Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abdominal Pain, Chronic

Abdominal Pain, Chronic

Uploaded by

BalaKrishnaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abdominal Pain, Chronic

Abdominal Pain, Chronic

Uploaded by

BalaKrishnaCopyright:

Available Formats

Starship Childrens Health Clinical Guideline

Note: The electronic version of this guideline is the version currently in use. Any printed version can

not be assumed to be current. Please remember to read our disclaimer.

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Introduction

Incidence

Aetiology

Clinical Assessment

Formulation

Investigations

Management

Prognosis

Conclusion

References

Introduction

The generally accepted definition of this condition is three or more bouts of pain severe enough to

affect activities (usually school attendance) over a period of not less than three months. For some,

the duration of three months is too long and intervention may need to occur earlier. Most children

with this syndrome have a poorly understood yet easily recognisable condition for which an organic

cause remains elusive. The approach adopted must be based on a thorough clinical assessment of

the child.

Incidence

About forty years ago it was suggested that this condition affected 10 to 15 % of school children in

Britain. A more recent community survey in North America found a prevalence of about 20% .The

precise incidence in New Zealand is unknown but experience suggests that it is probably similar to

overseas estimates. Chronic abdominal pain is one of the three common pain syndromes of

childhood; the other two are headaches and recurrent limb pains.

Aetiolog

y

Attempts to clearly distinguish organic from functional abdominal pain are fraught with difficulty as

these two influences are not mutually exclusive in children. Psychological complications of organic

disease are common and even in children with purely functional disorders, organic factors may

contribute to symptomatology.

Despite many studies, the causes of the chronic abdominal pain syndrome in children remain

unknown. The pain is not simply due to social modelling or a means to avoid school although in

some cases either or both of these factors may be important. Studies examining intestinal

permeability, dysmotility, abnormal autonomic responses, H. pylori infection and carbohydrate

(lactose and sorbitol) malabsorption have not produced consistent results. They are plagued by

selection bias (most subjects coming from tertiary institutions), lack of controls, and the use of

techniques that cannot be reproduced. Even when a putative cause is identified it is clear that

other factors must be involved. An example of this is carbohydrate malabsorption. Though lactose

malabsorption is common only a minority of subjects appear to be affected symptomatically.

Defining the role of psychological factors has been even more difficult. Though some studies have

suggested that environmental stressors are responsible, others have indicated the opposite.

Clearly, other factors must be involved because not all children who suffer adverse life events

develop abdominal pain.

It is not surprising therefore that the most useful approach is a biopsychosocial one where the

recurrent abdominal pain is viewed as the childs response to biological factors, influenced by

temperament (the childs developing personality) and reinforced by the family and school

Author:

Editor:

Dr Ralph Pinnock

Dr Raewyn Gavin

Abdominal Pain, Recurrent in Childhood

Service:

Date Reviewed:

General Paediatrics

April 2012

Page:

1 of

7

Starship Childrens Health Clinical Guideline

Note: The electronic version of this guideline is the version currently in use. Any printed version can

not be assumed to be current. Please remember to read our disclaimer.

environment.

Author:

Editor:

Dr Ralph Pinnock

Dr Raewyn Gavin

Abdominal Pain, Recurrent in Childhood

Service:

Date Reviewed:

General Paediatrics

April 2012

Page:

2 of

7

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Clinical

Assessment

The logical approach to the child with chronic abdominal pain begins with a detailed history and

physical examination.

With encouragement even young children are able to indicate by pointing with one finger the site of

maximal intensity of the pain. John Apley (the paediatrician who first described this syndrome)

observed that the further the site of maximal pain is from the umbilicus, the greater the likelihood of

organic disease. Children often have difficulty describing the character of the pain but are usually

able to describe any radiation. Night-waking suggests peptic ulcer disease as does pain that is

aggravated by meals .The latter may also be a symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux particularly

when associated with vomiting. It is important to obtain a detailed history of the frequency and

character of the childs bowel motions. Older children are often embarrassed to discuss their bowel

motions and it may be necessary to keep a diary. Blood in the bowel motions, fever, weight loss,

arthritis and skin rashes are indicators of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Sudden onset of

abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting or pallor suggests abdominal migraine

If the childs diet contains excessive amounts of lactose or sorbitol (as an artificial sweetener)

restricting these should result in an improvement in symptoms if their malabsorption is responsible

for pain and flatulence.

Drugs that produce abdominal pain include tetracyclines (oesophagitis) and non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents (gastritis).

Specific enquiry should be made for a family history of irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer,

celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and migraine.

The best way to assess the severity of the pain is to find out how much it interferes with the childs

daily activities.

In younger children chronic abdominal pain may be a manifestation of separation anxiety. With

older children and adolescents, time should always be taken to interview the patient alone. During

this interview concerns regarding the cause of the pain are explored and stressors in the home and

school environments are discussed. Parental conflict, concerns regarding academic achievement,

peer relationships, bullying, substance abuse, and sexuality are all potential areas of concern for

older children and adolescents (HEADSS assessment). The possibility that the child or adolescent

is depressed should always be considered.

It is always helpful to ask the parents and the child what they think may be causing the abdominal

pain .It is not uncommon for them to be worried that the pain might be due to a serious disease

e.g. leukaemia which can easily be excluded on clinical assessment and a blood count.

Physical examination must include an assessment of growth and general nutrition. A complete

physical examination may detect other clues to underlying disease processes (e.g. clubbing in

chronic inflammatory bowel disease) and always provides reassurance to the child and family that

their concerns are being taken seriously. Abdominal examination focuses on areas of tenderness,

organomegaly and masses. Rectal examination is useful in detecting faecal impaction but is not

always indicated. However, it is always important to inspect the perianal area for the presence of

fissures and skin tags.

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Formulatio

n

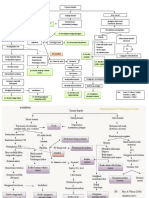

By the end of the clinical assessment it is usually possible to classify the childs presentation into

one of six categories.

1. Chronic or Recurent Abdominal Pain Syndrome

This is the commonest of the five syndromes and occurs in children between the ages of 5 and 12

years. The pain is ill-defined, periumbilical and is unrelated to meals or the passage of bowel

motions. It may be accompanied by pallor, nausea and headache. The physical examination and

screening tests are entirely normal.

2. Constipation

Pain is a feature of constipation throughout childhood and adolescence. Older children are often

reluctant to discuss their bowel motions and once toilet- trained many parents do not pay much

attention to the frequency of their childs bowel motions. If uncertainty remains then including their

frequency as part of a pain diary is helpful. Anal fissures manifesting as fresh blood on a

constipated stool may lead to reluctance to the passage of further motions and result in abdominal

pain

3. Peptic Ulcer Disease

Clues that the pain may be due to peptic ulcer disease are night-waking, pain related to meals and

a positive family history. The pain is usually epigastric but may be periumbilical. The underlying

pathology is either frank ulceration or gastritis. Functional dyspepsia is only diagnosed after

endoscopy.

4. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

This diagnosis is more common in adolescence and initially only a few suggestive features may be

present making the diagnosis difficult until further symptoms arise. It should be entertained when

abdominal pain is relieved by defaecation or associated with a change in stool frequency or

consistency. The stools may vary in consistency from hard to loose and watery. Straining at stool,

urgency, the passage of mucus, bloating and a sensation of abdominal distension are all features

of this syndrome. The pain is often cramping and though it may be located anywhere in the

abdomen it is usually maximal in the lower quadrants. Physical examination is usually normal but

sometimes there is tenderness in the lower quandrants.

5. Abdominal migraine

This is likely in children who have a sudden onset of episodic midline abdominal pain lasting

between 1 and 72 hours. Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, pallor and other vasomotor symptoms are

common and least 2 should be present to make the diagnosis.

6. Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Recurrent abdominal pain is a prominent feature of Crohns disease, whilst in ulcerative colitis it is

less prominent; it is usually associated with the passage of stool and more likely to be associated

with bloody diarrhoea. Fatigue, weight loss, night-waking and a positive family history (in 30 % of

cases) are all further pointers to these diseases.

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Investigation

s

These follow logically from the history and examination and can be divided into screening

investigations and those that are used to confirm or exclude specific diagnoses (Table1).

A full blood count and ESR (or c-reactive protein) should always be performed. Faeces should be

tested for occult blood and examined for the presence of red or white cells, bacteria and parasites.

A normal urinalysis helps exclude atypical presentations of urinary tract infections. An abdominal xray may help confirm the clinical impression of constipation by demonstrating faecal loading.

The presence of anaemia, thrombocytosis, iron deficiency, elevated ESR or C-reactive protein and

reduced serum albumin, may all indicate chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

An ultrasound is useful in excluding suspected gallbladder, renal or pelvic (ovarian cysts) disease

but has a very low yield when used indiscriminately in all children with chronic abdominal pain.

Endoscopy is the investigation of choice to confirm or exclude peptic ulcer disease, antral gastritis

or oesophagitis. Biopsies may show evidence of H. pylori infection.

Colonoscopy is indicated if chronic inflammatory bowel disease is suspected. Biopsies will help

clinch the diagnosis. Barium contrast studies are helpful in defining the extent of the disease.

Table 1: Investigations In Children With Chronic Abdominal Pain:

Screening:

In selected cases:

Full blood count

Abdominal X-ray

ESR (or C-reactive protein)

Abdominal ultrasound

Stool examination (including occult blood)

Endoscopy (and biopsy)

Urinalysis

Barium contrast studies

Managemen

t

Successful management is dependant on an accurate diagnosis.

Not surprisingly the greatest difficulty is encountered with the non-specific recurrent abdominal

pain syndrome. There is no place for rigid guidelines and one depends on clinical judgement in

deciding on the most effective approach, which is based on thorough clinical assessment.

One of the most important aspects of management is parental reassurance. Fears of specific

underlying diseases need to be confidently allayed. Parents need to know that this is a common

well-recognised but poorly understood condition. A diary kept by the child with parental assistance

is an easy way to confirm the frequency, duration and associations of the pain.

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Diary for recording the frequency and associations of the pain

Date:

Time:

What I was doing when the pain started

How bad my pain was (1 to 3 1= mild 3= the worst pain)

How long my pain lasted

What made my pain better

The role of environmental stressors need to be discussed in a non-judgmental way. Most parents

are aware that stress can produce real pain. It makes sense to ensure that any bullying at school,

concerns regarding academic progress or poor peer relationships are all sympathetically

addressed. Any pain is much easier to cope with when the home and school environments are

perceived as supportive. School attendance has to be actively managed in its own right as

absenteeism is much more difficult to address once it has become entrenched and affected the

childs self-confidence. The non-specific abdominal pain is often most severe in the morning but

rarely lasts more than an hour it is important to take the child to school once the pain starts

settling. Similarly any sick bay attendances should be as short as possible and sending the child

home from school is always the last resort. It is helpful to gain the support of teachers to ensure

that the child and the pain are appropriately managed. With regular follow-up and support from

their GP most children with recurrent abdominal pain syndrome will improve or at least reach a

stage where they can cope with daily activities. Cognitive behavioural therapy may be helpful.

When to refer the child with Chronic Abdominal Pain to a Paediatric Clinic:

Diagnostic uncertainty

Excessive parental anxiety

School absenteeism

Suspicion of serious gastrointestinal disease (persistent vomiting, weight loss, dysphagia)

Night-waking

Pain localized away from the umbilicus

Poor growth or weight loss

Extra-intestinal symptoms e.g. fever, rash, mouth ulcers, joint pain)

Blood in stools

Anaemia

Raised ESR

Family history of peptic ulcer or inflammatory bowel disease

The management of the other conditions responsible for recurrent abdominal pain is as below:

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Management of specific conditions causing chronic abdominal pain

Constipation: see constipation guideline

Laxatives (e.g. Movicol, Lactulose, bulking agents)

Increase dietary fibre

Regular toileting (5 minutes on toilet 20 minutes after breakfast and evening meal)

Star chart for younger children

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Explanation

Avoiding /managing psychosocial triggers

High fibre diet may be helpful

Peptic Ulcer Disease

H2 blockers

Proton pump inhibitors

Abdominal migraine

Pizotifen may be effective as prophylaxis

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Nutritional support

Anti-inflammatory /immunomodulatory drugs

Prognosis

Most studies show that organic disease is rarely missed in children with chronic abdominal pain.

Thirty to fifty percent of children with chronic abdominal pain settle within 6 weeks with the rest

taking somewhat longer. Factors associated with a poorer prognosis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Prognostic Indicators in Children with Chronic Abdominal Pain

Factor

Better prognosis

Worse prognosis

Family

Gender

No family history of chronic pain

Girls

Family members with chronic pain

Boys

Age Of Onset

Older than 6 years

Younger than 6 years

Duration of pain before

Treatment

Less than 6 months

More than 6 months

Adults who as children had chronic abdominal pain are at increased risk of having functional

abdominal pain (as well as headaches and back pain) but in the vast majority of cases this does

not interfere with their daily activities.

ABDOMINAL PAIN, CHRONIC

Conclusion

Recurrent abdominal pain of childhood is a common condition of childhood. The vast number of

children with this condition do not have serious underlying gastro-intestinal disease and those that

do can be readily distinguished by clinical assessment and a few basic screening investigations.

References

Up to date; Evaluation of the child and adolescent with chronic abdominal pain. Last literature

review 19.1: January 2011-06-22. Contains details of Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional

gastrointestinal disorders at childhood (ages 4-18 years).

Clinical Report: New recommendations for treating children with chronic abdominal pain.

Subcommittee on Chronic Abdominal Pain of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics

March 2006

Cochrane database of systematic reviews has ongoing reviews of psychosocial, dietary and

pharmacological interventions.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Radionic Library 2014 PDFDocument27 pagesThe Radionic Library 2014 PDFnikko686867% (6)

- Thesis StatementsDocument4 pagesThesis StatementsJames DayritNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Intravenous Initiation ModuleDocument58 pagesPeripheral Intravenous Initiation ModuleJaney Co100% (1)

- Practice Test Medical Surgical Nursing 150 Items PDFDocument9 pagesPractice Test Medical Surgical Nursing 150 Items PDFPondang Reviewers BulacanNo ratings yet

- Section-F (5: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2010Document2 pagesSection-F (5: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2010BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Second M.B.B.S. Degree Examination, 2010 206. Microbiology - Ii 9 July)Document3 pagesSecond M.B.B.S. Degree Examination, 2010 206. Microbiology - Ii 9 July)BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-F: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2009Document1 pageSection-F: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2009BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-F 206. Microbiology-Ii (New Regulations) (Time: 3 HoursDocument2 pagesSection-F 206. Microbiology-Ii (New Regulations) (Time: 3 HoursBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-F 206. Microbiology-Ii (New Regulations) (Time: 3 HoursDocument2 pagesSection-F 206. Microbiology-Ii (New Regulations) (Time: 3 HoursBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- 4136 MCQDocument2 pages4136 MCQBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2012Document1 pageSecond M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2012BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2009Document1 pageSection-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2009BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2011 207. Forensic MedicineDocument3 pagesSecond M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2011 207. Forensic MedicineBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2008Document1 pageSection-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2008BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Section-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2010Document1 pageSection-B: Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2010BalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To AntennasDocument47 pagesIntroduction To AntennasBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Chapter No. Title Page NoDocument16 pagesChapter No. Title Page NoBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Defected Ground Structures in Designing Microstrip Filters WithDocument7 pagesThe Use of Defected Ground Structures in Designing Microstrip Filters WithBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Nerve LesionDocument11 pagesPeripheral Nerve LesionBalaKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of FastingDocument3 pagesBenefits of FastingThe Truth SeekerNo ratings yet

- Four Temperaments - WikipediaDocument9 pagesFour Temperaments - Wikipediaprince christopherNo ratings yet

- Chapter 66 - CDocument20 pagesChapter 66 - CTang Wai Foo0% (1)

- Tiebe Michael-Green, R.N.: 6 Blackburn Court Burtonsville, MD 20866Document4 pagesTiebe Michael-Green, R.N.: 6 Blackburn Court Burtonsville, MD 20866api-377789171No ratings yet

- Mentor Guide GSRG 062015Document10 pagesMentor Guide GSRG 062015api-290478033No ratings yet

- Final Business PlanDocument23 pagesFinal Business Planapi-283142068No ratings yet

- Points For Revision of PayDocument2 pagesPoints For Revision of Payeins_mptNo ratings yet

- Movement 11 - White Crane Spreads Wings - Proofread LN 2021-06-07Document4 pagesMovement 11 - White Crane Spreads Wings - Proofread LN 2021-06-07api-268467409No ratings yet

- Aviation Medicine and The Airline Passenger PDFDocument225 pagesAviation Medicine and The Airline Passenger PDFabhayNo ratings yet

- Asd Instruments Report PDFDocument30 pagesAsd Instruments Report PDFJovanka Solmosan100% (3)

- SeaCell Brochure en 20140826Document12 pagesSeaCell Brochure en 20140826Puneet SingalNo ratings yet

- Draft Case 2. Acne VulgarisDocument30 pagesDraft Case 2. Acne VulgarisVirgi AhmadNo ratings yet

- Apirl 2001 Paper 2 (CL)Document15 pagesApirl 2001 Paper 2 (CL)Aaron Wallace100% (1)

- Embolismo Pulmonar NejmDocument3 pagesEmbolismo Pulmonar NejmSaidNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Past History in Homœopathic PrescribingDocument11 pagesThe Significance of Past History in Homœopathic PrescribingClangames 4No ratings yet

- Sleep Intro and Physiology 81113Document30 pagesSleep Intro and Physiology 81113malchukNo ratings yet

- DRABCDocument19 pagesDRABCAzmi Khamis100% (1)

- CH 6 Part 1Document7 pagesCH 6 Part 1ArenNo ratings yet

- The Integumentary System: For Year 1 Generic Nursing Students By: Zelalem. ADocument48 pagesThe Integumentary System: For Year 1 Generic Nursing Students By: Zelalem. AAmanuel MaruNo ratings yet

- Pathway CKBDocument2 pagesPathway CKBFahrunnisa Al AzizahNo ratings yet

- Cell Nutrition GenesDocument24 pagesCell Nutrition GenesAlberto Alberto100% (3)

- Emergence Profile in Natural Tooth ContourDocument6 pagesEmergence Profile in Natural Tooth Contoursivak_198No ratings yet

- Agrochemical PoisoningDocument64 pagesAgrochemical PoisoningSuha AbdullahNo ratings yet

- USMLE Flashcards: Pathology - Side by SideDocument382 pagesUSMLE Flashcards: Pathology - Side by SideMedSchoolStuff100% (2)

- Animal Behaviour: Robert W. Elwood, Mirjam AppelDocument4 pagesAnimal Behaviour: Robert W. Elwood, Mirjam AppelputriaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Kwashior and MarasmusDocument17 pagesKwashior and Marasmuszuby_0302No ratings yet