Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brown, Ch. 2 A "Methodical History" of Language Teaching, Pp. 13-38

Uploaded by

Cote Cabrera0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1K views14 pagesLanguage Teaching

Original Title

1. Brown, Ch. 2 a “Methodical History” of Language Teaching, Pp. 13-38

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLanguage Teaching

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1K views14 pagesBrown, Ch. 2 A "Methodical History" of Language Teaching, Pp. 13-38

Uploaded by

Cote CabreraLanguage Teaching

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by Principles: An interactive Approach to Language

Pedagogy. Second Exdtion, White Plains: Addison Wesley Langman, Ine,

_____cuapter 2

A“METHODICAL” HISTORY

OF LANGUAGE TEACHING

‘The first step toward developing a principled approach to language teaching will

tbe to tum back the clock about a'century in onder to leen from the histor

‘yeles and trends that have brought us tothe present day. After all ii fil ta

completely analyze the class session you just observed (Chapter 1) without the

backdrop of history: In tis chapter we focus on methous asthe identifying cha.

acteristics of a century of ‘modern’ language teaching efforts. What do we mean

by the term “method” by which we tend to characterize that history? How do

_methods reflect various trends of disciplinary thought? How does current research

fon language leaning and teaching help us to distinguish, in our history. between

passing fils and the good stuf? ‘These ae some of the questions we will address

in this chapter.

In the next chapter this historical overview culminates in 4 close look at de

‘current state ofthe atin language teaching. Above all you will come to sce hun

‘our profession is now more aptly characterized by a relatively unified, comprehen

sive “approach” rather than by competing, restricted methoxls. That_ gener

approach will be described in detail, along with some of the current profesional

Fangon associated with it

As you read on, you will encounter references to concepts, constructs, sues,

and models that are normally covered in a course in second language acquisition,

(S14), 1 am assuming that you have already taken or are currently taking such

course. If not, may I recommend that you consult my Principles of Language

Learning and Teaching, Fourth Edition (2000), or a book lke Mitchell and

Myles Second Language Leaning Tbeories (1998) that summarizes current topics

And issues in SLA. Throughout chis book 1 will refer here and there to speeied

chapters of my Principles book (PLLT) for background review or reading, should

you need it.

3

“

APPROACH, METHOD, AND TECHNIQUE

In the century spanning the mid18H0s to the mid-1980s, the languageteaching pro:

{ession was involved in a search, That search was for what was popularly called

“meth” oF ideally, a single method, generalizable across widely varying aude

‘ences, that would successfully teach students a foreign language in the classroom.

foreal accounts of the profession tend therefore to describe a succession of

methods, each of which is more of fess discarded as a new method takes its place

We will tun to that“ methodical history of language teaching in 4 moment but firs,

1We should try to understand what we mean by method.

What isa method?” About four decades ago Edward Anthony (1963) gave usa

definition that has admirably withstood the test of time, His concept of "method

vwas the second of three hierarchical elements, namely approach, metho, and tech

An approach, according to Anthony, was a set of assumptions dealing with

the nature of language, learning, and teaching. Method was described as an overall

plan for systematic presentation of language based upon a selected approach,

‘Techniques were the specific activities manifested in the classroom that were con

sistent with a method and therefore were in harmony with an approach as well,

‘To this dy for better or worse, Anthony's terms are sill n common use among

language teachers. A teacher may for example, atthe approach level. affirm the ult-

‘mate importance of learning in a relaxed state of mental awareness just above the

threshold of consciousness, The method that follows might resemble, sy

Suggestopedia (2 description follows in this chapter). Techniques could include

playing baroque music while reading a passage inthe foreign language, getting st

{ents to sit a the yoxa position while lstening to lis of words, of having learners

[adopt a new name in the classcoom and roleplay that new person

‘A couple of decades later Jack Richards and Theodore Rodgers (1982, 1986)

proposed reformulation of the coneept of “method” Anthony's approach,

method, and techaique were renamed, respectively. approach, design, and proce:

dure, with a superondinate term to describe this threestep process, now called

method.” A methox!acconting to Richards and Rodgers, was"an umbrella term for

the specification and interrelation of theory and pracice”J9R2:154). An approach

‘defines assumptions belief, and theories abou the nature of language and language

leaming, Designs specify the relationship of those theories 40 classtoom materials

and activities. Procedures ate the techniques and practices that are derived from,

‘one's approach and design.

TMi their reformulation Richards and Rexgers made two principal cont

butions to our understanding of the concept of method:

They specified the necessary elements of language teaching designs that had

heretofore heen let somewhat vague, Their schematic representation of

method (See Fig. 21) descebed sex important features of designs: objectives

Curie? A Meth” Hin of Language cing 15

ssllabus (rites for selectio

ter contend, activ

ind organization of linguistic and subject

les learner foes, teacher foles, and the role of instruc

‘ional materials, The latter three features have occupied a significant

proportion of our collective attention in the profession forthe list decade oF

0. Already in this book you may have noted how, for example, learner roles

(oes individual preferences for group or individual learning, student input

Jn determining curricular content, et.) are important considerations in your

teaching

2, Richards and Rodgers nudged us into at list reinguishing the notion that sep

anite, definable, discrete methods are the esential building locks of metho

‘ology. By helping us to think ia terms of an approach that underginds our

language designs curricula), which are realized by various procedures (tech

niques), we could see that methods, as we sill use and understand the term,

are too restrictive, too pre-programmed, and too prepackaged” Viraly all

languageteaching methods make the oversimplified assumption that what

teachers"do" in the elasseoom can be conventionalized ito set of proce

‘dures that fit all contexts. We are now all too aware that such is cle not

the ease,

As we shall see in the next chapter the whole concept of separate methods fs

no longer a central issue in languageteaching practice. Instead, we currenly make

ample reference to"methodology"as our superordinate umbrella term, reserving the

term method? for somewhat specific, entifable clsters of theoretically Compa

ible classroom techniques,

So, Richards and Rodgers's reformation ofthe concept of method was soundly

conceived: however thei attempt to give new meaning to an old term dk Hot atch

fom in the pedagogical teratre. What they wanted us to eall-methads more com>

forably referred to, I think, as-methodolog)”in order Wo avoid confusion with what

wwe will no doubt always think of as those separate entities (like Audilingual or

Suaaestopedi) that are no longer atthe center of our teaching philosophy

‘Another terminological problem isin the use ofthe term designs; instead, we

more comfortably refer to curicula or syllabuses when we refer to design featres

ff language program.

‘What are We left with in this lexicographic confusion? Its interesting that the

terminology ofthe pedagogical literature in the field appears to be more ia ine with

Anthonys original terms, but with some important additions and refinements.

Following ia set of definitions that reflect the current usage and that will be used

in this book,

Methodology: Pedagogical prctces in general (including theoretical under:

pinnings and related esearch), Whatever considerations are involved in “how £0

cach’ are methodological

ng

16 cwte2 AA Histo fangs Thing

Approach: Theoretically wellinformed positions and beliefs about the nature

of Tangvage, the nature of language learning, and the applicability of both to peda

opicalsetuings

Method: A generalized set of classroom specifications for accomplishing lin

ulstc objectives. Methods tend to be concerned primarily with teacher and se

dent roles and behaviors and secondarily with such features as linguistic and

subject matter objectives, sequencing and material. They are almost always thought

‘of as being broadly applicable wo a variety of audiences i a variety of contexts

4 Classroom techniques practices,

‘and behaviors observed when the

Curriculum/syllabus: Designs for carrying out a particular language pro

sam, Features include a primary concern with the specification of linguistic and

subject-matter objectives, sequencing, and materials to mect the needs of 2 desi

nated group of eamers in a defined context. (The term syllabus” usally used

‘more customarily inthe United Kingdom to reer to what i called a"cureicumin

the United States) |

teacher deters

Technique (also commonly referred to by other terms)” Any of awide variety

of exercises, activities, or tasks used in the language classroom for realizing lesson

objectives,

+ groupings that are commended

ral learmer have ovr

etd)

CHANGING WINDS AND SHIFTING SANDS

Agdance through the past century oF so of language teaching will give an interesting,

picture of how varied the interpretations have heen ofthe best way to teach a for

ign language. As disciplinary schools of thought—psychologs, linguistics, and

‘education, for example—have come and gone, so have linguage-teaching methods

‘waxed and waned in popularity. Teaching methods,28"approaches

‘course the practical application of theoretical ndings and postions,

288 ours that i relatively young, i should come

ore selec

The role ofintructional materiale

action are of|

na fel such

ho surprise to discover a wide

tse applications over the lst hundred years some in total philosophical

to others

Albert Marckwardt (1972:5) saw these “changing winds and shifting sands as,

‘cyclical pattern in which a new method emerged about every quarter ofa century

Eich new method broke feom the old ut took with i some of the positive aspects

ipo leming tsk et or leaner

See

4 The genera and specie otectives of the method

1. Asllabue model

%

There i curently ite an latermingling of such terms as “technique“task*proce

‘dure"activity? and "exercse"often usc in somewhat ice variation across the pote

‘on, OF these terms. ase fas received the most concerted attention, viewed by such

scholars as Petr Shan (19983) as mncorporating specific communicative aa peda

sogicil principles. Tisks, aceording to Ske an ethers, should he thought of ss

speci kind of technique ann fae, may actually inchade mote than one technique

See Chapter 3 fora more thorough explanation

os ioled i

cand cognite

be, Athoory ofthe nature of language

‘tage proiciney

2, Elomer

Ar account of thew

learning

4 A theory of native language

a

fof the previous practices. good example of this cyclical nature of methods is

found inthe “revolutionary” Audioligval Method (ALMD ¢a description follows) of

the midtwentieth century. The ALM borrowed tenets from is predecessor the

Dinect Method by almost haf « century while breaking away ehitely from) the

ammae Transition Method. Within a short time, however, ALM critics were

advocating more attention 10 thinking, to cognition, and to rue learning, which 0

Some smacked of return to Grammar Translation!

‘What follows isa sketch ofthe changing winds and shifting sands of language

teaching over the years

‘THE GRAMMAR TRANSLATION METHOD

A historical sketch of the lst hundred years of anguage-teaching must be set in the

context of a prevailing, customary languageeaching "tradition. For centusies, there

\were few if any theoretical foundations of language learning upon which to base

teaching methodology. In the Western world foreign’ language learing in schools

‘as synonymous with the learning of Latin of Greek. Latin, thought to promote

Imellectualy through “mental gymnastics was until relatively recently held to be

indispensable to an adequate higher education, Latin was taught by means of what

thas been called the Classical Method focus on rannnaical cule mrcntatho

‘vocabulary and of vasious declensions and conjigations, translation of text, doing

‘As other languages began to be taught in educational instcutions inthe eigh

teenth and nineteenth centuries, the Classical Method was adopted as the chict

means for teaching foreign languages. Litle thought was given at the

teaching someone how to speak the language: afterall, languages were not being

‘aught primarily to lean onl/aueal communication, but to learn for the sike of

being "scholarly" or in some instances, for gaining a reuling proficiency in foreig

language. Since there was litle if any theoretical rescarch on second language

acquisition in general or on the acquisition of reading proficiency, foreign languages

‘were taught as any other skill was taught

In the nineteenth century the Classical Method came to he known 38 the

Grammar Translation Method, There was little to distinguish Grammar

Translation from what had gone on fo foreign language clastooms for centuries

beyond a focus on grammatical rules a the basis fr translating from the second 0

the ative hinguage. Remarkably, the Grammar Translation Method withstood

atwemptsat the turn of the ewentieth century to"reform lnguageteaching metho

‘logy (see Gowin’s Series Method and the Direct Method, below), and to this day i

4s practiced in too many educational contexts. Prator and Celce Murcia (1979.3)

listed the major characteristics of Grammar Translation:

1. asses are taught nthe mother tongue, with litle active use of the target

langoae

Cowes? A Meth Hany of anguage Teaching 19

22, Much vocabulary is taught In the form of tits of isolated wor.

3. Long, elaborate explanations ofthe intsicacies of grammar are given

£ Grammar provides the rues for putting words together, and instruction often

focuses on the form and inflection of words

5. Reading of dificult classical texts is begun early

66. Lite attention is paid tothe content of texts, which are treated as exercives

fn grammatical analysis

+7. Often the only drills are exercises in translating disconnected sentences from

the target language into the mother tongue

8, Litle or no attention is ven to pronunciation

eine that this method has until very recemly been so stalwart among,

smany competing models Ht docs virtually nothing to enhance 4 students comms

tieative ay in the language. K fremembered with distaste by thousands of

‘Shoo! earners, or whom foreign language Hearing meant a tedious experience of

‘memorizing endless lise of unable amar rules and voeabulry and attempting

to prauce perfect fanstions of sited oe erry prose” (Richards & Rodgers

19863,

{nthe er nd ne can eran why Grammar Paso ens

popula I requres few specialize silo the part of teachers. ests of ran

Fis and of tanauons ae ean to cnsiact and can De object Sereda

“Candardzed tests of foreign langage stl do not attempt cpio communica

tive ates, so stents hve lle motivation to no beyond grammar analogs,

translations and fot exercises, Ants sometimes succesful in Kanga student

towan! a reaing knowledge of second langage But as Richards a Rogers

(Gao: 5) pointed out it has no advocates. I is4 method for which there i 90

theory. There is no erature that offers rationale or fesifiaton for itor that

SMtompus to relat it to sues in ings, poychology,o edvatonal theory” As

So contin to examine langageteaching methodology inthis book, think you

‘ilunersand mow fly the"iheory essen” ofthe Grammar Transation Method

GOUIN AND THE SERIES METHOD

“The history of “*moxler"foreign language teaching maybe sad to have begun in the

late 18008 with Frangois Gouin, a French teacher of Latin with remarkable insight.

History doest't normally credit Gouin as a founder of langusge-teaching method

tology because, at the time, his influence was overshadowed by that of Charles

Berlitz, the popular German founder of the Direct Method. Nevertheless, some

attention to Gouin’s unustally perceptive observations about language teaching

helps us to set the stage forthe development of languageteaching methods for the

century following the publication of his book, Tbe Art of Learning and Studying

Foreign Languages 40 1880.

20

Gouin had to go through a very painful set of experiences inorder to derive

his insights. Having decided in mide to learn German, he took up residency in

Hamburg for one year. But rather than attempting to converse withthe natives, be

engaged in a rather bizarre sequence of attempts to “master the language. Upon

aerval in Hamburg he felt he should memorize a German grammar book anda table

Of the 248 regular German verbs! He did this in a matter of only ten days, and hu

fed to “the academy" (he university) to test his new knowledge. “But als!” he

"wrote," could not understand a single word, nota single word! (Gouin 1880-11)

Gouin was undaunted. He returned to the solation of his room, this tine to me

lorize the German roots and to rememorize the grammar book an irewular verbs

Again he emerged with expectations of success. “Ibut alas. the result wis the

same as before. In the course of the year in Germany, Gouin memorized books,

translated Goethe and Schiller and even memorized 30,000 words in a German dc.

tionary, all in the isolation of his room, only to be crushed by his failure to unkler

stand German afterward, Only once dd he ty to"make conversation” as metho

but this exused people to laugh at hin, and he was too embarrassed to continue that

method. At the end of the year Gouin, having reduced the Classical Method #0

absurdity, was forced to return home, faire

But here wasa happy ending, After retaroing home, Gouin discovered that his

three yearold nephew had. during that yeae gone through the wonderful stage

Child Tanguage acquisition in which he went from saying virtually nothing at all (9

becoming a veritable chatterbox of French, Hove was i that this hile child suc

‘ceeded so casi in a first language, ia a task that Gouin in a second langage, had

found impossible? The child must hold the seeret to learning a language! So Gouin

spent. great deal of time observing his nephew and other childeen and came to the

following conclusions language learning is primarily a matter of tansforming pet

‘ceptions into conceptions. Chiliren use language to represent theie conceptions.

Language is a means of thinking, of representing the world to oneself (see PLZT.

CChapter 2). These insights, remember, were formed by 4 language teacher more

‘han a century ago!

So Gouin set about devising a teaching method that would follow trom these

Insights. And thus the Series Method was created, a metho that taught learners

ively (without translation) and conceptually (without grammatical rules and

explanation) a"series" of connected sentences that are etsy to perceive. The first

lesson of a foreign language would thus feach the following series of fifteen sen

[wall towards the door. draw near to the door. 1 draw nearer

fo the door. I get to the doot. I stop a the door.

| stretch out my arm. I ake hold of the handle, 1 tuen the

hhandle, open the door. 1 pull the door

ume 2A -Mahoccat Hoy ofLangugeeoching 21

“The door moves, The door turns on its hinges. The door turns

and turns, Lopen the door wide. Tet go ofthe handle,

The itcen eee ve an uncovetonly ge nue fanaa

ropentes tout tens word orca complex. Ths no Simple Ye

aerate Govin wr nace wih Sach sons beaut the naa

tus wey understood, store, rece and rite To real Yee Wasa man

Satna ead this nad hi ss were arg ost nthe sue of

tests poplar Direct Method. Buta we lok hack now ener more than ae

wir of ngugevesctng or, we con appreciate the ngs of ts os

os ange teacher

‘THE DIRECT METHOD

the “naturalistie"—simulating the “natal” way in which children fearn fest tan

uges—approaches of Gouin and a few of his contemporaries did not take hold

immediately A generation ater applied linguistics finally established the credit

‘such approaches, ‘Thus ie wa that a the tara ofthe century.the Direct Method.

became dite widely known and peacticed

The basic premise of the Direct Method was sini

‘ethos, namely that second language learning should be more ike first language

Jearning-—lots of ora interaction, spontaneous use of the language, no translation

between fist and second languages and litle or no analysis of grammatial rules

Richards and Rodgers (1986-9-10) summarized the principles ofthe Direct Methox!

to that of Gouin Series

1. Classroom instruction was conducted exclusively in the target language

2. Only everyday vocabulary and sentences were taught

5. Oral communication skills were buile wp in a carefully graded progression

‘organized around question-and-answer exchanges between teachers and st

‘dents in smal intensive classes.

4. Grammar was aught inductively:

5. New teaching points were taught through modeling and practice.

6 Concrete vocabulary was taught through demonstration, objects, and pictues

aibsract vocabulary Was taught by association of ideas,

+. Both speech and listening comprehension were taught

8. Correct pronunciation and grammar were emphasized,

“The Direct Method enjoyed considerable popularity a the beginning of the

twentieth century It was most widely accepted in private language schools where

Nudents were highly motivated and where nativespeaking teachers could be

Cmployed One of the hest known of is populaizers was Charles Betta (who

tnever use the term Disect Method and chose instead to call his method the Berlitz

22 cum? Arve

cia istry a ange Teaching

Method). To this day “Berl” is a household wor; Berlitz language schools are

thriving in every countey of the wold,

But almost any “method” can succeed when clients are willing to pay high

prices for small classes, individual attention, and intensive study; The Direct Method

Aid not take well i public education, where the constraints of budget, lasroor

size, time, and teacher background made such 4 method dificult to use, Moreover,

the Direct Method was criticized for its weak theoretical foundations. Is success

may have been more a factor of the skill nd personality of the teacher than of the

thodology ise

By the end of the frst quarter of the twentieth century, the use of the Direct

Method had declined both in Furope and in the US. Most language curriculs

secured tothe Grammar Translation Methox! orto a“eading approach that emph

Sized reading skills in foreign languages. Buti is interesting that by the mille of

the twentieth century. the Direct Method was reived and redirected into what Was,

probably the most vise ofall Language teaching “revolutions” inthe miolern er,

the Audiolingual Method (see below). So even this somewhat shortiived movement

language teaching would reappear in the changing winds and shifing sands of

ory

‘THE AUDIOLINGUAL METHOD

{mn the frst half ofthe twentieth century, the Direct Method did not take hold in the

US the way it din Europe. While one could easly find nativespeaking teachers

fof modern foreign languages in Eugope, such was not the case in the US, Also,

Furopean high school and university stadents did not have to travel far to find

‘opportunities to put the orl skills of another language to actual, practical use

Moreover, US educational insiutions had hecome firmly convinced that a reading

approach to foreign languages Was more useful than an oral approach, given the

perceived linguistic isolation of the US atthe time. The highly influential Coteman

Report (Coleman 1929) hal persuaded foreign language teachers that it was imprac

\ica 10 teach oral skills and that reading should become the focus. ‘Thus schools

returned in the 1930s and 1910s t0 Grammar Translation, “the handmalden of

reading” owen, Madseu, & Hier 1985),

“Then World War It beoke out, and suldenly the US was thrust into a workdwide

‘conflict hejghtening the need for Americans to become orally proficient in the la-

fuiges of both their allies and their enemies. The time was ripe for Language

teaching revolution, The US military. provided the Impetus with funding. for

special, intensive language courses that focused on aur/ora skills: these courses

ame to be known as the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) of, mare coll

‘quilly the“Aemy Method” Characteristic of these courses was a great deal of ora

Aactvity—pronunciation and patter drills and conversation practice—with vitally

hone of the grammar and translation found in triditiomal classes, Wi ionic that

Cures 2A Mecca” Hit of ange ecting 23

humerous foundation stones of the dscanded Direct Method! were borrowed and

injected into this new approach, Soon, the success of the Army Method and the

revived national imerest in foreign languages spurred educational institutions to

dope the new methodology. In all ts variations and adaptations, the Army Method

‘came fo be known inthe 1950s 2s the Audiotingual Method

Methox! (ALMD ws fray grounded in linguistic and psycho-

logical theory, Structural linguists of the 1940s and 1950s were engaged in what

they claimed was a "scientific descriptive analysis" of various languages: teaching

tmethodologiss saw a direct application of such analysis vo teaching linguistic pat

terns Fries 1945). At the same time, behaviorstic psychologists (PLIT, Chapter 4)

“advocated conditioning and habitformation models of learning that were perfectly

married with the mimicry dais and pattera practices of audilingual methodology.

"The charicteritics of the ALM may be summed up in the following Ist

(adapted from Prator & Celee Mureia 1979)

1. New material is presented in dialogue form.

2. There is dependence on mimicry, memorization of set phrases, and over

tearing.

Structures are sequenced by means of contrastive analysis and taught ome at a

4. Strctural patterns are taught using repetitive dil

5. There is litle of no grammatical explanation. Grammar i taught by inductive

analogy rather than by deductive explanation

6, Nocabutary is stecty limited and feared in context.

7. There is much use of tapes language labs, and visual ak

{8 Great importance is attached to pronunciation.

9, Very lite use of the mother tongue by teachers is permitted

10, Successful responses are immesdately reinforced.

11, Thee is a great elfort to et students to produce erroesiee utterances,

12, Thee isa tendency to manipulate language and disregard content

For a number of reasons the ALM enjoyed many years of popularity and even

to this day, adaptations ofthe ALM are found ip contemporary methaxdologies. The

‘ALM was fitmly rooted in respectable theoretical perspectives of the time

Materials were carefully prepared, tested, and disseminated to educational insti

tions. “Success” could be overtly experienced by students as they practiced

tlalogues in ofthours, Hut the popularity was not to lst forever. Challenged by

‘Wiles Rivers’s (1968) eloquent criticism of the misconceptions of the ALM and by

{ts ultimate failure 10 teach longterm communicative proficiency, ALM popularity

‘waned. We discovered tha language wis not really acquired through a process of

habit formation and overlearning, that ertors were not necessarily co De avovded at

all cost. and that structural linguists did not tll us everything about language that

Ive needed to know, While the ALM was yllant attempt to reap the fruits of lane

tsuage teaching methodologies that had preceded iti the enk! it stil fell short as all

24 ows? AM! Hy of ange Thing

methods do, But we learned something from the very falure of the ALM to do

‘everyting it had promised, and we moved forward

COGNITIVE CODE LEARNING

‘The age of auiolinguatim, with ts emphasis on surface forms and on the rote prac

tice of scientifically produced patterns, begin to wane when the Chomakyan tev

lution in tinguistcs cured linguists and language teachers toward the “deep

Structure“ of language. Increasing interest in generative tanstormationalsrammat

and focused attention on the rule governed nature of language and lane

sition Jed some languageseaching programs to promote a deductive approach

father than the inductivty of the ALM. Arguing that chikiren subeconsetouny

acquire a system of rules, proponents ofa cognitive code learning methxloloxy

(ce Carroll 1966) began to inject more deductive rule learning into language

classes. fn an amalgamation of Audiolingval and Grammar Translation technles,

«lasses retained the dling typical of ALM but added healthy doses of rule explane

‘ons and reliance on grammatical sequencing of materia,

Cognitive code learning was not so mich a method as it was an approach that

‘emphasized a conscious awareness of rules and their applications ta sere! an

uage learning, Ie was a reaction tothe strictly behavoristic practices of te ALM,

and ironically retuen to some ofthe practices of GrammarTranslation, As teachers

and! materials developers saw that incessant

nti of potently rote mater

‘so creating communities poficent kemerra ne twist es heeded ed

conve coe earning appeared to prove fast such tw, Unortnutey the

vation was shorived fora rly ar re ding bored tadeate wert co

tveattemon tothe rues, paradigms intricacies and excep oft ngage see

taxed the mental reserves of language students. : mate

The profesion needed some spce nd verve and innovative nds in the sp

ite 19708 were wp tothe challenge

“DESIGNER” METHODS OF THE SPIRITED 1970S

‘The decade of the 1970s was historically significant on two counts. Fist, perhaps

‘more than in other decade in “modern” langwage-tcaching history, resetnch on

second language learning and teaching grew from an offshoot of Hinsustis to 4 die

Spline in its owa right. As more and more scholars specialized their efforts in

second language acquisition studies, our knowledge how people lear

ope lea languages

Inside and outside the classroom mushroomed. Second, inthis spirited atmosphere

‘of pioneering research, a number of innovative if not revolutionary mcthox were

‘conceived. These “designer” methods (to borrow a term from Nunn 989% 9°)

‘were soon marketed by entrepreneurs asthe latest and greatest applications of the

‘utiisciplinary research findings of the day

(

umm? A Mecca Hit of angge Feaching 25

‘Taday, a8 we took hack at these methods, we can applaud them for their inno

‘ative Mas, for thee attempt to rouse the kanguageeaching, Woekd QUE ofits aio

Tingust sleep, and for their stimulation of even more research as we sought 10

dliscover wh they were not the godsend tha their inventors and marketers hoped

they would he. The scrutiny thatthe designer methods underwent has enabied 0s

today 10 incorporate certain elements thereof in our current communicative

approaches to language teaching, Let’ look at five ofthese products of the spirited

1970,

1, Community Language Learning

By the decade ofthe 1970s, as We increasingly recognized the importance of

the affective domain, some innovative methods took ona distinctly affective nature

Community Language Learning is a classic example of an afectively based

method,

In what he called the “Counseling-Learning” model of education, Charles

‘Curran (1972) was inspired by Carl Rogerss view of education (PLIT, Chapter #) 48,

‘which Teamers in a classroom were regarded not as a "class" but as a “group"—a

[group in nced of certain therapy and counseling. The social dymamics of sch 3

|90up were of primary importance, In onder for any learning to take place, group

members frst nceded to interact an inteepersonal relationship ia whieh students

tind teacher joined together to facilitate learning in & context of valuing exch inde

‘dual inthe group. In such a surrounding, each person lowered the defenses that

prevent open interpersonal communication. The anxiety caused by the edues

tional context was lessened by means of the supportive community. The teachers

presente was not perceived 382 threat, nor was ie the teachers purpose to impose

limits and boundaries, but eather, as a true counselor, center his oF ber atteaton

fon the clients he students) and their needs, “Defensive” learning was made unnee:

essary by the empathetic relationship between teacher and students. Cuerans

CCounseling-Learning model of education thus capitalized on the primacy of the

needs ofthe learners—clients—who gathered together in the educational comm

rity to be counseled.

‘Curran’s Counseling-Learning model of education was extended to language

Fearing contexts in the form of Community Language Learning (CLL). While pr

"cular adaptations of CLL were numerous, the hasie methodology was explicit The

s10up of elients (for insance, bewinning learners of English), having est established

Jn their native language (ay, Japanese) an interpersonal relationship and trast were

seated ina circle withthe counselor (eachet) on the outside of the eicle. When

‘one of the clients wished to say something to the group or to an individual, he oF

she Said it inthe native language Gapanese) and the counselor tansated the uter

ance buck to the learner ia the second language (English). The learner thea

repeated that English sentence as accurately as possible, Another client respond

in Japanese: the uterance 9s translated by the counselor into English the client

repeated itjand the conversation continued. If possible the conversation wis taped

26

for lite stein. and atthe end of each session, the earners inductively attempted

togethce to glean information about the new language. If desirable, the counselor

might take a more directive role and provide some explanation of certain linguistic

rues oF items

The first stage of intense strugele and confusion might continue for many sey

sions, but always with the support of the counselor and of the fellow clients

Gradually the learner became able to speak a word or phase directly in the foreign

fangwage, without translation, ‘This was the est sign ofthe learner's moving away

from complete dependence on the counselor. As the learners gained more and

mone familiarity with the foreiga language, more and more direct communication

‘Could take place, with the counselor providing less and less direct translation and

Information. After many sessions, perhaps many months or years ater, the learner

achieved fluency in the spoken language. The learner bad at that point become

ndependent.

‘CLL reflected not only the principles of Carl Rogers's view of education, but

aso basie principles of the dynamics of counseing in which the counselor, through

‘careful attention to the client's needs, aids the cient i moving from dependence

and helplessness 1 independence and selFassurance

“There were advantages and disadvantages 10a method like CLL "The affective

audvantages were evident. ELL wae an attempt a pat Rogers philosophy kato

tetion and to overcome some ofthe threatening affective factors in second Language

Teaming. The threat of the atknowing teacher of making blunders ia the foreign

language infront of classmates, of competing against peers—al threats that can lead

to 2 feeling of alienation and inadequacy—were presumably removed. The coun

‘Selo allowed the learner to determine the type of conversion and to analyze the

foreign language inductive: In situations in which explanation or translation

scemed to be impossible it Was often the clentearner who stepped in and became

1 counselor to aid the motivation and capitalize on intrinsic motivation

There were some practical and theoretical problems with CLI. The counselor

teacher cou! Become too nondlirective, The student often needed direction. espe

Cally in the frst stage, in which there was such seeming’ endless struggle within

the foreign language. Supportive but assertive direction from the counselor could

strengthen the method. Another problem with CLL was ts reliance on an inductive

Strategy of learning, 1is well aecepted that deductive learning i both a viable and

Clicient strategy of learning and that adults pariculaely can benefit from deduction.

4s well as induction. While some intense inductive struggle is a necessary Comper

rent of second language fearing, the inital grueling days and weeks of floundering

in ignorance in CLL, coukd be alleviated by miore directed, deductive fearing, “by

being told Perhaps only in dhe second or tind stage, when the learner has moved

to more independence, sn inductive strategy really successful. Finally.the success

‘of CLL depended largely on the transition expertise of the counselor, Translation

{s an inttate and complex process that is offen “easier sud than done”: if subtle

aspects of langue are mistranslated, these can be a less than effective under

Cuter A “Mecca” Hany of ange acting 27

standing ofthe target language

“Tokay virtaly no ne wses CLL exclusively ina curticulum. Like other methods

in this chapter, it was far too restrictive for institutional ngage programs

However, the principles of discovery learing, stulentcentered participation, and

development Of student autonomy Gdependence) all remain viable in their app

‘ation to language classrooms, sf the case with virally any method the theoret

{eal underpinnings of CLL may he creavely adapted to your own situation

2. Suggestopedia

‘Other new methods of the decade were not quite a strictly affective as CLL

‘Suggestopedia, for example, was a method that was derived from Bulgarian psy

chologist Georgi Lozanov's (1979) coatention thatthe human brain could process

treat quantities of material if given the right conditions for learning, among, which

fe a sate of relaxation and giving over of eonteol to the teacher. According to

Loranox, people are capable of eaening much more than they give themselves

credit for. Drawing on insights from Soviet psychological research oa extrasensory

[perception and from yoga, Lozanov created a method for learning that capitalized

‘on relaxed states of mind for maximum retention of material. Music was central (0

his method. Baroque music created the kind of*relaxed concentration” that led to

sunerieaming” (Ostrander & Schroeder 1979: 65). According to Lozano, during

the soft plying of haroque musi, one can take in tremendous quantities Of mate

ial de to an increase in alpha brain waves and a decrease in blood pressure and

prlse rate.

In applications of Suggestopedia to foreign language learning, Lozanov and his

followers experimented with the presentation of vocabulary, readings, dialogs ole-

plays drama, and a variety of other typical classroom activities. Some of the class

room methodology wis not particulitly unique. The primary diflerence lay in a

gnificant proportion of activity carried out in soft, comfortable seats in relaxed

Sates of consciousness. Students were encouraged to he a8" childike” as possible

yickling all authority to the teacher and sometimes assuming the roles (and names)

‘Of mative speakers of the foreign language. Students thus hecame “suggestible”

Lozano (1979: 2°2) described the concert session portion of Suggestopedia ln

uae class:

At the beginning ofthe session all conversation stops fora minute oF

"oan the teacher listens to the music coming froma tperecorder.

He waits and listens €0 several passages in order to enter into the

mood of the music and then begins to read or recite the new text his

voice modulated in harmony’ with the musical phrases. The students

follow the text in their textbooks where each lesson is trnsated imo

the mother tongue, Between the frst and second part ofthe concert,

there are several minutes of solemn silence. In some cases, even

longer pauses can he given to permit the students to stir a lite

6

Before the beginning of the second part of the concert, there are

again several minutes of silence and some phases ofthe music are

heard again before the teacher begins to read the text. Now the st

dents close their textbooks and listen to the teacher's reading. A th

end, the students silently leave the room, They are not told to do an

homework on the lesson they hive jst hal except for reading it cur

sorily once before going to hed and again before getting up in the

morning

Suggestopedta was enitcized on a number of fronts. Scovel (1979) showed

‘quite eloquently that Lozanov's experimental dita in which he reported astounding,

Fesults with Suggestopedta, were highly questionable. Moreover the practicality af

Using Suaaestopedia isan issue that teachers must face where music an confor:

able chairs are not available. More serious i the issue of the place of memorization

fn language learning. Scovel (1979. 260-61) noted that lozanows“Innumerable

‘erences 10... memorization ...0 the tol exclusion of referenecs to "understanding

and/or ‘creative solutions of problems convinces this reviewer atleast that sis

Eestopedy...is am attempt to teach memorization techniques nd is not devoted 10

the far more comprehensive enterprise of language acquisition "On the other hand,

‘other researchers, including Schiffer (1992: sv), have sugested a more moderate

Position on Suggestopedia, hoping “to prevent the exaggerated expectations of

Suggestopedia that have been promoted in some publications

Like some other designer methods (CLL and the Silent Way, for example

Suggestopedta became a business emtespris ofits own, and it made promises in the

advertising world that were not completely supported by research Despite such

“dubious claims Suggestopedi gave the languageteaching profession some insight,

We learned a bit about how to believe in the power ofthe buntan brain. We learned

that deliberitely induced states of relaxation may’ be beneficial in the classroom

‘And numerous teachers have at times experimented with various forms of music #6

A wa to get students to sit back andl relax

3. The Silent Way

Like Suggestopedia, the Silent Way rested on more cognitive than affective

anguments for is theoretical sustenance. While Calch Gatteyno its founder, Was

Sai to be interested in “humanistic” approach (Chamot & McKeon 1984-2) 10 eh

‘ation, ach of the Silent Way was charieterized by a problem-solving approach to

learning. Richards and Rodgers (1986: 99) summarized the theory of learning

Jnchind the Stent Way

4, Learning i factated ifthe learner discovers of ereates rather than remem

bers and repeats what isto be learned

2. Learning is faciitated by accompanying (mediating) physical objects,

3. Learning is faciitated by problem solving involving the material to be learned

ie? “Moca Hi of angge ching 29

Discovery leaning." popular educational tend ofthe 1960s, advocated less

learning “by being told” and more lexning by discovering for oneselt various facts

nd principles. tn this way, students constructed conceptual hierarchies of their

‘own that were a producto the time they invested, Ausubel subsumption” (PLLT,

‘Chapter 4) was enhanced by discovery learning since the cognitive categories were

Created meaningfully with less chance of rote learning taking place. Inductive

processes were also encouraged more in discoverylearning metho

The Silent Way capitalized on such discovery-exening procedures. Gattegne

(1972) believed that learners should develop independence, autonomy, and respon

‘ibilig:_At the same time, learners ina Silent Way classroom hid to cooperate with

‘each other in the process of solving language problems. The teacher—a stimulator

but nota handholder—was silent mich ofthe time, thus the name ofthe metho

‘Teachers had to resist their instinct to spell everything out in black and white, to

‘come tothe ad of scents a the slightest downlal: they had "get out ofthe wy”

“while students worked out solutions,

In a language classroom, the silent Way typically iized as materials a set of

‘Cuisensire rods—small colored rods of varying lengths—and a series of colorful,

‘wall charts. The rods were wsed to introduce vocabulary (colors, numbers, adjec:

tives Hong, ort and 20 onl), wet ite, take, pick tp, drop), and yn nse

‘comparatives pluralization, word order, and the lke). The teacher proved single-

‘word stimuli or short phrases and sentences, once of twice and then the stents

refined their understanding and pronunciation among thenseves with minimal cor

rectve feedback from the teacher. The charts introduced pronunciation modes,

‘grammatical paradigms, and the tke

Like Sugestopedia. the Silent Way has had its share of eitcism, In one sense

the Silent Way was too harsh a method and the teacher too distant to encounige &

‘communicative atmosphere. Students often need more guidance and overt correc.

tion than the Silent Way permitted. There ate numberof aspects of language that

can indeed he "told to students to theie beni they need not as in CLL as well,

strugsle for hours oF days with a concept that could be easly clarified bythe

teacher's direct guidance, The rods and charts wear thin after a few lessons, and

other materials must be introduced, at which point the Silent Way classroom can

Took ike anyother fanguage classroom

[And yet, the underying principles of the Silent Way are valid, All 10 often

wei tempted as teachers to provide everything for our sents, neatly served up

fon a silver platter We could henefit from injecting healthy: doses of discovery

ming into our classroom activities and from provieing less teacher talk than we

vswally do to let the students work things out om their own,

‘Total Physical Response

James Asher (1977), the developer of Fotal Physical Response (TPR), actually

bneqan experimenting with TPR inthe 1960s, but it wis almost a decade before the

20

method was widely discussed in profesional circles. "Tolay TPR. with simplicity as

‘ts most appealing fice, a household word among language teachers

‘You will ecall from earlier inthis chapter that more than a century ago, Gouin

signed his Series Method on the premise that language associated with a series of

Simple actions will be easily retained by learners. Much later, psyehologisis deve

‘oped the “trace theory” of learning in which it was claimed that memory is

Increased if is simlated, or “raced” theough association with motor activity

‘Over the years, language teachers have intuitively recognized the value of assoc

ating language with physical acuviy. So while the idea of bulding a method of la

"age teaching on the principle of psychomotor associations was not new, it was

this very ea that Asher capitalized upon in developing TPR.

‘TPR combined a number of other insights in ts rationale. Principles of child

Janae acquisition were important. Asher (1977) noted that children, in learning,

theie first language, appear to do alot of listening before they speak, and that thee

listening is accompanied by: physical responses (reaching, grabbing. moving

looking, and so forth). He also fave some attention to right-brain learning (PLT.

Chapter 5). According 10 Asher motor activity isa righcbrain function that should

precede leftbeain language processing. Asher was also convinced that language

Classes were offen the locus Of too much anxiety, so he wished to devise a method

that was a6 sitewfiee as possible. where learners would aot feel overly sel

conscious and defensive. The TPR classroom, then, was one in which students did

2 great deal of listening and acting. ‘The teacher was very directive in orchestrating

‘performance: “The instructor isthe director ofa stage play in which the students

ae the actors" Asher 197743).

‘Typically, TPR heavily uulzed the imperative mood, even into more advanced

proficiency levels, Commands were an easy way to get learners to move about and,

to loosen up: Open the window, Close the door, Stand up, Sit down, Pick up the

ook Give it 10 Jobn.and so on. No verbal respoase was necessary. More complex

syntax could be incorporated into the imperative: Draw a rectangle on the ebalk-

Doard, Walle quickly to tbe door and bit i, Yumor is easy 40 introdce: Walk

slowly to the window and jump, Put your tootbbrusb in your book (Asher 1977:

55), Interrogatives were also easily dealt with: Where is the book? Who és Jobn?

(tucents pointed tothe book or to John). Eventually students, one by one, would

{ec comfortable enough 10 venture verbal responses to questions then to ask ques

tions themselves, and to continue the process

Like every other method we have encountered, TPR had its limitations.

seemed to be especially effectve inthe beginning levels of language proficiency but

It lost its eistinctiveness as learners advanced in their competence. In aTPR class

room.after students overcame the fear of speaking out, classroom conversations and

‘other activites proceeded 2s in almost any other communicative language clas:

room. In TPR reading and writing activities, students are limited «© spinning off

from the oral workin the classroom. Ii appeal to the dramatic or theatrical nature

‘of angvage learning was attractive, (See Smith 198 and Sten 198% for discussions

Cauren2 A Meth” Hay of ange Teching 31

fof the use of deama in foreign language classrooms.) But soon learners! needs for

Spontaneity and unrehearsed language must be met

5. The Natural Approach

Stephen Krashen's (1982, 1997) theories of second language acquisition have

bocen widely discussed! and hotly debated over the years (PLLT, Chapter 10). The

iijor methodological ofshoot of Krashen's views was manifested in the Natural

Approach, developed by one of Krishen's colleagies, Trey Terrell (Krashen &

Terrell 1983). Acting on many ofthe claims that Asher made fora comprehension:

based approach such a6 TPR, Krashen and Tertell felt that learners would benesit

from deliying prodiction until speech “emerges: that earners should be 2s relaxed.

as posible in the classroom, and that great deal of communication and"acquisition”

should take place, 38 opposed to analysis. In ft, the Natural Approach advocated

the use of TPR activities atthe beginning level of language learning when “compre:

hhensible inputs essential for triggering the acquisition of language

‘There are a number of possible long-ange goals of language instruction. 9

some cases second languages are learned for oral communication: in other cases for

‘writen communication; and! in still ethers there may be an academic emphasis on,

say; listening to lecues, speaking in a classroom context, or writing a research

paper. The Natura Approach was aimed atthe goal of basic personal communica

‘on skills that i, everyday language stuations—-conversations, shopping, listening

to the radio, and the like. The initial task of the teacher was to provide compre

hhensibe input thats, spoken language that is understandable tothe learner or just

a lite heyond the lesmer’s level. Learners need not sty anything during this"slent

Period” unl they fel ready to do so, ‘The teacher was the soutce ofthe learners

Input and the ereator of an snteresting and stimulating varity of elasroom activ

ties—commands, games, skits, and small-group work

In the Natura Approach, learners presumably move through what Krashen and

Terrell defined as three stages(a) The preproduction stage ts the development of is

tening comprehension skils. (b) The early production stage is usualy marked! with

crrors as the student struggles withthe language. The teacher focuses on meaning.

here, not on form and therefore the teacher does not make a point of correcting

‘errors daring this stage Canless they are gross erzors that block or hinder meaning,

entirely), (6) The last stage ks one of extending production into longer stetches of

‘discourse involving more complex games, role-plays, open-ended dialogues, discus

sons, and extended small group work. Since the objecuve im this tage is to pro

mote fluency: teachers ae asked to be very sparse in tk

“The most controversial aspects ofthe Natural Approach were ts advocacy of &

“silent period (delayof oral production) and its heavy emphasis on comprehensible

input. The dey of oral production until speech "emerges" has shortcomings (see

Gibbons 1985). What about the student whose speech never emerges? And with

al students at different timetables for this socalled emergence, how does the

Teacher manage a classroom efficiently? Furthermore, the concept of comprehen

sible input i dificult eo pin down, as Langi (198-18) noted:

32 cower? Autocity of Langage Kachin

nv does one know which structures the lrners are to be provided

with? From the examples of “teacher talk” provided in the book

(Krushen and Terrell, 1983), communication interactions seem to he

-uided by the topic of conversation rather than by the structures of

the language. The decision of which strictures to use appears to he

Jeft to some mysterious sort of intuition, which many teachers may

snot possess

(On a more positive note, most teachers and researchers agree that we ae all

{oo prone to insist that learners speak fight aay, and so. we can take from the

Natural Approach the goox! advice that fora period of tine, while students row

accustomed to the new language their silence is beneficial, Though TPR and other

forms of input, students language egos are not as easily threatened, and they aren't

forced into immediate rsktaking that could embarrass them. The resulting sit

confidence eventually can spur a student to venture to speak out.

Innovative methods such as these five merous ofthe 1970s expose us to prin

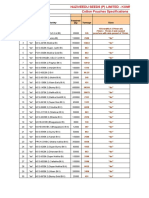

Table 2.1. Approaches and methods—an overview (adapted from Nunan 1983)

Tory of lng

Tapginges aspen

teegevemed ces

CORR cnet

ating |

“eon fearing Ohta Saher

Taba trnaons le Condo tacts ol Grote abo

‘telooidmeelc- Sam orm st peegy mono,

operetta: Ce

‘wie any moe ean ashe

Sih nese.

"aaa pes

Balas

‘ite

sewn

eth Freier me

‘ols onto

Tate

Fina pesca

ot Pica

ach ange con

Povo ta

Spat roc

Sieur ae ye

al ge

The Sent Wy

pone cs.

The Natura Apprach Languapeaning

he eee ange

‘er

ieulole mowing

TERS een chaniocicing @ Saonctncs

1 Kang cree podce mer sah amma rv

Sone poductonsLan omnis ei eel cg

Simp rah ced re gym, a con

‘iiqeve carmen” hie years ing te

(een ctoing

Proceso aming Neste fn cor Bakaly sca

‘Sco anguage eet mance eso pared urd

‘menage fom ptt ined of gama sd

iiEomne Leman” he gammarct ie 2) ea sry es

‘Sanimecol cog terrae how octal aond

‘Repuces Sirmarie ins anpage. othe ganmatcl

‘hoon ol are pie

ge ee tore

Leaning ivohes he Ro speci ajectins_ No wt yin, Cone

‘os poton ive Reweae maeeyis popes tgs

iron ite er go thetopies Saban

independence ‘ntnton andthe

‘Scher lomultons

Theva wo mayselL2 Deseo ge gle ned on skaton of

Ibnginge Slope ty Sngvacedsit” imate aes

estion” nantes tune comes sal ded om

Stbtinscas prone ese il Fur id ae ee

nian com. Sa ane pron

‘Sonetedn aq alien sade

on mage

Shae in eee eer

“used to induce this state goes ts of wocabary ie

ecaeet

Tapa da wok

‘wal sco

‘Sars gear,

indvalAc-

is ecg a sae

rig yeh

Combinatn of eo

fveand conan

‘Tania ap er,

cvs sawing om

ior

stove ye

‘eng veces Une

Sept,

era aren

‘son args mt

Seep mitpendene,

‘Stand 2 eer

i

commen origi

ots a

Seton

sd eter

exllntny arn

ing da

the cn |

(rh ance,

ae and dete

acer us a ac

Seen

Fete

vk re i,

Seer ate

Course

mand som

eet npt nt

‘Set Sarasa

Soe aml arin

Stes me

atten on

‘ins bane one ne

‘td conden

arian mae

Salman

otal wie, etn, and

rs so

‘ef ie orc

fronton ad =

cy

Seren, wich

‘ud is pe

Nitti Sloped

Steve pee

{neonenemesten

‘Son

non foes ne

‘city quay and

egress a

a

nage eehing | —Sopgetpeda

‘Actes evching al bjs wll de Wil aca sono ol

Smeal! a wl tered” ces men

thing one ich lear ng ees ek:Oring

iting ene Se wie sy he

eg arin cm

cn

‘eae a gn

‘Sr sta

ee

ns re

Tea ana crue

proves mage

Thay le rong

‘mance angenpe

5

26

Sa alsa Ea ae ee a Se |

‘oun 2A Mata” Hist of ange Techn

Vide a link between a dynasty of methods that were pershing and a new era of an

‘Ruage teaching that isthe subject ofthe next chapter

As an aid to your recollection of the characteristics of some of the methods

reviewed easier ou may wish to refer to Table 2.1 (pp, 34-35), ia which the

-Audiotingual Method, the Sve"designer” methous and the Communicative Language

Teaching Approach are summarized according to eight diferent criteria,

‘On looking hack over this meandering history, you can no doubt see the cycles

of changing winds and shifting sands alluded to ear. In some ways the cycles

Were, as Marckwardt proposed, each about a quarter of a century in length, oF

roughly a generaion, In this remarkable succession of changes, we leaned soe

‘thing in eich generation, We did not allow history simply to deposit new dunes

{exactly where the old ones fay. So our cumulative history has taught us to appre

ate the value of “doing” language interactives of the emotional (as well as eogni

tive) side of learning, of absorbing language automaticaly of Conseionsly analying

‘and of pointing leaners towand the real workd where they will uc English con

rmunicatively

In the next chapter we look at how we reaped those benefits to form an inte-

rated, unified, communicative approach to language teaching tha is no longer bi

acterized by a series of methods

‘TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION, ACTION, AND RESEARCH

Note: CD Individual work; (G) group oF pair work: (C) wholeclass discussion }

4. @ Since this chapter refers to some baste principles and issues that are nor

‘mally covered in a course in second language acquisition (and in books like

PLET and Mitchell and Myles 1998), itis quite important at this point for you

{review such material, For example, vatied theories of learning are implied

all the methods just reviewed; the role of affective factors in second ta

_Rwige acquisition is highlighted im some methods, conseious and subseon

scious (or focal and peripheral) processing assumes various roles, depending,

‘on the metiod in question. Ifyou encountered concepts or issues that you

needed 0 brush up on as you read this chapter, make somte time for a thoe

‘ough review

2. (G) Giveo the choice of Richards and Rodgers's or Anthony's earlier model of

looking atthe concepts of approach, methou, design, procedure, and tech

hique, which is preferable? Direct sal soups to discuss preferences. if

there is disagreement, groups should try to come to a consensus. Make sure

soups deal with Richards and Rodgers rationale for the change

‘3 (G) Consider the Series Method, the Direct Method, and the Auioing

Method. Assign a diferent method to each of several small groups. The task

{to list the theoretical foundations on which the methexl rested and share

findings with the whole class,

(

|

|

CUTE 2A Metin of ange eching 37

4. © Richards and Rogers 19865) aid Grammar Transat “sa method for

tvhich there is nother this fo harsh a jamin As stents i they

Barce withthe theorsesnest of Granta Trasation and why

5. (GIO Reviow the five"desgner” methods. I chs site permis asin a

seta to each of ve diferent smal groups were cach grou wl defen

its method sysins the others. "The grup tak so prepare argument in

fier of ts method question to ask of her method and counter arguments

inst what other ups might a them. Altera modified debate, cid with

2 wholeclas discusion

6. (OTe ofthe fie “signer” methods (CLL, Sen Ws; and Suagestopes)

Senta sme een props, noma

publishing and educational company. Ask stent consider how tht fact

Init color she objectivity with wich ts backers promote each method

{nd (b) pie reception to

7. © Caper 1 described casrvom lesson in Engh a a ccond ange

‘sk stents ook hack tho tat lemon nai at of dhe aos

‘methodological postons that have occpied the last cer or of tn

ge teaching to determin how he activis/ecnigus in the lesson

Fefcc some ofthe theoretical foundations on which certain metho were

‘cnsracted Fr example, whem the teacor da ek chal del 6,

Flow would one support tat technique wih principles that ay bein the

ALP

8. GG/C Ask students in sal groups to reiew the cycles of siting sand

Since Gouin’ tine. How di cach new metho borrow fom previous prac

teea?‘What cil each reject in previous practices) Each group wil then share

their conclasions with thereat ofthe class, On the Bod, ou might econ

strict the istrial pogression inthe form tne line wi characteris

iste french erate permits try to determine wa the prevaling ate

tects or pole mood wis when certain methods were flowering. For

tame: the AIM was» product af amity taining program an flourished

drng an en when scent soltos oa problems were diligently sought

Are there some logcl connections here?

FOR YOUR FURTHER READING

Anthony, Edward. 1963. “Approach, method and technique” Englisy Language

Teaching 17° 63-67

hs this seminal article, Antbony defines and gives examples ofthe throe bile

terms. Methods are seen, perbaps for the fst time, as guided by ard built

pon solid thooretical foundations. His definitions have prevailed fo is

day sn syformal pedaggical terminology

8

[Richards Jack and Rodgers, Theodore. 1982. "Method: Approach, design, proce:

dure? TESOL Quarterly 16: 153-66,

‘The authors redefine Antbony’s orginal conception of the terms by viewing

“metbod as ans mbrlla term covering approach, design, and procedure

Full explanations of the terms are offered and examples provided. This

article also appears asa chapter tn Richards and Rodgers (1986),

Richards, Jack and Rodgers, Theodore. 1986. Approaches «and Mebods én

Language Teaching. Cambeidge: Cambridge University Press

‘his book presents a very useful cxeniew of @ number of different metbods

teithin the rubric of approaches that support them, course designs thal ti

them, and classroom procedures ecbnigues) that manifest them,

‘ardovitarlig, Kathleen, 1997. “The place of second language acquistion theory

in language teacher preparation” In BardovsHarlg, Kathleen and. Hartford

Bevery: 1997. Beyond Methods: Components of Second Language Teacher

Haducation, New York: McGraw-Hill. Pages 18-41

Because an understanding of language-teaching history abo implies the

tmporsance ofthe place of second langage acquisition research, this phece

afr i rdsfrom rocarch pth pag cra te

—____CHAPTER 3

THE PRESENT: uals

AN_INFORMED “APPROACH” ___

‘The ‘methoxtical” history of the previous chapter, even with our brief look at

Notional Functional Sylabuses, does not quite ring us up to the present. By the

tend ofthe 1980s, the profession had learned some profound lessons from ot past

‘eanderings. We had learned to be cautiously eclectic in making enlightened

choices of teaching practices that were solidly grounded in the best of what we

Knew about second language learning and teaching. We had amassed enough

reseurch on fearing and teaching that we could jadeed formulate an integrated

approach to lnguage teaching practices. And, peshps ironealy the methous that

‘were such strong signposts of our century-old journey were no longer of great com

sequence in marking our progress. How di that happen?

In the 1970s and early 1980s, there was a good deal of hoopla about the

“designer” methods described in the previous chapter. Even though they weren't

widely adopted as standard methods, they were nevertheless symbolic ofa profes

sm at Feast partially caught up in a mad scramble to snveat a new method when

the very concept of “method was eroding under our feet. We didn't need a new

‘method, We needed, instead, to get on with the business of unifying our approach

10 Language teaching and of designing effective tasks and techniques that were

informed by that approach,

And so, today those clearly lentifable and enterprising methoxls are an ier

‘sting if not insightful contribution to our professional repertoire, but few pct.

toners look to any one of them, or their predecessors fo a final answer on How to

{each a foreign language (Kunaravadiveld 1994, 1995), Method, asa untied, cobe.

sive finite set of design features is now given only minor attention” ‘The profession

has at last reached the point of maturity where we recognize thatthe diversity of

“While we may have outgrown our need Yo search for such definable methods

nevertheless the term "methodology" continues to be used, af wolld In any other

Delaviorl scence, o refer tothe sstematc application of validated principles to

practical contexts. You need not therefore subscribe toa particular Method (

api M) in onter to engage in a°methodology”

a9

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Comprehensive English Grammar. CH 1Document3 pagesComprehensive English Grammar. CH 1Cote CabreraNo ratings yet

- 04 Listening Korean For Beginners PDFDocument14 pages04 Listening Korean For Beginners PDFCote Cabrera100% (1)

- Korean Phrase BookDocument308 pagesKorean Phrase BookCote Cabrera100% (7)

- 01 Speaking Korean For BeginnersDocument16 pages01 Speaking Korean For BeginnersCarmen Radu68% (25)

- 01 Speaking Korean For BeginnersDocument16 pages01 Speaking Korean For BeginnersCarmen Radu68% (25)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- What A Wonderful WorldDocument2 pagesWhat A Wonderful WorldDraganaNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6021 Assessment 1 Concept MapDocument7 pagesNURS FPX 6021 Assessment 1 Concept MapCarolyn HarkerNo ratings yet

- SATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...Document55 pagesSATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...arquivoslivrosNo ratings yet

- Grammar: English - Form 3Document39 pagesGrammar: English - Form 3bellbeh1988No ratings yet

- Especificação - PneusDocument10 pagesEspecificação - Pneusmarcos eduNo ratings yet

- Agrarian ReformDocument40 pagesAgrarian ReformYannel Villaber100% (2)

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDocument2 pagesCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytNo ratings yet

- Student Management System - Full DocumentDocument46 pagesStudent Management System - Full DocumentI NoNo ratings yet

- Succession CasesDocument17 pagesSuccession CasesAmbisyosa PormanesNo ratings yet

- Sussex Free Radius Case StudyDocument43 pagesSussex Free Radius Case StudyJosef RadingerNo ratings yet

- WRAP HandbookDocument63 pagesWRAP Handbookzoomerfins220% (1)

- Techniques of Demand ForecastingDocument6 pagesTechniques of Demand Forecastingrealguy789No ratings yet

- The Development of Poetry in The Victorian AgeDocument4 pagesThe Development of Poetry in The Victorian AgeTaibur Rahaman0% (1)

- COSL Brochure 2023Document18 pagesCOSL Brochure 2023DaniloNo ratings yet

- 2-Emotional Abuse, Bullying and Forgiveness Among AdolescentsDocument17 pages2-Emotional Abuse, Bullying and Forgiveness Among AdolescentsClinical and Counselling Psychology ReviewNo ratings yet

- CASE: Distributor Sales Force Performance ManagementDocument3 pagesCASE: Distributor Sales Force Performance ManagementArjun NandaNo ratings yet

- Use Reuse and Salvage Guidelines For Measurements of Crankshafts (1202)Document7 pagesUse Reuse and Salvage Guidelines For Measurements of Crankshafts (1202)TASHKEELNo ratings yet

- 2U6 S4HANA1909 Set-Up EN XXDocument10 pages2U6 S4HANA1909 Set-Up EN XXGerson Antonio MocelimNo ratings yet

- Task 2 - The Nature of Linguistics and LanguageDocument8 pagesTask 2 - The Nature of Linguistics and LanguageValentina Cardenas VilleroNo ratings yet

- DLL Week 7 MathDocument7 pagesDLL Week 7 MathMitchz TrinosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14ADocument52 pagesChapter 14Arajan35No ratings yet

- Army War College PDFDocument282 pagesArmy War College PDFWill100% (1)

- Bimetallic ZN and HF On Silica Catalysts For The Conversion of Ethanol To 1,3-ButadieneDocument10 pagesBimetallic ZN and HF On Silica Catalysts For The Conversion of Ethanol To 1,3-ButadieneTalitha AdhyaksantiNo ratings yet

- Green IguanaDocument31 pagesGreen IguanaM 'Athieq Al-GhiffariNo ratings yet

- Highway Capacity ManualDocument13 pagesHighway Capacity Manualgabriel eduardo carmona joly estudianteNo ratings yet

- 06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalDocument38 pages06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalSanjay KashyapNo ratings yet

- Boylestad Circan 3ce Ch02Document18 pagesBoylestad Circan 3ce Ch02sherry mughalNo ratings yet

- Peer-to-Peer Lending Using BlockchainDocument22 pagesPeer-to-Peer Lending Using BlockchainLuis QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey 2023 2Document510 pagesEconomic Survey 2023 2esr47No ratings yet

- Trainee'S Record Book: Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Your Institution)Document17 pagesTrainee'S Record Book: Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Your Institution)Ronald Dequilla PacolNo ratings yet