Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Quality Improvement Collaborative To Improve The Discharge Process For Hospitalized Children

Uploaded by

Rahimi BaharOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Quality Improvement Collaborative To Improve The Discharge Process For Hospitalized Children

Uploaded by

Rahimi BaharCopyright:

Available Formats

A Quality Improvement Collaborative

to Improve the Discharge Process

for Hospitalized Children

Susan Wu, MD,a,b Amy Tyler, MD,c,d Tina Logsdon, MS,e Nicholas M. Holmes, MD, MBA,f,g Ara Balkian, MD, MBA,a,b

Mark Brittan, MD, MPH,c,d LaVonda Hoover, BSN, CPN, MS,b Sara Martin, RN, BSN,d Melisa Paradis, MSN, RN, CPN,h

Rhonda Sparr-Perkins, RN, MBA,g Teresa Stanley, DNP, RN,i Rachel Weber, MSIE,g Michele Saysana, MDi, j

OBJECTIVE: To assess the impact of a quality improvement collaborative on abstract

quality and efficiency of pediatric discharges.

METHODS: This was a multicenter quality improvement collaborative including

11 tertiary-care freestanding childrens hospitals in the United States,

conducted between November 1, 2011 and October 31, 2012. Sites selected

interventions from a change package developed by an expert panel. Multiple

plandostudyact cycles were conducted on patient populations selected

aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Southern

by each site. Data on discharge-related care failures, family readiness for

California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California;

discharge, and 72-hour and 30-day readmissions were reported monthly bChildrens Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California;

cDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of

by each site. Surveys of each site were also conducted to evaluate the use of

Medicine, Denver, Colorado; dChildrens Hospital Colorado,

various change strategies. Aurora, Colorado; eChildrens Hospital Association,

Overland Park, Kansas; fDepartment of Surgery, Division

RESULTS: Most sites addressed discharge planning, quality of discharge

of Urology, University of California San Diego, San Diego,

instructions, and providing postdischarge support by phone. There was California; gRady Childrens Hospital San Diego, San

a significant decrease in discharge-related care failures, from 34% in the Diego, California; hChildrens Hospital & Medical Center,

Omaha, Nebraska; iRiley Hospital for Children at Indiana

first project quarter to 21% at the end of the collaborative (P < .05). There University Health, Indianapolis, Indiana; and jDepartment

was also a significant improvement in family perception of readiness for of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine,

Indianapolis, Indiana

discharge, from 85% of families reporting the highest rating to 91%

(P < .05). There was no improvement in unplanned 72-hour (0.7% vs 1.1%, Dr Wu conceptualized and designed the study,

participated in data collection, assisted in data

P = .29) and slight worsening of the 30-day readmission rate (4.5% vs 6.3%, analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and

P = .05). critically reviewed and revised the manuscript;

Drs Tyler, Brittan, and Saysana and Ms Hoover,

CONCLUSIONS: Institutions that participated in the collaborative had lower

Ms Martin, and Ms Stanley conceptualized and

rates of discharge-related care failures and improved family readiness designed the study, participated in data collection,

for discharge. There was no significant improvement in unplanned drafted the initial manuscript, and critically

readmissions. More studies are needed to evaluate which interventions are reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Logsdon

conceptualized and designed the study, supervised

most effective and to assess feasibility in nonchildrens hospital settings. data collection and analysis, drafted the initial

manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised

the manuscript; Dr Holmes conceptualized and

designed the study, participated in development of

Although discharge from the hospital In 1 adult study, as many as 49% of data collection instruments, and drafted the initial

for many pediatric patients means the patients had 1 medication error at manuscript; Dr Balkian, Ms Paradis, and Ms Sparr-

child is clinically improving, it also discharge, which could increase their Perkins conceptualized and designed the study,

likelihood for readmission.5 In other participated in data collection, and drafted the

creates potential risk because of the

initial manuscript; Ms Weber conceptualized and

transition of care.1 At a minimum this studies, 10% to 20% of patients had designed the study, participated in development of

care may include medications and an adverse event after discharge, with data collection instruments, participated in data

follow-up appointments, but it may about half of these events deemed to

also include home care, wound care, be preventable.6,7 To cite: Wu S, Tyler A, Logsdon T, et al. A Quality

or therapy. The discharge process Improvement Collaborative to Improve the

Discharge Process for Hospitalized Children.

has historically been fragmented Most of the work on improving

Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20143604

and variable, leading to errors.24 discharge processes to date has

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

PEDIATRICS Volume 138, number 2, August 2016:e20143604 QUALITY REPORT

focused on the adult population. TABLE 1 Participating Hospitals and Areas of Project Focus

Examples of these projects include Site Target Patient Population

the Better Outcomes for Older Adults Nationwide Childrens Hospital, Columbus, OH Patients with sickle cell disease readmitted within

Through Safe Transitions Project, 30 d for acute chest pain or pain crisis

sponsored by the Society for Hospital Childrens Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO Patients with asthma and seizure managed by

Medicine; Project Re-Engineered hospitalists

Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Unit-based patients on 7W managed by

Discharge, sponsored by the Agency

Health, Indianapolis, IN hospitalists, complex care patients on 8E

for Healthcare Research and Quality, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA Medical/surgical unit, cystic brosis admissions

National Heart, Lung and Blood and cardiovascular acute unit

Institute, Blue Cross Blue Shield New YorkPresbyterian Morgan Stanley Childrens NICU and oncologybone marrow transplant

Foundation, and the Patient-Centered Hospital, New York, NY

Childrens Hospital & Medical Center, Omaha, NE Nonchronic patients on medical/surgical unit

Outcomes Research Institute; and

Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Patients scheduled for discharge on medical and

the State Action on Avoidable Pittsburgh, PA surgical unit

Rehospitalizations initiative of The Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, All patients scheduled for discharge

the Commonwealth Fund and the PA

Institute for Healthcare Improvement Rady Childrens Hospital San Diego, San Diego, CA Patients with asthma on medical unit,

appendectomy on surgical unit, cardiac surgery

(IHI). All these projects recommend

in critical care unit, all patients on hematology/

strategies to improve the discharge oncology, and all patients in NICU

process, including scheduling Childrens National Medical Center, Washington, DC Medical patients managed by resident trainees

follow-up appointments before and hospitalists

discharge, medication plans, written

patient discharge instructions,

in pediatric patients was 6.5%, which participated in the collaborative.

patient education about diagnosis

is much lower than in adults. Recent One hospital did not submit data

and medications, follow-up telephone

publications have reported that most on interventions and therefore was

calls to the patient, communication

children who were readmitted had an excluded from analysis. All hospitals

to the outpatient primary provider

underlying chronic disease, and only were tertiary-care freestanding

at discharge, and others.811 Recently

a small percentage of readmissions childrens hospitals in the United

White et al12 improved discharge

were found to be preventable.17,18 States that were members of the

efficiency in a childrens hospital by

Interestingly, 1 study suggested that CHA. A specified target population

creating a common set of discharge

children who had a documented was selected at the discretion of

goals for 11 different pediatric

follow-up scheduled with their the participating site (Table 1). The

diseases. Although this intervention

primary care provider were more participants selected populations by

did decrease the length of stay, the

likely to be readmitted to the hospital specific disease processes, level of

readmission rate was not changed.

than those who did not.19 clinical complexity, or specific units

To date, the only published pediatric

in the hospital.

discharge improvement collaborative Because of the potential for errors

focused on improving communication and variability in the discharge

Intervention

to primary care providers after process, Childrens Hospital

hospital discharge.13 Association (CHA) formed the first The study was patterned after the

pediatric improvement collaborative standard methods used by the CHA

About 20% of older Medicare to examine whether shared in many of its other collaborative

patients who are hospitalized are improvement strategies would affect projects.2024 The model for this

readmitted to the hospital within 30 discharge-related care failures, improvement process was based

days after discharge.14 Because of parent-reported readiness for on previous work developed by

the high cost of readmissions, adult discharge, and readmission. the IHI and has been used

hospitals with high readmission rates successfully in pediatric settings.2529

receive reduced Medicare payments A multidisciplinary advisory panel

under the Affordable Care Act.15 METHODS of experts with previous experience

Reimbursement rate penalties for in discharge processes was recruited

Setting

Medicaid patients, including children, from across the CHA. The panel

are already being implemented The CHA invited its members evaluated the existing literature

in some states. In an analysis of to participate in a multicenter and adopted tools and change

>550000 pediatric admissions in 72 collaborative project addressing concepts from previous discharge

hospitals, Berry et al16 found that the the discharge process for pediatric programs.2,3,811,30 They also

30-day unplanned readmission rate inpatients. Eleven hospitals incorporated lessons learned

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

e2 WU et al

from previous CHA collaboratives, components of the measure included steps. In addition to collecting project

including the Improving Inpatient understanding of diagnosis, receiving measures, CHA staff scored each

Throughput and Improving Patient discharge instructions, receiving site based on improvement activity

Handoffs programs.20 This panel discharge education, compliance and performance by using the IHI

developed a change package covering with instructions, receiving Assessment Scale for Collaboratives.

6 broad areas, which included the necessary equipment, having a The scale rates teams between 0.5

following strategies: plan to follow up pending tests, and 5.0, with 0.5 defined as being

receiving help with appointments, signed up to participate and 5.0

Proactive discharge planning

and not needing a related unplanned demonstrating major change in all

throughout the hospitalization.

visit. A discharge phone call script areas, outcome measures at national

Improve throughput. adapted by the expert panel from benchmark levels, and spread under

Arrange postdischarge treatment. Project Re-Engineered Discharge way. (See Supplemental Table 7 for

was provided, and each site was rating scale.)31

Communicate postdischarge plan permitted to modify the script to

to providers. meet their local needs and capacity.10 Data Analysis

Communicate postdischarge plan Measures were plotted on run charts

to patients and families. All other measures were (Minitab version 17.1, State College,

Postdischarge support. optional and selected by the PA), with the first 3 months of data

individual sites depending on reported used as baseline. Only

Sites formed multidisciplinary the change strategies targeted months where 3 sites reported

teams and were required to (see Supplemental Information data were included. Run charts were

have an executive-level sponsor. and Supplemental Tables 16 for interpreted according to standard

The collaborative held 4 virtual definition of measures). Readiness probability-based rules for level

learning sessions and monthly Web for discharge and readmission P < .05.32,33 Data for both individual

conferences. In between the learning rates were priority measures hospital and overall hospital were

sessions were 3 action periods, and were highly recommended also aggregated to the quarterly level

during which each site performed although not required. Patient for analysis in SAS version 9.3 (SAS

small tests of change using the plan and family readiness for discharge Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Comparisons

dostudyact method. During the was defined as the percentage of between the entire baseline period

learning sessions, training on quality families rating the highest category and postbaseline values for the

improvement methods was provided on the hospitals standard patient aggregated hospital data were

by national experts. High performers satisfaction survey. Readmission at made with 2 tests. Within each

also shared their successes, and 72 hours and 30 days was defined quarter, first observation carried

participants were given opportunities as unplanned rehospitalization for forward or last observation carried

to ask questions. Sites also presented the same diagnosis. Baseline data back imputation was conducted for

their progress and challenges during were collected from August through missing data in SAS.

monthly Web conferences. Teams October 2011 if available. If baseline

could communicate with each other data were not available (eg, outreach This study was determined to be

and share tools and resources via calls), the first 3 months of project exempt by the Childrens Hospital Los

an electronic mailing list and a data were used as baseline. From Angeles Institutional Review Board

shared Web site. Teams were guided November 2011 to October 2012, (CHLA-14-00111).

through improvement efforts by an the hospitals participated by using

experienced improvement coach. Demings plandostudyact cycles to

RESULTS

perform tests of change, implement

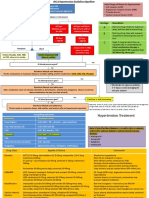

Measures and Data Collection improvements, and sustain results. Elements of the collaborative change

The primary aim of the study was Each site selected changes based package were adopted by each

to reduce discharge-related care on local capabilities and priorities. institution at varying levels (Table 2).

failures by 50% in 12 months. Standardized reporting of data All sites chose to work on educating

Discharge-related care failures were occurred on a monthly basis via an families on diagnosis and plans for

measured by using phone calls to electronic data repository managed discharge. Several sites also used

families 2 to 7 days after discharge. by The CHA and did not include discharge checklists, with discharge

Failure was a composite all-or-none any patient identifiers. Monthly milestones and barriers. Eight out

measure; if any problem related to reports also included a narrative of 10 sites improved the written

discharge occurred, the discharge section that included information discharge instructions given to

was counted as a failure. Required on successes, challenges, and next families. Some of these improvements

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

PEDIATRICS Volume 138, number 2, August 2016 e3

TABLE 2 Change Strategies Used by Participating Sites

Change Strategy Change Ideas Number of Sites Using Strategy

Proactive discharge planning throughout Educate the patient and family about diagnosis and plans for discharge. 10

hospitalization. Include discharge planning in rounds and other staff communication. 7

Establish and continuously update anticipated discharge date and time. 4

Ensure nancial problems will not impede discharge. 3

Improve throughput. Complete the discharge process promptly. 7

Create specic conditional or contingency discharge orders. 7

Proactively prevent and manage delays. 5

Work with essential partners (eg, laboratory, radiology, social work). 4

Spread discharges across the day. 3

Arrange for postdischarge treatment. Identify the correct medicines and a plan to obtain and take them. 9

Make appointments for follow-up medical appointments and postdischarge 7

tests.

Organize postdischarge home-based services and medical equipment. 6

Plan for the follow-up of results from laboratory tests or studies that are 3

pending at discharge.

Anticipate planned readmissions for additional treatment (eg, chemotherapy 2

treatments).

Communicate postdischarge plans to Transmit discharge summary to clinicians accepting care of the patient. 5

providers. Develop physician discharge summary for next providers. 4

Initiate verbal communication with outpatient caregivers as needed. 2

Communicate postdischarge plans to Create or improve written discharge instructions for the patient and family. 8

patients and families. Review the written discharge instructions with the patient and family. 6

Review with the patient and family what to do if a problem arises. 6

Postdischarge support. Provide telephone reinforcement of the discharge plan via outreach calls. 9

Provide opportunities for patients and families to ask questions after 4

discharge.

included designing standardized with 9 postintervention points below diagnosis, at 72 hours (Fig 3A) and

discharge instructions for certain the baseline mean and the final at 30 days (Fig 3B). Four hospitals

diagnoses, making instructions more postintervention point below the reported both rates. There was no

user-friendly, and creating new lower control limit. The aggregate improvement in unplanned 72-hour

discharge instruction forms in the rate of care failures was overall 34% (0.7% vs 1.1%, P = .29) and slight

electronic medical record. Almost all in the first project quarter; the rate at worsening of the 30-day readmission

sites (9 of 10) used postdischarge the end of the collaborative was 21%, rate (4.5% vs 6.3%, P = .05).

follow-up phone calls to reinforce or a reduction of 40% (P < .05). Top-

Of the 11 participating sites, 4

discharge instructions. Most sites also performing hospitals were able to

achieved an IHI Assessment Scale

reported working on identifying and achieve even lower care failure rates

for Collaboratives score of 5.0

obtaining discharge medications. Few with the use of varying interventions

at the end of the collaborative

sites addressed communication with (Fig 1B).

(Hospitals A, B, C, D), indicating

primary care providers.

Only 4 hospitals reported data on outstanding improvement. One site

Aggregate data for all hospitals family feeling ready for discharge obtained a score of 4.5 (sustainable

combined are depicted in monthly (Fig 2). For these hospitals, there improvement, Hospital E), and 4

run charts. Run charts with individual was a statistically significant sites achieved a 4.0 (significant

hospital trends are available online increase in the percentage of improvement, Hospitals F, G, H, I).

(Supplemental Figures 48). patients who rated the readiness for Two sites were able to test

Eight hospitals reported rates of discharge in the highest category. changes but did not demonstrate

discharge-related care failures. The precollaborative baseline was measurable improvement. Common

Because precollaborative data 85% of patients giving the highest characteristics of the sites that

were not available at most sites, rating; during the last quarter of the achieved a score of 5.0 included

the first quarter of the project was collaborative it was 91% (P < .05). strong multidisciplinary involvement;

used as baseline data. The run The run chart showed a shift of 6 close collaboration with electronic

chart demonstrated a shift, with 10 points above the median line in the medical record (EMR) teams;

consecutive points below the baseline last 2 quarters. dedicated staff time for discharge

median line (Supplemental Figure 4). phone calls, discharge education,

The statistical process control chart Five hospitals reported unplanned and discharge rounding; and use of

(Fig 1B) also confirms this finding, readmission rates for the same discharge checklists.

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

e4 WU et al

DISCUSSION

Adverse events related to poor

hospital discharge planning are well

described,34 and to our knowledge

this is the first multicenter

collaborative to target the hospital

discharge process for pediatric

inpatients. Because the discharge

process is complex, involving

multiple clinical microsystems,

achieving large-scale change is

particularly challenging. Although the

collaborative did not meet its target

of 50% reduction in care failures,

significant progress was made. We

found a decrease in discharge care

failures and improvement in patient

readiness for discharge. However,

there was no impact on 72-hour

unplanned readmissions and even

a slight increase in the 30-day

readmission rate.

A wide variety of change strategies

were adopted by the participating

sites to achieve results. One of the

most commonly adopted strategies

was proactive discharge planning

throughout the hospitalization.

Several change ideas were used to

accomplish this planning, such as

educating the patient and family

about diagnosis and plans for

discharge, including discharge

planning in rounds, establishing and

continuously updating anticipated

discharge time, and ensuring that

financial problems did not impede

discharge. Other key change areas

were improving communication

of postdischarge plans to families

and providing postdischarge

support via outreach phone calls.

Previous studies have shown that FIGURE 1

postdischarge contacts via home Discharge-related care failures (n = 8 sites reporting; 5895 discharges). Percentage of discharges

visits or follow-up phone calls were where 1 discharge-related care failure was identied during postdischarge phone call. First 3

months of available data used as baseline. A, Statistical process control p-chart. B, Annotated run

effective in decreasing health care chart, top-performing hospitals. Horizontal line represents the hospitals baseline from the rst 3

utilization and improving satisfaction months of data collection. LCL, lower condence level (3 standard deviations below the mean); NP,

with care.3538 Although most sites nurse practitioner; RN, registered nurse; UCL, upper condence level (3 standard deviations above

the mean).

made postdischarge phone calls

during the collaborative period, not

all were able to continue doing so. depending on the patient. If shortened it significantly. Follow-up

The standardized phone call script interpretation was needed, the call studies must be done to evaluate

used during the collaborative could could take even longer. Some sites the cost and benefit of phone calls to

take <5 minutes to 20 minutes, found this script unworkable and support their sustainability. Few sites

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

PEDIATRICS Volume 138, number 2, August 2016 e5

chose to implement interventions

related to communication and

coordination with outpatient

primary care physicians. Future

efforts focused on this strategy may

demonstrate more improvements in

discharge-related outcomes.

Despite improvements in discharge-

related outcome measures, there

was no improvement in readmission

rates during the collaborative. In

fact, we saw a slight increase in

30-day unplanned readmissions.

This could result from seasonal

variability in readmissions. Also,

readmission rates vary by diagnosis,

leading to high variability in this

measure. For example, 1 site focused

FIGURE 2

on management of patients with Proportion of families who felt ready for discharge (n = 4 sites reporting; 2824 discharges).

sickle cell disease, who have 30-day Percentage of families giving the highest rating of readiness for discharge on hospital patient

readmission rates between 10% satisfaction surveys.

and 20%, and another site focused

on patients with asthma, with much evidence that readmissions may a bundle of several strategies

lower readmission rates of <2%.3941 not be a good indicator of hospital simultaneously. Randomization

Also, our method was able to assess quality in the pediatric setting.44 of the interventions across

only revisits to the same facility.42 Readmission rates are not solely an sites would have increased our

Another possibility is that improving indicator of discharge quality; they ability to draw conclusions about

throughput and discharge timeliness are a measure of the entire health the effectiveness of individual

led to earlier discharge, with the system, as well as socioeconomic interventions but would not

unintended consequence of factors and patient disease.38,45,46 have allowed sites to choose the

increased readmission; however, There is also no consensus on the strategies most relevant to their

we did not collect data on length optimal readmission interval. The populations and feasible in their

of stay. There is also significant Centers for Medicare and Medicaid local environments. Third, for most

variability in the definition Services uses 30 days for adult measures sites did not have baseline

of readmissions. We defined readmissions measures; however, data before implementing changes.

readmissions as unplanned some studies have used 7, 14, or In addition, charts had only 11 to 15

readmissions for the same condition; 15 days. Future studies should data points, with the first 3 points

however, even within these establish standardized frameworks serving as baseline, leaving only

parameters, each site used different and measures for evaluating 8 to 12 postintervention points.

methods to collect the discharge care quality.47,48 Therefore, we had insufficient points

data. Even unplanned readmission to accurately calculate control limits.

may be unavoidable and therefore The limitations of this collaborative Also, because prestudy baseline

an insensitive measure for discharge are consistent with other initiatives data were not available for most

quality. The 3M Potentially to improve care across multiple measures, it is possible that the teams

Preventable Readmissions algorithm sites.49,50 First, the participating sites may have made early improvements

is a promising tool that can be were all tertiary-care freestanding that were not reflected in the

used in future improvement childrens hospitals, so the results data. This discrepancy is likely

efforts, but it has not yet been may not be generalizable to to underestimate the true effect

prospectively evaluated and may community hospitals or pediatric of the project. Nearly every site

still overestimate preventability.43 care provided in general hospitals. had difficulty obtaining data, and

Average unplanned readmission Second, we were not able to measure some sites were ultimately not

rates were very low in the population the impact of specific change able to submit data on some of the

studied: <1% for 3 days and 5% for strategies, because each site chose measures. Hospitals need better data

30 days. This finding adds to recent different targets and implemented systems and analytic resources to

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

e6 WU et al

participation to secure financial

resources and staff time. Several

innovations were also developed

and tested during the collaborative

period and made available to

others. Some examples include

sickle cell action plans, seizure

actions plans, a discharge lounge,

whiteboards in patient rooms

with home schedules, and peer

mentoring programs. Although

teams cited difficulties in making

timely modifications in the EMR,

many sites shared the same EMR

platform and were able to exchange

technical assistance and screen

shots of changes made such as

automated discharge readiness

reports, conditional discharge

order sets, and standardized

discharge instructions.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows the potential

benefit of the collaborative

approach to improve quality of

inpatient discharges by using an

intervention bundle implemented

in pediatric hospital settings. The

spread of such interventions has the

potential to improve care transition

outcomes for all hospitalized

children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Expert panel members: Lori

Armstrong, MSN, RN, NEA-BC; Mary

FIGURE 3

Unplanned readmission for the same condition. A, Within 72 hours; B, within 30 days (n = 5 sites Daymont, RN, MSN, CCM, CPUR;

reporting; 7654 discharges). Pamela Kiessling, RN, MSN; Cheryl

Missildine, RN, MSN, NEA-BC; Karen

more effectively plan and monitor opportunity to learn from national Tucker, MSN, RN. Data analysis: Cary

progress of quality improvement experts, share challenges and Thurm, PhD, Childrens Hospital

work. Finally, each site used different successes, learn and adapt from Association.

patient populations and different different settings and patient

tools to collect data, making the populations, and share tools such

data heterogeneous and difficult to as checklists and call scripts. ABBREVIATIONS

compare. The collaborative approach also

CHA:Childrens Hospital

helped sites develop urgency for

Association

Participating sites reported several change at the institutional level

EMR:electronic medical record

benefits of the collaborative model and fostered friendly competition

IHI:Institute for Healthcare

that were consistent with previous and accountability. Teams were

Improvement

studies.51,52 Teams enjoyed the also able to leverage collaborative

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

PEDIATRICS Volume 138, number 2, August 2016 e7

collection, assisted with data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the nal

manuscript as submitted.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-3604

Accepted for publication Mar 14, 2016

Address correspondence to Susan Wu, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles,

CA 90027. E-mail: suwu@chla.usc.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright 2016 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no nancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funding for the collaborative was provided by the Childrens Hospital Association and participating member hospitals.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 15. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Reconcilable differences: correcting 2013;8(8):421427 Services. Readmissions Reduction

medication errors at hospital 9. Williams MV, Budnitz T, Coleman EA, Program. 2014. Available at: www.

admission and discharge. Qual Saf et al. The Society of Hospital Medicine cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-

Health Care. 2006;15(2):122126 Project BOOST Implementation Guide Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS

to Improve Care Transitions. 2014. /Readmissions-Reduction-Program.

2. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al.

Available at: www.hospitalmedicine. html. Accessed September 10, 2014

A reengineered hospital discharge

program to decrease rehospitalization: org/Web/Quality_Innovation/ 16. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM,

a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. Implementation_Toolkits/Project_ et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence

2009;150(3):178187 BOOST/Web/Quality___Innovation/ and variability across hospitals

Implementation_Toolkit/Boost/First_ [published correction appears in

3. Greenwald JL, Jack BW. Preventing

Steps/Implementation_Guide.aspx. JAMA. 2013;309(10):986]. JAMA.

the preventable: reducing

Accessed May 1, 2014 2013;309(4):372380

rehospitalizations through

coordinated, patient-centered 10. Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit. 17. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney

discharge processes. Prof Case 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability

Manag. 2009;14(3):135140, quiz & Quality (AHRQ). Available at: www. of early readmissions at a childrens

141142 ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/ hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1).

hospital/red/toolkit/index.html. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/

4. Greenwald JL, Denham CR, Jack BW. Accessed September 10, 2014 content/full/131/1/e171

The hospital discharge: a review

of a high risk care transition 11. Boutwell A, Jencks S, Nielsen GA, 18. Gay JC, Hain PD, Grantham JA,

with highlights of a reengineered Rutherford P. State Action on Avoidable Saville BR. Epidemiology of 15-day

discharge process. J Patient Saf. Rehospitalizations (STAAR) Initiative: readmissions to a childrens hospital.

2007;3(2):97106 Applying Early Evidence and Experience Pediatrics. 2011;127(6). Available at:

in Front-Line Process Improvements www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/

5. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, to Develop a State-Based Strategy. 127/6/e1505

McGinn T. Medical errors related to Cambridge, MA: Institute for

discontinuity of care from an inpatient 19. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, Chung

Healthcare Improvement; 2009 PJ. Predictors of 30-day readmission

to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern

Med. 2003;18(8):646651 12. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. and association with primary

Using quality improvement to optimise care follow-up plans. J Pediatr.

6. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, paediatric discharge efciency. BMJ 2013;163(4):10271033

et al. Adverse events among medical Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428436 20. Bigham MT, Logsdon TR, Manicone

patients after discharge from hospital.

13. Shen MW, Hershey D, Bergert L, PE, et al. Decreasing handoff-related

CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345349

Mallory L, Fisher ES, Cooperberg D. care failures in childrens hospitals.

7. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson Pediatric hospitalists collaborate Pediatrics. 2014;134(2). Available at:

JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse to improve timeliness of discharge www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/

drug events occurring following communication. Hosp Pediatr. 134/2/e572

hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;3(3):258265 21. Tham E, Calmes HM, Poppy A, et al.

2005;20(4):317323

14. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Sustaining and spreading the

8. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, Rehospitalizations among patients in reduction of adverse drug events in a

et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness the Medicare fee-for-service program. multicenter collaborative. Pediatrics.

of a multihospital effort to reduce N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):14181428 2011;128(2). Available at: www.

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

e8 WU et al

pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/128/2/ 31. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Rehospitalization for childhood

e438 Assessment Scale for Collaboratives. asthma: timing, variation, and

Available at: www.ihi.org/resources/ opportunities for intervention.

22. Bundy DG, Gaur AH, Billett AL, He B,

Pages/Tools/AssessmentScalefo J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):300305

Colantuoni EA, Miller MR; Childrens

rCollaboratives.aspx. Accessed 42. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM,

Hospital Association Hematology/

September 10, 2014 et al. Same-Hospital Readmission

Oncology CLABSI Collaborative.

Preventing CLABSIs among pediatric 32. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. Rates as a Measure of Pediatric

hematology/oncology inpatients: The run chart: a simple analytical Quality of Care. JAMA Pediatr.

national collaborative results. tool for learning from variation in 2015;169(10):905912

Pediatrics. 2014;134(6). Available at: healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 43. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 2011;20(1):4651 and impact of potentially preventable

134/6/e1678 33. Provost LP, Murray SK. The Health Care readmissions at childrens hospitals.

23. Jeffries HE, Mason W, Brewer M, Data Guide: Learning From Data for J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613619.e5

et al. Prevention of central venous Improvement. San Francisco, CA: John 44. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-

catheterassociated bloodstream Wiley & Sons; 2011 Pealoza R, et al. Measuring hospital

infections in pediatric intensive care 34. Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost quality using pediatric readmission

units: a performance improvement in transition: challenges and and revisit rates. Pediatrics.

collaborative. Infect Control Hosp opportunities for improving the quality 2013;132(3):429436

Epidemiol. 2009;30(7):645651 of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 45. Nakamura MM, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky

2004;141(7):533536 AM, et al. Measuring pediatric hospital

24. Sharek PJ, McClead RE Jr, Taketomo

C, et al. An intervention to decrease 35. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis readmission rates to drive quality

narcotic-related adverse drug events MM. Pediatric hospital discharge improvement. Acad Pediatr.

in childrens hospitals. Pediatrics. interventions to reduce subsequent 2014;14(5 suppl):S39S46

2008;122(4). Available at: www. utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp 46. Press MJ, Scanlon DP, Ryan AM, et al.

pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/4/ Med. 2014;9(4):251260 Limits of readmission rates in

e861 36. Crocker JB, Crocker JT, Greenwald measuring hospital quality suggest

JL. Telephone follow-up as a primary the need for added metrics. Health Aff

25. Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

care intervention for postdischarge (Millwood). 2013;32(6):10831091

The Breakthrough Series: IHIs

Collaborative Model for Achieving outcomes improvement: a systematic 47. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al.

Breakthrough Improvement. 2003. review. Am J Med. 2012;125(9):915921 A framework of pediatric hospital

IHI Innovation Series white paper, 37. Braun E, Baidusi A, Alroy G, Azzam discharge care informed by legislation,

Cambridge, MA ZS. Telephone follow-up improves research, and practice. JAMA Pediatr.

patients satisfaction following 2014;168(10):955962, quiz 965966

26. Kilo CM. A framework for collaborative

improvement: lessons from the hospital discharge. Eur J Intern Med. 48. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg

Institute for Healthcare Improvements 2009;20(2):221225 D, et al. Summary of STARNet:

breakthrough series. Qual Manag 38. Coller RJ, Nelson BB, Sklansky DJ, et al. seamless transitions and (re)

Health Care. 1998;6(4):113 Preventing hospitalizations in children admissions network. Pediatrics.

with medical complexity: a systematic 2015;135(1):164175

27. Kilo CM. Improving care through

review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6). 49. Mittman BS. Creating the evidence

collaboration. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1

Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ base for quality improvement

suppl E):384393

content/full/134/6/e1628 collaboratives. Ann Intern Med.

28. Billett AL, Colletti RB, Mandel KE, et al. 39. Morse RB, Hall M, Fieldston ES, 2004;140(11):897901

Exemplar pediatric collaborative et al. Hospital-level compliance with 50. vretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, et al.

improvement networks: achieving asthma care quality measures at Quality collaboratives: lessons from

results. Pediatrics. 2013;131(suppl childrens hospitals and subsequent research. Qual Saf Health Care.

4):S196S203 asthma-related outcomes. JAMA. 2002;11(4):345351

29. Lannon CM, Peterson LE. Pediatric 2011;306(13):14541460 51. Leape LL, Rogers G, Hanna D, et al.

collaborative networks for quality 40. Sobota A, Graham DA, Neufeld EJ, Developing and implementing new safe

improvement and research. Acad Heeney MM. Thirty-day readmission practices: voluntary adoption through

Pediatr. 2013;13(6 suppl):S69S74 rates following hospitalization statewide collaboratives. Qual Saf

30. Boutwell A, Hwu S. Effective for pediatric sickle cell crisis at Health Care. 2006;15(4):289295

Interventions to Reduce freestanding childrens hospitals: risk 52. Nembhard IM. Learning and improving

Rehospitalizations: A Survey of the factors and hospital variation. Pediatr in quality improvement collaboratives:

Published Evidence. Cambridge, MA: Blood Cancer. 2012;58(1):6165 which collaborative features do

Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 41. Kenyon CC, Melvin PR, Chiang VW, participants value most? Health Serv

2009 Elliott MN, Schuster MA, Berry JG. Res. 2009;44(2 pt 1):359378

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

PEDIATRICS Volume 138, number 2, August 2016 e9

A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve the Discharge Process for

Hospitalized Children

Susan Wu, Amy Tyler, Tina Logsdon, Nicholas M. Holmes, Ara Balkian, Mark

Brittan, LaVonda Hoover, Sara Martin, Melisa Paradis, Rhonda Sparr-Perkins, Teresa

Stanley, Rachel Weber and Michele Saysana

Pediatrics 2016;138;; originally published online July 27, 2016;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-3604

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services /content/138/2/e20143604.full.html

Supplementary Material Supplementary material can be found at:

/content/suppl/2016/07/20/peds.2014-3604.DCSupplemental.

html

References This article cites 44 articles, 19 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/138/2/e20143604.full.html#ref-list-1

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Administration/Practice Management

/cgi/collection/administration:practice_management_sub

Quality Improvement

/cgi/collection/quality_improvement_sub

Hospital Medicine

/cgi/collection/hospital_medicine_sub

Continuity of Care Transition & Discharge Planning

/cgi/collection/continuity_of_care_transition_-_discharge_pla

nning_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2016 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve the Discharge Process for

Hospitalized Children

Susan Wu, Amy Tyler, Tina Logsdon, Nicholas M. Holmes, Ara Balkian, Mark

Brittan, LaVonda Hoover, Sara Martin, Melisa Paradis, Rhonda Sparr-Perkins, Teresa

Stanley, Rachel Weber and Michele Saysana

Pediatrics 2016;138;; originally published online July 27, 2016;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-3604

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/138/2/e20143604.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2016 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on August 15, 2016

You might also like

- Baby-MONITOR: A Composite Indicator of NICU Quality: Pediatrics June 2014Document12 pagesBaby-MONITOR: A Composite Indicator of NICU Quality: Pediatrics June 2014antoniahmatNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Document10 pagesA Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- EDA. Pediatrics 2010Document12 pagesEDA. Pediatrics 2010Carkos MorenoNo ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument11 pagesNeonatal JaundiceFiska FianitaNo ratings yet

- 7.delirium Knowledge, Self-Confidence, and Attitude in Pediatric IntensiveDocument6 pages7.delirium Knowledge, Self-Confidence, and Attitude in Pediatric IntensivemarieNo ratings yet

- Febrile Infants 8-60 Days OldDocument38 pagesFebrile Infants 8-60 Days OldDorji InternationalNo ratings yet

- Lactante FebrilDocument38 pagesLactante Febril재범No ratings yet

- The Association of Hydrocortisone Dosage On Mortality in Infants Born Extremely PrematureDocument13 pagesThe Association of Hydrocortisone Dosage On Mortality in Infants Born Extremely PrematureIntan Karnina PutriNo ratings yet

- Denver II, Dev DelDocument11 pagesDenver II, Dev DelLilisNo ratings yet

- Fuchs S Et Al. Pediatrics. 2016 138 PDFDocument7 pagesFuchs S Et Al. Pediatrics. 2016 138 PDFEsteban RamosNo ratings yet

- Two-Step Process For ED UTI Screening in Febrile Young Children: Reducing Catheterization RatesDocument8 pagesTwo-Step Process For ED UTI Screening in Febrile Young Children: Reducing Catheterization RatesJean Pierre RojasNo ratings yet

- Thesis Manuscript 16may2017Document108 pagesThesis Manuscript 16may2017deliejoyceNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022060642Document80 pagesPeds 2022060642hb75289kyvNo ratings yet

- What's The Story? Expectations For Oral Case Presentations: PEDIATRICS June 2012Document7 pagesWhat's The Story? Expectations For Oral Case Presentations: PEDIATRICS June 2012JPNo ratings yet

- Meta AnalysisDocument16 pagesMeta AnalysisSabu Joseph100% (1)

- Journal Critique in Maternal and Child NursingDocument8 pagesJournal Critique in Maternal and Child NursingAebee AlcarazNo ratings yet

- Skin Care For Pediatric2Document7 pagesSkin Care For Pediatric2Sri Nauli Dewi LubisNo ratings yet

- Consent in Child Leukemia Parent Participation and Physician-Parent Communication During InformedDocument10 pagesConsent in Child Leukemia Parent Participation and Physician-Parent Communication During InformedPutu BudiastawaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisDocument4 pagesEffects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisMiguel TuriniNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Perioperative Management of Children With Autism - A Pilot StudyDocument10 pagesEnhanced Perioperative Management of Children With Autism - A Pilot Studydra.bravodanielaNo ratings yet

- Parental Satisfaction of Child 'S Perioperative CareDocument8 pagesParental Satisfaction of Child 'S Perioperative CareHasriana BudimanNo ratings yet

- E20190178 Full PDFDocument12 pagesE20190178 Full PDF2PlusNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Informed Milestones For Developmental Surveillance ToolsDocument29 pagesEvidence-Informed Milestones For Developmental Surveillance Toolsjaque mouraNo ratings yet

- Oke 2Document4 pagesOke 2Muthi'ah Ramadhani AgusNo ratings yet

- Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Infant DevelopmentDocument11 pagesMaternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Infant DevelopmentMarcela Dalla PortaNo ratings yet

- Peds 2012-1835Document8 pagesPeds 2012-1835Naraianne FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Managementul Febrei La Copii 8-60 ZileDocument40 pagesManagementul Febrei La Copii 8-60 ZileMadalina NastaseNo ratings yet

- Early Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Under 3 Years of AgeDocument24 pagesEarly Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Under 3 Years of AgeMauricio Hernán Soto NovoaNo ratings yet

- NursingDocument9 pagesNursingrebecca.ofvNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Review of Pediatric Early Warning System ScoresDocument10 pagesAn Integrative Review of Pediatric Early Warning System ScoresKarma SetiyawanNo ratings yet

- AAP - Guideline Adoption PneumoniaDocument15 pagesAAP - Guideline Adoption PneumoniaSonia FitrianiNo ratings yet

- Common Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideFrom EverandCommon Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideGilbert I. MartinNo ratings yet

- Exploring Concerns of Children With CancerDocument7 pagesExploring Concerns of Children With CancerVanessa SilvaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Factors Associated With Preoperative Anxiety in Children Aged 5-12 YearsDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Factors Associated With Preoperative Anxiety in Children Aged 5-12 YearsVania CasaresNo ratings yet

- I PASS MnemonicDocument6 pagesI PASS MnemonicDevina CiayadiNo ratings yet

- Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: Clinical Principles and ApplicationsFrom EverandEmery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: Clinical Principles and ApplicationsReed E. PyeritzNo ratings yet

- 2017 Update On Pediatric Medical Overuse A ReviewDocument5 pages2017 Update On Pediatric Medical Overuse A ReviewIvan BurgosNo ratings yet

- Bucknall 2016Document13 pagesBucknall 2016mnazri98No ratings yet

- qt9gq0c883Document10 pagesqt9gq0c883Ena EppirtaNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric Alliance For Cordinated Care Evaluation of A Medical Home ModelDocument12 pagesThe Pediatric Alliance For Cordinated Care Evaluation of A Medical Home ModelSuzana CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022060643Document55 pagesPeds 2022060643hb75289kyvNo ratings yet

- Satisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesSatisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleVANESA REYESNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Recommendations For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric AcneDocument26 pagesEvidence-Based Recommendations For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric AcnezuliaahmadNo ratings yet

- Intimate Partner Violence, Depression, and Child Growth and DevelopmentDocument12 pagesIntimate Partner Violence, Depression, and Child Growth and DevelopmentareviamdNo ratings yet

- Brown (2001)Document13 pagesBrown (2001)Eunice_Pinto_1725No ratings yet

- Hospitalazacao Por VSRDocument12 pagesHospitalazacao Por VSRnelcitojuniorNo ratings yet

- BarrierDocument14 pagesBarrierNabil Last FriendNo ratings yet

- The Care of Adult Patients in Pediatric Emergency DepartmentsDocument6 pagesThe Care of Adult Patients in Pediatric Emergency DepartmentsFrancisca AndrezaNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationFrom EverandRelationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationNo ratings yet

- Baker 2022Document11 pagesBaker 2022ahmad azhar marzuqiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Psychosocial Education Program For Families With Congenital Adrenal HyperplasiaDocument1 pageEvaluation of A Psychosocial Education Program For Families With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasiaevita juniarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From The NOVEL Project: CONSENSUS RecommendationsDocument9 pagesPediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From The NOVEL Project: CONSENSUS RecommendationsDoraNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0207701Document22 pagesJournal Pone 0207701Intan FitayantiNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care: Building an Evidence BaseFrom EverandBehavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care: Building an Evidence BaseNo ratings yet

- Reducing Unnecessary Imaging For Patients With Constipation in The Pediatric Emergency DepartmentDocument9 pagesReducing Unnecessary Imaging For Patients With Constipation in The Pediatric Emergency Departmentbella friscaamaliaNo ratings yet

- Caregiver OM Risk Factor KnoledgeDocument8 pagesCaregiver OM Risk Factor KnoledgeMeva'a RogerNo ratings yet

- The Use of Patient Complaints To Drive QualityDocument8 pagesThe Use of Patient Complaints To Drive QualitysanaaNo ratings yet

- The Healthy Teen Project: Tools To Enhance Adolescent Health CounselingDocument4 pagesThe Healthy Teen Project: Tools To Enhance Adolescent Health CounselingFabio HimanNo ratings yet

- Children With Kidney Diseases: Association Between Nursing Diagnoses and Their Diagnostic IndicatorsDocument7 pagesChildren With Kidney Diseases: Association Between Nursing Diagnoses and Their Diagnostic IndicatorsHartanti WardaniNo ratings yet

- Early InterventionDocument24 pagesEarly InterventionmiguelNo ratings yet

- Dental AssistantDocument3 pagesDental Assistantapi-78766098No ratings yet

- Quick Selection of Chinese Herbal Formulas Based On Clinical ConditionsDocument0 pagesQuick Selection of Chinese Herbal Formulas Based On Clinical Conditionsharbor100% (1)

- DMNCP - Imbalanced Nutrition Less Than Body RequirementsDocument1 pageDMNCP - Imbalanced Nutrition Less Than Body RequirementsMel Izhra N. MargateNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6016 Assessment 1 Adverse Event or Near-Miss AnalysisDocument6 pagesNURS FPX 6016 Assessment 1 Adverse Event or Near-Miss Analysisjoohnsmith070No ratings yet

- Nursing DiagnosisDocument3 pagesNursing DiagnosislesternNo ratings yet

- JNC8 HTNDocument2 pagesJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Dis Cert NotificationDocument2 pagesDis Cert NotificationSomnath GhoshNo ratings yet

- CVDocument2 pagesCVapi-326166436No ratings yet

- Classification of ArticulatorsDocument4 pagesClassification of ArticulatorsRishiraj Jaiswal67% (3)

- Organ DonationDocument9 pagesOrgan DonationKeeranmayeeishraNo ratings yet

- PMDT Referrals - Ver 2Document15 pagesPMDT Referrals - Ver 2Mark Johnuel DuavisNo ratings yet

- Ambulatory Surgical CareDocument265 pagesAmbulatory Surgical CareThamizhanban R100% (2)

- Medical English 170X240Document408 pagesMedical English 170X240Lucia100% (3)

- AP Psychology Forest Grove High School Mr. TusowDocument81 pagesAP Psychology Forest Grove High School Mr. TusowIsabella TNo ratings yet

- tmpB433 TMPDocument9 pagestmpB433 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- App Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery 5th EditionDocument8 pagesApp Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery 5th EditionAndri Feisal NasutionNo ratings yet

- Liston's SplintDocument4 pagesListon's SplintPriyank GuptaNo ratings yet

- Meedical History FormDocument3 pagesMeedical History FormSonja OsmanovićNo ratings yet

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)Document14 pagesAmyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)undalli100% (2)

- Drug Study of FractureDocument3 pagesDrug Study of FractureMarijune Caban ViloriaNo ratings yet

- Erb's PalsyDocument18 pagesErb's PalsyMegha PataniNo ratings yet

- Dsa 1032Document166 pagesDsa 1032Shalu PurushothamanNo ratings yet

- Biopsychosocial AssessmentDocument8 pagesBiopsychosocial AssessmentAnn OgoloNo ratings yet

- Lexapro (Escitalopram Oxalate)Document2 pagesLexapro (Escitalopram Oxalate)ENo ratings yet

- The Private Science of Louis Pasteur-Book ReviewDocument3 pagesThe Private Science of Louis Pasteur-Book ReviewDanielNo ratings yet

- Truncus ArteriosusDocument19 pagesTruncus ArteriosusHijaz Al-YamanNo ratings yet

- Ethical Care 2 Nurs 217Document9 pagesEthical Care 2 Nurs 217api-283946728No ratings yet

- FE ImbalanceDocument6 pagesFE ImbalanceDonna CortezNo ratings yet

- Medication History Interview Form Demographic DataDocument3 pagesMedication History Interview Form Demographic Datakim jongin100% (1)