dermatol 2006;45:672676.

2. Tycross R, Greaves MW, Handwerker H, et al. Itch: Scratching

more than the surface. Q J Med 2003;96:726.

3. Reich A, Stnder S, Szepietowski J. Pruritus in the elderly. Clin

Dermatol 2011;29:1523.

4. Fenske NA, Lober CW. Skin changes of aging: Pathological

implications. Geriatrics 1990;45:2735.

5. Wolkenstein P, Grob J, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. French people and

skin diseases. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:16141619.

6. Beauregard S, Gilchrest BA. A survey of skin problems and skin

care regimens in the elderly. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:16381643.

7. Dalgard F, Svenson A, Holm J, Sundby J. Self-reported skin morbidity in Oslo: Associations with sociodemographic factors among

adults in a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:452457.

Vol. 37 No. 4 April 2012

P&T 237

Pruritus in the Elderly

8. Kini S, DeLong L, Veledar E, et al. The impact of pruritus on quality of life: The skin equivalent of chronic pain. Arch Dermatol

2011;147(10):11531156.

9. Dalgard F, Dawn A, Yosipovich G. Are itch and chronic pain

associated in adults? Results of a large population survey in Norway. Dermatology 2007;214:305309.

10. Stnder S, Setinhoff M, Schmeltz M. Neurophysiology of pruritus. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:14631469.

11. Norman RA. Xerosis and pruritus in the elderly: Recognition and

management. Dermatol Ther 2003;16:254259.

12. Shanley KJ. Pathophysiology of pruritus. Vet Clin North Am Small

Anim Pract 1988;18:971981.

13. Tivoli Y, Rubenstin R. Pruritus: An updated look at an old problem. J Clin Anesth Dermatol 2009;2:3036.

14. Bernhard J. Itch and pruritus: What are they, and how should

itches be classified? Dermatol Ther 2005;18:288291.

15. Grundman S, Stnder S. Evaluation of chronic pruritus in older

patients. Aging Health 2010;6:5366.

16. Farange MA, Miller KW, Elsner P, Maibach H. Functional and

physiological characteristics of the aging skin. Aging Clin Exp Res

2008;20;195200.

17. Waller JM, Maibach HI. Age and skin structure and function, a

quantitative approach. I: Blood flow, pH, thickness, and ultrasound echogenicity. Skin Res Technol 2005;11:221235.

18. Waller JM, Maibach HI. Age and skin structure and function, a

quantitative approach. II: Protein, glycosaminoglycan, water and

lipid content, and structure. Skin Res Technol 2006;12:145154.

19. Stnder S, Weisshaar E, Luger T. Neurophysiological and neurochemical basis of modern pruritus treatment. Exp Dermatol

2007;17:161169.

20. Greaves MW, Wall PD. Pathophysiology of itching. Lancet 1996;

348:938940.

21. Rukweid R, Lischetzki G, McGlone F, et al. Mast cell mediators

other than histamine induce pruritus in atopic dermatitis patients:

A dermal microdialysis study. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:11141120.

22. Greaves MW, McDonald-Gibson W. Itch: Role of prostaglandins.

Br Med J 1973;3:608609.

23. Wallengren J. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of itch. Dermatol Ther 2005;18:292303.

24. Luger TA. Neuromediators: A crucial component of the skin

immune system. J Dermatol Sci 2002;30:8793.

25. Reamy B, Bunt C. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam

Physician 2011;84:195202.

26. Rogers J, Harding C, Mayo A, et al. Stratum corneum lipids: The

effect of aging and the seasons. Arch Dermatol Res 1996;288:765

770.

27. Conti A, Rogers J, Verdejo P, et al. Seasonal influences on stratum

corneum ceramide 1 fatty acids and the influence of topical

essential fatty acids. Int J Cosmetic Sci 1996;18:112.

28. Hicks M, Elston D. Scabies. Dermatol Ther 2009;22:279292.

29. Hay RJ. Scabies and pyodermas: Diagnosis and treatment.

Dermatol Ther 2009;22:466474.

30. Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A. Useful tools for the management of

atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2009;10:287300.

31. Jinks SL, Carstens E. Superficial dorsal horn neurons identified

by intercutaneous histamine: Chemonociceptive responses and

modulation by morphine. J Neurophysiol 2000;84:616627.

32. Massey EW. Unilateral neurogenic pruritus following stroke.

Stroke 1984;15:901903.

33. Kimyal-Asadi A, Kimyal-Asadi T, Milani F. Post-stroke pruritus.

Stroke 1999;30:692693.

34. Lidell K. Post-herpetic pruritus (letter). Br Med J 1974;4:165.

35. Schneider G, Driesch G, Heuft G, et al. Psychosomatic cofactors

and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic itch. Clin Exp

Dermatol 2006;31:762767.

36. Misery L, Alexandre S, Dutray S, et al. Functional itch disorder

or psychogenic pruritus: Suggested diagnosis criteria from the

French Psychodermatology Group. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;

87:341344.

37. Potts RO, Buras EM, Chrisman DA. Changes with age in the moisture content of human skin. J Invest Dermatol 1984;82:97100.

38. Mels M, Mancuso A, Burroughs AK. Pruritus in cholestatic and

238 P&T

April 2012 Vol. 37 No. 4

other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:857870.

39. Oude E, Kremer AE, Martens JJ, Beuers UH. The molecular

mechanism of cholestatic pruritus. Digest Dis 2011;29:6671.

40. Oude E, Kermer E, Beuers U. Mediators of pruritus during

cholestasis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2011;27:289293.

41. Jones EA, Bergasa NV. The pruritus of cholestasis. Hepatology

1999;29:10031006.

42. Robinson-Bostom L, DiGiavanna J. Cutaneous manifestations of

end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:975986.

43. Lugon J. Uremic pruritus: A review. Hemodial Int 2005;9:180188.

44. Peharda V, Gruber F, Kastelan M, et al. Pruritus: An important

symptom of internal diseases. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica

Adriat 2000;9:114.

45. Yamaoka H, Sasaki H, Yamasaki H, et al. Truncal pruritus of

unknown origin may be a symptom of diabetic polyneuropathy.

Diabetes Care 2010;33:150155.

46. Artantas S, Gul U, Kilic A, Guler S. Skin findings in thyroid diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20;158161.

47. Karnath B. Pruritus: A sign of underlying disease. Hosp Physician

2005 (October); 2529.

48. Hasan M, Tierney W, Baker, M. Severe cholestatic jaundice in

hyperthyroidism after treatment with 131-iodine. Am J Med Sci

2004;328:348350.

49. Polat M, Oztas P, Ilhan M, et al. Generalized pruritus: A prospective study concerning etiology. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9:3944.

50. Callen J, Bernardi D, Clark R, Weber D. Adult-onset recalcitrant

eczema: A marker of noncutaneous lymphoma or leukemia. J Am

Acad Dermatol 2000;43(2 Pt 1):207210.

51. Fitzsimmons E, Dagg J, McAllister EJ. Pruritus of polycythaemia

vera: A place for pizotifen? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed)1981;283:277.

52. Steckelings UM, Artuc M, Wollschager T, et al. Angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors as inducers of adverse cutaneous

reactions. Acta Derm Venereol 2001;81:321325.

53. Van der Linden PD, Van Der Lei J, Vlug AE, Stricker BH. Skin

reactions to antibacterial agents in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:703708.

54. Reich A, Stnder S, Szepietowski J. Drug-induced pruritus:

A review. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:236244.

55. Daras RH, Kashyap ML, Knopp RH, et al. Long-term safety and

efficacy of a combination of niacin extended release and simvastatin in patients with dyslipidemia: The OCEANS study. Am J

Cardiovasc Drugs 2008;8:6981.

56. Nigen S, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Drug eruptions: Approaching

the diagnosis of drug-induced skin diseases. J Drugs Dermatol

2003;2:278299.

57. Swegle JM, Logemann C. Management of common opioidinduced adverse effects. Am Fam Physician 2006;74:13471354.

58. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Sassolas B, Roujeau J. Drug-induced skin,

nail, and hair disorders. Drug Saf 2007;30:10111030.

59. Patel T, Yosipovich G. The management of chronic pruritus in the

elderly. Skin Ther Lett 2010;15:59.

60. Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Clinical implications of aging skin. Am J Clin Dermatol 2009;10:7386.

61. Stnder S, Weisshaar E, Mettang T, et al. Clinical classification of

itch: A position paper of the International Forum for the Study of

Itch. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:291294.

62. Cassano N, Tessari G, Vena G, Girolomoni G. Chronic pruritus

in the absence of specific skin disease. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010;

11:399411.

63. Greco PJ, Ende J. Pruritus: A practical approach. J Gen Intern Med

1992;7:340349.

64. Savin JA. Diseases of the skin: The management of pruritus.

Br Med J 1973;4:779780.

65. Keehn C, Morgan M. Clinicopathologic attributes of common

geriatric dermatologic entities. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:115123.

66. Moses S. Pruritus. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:11351142.

67. Lonsdale-Eccles A, Carmichael AJ. Treatment of pruritus associated with systemic disorders in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2003;

20:198208.

68. Hiramanek N. Itch: A symptom of occult disease. Aust Fam Physician 2004;33:495499.

69. Boccanfuso SM, Cosmet L, Volpe AR, et al. Skin xerosis: Clinical

Pruritus in the Elderly

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

report on the effect of a moisturizing bar soap. Cutis 1978;21:703

707.

Patel T, Yosipovich G. Therapy of pruritus. Exp Opin Pharmacother

2010;10:16731682.

Kaufman R, Bieber T, Helgesen AL, et al. Onset of pruritus relief

with pimecrolimus cream 1% in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: A randomized trial. Allergy 2006:61:375381.

Stnder A, Shurmeyer-Horst F, Luger TA, et al. Treatment of

pruritic diseases with topical calcineurin inhibitors. Ther Clin

Risk Manage 2006;2:213218.

Yosipovitch G, David M. The diagnostic and therapeutic approach

to idiopathic generalized pruritus. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:881887.

Patel T, Ishiuji Y, Yosipovitch G. Menthol: A refreshing look at this

ancient compound. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:873878.

Young TA, Patel TS, Camacho F, et al. A pramoxine-based anti-itch

lotion is more effective than a control lotion for the treatment of

uremic pruritus in adult hemodialysis patients. J Dermatol Treat

2009;20:7681.

Freitag G, Hoppner T. Results of a postmarketing drug-monitoring survey with a polidocanolurea preparation for dry, itching

skin. Curr Med Res Opin 1997;13:529537.

Papoiu AD, Yosipovitch G. Topical capsaicin: The fire of a hot

medicine is reignited. Exp Opin Pharmacother 2010;11:1359

1371.

Yosipovitch G, Maibach HI, Rowbotham MC. Effect of EMLA

pre-treatment on capsaicin-induced burning and hyperalgesia.

Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:118121.

Jorge LL, Feres CC, Teles VE. Topical preparations for pain relief:

Efficacy and patient adherence. J Pain Res 2010;20:1124.

Szepietowski JC, Szepieowski T, Reich A. Efficacy and tolerance

of the cream containing structured physiological lipids with

endocannabinoids in the treatment of uremic pruritus: A preliminary study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2005;13:97103.

Eberlein B, Eicke C, Reinhardt HW, et al. Adjuvant treatment of

atopic eczema: Assessment of an emollient containing N-palmitoylethanolamine (ATOPA study). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

2008;22:7382.

Drake LA, Milikan LE. The antipruritic effect of 5% doxepin cream

in patients with eczematous dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1995;

131:14031408.

Yosipovitch G, Sugeng, MW, Chan YH, et al. The effect of topically

applied aspirin on localized circumscribed neurodermatitis.

J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:910913.

Krause L, Shuster S. Mechanism of action of antipruritic drugs.

Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:11991200.

Davis MP, Frandsen JL, Walsh D, et al. Mirtazepine for pruritus.

J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:288291.

Hundley JL, Yosipovitch G. Mirtazepine for reducing nocturnal

itch in patients with chronic pruritus: A pilot study. J Acad Dermatol 2006;55:543544.

Stnder S, Bockenholt B, Schurmeyer-Horst F, et al. Treatment

of chronic pruritus with the selective serotonin re-uptake

inhibitors paroxetine and fluvoxamine: Results of an open-labelled,

two-arm proof-of-concept study. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:

4551.

Reich A, Scepietowski JC. Opioid-induced pruritus: An update.

Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:26.

Phan NJ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, et al. Antipruritic treatment with

systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: A review. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2010;63:680688.

Dawn AG, Yosipovitch G. Butorphanol for treatment of intractable

pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:527531.

Yesudian PD, Wilson NJ. Efficacy of gabapentin in the management of pruritus of unknown origin. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:

15071509.

Loosemore MP, Bordeaux JS, Bernhard JD. Gabapentin treatment

for notalgia paresthetica, a common isolated peripheral sensory

neuropathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:14401441.

Razhegi E, Eskandari D, Ganji MR, et al. Gabapentin and uremic

pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Renal Fail 2009;31:8590.

Ehrchen J, Stnder S. Pregabalin in the treatment of chronic

pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:S36S37.

95. Seckin DS, Demircay Z, Akin O. Generalized pruritus treated with

narrow-band UVB. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:367370.

96. Chida Y, Steptoe A, Hirakawa N, et al. The effects of psychological intervention on atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2007;144:19.

97. Carlsson CP, Wallengren J. Therapeutic and experimental therapeutic studies on acupuncture and itch: Review of the literature.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:10131016.

98. Kremer AE, Beuers U, Oude-Elferink RPJ. Pathogenesis and

treatment of pruritus in cholestasis. Drugs 2008;68:21632182.

99. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral

naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis: A crossover,

double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol 2002;37:717

722.

100. Lonsdale-Eccles A, Carmichael AJ. Treatment of pruritus associated with systemic disorders in the elderly: A review of the role

of new therapies. Drugs Aging 2003;20:197208.

101. Mettang T, Weisshaar E. Pruritus: Control of itch in patients

undergoing dialysis. Skin Ther Lett 2010;15:15.

102. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated

pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest 2010;40:828834.

103. Serling SL, Leslie K, Maurer T. Approach to pruritus in the adult

HIV-positive patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2011;30:101106. I

Vol. 37 No. 4 April 2012

P&T 239

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Jurnal Anak RirinDocument10 pagesJurnal Anak RirinDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Seven Cardinal MovementsDocument4 pagesThe Seven Cardinal MovementsDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Fix ObgynDocument17 pagesFix ObgynDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Referat Obgyn FixDocument29 pagesReferat Obgyn FixDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Rincian Jadwal Jaga Koas Obsgin 2016 Senin Selas A Rabu Kami S Jumat Sabtu Mingg UDocument1 pageRincian Jadwal Jaga Koas Obsgin 2016 Senin Selas A Rabu Kami S Jumat Sabtu Mingg UDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- 1830 PDF PDFDocument5 pages1830 PDF PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- UlnarClubHandweb PDFDocument2 pagesUlnarClubHandweb PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Ngeo2472 s1 PDFDocument4 pagesNgeo2472 s1 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Royal MarketingDocument12 pagesRoyal MarketingIsmail MustafaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Chapter6 - ExercisesDocument18 pagesChapter6 - Exercisesabdulgani11No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Development and Validation of RP-HPLC MeDocument5 pagesDevelopment and Validation of RP-HPLC Memelimeli106No ratings yet

- Agents Causing Coma or SeizuresDocument3 pagesAgents Causing Coma or SeizuresShaira Aquino VerzosaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Rishum 1 262421216 2Document1 pageRishum 1 262421216 2HellcroZNo ratings yet

- Bromelain, The Enzyme Complex of PineappleDocument13 pagesBromelain, The Enzyme Complex of PineappleEllisaTanNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- 2014-1 Mag LoresDocument52 pages2014-1 Mag LoresLi SacNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Medicinal and Aromatic PlantsDocument27 pagesMedicinal and Aromatic PlantsBarnali DuttaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Aamj 1752 1755Document4 pagesAamj 1752 1755Ks manjunathaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- PH Control in Fermentation PlantsDocument2 pagesPH Control in Fermentation PlantssrshahNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Manual MesoterapiaDocument95 pagesManual MesoterapiaDiana Mesquita100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elemental ImpuritiesDocument26 pagesElemental ImpuritiesDholakiaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Global Pharma MemoDocument12 pagesGlobal Pharma Memoshailesh1401No ratings yet

- GBSDocument50 pagesGBSDanik Mahfirotul HayatiNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Effectiveness of Promotion of Ayurvedic Products On Consumers in LudhianaDocument29 pagesA Study On The Effectiveness of Promotion of Ayurvedic Products On Consumers in LudhianaIqbal SinghNo ratings yet

- Vertigoheel - Double - Blind - Comparative Betahistine 2000Document6 pagesVertigoheel - Double - Blind - Comparative Betahistine 2000Cristobal CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Service VA Design Guide: Final DraftDocument75 pagesPharmacy Service VA Design Guide: Final DraftAhmad Gamal Elden MAhanyNo ratings yet

- TownscapeDocument32 pagesTownscapeCoolerAdsNo ratings yet

- Caffeine Content of Specialty CoffeesDocument4 pagesCaffeine Content of Specialty CoffeesMIRIAN FLORES CATACINo ratings yet

- 2404-Article Text-7186-1-10-20190315 PDFDocument7 pages2404-Article Text-7186-1-10-20190315 PDFnelisaNo ratings yet

- Chemical Analysis and Therapeutic Uses of Citronella Oil From Cymbopogon Winterianus: A Short ReviewDocument18 pagesChemical Analysis and Therapeutic Uses of Citronella Oil From Cymbopogon Winterianus: A Short ReviewxiuhtlaltzinNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- 1.normal Parameters For Pediatric AnesthesiaDocument5 pages1.normal Parameters For Pediatric AnesthesiaismailcemNo ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Most Notable Pharmaceutical Scandals in History?Document6 pagesWhat Are Some of The Most Notable Pharmaceutical Scandals in History?beneNo ratings yet

- Methylprednisolone AlphapharmDocument5 pagesMethylprednisolone AlphapharmMarthin TheservantNo ratings yet

- Rko Obat Agustus 2023Document40 pagesRko Obat Agustus 2023Adi IsnawanNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Oral Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery Systems - A ReviewDocument12 pagesRecent Advances in Oral Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery Systems - A ReviewChinna B PharmNo ratings yet

- Acyclovir The Best Antiviral Drug Synthesis PaperDocument7 pagesAcyclovir The Best Antiviral Drug Synthesis Paperapi-309281593No ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument3 pages1 PBHaola andaniNo ratings yet

- Case Summaries - Contract Law Unit 1Document10 pagesCase Summaries - Contract Law Unit 1Laura HawkinsNo ratings yet

- Formulation & Evaluation of SMEDDS of Low Solubility Drug For Enhanced Solubility & DissolutionDocument18 pagesFormulation & Evaluation of SMEDDS of Low Solubility Drug For Enhanced Solubility & DissolutionJohn PaulNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)