Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Allergic Rhinitis

Uploaded by

Chay Alcantara0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views4 pagesOriginal Title

Allergic Rhinitis.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views4 pagesAllergic Rhinitis

Uploaded by

Chay AlcantaraCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis is defined by the presence of nasal congestion, anterior

and posterior rhinorrhea, sneezing, and nasal itching secondary to Ig-E

mediated reaction of the immune system to any allergens that trigger allergic

inflammation of the nasal mucosa.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) affects patients of all ages. It affects 10-30% of

children and adults in the United States, and a 20% overall prevalence in the

Philippines according to the 2008 National Nutrition and Health Survey

(Abong, et.al.). Mainly pollens cause seasonal allergic rhinitis and as such the

clinical symptoms appear within the pollen season. Perennial allergic rhinitis

is caused by chronic exposure to allergens (such as house dust, molds,

certain food) and as such incites a permanent inflammation of the nasal

mucosa.

Risk Factors for Allergic Rhinitis include family history of atopic

diseases, increased serum Ig-E and presence of allergen specific Ig-E, male

sex, firstborn status, early use of antibiotics, and exposure to indoor

allergens. Patients with allergic rhinitis are also found to have other

symptoms of allergic diseases, mainly atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, and

asthma. More than 40% of patients with AR have asthma, and more than 80%

of asthmatic patients have concomitant rhinitis. Other co-morbidities

associated with AR include sinusitis, nasal polyposis, upper respiratory tract

infections, and otitis media with effusion; sleep disorders, and impaired

learning and attention in children, among others.

Pathogenesis

The nose has a large mucosal surface area and entrapment of allergens

especially during symptomatic season where the mucosa is already swollen

and hyperemic, triggers submucosal edema with eosinophil infiltration, along

with some basophils and neutrophils. IgE released by plasma cells binds with

mast cells, which generate and release mediators that trigger histamine,

PGD, and leukotrienes, capable of producing tissue edema and eosinophilic

infiltration.

Allergic diseases of the upper airways are frequently inherited in

autosomal-dominant pattern that predisposes an affected person to produce

high levels of allergen-specific IgE. These antibodies crosslinks with allergens

on mast cell surface resulting in degranulation and mediator release that

stimulates blood vessels, nerves, glands causing the clinical manifestations.

Mast cell mediators include histamine, which reproduces all acute symptoms

such as mucus secretion, vasodilation thus nasal congestion, increased

vascular permeability thus tissue edema and sneezing through stimulation of

sensory nerve fibers. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes are produced by the

crosslinking of IgE antibodies on mast cells. Prostaglandin D2 appears to be

more potent than histamine and LTB4 is the most potent chemotactic factor.

Other mediators like bradykinins are vasoactive and platelet-activating factor

is also a potent chemotactic factor.

Immediate allergic response is observed within seconds to minutes of

allergen exposure, peaking at around 15-30 minutes. Sneezing correlates

with histamine influx, as well as presence of prostaglandin and tryptase

reflect the role of mast cells. Late-phase allergic reactions develop in half of

patients with seasonal rhinitis. The late phase reaction is associated with the

recurrence of mast cell mediator release coincident with cytokine production.

The late-phase reaction is also theorized to be related to the chronicity of

symptoms.

Symptoms

According to the Philippine Society of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and

Neck Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines for Allergic Rhinitis, the diagnosis of

Allergic Rhinitis is strongly considered in the presence of nasal itching,

sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion or obstruction, triggered by allergen

exposure. Supportive clinical information about frequency, duration, and

severity of symptoms; personal history of atopy manifestations; family history

of atopy; possible allergen identification; absence of symptoms upon change

in environment; previous allergy testing result; response to pharmacological

treatment and previous immunotherapy; must also be elicited. Anterior

rhinoscopy must be performed to support the diagnosis. Nasal endoscopy is

also strongly recommended for select patients. A complete ear, nose, and

throat examination must be performed on all patients with allergic rhinitis.

Detailed allergic work-up may also be performed for patients with

questionable diagnosis, unresponsive/intolerant to pharmacotherapy,

multiple target organ involvement, possible immunotherapy, or local allergic

rhinitis.

Local allergic rhinitis is a subset of patients where clinical history and

physical examination are consistent with allergic rhinitis but no evidence of

systemic atopy.

Treatment

Prevention is essential and individuals with allergic rhinitis are best

treated with less to nil exposure to allergen or triggers. Most patients though

would also require adjuvant pharmacotherapy as well.

Allergen avoidance measure would include humidity control, frequent

change of beddings, avoidance of carpeting, heavy curtains, clothed

upholstery, and the like. Use of dilute bleach solutions on nonporous surfaces

may reduce indoor fungal exposure.

Nasal saline irrigation may also serve as adjunctive treatment for

patients with allergic rhinitis. Moreover, systemic antihistamines are strongly

recommended for patients suffering from intermittent symptoms and short-

term allergen exposure. Alternative therapy for oral/systemic antihistamines

includes intranasal medications. Intranasal corticosteroids are more effective

than antihistamines for patients with moderate-severe, persistent symptoms,

and long-term allergen exposure. The duration of therapy can also be

individually based on patient follow-up findings. Anti-Leukotriene agents like

Montelukast can be given for patients with co-existing asthma. Cromolyn

sodium inhibits degradulation of sensitized mast cells thereby blocking

inflammatory and allergic mediator protein release, and though known for its

lesser side effects, it remains less effective than corticosteroids. Oral and

topical decongestants may be used by patients with prominent nasal

obstruction, but must be used judiciously. Allergen immunotherapy may

prevent new allergen sensitizations and reduce risk of progression of allergic

rhinitis to asthma.

Age-based Approach

Children less than 2 years of age, though uncommon to develop

allergic rhinitis, may benefit from Cromolyn sodium nasal spray and second-

generated antihistamines in liquid formulation. Pediatric patients with severe

symptoms that are unresponsive to either those previously mentioned,

glucocorticoid nasal spray may be administered.

Older children and adults with mild or episodic symptoms can be

managed with second-generation oral antihistamine, glucocorticoid nasal

spray, and cromolyn spray. Persistent or moderate to severe symptoms can

be best addressed with glucocorticoid nasal sprays.

Bibliography

Abong, J. (2012). Prevalence of Allergic Rhinitis in Filipino adults based on the

National Nutrition and Health Survey. Asia Pacific Allergy. Vol 2: pp. 129-

135

Clinical Practice Guidelines, PSO-HNS on Allergic Rhinitis in Adults. (2015).

Prepared by Philippine Academy of Rhinology.

de Shazo, R. and Kemp, S. (2016.) Allergic rhinitis: Clinical manifestations,

epidemiology, and diagnosis. UptoDate Wolters Kluver, retrieved 25 February

2017.

de Shazo, R. and Kemp, S. (2016.) Pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis (rhinosinusitis).

UptoDate Wolters Kluver, retrieved 25 February 2017.

de Shazo, R. and Kemp, S. (2016.) Pharmacotherapy of allergic rhinitis.

UptoDate Wolters Kluver, retrieved 25 February 2017.

Kasper, D.L. et al. (2015). Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 19 th

Edition. McGraw-Hill Education, USA.

Probst, R. et. al. (2006). Basic Otorhinolaryngology, A Step by Step Learning

Guide. Thieme, New York, USA.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Atypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive DisorderDocument13 pagesAtypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive DisorderrantiNo ratings yet

- Essential Oils in Nepal - A Practical Guide To Essential Oils and AromatherapyDocument6 pagesEssential Oils in Nepal - A Practical Guide To Essential Oils and Aromatherapykhilendragurung4859No ratings yet

- Aaron T Beck TranscriptDocument21 pagesAaron T Beck TranscriptcorsovaNo ratings yet

- Adverse Event Tracking Log: Subject Initials Subject ID# Page ofDocument1 pageAdverse Event Tracking Log: Subject Initials Subject ID# Page ofPratyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric BurnsDocument19 pagesPediatric BurnsmalindaNo ratings yet

- TB Case Finding (Slide)Document15 pagesTB Case Finding (Slide)Emman Acosta DomingcilNo ratings yet

- Hemophilia: Abid DesignsDocument13 pagesHemophilia: Abid DesignsSumati Gupta100% (1)

- Sample ChapteryyuDocument6 pagesSample ChapteryyuPrayitno SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Celsite, Surecan, Cytocan: Access Port Systems, Piccs, Accessories and Non-Coring Port NeedlesDocument36 pagesCelsite, Surecan, Cytocan: Access Port Systems, Piccs, Accessories and Non-Coring Port NeedlesmochkurniawanNo ratings yet

- COPD Case StudyDocument4 pagesCOPD Case StudyPj Declarador100% (4)

- Sciatica and Lumbar Radiculopathy Prolotherapy Treatments PDFDocument12 pagesSciatica and Lumbar Radiculopathy Prolotherapy Treatments PDFdannisanurmiyaNo ratings yet

- Hyperthermia SystemicDocument21 pagesHyperthermia Systemicataraix22No ratings yet

- Cord ProlapseDocument2 pagesCord ProlapseUsman Ali AkbarNo ratings yet

- Cosmogamma Brosur E-Catalog 2021Document18 pagesCosmogamma Brosur E-Catalog 2021binta.deniartikasariNo ratings yet

- Physical Disabilities: Use of Ipads by Occupational Therapists in A Medical Intensive Care UnitDocument4 pagesPhysical Disabilities: Use of Ipads by Occupational Therapists in A Medical Intensive Care Unitapi-241031382No ratings yet

- Functional Classification of Ventilator ModesDocument53 pagesFunctional Classification of Ventilator ModesNasrullah KhanNo ratings yet

- FiveSibes Live Gib Strong Tell Us About Your K9 Epileptic Survey ResultsDocument57 pagesFiveSibes Live Gib Strong Tell Us About Your K9 Epileptic Survey ResultsDorothy Wills-RafteryNo ratings yet

- 3B Scientific Therapy US 2017 PDFDocument212 pages3B Scientific Therapy US 2017 PDFhelen morenoNo ratings yet

- GENIOPLASTYDocument36 pagesGENIOPLASTYJesus MullinsNo ratings yet

- I.-NCP John Richmond LacadenDocument3 pagesI.-NCP John Richmond LacadenRichmond Lacaden100% (1)

- SOAP FormatDocument2 pagesSOAP FormatFarooq ShahNo ratings yet

- UNIT-5 Pharmacology of NeurosurgeryDocument12 pagesUNIT-5 Pharmacology of NeurosurgeryFaizan Mazhar100% (1)

- Soft Tissue InjuryDocument2 pagesSoft Tissue InjuryThiruNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorders of PregnancyDocument9 pagesHypertensive Disorders of PregnancyFcm-srAaf100% (1)

- Philippine Journal of Child Sexual AbuseDocument17 pagesPhilippine Journal of Child Sexual AbuseHector MasonNo ratings yet

- Bordeline Personality DisorderDocument6 pagesBordeline Personality DisorderWilliam Donato Rodriguez PacahualaNo ratings yet

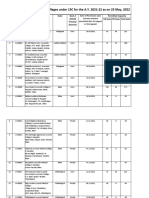

- List of Permitted Ayurveda Colleges For The A.Y. 2021-22 Till 06.05.2022Document52 pagesList of Permitted Ayurveda Colleges For The A.Y. 2021-22 Till 06.05.2022Re Ed EstNo ratings yet

- 3 Kuliah GERDDocument40 pages3 Kuliah GERDAnonymous vUEDx8No ratings yet

- Glaukoma - PPTX KoassDocument38 pagesGlaukoma - PPTX Koassdhita01No ratings yet

- The Radial Appliance and Wet Cell BatteryDocument160 pagesThe Radial Appliance and Wet Cell Batteryvanderwalt.paul2286No ratings yet