Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fly Fishing Techniques

Uploaded by

Jesus M. Espinosa Echavarria0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views133 pagesTecncias de Pesca con Mosca

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTecncias de Pesca con Mosca

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views133 pagesFly Fishing Techniques

Uploaded by

Jesus M. Espinosa EchavarriaTecncias de Pesca con Mosca

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 133

Hooks

‘Space limitations prevent me from describing hooks in

any detail. (That information is readily available in

other fishing books and in catalogs.) Instead, this short

section concentrates on hooks to avoid. Before reading

any further, have a look at the next diagram, which

shows a well-manufactured hook.

No matter how careful the manufacturers are, a few

faulty hooks may find their way into your hook packet.

The defects may or may not be immediately obvious. To

help you spot them, the most common faults (and some

of the less common ones) are outlined in the following

paragraphs. If you are a beginner, make sure that any

hooks you reject really are faulty. For example: some

hook eyes are intended to be straight, some hook bends

are deliberately offset, and some hooks are meant to be

barbless.

Before you start tying with a new batch of hooks, test

three or four by clamping them in the vise and “twang-

ing” them with your thumbnail. The noise and “feel”

should tell you if you have been unlucky enough to buy

a batch that are either too brittle or too soft. If the

hooks are genuinely faulty, or if you made a mistake

‘when ordering, most manufacturers and retailers will be

pleased to replace them, or to advise on other types of

hooks that may be more suited to your kind of fly-

fishing.

Hook Eyes

Reject a hook:

If there is a gap between the end of the hook eye

and the shank that is wide enough for medium-

‘gauge tying thread to pass through.

‘e If the shank tapers excessively toward the hook

eye.

‘e If the hook is otherwise badly formed.

(The faults listed here hardly ever apply to double or

treble hooks.)

Awell manufactured hook showing where possible faults

‘mav be found

Hook Shanks

Reject a hook:

@ If the shank is not absolutely straight.

@ If (for doubles and trebles only) the wires were

uneven before soldering, or the soldering itself left

the shank with a lumpy finish.

Hook Barbs

Reject a hook:

If the barb is too short and/or inadequately

formed.

¢ If the barb is not

hook.

‘¢ If the angle of the barb is too flat in relation to the

bite.

alignment with the bite of the

Hook Gapes

Reject a hook:

e If the gape widens or narrows excessively at the

hook point.

Hook Points

Reject a hook:

If the point is badly twisted.

‘* If the point is too close to the end of the barb.

“4

Flytying Materials

I do not intend to write in detail about all the different

kinds of fur and feather that the flytyer can use, because

there are already some excellent books on the subject

(see the Bibliography at the back of this book). Instead,

I want to touch briefly on the sources of materials, then

to discuss in more detail their storage. Storage is a real

problem for so many of us.

Sources of Materials

As a professional, I buy most of my flytying materials

from wholesalers. This has two advantges: (1) the stock

is guaranteed vermin-free and can be put straight into

my storage compartments, and (2) it is cheaper! The

first advantage also applies, of course, to material from

retailers but it certainly does not apply to most of the

oddments given by well-meaning friends.

Most flytyers have to buy their materials retail, and a

large proportion comes from mail order catalogs. It may

seem obvious, but before you buy I would advise check-

ing through as many fishing magazines and catalogs as

you can. This way you can often find exactly what you

are looking for, at a better price, at the cost of just a few

minutes of extra research. Beware of Dealer X, whose

inexpensive pack of seal fur contains half the amount of

fur you find in the same-price pack from Dealer A.

When you are new to flytying and have to buy un-

familiar items (several types of hackles, for example) by

mail order, it is sensible to ask the supplier to label the

goods — it can be exasperating to receive a bundle of

feathers and not know which is which!

When you order materials from an established sup-

plier, you know just what you will receive. But, whether

you are an amateur or a professional, you have no

trol over the variety of materials that well-meaning

fellow-fishermen and friends bestow on you. Over the

years I have been given (among many-other things):

‘e superb ready-cured wood-duck skins

red fox stole

jead moles in polythene bags

¢ live bantams in a crate

a barn ow that had lost an argument with a train

innumerable gray squirrel tails

¢ a collection of fur (coat) remnants from a retired

furrier

# acollection of stuffed birds from a taxidermist

# Andalusian hackles in a dirty old paper bag

© old flytying kits

© two feather hats and a left-hand fur glove from a

rummage sale

My advice is never to turn these gifts down, as long as

you think you might possibly find a use for them. The

friend who brings you something unwelcome today may

‘well bring a real gem next time — don’t discourage him!

Storing Materials

Storage is a problem that each flytyer must solve per-

sonally. How you store your materials depends on the

space you have available, the quantities you like to keep,

the range of materials you need for the flies you tie, and

0 on. It also depends on the categories you decide on:

for example, should you keep dry-fly materials separate

from the materials for saltwater flies? The snag here is

that if you do separate your materials like that, there

will inevitably be some doubling up of threads, tinsels,

furs, and so on, The professional has this same

problem — but worse.

T have to keep stock for tying every type of fly in

every category, from the tiniest dry My to the biggest

salmon fly, in a workshop that measures only thirteen

feet by ten feet (4m x 3m). Since my storage problem is

probably much worse than yours, you may be interested

in how I solve it. Among the things my workshop has

to hold are:

ome

flytying bench and chair

a hundreds of cock and hen capes, both dyed and

natural color

4 large selection of animal tails, hair, furs and so

on

countless reels of floss, thread, and tinsel, stored in

an orderly way

whole wings, loose quills, and whole skins

+ loose hackles of all colors

‘¢ hooks of all kinds

‘ereference books and reference flies (needed for

special patterns)

How can one possibly keep all these and more in a

‘small area? There are two answers. First, you need lots

and lots of drawer space; I find an old dental cabinet

(which has many wide-area drawers), filing cabinets,

and old office furniture ideal for this. Second, most

flytying materials are (thank goodness) compressible.

Tkeep a selection of my most frequently used capes in

compartments on a shelf aboVe my tying bench. The rest

of my stock is stored in paper bags, each labeled with

the cape’s color, quality and sex, in an office desk

drawer.

Hair and Fur

Hair on the skin (such as rabbit, hare, mole, and so on)

isbest stored loose. Hair tails (such as calf, squirrel, and

‘monga ringtails), horse hair and dyed seal fur are all

stored in paper bags, labeled with type and color, and

put away in a drawer. (See also ““Outsize Materials”.)

‘Tying Thread, Floss, and Tinsels

I keep three different-sized transparent plastic boxes

(one each for thread, floss, and tinsel) out-on my flyty-

ing bench. Each box contains all the colors and types I

normally use. The remainder of my stock, including

items like lurex and fluorescent threads, which I use in-

frequently, are stowed away in a drawer. | find it useful

to keep tinsel offcuts in lids out on my tying bench.

Whole Bird Skins, Whole Wings, Loose Quills, Crests

I store all these bulky items in their own paper bags,

labeled with all necessary details.

Loose Hackles

I store loose hackles in two ways. The ones I use most

frequently (like grouse, guinea-fowl and partridge

hackles) are kept, like so many other items, in labeled

paper bags in drawers. The others (mostly cockerel

hackles, both dyed and natural) are stored in labeled

glass jars on shelves around the workshop. The jars are

vermin-proof, attractive to look at, and readily iden-

tifiable.

Outsize Materials

Items too big to store easily in drawers can be a

nuisance. The best answer is a large cupboard or closet.

Like many flytyers, I keep a selection of the larger items

that I use frequently (such as. peacock tails, ostrich

plumes, pheasant and turkey tails) in a jar on the tying

bench. Most other bulky items, like large buck tails and

bundles of turkey tail feathers, can be stored in card-

board boxes and paper bags respectively. Whole skins,

from larger animals, such as deer, can be folded care-

fully and kept in stout polythene see-through bags.

Hooks

1 keep supplies of the hooks that T use most frequently in

see-through plastic boxes in a drawer, Each box is

labeled with the size and style of the hooks it contains.

Less-regularly used hooks are stowed away still in the

manufacturers’ packaging, which usually includes oiled

paper to protect the hooks from rust. I store trout/sea-

trout hooks, salmon hooks, and treble hooks in separate

places.

Reference Books

If you have room, keep your reference books in a

bookcase or on a book shelf near you so that you can see

the titles easily. It can be annoying to have to delve

through a pile of books to find the one you want when

you are halfway through tying a fly. My favorites are

listed in the Bibliography.

Reference Flies Storage of Tied Flies

‘Most flytyers like to keep reference flies so as to be able There are many kinds of ready-made boxes and wallets

to duplicate successful patterns later on. I also have to available for storing tied flies, although itis quite easy to

keep references for custom flies I have tied to

customers” special requirements. Reference flies must be

Iabeled with all relevant details, including the name of

the fly, date, unusual materials, and whether any tinsel

tused was gold or silver colored (tinsel tarnishes with time

‘and it becomes impossible to distinguish). I keep my

reference flies in labeled cellophane envelopes in an

index-file, but with trout and sea-trout patterns separate

from salmon flies.

Vermin Proofing

Most flytyers buy capes, loose feathers and other

‘materials from shops and mail order firms. These goods

are likely to have been treated, and should be vermin

free. Before storing, however, it is always wise to check

for mites and other “life”. If all is well, you need only

mothproof the materials; just add a small pinch of nap-

thalene flakes to the storage bag before putting the

materials away.

If there is “life”, wash the materials thoroughly in

warm, soapy water, rinse, and dry off most of the

moisture in a very low oven at 200'F (100°C). Then

leave the slightly damp capes to continue drying natur-

ally in a warm airy place. Store as previously explained.

To treat fresh capes and skins, remove all the fat and

loose tissue, Wash the capes or skins thoroughly in

warm soapy water. Rinse well, and then press between

sheets of newspaper to remove excess moisture. Pin the

cape or skin out onto a board (fur or feather side down)

and cover the skin with Pyrethrum powder or a 50/50

mixture of saltpeter (potassium nitrate) and alum

(double sulfate of aluminium and potassium). Be sure

to store these chemicals separately.

Now leave the skins for a few days to dry slowly, in a

warm, airy place; the covering mixture will absorb all,

the natural moisture, When dry, remove the pins, shake

off the surplus chemical, and store the materials.

Periodically recheck all materials for “life” and, if

necessary, re-treat immediately.

Storage Life

Al tying threads and materials, if treated correctly,

stored in dry conditions, and never left out in the sun,

should last for several years. If you would like to know

more about obtaining and treating materials, Eric

Leiser’s excellent Fly-Tying Materials deals with all

aspects of collecting, curing, storing, and photo-dyeing

materials. T would recommend that every flytyer read

this book.

design your own. Dry flies, wet flies, or a combination

all need different types of storage; the following list is a

selection of suitable methods.

Wet Flies:

‘e leather wallet with sheepskin lining and press-stud

fastening

+ plastic wallet with foam lining and zip fastener

‘® wooden box with foam lining

aluminum box with clips or magnetic strips to hold

flies

Dry Flies:

« plastic see-through box (several sizes available) with

compartments :

» aluminium box with compartments, each with a

spring-loaded lid

Dry and Wet Flies:

‘¢ aluminum box with clips in lid for wet flies and with

compartments with spring-loaded lids for dry flies

Poppers and Dapping Flies:

‘ plastic box with compartments and rotatable see-

through plastic lid

The Flytying Area

When choosing which room (or part of a room) to use

for flytying, remember that some surplus material will

inevitably find its way to the floor. If the room is

carpeted, a vacuum cleaner will remove most flytying

debris except hooks. A carpet “holds” most fallen

material whereas, with an uncarpeted floor, the draught

made by the rest of the family walking past scatters the

material in no time at all.

Tying Bench

Your tying bench need not actually be a bench. A table

or an old office desk will do just as well, as long as the

top is at a comfortable working height. The surface

should be big enough to lay out all the tools and

materials you need, but not so big that items on the

bench are outside comfortable reach. My own bench

has a working surface 60 in. x 30in. (1.5m x0.75m); the

top is 30in. (762mm) from the floor. It is rather small,

but so is my workshop.

Be sure that the bench does not wobble, as this may

cause small bottles of lacquer to spill and may hamper

tying. Remember, too, that the better the surface of the

bench (this particularly applies if you commander the

dining table) the more likely you will spill lacquer all

over it! If the surface needs protecting, cover it with

plasticized cloth, or something similar. Note, however,

that lacquer thinners will dissolve some types of plastic.

The top of my bench is not worth elaborate protection,

so I simply tape a medium-sized sheet of white blotting

paper to it, a practice that I recommend. The blotting

paper acts as a background against which I can see the

outline of the fly in every detail as it is being tied. The

paper's absorbing power is handy for soaking up spills,

and for wiping surplus lacquer and glue off my dubbing

needle. Blotting paper is also cheap and renewable. If

you protect a valued table with plastic cloth, T would

Still recommend laying a sheet of blotting-paper on top.

‘One last point about choosing a tying bench: be sure

that the vise clamp will fit over the thickness of the

bench top; some clamps are particularly narrow.

Chairs and Tying Position

Most people do not give much thought to this aspect of

flytying, but it is very important. I remember talking

about tying positions once with a flytyer who amazed

‘me by saying he attached his vise to the arm of the chair

he was sitting in. This meant that he had to twist sharply

round to face the vise; he did admit he suffered a bit

from backache! I would not recommend sitting like that

even if you were tying flies on only one evening a week.

Your comfort is all-important. It will enable you to put

all your concentration into tying, instead of wondering

how much longer you can put up with your aching arms

and back. Most people find that sitting in a relaxed but

upright posture, with the bench at a comfortable work-

ing height is best when tying for longish periods.

As for chairs, I have found that the best type is a

swivelling office chair with low arm rests, an adjustable

back rest, and adjustable seat height. Arm rests are

useful because, by allowing you to rest your elbows on

something firm, they help to keep your hands steady for

operations away from the vise,

shting

‘Tying Mes takes a good deal of concentrated effort, and

easily tires the mind, hands, and eyes. Even during the

daytime, it is essential to work in good light ~ whether

you are tying flies for half-an-hour or a whole day. A

bright, pteferably fluorescent, light overhead is ideal.

Should this be insufficient, you may need an additional,

spotlight. (This should never be a fluorescent light: it

will harm your eyesight.) Remember that too much

light can be just as tiring as not enough light. Aim for a

bright but comfortable level of lighting.

Preparation for Tying

Once you have organized your tying area, you need to

give some thought to laying out your tools and materials

ready for tying. Alll flytyers develop their own way of

working, which is usually reflected in the state of their

tying benches — ranging from the orderly to the

chaotic. The orderly way is much the best.

The position of the vise should be about half-way

along the near side of the bench. If you are right-

handed, the vise jaws should point right; if you are left-

handed, they should point left. Adjust the vise so that

the jaws (and thus the hook) are at a comfortable work-

ing height.

Lay out the tools, tying thread, hooks, wax, lacquer,

and materials you will need on the bench top, How you

arrange these items is up to you, but they should be

within easy reach and separate from one another. Being

right-handed, I usually keep tools and other equipment

on the right of the vise, materials on the left. If you can

develop the habit of always returning tools and equip-

ment to the same positions after you use them, your fly-

tying becomes much more efficient. With practice, you

will then be able to pick up whatever tool you want to

use next without having to fumble around or search the

bench for it, thus saving valuable time.

When preparing to tie a particular pattern, first take

out the materials and any other equipment you will

need, then take out the hook and place it in the vise.

Never do it the other way round, because a hook in the

vise can catch in your clothes as you reach for materials.

If the hook is not broken, it will be severely strained and

will have to be discarded.

‘After a tying session, you will probably leave some or

all of your equipment out on the bench — but don’t

leave anything else. Clear up the debris from the session,

so that the working surface is clean and ready for the

next one. You only need to neglect this for a few

sessions and your tying bench will be hidden under

heaps of off-cuts, rejected hackles, and other debris.

2

My Tying Style

Although the greater part of my work is tying custom

flies, I have to tie a lot of standard patterns too. The

following sequence of black and white photographs

shows how I tie a typical fly (in this case a March

Brown). This photographic sequence actually serves

three purposes. It gives an idea of the tying style I use, it

acts as a sort of visual contents list for the color section

(telling you where to find detailed instructions for each

tying stage shown), and it is almost the only place in the

book where you will see a complete fly tied from begin-

ning to end!

The March Brown (Wet Fly)

Winding the tying thread down the hook shank. (See “The

Beginning of a Fly" in Chapter 2.)

The tail — formed from a slip of hen-pheasant

feather ~ tied on with two turns of tying thread. (See,

curiously enough, “Wood-duck Tails” in Chapter 3.)

= @ double length of tying thread — about to

be tied in. (See Chapter 4.)

Forming the fly's body with dubbed tying thread; the dubb-

ing consists of fibers of hare’s-ear fur, spun onto the tying

thread, (See “Dubbing” in Chapter 4.)

Winding on the ribbing. (See Chapter 4.)

‘Trimming the tip of @ partridge hackle, before tyi

(See “Soft-hackled Flies” in Chapter 5.)

‘The wings - formed, like the tail, from slips of pheasant

feather — tied on. (See “Matched Wet Wings", Chapter 6.)

‘The trimmed partridge hackle secured by tying thread. The

downy part of the hackle is about to be trimmed off.

4

The completed March Brown (though the head

The hackle has been wound on, and the surplus is about to Jacquering), finished off with a wrap knot. (See "The Wrep

be trimmed off. Knot” in Chapter 2.)

2 Basic Techniques

Itis easy to underestimate the importance of basic flytying techniques, especially if, as with the preparation of the

hook shank, they are “hidden” in the finished fly. In fact, no part of the dressing is really hidden because poor

preparation will invariably mar the appearance of the finished fly. You cannot hope to produce well-made flies

without mastering the humble, but necessary, basics.

The techniques illustrated on the following pages are:

# how to put the hook in the vise (and how not to . . .)

# how to wax the tying thread

‘* how to start tying the thread onto the hook shank

how to finish a fly with a wrap knot

‘¢ how to judge the proportions of the parts of a fly.

For the sake of your fingers, please pay particular attention to the instructions on the right way to place a hook in

the vise. Flytying materials are colorful enough without accidentally dyeing them with your own blood. Breaking

the thread on an exposed hook-point, just as you have finished laboriously winding it down the length of the shank,

is another hazard to be avoided.

Itis important, too, 10 use well-waxed tying thread (see opposite}. It is not impossible to tie flies with unwaxed

thread, just more difficult. The wax helps the tying thread to stick to the hook and makes it easier to wind on close

turns of thread, to tie on wings, and so on, Waxing also waterproofs the thread, which improves the durability of

the fly

“The Beginning of a Fly", “The Wrap Knot”, and “The Proportions of a Fly” have their own text introductions

on the following pages. There is, however, one topic not described under “The Wrap Knot” that I should like to

‘mention here. Some flytyers prefer not only to finish the fly off with a knot, but also to use knots (usually half-

hitches) to secure all the stages of a dressing as they are tied. I do not do this, nor is it shown in this book, because

my technique of using a length of well-waxed thread, which is locked in the rubber button at every stage, makes any

further securing unnecessary. This is only my personal preference, and if you find that intermediate knots help you

to tie a better fly, then by all means use them

Placing a Hook in the Vise

=

Ca

The Wrong Way ‘The Right Way

¢ Point of hook is protruding * point of hook does not show

¢ shank is not level shank is level

‘whole gape is held, and being stressed, in vise jaws (this is © gape is clearly visible.

especially harmful to offset hooks).

Notes 2. Never put the whole gape of a hook in the vise jaws.

1. Ifthe hook point protrudes beyond the vise jaws, it can" This damages the temper of the hook, which may then

break the tying thread (or your skin) as you are tying. To break during tying or (worse) fishing.

‘make sure this cannot happen, run your thumbnail light- 3. With your thumbnail, “twang” the eye of the hook to

ly around the front of the jaws before you start tying. /f "check that the hook is held securely. Some fivtyers can

you can feel the point, reposition the hook. detect faulty hooks by listening to the tone.

2»

Waxing the Tying Thread

'¢ Holding one end of the thread in your right hand, and

the wax in your left hand, place the longer end of thread

(on top of the way

'* With the thumb of your left hand, press the thread light-

ly into the wax, as shown. Note that the two hands are

close together.

‘¢ Draw your right hand swiftly away from your left hand

until the length of thread is waxed. (Drawing the thread

through quickly melts the wax, which coats the thread

‘more evenly and reduces adhesion and the likelihood of

thread breakages.)

Repeat at least once more.

‘© ot applicable to bobbin-holder users) Turn the thread

round so that the unwaxed end may now be waxed in the

same way.

Tips

Ifthe thread keeps breaking, you may not be drawing it

through quickly or smoothly enough. If you are using tying

sik, check that it has not rotted. Otherwise, use a hes

{gauge of tying thread.

The Beginning of a Fly

To start a fly, I take a length of well-waxed tying thread

and begin winding it from directly behind (almost

touching) the eye of the hook. I then continue winding.

the thread down the shank as far as the pattern

requires. The reason for preparing a hook shank in this,

way is to give a “foundation” of thread onto which I

can easily tie the tail, body, hackle, and wings.

Some flytyers start winding on the thread foundation

well down the hook. This is fine for tying on the tail and.

body but means that the wings and hackle have to be

tied onto a bare hook shank. When they are tied on in

this way, I find that the hackles tend to pull out and the

wings tend to slip round the shank. I think it is much

easier to tie them onto a foundation of thread that starts,

by the eye of the hook.

For flies that will have tinsel or floss bodies, wind on

the foundation thread in very close, even turns; each

turn touching the last one. This helps to create a smooth

tinsel or floss body. For most other flies the turns need

not be so close, but should be evenly spaced. (If you

take pride in all aspects of your flytying, however, it

does no harm to wind on in close turns whatever the

pattern.)

(On the rare occasions when you have to start the fly at

the tail end of the hook (when tying a fly completely in

reverse, for example, with the tail tied on at the hook

eye), begin in the same way as shown in the

photographs, but start winding on the foundation

thread not at the eye but at a point about four turns in

front of the tail position. Then wind on three or four

very close turns toward the tail, cutting the surplus

thread as soon as the short end is well trapped. This

makes the length of foundation thread on the shank

very short and so you must be especially sure that any

material you tie in is well prepared and securely

attached.

a

‘¢ Hold the ond of the waxed thread at right angles to, and

‘on top of, the eye end of the hook shank, as shown, Hold

the “short” end of the thread in your left hand.

‘¢ Note how close your hands should be to the hook

shank.

‘¢ Take the longer end of thread down on the far side of

the hook, around underneath the shank, and back up the

rear side as shown. Note how the longer end of thread

traps the short end (held by your left hand) against the

hook shank.

‘© With the right hand, wind on three more close turns of

thread toward the tail end of the hook, thus securing the

short end of the thread. (S)

‘© Cut off the short end as close as possible to the turns of

thread securing it, as shown.

© Continue winding on with close turns to the point where

‘the tail will be tied in. Your next step will depend on the

pattern you are tying.

Note: The turns wound on in steps 3 and 4 need only be

close if the fly’s body is to be of tinsel or floss.

22. (S) = now secure tread in tuber burton oF leave bobbin hanging

The Wrap Knot

‘The wrap knot (also called the “whip finish”) is the best knot yet devised for finishing off a fly quickly, easily, and

securely. The only other method is to use a series of half-hitches (see steps 2 to 6, and 13, in the following sequence

of photographs), but these have a tendency to come undone, however well the thread has been waxed.

Tuse the wrap knot because most of the fishermen I supply use the double turl knot (or similar) to attach their

flies to the leader. This knot, though excellent for the fisherman, puts a tremendous strain on the knot used to

finish the fly, particularly ifthe fisherman changes his flies frequently. The wrap knot can stand up to this hard use,

especially if you strengthen it with a coat of clear lacquer

Tin the following photographs I used string instead of tying thread to show more clearly what happens when the

threads” cross. To be able to finish off a fly with a well-tied wrap knot is a satisfying part of the flytyer’s art, and

itis well worth practicing until you can finish off a fly perfectly every time. When you start to practice the wrap

knot, you may find it easier to use string (or wool) and then to progress to tying thread once you have mastered the

movements.

Finally, if you plan to use a whip finish (wrap knot) tool, please follow the manufacturer's instructions, The

result will be the same as for the method shown in this book

¢ The photograph shows the “tying thread” (string)

wound onto the hook shank ready for practice.

"Note: The last turn is shown further down the shank than

it should be, because of the diameter of the “thread”. The

‘wrap knot is normally tied just behind the eye of the hook.

‘¢ With the fingers of the right hand, form a “near triangle"

of thread, close to the hook, as shown. Note that the left

hand holds the thread in front (on your side) of the hook.

¢ Do not make the triangle too small.

« Bring the thread in the left hand down, so that it forms

a complete triangle.

Keeping the loft hand stil, twist your right hand

clockwise. Note how short the length of thread between,

hook and triangle should be.

‘© Ease the tension on the thread a litle.

# Move both hands away from you, enlarging the triangle

at the same time by opening up the right-hand fingers, un-

til the short length of thread between hook and triangle is

taken up.

© The “join” in the triangle should now be tight against

the hook shank

‘© Move your right hand so that the triangle is behind the

hook shank. (Note the positions of the right-hand fingers i

the triangle.) The bottom part of the triangle must always.

bbe under, and the top part over, the hook shank

© Koop the left hand stil

Keeping tension on the triangle, move the middle finger

of your right hand so that it is under the index finger as

shown.

© The triangle now becomes an oval loop.

‘© Move your middle finger upward unti itis alongside the

index finger.

Flatten your right hand so that the fingers face

downward.

‘© This action should give the loop a twist, as shown.

‘© Leaving the middle finger at the top of the loop, use

your index finger to push the twist toward the hook until it

rests against the far side of the hook shank.

‘© Note that the index finger should be slightly lower than.

the middle finger.

‘# Maintaining tension on the thread, move the loop down

and around behind the hook.

© Continue moving the loop around unti itis in the posi

tion shown. This completes one turn of the wrap knot.

© Go through steps 5 to 11 at least twice more.

‘¢ The three turns of the wrap knot are now complete.

‘¢ The loop is ready to be pulled through. Note that the

loop should be around the shank, as shown.

‘© Use the scissors or dubbing needle to maintain a light

tension on the loop as you pull the free end of the thread

through, so that the loop completely disappears. This

forms the fourth and final turn of the wrap knot. If you

‘cannot pull the free end through, something must have

‘gone wrong and, alas, you will have to start again from the

beginning!

‘© Cut off the loose end of thread as close as possible to

the knot. (Do not try to break it off.)

© Using the dubbing needle, coat the wrap knot with clear

lacquer.

“One-fingered” Wrap Knot

If you are very short of tying thread when you reach the wrap knot stage (because of miscalculation, perhaps, or an

earlier thread breakage), it is possible to do a one-finger version of the knot using the right-hand index finger. This

needs some practice, however, and can only be done very close to the eye of the hook. Using this dodge, you cannot

control a loop much larger than the thickness of your index finger.

Half-hitch Finish

If you find that the wrap knot defeats you, a series of half-hitches can be used instead.

To tie a half-hitch, follow steps 2 to 6, then the first part of step 13, of the wrap knot sequence. Do this at least

three times (forming three half-hitches with the loop pulled through completely each time) then finish off as

described in the last two parts of step 13

The Proportions of a Fly

When you first begin flytying, it is difficult to judge if

the flies you tie are of the correct proportions. At this,

stage it is especially useful, therefore, to seek advice

from experienced flytying friends, who are usually only

too pleased to help you with demonstrations, materials,

and (most useful of all) by providing well-tied flies that

you can compare with your own efforts. Eventually you

‘will find, as do most other flytyers, that you develop an

instinctive “feel” for proportions and it becomes a case

of “what looks right, is right.

This section gives some guidance about proportions,

and includes the following aids:

‘eA drawing of the anatomy of a natural fly, together

with a hook diagram showing positions of the various

parts of an artificial fly that are referred to in this

book.

«A series of paired photographs showing several

representative fly patterns. For each pattern one

photograph shows the correct proportions, the other

shows incorrect proportions.

« A table giving some useful rules-of-thumb about pro-

portions.

___— diy fly hackle postion

dr ty wing position

— Wot fly hackle position

Wet tly wing position

‘The hook positions for the parts of an artificial fly

Comparing Propo!

Long-tailed March Brown (Nymph) Size 8DE

(Down-eyed)

Wrong Right

Foundation thread stops too short.

Tail is too short.

Wing casing is tied on too far from the tail (which is why

the tying thread shows).

Yellow ribbing is too thick and too widely spaced.

Dubbing is lumpy and should extend the whole length of

shank.

Hackle is too short and badly prepared.

Head appears lumpy because material was tied off too near

the hook eye.

Dark Cahill (Wet Fly) Size 83DE

FS A

Wrong

Foundation thread stops too short.

Tail is too long.

Dubbing is t00 loosely applied. Also, dubbing stops short

of the hackle point (trying thread is visible)

Hackle is too long and sparse.

Wing is too short.

Head is much too big.

Greenwell’

Glory (Dry Fly) Size 8UE (Up-eyed)

Wrong

Foundation thread extends too far round bend.

Tail whisks are too thick and, because foundation thread

extends too far, the whisks are wrongly angled.

Oval gold ribbing is much too thick.

Hackle is much too long and sparse (tying thread should

not show between turns of hackle).

Wings were badly prepared, so one is lower, and thinner,

than the other.

Head is not close enough to hook eye.

Roy!

Wrong

Foundation thread stops short of bend.

Fiat gold tag should be tied in at bend.

Peacock by tail is too narrow and skimpy.

Scarlet floss is too thin.

Peacock by hackle is too skimpy and is out of proportion

with peacock at tail.

Hackle is much too short.

Streamer Hackles for the wing on the far side were badly

selected. Both pairs of hackles for the wing are unevenly

matched at the tips, and too long.

Coachman (Streamer Fly) Size 8LS (Long shank)DE

Right

~

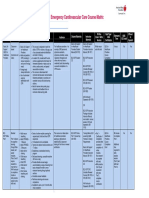

Rules-of-thumb Table for Fly Proportions

Parts of @ Fly Normal Position in Fly Normal Proportions Exceptions and Other Informatior

Foundation thread Starts behind eye, finishes For some nymphs and streamers

directly above barb thread must be taken round,

bend of hook

Tags Round bend of hook ‘Same length as finished head Choose tinsel of the right size.

‘Too-wide flat tinsel is difficult 10

handle and cuts thread when

tied in. Too-large oval tinsel

gives bulky tag

Tails Directly above barb 1 to 1% times shank Most nymph tails are about

length (eye to bend) half the shank length

Butts In front of tal One or two turns of butt

material only

‘Wing casings From tail position to head ‘Some casings are tied over

thorax only

Ribbing ‘Wound over bodies About 4 to 6 turns. Must be 1. Do not use over-wide ribbing:

wide enough to show on ‘only one or two turns will be

bodies. For dubbed bodies, possible.

use wider ribbing than normal 2, Some fine ribbing materials

only intended to protect,

the body material

Dubbing Starts at tail position, ends Aim for uniformly shaped Nymph bodies are usually

at hackle position body tapered

Hacklos

for Nymphs At hackle position ‘About % shank length (eye

to bend)

for Wet Flies ‘At hackle position Fibers should just reach the

hook point

for Dry Flies ‘At hackle position 1% to 2 times shank length _Fibers should be a little below

(eye to bend) the hook point

for Streamers ‘At hackle position Fibers should almost reach Some streamers have shorter

bend (wet-fly-proportioned) hackles

Wings

for Wet Flies Slightly forward of normal _Tied-on wing should be 1%

‘wing position 10 1% times shank length

for Dry Flies ‘At wing position Tied-on wing should be just Can be given better proportions

short of shank length by trimming the tips

for Streamers ‘At wing position Tied-on wing should be 1%

to 2 times shank length

‘Note: Shank length is measured from behind the eye to the beginning of the bend.

3 Tails

The range of materials (and colors) that can be used for the tails of fishing flies is very wide, yet many flytying

books have very little information on this subject. When | started flytying, one of my first problems was trying to

tie on a tail without clear instructions to follow; I could not understand why, as I tied a hackle fiber tail on top of

the hook, it always finished up on the far side of the shank! 1 hope that reading this chapter will help you to avoid

such difficulties.

‘Once you have learnt how to tie on a tail, you can use the same techniques for tying on any materials that are tied

‘on top of the hook: all types of wings, toppings, detached bodies, and so on. Note, though, that the materials for

these parts of the dressing must be prepared differently, and this is described in other chapters.

The photographic sequences on the following pages show how to prepare and tie on the following typical tails:

¢ Woodduck

Hackle fiber

¢ Hackle point

@ Fork

¢ Married slip

Hair

‘* Wool and synthetic yarn

There are two variations of the tail technique: one is described in detail in the wood-duck tail sequence, the other

in the hackle-point tail sequence. In the instructions for other types of tails, I therefore refer to the “wood-duck

method” or the “hackle-point method,” as appropriate.

Wood-Duck Tails

In the following sequence of photographs, you will see that I selected a slip from the left-hand side of the wood-

duck feather (see the photograph for step 2). This was so that the more distinct markings would face the camera

when I placed the tail against the hook to check the proportions. For fishing purposes it does not matter which side

the tail comes from, as long as the markings on the fibers are distinct right to the tips.

The technique shown for tying on the wood-duck tail can be used for the tail of any fly pattern that employs a

feather slip of the same shape (such as slips of pheasant, turkey, teal, swan, goose, and so on).

‘© Propare a well-marked wood-duck flank feather by pull-

ing off all the lightly marked fibers and down, as shown.

‘© Prepare the hook by winding the well-waxed tying

thread down the shank in close, even, turns to the tail

position. (S)

‘ Select a slip of wood-duck feather wide enough for the

hook size.

‘¢ Hold the slip firmly in your loft hand and pull it away

from the stalk.

1S) = now secure thread in rubber bution of lave bobbin hanging 31

‘© Transfer the slip to your right hand and hold it by the

butt.

‘# Place it on top of the hook shank to determine the

length of the tail,

Note for Steps 4 and §: In the photographs for the next

‘two steps you will see that in step 4 my index finger is ver-

tical (this is correct) but my thumb is angled away; in step

5 both index finger and thumb are angled away. | moved.

my finger and thumb back to show how the loop is

formed. In actual tying, however, both thumb and index

finger should be vertical; the loop is gripped between them,

and is effectively hidden.

‘© Hold the slip and the hook shank firmly between the tips

of the thumb and index finger of your left hand.

‘@ Hold the thread firmly, clase to the hook, and draw it

up, lightly trapping it between your left thumb and the near

side of the hook shank.

‘¢ Maintaining a firm hold on the tail and the hook, com-

plete the loop by taking the thread over the tail and down

the other side, lightly trapping it between your left index

finger and the far side of the shank

‘ Pull the thread down (not too slowly) so that the loop

completely disappears to form the first turn of the returning

‘thread, (Note that, unlike the photograph, the thread com-

ing from the shank should be at the tail position.)

‘¢ Keoping your left hand in piace, put at least one more

oop over the tail. (S)

« This photograph shows the tied-on wood-duck tail with

the thread starting to be wound back up the shank over

the foundation turns.

‘* Make sure that the locked thread is as taut as possible.

© Hold the butts gently in your left hand. (Do not pull

them, because the tail might go out of alignment.)

Trim the wood-duck butts close to the last turn of

thread. (You may prefer to re-grip the tal, rather than the

butts, when trimming, especially if your scissors are not

, sharp.)

Hackle-Fiber Tails

The hackle-fiber tail is by far the most popular kind tied, probably because hackles of every color are readily

available to all flytyers. There are no set rules for the number of fibers to a tail, but four to six fibers are enough for

most sizes of wet or dry fly.

The best hackle fibers come from the center of the hackle. For dry flies, the fibers must be stiff and springy to

keep the fly afloat. Turn a cock cape over (skin side up) and choose a hackle from the center of the extreme edge,

where you should find that the hackles are short but very stiff. For wet flies, the hackle fibers can come from almost

‘any part of the cape.

* Pull out a large hackle, by its base, from a cock cape.

@ Holding the hackle tip in your right hand, gently pull

down the fibers, several times, so they are at right angles

to the stalk. (This automatically makes the tips even.)

‘© Pull out all the down and very soft fibers in the lower

half of the hackle.

y”

f

@ Select four to six fibers from the base of the remainder

of the hackle (either left or right side). Pinch the tips of the

fibers between your thumb and index finger, then pull them

away from the hackle stalk. (If you did not prepare the

stalk properly, now remove any unwanted fibers you have

inadvertently pulled off with the selected ones!)

© Check the length of the tail fibers (held in your right

hand) against the hook, and tie them on using the “wood-

duck method.”

‘Note: So that they would show up effectively, more than

the usual maximum of six fibers were used in the

photographs.

Hackle-Point Tails

Hackle feathers that are too large to be tied in as hackles can be used to make hackle-point tails. These tails are easy

to prepare, durable and, of course, help to keep the fly afloat. They are very useful when a barred effect is required

(as provided by just the tip of a grizzly or Plymouth Rock hackle).

© Prepare the hook shank by winding on turns of founda-

tion thread to the tail position. (S)

Pull out a hackle from about one-third of the way up the

cock cape.

Place the hackle point against the hook to check the

final proportions, and select the fibers at the point of the

hackle which will form the tail.

Hold the selected fibers between your left-hand index

inger and thumb, then gently pull the remaining fibers on

sach side downward, so that they are at right angles to the

hhacklo stalk.

‘© Use straight scissors to cut the pulled-down fibers at the

angle shown. The V-shaped cutouts should meet at the

base of the hackle tip; this point is the “waist” of the

prepared hackle.

‘© Lay the prepared hackle along the near side of the

shank, with the waist af the tail position (very important)

and the outer, shiny side of the hackle facing you.

Holding the hackle point and the hook bend between

your left-hand thumb and index finger, make the first turn

of thread over the waist. While gently tightening this first

turn, ease the waist over with the thread until the hackle

point lies horizontally on top of the hook. (The hackle

tends naturally to move to the top of the shank as you

tighten the turn, but you may need more than one attempt

to get it right.)

‘© Make two more securing turns. (S) Then cut off the

surplus hackle stalk.

Fork Tails

Itis surprising that this style of tail is not more widely used. Fork tails are easy to prepare and can be used to imitate

realistically the tails of natural flies. If, for example, the tail of the fly to be imitated has only three setae, prepare a

fork tail with one fiber on one side, two fibers on the other. After tying on the tail horizontally, separate the two

fibers by winding as many turns of thread as required between them, taking each turn undet the hook.

The only disadvantage of fork tails is that the oval-shaped hackle stalk does not sit easily on the hook shank when

the hackle is placed there horizontally. This makes it especially important to select the right part of the hackle.

‘Choose a /arge hackle, and cut the fork from the top of the feather where the hackle stalk is thinnest.

* Prepare the hook shank by winding on turns of founda-

tion thread to the tail position. (S)

‘© Pull out a very large hackle, by its base, from a cock

cape.

‘* Holding the top of the hackle in your right hand, use

‘your left thumb and index finger to pull down, evenly, a

few of the fibers below. Then cut off the surplus (that is,

the hackle tip) as shown.

# Stroke the remaining fibers back to their normal posi-

tion.

# Using straight scissors, cut the hackle on both sides to

form a waist (as for the hackle-point tail) directly below the

‘two top fibers on each side.

Lay the prepared fork tail along the nearside of the

shank, with its waist at the tail position, as shown.

Tie ‘on the fork tail using the "hackle-point method.”

35

Married Slip Tails

This kind of tail (as used in the Parmachene Belle) is formed by joining (marrying) two differently colored slips of

‘swan or goose secondary wing feather. The marrying technique depends on minute hooklike projections (barbules)

‘on both sides of each feather fiber. They normally hold together adjacent fibers in the same feather, but (luckily for

the flytyer) are just as willing to grip a similar fiber from another feather

‘Note: The two slips selected should both be from the outer edges of the left or right feathers; you cannot marry

slips from left and right together. It is possible to use slips from the inner edges of feathers (if the concave curve is

not (00 pronounced) but the fibers are much softer and more difficult to marry together.

‘* Propare the hook shank by winding on turns of founda

tion thread to the tail position. (S)

@ Select and cut off a slip from the outer (usually the

shorter and stiffer) edge of a swan or goose secondary

feather.

@ Select and cut otf a slip of similar length from the same

area of the outer edge of a differently colored feather (the

second feather must be from the same side — left or

right — as the first one).

¢ Place the lower slip on your left index finger and the

upper slip alongside it so that the top fiber of the lower slip

just butts up to the bottom fiber of the upper slip. Make

sure that both slips have their dull sides uppermost or that

both have their shiny sides uppermost.

© Holding the slips between left-hand index finger and

thumb, use your right hand to marry the butts by gently

Pushing the edge of one slip against the edge of the-other.

‘* Now hold the married butts in your right hand and

gently draw the slips between the tips of your left-hand in-

dex finger and thumb, to marry the rest.

If necessary, repeat the marrying action until the two

slips are neatly joined along their whole lengths.

‘Place the married slips against the hook, to check the

proportions. If the two slips are of different depths (shorter

dimension), use your dubbing needle to remove surplus

fibers from the deeper one.

Tie on using the “wood-duck method.” (S)

Trim off the surplus according to the type of body to be

tied

36 i rubber button or eave bobbin henging

Hair Tails

All hair tails are prepared in the same way. For fly patterns with short hair tails that have to be made from naturally

Jong hair like buck tail, first cut the hair full length from the skin, then give it @ second trim to make it more

manageable. This avoids having the cropped fibers on the buck tail skin mixed up with the uncut hair.

Ido not recommend using the rejected, cropped hair for other flies, even if this does seem wasteful; it usually gives

them an amateurish, “butchered” look.

the hook shank by winding on turns of founda-

n thread to the tall postion. (S)

‘© Using straight scissors, cut a full-length bunch of hair

from the skin or tail, making the bunch a litle “fatter” than

you will need for the finished hair tail

‘© Holding the top of the bunch in one hand, run your dub-

bing needle through the lower section, several times, to

draw out the waste hairs. Then pull out any remaining

loose fibers by hand.

‘® Matching the tips: holding the bunch by its center in one

hand, use the other hand to pull out the few longest fibers.

‘© Keeping hold of the longest fibers, now pull out the next

longest fibers, holding them so that their tips are aligned

with those of the first few fibers you selected.

‘© Repeat until you are holding a tail of the right propor-

tions, made up of the fibers you have selected. Realign the

ends if necessary.

‘© Place the tal against the hook to check the length, but

do not tia it on.

‘© Hold the tail in its final position (as though to tie it on)

but be sure to gr just behind the point where it will be

tied on. Then lift it away from the shank.

@ With your dubbing needle, work glue into both sides of

the tal a, and justin front of, the tying-on point. S

Photograph

© Place the bunch at the tail position again, and tie it on

with four or five turns. (S)

‘© Trim off the glued surplus in stages along the shank,

tapering toward the eye end.

Wool and Synthetic Yarn Tails

‘The number of lengths of yarn to be tied on depends on the size of the hook and the tail thickness desired.

‘Sometimes even one length of yarn is too thick; in this case untwist the yarn and, if necessary, split it further with

your dubbing needle. For the hook shown in the photographs, four lengths of wool gave the right proportions, but

if you need to tie on six or more lengths, you must use a slightly different method. Tie them on two at a time with

very tight turns. When all the lengths are tied on, take the thread around underneath the tail (and surplus) to tighten

the tying-on turns, as if you were sewing on a button. Then take thread over tail again. (S)

For a floss or tinsel body, cut all the lengths at the hackle position, tie in the tinsel or floss, and take very close

turns of thread to the hackle position, making sure the surplus wool is tied down on top of the shank. For other

bodies, reduce the bulk of surplus wool by staggering the cut lengths down the shank.

‘¢ Prepare the hook shank by winding on turns of founda-

tion thread to the tail position. (S)

‘© Cut off the lengths) of wool required for the pattern and

hook size.

‘© Tie on the wool at the tail position, using the “wood-

duck method” (S)

© Cut the tail to the required length, fluffing it out with

your dubbing needle if desired.

© For tinsel or floss bodies: trim off the lengths of wool

leva! at the hackle position.

© For other bodies: cut the lengths of wool so that they

are staggered down the shank, as shown

‘¢ Tie down the surplus wool on top of the shank.

Some Other Tail Styles

Golden Pheasant Tippet (as used in “Pink Lady”): Pull

‘out one tippet from the tippet collar, then prepare the

tippet by pulling off all waste and lightly marked fibers.

Select between four and six well-marked fibers from

either side (holding deep orange surface of tippet upper-

most) then, gripping the tops of the selected tippet fibers

to keep them even, pull them off. Hold up the tippet

fibers to check the proportions, then tie on horizontally

using the “hackle-point method,” keeping the deep

orange side uppermost.

Golden Pheasant Crest (as used in “Campbell's

Fancy”): The litle yellow crest feathers from the golden

pheasant are among the most attractive materials

available to the flytyer. Choose a feather of the correct

size and with the best curve for the size of hook. (Badly

curved feathers should be soaked in water and reshaped

byhand on a flat surface, then allowed to dry naturally.)

Use scissors to trim the excess buff-colored downy part

of the butt (which is the strongest part of the crest) at the

same angle as shown in step 2 for the “Hackle-point

Tail.” Tie on at the waist of the prepared butt, with

crest curving upward, and cut off surplus.

Matched Tails (as used in ““Muddler Minnow”): Prepare

‘matched tails in the same way as described for ‘“Matched

Wet Wings” in Chapter 6. Tie on using the “‘wood-duck

method.”

‘Teal Tails (as used in “Rube Wood”): Teal feathers are

notoriously prone to splay out toward the tips as they

are being tied on, effectively hiding the markings on the

fibers. The only answer is to buy the very best quality

large flank feathers, and make sure that the fibers hold

together right up to the tips. Tie on using the “wood-

duck method.”

Peacock Tails (as used in “Silver Prince”): To make

thick and bushy peacock tails, choose the herls directly

below the eye of the tail feather. (The herls lower down

the feather have a thinner flue.) Cut the herls a little

longer than the eventual length of the finished tail. Mak-

ing sure that the tips are even, and the flue upper-

most, hold up the herls, adjust for final length, tie on

using the “wood-duck method”, and cut off the

surplus.

For a clipped peacock tail, proceed as above but clip

the finished tail with straight scissors. The surplus herls

cut off may be used for more tails.

Mixed Hackle Fiber and Duck Tails (as used in

“McGinty”): It does not matter which material you tie

on first, but I usually start by tying on a slip of well-

marked duck flank feather (using the “wood-duck

method”), followed by a small bunch of hackle fibers

tied directly on top. Use fibers the same length as the

slip of duck, and tie them on using the method shown

for “Hackle-Fiber Tails”. The hackle fibers must not be

t00 thick, or they will hide the duck feather.

”

4 Bodies

1 find that tying bodies is the most interesting aspect of flytying, though it is also the most time-consuming. The

body is usually the most important part of any dressing, and a wide range of materials go to make the bodies of

standard fly patterns. The imaginative tyer, who wants to devise his own patterns, has an even wider range of

potential body materials with which to experiment.

At the end of this chapter there is a fine example of innovative fly body design: Poul Jorgensen’s Stonefly

‘Nymph, included to show just how far it is possible to go in the search for realism. (Along with several other noted.

U.S. tyers, Poul is constantly improving and refining his stonefly imitations; the techniques shown here are based

on a 1976 version.) The rest of the chapter describes the materials and special techniques needed for all the most

popular styles of fly bodies. The chapter starts with the most basic body techniques, such as dubbing, the use of

tinsel, wool and chenille, floss bodies, and how to tie an underbody. It then goes on to describe the use of many

other body materials: some widely used (like pheasant tail and deer hair), some coming into favor (like latex), and

others that are used less often but are still nice to know about (such as how to make a fly body from a copper scour-

ing pad!). I cannot claim that the range of materials and techniques described is comprehensive, but this chapter

should tell you everything you need to know to tie most fly bodies.

Thave not treated the making of thoraxes as a separate subject because (for example) if the body is made of peacock

herls, one only has to wind on more herls to form a thorax. Some other materials used for building up thoraxes are

wool, raffia, floss, and polythene; for these materials, the turns must be tightened as they are wound on (see the

underbody technique, later in the chapter). Thoraxes are sometimes made from a different material from that of the

body, and have to be tied in (or dubbed) after the body is completed.

Lastly, there is one specialized subject that I reluctantly had to omit from this chapter: how to make the straw

bodies and detached horsehair bodies used in some of the old nineteenth-century trout fly patterns. They are

fascinating to make and offer a real challenge to anyone who ties flies for pure fun and would like to try something

different.

Dubbed Bodies

‘Dubbing” is the spinning of fur, wool, or other fibers

(such as polyfibers) onto the tying thread. The dubbed

thread is then wound onto the hook shank to make a fly

body with a furry texture. Bodies made in this way are

used in a large number of fly patterns, and dubbing is

certainly one of the most important flytying techniques.

Even so, I have met flytyers who despaired of ever

mastering the technique, and it usually turns out that

they have been making one (or more) of three basic,

mistakes:

1, Trying to spin too much fiber at a time onto the

thread. (The first photograph shows just how little

you need.)

2. Applying liquid wax or clear lacquer to the tying

thread before dubbing it. (My advice is never to use

liquid on the tying thread before dubbing it. I do

recommend applying lacquer or glue to the prepared

shank before winding on the dubbed thread,

however, because this helps to make a more durable

fly.)

3. Failing to bees-wax the tying thread thoroughly at the

outset. (Wax the thread four or five times before

starting to tie; the fibers will then adhere to the thread

instead of falling straight into your lap!)

0

¢ Prepare the hook shank by winding even turns of foun-

dation thread to the tail position.

‘ Use your left hand to keep the (well-waxed) tying thread

taut, and to hold a supply of dubbing material

‘¢ Take a few fibers from the supply of dubbing (the fibers

in these photographs are black-dyed seal fur).

‘¢ Put the dubbing fibers between the tying thread and the

tip of the right index finger.

Place your thumb on the fibers, as shown.

‘© Move the thumb to the right and the index finger to the

left, thus “rolling” the fibers around the tying thread. This

initial rolling action is counterclockwise, viewed from

above.

‘© Next, firmly roll the fibers back (clockwise) from the

position shown, until the thumb and index finger have

retumed to the starting position, as shown in the next,

photograph.

‘@ Repeat the firm clockwise rolling action (up to three or

four times) until all fibers have been spun onto the tying

thread,

Note: Some fine dubbing materials (such as mole fur) will

rot slide easily (next step) if spun too firmly onto the

thread,

41

# Keeping the tying thread taut with your left hand, slide 5

the first section of dubbing up the thread to the hook

shank. Twist the dubbing clockwise as you slide it up the

thread.

© Apply a second section of dubbing to the tying threed,

as described in steps 1 to 4

'® Slide the second section of dubbing up the thread,

‘twisting it clockwise, until it just touches the first section.

‘© Gently twist the fibers clockwise at the point where the

two sections touch (as shown), to join the two sections in-

to a single, uniform, length of dubbing.

‘¢ Add as many more sections of dubbing as you require.

(s)

‘ Use the dubbing needle to coat the prepared hook

shank, above and below, with clear lacquer.

‘¢ Now wind the dubbed tying thread onto the hook shank.

(s)

'# If necessary, trim the dubbed body with scissors.

For 2 bulkier dubbed body, wind the undubbed thread

back in three or four wide turns to the tail position, then do

‘steps 1 to 8 again, Repeat until the body has the required

thickness. To taper the body, start and finish each winding.

(on stage two of three turns short of the previous one, at

fone or both ends. The photographs shows a tapered

dubbed body being trimmed.

Tinsels (and Wires)

Tinsel is included in the dressings of many flies to make them sparkle and glint underwater. Tinsel packaged for the

flytyer is available in flat, oval, or round forms, and is mostly used for making, or ribbing, fly bodies. These forms

of tinsel are usually supplied on reels, and most suppliers offer a choice of widths, gauges, and colors (mostly gold

or silver, but some suppliers have other colors available).

Mat tinsel: is wound onto the hook shank to produce a fly body with a shiny, “plated” look. In narrow widths it

can also be used as ribbing for dubbed or yarn bodies. An embossed form of flat tinsel is also available; this gives

bodies extra sparkle (the effect is lessened if it is wound on too tightly). Embossed tinsel is not normally used as rib-

bing.

Oval tinsel: is manufactured by spiral-winding very narrow flat tinsel around a cotton core. It is used for ribbing

many kinds of bodies, and sometimes for securing palmered hackles. For some lake and reservoir flies, the whole

body can be formed of oval tinsel.

Round tinsel: This extremely fine material is not widely available, and is used for ribbing the bodies of very small

flies.

Wires: Solid round wires are prima

ily for ribbing, and are used in a similar way to oval or round tinsel.

The following sequence of photographs shows how to wind both flat and oval tinsel on the same body. For patterns

requiring only one type of tinsel, follow only those instructions that apply to the type of tinsel you wish to use. The

technique shown for oval tinsel is equally valid for round tinsel and for wire, except that wire has no cotton core to

be dealt with.

Notes

1. If you are not sure which size of tinsel is appropriate for a particular size of hook, there is a chart relating tinsel

sizes to hook sizes in Chapter 8.

2. Never cut metallic materials with the ends of scissor blades; always cut as far into the angle between the blades as

possible.

© To prepare for a tinsel body with an even plated

‘appearance, wind very close tums of foundation thread

down the hook shank to the tail position. (S)

© For the ribbing, cut a length of oval tinsel, probably

about four to six inches (100 to 150 mm), depending on

pattern and hook size.

'¢ Prepare one end of the oval tinsel by fraying it as

shown, then trim off the unwound metallic casing. (The

length frayed should measure from the tail position to the

point where wings and/or hackle will be tied in.)

# Holding the frayed end of the oval tinsel in your left

hand, place it under the prepared shank in the angle be-

tween the shank and the secured tying thread.

‘© Tie in the oval tinsel, just behind the start of the frayed

section, with one turn of thread as shown. Angle the

frayed section toward the hook eye. (S)

‘© Cut a length of fiat tinsel, about nine to twelve inches

(230 to 300 mm) and, for tinsels wider than 1 mm, trim one

‘end to the angle shown in the sketch.

‘¢ Hold the flat tinsel in front of the secured tying thread as

shown, with the trimmed edge nearest the bend of the

hook.

Tie in the flat tinsel with two turns of thread. (S)

palate ie

‘© Spread the frayed ends of the oval tinsel evenly along,

and underneath, the shank.

‘¢ Holding the frayed ends in place under the shank with

your left thumbnail, bind in the frayed ends and flat tinsel

end by winding the tying thread back to the eye in close,

even, tums. (S)

‘© Gently pull the flat tinsel downward, giving it a half twist,

clockwise (viewed from above). This ensures a neat

appearance at the tail end.

© Using the dubbing needle, coat the prepared hook shank

with glue, both above and below. Work quickly before the

glue dries,

‘© Wind on the flat tinsel in even tus, so that the rear

edge of each turn abuts the front edge of the previous

tum. Do not overlap the tums, or leave any gaps. Any

surplus glue that oozes out will be removed in a later step.

Remember to leave enough space for the hackle and/or

wing.

‘© On reaching the hackle position, bring the flat tinsel

around in front of the secured tying thread and, keeping

the tinsel taut, tie it off by trapping it with three turns of

thread. (S)

‘¢ Trim off the surplus flat tinsel as close as possible to the

tying-off turns.

© Use a strip of chamois leather to buff up the flat tinsel

‘on the body. This action removes most of the surplus glue

(the rest can easily be removed by hand) and also gives the

body added luster.

‘® Wind on the oval tinsel to form the ribbing. All oval

tinsel has a cotton core which can make the tinsel twist

‘and deform as it is wound on. To avoid this tendency, hold

the tinsel as close as possible to the hook shank while

winding on.

© Bring the oval tinsel around in front of the secured tying

thread and, keeping it taut, tie it off by trapping it with

three tums of thread. (5)

‘© Cut off the surplus oval tinsel (but not the tying thread)

as close as possible to the tying-off turns.

Wool and Chenille

Wool and chenille can be used for the wound bodies of many fly patterns (though wool is more often used as a dub-

bing material). Different patterns and different hook sizes require different thicknesses of these materials; wool can

be split into strands as needed (see “Wool Tails” in Chapter 3) but chenille cannot, and the flytyer must select thick,

medium, or thin gauge. Both materials are available in a wide range of colors and styles, including tinselled, bi-

colored, and fluorescent. (For convenience I cut a length of each color stocked, knot the ends together, and hang

the lengths up near my bench; this saves me having to rummage around in the bottom of a drawer to find the exact

color, I need.)

‘Wound-on wool and chenille can, unless you are careful, produce the most bulky and unnatural-looking bodies.

‘You can avoid this by careful preparation and tying-in especially when dressing wool bodies in which strands of two

different colors have to be combined.

‘The following sequence of photographs shows how to tie the wound bi-color chenille body of a Western Bee (but

the same general method also applies to wound wool bodies). Steps 1 to 3 show the initial tying-in of a length of

chenille; this method is suitable for many other body materials and is referred to as the “‘chenille method” elsewhere

in the chapter. Note, however, that the preparation of other materials may be quite different,

‘¢ Prepare the hook shank with even turns of foundation

thread to the tail position. (S)

‘® Good quality chenilles are manufactured with a “pile

(like @ carpet). Hold one end of the length of chenille

between thumb and finger, and run your fingers down it.

If it feels rough, tie in the end that is at the bottom of

your length of chenille. If your fingers run downward

“with the pile” (that is, you feel no resistance). tie in the

top of the length.

Cut a sixinch (150 mm) length of black chenille. Prepare

% inch (6 mm) of one end by pulling out the chenille

fibers, leaving just the cotton strands.

© Hoiding the chenille about % inch (20 mm! from the

prepared end with your loft hand, place the strands directly

in front of the tying thread, as shown.

Bring the chenille up, so that the strands are underneath

the shank,

‘¢ Trap the strands against the far side of the shank with

the left-hand middle finger, as shown. Keeping the long

end of the chenille well to the left, tie in the strands with

two tums of thread,

« Continue winding the tying thread toward the eye, bind-

ing the strands underneath the shank (keep them there

BE with the left-hand thumbnail). Take these turns far enough

toward the eye to allow room for the next stage (see steps

8 and 6). (S)

© Take the chenille up and over the shank (away from

you) and continue winding so that each turn touches the

last one. The Western Bee has four bands of chenille (two

each of alternating black and yellow), so wind this first

band on for one quarter of the body length. No tying

thread should show between the turns,

© Maintaining a light tension on the chenille with the /eft

hand, use your right hand to unwind the extra tums of ty-

ing thread to the point where the first band of chenille is to

be tied off,

Bring the chenille in front of the tying thread (and

‘almost parallol with the shank); then take the tying thread

‘over the shank to lock the chenille as shown,

‘© Wind on at least one more turn of tying thread. (S)

© Cut off the surplus black chenille close to the securing

‘turns of thread

‘¢ Pull out excess chenille fibers from the cut end remain-

ing on the hook.

(3) = now secure tread in rubber button of ave bobbin hanging 47

‘© Now prepare, tie in, wind on, and tie off the first band

of yellow chenille in exactly the same way as just described

for the black chenille. 1S)

Cut off the surplus yellow chenille close to the securing

turns of thread.

‘© Pull out any excess chenille fibers from the cut end on

the hook,

‘¢ Add alternate bands of black and yellow chenille as

already described. Tie off the final yellow band, (S) and

closely trim off the surplus.

‘© The finished body of a Western Bee.

‘© To complete the fly, tie in a ginger cock hackle (see

“Soft Hackled Flies” in Chapter 5), wind it on, and then tie

off. (S) Add a pair of gray duck wing slips (see “Matched

Wet Wings” in Chapter 6), cut tho surplus, and finish with

a wrap knot. Lacquer the head.

Underbodies

An underbody provides a specially-shaped foundation on top of which the final body can be tied. Many fly patterns

(especially those imitating the bulkier natural insects) require underbodies, as do some of the body techniques

illustrated later in this chapter, so it is worthwhile to have this short section on how to tie them.

Underbodies are formed from wound-on floss, wool, or polypropylene yarn of a suitable color. The following

photographs show how to tie an underbody that is tapered at both ends. However, underbodies can also be made

cylindrical, cigar-shaped, or carrot-shaped, and they can be made slim or fat as the pattern requires. The shape

depends on where you finish winding each successive “row” of underbody material, and the thickness depends on

how many rows you wind on and the thickness of the underbody material

¢ Prepare the hook shank by winding even turns of foun-

dation thread to the tail position. (S)

Tie in a length of fioss, wool, or polypropylene yarn,

using the chenille method; then wind the tying thread back

to the eye. (S)

‘* Wind on the underbody material to the desired shape (as

already described). Yarn and floss must be spread, and

wool untwisted, as they are wound on. At intervals, use

‘your index finger and thumb in a rolling action to tighten

the turns.

® Tie off the underbody material. (S) The photograph

shows an underbody shape suitable for a woven fly body,

3 described later in this chapter.