Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An overview of 7 types of contemporary American rodeo

Uploaded by

BrettOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

An overview of 7 types of contemporary American rodeo

Uploaded by

BrettCopyright:

Available Formats

AN OVERVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY Rodeo Association), senior (National Senior Pro Rodeo

AMERICAN RODEO Association), gay (International Gay Rodeo Association),

and military (Military Rodeo Cowboys Association).

These associations were selected for two reasons.

Although each is the only national or international

Gene L. Theodori organization of its kind, none has been systematically

studied. Also, the emergence of these associations appear

Research Assistant, Department of Agricultural Economics to have paralleled important societal changes that have

and Rural Sociology, Penn State University, 301 Armsby occurred since the turn of the century.

Building, University Park, PA 16802 This paper extends work on rodeo begun by

anthropologists. It identifies and describes the organization

of different types of contemporary rodeo in terms of its

Abstract: Impromptu roping, riding, and racing affairs and participants, structure, and activities (Olsen 1968). It also

western pageantries whetted public appetites for a examines the functions (i.e., the contributions rodeos make

competitive cowboy sport. Despite its increasing to the communities in which they are staged) and possible

popularity and types, American rodeo has received little dyshnctions rodeos perform. The history of rodeo is

attention from social scientists. This paper discusses seven discussed first, followed by an identification and

different types of contemporary rodeo-professional, description of the organization of various types of rodeo.

women's, collegiate, high school, senior, gay, and Lastly, ideological, economic, and social functions of rodeo

military-and their common historical origin. The are discussed.

popularity of rodeo in contemporary society is attributed to

prevalent agrarian beliefs and the rural mystique among the Data for this study were collected using archival and

public and to a long line of promoters and organizers who historical investigation, document analyses, and in-depth

have increasingly commodified it. interviewing of representatives of selected rodeo

associations and unique types of rodeo. Furthermore,

Introduction community-level data (e.g., economic impact estimates)

Rodeo is one of America's fastest growing sports. Because were obtained through telephone conversations with

of its sociological and economic significance, rodeos have representatives of chambers of commerce and professional

been held in all 50 states. Today, the PRCA is the most organizations in communities that conduct a rodeo

dominant association in rodeo, with nearly 10,000 association's finals or championship rodeo.

members, including contestants, stock contractors,

bullfighters, and other non-contestant members (PRCA Origins of rodeo

Media Guide 1995). In 1994 the PRCA sanctioned 782 Lawrence (1982) and Fredriksson (1985), among other

rodeos in 46 states and 4 Canadian Provinces, in which a rodeo writers, assert that the origin of rodeo and its

total of 9,761 PRCA card holders and permit holders contemporary types is rooted in a combination of elements

competed for $23,063,793 in prize money (PRCA Media traceable to two post-Civil War era activities: (1) the

Guide 1995). In 1990, according to Weisman (1991), the roping, riding, and racing exhibitions staged among

PRCA and the International Professional Rodeo working cowboys for entertainment, and (2) the wild west

Association (IPRA) together sanctioned 1,100 rodeos, shows.

which attracted 18 million spectators and produced $80 Rodeo evolved as a natural result of the cowboy's need for

million in ticket sales. Like other professional sports, play and recreation (see Deaton 1952; Kegley 1942;

PRCA rodeo, and to a lesser degree IPRA rodeo, has Norbury 1993). After months of strenuous labor moving

become recognized in the athletic mainstream due to an cattle throughout the country, cowboys would get together

increase in media exposure and major corporate and celebrate. For amusement at the end of the trail,

sponsorship. However, many other rodeo associations hold cowboys would gather and compare their roping and riding

thousands of rodeos each year of which social scientists skills. These early celebrations were exhibitions; they were

know little about. a place where cowboys could show off the skills they had

acquired on the range. Soon afterwards, though, these

Contemporary American rodeo has many organizational exhibitions turned into competitive matches, staged among

types (i.e., professional, collegiate, high school, youth, both intra-ranch and inter-ranch cowboys. Impromptu

women's, gay, black, Indian, senior, prison, military, ranch, competitions became commonplace as cowboys competed

and others). With the exception of LeCompte's (1989% for their share of the prize pot, or at other times simply

1989b, 1990, 1993) studies on the Women's Professional "just for the hell or glory of it" (Durham and Jones 1965:

Rodeo Association and Dubin's (1989) ethnography of 206). As Lawrence (1982) noted, these early contests were

Native American rodeo, types of rodeo other than PRCA one element in the dual origin of American rodeo.

rodeo have been ignored in the scientific literature. The

types of rodeo examined here include: women's (Women's The other element in the genesis of American rodeo was

Professional Rodeo Association/Professional Women's the development of the wild west show. William F. Cody,

Rodeo Association), collegiate (National Intercollegiate better known as "Buffalo Bill," introduced the public to a

Rodeo Association), high school (National High School new type of outdoor entertainment. After a decade as a

producer and star of Western melodramas, Cody returned groups, complete with producers, announcers, livestock,

to his hometown of North Platte, Nebraska, in 1882. Upon and an assortment of cowboys and cowgirls, began staging

hearing that nothing was planned in observance of fake rodeos, simply rotating the victories among themselves

Independence Day, Cody arranged to hold an "Old Glory (LeCompte 1993). The combination of these elements

Blowout" on the Fourth of July. He persuaded local quickly began to undermine the status of legitimate

business owners to offer prizes for roping, shooting, riding, producers and rodeos. If rodeo was going to maintain its

and bronco breaking exhibitions, and sent out 5,000 popularity, some type of organization and coordination

handbills inviting local cowboys to partake (Russell 1970). among rodeo committees was necessary.

Cody projected that he might get 100 cowboy entrants;

however, he got 10 times that number (Russell 1970). In Historical data revealed that the sport of rodeo lacked

May of the following year, Cody staged an even larger centralized control throughout the early decades of the

extravaganza in his home state at the Omaha Fair Grounds. twentieth century. Each rodeo was conducted individually

This two-day Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition with its own rules and regulations, and there was no

attracted eight thousand spectators the first day and nine assurance beyond the spoken word of organizers that the

thousand the second (Fredriksson 1985). After his second *

winners would be paid. As a response to these and other

successful performance, Cody decided to turn this new extant concerns, rodeo managers formed in 1929 the Rodeo

form of live entertainment into a commercial enterprise, Association of America (RAA) to standardize rules and the

and announced that he was taking his show on the road conditions under which rodeos were held. Rodeo cowboys

(Fredriksson 1985). organized in 1936 the Cowboys Turtle Association (CTA)

to further safeguard the interests of the contestants.'

Cody sold his Wild West to U.S. and European audiences Through the efforts of both the Rodeo Association of

as an authentic representation of life as it existed on the America, which no longer exists, and the Cowboys Turtle

Association, rodeo became solidly established. The CTA

vanishing American frontier. His show included a cast of

Indians, homesteaders, skilled sharpshooters, stagecoach reorganized on March 15, 1945, and became known as the

drivers, scouts, trick riders, rough riders, and a mounted Rodeo Cowboys Association (RCA), which in 1975

cavalry. Audiences were thrilled with exciting exhibitions changed its name to the Professional Rodeo Cowboys

such as an attack on the Deadwood stagecoach, a Grand Association (PRCA).

Hunt on the Plains, and the crowd pleasing "Cow-Boy

Fun" events, the roping and riding exhibitions by daring Current rodeo

cowboys (Harris 1986). Other entrepreneurs also saw The efforts by the cowboys to protect themselves from

fraudulent producers and promoters, to collectively

economic advantage in staging similar shows. Such shows

were aimed primarily at Eastern city dwellers and represent their interests, and to improve their standard of

Europeans who were unfamiliar with the "cowboy culture" living paralleled similar demands made by past American

of the West. By 1885, the number of traveling shows labor movements (Dulles 1949; Lieberman 1986; Rayback

totaled more than fifty (Fredriksson 1985). Russell (1970) 1966; Taft 1964). Since the formation of the parent

identified 116 wild west shows that existed between 1883 contestants' organization, various non-mainstream rodeo

and 1944, yet noted that his list might be incomplete. associations have formed on local, state, regional, national,

and international levels. An analysis of the evolution of the

Early informal cowboy exhibitions and contests and the various types of rodeo from an epigenetic perspective

wild west shows were closely related. Accordingly, (Etzioni 1963) showed that each had hnctional elements

Westermeier (1947: 37) asserted that "[tlhe riders of those that distinguished it from its mainstream professional

counterpart (Theodori 1996). The "initiation" and

early shows were, or had been, working cowboys..." By

the late 1880s, with changing practices in the range-cattle institutionalization of each type of rodeo is marked by

industry, many working cowboys were becoming seasonal outward and visible signs closely resembling those of the

ranch employees. During the winter months, out-of-work women's movement (Deckard 1983; De Leon 1988;

cowboys found employment as bartenders, butchers, or Howard 1974), the gay liberation movement (Adam 1995;

De Leon 1988; Howard 1974; Marcus 1992), the senior or

blacksmiths (Forbis 1973; Harris 1986). Others found

employment with the traveling shows (Fredriksson 1985). "gray" movement (De Leon 1988; Wallace and Williamson

For approximately forty years, until their demise after 1992), and the growth of recreation and leisure time in

World War I, the wild west shows employed out-of-work contemporary society (Dulles 1965; Rader 1990; Swanson

cowboys. and Spears 1995). Several types originated to combat the

latent issues of age, racial, ethnic, and gender

Early organization discrimination in early rodeo. Others developed to satis@

In the early 1900s, interest in the wild west shows began to the urge to compete and/or encourage participation in the

wane. Conversely, at that time the popularity of rodeo sport by particular groups in society.

exploded. The 1920s was a period of rapid growth for Members of the Professional Women's Rodeo Association

rodeo, as producers began staging contests in cities and (PWRA) compete in 5 standard events which include

towns throughout the country. With this tremendous

expansion came a period of rampant disorganization.

Fraudulent producers failed to pay the winning contestants; The cowboys called themselves "Turtles" because they

rules and events lacked uniformity. Furthermore, touring were Slow but sure' to organize.

bareback bronc riding (6 second ride), bull or steer riding riding (7 second ride), steer wrestling, calf roping, and

(6 second ride), breakaway calf roping, tie down calf team roping. Women compete in the ladies barrel race, and

roping, and team roping. Goat tying, steer undecorating, with men in ribbon roping. In the bareback bronc riding,

and steer stopping may be included in PWRA rodeos as saddle bronc riding, and bull riding events, all contestants

optional events. The PWRA annually takes the top 15 compete in one age category, 40 and over, for the same

point earners in each of the 5 standard events to the PWRA prize money. Points, however, in those three riding events

National Finals. are awarded to the top six contestants in two age groups:

40-50 and 50 and over. Contestants in the steer wrestling

There are 9 standard events in National Intercollegiate event compete for prize money and points in two age

Rodeo Association (NIRA) rodeo competition for which groups, 40-50 and 50 and over. The remaining four events

points are awarded-five men's events, three women's consist of three age categories: 40-50, 50-60, and 60 and

events, and one men's/women's event. Men's events older. Purse money is divided equally among the age

include: bareback bronc riding (8 second ride), saddle groups, and points are awarded to the top six contestants in

bronc riding (8 second ride), bull riding (8 second ride), each category. At the end of each rodeo season, the

calf roping, and steer wrestling. Women's events include: National Senior Pro Rodeo Association (NSPRA) holds the

barrel racing, breakaway calf roping, and goat tying. Team National Senior Pro Rodeo Finals (NSPRF) to determine

roping is the one event in which men and women can event champions and name a men's and women's all-

compete together. At the end of the school year, qualifying around champion in each age category.2 The top 30

teams and individuals meet at the College National Finals contestants in the standings of each age category in the

Rodeo (CNFR) to determine national champions. In order timed events, with the exception of steer wrestling which is

to qualify for the team competition at the CNFR, teams limited to the top 20, and the combined top 20 contestants

must place either first or second in the final regional in the riding events are eligible to enter the finals, provided

standings, based on the total points accumulated at the ten certain requirements have been met. Requirements include

regional rodeos. Individuals also must have placed first or participation in at least five sanctioned rodeos and the

second in the final standings in an event or the all-around accumulation of at least ten points over the course of the

to qualifj for the CNFR. Both team champions and season.

individual champions are determined by points won at the

CNFR. Currently, the NIRA is divided into 11 regions A standard International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA)

(Theodori 1996). At the end of the 1994-1995 academic rodeo includes 13 events divided into four categories-

year, individual student membership in the NIRA totaled rough stock, roping, speed, and camp events. Rough stock

3,196, among 133 participating collegiate rodeo clubs. events include: bull riding (6 second ride), steer riding (6

Basic membership requirements include: attending an second ride), bareback bronc riding ( 6 second ride), and

accredited institution of post secondary education, chute dogging. Roping events include: team roping,

enrollment in at least 12 credit hours each semester (9 of mounted breakaway calf roping, and calf roping on foot.

which must be academic credits), and maintaining at least a Speed events include: barrel race, flag race, and pole

2.0 grade point average. Students are eligible to purchase bending. Camp events include: steer decorating, goat

four NIRA membership cards over a six-year period from dressing, and wild drag race. Males and females compete

the date of their high school graduation. together in all events. However, they are judged separately

in all events except in team events, which includes the three

There are 12 standard events in the National High School camp events and team roping. At the end of the rodeo

Rodeo Association (NHSRA)--five boys' events, five season, the top 5 contestants in each Division (Theodori

girls' events, and two coed events. Cowboys' events 1996) in each event are invited to compete in the IGRA

include: bareback bronc riding (8 second ride), saddle Rodeo Finals. Event champions and both the all-around

bronc riding (8 second ride), bull riding (8 second ride), cowboy and all-around cowgirl are determined based on

calf roping, and steer wrestling. Cowgirls' events include: points earned at the IGRA Rodeo Finals.

barrel racing, pole bending, goat tying, breakaway roping, Contestants must be members of the Military Rodeo

and the queen contest. The coed events include team Cowboys Association (MRCA) and have active duty status,

roping and cutting. The top four contestants in each event active reserve status, retired from active duty, or be a

at the state or province level qualify for the National High dependent of any active duty or retired member of the

School Finals Rodeo (NHSFR). In the queen contest, Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, National Guard, or

however, only one contestant from each state or province Coast Guard to compete in a MRCA rodeo. Standard

can qualify for the NHSFR. The NHSRA does not offer MRCA events include: bareback bronc riding (8 second

cash awards to event winners. Instead, students compete ride), saddle bronc riding (8 second ride), bull riding (8

for scholarships and prizes donated by major corporate second ride), calf roping, steer wrestling, chute dogging,

sponsors. Each year at the NHSFR, students compete for team tying, and barrel racing. Women can compete in all

college scholarships totaling in excess of $106,000. events; however, they generally participate only in barrel

racing.

Senior rodeo contestants compete in 8 standard events-six

of which are for men, one for women, and one for both men

and women. Men's events include: bareback bronc riding Points won by men in ribbon roping do not count towards

(7 second ride), saddle bronc riding (7 second ride), bull the all-around title.

Discussion blend of fact and imagination, was one element that linked

Ideological, economic, and social functions permeate them to their cultural heritage in a rapidly changing society.

contemporary American rodeo. The symbolic content of By the early 1920s, rodeo surpassed the stage of being a

rodeo is embedded in an agrarian ideology rooted deeply in small-time attraction in rural Western communities, as

American culture. The dissemination and mobilization of producers and promoters, driven by economic motives,

the agrarian value system in America is credited to the removed the cowboy sport from its regional origins and,

writings of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's articulation of like the wild west entrepreneurs, wrapped the rural Western

the agrarian creed nourished a belief system advocating that epic into a marketable commodity and sold it to eastern

there is a morally virtuous quality attached to agriculture, urbanites in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.

and that rural life is the natural and good life (see Dalecki

and Coughenour 1992). Although the United States has Contemporary rodeo is big business. In fact, as early as

become increasingly urbanized throughout the twentieth 1936, the terms "Big-Time Business" and "Big-Time

century, the American public continues to identi@ with Sport" were applied to rodeo (see Clinton 1936).

and endorse fundamental agrarian principles. Several Professional contestants, contract personnel, arena workers,

studies (e.g., Butte1 and Flinn 1975; Dalecki and and concessionaires depended wholly or partially on rodeo

Coughenour 1992; Flinn and Johnson 1974; Molnar and for their earnings. Moreover, rodeo stimulates economic

Wu 1989) have found that an agrarian ideology continues growth in other economic sectors (e.g., the western apparel

to be widespread among the American public. and the Quarter Horse industries). While most organizers

have not assessed the total economic impact of rodeos on

In a study of popular images of rurality among their community, several communities that host a finals

Pennsylvania residents, Willits et al. (1990) concluded that rodeo have estimated its economic impact. Las Vegas

people tend to associate positive images with rural life and estimated in 1995 that the PRCA's National Finals Rodeo

reject negative images of rurality. They termed this produced a $24.0 million economic impact, up slightly

imagery the rural mystique "because it involves an aura of from a $23.4 million economic impact in 1994 (telephone

treasured and almost sacred elements" (1990: 575). Rodeo conversation with Terry Jicinsky, Las Vegas Convention &

is part of the "rural mystique" and serves to preserve Visitors Authority). In 1995, Oklahoma City estimated that

America's rural Western narrative. To a degree, the rural the IPRA's International Finals Rodeo produced a $3.0

rodeo meta-narrative symbolizes what the West was, and million economic impact (telephone conversation with

concomitantly what our contemporary urban, industrialized Stanley Draper, Jr., Oklahoma City All Sports

society idealistically and romantically wishes it could Association). The estimated economic impact of the 1995

continue to be. As a ritual (see Stoeltje 1989, 1993), rodeo College National Finals Rodeo on Bozeman, Montana, was

perpetuates the late nineteenth-century Western frontier between $1.5 million and $2.0 million (telephone

ideology in contemporary American society. At a deeper conversation with Racene Friede, Chamber of Commerce,

level, symbolic themes, such as control and lack of control Bozeman, Montana). Obviously, not all communities that

over nature and the conquest of the "wild" West by an produce rodeos experience the level of economic impact

industrializing culture, are manifest in rodeo (Boatright associated with a finals rodeo.

1964; Errington 1990; Lawrence 1982).

The site for social action at a rodeo is the arena. Although

What began as athletic exhibitions and contests of the construction and location of arenas vary from

nineteenth-century range cowboys quickly became community to community, they provide actors (i.e.,

transformed into a marketable commodity. During the participants, employees, and spectators) with a setting to

second half of the 1800s, as commodification occurred in perform actions and form associations (Parsons 1951). So

grain, lumber, meat, and other trade goods (Cronon 1991), what motivates people to attend a rodeo? Among

Buffalo Bill and other wild west capitalists commodified numerous manifest reasons, the participants may be there

gloriously romantic and glamorous versions of the for the sport or athletic competition, the employees may be

American frontier. These entrepreneurs packaged the there out of economic necessity, and the spectators may be

culture of the nineteenth-century rural American West and there for the entertainment. On the other hand, rodeos

sold their frontier-Americana fabrications, complete with serve several other functions. For example, rodeos allow

longhorn cattle, savage Indians, and heroic cowboys, to people of different socioeconomic statuses to come

ranchless metropolitan markets on the east coast and in together momentarily and collectively identify with each

Europe. other. In short, although all rodeos share similar social

functions such as sport/athletic competition,

In the early 1900s, the popularity of this indigenous form recreationlleisure, and entertainment, each type maintains a

of American entertainment began to decline. Factors such functional niche that distinguishes it from its mainstream

as vaudeville, Hollywood, and new forms of transportation professional counterpart.

contributed to the demise of the Wild West Shows

(Johnson 1994). At the same time, interest in rodeo Closing comments

exploded. Cowboy contests were staged at Fourth of July Contemporary rural society is in a state of change.

celebrations and county and state agricultural fairs American rodeo, which evolved from the athletic

throughout the West. As industrial attributes from the East exhibitions and contests of the nineteenth-century range

infiltrated and affected Western cow towns, rodeo, with its cowboys and the wild west shows, is one institution that

fills the void in society created by the rural to urban Literature Cited

transformation in the United States. Although the days of Adam, Barry D. 1995. The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian

free riding, open range%great cattle drives, and unexplored Movement. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers.

frontiers have long past, positive images about agrarian

values, rural living, and the cowboy lifestyle have Boatright, Mody C. 1964. "The American Rodeo."

maintained a firm grip upon the minds and emotions of the American Quarterly 16:195-202.

American public. What does this mean? What does the

nostalgia of a supposedly simpler, more harmoniously, Buttel, Frederick H. and William L. Flinn. 1975. "Sources

pastoral way of life say about present-day American and Consequences of Agrarian Values in American

society? Society." Rural Sociology 40(2): 134-15 1.

Clinton, Bruce. 1936. "Rodeos: The New Big-Time

The challenge of the wild American West was once real.

Business and Sport." Hoofs and Horns 6(2): 17.

However, commodities such as dime novels, wild west

shows, folk songs, western movies, dude ranches, and

Cowboys Turtle Association. 1936. "Cowboys Turtle

rodeos have contributed to the widespread acceptance and

Association." Hoofs and Horns 6(7):24.

perpetuation of a rural American mystique. This mystique

is embellished by contemporary rodeo which packages

Cronon, William. 1991. Nature's Metropolis: Chicago

realistic notions and romantic sentiments of the Old West,

and the Great West New York, NY: W.W. Norton &

and sells the "frontier ethos" in small rural towns and major

Company.

urban centers across the country. The western frontier has

ceased to exist, but cowboys and rodeos remain a vibrant

Dalecki, Michael G. and C. Milton Coughenour. 1992.

part of the rural landscape.

"Agrarianism in American Society." Rural Sociology

57(1):48-64.

In closing, the purpose of this paper has been to provide an

overview of contemporary American rodeo. The foregoing Deaton, M.L. 1952. The History of Rodeo. Master's

analysis shed some insights into the structure, functions, Thesis, The University of Texas.

and possible dysfunctions of the various types of rodeo.

Nevertheless, many questions remain. A more thorough Deckard, Barbara Sinclair. 1983. The Women's

examination of the relationship between former societal Movement: Political, Socioeconomic, and Psychological

movements and the institutionalization of the different Issues. New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers.

types of rodeo should be conducted. Likewise, in-depth

case studies would provide valuable information on the De Leon, David. 1988. Everything Is Changing:

symbolic and functional utilities of each type. Contemporary U.S. Movements in Historical Perspective.

New York, NY: Praeger Publishers.

Additional studies should also address such important Dubin, Margaret. 1989. Cowboys and Indians: An

sociological issues as the demographics of rodeo Interpretation of Native American Rodeo. Honors Thesis,

contestants, the socioeconomic characteristics of rodeo Harvard University.

contestants, supporting participants (i.e., announcers,

clowns, bullfighters, arena workers, specialty-act Dulles, Foster Rhea. 1949. Labor in America. New York,

performers), and spectators. An overwhelming majority of NY: Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

people who participate in rodeo do so as hobbyists or part-

time rodeo contestants. Surveys could collect data on place . 1965. A History of Recreation: America Learns

of residency (rurallurban), primary occupation, annual to Play. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

income, educational level, and motivation of rodeo

participants and spectators. Furthermore, research Durham, Philip and Everett L. Jones. 1965. The Negro

addressing the publicity, attraction, and kind of corporate Cowboys. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Company.

sponsorship and the influence that these sponsors have

upon the decisions and choices of individuals in the rodeo Errington, Frederick. 1990. "The Rock Creek Rodeo:

marketplace is needed. Economic impact studies on rodeos Excess and Constraint in Men's Lives." American

other than finals rodeos could provide valuable Ethnologist 17:628-645.

community-level data regarding ways that rodeo

contributes to the viability and sustainability of rural Etzioni, Amitai. 1963. "The Epigenesis of Political

communities. Lastly, the specific manner and degree in Communities at the International Level." The American

which contemporary rodeo relates to fundamental agrarian Journal of Sociology 64:407-421.

attitudes and values in our society needs elaboration if rural

sociologists are to more fully understand the symbolic Flinn, William L. and Donald E. Johnson. 1974.

meanings and mechanisms that the public attaches to the "Agrarianism Among Wisconsin Farmers." Rural

rural mystique. Sociology 39(2): 187-204.

Forbis, William H. 1973. The Cowboys. New York, NY: Parsons, Talcott. 1951. The Social System. New York,

Time-Life Books. NY: The Free Press.

Fredriksson, Kristine. 1985. American Rodeo: From Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. 1995. Media

Buffalo Bill to Big Business. College Station, TX: Texas Guide of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association.

A&M University Press. Colorado Springs, CO: PRCA.

Harris, Bill. 1986. Cowboys: America's Living Legend. Rader, Benjamin G. 1990. American Sports: From the

New York, NY: Crescent Books. Age of Folk Games to the Age of Televised Sports.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Howard, John R. 1974. The Cutting Edge: Social

Movements and Social Change in America. Philadelphia, Rayback, Joseph G. 1966. A History of American Labor.

PA: J.B. Lippincott Company. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

International Gay Rodeo Association. 1996. IGRA 1996 Rodeo Association of America. 1940. "Rodeo Association

By-Laws. Denver, CO: IGRA. of America." Hoofs and Horns 9(10): 17-19.

Johnson, C. 1994. Guts: Legendary Black Rodeo Cowboy Russell, Don. 1970. The Wild West. Fort Worth, TX:

Bill Pickett. Fort Worth, TX: The Summit Group. The Amon Carter Museum of Western Art.

Kegley, Max. 1942. Rodeo: The Sport of the Cow Stoeltje, Beverly June. 1979. Rodeo as Symbolic

Country. New York, NY: Hastings House. Performance. Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms

International.

Lawrence, Elizabeth Atwood. 1982. Rodeo: An

Anthropologist Looks at the Wild and the Tame. . 1989. "Rodeo: From Custom to Ritual." Western

Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press. Folklore 48:244-256.

LeCompte, Mary Lou. 1989a. "Cowgirls at the . 1993. "Power and Ritual Genres: American

Crossroads: Women in Professional Rodeo: 1885-1922." Rodeo." Western Folklore 52: 135-156.

Canadian Journal of History of Sport 20:27-48.

Swanson, Richard A. and Betty Spears. 1995. History of

. 1989b. "Champion Cowgirls of Rodeo's Golden Sport and Physical Education in the United States.

Age." Journal of the West 28:88-94. Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark Publishers.

. 1990. "Home on the Range: Women in Tafl, Philip. 1964. Organized Labor in American History.

Professional Rodeo: 1929-1947." Journal of Sport History New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers.

17:3 18-346.

Theodori, Gene L. 1996. A Study of the Social

. 1993. Cowgirls of the Rodeo: Pioneer Organization of Contemporary American Rodeo. Master's

Professional Athletes. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Thesis, Texas A&M University.

Press.

Wallace, Steven P. and John B. Williamson. 1992. The

Lieberman, Sima. 1986. Labor Movements and Labor Senior Movement: References and Resources. New York,

Thought: Spain, France, Germany, and the United States. NY: G.K. Hall & Co.

New York, NY: Praeger Publishers.

Weisman, K. 1991. "Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to

Marcus, Eric. 1992. Making History: The Struggle for Be Cowboys." Forbes 147:122-123.

Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945-1990: An Oral

History. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers. Westermeier, Clifford P. 1946. The History of Rodeo.

Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Colorado.

Molnar, Joseph J. and Litchi S. Wu. 1989. "Agrarianism,

Family Farming, and Support for State Intervention in . 1947. Man, Beast, Dust: The Story of Rodeo.

Agriculture." Rural Sociology 54(2):227-245. Denver, CO: The World Press, Inc.

Norbury, Rosamond. 1993. Behind the Chutes: The . 1955. Trailing the Cowboy. Caldwell, ID: The

Mystique of the Rodeo Cowboy. Missoula, MT: Mountain Caxton Printers, LTD.

Press Publishing Co.

Willits, Fern K., Robert C. Bealer, and Vincent L. Timbers.

Olsen, Marvin Elliott. 1968. The Process of Social 1990. "Popular Images of 'Rurality': Data from a

Organization. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Pennsylvania Survey." Rural Sociology 55(4):559-578.

Winston, Inc.

You might also like

- The New Black West: Photographs from America's Only Touring Black RodeoFrom EverandThe New Black West: Photographs from America's Only Touring Black RodeoNo ratings yet

- In and Around the Arena: The 100-Year History of the Fortuna RodeoFrom EverandIn and Around the Arena: The 100-Year History of the Fortuna RodeoNo ratings yet

- Kings of the Road: How Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers, and Alberto Salazar Made Running Go BoomFrom EverandKings of the Road: How Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers, and Alberto Salazar Made Running Go BoomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Brewing a Boycott: How a Grassroots Coalition Fought Coors and Remade American Consumer ActivismFrom EverandBrewing a Boycott: How a Grassroots Coalition Fought Coors and Remade American Consumer ActivismNo ratings yet

- The Enduring Legacy of the Detroit Athletic Club: Driving the Motor CityFrom EverandThe Enduring Legacy of the Detroit Athletic Club: Driving the Motor CityNo ratings yet

- Athletes for Racial Equity: Jackie Robinson, Arthur Ashe, and MoreFrom EverandAthletes for Racial Equity: Jackie Robinson, Arthur Ashe, and MoreNo ratings yet

- The Young and the Rodeo: A Tale of How Young People Keep Alive the Sport of Rodeo in the Region Called the ArklamissFrom EverandThe Young and the Rodeo: A Tale of How Young People Keep Alive the Sport of Rodeo in the Region Called the ArklamissNo ratings yet

- Eight-Wheeled Freedom: The Derby Nerd’s Short History of Flat Track Roller DerbyFrom EverandEight-Wheeled Freedom: The Derby Nerd’s Short History of Flat Track Roller DerbyNo ratings yet

- The Olympics that Never Happened: Denver '76 and the Politics of GrowthFrom EverandThe Olympics that Never Happened: Denver '76 and the Politics of GrowthNo ratings yet

- The All-American Soap Box Derby: A Review of the Formative Years 1938 Thru 1941From EverandThe All-American Soap Box Derby: A Review of the Formative Years 1938 Thru 1941No ratings yet

- The Abcs of RotaryDocument34 pagesThe Abcs of RotaryKanwal NainNo ratings yet

- Rotary Awareness Quiz Answer SheetDocument3 pagesRotary Awareness Quiz Answer SheetantaghiNo ratings yet

- Reinventing Rhetoric Scholarship: Fifty Years of the Rhetoric Society of AmericaFrom EverandReinventing Rhetoric Scholarship: Fifty Years of the Rhetoric Society of AmericaNo ratings yet

- National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly that Strangled Professional WrestlingFrom EverandNational Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly that Strangled Professional WrestlingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- A Historical Investigation Into Rodeo MasbatenoDocument3 pagesA Historical Investigation Into Rodeo MasbatenoJimi BarrugaNo ratings yet

- Race across America: Eddie Gardner and the Great Bunion DerbiesFrom EverandRace across America: Eddie Gardner and the Great Bunion DerbiesNo ratings yet

- Joining the Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945From EverandJoining the Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- LA Sports: Play, Games, and Community in the City of AngelsFrom EverandLA Sports: Play, Games, and Community in the City of AngelsWayne WilsonNo ratings yet

- San Francisco Bay Area Sports: Golden Gate Athletics, Recreation, and CommunityFrom EverandSan Francisco Bay Area Sports: Golden Gate Athletics, Recreation, and CommunityNo ratings yet

- Pro Wrestling FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the World's Most Entertaining SpectacleFrom EverandPro Wrestling FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the World's Most Entertaining SpectacleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Stable Views: Stories and Voices from the Thoroughbred RacetrackFrom EverandStable Views: Stories and Voices from the Thoroughbred RacetrackNo ratings yet

- Baseball Road Trips: The Midwest and Great LakesFrom EverandBaseball Road Trips: The Midwest and Great LakesRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American AthletesFrom EverandOut of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American AthletesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Olimpismo: The Olympic Movement in the Making of Latin America and the CaribbeanFrom EverandOlimpismo: The Olympic Movement in the Making of Latin America and the CaribbeanNo ratings yet

- 07-05-2011 EditionDocument28 pages07-05-2011 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- George Dixon: The Short Life of Boxing's First Black World Champion, 1870–1908From EverandGeorge Dixon: The Short Life of Boxing's First Black World Champion, 1870–1908No ratings yet

- 100 Athletes Who Shaped Sports History: A Sports Biography Book for KidsFrom Everand100 Athletes Who Shaped Sports History: A Sports Biography Book for KidsNo ratings yet

- Stars For Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and The Civil Rights MovementDocument19 pagesStars For Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and The Civil Rights MovementUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Outlaws and Peace Officers: Memoirs of Crime and Punishment in the Old WestFrom EverandOutlaws and Peace Officers: Memoirs of Crime and Punishment in the Old WestRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Defending Community: The Struggle for Alternative Redevelopment in Cedar-RiversideFrom EverandDefending Community: The Struggle for Alternative Redevelopment in Cedar-RiversideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Detroit the Unconquerable: The 1935 Detroit Tiger: SABR Digital Library, #23From EverandDetroit the Unconquerable: The 1935 Detroit Tiger: SABR Digital Library, #23No ratings yet

- Horse Racing the Chicago Way: Gambling, Politics, and Organized Crime, 1837-1911From EverandHorse Racing the Chicago Way: Gambling, Politics, and Organized Crime, 1837-1911No ratings yet

- Rolling Thunder: The Golden Age of Roller Derby & the Rise and Fall of the L.A. T-BirdsFrom EverandRolling Thunder: The Golden Age of Roller Derby & the Rise and Fall of the L.A. T-BirdsNo ratings yet

- William L. Dulaney, "A Brief History of Outlaw' Motorcycle Clubs" International Journal of MotorcycleDocument14 pagesWilliam L. Dulaney, "A Brief History of Outlaw' Motorcycle Clubs" International Journal of Motorcycleapi-306766297No ratings yet

- CF Start Up Guide #1Document7 pagesCF Start Up Guide #1Black and Gold CrossFit100% (3)

- Escape Evasion PDFDocument9 pagesEscape Evasion PDFhiperion42No ratings yet

- Single Artist Song Release Date Chart Peak Other Charting Songs Chart PeakDocument1 pageSingle Artist Song Release Date Chart Peak Other Charting Songs Chart PeakBrettNo ratings yet

- Tough Mudder training guideDocument8 pagesTough Mudder training guideBrettNo ratings yet

- Workoutsforfatlossover 40Document4 pagesWorkoutsforfatlossover 40BrettNo ratings yet

- SurvingFedcoinBookweb VersionDocument139 pagesSurvingFedcoinBookweb VersionBrettNo ratings yet

- Joe Bonamassa - Going Down LickDocument1 pageJoe Bonamassa - Going Down LickMaurizioCorbinoNo ratings yet

- Country Solos #11 - Country Solos 11 - Only DaddyDocument3 pagesCountry Solos #11 - Country Solos 11 - Only DaddyBrettNo ratings yet

- .Board Policy 4.27 Home EdDocument3 pages.Board Policy 4.27 Home EdBrettNo ratings yet

- Country Solos #2 - Country Solos 2 - Working ManDocument2 pagesCountry Solos #2 - Country Solos 2 - Working ManBrettNo ratings yet

- Stedman Commentary NTBasicsDocument319 pagesStedman Commentary NTBasicsBrett100% (2)

- Imprimis March 2016Document6 pagesImprimis March 2016BrettNo ratings yet

- Simple Questions For The Honest JWDocument86 pagesSimple Questions For The Honest JWBrettNo ratings yet

- Printable FamilyTree - Printable FamilyTreeDocument1 pagePrintable FamilyTree - Printable FamilyTreeBrettNo ratings yet

- Finale 2003a - (In Your Face - Mus) - in - Your - FaceDocument6 pagesFinale 2003a - (In Your Face - Mus) - in - Your - FaceBrettNo ratings yet

- FIGURE 1 Zacky: Both Guitars Are in Drop-D Tuning (Low To High: D A D G B E)Document1 pageFIGURE 1 Zacky: Both Guitars Are in Drop-D Tuning (Low To High: D A D G B E)BrettNo ratings yet

- Betcha PetrucciDocument1 pageBetcha PetruccinaeslasNo ratings yet

- Roberts Quick Licks #30 Jeff LoomisDocument2 pagesRoberts Quick Licks #30 Jeff LoomisBrettNo ratings yet

- Understanding ModesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding ModesSalomon Cardeño LujanNo ratings yet

- Shred Lick Guitar TabDocument2 pagesShred Lick Guitar TabBrett100% (1)

- GA Business Document Key DetailsDocument1 pageGA Business Document Key DetailsBrett100% (1)

- Sweep PickingDocument10 pagesSweep PickingBrettNo ratings yet

- Print - Increasing Speed Licks - My Guitar Solo1Document6 pagesPrint - Increasing Speed Licks - My Guitar Solo1BrettNo ratings yet

- TabsDocument6 pagesTabsBrettNo ratings yet

- Guitar Lesson SweepingDocument5 pagesGuitar Lesson SweepingsuperflypeckerNo ratings yet

- Blues Licks For ShreddersDocument2 pagesBlues Licks For ShreddersBrettNo ratings yet

- Betcha PetrucciDocument1 pageBetcha PetruccinaeslasNo ratings yet

- FIGURE 1 Zacky: Both Guitars Are in Drop-D Tuning (Low To High: D A D G B E)Document1 pageFIGURE 1 Zacky: Both Guitars Are in Drop-D Tuning (Low To High: D A D G B E)BrettNo ratings yet

- Dianodic DN2301Document7 pagesDianodic DN2301dalton2004No ratings yet

- AI Quiz 3Document3 pagesAI Quiz 3Juiyyy TtttNo ratings yet

- AttentionDocument57 pagesAttentionSarin DominicNo ratings yet

- Innovation CultureDocument14 pagesInnovation Cultureapi-239073675No ratings yet

- GDS Online Engagement Application: Personal DetailsDocument3 pagesGDS Online Engagement Application: Personal DetailsAshutosh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Cisco uBR7100 Series Universal Broadband Router Software Configuration GuideDocument208 pagesCisco uBR7100 Series Universal Broadband Router Software Configuration GuideSamuel Caetano MerlimNo ratings yet

- Car ParkingDocument65 pagesCar Parkingmaniblp100% (1)

- Oracle Session Traffic LightsDocument13 pagesOracle Session Traffic Lightspiciul7001No ratings yet

- Design of A PID Controller For Disk Drive SystemDocument24 pagesDesign of A PID Controller For Disk Drive SystemshuvrabanikNo ratings yet

- Soal English Usbn 19Document8 pagesSoal English Usbn 19Gina Inayatul MaulaNo ratings yet

- Strategi Penerapan Eko-Drainase Di Kawasan Gampoeng Keuramat Banda AcehDocument8 pagesStrategi Penerapan Eko-Drainase Di Kawasan Gampoeng Keuramat Banda Acehherry arellaNo ratings yet

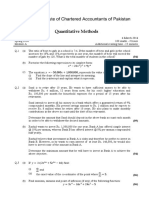

- Quantitative Methods Exam Focuses on Statistical AnalysisDocument3 pagesQuantitative Methods Exam Focuses on Statistical Analysissecret studentNo ratings yet

- PEE 2marks With AnswersDocument32 pagesPEE 2marks With AnswersSARANYANo ratings yet

- What I'Ve Learned: Robert de NiroDocument18 pagesWhat I'Ve Learned: Robert de NiroOrlando CrowcroftNo ratings yet

- Bai Tap CNTTDocument198 pagesBai Tap CNTTthanhthao124No ratings yet

- Read 9789351528463 Anatomy Amp Physiology For Paramedics and NursesDocument2 pagesRead 9789351528463 Anatomy Amp Physiology For Paramedics and NursesZohaib AliNo ratings yet

- Tekla OperatorsDocument26 pagesTekla OperatorsGaurav MevadaNo ratings yet

- NewsNWSARReportWEB PDFDocument117 pagesNewsNWSARReportWEB PDFAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- E1224Document3 pagesE1224Alejandro Garcia FloresNo ratings yet

- Ways to Earn Money LessonDocument3 pagesWays to Earn Money LessonSyarifahSyarinaSheikhKamaruzamanNo ratings yet

- ISCOM2824G Conifuguration20090519Document378 pagesISCOM2824G Conifuguration20090519Svetlin IvanovNo ratings yet

- In-Situ Fermentors CatalogueDocument4 pagesIn-Situ Fermentors CatalogueVineet GuptaNo ratings yet

- 0 Chhavi Gupta Resume PDFDocument3 pages0 Chhavi Gupta Resume PDFanon_630797665No ratings yet

- Intimations of ImmortalityDocument43 pagesIntimations of Immortalitygrobi69100% (1)

- Bar ChartDocument21 pagesBar Chartnoreen shahNo ratings yet

- Registration Fee Rs.500/-: PatronDocument2 pagesRegistration Fee Rs.500/-: PatronnathxeroxNo ratings yet

- 3rd MODIFIED OXFORD-OREGON DEBATEDocument5 pages3rd MODIFIED OXFORD-OREGON DEBATEDoc AemiliusNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Sheet To Be Filled by The Principal/Head Teacher For "Nation Builder Award" (Outstanding Teacher Award)Document1 pageEvaluation Sheet To Be Filled by The Principal/Head Teacher For "Nation Builder Award" (Outstanding Teacher Award)ckNo ratings yet

- Five Central Cognitive Processes in IL DevelopmentDocument3 pagesFive Central Cognitive Processes in IL DevelopmentLorena Vega LimonNo ratings yet

- THE JOURNAL Egyptian Archaeology - Plymouth City CouncilDocument20 pagesTHE JOURNAL Egyptian Archaeology - Plymouth City CouncilPopa ConstantinNo ratings yet