Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DR Ambedkar

Uploaded by

Sangram007Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DR Ambedkar

Uploaded by

Sangram007Copyright:

Available Formats

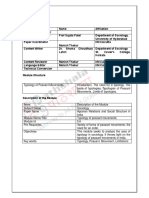

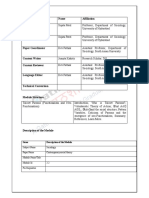

Input Template for Content Writers

(e-Text and Learn More)

1. Details of Module and its Structure

Module Detail

Subject Name Sociology

Paper Name Sociology of India

Module Name/Title Approaches to the study if Indian society

Module Id Non Brahmin Approach to the Study of Indian Society: Dr. B.R.

Ambedkar

Pre-requisites Basic knowledge of Indian history- colonial and post-colonial,

Bbasic knowledge of sociological concepts and terms. Anti-caste

movements

Objectives Understand Non Brahmin Approach of B.R Ambedkar and

understand caste as graded inequality.

Make students understand the linkages between knowledge and

power

To push students to be sensitive to the concept of Brahmanical

patriarchy.

Keywords Caste, Knowledge and Power, Graded Inequality, Identity,

Brahmanical Patriarchy, Identity, Conversion

Structure of Module / Syllabus of a module (Define Topic / Sub-topic of module)

Introduction Introduces the debate

Dr. B.R Ambedkars Analyse Ambedkars analysis of caste.

Analysis of Caste

Non-Brahmanical Ambedkars analysis of the subordination of women, referred to

Approach to the as the non-brahmanical approach to the question of womens

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

Question of Womens liberation in India,

Liberation

Dr. B.R Ambedkars Ambedkars strategies against untouchability and the caste

Strategies Against system.

Untouchability

2. 2. Development Team

Role Name Affiliation

National Coordinator

Subject Coordinator Sujata Patel Professor, Department of

Sociology, University of

Hyderabad

Paper Coordinator Anurekha Chari Wagh Assistant Professor,

Department of Sociology,

Savitribai Phule Pune

Univiersity

Content Writer/Author (CW) Anurekha Chari Wagh M.Phil Scholar, Department

of Sociology, Savitribai

Phule Pune University

Content Reviewer (CR) Anurekha Chari Wagh Assistant Professor,

Department of Sociology,

Savitribai Phule Pune

Univiersity

Language Editor (LE) Erika Mascarenas Senior English Teacher,

Kendriya Vidyalaya, Pune

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Dr. B.R Ambedkars Analysis of Caste

3. Non-Brahmanical Approach to the Question of Womens Liberation

4. Dr. B.R Ambedkars Strategies Against Untouchability

5. Conclusion

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

Non Brahmin Approach to the Study of Indian Society: Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

This module discusses Dr. B. R Ambedkars analysis of the study of Indian society, referred to as

non-Brahmin approach. This approach is based on the idea that linkages between knowledge

and power are real and its impacts are what get presented as reality/truth with regard to society.

The crucial question embedded within this perspective is How do we analyse India? This

approach is based on the argument that for a very long time India has been perceived within a

Hindu reality and identity, which does not bring into the discussion the principles of inequality,

injustice and hierarchy that Hinduism, as a religious principle, thought and practice has instituted.

So the approach, by offering an alternative perspective, posed an alternative to an understanding of

India. This approach is political as it exposes not only the politics behind knowledge construction

but also implicates the self who are in the processes of knowledge creation, consumption and

distribution. Further, this alternative demands for a change in the structures of inequality as

experienced by society. This perspective, built on ideologies of radical social thinkers such as

Phule, Ambedkar and Periyar, not only theorises on society but also calls for a change in it.

Their ideologies questioned the writings of officials and scholars who, while analysing what defines

India, drew heavily from a world view of Hinduism that privileged the Brahmins at the cost of the

non-brahmins. Such a Brahmanical production of knowledge was challenged by the marginal

voices who counter posed this hierarchical knowledge with an emancipatory perspective, which

brought out into the open the complexities and inequalities that defined the lives of a large number

of Indians. I quote Rege extensively here, she states that the colonialists and nationalists contested

the function of knowledge in colonial India, for both, the nature of knowledge about India was

essentially Hindu and brahmanical. After the Second World War social science discourses

refashioned the binaries of Orient/Occident through the tradition/modernity thesis or indigenous

approaches, both of which, glossing over the structural inequalities in Indian society, normalized

the idea of knowledge and education project offered in India, as Hindu and Brahmanical. Phule

and Ambedkar in different ways, by weaving together the emancipatory non-Vedic materialist

traditions (Lokayatta, Buddha, Kabir) and new Western ideas (Thomas Paine, John Dewey, Karl

Marx) had challenged the binaries of Western modernization and Indian tradition; private caste

and gender with public nation and sought to refashion modernity and thereby its project of

education( Rege 2010: 92-93).

Drawing upon the above arguments, one can clearly see how power works through production,

consumption and distribution of knowledge within particular contexts. This argument could explain

why it would be interesting to ask why sociologists in India did not draw upon the works of Phule,

Ambedkar and Periyar for such a long time. One can even stretch the argument to ask why it is that

in certain parts of India, one would find references to Phule and Ambedkar but not Periyar and vice

versa. This is a pertinent question of what is knowledge, and whose knowledge, not only within

mainstream dominant discourses but also of alternative discourses that challenge the mainstream

knowledge production. Kannbiran (2009:39) states that Ambedkar offered a multi layered, counter

hegemonic reading of caste that was lost on at least three generations of sociologists and accounts

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

for several conservative trends in social science. Kannbiran conceptualizes this in terms of silence

in sociological work1, which has a great impact on how sociologists have approached and analysed

caste.

Within academic discourse there have been many discussions with regard to its conceptualisation.

How does one refer to this position; perspective from below2 or non Brahmin approach?

Oommen (2001) states that perspective from below includes not only an analysis of the nature of

social structure such as caste, but also focuses on the location of the researcher within the

production of knowledge. It thus includes a politics of location of not only the social reality to be

analysed but also the location of the researcher that leads to a cognitive blackout of everyday life

experiences of Dalit Bahujans.

The module would have the following sections. Section one would analyse Ambedkars analysis of

caste. Section two would discuss Ambedkars analysis of the subordination of women, referred to as

the non-brahmanical approach to the question of womens liberation in India, and section three

would examine Ambedkars strategies against untouchability and the caste system.

Section One: Dr. B.R. Ambedkars Analysis of Caste3:

Dr. Ambedkar developed a theory of caste by analysing its origin and growth and the humiliating

processes of untouchability . He argued that in its classical form the caste system involved in itself

social, economic, cultural and political frameworks of governance of Hindu society. This form of

governance, based on caste which was exclusive to Hindu society, is hierarchical and unequal as it

divided the Hindu population into social groups called castes. Further, the castes are then made

endogamous, restricting marriage within the caste and in addition, assigned civil, cultural,

educational and economic rights, for each caste and continuance by heredity without freedom to

change. The entitlements of rights are not only unequal across the castes but it is also hierarchical-

rights going down from high caste to low caste. In this hierarchy some occupations or economic

activities are treated as superior and others as inferior. Furthermore, such hierarchy is maintained as

it is based on principles of purity and pollution/impurity. Caste also provides a mechanism for

enforcement of the system in terms of social ostracism, through a provision of social and economic

penalties, including social and economic boycott.

1

This reflects very close to life. I could see how, when I joined Masters of Sociology, University of Pune (1997-99) after

pursuing sociology as bachelors honours course, the only reference that I had with regard to Dr. B.R Ambedkar was

that he was the Father of the Indian Constitution. Neither did sociology training give me any insight to his analysis

nor did my location as a Tamilian Brahmin Upper caste-class woman help. To add to this neither did the masters

course in Department of Sociology, University of Pune have any reference to Ambedkar. Introduction to his ideas and

perspectives was through discussions with students and teachers and reading on social movement literature. It was

only in the academic year 2002-2003 that the ideas of Phule and Ambedkar were introduced in the syllabi.

2

Oommen (2001) makes a distinction between perspective from below and subaltern approach. He argues that the

context for the subaltern history was provided by colonial India and the freedom struggle. It referred to the national

historians as macro-holists who ignored the voices from below. Subalternists are micro-individualists who missed the

view from above.

3

Students are requested to refer to the Module on Indological Approach of G. S Ghurye and Structural Functional

Approach of M.N Srinivas and compare the ideas on caste with Ambedkars ideas on caste.

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

The question is why people followed this unequal and stigmatized system? Ambedkar argues that it

was difficult for people to question the inequality as the caste system drew justification from

elements of the Hindu religious philosophy, making it sacrilegious to question it. Castes are referred

to as a form having divine origin4 which makes it difficult to conceptually change the system.

Hindu philosophy provided divine justification for the origin and sustenance of the Hindu social

system especially to the doctrine of inequality in the social, cultural, economic and religious

spheres.

Especially its linkages with concepts of karma, (one should perform ones duty assigned to him by

his/her caste and birth and never question or challenge it) and rebirth (performance of ones karma

/duty in this present life would ensure a higher birth in the next life), kind of eroded any challenge.

It is so ironical that change was embedded in continuity; the more steadfast one is in the

performance of ones assigned karma or duty, the more it increases the chance of ensuring a better

life in the next birth. The system structured around the principle of fatalism was rationalized as an

outcome of ones deeds in the last life. So there was no chance of change and escape. Jaffrelot

(2009) argues that the lower castes were not in a position to question the inequality because they

had internalized the hierarchy and also because caste system was based on graded inequality.

What was this? The logic divides the dominated groups and thus prevents them from challenging

the system. Jaffrelot states in a society of graded inequality, the Bahujan Samaj is divided into

the lower castes (Shudras) and the Dalits, and the Shudras and the dalits themselves are divided

into many jatis (Jaffrelot 2009: 1-2).

The system is based on the hierarchical and graded entitlements of various rights to different castes

and the rights increase in ascending order from Untouchable to Brahmin. In this hierarchical

arrangement castes are artfully interlinked in such a manner that the rights and privileges of the

higher castes become the disabilities of the lower castes. Thus castes cannot exist in a single form

rather they exist as a plural number, interlinked to each other in unequal measures of social,

religious, and economic relations and rights. Thus isolation and exclusion of Untouchables is a

unique feature of the caste system- The Brahmins in this hierarchy are not only placed at the top but

are also considered superior social beings worthy of special entitlements, rights and privileges. At

the bottom, the Untouchables and lower castes are treated as sub-human beings or lesser beings

considered unworthy of any rights. The disabilities are so severe that they are physically and

socially isolated and excluded from the rest of the society. Isolation and exclusiveness makes them

anti-social and inimical to one another, so a development of collective consciousness is very

difficult to sustain and nurture.

The most pertinent principle of the caste system is the fixation of rights and continuance thereof by

hereditary. The caste social order gives multiple privileges and rights to the higher castes,

particularly the Brahmins. For example in the economic field every member must follow the

occupation assigned to each caste. It left no scope for individual capabilities, choices or

inclinations. Such a stratifiied system was based on the principle of no freedom to move'. Thus it

was not so much the existence of classes or segmentation but rather the idea of isolation and

4

Divine origin of caste system The centre of the Hindu philosophy is neither the society nor the

individual, it is a class- of supermen called Brahmins. The philosophy holds that to be right and good the act

must serve the interest of a class of a supermen, namely the Brahmins. Anything which serves the interest of

this class, is alone entitled to be called good. Thus the philosophy, teaches that what is good for one

particular class is the only thing treated as morally right and good.

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

exclusiveness, which was inimical to a free social order. Such a structure was based on unequal

entitlements of rights among castes and inequality in the distribution of these rights, where the

lower castes suffered the most. The way social and economic rights were assigned, there was no

possibility of social and economic improvement for the lower castes. The members were deprived

of the rights to choose occupation, acquire property, and receive education.

It important to understand the unique feature of exclusive privileges enjoyed by the Brahmins and

denial of the minimum rights to the lower castes, particularly to the Untouchables, in order to

understand the present day inter-caste economic inequality, particularly between Brahmins and

others. One could analyse the manner in which this inequality was expressed in the field of

education. Within education, the problem was denial of the right to education and opportunities to

develop human capabilities. Education was equaled to the study of the Vedas. All castes did not

have equal access to production, consumption and distribution of knowledge. Reading and writing

were the prerogative of the high castes and illiteracy, the destiny of the low castes. The teaching of

Vedas, officiating at a sacrifice, receiving grants and presents are the exclusive rights or

occupations of the Brahmins. There is no restriction on them to take up the other occupations of

other castes, except that of the Untouchables. The state did not hold itself responsible for opening

establishments for the study of arts and sciences that concerned the life of merchants and artisans.

Each caste managed to transmit the required know-how to its progeny in the traditional ways of

doing things. Brahmins, Kshatriyas and the Vaishyas could study Vedas but only the Brahmins had

the right to teach them. And in this structure Shudras were allowed neither to teach them nor study

them nor even hear them. Strong penalties were given to those who contravened these rules.

Illiteracy thus became an inherent part of the caste system by a process that was indirect but internal

to Hinduism, giving rise to illiteracy and ignorance.

Ambedkar in his analysis of the economic relations between high and lower castes Hindu social

order involves a slavish like character for the lower castes. The rule puts an interdict on the

economic independence of the deprived castes, which required them to serve others and constantly

remain economically dependent on the other castes. In the Hindu system of slavery, Shudras could

be made slaves of the three higher castes, but the higher castes could not be slaves of the Shudras.

Such an economic system was based on the method of exploitation rather than that of economic

efficiency. The manner in which rules concerning the right to property, occupation, employment,

wages, education, social status of occupation, dignity of labour, and rules governing graded slavery,

involved an element of economic exploitation, particularly of castes located at the bottom of the

caste hierarchy.

What are then the consequences of caste system? Ambedkar argues that exclusion and

discrimination are two most important consequences of the caste system. The unequal and

hierarchical assignment of civil, cultural, occupational, and property rights among castes implies

that although every caste, except those at the top of the caste order, suffer in varying magnitude

from an unequal division of social and economic rights. The Untouchables are excluded from

access to any economic rights except manual labour or service to the castes above them. Moreover,

they are prohibited from social intercourse and participation in several social and economic

activities due to the stigma of pollution associated with their caste. The caste system is not merely a

division of labour but also the division of the labourers into watertight compartments without any

opportunity for inter- occupational mobility. It was not only the division but also the accompanying

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

hierarchy in occupations, one graded above the other, which had lead to social and economic

gradation of labourers. Subordination of natural human powers and inclination to the necessity of

social rules and disassociation of intelligence from work and recreate contempt for physical labour.

Thus caste based economic order entails adverse consequences on economic growth and income

distribution. Furthermore, market failure associated with caste-based market discrimination not only

adversely affects economic growth, it also generated unequal income distribution and induced

poverty particularly among discriminated social groups.

Thus fixed and compulsary caste based division of occupation results in immobility of factors of

production and imperfections in the labour and market. Far from promoting competitive market

condition, caste-based division of labour and occupation creates:

Segmented and monopolistic market situations and produces less than economic optimum

Denial of equal rights

Exclusion

Discrimination

Subordination of one caste by the other

Untouchables suffer not only from denial of property rights but also human dignity

Teltumbe (2013) argues that Ambedkar had two important visions; one, annihilation of castes and

two, socialism within the economic structure based on enlightened middle class, featured by

emancipation of land and industrial capital. The final words of Ambedkar were educate, agitate

and organise; where he stressed the everchanging nature of reality and the need to be enlightened

enough to confront it. Educate so as to understand the world, agitate against evil and organize in

order to gain strength to root it out. Ambedkar perceived Hinduism as the emerging ground of the

caste system and thus argues for an alternative philosophy that would highlight the interlinkages

between caste and material bases of exploitation (Pardeshi 1998)

Section two: Non-Brahmanical Approach to the Question of Womens Liberation in India

Non-brahmanical approach interlinked hierarchies of caste, class and patriarchy to analyse the

question - why are women subordinate in the society? Parsdeshi (1998) argues that Ambedkars

analysis of caste helps one to explore the relation between caste and the subordination of women.

According to Ambedkar, the key to the caste system is not the idea of untouchability but that of the

principle of endogamy (rule that demands marriage only within ones group/caste). The fact of the

matter is that perpetuation of the system required strict rules governing marriage, so that boundaries

are not transgressed. The question that Ambedkar asked is -how did the system perpetuate

endogamy and thereby, the caste system? Ambedkar argued that it was through the rules and

practices governing the conduct, rights and obligations of women that the endogamy was continued

thereby strengthening caste. What were the rules? Pardeshi (1998) argues that Ambedkar referred to

four important practices enforced on women that maintained endogamy and thereby strengthened

caste, such as the practice of sati, enforced widowhood, enforced celibacy and the marriage of child

brides with older men and widowers. Through these practices womens sexuality was controlled

and regulated thereby ensuring the continuity of caste system. It is this context that Ambedkar refers

to women as the gateways of caste system.

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

In conceptualizing brahmanical patriarchy, Chakrvarthi (1993) argues that patriarchal codes ensure

that the caste system continues; where there are set rules and institutions by which caste and

gender are linked. Each shaping the other and where women are crucial in maintaining the

boundaries between castes and thus the Brahmanical codes for women differ according to the status

of the caste group in the hierarchy of castes with the most stringent control over sexuality. Within

this brahmanical patriarchy women of upper castes were especially the gateways- entry points into

caste system. The sexuality of the lower caste male was always perceived as a threat to upper caste

purity of blood, and so had to be institutionally prevented from having sexual access to women of

the higher castes. Thus women of the upper caste had to be carefully guarded and regulated. How

did the regulation take place? Chakravarthi argues that it was through the process of socialization,

where young girls were presented with binary visions of good/bad- girl, daughter, wife, mother

virtues of being pativrata (obedient and chaste to her husband), importance of virginity, following

and never questioning her husband were taught, accepted and perpetuated by women themselves.

Challenge to this principle was controlled by the right to discipline to keep women under control

was granted to kinsmen (moral policing)and the king (state) also had the power to discipline and

punish women for their errant behavior (Chakravarthi 1993).

How did the mixed marriages come to be regulated? Pardeshi (1998) argues that mixed marriges

were regulated by patriarchal and biased law. There are two kinds of mixed marriages Pratiloma

(hypogamy-marriage between women of higher caste and man of lower caste) and Anuloma

(hypergamy- marriage between men of higher caste and women of lower caste). Though both were

punished, the Pratiloma, marriage was not approved because in this case the women had

transgressed the boundaries, so punishment was excommunication. Here Omvedts (1994) analysis

adds to this complexity. She argues that there is very significant connection between the

illegitimacy of pratiloma and the legitimation of the devadasi5 tradition. She said that the temple

dancers enjoyed some amount of autonomy in the village. But these customs were used to

institutionalize the sexual accessibility of dalit women for the high caste men. Pardeshi (1998)

argues that one can observe a significant sexual dialectics, when the accessibility of dalit women to

the high caste men is juxtaposed with the forbiddance of relation between women of higher caste

and men of lower caste. This sexual dialectics informs caste interactions and behavior even in many

parts of India in the present times. Pardeshi (1998) argues that for Ambedkar , caste and patriarchy

intersect as a system to exploit women, but this system is not uniform but exploitation varies in

accordance with caste status. It is intensified as one moves down the caste hierarchy. Pardeshi states

that the exploitation of the dalit women is of a different nature than that of a high caste women.

Thus from within Phule-Ambedkarite position any claims to all women being a dalit is only a

rhetoric. To speak on behalf of all women is to deny the very core of Phule- Ambedkarism

(Pardeshi 1998:110). From the non-brahmanical position, the subordination of women in India is

structured through the intersections of caste, class and patriarchy.

Section Three: Ambedkars Strategies against Untouchability and the Caste System

5

Devadasi system is a religious practice that consists of offering young prepubescent girls to the deities in the Hindu

temples. The dedication usually requires the girl to become sexually available for community members. The girls

invariable belong to the lower castes/ Dalits and the community members are elite upper caste class men.

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

As mentioned in the introduction of this module Ambedkar had two important objectives first unite

Dalits and Bahujan Samaj and then to endow a separate identity that would help them to challenge

the sanskritisation process. Ambedkar implemented four strategies, which includes identity

building, electoral politics, working with the rulers, both British and the Congress and conversion to

challenge caste (Jaffrelot 2009).

Ambedkar by challenging the racial theory6 of caste hierarchy, argued that lower castes need to

develop an identity, (not caste based), to regain their self-respect and overcome their divisions. So

Ambedkar developed the identity of sons of the soil. Jaffrelot explains that Ambedkar in his

seminal book, The Untouchables, who were they and why they became Untouchables? (1948), he

argued that Untouchables were the descendants of the Broken Men7 and the original inhabitants of

India, before the conquest of the country by the Aryan invaders. According to Ambedkar these

Broken men followed the principles of Buddha and identified and continued being Buddhists,

despite many returning to the Hindu fold due to increased pressure from the Brahmins. According

to Ambedkar, the Broken Men hated the Brahmins, as they were perceived to be the enemies of

Buddhism and the Brahmins to deal with this imposed untouchability upon Broken Men as they

would not leave Buddhism. Thus what Ambedkar believed is that if the groups defined as

untouchables, recognized themselves as sons of the soil and Buddhists, they would be able to

transcend the differences of being divided into so many jatis and take a stand together as an ethnic

group against the system in its entirety (Ambedkar 1948, cited in Jaffrelot 2009).

The second strategy followed by Ambedkar according to Jaffrelot, was the instrument of electoral

politics. Jaffrelot argues that Ambedkar wanted the Dalits to develop into a political force and in

that was convinced that it would be important to pursue an election based strategy by creating a

political party, the Independent Labour Party in 1936. The party was not confined to addressing the

concerns of the Untouchables but that included the demands of the toiling labouring masses. The

ideology of the party was based on challenging Brahmanism and capitalism. But this party failed to

gain in the electoral process. Though it was a Dalit political party, the majority belonged to Mahar,

and very few other Dalit communities. As the ILP could not bring all the Dalits together, Ambedkar

resigned and formed the Scheduled Castes Federation (Dalit Federation in Marathi), arguing for a

minority status for the Scheduled Castes in 1942 (Jaffrelot 2009). The SCF depended mostly on

Ambedkar, but lost heavily as they had no organizational machinery, no network of party branches

and only a handful of party cadres and to this was added the immense popularity of the Congress,

who were the driving force of the freedom movement. Jaffrelot (2009) argues that the political

parties created by Ambedkar failed as a strategy, so through the formation of Republican Party of

India, he wanted to build a non-caste based political party.

6

G.S Ghurye, in his Caste and Race (1932) argued that caste was fundamentally the product of underlying racial

differences that are rationalized under conditions of continuing intercultural contact, assimilation and conflict.

7

Dr. Ambedkar argues that all primitive societies have been one day or the other conquered by invaders, who not

only raised themselves above the natives. These natives were then relegated to a peripheral group referred tom but

also as the Broken Men. When the conquerors became settled, these Broken Men started giving them services from

the attack of the native tribes who still remained nomadic. These Broken Men settled in the borders of the village

because of two reasons; one from the view of topography, it was logical for guards to be stationed at the border and

secondly the tribes did not accept the invaders/ foreigners of a different blood, within their groups (1948, cited in

Jaffrelot 2009: 2).

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

The third strategy was working with the ruling elite, both the British Rulers and later the Congress

government. Ambedkar pushed, coaxed and pressurized them to address the interests, concerns and

causes of Untouchables. Jaffrelot argues that Ambedkar had an ambivalent attitude towards the

British. On the one hand British represented rational government cherishing values of equality, with

whom, he could hope for a protection against the caste Hindus. On the other hand he resented the

British, who ruled a foreign country with force and violence, thereby challenging the values of

equality, freedom and brotherhood. But evaluating both the Congress and British, Ambedkar

strategically aligned with British, to gain maximum gains for the Untouchables. Later on he

accepted the position of Law minister in Independent Indias first government led by Nehru and

later on as the president of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution. For Ambedkar this was a

matter of strategy as he realized that it was easier to fight for the interests of the Scheduled Castes

from inside the government.

Jaffrelot (2009) argues that, it was through the efforts of Ambedkar that discrimination based on

religion, race, castes, sex and birth-place were dealt with by givingdue to Right to Equality, Article

15 and Article 17, that abolished Untouchability. When Ambedkar failed to bring in a uniform Civil

Code, to restructure the personal law, he tried to incorporate it within the Directive Principles of

State Policy, as The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout

the territory of India. Ambedkar then tried to legislate a reform of Hindu Personal Law, based on

the Hindu Code Bill that the British had evolved. What did the Hindu Code Bill propose? It had

provisions such as equality between men and women on question of property and adoption, granting

members of legal status to monogamous marriages only, the elimination of caste bar in the civil

marriage, petition for divorce by the wife. Such a radical change within the private lives of Hindus

was objected by many leaders from both the members of Hindu Mahasabha and the Congess.

Jaffrelot argues that though Nehru was attached to this bill, he did not have the courage to fight it

out in the assembly and so he did not support Ambedkar. The bill was passed after much of the

radical changes were changed into more tamed reforms. Due to this Ambedkar resigned from the

government. Though Ambedkar could secure some benefits for the Untouchables, he was

disillusioned with the political system as a strategy to bring about changes in the lives of the

Untouchables and believed it to be of limited use.

The final strategy used by Ambedkar was conversion. Jaffrelot argues that the idea of conversion to

another religion to escape caste was based on logically evaluating Hinduism. Based on analyzing

Ambedkars writings and speeches, Jaffrelot argues that the first instance that he referred to

conversion was in 1927. It was in 1935, that Ambedkar announced his decision to leave Hinduism

at the famous Yeola Conference. His famous words were, Unfortunately for me I was born a Hindu

Untouchable. It was beyond my power to prevent that, but, I declare that it is within my power to

refuse to live under ignoble and humiliating conditions. I solemnly assure you that I will not die a

Hindu (Bhagwan Das, 1969: 108, cited in Jaffrelot 2009: 12). Why Buddhism? For Ambedkar,

Buddhism formed the best possible choice because not only was it based on egalitarian principles

but also that it was born in India. The impact of conversion was varied for it was essentially the

Mahars, who converted and called themselves, Bauddha, but despite this they could not escape the

caste hierarchy. Jaffrelot states that not only did the Chambhars not convert to Buddhism but they

also opposed any concessions granted to the Bauddhas, through positive discrimination. To add to

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

this, many converted Bauddhas, continue to follow and observe some Hindu customs. For

Jaffrelot (2009), conversion by Ambedkar should not be perceived as strategy of last resort, but

instead, as an effort to endow the Untouchables with a new identity and a new sense of dignity.

Conclusion:

In this module one analysed the Non- Brahmanical approach to the study of India particularly the

perspective of Dr. Ambedkar. What are the important ideas that it raises? The approach strongly

argues that to understand India, one has to locate it within the complex terrain of caste, class and

patriarchy linkages which structure the life chances and opportunities of people. It raises

important questions about knowledge itself, such as what is knowledge?, and who creates

knowledge? It is important because sociology in India, has to answer the question raised by Kalpana

Kannabiran, why did sociologists in India fail to take cognizance of Ambedkars analysis of caste,

especially the conceptualization of caste as graded inequality? This is important because the

system was structured in such a manner that some groups were always below another group, which

made it extremely difficult to organize them together and unify them. Further by theorizing women

as gateways of caste system, Ambedkar powerfully stresses how the structures of caste continue

through the control and regulation of women and how women of different castes have different

experiences, thus questioning the universal category of Indian women.

Caste system was thus based on the principle of economic inequality and exploitation, where

economic and socio-cultural inequality was a direct outcome of its governing principles and its core

doctrine. We need to recognize that society in India is featured by cultural (language and ethnic)

heterogeneity, religious plurality and caste hierarchy. Non Brahmin approach is crucial as it seeks to

approach the study of India from the analysis of the everyday life of Dalit Bahujans. Such a

perspective presents a picture of a stratified, unequal, hierarchical and violent India. Further by

arguing the politics of knowledge production not only includes what social reality gets analysed but

also who analyses it and how the analysis takes place. The effort is to bring the marginalized

experiences right into the centre of what defines, structures and represents India.

Module : Approaches to the study if Indian society

Sociology

Paper : Sociology of India

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Codex Succubi - Second Edition - Final PDFDocument42 pagesCodex Succubi - Second Edition - Final PDFShih Li Kang88% (16)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Akan Ashanti Folk Tales R S RattrayDocument212 pagesAkan Ashanti Folk Tales R S RattraysambrefoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 3 Powerful Secrets To Uplift You in Love by Sami Wunder PDFDocument15 pages3 Powerful Secrets To Uplift You in Love by Sami Wunder PDFarati0% (1)

- Tiruppavai With MeaningDocument14 pagesTiruppavai With MeaningNeetha Raghu0% (3)

- Mothers Day's SermonDocument5 pagesMothers Day's SermonMylene Rochelle Manguiob Cruz100% (1)

- Mysteries From IndiaDocument13 pagesMysteries From IndiaHarsh MehtaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Islamic Family LawDocument53 pagesIntroduction To Islamic Family LawRifatNo ratings yet

- Theandros - Eschatology and Apokatastasis in Early Church FathersDocument6 pagesTheandros - Eschatology and Apokatastasis in Early Church FathersChris Ⓥ HuffNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Big Data Analytics and Its ImpactDocument12 pagesIntroduction to Big Data Analytics and Its ImpactSangram007No ratings yet

- Royal Navy used Biblical quotes for concise wartime messagingDocument2 pagesRoyal Navy used Biblical quotes for concise wartime messaginglydiapynkeNo ratings yet

- 12+Rules+to+Learn+to+Code+eBook+ (Updated+26 11 18)Document35 pages12+Rules+to+Learn+to+Code+eBook+ (Updated+26 11 18)MauricioNo ratings yet

- Safe homeopathic treatment for painful spinal stenosisDocument7 pagesSafe homeopathic treatment for painful spinal stenosisSangram007No ratings yet

- Women's Movement in India PDFDocument15 pagesWomen's Movement in India PDFSangram007100% (1)

- The Application of Urf in Islamic FinanceDocument17 pagesThe Application of Urf in Islamic Financehaliza amirah67% (3)

- Balkan HomeDocument344 pagesBalkan HomeMilan Ranđelović100% (1)

- Subanen HistoryDocument12 pagesSubanen HistoryRomeo Altaire Garcia100% (2)

- ASP 2015 Vol.25 Issue.2Document136 pagesASP 2015 Vol.25 Issue.2dtachaNo ratings yet

- Arvind Kejriwal Criminal Case Stay SoughtDocument10 pagesArvind Kejriwal Criminal Case Stay SoughtSangram007No ratings yet

- 6205 2014 33 1501 23716 Judgement 02-Sep-2020 PDFDocument60 pages6205 2014 33 1501 23716 Judgement 02-Sep-2020 PDFSangram007No ratings yet

- MR Arun Jaitley Vs Mr. Arvind Kejriwal & Ors On 26 July, 2017Document3 pagesMR Arun Jaitley Vs Mr. Arvind Kejriwal & Ors On 26 July, 2017Sangram007No ratings yet

- Evolution of Analytical Scalability and Big Data TechnologiesDocument11 pagesEvolution of Analytical Scalability and Big Data TechnologiesSangram007100% (1)

- Web Application Hosting in The AWS Cloud: Best PracticesDocument21 pagesWeb Application Hosting in The AWS Cloud: Best PracticesSangram007No ratings yet

- Arun Jaitley Vs Arvind Kejriwal On 12 December, 2017Document5 pagesArun Jaitley Vs Arvind Kejriwal On 12 December, 2017Sangram007No ratings yet

- Bombay High Court: Miss Kamalini Manmade Vs Union of India (Uoi) On 19 November, 1965Document11 pagesBombay High Court: Miss Kamalini Manmade Vs Union of India (Uoi) On 19 November, 1965Sangram007No ratings yet

- Aws Web Hosting Best PracticesDocument22 pagesAws Web Hosting Best PracticesSatyam Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Central Government Act Allows Secondary Evidence for DocumentsDocument1 pageCentral Government Act Allows Secondary Evidence for DocumentsSangram007No ratings yet

- B. Sumat Prasad Jain, Advocate Vs Sheo Dutt Sharma CR DefamationDocument12 pagesB. Sumat Prasad Jain, Advocate Vs Sheo Dutt Sharma CR DefamationSangram007No ratings yet

- Big Data Approach To Analytics & Web - The Actual Big DataDocument11 pagesBig Data Approach To Analytics & Web - The Actual Big DataSangram007No ratings yet

- Keywords: typology, peasant, movement, limitationsDocument12 pagesKeywords: typology, peasant, movement, limitationsSangram007100% (1)

- Dalit Movement and Backward Class Assertions in India PDFDocument14 pagesDalit Movement and Backward Class Assertions in India PDFSangram007100% (1)

- Indological and Oriental ApproachDocument15 pagesIndological and Oriental ApproachSangram007No ratings yet

- Virta Clinic 10-Week OutcomesDocument14 pagesVirta Clinic 10-Week OutcomesSangram007No ratings yet

- Agrarian Structure On The Eve of The British Rule IDocument9 pagesAgrarian Structure On The Eve of The British Rule ISangram007No ratings yet

- Dalit Movement and Backward Class Assertions in IndiaDocument14 pagesDalit Movement and Backward Class Assertions in IndiaSangram007No ratings yet

- Casteism, Anti-Brahmin Movements and Their Impact on Indian PoliticsDocument16 pagesCasteism, Anti-Brahmin Movements and Their Impact on Indian PoliticsSangram007No ratings yet

- Casteism, Anti-Brahmin Movements and Their Impact on Indian PoliticsDocument16 pagesCasteism, Anti-Brahmin Movements and Their Impact on Indian PoliticsSangram007No ratings yet

- Understanding Robert King Merton's Contributions to Functionalism and System AnalysisDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Robert King Merton's Contributions to Functionalism and System AnalysisSangram007No ratings yet

- Final Final GhuryeDocument17 pagesFinal Final GhuryeSangram007No ratings yet

- Right To Information Act, India: AnalysisDocument8 pagesRight To Information Act, India: AnalysisSangram007No ratings yet

- Talcott Parsons' Theory of Functionalism and Neo-FunctionalismDocument11 pagesTalcott Parsons' Theory of Functionalism and Neo-FunctionalismSangram007No ratings yet

- Family, Marriage and HouseholdDocument16 pagesFamily, Marriage and HouseholdSangram007100% (1)

- Culture of IndiaDocument44 pagesCulture of IndiaSangram007No ratings yet

- Depiction of Women in Selected Chapter Books for Children in IndiaDocument70 pagesDepiction of Women in Selected Chapter Books for Children in Indiai'm popaiNo ratings yet

- 1989 Issue 8 - The Bible On Large Families - Counsel of ChalcedonDocument2 pages1989 Issue 8 - The Bible On Large Families - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNo ratings yet

- September 2007 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomDocument15 pagesSeptember 2007 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomTemple Ohabei ShalomNo ratings yet

- Unbelievers Are Void of The SpiritDocument5 pagesUnbelievers Are Void of The SpiritGrace Church ModestoNo ratings yet

- The Divine Image ADivine ImageDocument12 pagesThe Divine Image ADivine ImageRani JeeNo ratings yet

- Love Letter From God To YouDocument3 pagesLove Letter From God To YouyetanothernameNo ratings yet

- Sotoba Komachi WaleyDocument15 pagesSotoba Komachi WaleyNebojša Pop-TasićNo ratings yet

- Jean Deauvignaud The Festive SpiritDocument52 pagesJean Deauvignaud The Festive Spirittomasmj1No ratings yet

- Islamic Cultural Center, Hyderabad (Proposed Project in Telangna)Document47 pagesIslamic Cultural Center, Hyderabad (Proposed Project in Telangna)Leela KrishnaNo ratings yet

- YouthDocument74 pagesYouthAnonymous MdfCUilNo ratings yet

- Newman on Christianity and Medical ScienceDocument8 pagesNewman on Christianity and Medical ScienceImsu AtuNo ratings yet

- 19-Arid-2248, Sidra Zamir (A), Pakistan Studies Final PaperDocument9 pages19-Arid-2248, Sidra Zamir (A), Pakistan Studies Final Paperhely shah100% (1)

- Josef Strzygowski - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesJosef Strzygowski - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaWolf MoonNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism On Plato and AristotleDocument1 pageLiterary Criticism On Plato and AristotleRoza Puspita100% (1)

- Shri Ramcharitmanas Sunderkand (English Meaning) - Ek-AUMDocument52 pagesShri Ramcharitmanas Sunderkand (English Meaning) - Ek-AUMswaminathan150% (2)

- CHAPTER 1: Understanding Quality and Total Quality Management from an Islamic PerspectiveDocument38 pagesCHAPTER 1: Understanding Quality and Total Quality Management from an Islamic PerspectiveAqilah RuslanNo ratings yet

- Sri Yantra For Learning, Wisdom, Creativity, Finance, Beauty, Spiritual EnrichmentDocument3 pagesSri Yantra For Learning, Wisdom, Creativity, Finance, Beauty, Spiritual EnrichmentGiredhar VenkataNo ratings yet