0% found this document useful (0 votes)

390 views58 pagesDeterrence Theory

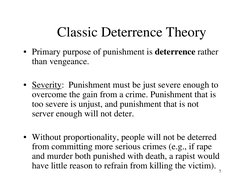

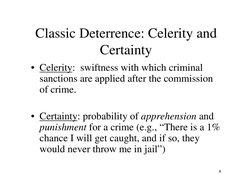

Rational choice theory views criminal behavior as a choice made by weighing costs and benefits. It assumes people rationally choose to commit crimes if the perceived rewards outweigh the risks of punishment. Empirical tests examine how crime rates relate to objective measures of punishment certainty, severity, and celerity. While some studies found capital punishment reduced homicide, others found no effect or even increases. Perceptual measures of punishment also relate to self-reported criminal behavior, though causation is unclear. Informal social controls may be stronger deterrents than formal legal sanctions.

Uploaded by

elan de noirCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

390 views58 pagesDeterrence Theory

Rational choice theory views criminal behavior as a choice made by weighing costs and benefits. It assumes people rationally choose to commit crimes if the perceived rewards outweigh the risks of punishment. Empirical tests examine how crime rates relate to objective measures of punishment certainty, severity, and celerity. While some studies found capital punishment reduced homicide, others found no effect or even increases. Perceptual measures of punishment also relate to self-reported criminal behavior, though causation is unclear. Informal social controls may be stronger deterrents than formal legal sanctions.

Uploaded by

elan de noirCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

- Introduction to Theories of Crime

- Deterrence Theory

- Empirical Evidence and Critique

- Rational Choice Theory

- Routine Activities Theory