90%(10)90% found this document useful (10 votes)

3K views546 pagesPower Plant Performance Monitoring

Power Plant Performance Monitoring

Uploaded by

denni judhaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

90%(10)90% found this document useful (10 votes)

3K views546 pagesPower Plant Performance Monitoring

Power Plant Performance Monitoring

Uploaded by

denni judhaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

Power Plant Performance

Monitoring

Rodney R. Gay

With

Carl A. Palmer

Ne LIBS ae nat

TECHNIZ BOOKS INTERNATIONAL

Power Plant Performance Monitoring

Rodney R.Gay

Carl A. Palmer

Michael R. Erbes

TECH BOOKS INTERNATIONAL

Publishers & Distributors

New Delhi-110019, India

© 2006 Tech Books International, New Delhi-110019, India,

First Indian Edition

All rights reserved. No Part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any

electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and

recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the

Publishers.

Published by .

‘TECH BOOKS INTERNATIONAL

Publishers & Distributors

4/12, Kalkaji Extn., Opp. Nehru Place, Kalkaji, New Delhi -110 019, India

Phone : (011) 26284791, 26284790, 26414791 Fax: 91-11-26473611, 26231799

E-mail : abitechbooks@ vsnl.net; booksales@bol.net.in Visit us at : wwww.technobooks.com,

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gay, Rodney R,

Power plant performance monitoring / by Rodney R.

Gay, Carl A. Palmer, Michael R. Erbes, - Ist ed.

pem.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

LCCN 2004096640

ISBN 81-88305-83-9

1. Electric power-plants--Efficiency. 2. Plant

performance--Monitoring. I. Palmer, Carl A.

IL Erbes, Michael R. I]. Title.

‘TK1005.G39 2006 621.3121

(QB 104-200607

ISBN : 81-88305-83-9

Dedicated to the most important people in my life:

Henry, my father who taught me to be curious

Joan, my mother responsible for my success in life

Wendy, my wife, companion and friend for 27 years and for life

Christopher, my son who is nearly perfect

Richard, my twin brother and good friend

David, my brother, tennis partner and hiking buddy

Timothy, my brother who gives me medical and political advice

William, my grandson who makes me smile

Authors

Rodney R. Gay received his PhD in mechanical engineering from Stanford

University in 1975. He served as founder and president of Enter Software,

Inc. from 1988 until the company was sold to General Electric in 1999. He

remained as president of GE Enter Software for two years, then left GE to

become a writer and engineering consultant.

Carl A. Palmer earned his PhD in mechanical engineering from the

University of Wisconsin in 1991, after which he became an employee with

Enter Software, Inc. Carl is currently an engineering manager working on

sensor development for the power industry.

Michael R. Erbes received his PhD in mechanical engineering from

Stanford University in 1987. He co-founded Enter Software, Inc. in 1988

where he served as vice president and director of engineering. Mike is now

president of Enginomix, LLC (www.enginomix.net), a consulting and

software development company focusing on integrated engineering and

economic modeling solutions for power plant design and operations.

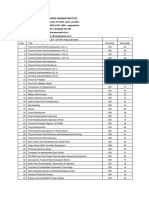

Table of Contents

Foreword 5

1. Overview of Performance Monitoring B

1.1 Concept of Performance Monitoring 13

1.1.1 “Where You Are” Vs “Where You Should Be” 13

1.1.2 Performance Calculation Procedure 7

1.1.3 Expected Performance: “Where You Should Be” 18

1.1.4 Equipment Ratings 20

1.1.5 Corrected Performance 26

1.1.6 What is My Degradation? 29

1.1.7 How Much is Degradation Costing Me? 30

1.1.8 Optimization: “Where You Could Be” 32

1.1.9 Controllable Loss Displays 33

1.2 ASME Test Codes 35

1.3. Performance Testing versus Online Monitoring 37

1.4 Curve Based Methods 38

1.4.1. Performance Curves 38

1.4.2 Expected Performance from Curves. 44

1.4.3 Additive Performance Factors 46

1.4.4 Expected Performance from Curves 47

1.4.5 Correction Factors 50

1.4.6 Percent Change Correction Factors 53

LS Model-Based Performance Analysis 54

2. Heat Balance Analysis 63

21 Local Heat Balances 64

2.2 Combined-Cycle Overall Plant Heat Balance 9

23 Combined-Cycle Balence Using Commercial Software 76

2.4 — Rankine-Cycle Overall Plant Heat Balance 9

2.5 _ Rankine-Cycle Balance Using Commercial Software 85

3. Data Validation 89

3.1 Definition of Data Validation 89

3.2 Range Checking 90

3.2.1 Static Ranges 90

3.2.2 Dynamic Ranges 90

3.2.3 Rejected Values 92

3.3 Averaging Sensor Data 93

3.4 Time Averaging 94

be Heat Balances for Data Validation 9o7

4. Accuracy of Calculated Results 105

4.1 Instrument Error 105

4.1.1 Measurement Error

4.1.2. Random Uncertainty

4.13. Systematic Uncertainty

4.2 Uncertainty of a Calculated Test Result

4.3 Monte Carlo Method

4.3.1 Definition of the Monte Carlo Method

4.3.2 Probability Distributions

4.3.3 Sampling from Probability Distributions

43.4 Running the Monte Carlo Simulation

4.3.5 Results of the Monte Carlo Simulation

Overall Power Plant Performance

5.1 Equipment Performance versus Plant Performance

5.2 Specification of Overall Power Plant Performance

5.3 Overall Plant Expected Performance Models

5.3.1 Curve-Based Method Expected Plant Perf

5.3.2. Model-Based Method Expected Plant Perf

5.3.3 Impact Method Jor Expected Plant Performance

5.4 Degradation of the Overall Power Plant

Impacts of Degradation on Overall Plant Performance

6.1 Definitions of Plant Impacts

6.2 Gas Turbine Impacts

6.3 Heat Recovery Steam Generator Impacts

6.4 Steam Turbine Impacts

65 Boiler Impacts

6.6 Feedwater Heater Impacts

6.7 Condenser Impacts

6.8 Cooling Tower Impacts

6.9 Inlet Air Filter Impacts

6.10 Exhaust Pressure Loss Impacts.

Gas Turbine Performance

7.1 Overview

7.2 Power Generation

7.3 Airflow, Firing Temperature and Pressure Ratio

7.4 Control Algorithms

7.5 Correction Curves (Baseload Performance)

7.5.1" Effect of Inlet Temperature

7.5.2 Effect of Inlet Humidity

7.5.3 Effect of Atmospheric Pressure or Altitude

7.5.4 Effect of Inlet Pressure Loss

7.5.5 Effect of Exit Pressure Loss

7.5.6 Effect of Steam or Water Injection

7.6 Part-Load Performance (Industrial Engines)

105

107

108

109

110

110

MW

113

115

115

7

117

119

122

122

124

126

128

129

129

131

135

136

137

139

140

141

142

144

147

147

147

149

153

156

159

159

160

162

163

164

166

17

78

19

7.10

7

7.12

7.13

114

715

Part-Load Correction Curves

7.7.1 Under-Firing Correction

7.7.2. Inlet Guide Vane Correction

7.7.3 Part-Load Expected Heat Rate

Aeroderivative Engine Performance

Overall Gas Turbine Heat Balance

7.9.1 Determination of Exhaust Gas Specific Heat

7.9.2. Detailed Gas Turbine Heat Balance

7.9.3. Tuning Detailed Gas Turbine Heat Balance

7.9.4 Step-by-Step Solution of the Equations

7.9.5 Simultaneous Solution of the Equations

7.9.6 Combustion Mass Balance Analysis

7.9.7 Specific Heat of a Mixture

Model-Based Gas Turbine Heat Balance

Physically-Based Models of Expected GT Performance

Gas Turbine Performance Evaluation

A theoretical degradation curve versus time is in

Experience with Measured Data from Operating GT

Performance Degradation and Engine Life

Heat Recovery Steam Generator Performance

8&1

8.2

83

8.4

85

8.6

8.7

88

8.9

8.10

8.11

8.12

Overview

8.1.1 Economizers

8.1.2 Evaporators

8.1.3 Blowdown

8.1.4 Superheaters

Duet Burner

HRSG Efficiency and Effectiveness

Expected HRSG Performance

8.4.1 Effect of Duct Burner Firing

8.4.2 Effect of Exhaust Gas Temperature

8.4.3 Effect of Exhaust Gas Flow

8.4.4 Effect of Steam Pressure

HRSG Heat Balance Analysis

Model-Based HRSG Heat Balance Analysis

Expected Section-by-Section Performance

Impact of Fouling on HRSG Performance

HRSG Performance Evaluation

Example Performance Analysis Fouled HP Evaporator

Example of Section-by-Section Expected HRSG Perf

Conclusions and Recommendations

Steam Turbine Performance

9.1

Overview

168

168

169

172

174

177

179

185

195

197

198,

201

209

210

214

216

225

226

227

231

231

232

235

245

246

248

251

257

260

263

264

265

266

273

280

284

289

294

297

299

301

301

9.2

93

94

9.5

9.6

97

98

99

Steam Turbine Configurations

9.2.1 Inlet Section

9.2.2. Condensing Section

9.2.3 Back-Pressure Steam Turbines

9.2.4 Extractions

9.2.5 Controlled (‘Automatic’) Extraction

9.2.6 Uncontrolled Extraction

9.2.7 Admission

9.28 Reheat

Seals and Leaks

Steam Turbine Thermal Performance

9.4.1 Steam Turbine Efficiency and Heat Rate

9.4.2 Pressure, Temperature and Flow Relationships

Steam Turbine Heat Balance Analysis

9.5.1 Combined-Cycle ST Heat Balance Analysis

9.5.2 Rankine Cycle ST Heat Balance Analysis

Curve-Based Expected Performance

9.6.1 Rankine Cycle ST Correction Curves

9.6.2 Combined Cycle ST Performance Curves

Model-Based Expected Steam Turbine Performance

9.7.1 Expected Performance of Overall ST

9.7.2 Section-by-Section Expected ST Performance

Building ST Expected Performance Models

Steam Turbine Degradation

Boiler Performance

10.1

10.2

10.3

10.4

10.5

10.6

10.7

10.8

10.9

Boiler Efficiency

Theoretical Air

Boiler Losses

Flue Gas Loss

10.4.1 Generalized Chemical Balance Method

10.4.2 Products of Combustion Method

10.4.3 Loss Due to Moisture

Loss Due to Ash

Loss Due to Radiation

Credits for Heat Addition to Boiler

Boiler Heat Balance Analysis

10.8.1 Furnace Heat Balance Analysis

10.8.2 Analysis of Boiler Convective Heat Exchangers

10.8.3 Desuperheater Heat Balance

10.8.4 Air Heater Heat Balance

10.8.5 Simultaneous Solution of the Equations

Model-Based Boiler Heat Balance Analysis

302

302

308

314

315

315

316

320

321

323

325

325

328

329

329

335

341

342

345

348

348

352

355

362

367

367

369

372

373

373

374

375

379

379

380

381

385

395.

396

397

399

408

2

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

10.10. Expected Boiler Performance

10.10.1 Curve-Based Method for Exp Boiler Perf

10.10.2 Model-Based Expected Boiler Performance

10.11 Boiler Degradation

10.12 Sootblowing Analysis

Air Heater Performance

11.1 Overview

11.2 Air Heater Heat-Balance Analysis

11.3 Air Heater Expected Performance

11.4 Air Heater Degradation

Feedwater Heater Performance

12.1 Overview

12.2 Feedwater Heater Heat-Balance Analysis

12.3. Expected Feedwater Heater Performance

12.4 Feedwater Heater Degradation

Deaerators, Drums and Open Heaters

Condenser Performance

14.1 Overview

14.1.1 ASME Method for Condenser Heat Transfer

14.1.2 The HEI Method for Condenser Heat Transfer

14.2 Condenser Heat Balance Analysis

14.2.1 Overall Plant Energy Balance for Cond Duty

14.2.2 Steam Turbine Expansion Line Analysis

14.2.3 Condenser Heat Balance Equations

14.2.4 Condenser Cleanliness from Measured Data

14.2.5 Validation of Condenser Heat Balance Data

14.3 Condenser Expected Performance

14.3.1 Predicting Expected Condenser Performance

14.4 Condenser Degradation

14.5 Diagnosing Condenser Performance Problems

Cooling Tower Performance

15.1 Overview

15.2 Cooling Tower Performance Curves

15.3 Cooling Tower Heat Balance Analysis

15.4 Expected Cooling Tower Performance

15.5 Cooling Tower Degradation

Inlet and Exhaust Pressure Losses

16.1 Overview

16.2 Fitting the Pressure Loss Equation to Data

16.3 Pressure Loss Degradation

Pump Performance

17.1 Overview

410

412

416

426

430

433

433

440

443,

44s

447

447

449

453

437

461

461

461

464

466

467

467

468

469

47

474

415

475

477

480

487

487

490

493

500

502

503

503

504

505

507

507

17.2

173

174

17.5

17.6

17.7

17.8

Extended Bernoulli Equation

Pump Curves

Affinity Laws

Corrected Pump Performance

Pump Flow Control

Model-Based Pump Performance

Pump Degradation

References and Links

Nomenclature

APPENDIX Definition of Terms

507

512

514

sis

518

519

521

523

527

531

Foreword

I developed an interest in performance monitoring in 1983 when I worked as

a consultant to Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E). I was asked to review

measured data from the steam cycle of a nuclear power plant. The task was,

to evaluate feedwater heater performance by comparing plant measured data

toa PEPSE™ computer model (built by someone else at PG&E) of the

steam cycle, and identify any discrepancies which might indicate a

performance problem.

I compared the measured feedwater heater TTD’s (terminal temperature

differences) to the predictions of the PEPSE™ model. The computer code

predicted integer numbers for each of the feedwater heater TTD’s. The

measured data was within 43 F of the predicted values from the computer

code for all of the feedwater heaters, but did not match any of them.

The fact that the predicted TTD’s were integers indicated to me that the

computer model was a design prediction of the plant performance, and that,

the TTD’s were inputs to the analysis. Did the predicted results mean that

some of the feedwater heaters were better than expected, and that some of

them were fouled? Or was this computer prediction just a theoretical design

model that did not necessarily represent reality at the plant. [ did not know,

so I decided to run some alternate computer calculations to see if I could

learn more.

Tlooked at the measured drain flows from each feedwater heater. I knew

that the TTD’s and the drain flows were related to each other by mass and

energy balances. The beauty of a computer code like PEPSE™ is that all

these mass and energy balances are automatically calculated. I just needed

to input plant measured data (TTD’s), and PEPSE™ would calculate heat

balance data that is consistent with my inputs.

Unfortunately, the measured drain flows bore little resemblance to the

computer calculated values for these flows. Typically the calculated flow

values were different from the measured values by 30% or more. I came to

the conclusion that the measured drain flows were of little value. A PG&E

engineer confirmed that the drain flows were known to be inaccurate.

I decided to see what effect a TTD has on the overall steam-cycle

performance. I chose a feedwater heater that appeared to be performing

poorly (TTD measured three degrees F higher than predicted) and entered

this measured TTD into the PEPSE™ input field for the chosen feedwater

heater. I ran the PEPSE™ prediction and was astonished to see that the only

predicted result than changed very much was the TTD for the feedwater

Foreword

heater that I had input to the analysis. The remained of the steam cycle was

almost unchanged. The feedwater temperature at the exit of every feedwater

heater, except for the one feedwater heater that I changed, was exactly the

same as in the original computer prediction.

This exercise taught me the difference between design analysis, where

equipment operating data (such as a TTD) is input, and an off-design

analysis (also called predictive analysis) where the equipment performance

capabilities (such as surface area and heat transfer coefficient at the design

point) are input and the operating data is predicted. In my case, the

computer analysis increased the size (heat transfer coefficient times surface

area) of the feedwater heater following the degraded feedwater heater such

that the fall-off in feedwater temperature caused by the degradation in one

feedwater heater was exactly made-up by the improved performance in the

following feedwater heater. I refer to design analysis as running the

“tuber” power plant because the heat balance code changes the size of

plant equipment to meet the specifications (temperatures, flows, power

levels and pressures) of the software user.

‘The concept of design analysis versus off-design analysis was not developed

{for application to performance monitoring, but it has turned-out to be one of

the key characteristics that makes heat balance codes useful as the

calculation engines for on-line performance monitoting systems.

Performance monitoring involves the comparison of current performance to

expected performance. Design analysis can be used to mach a computer

heat-balance analysis to the current plant operating conditions (current

performance), and the off-design analysis can be used to predict the

expected equipment performance (expected performance) given those

current operating conditions.

Later in my career, when my company developed the GateCycle™ heat

balance code, the concept of design versus off-design analysis was built

directly into code structure. We wanted it to be easy for a user to establish

the design-point performance of a power plant in one calculation, and then

switch to the off-design analysis to predict the power plant performance

over a range of postulated operating conditions.

Several vendors of commercial heat balance products have built the concept

of design versus off-design analysis into their produets. The GT PRO™ and

STEAM PRO™ products from Thermoflow, Inc. perform design analysis,

and allow the user to transfer the results of the design analysis to the

predictive (off-design) analysis that is done by the GT MASTER™ and

STEAM MASTER™ computer codes.

Foreword

The GateCycle™ user can establish the design-point performance of a

power plant in one calculation, and then switch to off-design analysis (by

clicking a check box on the user interface) to predict the power plant

performance over a range of postulated operating conditions.

PEPSE™ allows the user to perform design or off-design analysis through

the option to either input a desired equipment output parameter (such as

feedwater heater TTD), or detailed equipment characteristics (such as the

number of tubes, the tube sizes, the tube material and surface type of a heat

exchanger). The choice of inputs must be selected individually for each icon

in the PEPSE™ model.

‘The engineer that I reported to at PG&E just wanted me to compare the

predicted temperatures to the measured temperatures, and identify any

potential problems. Unfortunately there were too many discrepancies, and I

didn’t know how to resolve them. I soon realized that the running of a

design computer model of the plant and comparing to measured data was

not an adequate process to identify equipment degradation.

I describe this example to illustrate the point that it is not obvious how to

use commercial heat balance codes to monitor performance, even when you

are familiar with all of the inputs and outputs of the heat balance code. 1

spent next two decades developing and implementing procedures for using

heat balance analysis and commercial computer codes to monitor the

performance of power plants and their equipment. This book documents

what I learned.

Returning to the discussion of the performance monitoring evaluation at the

PG&E nuclear power plant, I can now say what I should have done to

evaluate the plant data back in 1983.

First, I would assume that the PEPSE™ computer model, given to me by

PG&E, was a design analysis model that matched a vendor heat balance or

guarantee prediction of the power plant performance at full load. The TTD’s

in this model probably came from a heat-balance diagram delivered to

PG&E by the plant vendor. This model would become the basis of

predictive models for the expected performance of the plant equipment.

The equipment performance characteristics from the design model, such as

the UA (heat transfer coefficient multiplied by surface area) of each heat

exchanger, and the design isentropic efficiency of each steam turbine

section, would be the inputs to the predictive (off-design) models. I would

copy and rename the design PEPSE™ model, and then manually edit the

inputs from design to off-design for each piece of plant equipment in the

Foreword

PEPSE™ model (these equipment inputs are changed for you automatically

in GateCycle™ by selecting the off-design analysis mode),

Fora feedwater heater, the input would be changed from TTD to surface

area plus the design value of heat transfer coefficient. If I did not know the

actual surface area, I would choose a correlation for heat transfer coefficient

and then iterate on the input value of surface area until the feedwater heater

TTD matches the value used in the design analysis. The only requirement is

that the product of surface area and heat transfer coefficient result in the

desired TTD. I would then run this off-design PEPSE™ model to confirm

that its prediction matches the results of the design model when the plant is

running at the design operating conditions.

I would now have two PEPSE™ models, the original design model and an

expected plant performance model that matches the design model at the

design plant operating conditions, and will correctly predict plant

performance at various plant operating conditions (such as changes in load

or environmental conditions). The original design model would not correctly

predict plant performance over a range of plant operating conditions because

the TTD’s (and other parameters) are held constant,

I will also need separate PEPSE™ expected performance models of each

feedwater heater, each steam turbine section and the condenser. These

models will be used to predict the expected performance (TTD, condenser

pressure, steam turbine power) of each piece of plant equipment. Each of

these PEPSE™ models would contain a single piece of plant equipment plus

sources representing the flows into the equipment from other locations in

the steam cycle, and sinks to receive the flows going out of the equipment.

I would use the following procedure to evaluate the performance of the

feedwater heaters.

1, Perform Plant Heat Balance Analysis

Run the design PEPSE™ model of the overall plant with plant

| measured data (such as the TTD of each feedwater heater) as the

input Values to each piece of equipment in the plant. This is called

the “heat balance analysis” of the power plant. The heat balance

analysis yields a set of current plant operating data that matches the

plant measured data, but is more complete than the measured data.

This heat balance data will include all the steam turbine extraction

flow rates and their enthalpies, and it will also include feedwater

heater drain flow rates that are consistent with the extraction flows

and the feedwater heater TTD’.

Foreword

2. Calculate Expected Equipment Performance

Predict the expected performance of each feedwater heater using a

separate PEPSE™ model for each feedwater heater. The inputs to

each feedwater heater model are the mass flow rates and enthalpies

of all three streams that flow into the feedwater heater: the extraction

steam, the feedwater and the incoming drain water from the higher

pressure heaters, The design heat transfer characteristics (UA) of

each feedwater heater are part of the input data for each feedwater

heater. The expected feedwater heater outlet temperatures (from

which TTD and DCA can be calculated) are outputs of this

calculation.

3. Evaluate Degradation

Degradation is based upon the difference between the current

performance and expected performance. The current performance of

‘a feedwater heater is the measured TTD. The expected performance

is the expected TTD, calculated for each feedwater heater. The

difference between the measured TTD and expected TTD is an

evaluation of degradation in the feedwater heater.

The expected TTD’s from the above performance monitoring procedure will

be very different from the design point TTD’s that were used as inputs in the

original PEPSE™ model. Visualize what would happen if one feedwater

heater is degraded such that its TTD is three degrees higher than the design

TTD. The plant heat balance analysis (step 1. above) will calculate a lower

extraction flow for this degraded feedwater heater. This lower extraction

flow will result in higher steam turbine pressure at the extraction location

and at all the extraction locations downstream in the steam-turbine steam.

path. These higher extraction pressures result in higher steam saturation

temperatures, which will change the TTD’s of all the feedwater heaters

receiving this higher pressure steam.

The higher TTD from the degraded feedwater heater will result in a lower

feedwater temperature at the inlet to the next (higher pressure) feedwater

heater, and this will change both the TTD and the extraction steam flow to

that higher pressure feedwater heater. The changes in extraction flows will

change the steam turbine power and the exhaust energy from the steam

turbine, which changes the condenser pressure.

These complex interrelationships between the feedwater heaters, the steam

turbine and the condenser indicate that degradation at one point in the steam

cycle will cause changes in the measured (and expected) performance all

around the steam eycle. The expected TTD of any feedwater heater is

Foreword

dependent upon the performance of the remainder of the steam cycle

equipment. It is necessary to perform a heat balance analysis (step | above)

to quantify these interrelationships. Then an expected equipment

performance calculation (step 2 above) can predict the expected output from

each feedwater heater given the performance of other equipment in the

plant

In the case of the degraded feedwater heater, the expected TTD of the higher

pressure feedwater heater will be higher when the lower pressure feedwater

heater is degraded than it would be if the lower pressure feedwater heater is

not degraded. If the monitoring system assumes a “target” TTD for a

feedwater heater that doesn’t depend upon the performance of the other

feedwater heaters, it is assuming that a higher pressure feedwater heater will

make-up any degradation in the lower pressure feedwater heaters. This is

equivalent to assuming that the “rubber” (design analysis) model of the

plant is an accurate prediction of the expected equipment performance.

The one remaining problem with the performance analysis described above

is that the expected performance prediction is based on a design model that

might not represent the actual performance expected for plant equipment.

One way to resolve this is to obtain data from early in the plant operational

history when degradation can be consicered to be zero. Use this plant data

as the design data in the plant design aralysis model instead of vendor

design or guarantee data. This “tuning” or “base-lining” process can be

repeated at any time during the life of the plant: use measured plant data as

the plant design data such that the plant degradation is zero at the time of the

measured data,

An on-line performance monitoring system should be thought of as a

relative evaluation instead of an absolute evaluation. Because plant

measured data does not normally come from calibrated, precision-test

instruments, the absolute magnitude of the results may not be accurate.

However, on-line performance monitor:ng systems can be very good at

detecting changes in performance.

Because an on-line performance monitcring system produces relative

results, the degradation of plant equipment must be tracked over time to

identify changes that have occurred. For this reason, itis important to install

a performance monitoring system early in the operational history of the

plant. Any performance changes that occurred before the monitoring system

‘was installed at the plant may be missed by the monitoring system.

The only way I would be able to tell my PG&E manager about degradation

in the feedwater heaters would be to run earlier measured data through the

performance monitoring calculation described above, and then compare the

Foreword

degradation calculated from the earlier time to the degradation calculated

from the current plant measured data. The changes in calculated degradation

are an accurate indication of changes in equipment performance, but the

absolute values of the degradation may not be accurate.

Rodney R. Gay

Foreword

Foreword

1. Overview of Performance Monitoring

1.1 Concept of Performance Monitoring

1.1.1. “Where You Are” Versus “Where You Should Be”

Performance monitoring is the process of continuously evaluating the

production capability and efficiency of a power plant and its equipment over

time using measured plant data. Performance monitoring evaluations are

repeated at regular intervals using data readily available ftom on-line

instrumentation. This differs from a performance test, a one-time event that

relies on precision instrumentation installed specifically for that test.

The objective of performance monitoring is to continuously evaluate the

degradation (decrease in performance) of the plant and its equipment in

order to provide plant operators additional information to help them identify

problems, improve performance, and make economic decisions about

scheduling maintenance and optimizing plant operation. A successful

performance monitoring system can tell plant operators how much the plant

performance has changed and how much each piece of equipment in the

plant contributed to that change. This information enables operators to

localize performance problems within the plant and to estimate the

operational cost incurred because of the performance deficits.

While it is expected that performance monitoring will help operators

diagnose and repair faults in plant equipment, the diagnostic procedures to

accomplish this are beyond the scope of this book.

To answer the question “How good is my performance?” one must compare

the current capability of the power plant and its equipment to its expected

capability. Thus, performance monitoring is a comparison of the current

capability, “Where You Are”, to the exnected capability, “Where You

Should Be”.

Production capability is a measure of tke ability of equipment to produce the

output that the equipment is designed to produce; it is not the current

production. In other words, a plant that is designed to generate (produce)

600 MW, might only be able to generate $50 MW on a hot day, but still be

capable of generating 600 MW when operating at its design conditions. The

objective of performance monitoring is to continuously evaluate this

capability and monitor its change over time.

Degradation is defined as the shortfall in equipment performance caused by

‘mechanical problems in the equipment (such as wear, fouling, and

page 13 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

oxidation), but not by changes to set points under the control of the plant

operators. For example, if plant operators increase the excess oxygen on a

coal-fired boiler to reduce CO emissions when burning low quality fuel, the

boiler efficiency will decrease. The boiler capability has not changed: if the

fuel and excess oxygen level were returned to their original value, the boiler

efficiency would also improve to its original value. Thus, the observed

efficiency decrease in this example is not degradation, but is instead an

opportunity for economic optimization.

A second example is a gas turbine whose water-to-fuel injection ratio must

be increased to meet more restrictive NOX emissions requirements. The

engine power would increase and the heat rate would get worse (increase).

These changes in performance do not represent degradation, just a change in

operating conditions.

Economic optimization is concemed with finding the plant operating mode

and control set points that meet all constraints on plant operation (such as

equipment protection and emissions limits) and maximize plant profits. The

current degradation of plant equipment is an important input to optimization

analysis and the current plant control set points are important inputs to

degradation analysis, but the two are separate evaluations.

Performance monitoring involves two calculations: current production and

expected production. The evaluation of performance degradation is a

comparison between these two values. For example, a plant designed to

produce 600 MW on a 59 F day may be expected to produce 550 MW on a

100 F day. If the plant meets its expected production of 550 MW on the 100

F day, then its performance is as expected (zero degradation) even though it

did not perform at its design production level of 600 MW.

Table 1-1 lists the plant equipment types discussed in this book, the

production objective(s) of each equipment type, and an output parameter

that is a measure of each production objective. Any performance evaluation

of the equipment listed in the table must relate the current production

capability of the equipment to the expected production capability. Notice

that the equipment types that consume fuel have two production objectives,

and hence two measurements of performance. This is because output and

efficiency are independent parameters for these equipment types. For fuel-

consuming equipment, efficiency needs to be evaluated along with output

production capability because it may be possible to achieve higher output by

simply consuming more fuel.

For other equipment types (non-fuel-consuming types such as heat

exchangers and steam turbines), the input source of energy is fixed (that is,

not determined by the performance of the equipment type being monitored)

1.Concept of Performance Monitoring page 14

and therefore higher efficiency causes higher output. Thus, for these

equipment types output and efficiency are not independent performance

parameters,

Table 1-1 List of equipment types and their production objectives

Equipment Production Objective

Measured Output

Electricity

Power Plant

Efficiency

Efficiency

Net Power (MW)

Net Heat Rate

Heat Rate

Steam Generation

Steam Flow(s),

Steam Turbine

Electricity

Boiler Temperature(s) and

Pressure(s)

Efficiency Boiler Efficiency

Heat Recovery Steam | Steam Generation Steam Flow(s),

Generator ‘Temperature(s) and

Pressure(s)

Condenser Vacuum Condenser Shell Pressure

Cooling Tower Energy Rejection Cooling Water Temperature

to Condenser

Feedwater Heater Feedwater Heating Feedwater Outlet

Temperature

‘The performance of a power plant has two measures: power and heat rate.

‘They are independent measures of peiformance in that the highest power is

not necessarily achieved at the best (lowest) heat

rate. A plant operator

generally has the option to control the plant for maximum power output or

to control for maximum efficiency. A performance evaluation of a power

plant must include evaluations of both the power generation capability and

the heat rate capability.

page 1 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

A gas turbine is like a power plant; in ‘act, a simple-cycle gas turbine is a

power plant. Thus, both power and heat rate are independent performance

parameters that must be evaluated when monitoring a gas turbine.

A boiler consumes fuel to generate steam. Both the’steam generation

capability and the boiler efficiency are important parameters of boiler

performance, and both must be evaluated.

The job of a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG) is to convert the

available exhaust gas energy into as much steam as possible. When the plant

is operating at full load, the temperature and pressure of the steam are

controlled by the plant, and therefore are not independent parameters of

HRSG performance. They represent requirements that the HRSG must meet.

Improved HRSG effectiveness or efficiency results in increased steam

generation. There is no opportunity to increase steam generation capability

without increasing HRSG efficiency; thus, efficiency and steam generation

are not independent parameters of performance. A performance monitoring

system must compare the current value of HRSG steam generation or

efficiency to its expected value.

‘A condenser’s job is to condense all of the steam exhausted from the steam

turbine at a pressure as low as possible. The need to condense alll of the

steam is a requirement that must be met. Condenser pressure is the measure

of condenser performance: the lower the pressure the better the

performance. A performance monitoring system must compare the current

value of this pressure to its expected value. Other parameters of condenser

performance, such as cleanliness, are only important because they are an

indication of the ability of a condenser to reduce steam turbine exhaust

(condenser) pressure to its expected value.

A cooling tower must reject all of the steam condensation energy (condenser

duty) to the cooling media (air or water). The quantity of energy to reject is

a requirement that the cooling tower must meet. The measure of

performance of a cooling tower is the cooling water temperature at the exit

of the cooling tower (or at the inlet to the condenser). A lower value of thi

temperature indicates better performance. A performance monitoring system

must compare the current value of this temperature to its expected value,

1.1.2 Performance Calculation Procedure

Performance monitoring involves a calculational procedure that is repeated

at regular time intervals. The details of the calculation vary greatly from

plant to plant, depending upon the measured data that is available, the plant

type, and the degree of sophistication cf the calculations. However, a

1. Concept of Performance Monit page 16

performance monitoring calculational procedure always involves some or all

of the following steps:

1. Acquire measured data.

2. Review, check and/or validate the raw measured data to find errors

and omissions.

3. If possible, fix errors or omissions identified in the measured data.

4. Improve precision of the measured data by averaging and/or other

techniques.

5. Compute fluid thermal properties, such as enthalpy and entropy,

from measurements.

6. Use mass, energy and/or chemical balances to calculate data that is

not measured, but can be computed from the measurements that do

exist.

7. Compute current values for equipment parameters of performance

such as heat rates, efficiencies, effectiveness’s, temperature

differences, and cleanliness.

8. Predict expected values for equipment parameters of performance.

9. Compute the corrected performance of the plant equipment

10. Calculate the shortfall in performance (degradation), based upon the

difference between the expected and current values of the

performance parameters.

11, Estimate the effect (impact) that the equipment degradation has on

plant performance and plant operating cost.

12, Perform plant optimization calculations to predict the most cost-

effective way to run the degraded plant equipment.

A given performance monitoring system often will not perform all of these

calculational steps, but the list is a fairly complete compilation of the

calculations that can be and probably should be done in a comprehensive

and successful performance monitoring system.

1.1.3. Expected Performance: “Where You Should Be”

For performance monitoring to be meaningful, one must compare current

performance to expected performance, and track that comparison over time.

This process is equivalent to tracking degradation (the difference between

expected and current performance) over time. Since performance

monitoring is a continuous process, as opposed to a one-time event like a

page17 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

performance test, the performance evaluation will be performed over a

variety of plant operating conditions. This makes the evaluation of expected

performance the most challenging aspect of performance monitoring.

Figure 1-1 illustrates the concept of expected versus actual (degraded)

power for a gas turbine engine. The baseload power of a gas turbine engine

varies with inlet air temperature, as illustrated by the expected power line in

this figure. It is assumed for the purposes of this discussion that ambient

temperature is the only environmental parameter that is changing, Gas

turbine vendors typically provide performance curves which show how

performance will change with environmental conditions. A vendor

performance curve can be used to compute the expected power line. Notice

that one point on the expected power line is the rated power, which occurs

at only one air inlet temperature (shown as Trefeence in Figure 1-1).

When a degraded gas turbine is operated over a range of inlet air

temperatures, the measured gas turbine power levels will likely be along a

line below the expected power line, as illustrated in Figure 1-1.

The corrected power is the power that the actual (degraded) engine would

produce if operated at the reference temperature. The difference between the

tated and corrected power is the degradstion of the engine from rated.

The procedure to calculate expected performance is to start with the

expected performance at the reference operating conditions (the rated

performance), and then use a model or models of equipment performance to

predict the change in equipment performance when the equipment is

operated at conditions different from the reference operating conditions. The

‘model(s) of equipment performance can be very simple, such as table look-

ups, or very complex, such as a physically based computer code.

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 18

Performance Evaluation Terms

GT Power

Expected (ne degradation)

Expected

Performance

‘Actual

Performance

rae Trotoane Inlet Temperature

dooF

Figure 1-1, Comparison of rated, expected, measured and corrected power for a

gas turbine

The expected performance line in Figure 1-1 is actually a simple example of

a performance model of a gas turbine. This line shows how gas turbine

power will change as the gas turbine inlet temperature changes. This line

could be converted into a table look-up as part of a computerized

performance model.

Of course, any gas turbine performance monitoring system must also

account for changes in other reference operating conditions such as inlet

pressure loss, exhaust pressure loss, fuel properties, inlet pressure, inlet

relative humidity, steam/water injection, inlet guide vane angle and firing

temperature. Since these are independent parameters of gas turbine

performance, separate models can be used for each condition, and the total

power change is the product of the power changes predicted from the

changes in each reference operating condition. Using curves to evaluate

equipment performance is discussed later in this chapter under “Curve-

Based Methods”.

page19 1, Concept of Performance Monitoring

An alternative model of gas turbine performance is a computer code that

includes physically based mathematical models of the compressor,

combustor and expander. Such a code would take the operating conditions

as inputs and predict the gas turbine power and heat rate at those operating

conditions. It would be necessary to adjust (tune) such a computer code so

that it accurately predicts the gas turbine rated performance at the reference

operating conditions, Then the performance monitoring system could input

‘measured data into the computer code to predict the expected performance

at the current measured operating conditions. Using physically based

computer models to evaluate equipment performance is described later in

this chapter under “Model-Based Performance Analysis”.

1.1.4 Equipment Ratings

The rated performance of plant equipment must include a specification of all

the external conditions and control settings that change equipment

performance but are not part of the equipment itself. Table 1-1 lists all of the

specifications that are required to state the rating of a gas turbine.

‘There are several ways to obtain the rating data for a plant and its

equipment. For performance monitoring purposes, the choice is somewhat

arbitrary since a monitoring system tracks changes in performance or

degradation over time. If the monitoring system defines degradation as the

fall-off in performance over time, the absolute value of the rating cancels

‘out. Several ways to define equipment ratings are:

‘© Use vendor guarantees

© Use acceptance test (as-built) data for the plant and equipment

‘* Use plant measured data at the time the monitoring system is

installed

© Baseline (tune) the ratings on a regular basis using plant measured

data

A gas turbine will produce its rated power and heat rate only at the reference

operating conditions listed. The values of the reference operating conditions

are called the reference data. All of the data in Table 1-2 are related. Change

any of the operating conditions (from their reference values), and the power

and heat rate of the engine will change (from rated),

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 20

Table 1-2 Typical rating specifications for a gas turbine engine

Gas Turbine Rating Specifications Example Data

RATING:

Gross Power 170oMw

Gross Heat Rate 9400 BewKW-hr

REFERENCE OPERATING CONDITIONS:

Ambient Temperature 59 deg-F

Ambient Pressure 14.65 psia

Ambient Specific Humidity 0.0065

Ibm H,0/lbm air

Inlet Pressure Loss 4 in H,0

| Exhaust Pressure Loss 12 in HO

‘Steam/ Water Injection none

Fuel Type Natural Gas

| Fuel Lower Heating Value 20200 Brw/lbm

Inlet Guide Vane Angle 86 deg,

Firing Temperature 7300 deg-F

Inlet Cooling or Heating none

The expected performance prediction for a gas turbine, or for any equipment

type, requires both a set of rating specifications (which includes both the

rated performance and the reference operating conditions), plus a model of

performance that predicts how performance changes as the operating,

conditions change.

Table 1-3 lists the rating specifications for a typical heat recovery steam

generator.

page2l 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

Table 1-3 Typical rating specifications for a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG)

Heat Recovery Steam Generator Example Data

Rating Specification

RATING:

HP Steam Flow 415,000 lb/hr

IP Steam Flow 70,000 liar

REFERENCE OPERATING CONDITIONS:

Exhaust Gas Flow 3,250,000 Ilr

Exhaust Gas Temperature 1138 F

Exhaust Gas Composition 3% HO

HP Drum Pressure 1900 psia

IP Drum Pressure 400 psia

LP Drum Pressure 100 psia

Inlet Feedwater Temperature 140F

HP Steam Temperature 1100 F

Duct Bumer Fuel Flow none

Steam Extraction to Process 20,000 Ilar

Water Extraction to Process 30,000 tar

Once again, the rating specifications for an HRSG indicate that the HRSG

will produce the rated steam flows only if it is operating at the reference

‘operating conditions. To predict HRSG expected performance, a monitoring

system must be able to predict the change in HRSG performance as

operating conditions change from their reference values.

Table 1-4 gives typical rating specifications for a steam turbine.

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 22

Table 1-4 Typical rating specificaiions for a steam turbine/generator

Steam Turbine Rating Specification

T

Example Data

RATING:

Gross Power 190 Mw

REFERENCE OPERATING CONDITIONS:

Throttle Steam Flow £930,000 Ibrar

Throttle Steam Temperature 137F

Throttle Steam Pressure 1800 psia

Condenser Back Pressure 0.8 psia

Reheat Steam Temperature 1000 F

UP Extraction Flow none

LP Admission Flow 160,000 tbrhr

A steam turbine will generate its rated power only at the rated steam flow

conditions and condenser pressure. Any change in these flow conditions or

pressures will cause the steam turbine power to change.

page 2! 1. Concept of Perfarmance Monitoring

‘Table 1-5 Typical rating specifications for a condenser

Condenser Rating Specification Example Data

RATING:

Shel (Steam) Pressure 0.8 psia

REFERENCE OPERATING CONDITIONS:

Inlet Steam Flow 930,000 tbrhr

Inlet Steam Enthalpy 1000 Brullb

Cooling Water Flow 6,000,000 Ibe

Cooling Water Inlet Temperature 80F

‘A condenser is required to condense all of the incoming steam and transfer

the energy released from condensation to the cooling water. The condenser

duty, the cooling water flow and the cooling water inlet temperature are

‘imposed upon the condenser by the performance of other equipment in the

plant (external to the condenser). The condenser is designed to achieve its

rated pressure at a given (reference) set of inlet flow conditions. Any change

in the inlet steam or water flows will be expected to change the condenser

pressure.

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 24

Table 1-6 Typical rating specifications for a coal-fired boiler

Boiler Rating Specification

Example Data

RATING:

Main Steam Generation 2,560,000 tbvhr

Boiler Efficiency 89.59%

REFERENCE OPERATING

CONDITIONS:

Fuel Input Energy 3374 mmBtwhr

‘Steam Drum Pressure 2800 psig

Steam Temperature 1005 F

Reheat Steam Temperature 1005 F

Reheat Steam Flow 2,275,000 lb/hr

Reheat Steam Inlet Pressure 592 psig.

Fuel Higher Heating Value 11,495 Bru

Fuel Composition (C, H, N, $, HO, Ash)

(64.2,4.1,25,4.4,08,4.1,19.9)

Inlet Feedwater Temperature 475 F

Inlet Air Temperature 80F

Inlet Air Relative Humidity 60%

page 2S 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

Table 1-7 Typical rating specications for a feedwater heater

Feedwater Heater Rating Specification Example Data

RATING:

Outlet Feedwater Temperature 420F

Outlet Drain Water Temperature 380F

REFERENCE OPERATING CONDITIONS:

Inlet Steam Flow 120,000 lbvhr

Inlet Steam Temperature 890 F

Inlet Sieam Pressure 320 psia

Inlet Feedwater Flow 2,600,000 lb/hr

Feedwater Inlet Temperature 370F

Inlet Drain Water Flow 150,000 tbr

Inlet Drain Water Temperature 460 F

1.1.5 Corrected Performance: The Indicator of

Degradation

For combined-cycle power plants, the expected performance varies greatly

over time. This makes it difficult to track changes in performance, as the

measured values of most performance parameters vary due to changes in

plant operating conditions. One methodology to make the identification of

performance changes over time easier is to “correct” the current

performance to a standard operating condition, usually the reference

operating conditions. To correct the performance means to account for the

performance variations that would be expected due to the changes in

environmental conditions and control set points. The corrected performance

is the performance that would be expected if the current (degraded) engine

were operating at the reference operating conditions. The virtue of corrected

performance is that its expected value zemains constant and equal to the

rated value. Thus, any change in a corrected value represents a change in

equipment performance capability

1.Concept of Performance Monitoring page 26

Corrected power is a barometer of engine performance. It goes down when

degradation increases and it goes up when degradation decreases. In fact,

the degradation in performance from one point in time to another is equal to

the change in corrected performance over that time range.

a

||

ef —___ i

Figure 1-2 Measured and corrected gas turbine power over a nine-month time

period. An overhaul was performed on the gas turbine during October 2002; this

time period is evident on the plot as the time during which there is no measured

data

Corrected gas turbine power accounts for changes in engine operating

conditions and predicts the equipment performance if the equipment were to

operate at the reference operating conditions (including inlet filter delta-P,

ambient conditions, load level, water/steam injection, fuel heating value,

and exhaust delta-P). If changes in the engine operating conditions were to

‘cause changes in gas turbine power, the corrected power would not change.

Figure 1-2 is an actual trend of gas turbine measured and corrected power.

The measured power is shown on the plot only when the engine was

operating at or above 99% percent of baseload power. Notice that measured

page27 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

baseload power varies during each day, and is higher in the winter months

than in the summer months.The trend display of measured power is a history

of operation, but gives the viewer little information about degradation,

Each corrected power point shown in Figure 1-2 is an average of calculated

corrected power over a time period of approximately two hours. Corrected

power is a prediction of the power that the engine would generate if

operating at reference operating conditions. Itis essentially the current,

rating of the engine, or it is a prediction of the power the engine would

achieve in a performance test at reference operating conditions.

The corrected power is a convenient plotting parameter because it shows

degradation in the engine. Notice that the engine corrected power started at

over 161 MW in July and degraded to approximately 158 MW by October, a

loss of approximately 3 MW over a three-month period. The engine

‘overhaul in October improved the corrected power back up to approximately

162 MW. In other words, this plot shows that the overhaul improved the

engine's power capability by 3 MW to 4 MW.

Figure 1-3 Shows corrected condenser pressure over an eight-month period

Figure 1-3 shows corrected condenser pressure at a combined-cycle power

plant in the United Kingdom. Notice the slow increase in corrected pressure

‘over 150 days, indicating fouling of the condenser tubes and/or blockage in

the waterboxes. Cooling water flow through the tubes also decreased about

4% during this time period (not shown on the figure). When the tubes and

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 28

waterboxes were cleaned during a plant outage, the corrected condenser

pressure improved back to approximately the same level as the beginning of

the trend, and the cooling water flow rate also recovered (not shown on the

figure)

4.1.6 What is My Degradation?

Degradation is the reduction in equipment performance capability that has

occurred over time. It is a relative parameter; it compares equipment

capability at one point in time to that at another time. Since the corrected

gas turbine power is a prediction of the current rating of the engine, the

difference in corrected power from one point in time to another is the

degradation that has occurred over the time period. Thus, degradation may

be defined as the change in corrected performance over time.

For the value of degradation to be meaningful, the start time and end time of

the degradation must be stated. If no time range is stated, it is usually

assumed that the degradation is over the operational lifetime of the

equipment, which is from the time the equipment was put into service to the

present.

Often when historical data is not available, degradation may be stated as the

difference between the current equipment capability and its rated capability.

This is equal to the difference between the rated performance and the

corrected performance. Since degradation is defined as a change in

performance over time, this definition of degradation is only true if the

equipment actually achieved its rated performance at some point in time.

Rated performance is often set equal to the vendor guarantee as opposed to a

performance test at the beginning of equipment life. Thus, the equipment

‘may not have ever operated at its rated performance.

Degradation will be defined throughout this book as the difference between

corrected and rated performance. Ideally, the rated performance should be

defined as the actual performance at some given point in time, but if

sufficient plant data is not available it may be set equal to the vendor

guarantee.

The definition of degradation as a change over time instead of the change

from vendor guarantee is significant to the concept of performance

monitoring because a change over time is an aid in identifying changes in

equipment performance, while a change from guarantee may be misleading.

If the degradation is defined as the change from guarantee (a level of

performance that the equipment may never have actually operated at), some

plant equipment may show may show negative degradation, indicating that

the equipment is performing better than the guarantee level.

page29 1, Concept of Performance Monitoring

1.1.7 How Much is Degradation Costing Me?

Knowing the amount of degradation is important, but it’s not the full story. '

In order to make decisions about which maintenance to perform, plant

operators need to know how much the degradation is costing plant

operation.

For example, a reduction in gas turbire performance (power and heat rate)

has an effect on overall combined-cycle plant performance, which can be

calculated using an overall plant model. The power reduction in the gas

turbine reduces plant power because both the gas turbine and the steam

turbine power levels will change. The steam turbine power changes because

the gas turbine exhaust flow and temperature normally change as a result of

the gas turbine degradation. The heat rate increase of the gas turbine will

cause the plant to consume more fuel per MW-hr of power produced. These

effects on plant power and heat rate can then be converted to operating costs

by applying a fuel cost to the extra fuel being burned, and/or a MW-hr cost

to the power which is not being sold because of the degradation.

Here isa situation where the definition of degradation as a change in

performance over time, as opposed toa change from vendor guarantee, is

particularly important. Once the plant is accepted and goes into commercial

operation it is too late to worry about equipment guarantees. The best that

the operators can be expected to do is to maintain plant performance at a

level that the plant actually operated in the past. Therefore, degradation is an

estimate of the performance improvernent that is possible, and any existing

degradation can be looked upon as the source of an operational cost that is

potentially avoidable.

Degradation normally is evaluated in different engineering units for each

‘equipment type: gas turbine degradation is in MW while condenser

degradation is in either psia or percent cleanliness. This makes it difficult to

compare degradations calculated for cifferent parts of the plant or for

different equipment types. One way to make a meaningful comparison is to

calculate the impacts of the degradation on overall plant power, heat rate

and operating cost. The definition of z plant impact is the change in plant

performance that would be realized if the degradation were to be returned to

zero by some maintenance action.

For example, a condenser may have a degradation of 0.1 psia (6.9 mbar).

This means that the condenser is operating at a pressure 0.1 psi (0.69 mbar)

higher than it would operate if the degradation were zero. This degradation

causes a reduction in steam turbine power, which is also a reduction in plant

power. The impact of the condenser degradation on plant power is equal to

the change in plant power caused by the degradation of the condenser.

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 30

The reduction in plant power due to the condenser degradation increases

plant heat rate since fuel flow is not changed, Actually, fuel flow ina

Rankine cycle plant with condenser degradation may decrease slightly

because the increased condenser pressure will lead to higher feedwater

temperature entering the boiler, which will reduce boiler fuel consumption.

Even so, the plant power always decreases and heat rate always increases

when condenser pressure increases. The change in plant heat rate caused by

the degradation in the condenser is called the impact of condenser

degradation on plant heat rate.

‘These changes in plant performance reduce electric sales revenues and

increase fuel costs, resulting in a net operating cost to the plant. The change

in plant revenues minus fuel costs is called the impact of condenser

degradation on plant cos

‘The idea behind the overall plant impacis is to convert all of the

degradations in the plant to their respective costs on plant performance.

Then these degradations can be compared and evaluated on a consistent

(apples to apples) basis. Table 1-7 belov’ illustrates the concept for a

combined-cycle plant.

Table 1-8 Example of plant equipment degradations and their impacts on plant

performance

Impact on Plant Performance

Equipment | Degradation

Power | Heat Rate | Operating

(MW) | Btwkw-h) | Cost

(S/hr)

Inlet Air Filter | 1.1 in-tt,0 03 16 46

Gas Turbine 19MWw 22 15 294

HRSG 12,000 tbe 4 169

Steam Turbine | 0.8 MW 08 31 84

Condenser O41 psi oa 25 56

Cooling Tower 21F 02 B 2

Total Plant 31 191 on

page 31 1, Concept of Performance Monitoring

‘The inlet air filter in Table 1-8 has a pressure-loss degradation equal to 1.1

in-H,0. If this degradation were eliminated by replacing the air filters, the

‘gas turbine inlet pressure would increase, resulting in a gas turbine power

increase, The steam turbine power would also increase because of the

increase in gas turbine exhaust energy. The total plant power would increase

by 0.3 MW, which is defined as the impact of the air filter on plant power.

This plant power increase would cause a plant heat rate decrease equal to 16

BtwkW-hr. Overall these changes in plant power and heat rate would yield a

net increase of 46 $/hr in plant operating profits (electric sales revenues

minus fuel costs). Methods to calculate these impacts are reviewed in the

chapter 6, “Impacts of Degradation on Overall Plant Performance”.

The total plant power degradation is equal to the sum of the equipment

impacts on plant power. In other words, the total of the equipment impacts

on plant power is equal to the degradetion in plant power, which is equal to

the rated plant power minus the corrected plant power, when the degradation

is calculated from rated. For example, if the plant were rated at 400 MW,

and the total power degradation from rated is 5.1 MW. Then, the plant

‘would be expected to now produce orly 394.9 MW if operated at the plant

reference operating conditions. This power (394.9 MW) is called the

corrected plant power.

Ina similar manner, the corrected plant heat rate is equal to the rated plant

heat rate plus the total of the equipment degradations in plant heat rate (191

Btu/kW-hr in Table 1-8). The current plant operating costs (electric sales

revenues minus fuel costs at the reference operating conditions) are S671/hr

higher than they would be if the plant was performing as rated and was

operating at the reference operating conditions.

1.1.8 Optimization: “Where You Could Be”

Once the degradation of the plant and its equipment is known, the plant

operator is prepared to answer the question, “What is the best way to operate

the plant so as to maximize plant profits?” The idea is to adjust the plant set-

points that are under the control of the operator to make as much money as

possible for the plant. The equipment degradation listed in Table 1-8

summarizes maintenance issues, but optimization is concemed with actions

the operator can take to improve performance without maintenance.

‘An example of calculated optimization outputs for a combined-cycle power

plant with two gas turbines is illustrated in Table 1-9.

1. Concept of Performance Monitoring page 32

Table 1-9 Example optimization outputs for a combined cycle power plant

Controllable Current Value | Optimal Cost Savings

Set-point Value (Shr)

GTI Power 170 MW limw | 90

GT2 Power 150 MW 159 MW 88

Inlet Chiller #1 On oft 2

Inlet Chiller #2 on on u

Duct Burner # on on o

Duct Bumer #2 om on 0

Number of Cooling, 7 6 au

‘Tower Fans On

‘Total Savings Possible 22

The Current Value column shows current plant operating data, and the

Optimal Value column shows where the plant could operate if the operator

took the appropriate control actions. Finally the Cost Savings column

‘estimates the increase in plant operational profit that would be achieved if

the operator took the suggested actions. This screen is different from the

degradation screen in Table 1-8 in that no maintenance actions are required,

and the optimal operating conditions are achievable by operator action. No

one knows if the degradation in Table 1-8 is fully recoverable, but the

control actions suggested in Table 1-9 can be taken (assuming no

environment or other operational limit on plant operation is violated), and

the cost savings achieved.

4.1.9 Controllable Loss Displays

Controllable loss displays are an alternate way to present the degradation

and optimization data of tables 1-7 and 1-8. These displays are most often

used for Rankine cycle plants where the expected or target values of plant

performance parameters do not vary widely with plant operating conditions.

Controllable loss displays show the current value of selected plant

performance parameters, their target values, and the cost incurred by not

operating the plant at these target values.

pige33.— 1, Concept of Performance Monitoring

anes opzosebn (ilemarowasumtossisomunyitinf omoes Loto vm son?

oeey oe sess on i226

we 4 4P AP ae Se Se Se

207] pe ET

om eE JE IE 4

anor wom | [Cz] [Cae sere] [Caene

‘wey ""(oronw

Figure 1-4 Example controllable loss display for a fossil (Rankine cycle) plant

The advantage of controllable loss displays is that they are readily

understandable summary of the plant performance status. If there is no

degradation in plant equipment, the controllable loss display will show

small losses and vice versa. The disadvantage is that they give little

information as to the location of plant performance problems. Controllable

loss displays are a very useful way to summarize plant status; they inform

the operator if there is a plant performance problem.

The target values for controllable loss displays are generally based upon

expected overall plant performance with no equipment degradation

anywhere in the plant. Due to the regenerative nature of a Rankine cycle,

degradation in one area of the plant will likely show up as deviations in

several controllable loss parameters calculated from measured data in other

areas of the plant. Thus, controllable loss parameters do not report

degradation specific to individual plant equipment, but instead report a

departure in overall plant performance from the values that the performance

parameters would have if the entire plant were “new and clean”,

For example, in order to achieve the target main steam temperature in a

boiler, the economizers, the air preheater, and the feedwater heaters must all

1.Concept of Performance Monitoring page 34

operate with their target performance. Degradation in any of these may

cause the steam temperature to change. A change in the steam temperature

may change the throttle pressure, which might change the steam turbine

efficiency and the condenser pressure. Thus, many of the controllable loss

parameters are related to each other, and several will likely change when

one of them changes.

The target values used in controllable loss displays are a very different

concept from the equipment degradation calculations described above where

the expected performance of each equipment type depends upon the

operational conditions that the equipment is exposed to and is independent

of the degradation of other equipment in the plant.

1.2 ASME Test Codes

ASME Performance Test Codes provide test procedures that yield results of

the highest level of accuracy consistent with the best engineering knowledge

and practice currently available, The test procedures were developed by

balanced committees of professional individuals representing all concerned

interests. The test codes specify procedures, instrumentation, equipment

operating requirements, calculation methods, and uncertainty analysis,

When tests are run in accordance with an ASME code, the test results will

be of the highest quality and the lowest uncertainty available,

The focus of the ASME test codes is to provide test specifications

appropriate for verification of compliance with guarantee or warranty

performance. As such, the absolute eccuracy of measured performance is,

stressed as opposed to ease of testing. In general it is very difficult to

implement the AMSE test code procedures as the basis of performance

monitoring at an operating power plant.

The following table lists the test codes that are most closely related to power

plant performance monitoring.

page 35 1. Concept of Performance Monitoring

Table 1-10 ASME Performance Test Codes closely related to pefformance

monitoring

ASME Test Code Description

PTC 1 - 1999 General Instructions

PTC 2- 1980 (R197)

Code on Definitions and Values

PIC 4.3 ~ 1968 (R191) Air Heaters

PTC 4.4 1981 (R2003) Gas Turbine Heat Recovery Steam

Generators

PIC6- 1996 Steam Turbines

PTC 6A - 2000 Appendix to PTC 6

PTC 6 Report 1985 (R1997)

Evaluation of Measurement Uncertainty in

Performance Tests of Steam Turbines

PTC 6S ~ 1988 (R195)

Procedures for Routine Performance Test of

‘Steam Turbines

PTC 82-1990

Centrifugal Pumps

PTC 11 ~ 1984 (R198)

Fans

PTC 12.1 -2000 Closed Feedwater Heaters

PIC 12.2- 1998 Steem Surface Condensers

PTC 123 - 1997 Deaerators

PTC 19.1 - 1998 ‘Test Uncertainty

PTC 22-1997 Performance Test Code on Gas Turbines

PTC 23 ~ 1986 (R197)

Atmospheric Water Cooling Equipment

PTC 46~ 1997

Overall Plant Performance

PTC PM~ 1993

Performance Monitoring Guidelines for

‘Steam Power Plants

1, Concept of Performance Monitoring

page 36

1.3. Performance Testing versus Online Monitoring

A performance test is a one-time evaluation of equipment performance that

relies on precision instrumentation installed specifically for that test. The

equipment being tested is operated at conditions as close to design and/or

guarantee as possible. The objective of a performance test is to measure the

absolute capability of the equipment. The tests are often done to verify

vendor guarantees on new or upgraded equipment.

The objective of performance monitoring is to detect changes in equipment

performance (degradation) so that proper corrective action can be taken. The

absolute value of performance is not necessarily important to performance

monitoring; instead, repeatability of results is most important, so that

changes over time can be evaluated.

The principal differences between testing and monitoring are summarized in

Table 1-11 below.

Table 1-11 Comparison of performance testing and online monitoring

Performance Test | Online Monitoring

Objective ‘Absolute Performance Detect Degradation

Insiumentaion Type | Precision Test insiruments | Whatever Is Available

Measurement Requirement | Accuracy Repeatability

‘Test Interval One Time Event Repeated Often.

‘Test Conditions Equipment kolated and at | Normal Plant Operation

Full Load

The basic difference between performance monitoring and performance

testing is that monitoring uses whatever instrumentation is continuously

available at the plant to give the operators an indication of plant

performance status. As such, monitoring data is usually not adequate for

vendor guarantee testing, but is usually acceptable for tracking changes in