Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pci Versus Cabg in Cad, Serruys (2009)

Uploaded by

Henrique MachadoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pci Versus Cabg in Cad, Serruys (2009)

Uploaded by

Henrique MachadoCopyright:

Available Formats

new england

The

journal of medicine

established in 1812 march 5, 2009 vol. 360 no. 10

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention versus Coronary-Artery

Bypass Grafting for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

Patrick W. Serruys, M.D., Ph.D., Marie-Claude Morice, M.D., A. Pieter Kappetein, M.D., Ph.D.,

Antonio Colombo, M.D., David R. Holmes, M.D., Michael J. Mack, M.D., Elisabeth Ståhle, M.D.,

Ted E. Feldman, M.D., Marcel van den Brand, M.D., Eric J. Bass, B.A., Nic Van Dyck, R.N., Katrin Leadley, M.D.,

Keith D. Dawkins, M.D., and Friedrich W. Mohr, M.D., Ph.D., for the SYNTAX Investigators*

A bs t r ac t

Background

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) involving drug-eluting stents is increas- From Erasmus University Medical Center

ingly used to treat complex coronary artery disease, although coronary-artery bypass Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

(P.W.S., A.P.K., M.B.); Institut Cardiovas-

grafting (CABG) has been the treatment of choice historically. Our trial compared culaire Paris Sud, Massy, France (M.-C.M.);

PCI and CABG for treating patients with previously untreated three-vessel or left San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

main coronary artery disease (or both). (A.C.); Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

(D.R.H.); Medical City Hospital, Dallas

(M.J.M.); University Hospital Uppsala,

Methods

Uppsala, Sweden (E.S.); Evanston Hospi-

We randomly assigned 1800 patients with three-vessel or left main coronary artery tal, Evanston, IL (T.E.F.); Boston Scientif-

disease to undergo CABG or PCI (in a 1:1 ratio). For all these patients, the local car- ic, Marlborough, MA (E.J.B., N.V.D., K.L.,

K.D.D.); and Herzzentrum Universität

diac surgeon and interventional cardiologist determined that equivalent anatomical Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany (F.W.M.). Ad-

revascularization could be achieved with either treatment. A noninferiority compari- dress reprint requests to Dr. Serruys at

son of the two groups was performed for the primary end point — a major adverse the Erasmus University Medical Center,

Rotterdam, Gravendijkwal 230, 3015 CE

cardiac or cerebrovascular event (i.e., death from any cause, stroke, myocardial in- Rotterdam, the Netherlands, or at p.w.j.c.

farction, or repeat revascularization) during the 12-month period after randomiza- serruys@erasmusmc.nl.

tion. Patients for whom only one of the two treatment options would be beneficial,

*The other Synergy between Percutane-

because of anatomical features or clinical conditions, were entered into a parallel, ous Coronary Intervention with Taxus

nested CABG or PCI registry. and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) investi-

gators are listed in the Supplementary

Results Appendix, available with the full text of

this article at NEJM.org.

Most of the preoperative characteristics were similar in the two groups. Rates of

major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events at 12 months were significantly high- This article (10.1056/NEJMoa0804626) was

er in the PCI group (17.8%, vs. 12.4% for CABG; P = 0.002), in large part because of published on February 18, 2009, and up-

dated on February 7, 2013, at NEJM.org.

an increased rate of repeat revascularization (13.5% vs. 5.9%, P<0.001); as a result,

the criterion for noninferiority was not met. At 12 months, the rates of death and N Engl J Med 2009;360:961-72.

myocardial infarction were similar between the two groups; stroke was significantly Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society.

more likely to occur with CABG (2.2%, vs. 0.6% with PCI; P = 0.003).

Conclusions

CABG remains the standard of care for patients with three-vessel or left main coronary

artery disease, since the use of CABG, as compared with PCI, resulted in lower rates of

the combined end point of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events at 1 year.

(ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00114972.)

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 961

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

C

oronary-artery bypass grafting this group without adequate support from evi-

(CABG) was introduced in 1968 and rap- dence-based medicine and randomized clinical

idly became the standard of care for symp- trials.27

tomatic patients with coronary artery disease.1 Ad- In the Synergy between PCI with Taxus and

vances in coronary surgery (e.g., off-pump CABG, Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial, we assessed the

smaller incisions, enhanced myocardial preserva- optimal revascularization strategy for patients with

tion, use of arterial conduits, and improved post- previously untreated three-vessel or left main coro-

operative care) have reduced morbidity, mortality, nary artery disease and defined the populations

and rates of graft occlusion.2-6 of patients for whom only one revascularization

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was method will be effective.

introduced in 1977.7 Experience with this ap-

proach, coupled with improved technology, has Me thods

made it possible to treat increasingly complex le-

sions and patients with a history of clinically sig- Study Design

nificant cardiac disease, risk factors for coronary The SYNTAX trial is a prospective, clinical trial

artery disease, coexisting conditions, or anatomi- conducted in 85 sites and approved by the insti-

cal risk factors.8,9 Several trials comparing PCI in- tutional review board at each participating cen-

volving bare-metal stents with CABG in patients ter. The study had an “all-comers” design involv-

with multivessel disease (e.g., the Arterial Revas- ing the consecutive enrollment of all eligible

cularization Therapies Study Part I [ARTS I], the patients with three-vessel or left main coronary

Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study for Multi artery disease at sites in 17 countries in Europe

vessel Coronary Artery Disease [MASS II; Current and the United States. The study design has been

Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN66068876], described previously.28 Criteria for study and reg-

the Argentine Randomized Study of Coronary istry enrollment and outcome data are described

Angioplasty with Stenting versus Coronary By- in the Supplementary Appendix. The authors de-

pass Surgery in Patients with Multiple Vessel signed the study, as part of their role on the steer-

Disease [ERACI-II], and the Angina with Ex- ing committee, in collaboration with the sponsor,

tremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation Boston Scientific. The sponsor was involved in

[AWESOME]) showed similar survival rates but collection and source verification of the data, with

higher revascularization rates among patients oversight by an independent clinical events com-

with bare-metal stents at 5 years. Others have mittee. The sponsor’s biostatisticians performed

shown a significant long-term survival advan- the analyses; however, data analyses were verified

tage with surgery (e.g., the Stent or Surgery [SOS] independently by a statistician on the data and

study).10-12 Studies comparing PCI involving drug- safety monitoring committee. The authors wrote

eluting stents with CABG have generally been the manuscript and vouch for the completeness

smaller and nonrandomized.13-24 and accuracy of the data gathering and analysis.

Data from randomized, controlled trials of

drug-eluting stents as compared with bare-metal Selection and Randomization of Patients

stents have shown significant reductions in the A local interventional cardiologist and cardiac sur-

rate of repeat intervention, with similar rates of geon at each site prospectively evaluated eligible

death and myocardial infarction.25 These improve- patients with previously untreated three-vessel cor-

ments have led to expanded use of PCI in pa- onary disease and those with left main coronary

tients with complex coronary anatomical features, artery disease (alone or with one-, two-, or three-

though most randomized trials comparing drug- vessel disease). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are

eluting stents and bare-metal stents excluded such listed in the Methods section of the Supplemen-

patients. According to current guidelines,26 CABG tary Appendix. Patients in whom it was deter-

remains the treatment of choice for patients with mined that equivalent anatomical revasculariza-

severe coronary artery disease, including those tion could be achieved with either CABG or PCI

with left main coronary artery disease and those involving Taxus Express paclitaxel-eluting stents

with three-vessel disease. There is a lack of data (Boston Scientific) were randomly assigned to un-

from adequately powered randomized trials of PCI dergo one of the two treatment options by means

in such patients. Thus, PCI is being performed in of an interactive voice-responding system. Ran-

962 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

domization was stratified at each site according Primary End Point

to the presence or absence of left main coronary The primary clinical end point was a composite of

artery disease and medically treated diabetes (dia- major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

betes for which the patient was receiving oral hy- (i.e., death from any cause, stroke, myocardial in-

poglycemic agents or insulin at the time of en- farction, or repeat revascularization) throughout

rollment). Patients for whom only one treatment the 12-month period after randomization. An in-

option was suitable were entered into a parallel, dependent clinical events committee (including

nested registry: the PCI registry for CABG-ineligi- cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and a neurologist;

ble patients and the CABG registry for PCI-ineli- see the list in the Supplementary Appendix) adju-

gible patients. dicated all primary clinical end points, staged

All diagnostic angiograms and electrocardio- procedures, and cases in which the sternum was

grams were reviewed by staff at an independent reopened.

core laboratory (Cardialysis, Rotterdam, the Neth-

erlands) who were unaware of the treatment as- Statistical Analysis

signments. Diagnostic angiograms were scored, The primary analysis was a noninferiority com-

according to the SYNTAX score algorithm,29 at the parison of the two treatments for the primary

site and at the core laboratory. In addition, staff end point of adverse binary cardiac or cerebro-

at an independent central chemistry laboratory vascular events in all patients who underwent ran-

(Covance, Indianapolis and Geneva) who were un- domization (on an intention-to-treat basis). If the

aware of treatment assignments assessed selected one-sided 95% upper confidence limit for the dif-

variables. ference was less than the prespecified delta value

The institutional review board at each site ap- (6.6%), PCI with the drug-eluting stents would be

proved the protocol, and all patients provided considered to be noninferior to CABG in the over-

written informed consent. The protocol and con- all randomized cohort. The noninferiority margin

sent forms were consistent with the Food and was based on historical data (see the Methods sec-

Drug Administration’s Guidance for Industry E6 tion in the Supplementary Appendix). We calcu-

Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsin- lated the means (±SD) for continuous variables in

ki, the International Conference on Harmonisa- each of the two groups and compared them us-

tion, and all local regulations, as appropriate. ing Student’s t-test. Binary variables are reported

as counts and percentages, and differences be-

Revascularization and Pharmacologic tween the two groups were assessed by means of

Treatment the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Cumulative

Patients were treated with the intention of achiev- event rates were estimated by means of the Kap

ing complete revascularization of all vessels at lan–Meier method. In addition, the 12-month

least 1.5 mm in diameter with stenosis of 50% or rates of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular

more, as identified by the local interventional car- events were analyzed on the basis of the SYNTAX

diologist and cardiac surgeon. The surgical tech- score and compared with the use of a chi-square

nique for CABG, the approaches used for stent test. The SYNTAX score reflects a comprehensive

implantation, and the postprocedure medication anatomical assessment, with higher scores indi-

regimen were chosen according to local clinical cating more complex coronary disease; a low score

practice. In patients who underwent PCI, antiplate- was defined as ≤22, an intermediate score as 23

let medication was prescribed on the basis of the to 32, and a high score as ≥33 (see the Supple-

directions for use of the Taxus Express stent and mentary Appendix for details).

local clinical practice. In most centers, thienopyri-

dines were continued even after 6 months, with R e sult s

71.1% of patients receiving them at 12 months.

Aspirin was prescribed indefinitely for all patients Study Participants

who underwent randomization. Use of the stan- From March 2005 through April 2007, a total of

dard of postintervention care was recommended.30 4337 patients with previously untreated three-vessel

Procedural details are described in the Methods or left main coronary artery disease (or both) were

section of the Supplementary Appendix. screened (Fig. 1). After consideration by the local

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 963

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

interventional cardiologist and cardiac surgeon er with CABG than with PCI (Table 1). A higher

and after written informed consent was obtained, proportion of patients had complete revascular-

3075 patients (70.9%) were included in the study. ization after CABG than after PCI (63.2% vs.

Of these, 1800 patients were randomly assigned to 56.7%, P = 0.005). Medical management at dis-

undergo CABG (897 patients) or PCI with drug- charge differed between the CABG and PCI groups:

eluting stents (903 patients) at sites in the United patients who underwent CABG received less phar-

States (245 patients) and in Europe (1555 patients). macologic treatment, whereas those who under-

The reasons for exclusion of the remaining 1262 went PCI were consistently treated with antiplate-

patients are listed in Figure 1. Only one treatment let medications (Table 2). In the CABG group,

option was suitable in 1275 patients (29.4%), who off-pump surgery was performed in 15.0% of pa-

were enrolled in the nested registry for CABG (1077 tients, one or more arterial grafts were used in

patients) or PCI (198 patients). 97.3% of patients, and an average of 2.8 conduits

Patients in the two groups were well balanced and 3.2 distal anastomoses per patient were per-

with regard to most of the baseline demographic formed. In the PCI group, 14.1% of patients un-

and clinical characteristics (Table 1). The propor- derwent staged procedures, 63.1% had at least one

tion of patients with blood pressure of 130/80 bifurcation or trifurcation treated, more than four

mm Hg or higher was significantly larger in the stents on average were implanted per patient, and

PCI group. The numbers of current smokers, pa- a third of patients had placement of stents with

tients with elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg per a total length of more than 100 mm.

deciliter [1.7 mmol per liter]), and patients with A greater proportion of patients in the CABG

reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels registry had characteristics of severe lesions — in-

(<40 mg per deciliter [1.0 mmol per liter] for men cluding large proportions of patients with total

or <50 mg per deciliter [1.3 mmol per liter] for occlusion (56.4%), bifurcation (80.8%), lesions that

women) were higher in the CABG group. A total were more than 20 mm in length (31.5%), and

of 38.8% of patients in the CABG group and 39.5% heavy calcification (32.7%) — than in either ran-

of those in the PCI group had left main coronary domized group or the PCI registry (Table 2 in the

artery disease, with or without additional diseased Supplementary Appendix). Together with other

vessels. Approximately 25% of patients had medi- anatomical characteristics, these features resulted

cally treated diabetes, of whom about one third in an average raw SYNTAX score of 37.8±13.3

required insulin. Moreover, nearly half the pa- among the patients in the CABG registry (Table 2

tients (45.8%) met the criteria for the metabolic in the Supplementary Appendix). In contrast, the

syndrome.33 More than 20% of patients in both prevalence of cardiac risk factors and the preva-

groups were considered to be at high surgical lence of coexisting conditions were increased

risk, on the basis of a European System for Car- among patients enrolled in the PCI registry. A total

diac Operative Risk Evaluation (euroSCORE)31 of 30.2% of these patients had diabetes, 40.4% had

value of 6 or more (24.9% in the CABG group previously had a myocardial infarction, 19.3% had

and 24.7% in the PCI group, P = 0.94) and a Par- a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-

sonnet score32 of 15 or more (20.2% and 20.5%, ease, 14.1% had a history of transient ischemic

respectively; P = 0.87). attacks or stroke, and 4.7% were dependent on

Overall, more than 4 clinically significant coro- pacemakers — leading to average surgical scores

nary lesions were treated per patient (mean, 4.4 for that were higher than in the other groups of pa-

CABG and 4.3 for PCI); among all patients in both tients (euroSCORE value, 5.8±3.1; and Parsonnet

groups, total occlusion was identified in 23.1%, score, 14.4±9.5) (Table 2 in the Supplementary Ap-

and 72.8% had a bifurcation lesion (Table 1). These pendix).

results, together with other lesion characteristics,

resulted in an average raw SYNTAX score of 29.1 Primary Outcome

in the CABG group and 28.4 in the PCI group Preprocedural rates of major adverse cardiac or

(P = 0.19) (Table 1). cerebrovascular events were low and did not differ

The length of time between randomization and significantly between the two groups (0.9% in the

performance of the study procedure, the duration CABG group and 0.3% in the PCI group, P = 0.13)

of the procedure, and the duration of the post- (Table 6 in the Supplementary Appendix), as was

procedural hospital stay were significantly great- the case for in-hospital rates. The preprocedural

964 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

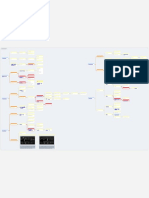

4337 Patients were assessed

for eligibility

1262 Were ineligible

408 Had a treatment preference

306 Declined to participate after providing

informed consent, or the referring

physician declined to accept the

patient’s consent

210 Met exclusion criteria

194 Declined to participate before providing

informed consent

79 Had other reason

51 Underwent medical treatment

14 Declined to undergo revascularization

1275 Were eligible only for enroll-

1800 Underwent randomization

ment in a parallel, nested registry

897 Were assigned to 903 Were assigned to 1077 Were enrolled 198 Were enrolled

undergo CABG undergo PCI in CABG registry in PCI registry

16 Underwent PCI 11 Underwent CABG

25 Underwent neither 6 Underwent neither

CABG nor PCI PCI nor CABG

12 Did not have data

48 Did not have data analyzed

analyzed 7 Were withdrawn

40 Were withdrawn 4 Were lost to follow-up

8 Were lost to 1 Was not treated

follow-up because inclusion

criteria were not met

849 (94.6%) Had data 891 (98.7%) Had data

analyzed analyzed

Figure 1. Enrollment and Randomization of Patients with Previously Untreated Three-Vessel or Left Main Coronary Artery Disease

in the SYNTAX Trial.

The trial used an “all-comers” design. Exclusion criteria were previous intervention, acute myocardial infarction, and concomitant sur-

gery. Patients meeting either of the first two exclusion criteria were, according to the trial design, excluded without consultation of the

local interventional cardiologist and cardiac surgeon. The need for concomitant surgery was discussed with the local interventional car-

diologist and cardiac surgeon. Data for patients who were assigned to one treatment but underwent the other and for those who did

AUTHOR: Serruys RETAKE 1st

not undergo either revascularization procedure ICMwere analyzed in an intention-to-treat manner. CABG denotes coronary-artery bypass

2nd

REG F FIGURE: 1 of 3

grafting, and PCI percutaneous coronary intervention. 39p6 3rd

CASE Revised

EMail Line 4-C SIZE

ARTIST: ts H/T H/T

rates of two of the individual components

Enon of the 12-month rate

Combo of major adverse cardiac or cere-

primary outcome, stroke and myocardial infarc- AUTHOR, brovascular events

PLEASE NOTE: between the two groups was

tion, were similar in the two groups (Table 2 in

Figure 5.5redrawn

has been percentage

and type points, with an upper 95% confi-

has been reset.

Please check carefully.

the Supplementary Appendix). At 12 months, the dence interval of 8.3 percentage points. The results

incidence of major adverse cardiac orJOB:

cerebrovas-

36010 of an as-treated analysisISSUE:were similar: the 12-month

03-05-09

cular events was lower in the CABG group (12.4%) rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular

than in the PCI group (17.8%, P = 0.002) (Fig. 2 events was 12.3% with CABG and 17.6% with PCI

and Table 3). Thus, the absolute difference in the (P = 0.002).

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 965

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Patients, According to Study Group.*

Characteristic PCI (N = 903) CABG (N = 897) P Value

Age — yr 65.2±9.7 65.0±9.8 0.55

Male sex — % 76.4 78.9 0.20

Body-mass index† 28.1±4.8 27.9±4.5 0.37

Medically treated diabetes — %‡

Any 25.6 24.6 0.64

Requiring insulin 9.9 10.4 0.72

Metabolic syndrome — % 46.0 45.5 0.86

Current smoker — % 18.5 22.0 0.06

Previous myocardial infarction — % 31.9 33.8 0.39

Previous stroke — % 3.9 4.8 0.33

Previous transient ischemic attack — % 4.3 5.1 0.46

Blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg — % 68.9 64.0 0.03

Congestive heart failure — % 4.0 5.3 0.18

Carotid artery disease — % 8.1 8.4 0.83

Hyperlipidemia — % 78.7 77.2 0.44

Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl (1.7 mmol/liter) — % 32.3 38.7 0.007

HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl (1.0 mmol/liter) 46.2 52.5 0.01

for men or <50 mg/dl (1.3 mmol/liter) for

women — %

Angina — %

Stable 56.9 57.2 0.91

Unstable 28.9 28.0 0.66

Ejection fraction <30% — % 1.3 2.5 0.08

euroSCORE value 3.8±2.6 3.8±2.7 0.78

Parsonnet score 8.5±7.0 8.4±6.8 0.76

SYNTAX score 28.4±11.5 29.1±11.4 0.19

No. of lesions 4.3±1.8 4.4±1.8 0.44

Total occlusion — % 24.2 22.2 0.33

Bifurcation — % 72.4 73.3 0.67

Time to procedure — days 6.9±13.0 17.4±28.0 <0.001

Procedure duration — hr 1.7±0.9 3.4±1.1 <0.001

Postprocedural hospital stay — days 3.4±4.5 9.5±8.0 <0.001

Complete revascularization — % 56.7 63.2 0.005

* Plus–minus values are means ±SD. Data are given for the intention-to-treat population. P values, the average SYNTAX

score, the average number of lesions, and the percentages of patients with total occlusion and bifurcation were calcu-

lated at the core laboratory. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (euroSCORE) value could

range from 0 to 18, with increasing values reflecting a higher predicted operative mortality.31 The Parsonnet score

could range from 0 to 47, with increasing values reflecting a higher predicted in-hospital mortality.32 The SYNTAX score

reflects a comprehensive anatomical assessment, with scores ranging from 0 to 83 and higher scores indicating more

complex coronary disease (see the Supplementary Appendix for details). CABG denotes coronary-artery bypass grafting,

HDL high-density lipoprotein, and PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

† The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

‡ Medically treated diabetes was defined as diabetes for which the patient was receiving oral hypoglycemic agents or in-

sulin at the time of enrollment.

966 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

In the intention-to-treat population, 19 patients

Table 2. Cardiac-Related Medications Given after the Study Procedure.*

would need to be treated with CABG to avoid the

primary outcome in 1 patient; the numbers needed Medication PCI CABG P Value

to treat to avoid specific components of the out- percent

come were 14 for revascularization, 119 for death, Any 98.9 98.6 0.62

and 71 for myocardial infarction. The number Aspirin

needed to treat with PCI to avoid stroke in 1 pa-

At discharge 96.3 88.5 <0.001

tient was 60.

1 Mo after procedure 93.5 85.4 <0.001

Secondary Outcome 6 Mo after randomization 93.2 82.7 <0.001

The rate of repeat revascularization at 12 months 12 Mo after randomization 91.2 84.3 <0.001

was significantly higher among patients in the Thienopyridine

PCI group than among those in the CABG group At discharge 96.8 19.5 <0.001

(13.5% vs. 5.9%, P<0.001) (Table 3). Most patients

1 Mo after procedure 95.5 18.4 <0.001

who underwent repeat revascularization were treat-

6 Mo after randomization 91.3 16.1 <0.001

ed with PCI rather than CABG. The rate of stroke

was significantly higher with CABG than with PCI 12 Mo after randomization 71.1 15.0 <0.001

at 12 months, even though the two groups were Any antiplatelet drug

well balanced with regard to carotid artery dis- At discharge 97.0 23.7 <0.001

ease and other risk factors for stroke (Table 3). At 1 Mo after procedure 95.8 21.2 <0.001

12 months, the two groups had similar rates of 6 Mo after randomization 91.4 18.4 <0.001

death from any cause or myocardial infarction

12 Mo after randomization 72.8 17.2 <0.001

and of the combined end point of death from any

cause, stroke, or myocardial infarction (Table 3). Nonthienopyridine antiplatelet drug 1.9 4.8 <0.001

The rate of death from cardiac causes was greater Warfarin derivative 2.6 7.1 <0.001

with PCI than with CABG (3.7% vs. 2.1%, P = 0.05); Statin 86.7 74.5 <0.001

the rate of death from noncardiac causes, although Beta-blocker 81.3 78.6 0.17

not significant, was higher with CABG (1.4% vs. ACE inhibitor 55.1 44.6 <0.001

0.7%, P = 0.13). The 12-month rates of symptom-

Calcium-channel blocker 25.8 18.4 <0.001

atic, angiographically confirmed graft occlusion

Angiotensin II–receptor antagonist 13.3 7.0 <0.001

(in the CABG group) and stent thrombosis (in the

PCI group) were similar (P = 0.89) (Table 3). Amiodarone 1.5 12.8 <0.001

H2-receptor blocker 14.5 21.7 <0.001

Outcomes According to the SYNTAX Score

* Percentages are from the intention-to-treat analysis. ACE denotes angiotensin-

In the CABG group, the binary 12-month rates of converting enzyme, CABG coronary-artery bypass grafting, and PCI percutane-

major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events ous coronary intervention.

were similar among patients with low SYNTAX

scores (0 to 22, 14.7%), those with intermediate

scores (23 to 32, 12.0%), and those with high scores events, whereas among patients with high scores,

(≥33, 10.9%) (Fig. 3). In contrast, in the PCI group, the event rate was significantly increased in the

the rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascu- PCI group (Fig. 3).

lar events was significantly increased among pa-

tients with high SYNTAX scores (23.4%) as com- Outcomes in Subgroups

pared with those with low scores (13.6%) or The subgroups of patients with left main or three-

intermediate scores (16.7%) (P = 0.002 for high vs. vessel coronary artery disease were prespecified,

low scores; P = 0.04 for high vs. intermediate scores) and the study had a statistical power of 80% for

(Fig. 3). There was a significant interaction be- each subgroup. However, the overarching statis-

tween SYNTAX score and treatment group (P = 0.01); tical test was a noninferiority assessment of data

patients with low or intermediate scores in the from all patients with either left main coronary

CABG group and in the PCI group had similar artery disease or three-vessel coronary disease (or

rates of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular both). Since noninferiority was not proven in this

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 967

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

A Death from Any Cause B Death from Any Cause, Stroke, or MI

20 20

P=0.37 P=0.99

Cumulative Rate (%)

Cumulative Rate (%)

10 10 7.7

PCI

4.4

PCI CABG 7.6

CABG 3.5

0 0

0 6 12 0 6 12

Months since Randomization Months since Randomization

C Repeat Revascularization D Major Adverse Cardiac or Cerebrovascular Event

17.8

20 20

P<0.001 P=0.002 PCI

Cumulative Rate (%)

Cumulative Rate (%)

13.5

PCI

10 10 CABG

CABG 12.4

5.9

0 0

0 6 12 0 6 12

Months since Randomization Months since Randomization

Figure 2. Rates of Outcomes among the Study Patients, According to Treatment Group.

AUTHOR: Serruys RETAKE 1st

Kaplan–Meier curves are shown forICM the percutaneous

FIGURE: 2 of 3

coronary intervention (PCI) group 2nd and the coronary-artery by-

REG F

pass grafting (CABG) group for death from any cause (Panel A); death, stroke, or myocardial

3rd infarction (MI) (Panel

B); repeat revascularization (PanelCASE

C); and the composite primary end point Revised

of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovas-

Line 4-C

EMail had similar rates of death from any cause SIZE(relative risk with PCI vs. CABG,

cular events (Panel D). The two groups ARTIST: ts H/T H/T 33p9

1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], Enon

0.78 to 1.98) and rates of death from any cause,

Combo stroke, or MI (relative risk with

PCI vs. CABG, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.38). In contrast,

AUTHOR, thePLEASE

rate ofNOTE:

repeat revascularization was significantly in-

creased with PCI (relative risk, 2.29; 95% CI,has

Figure 1.67 to redrawn

been 3.14), asand

was thehas

type overall rate of major adverse cardiac or cere-

been reset.

brovascular events (relative risk, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.15Please checkThe

to 1.81). carefully.

I bars indicate 1.5 SE. Relative risks were calculated

from the binary rates. P values were calculated with the use of the chi-square test.

JOB: 36010 ISSUE: 03-05-09

cohort, specific information for each subgroup is among those who also had two- or three-vessel

of an observational nature and is hypothesis gen- disease than among those with left main coro-

erating. The 12-month rate of major adverse car- nary artery disease alone or in combination with

diac or cerebrovascular events among patients with one-vessel disease (Fig. 6 in the Supplementary Ap-

left main coronary artery disease was similar in pendix).

the CABG and PCI groups (13.7% and 15.8%, The 12-month rate of major adverse cardiac or

respectively; P = 0.44). Although the rate of repeat cerebrovascular events among patients with three-

revascularization among patients with left main vessel disease in the absence of left main coronary

coronary artery disease was significantly higher artery disease was significantly increased in the

in the PCI group (11.8%, vs. 6.5% in the CABG PCI group as compared with the CABG group

group; P = 0.02), this result was offset by a signifi- (19.2% vs. 11.5%, P<0.001) (Fig. 6 in the Supple-

cantly higher rate of stroke in the CABG sub- mentary Appendix), as was the rate of repeat revas-

group of patients with left main coronary artery cularization (14.6% vs. 5.5%, P<0.001). The rate

disease (2.7%, vs. 0.3% in the corresponding PCI of death from any cause, stroke, or myocardial

subgroup; P = 0.01). A total of 36.6% of patients infarction in this subgroup was similar with PCI

with left main coronary artery disease also had and CABG (8.0% and 6.6%, respectively; P = 0.39).

three-vessel disease. A post hoc analysis of the Comparisons of data for the cohort with left

rates of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular main coronary artery disease and the cohort with

events in the subgroups of patients with left main three-vessel disease showed that the cohort with

coronary artery disease revealed a higher rate three-vessel disease had higher rates of previous

968 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

Table 3. Clinical End Points Occurring in the Hospital or after Discharge, According to Study Group.*

Relative Risk with

Variable PCI CABG P Value PCI (95% CI)

no./total no. (%)

Major adverse cardiac or

cerebrovascular event

In hospital 39/896 (4.4) 47/870 (5.4) 0.31 0.81 (0.53–1.22)

30 Days after procedure 54/895 (6.0) 45/866 (5.2) 0.45 1.16 (0.79–1.71)

6 Mo after randomization 111/893 (12.4) 85/860 (9.9) 0.09 1.26 (0.96–1.64)

12 Mo after randomization 159/891 (17.8) 105/849 (12.4) 0.002 1.44 (1.15–1.81)

Death, stroke, or MI 68/891 (7.6) 65/849 (7.7) 0.98 1.00 (0.72–1.38)

Death 39/891 (4.4) 30/849 (3.5) 0.37 1.24 (0.78–1.98)

From cardiac causes 33/891 (3.7) 18/849 (2.1) 0.05 1.75 (0.99–3.08)

From cardiovascular causes 1/891 (0.1) 3/849 (0.4) 0.36† 0.32 (0.03–3.05)

From noncardiovascular causes 5/891 (0.6) 9/849 (1.1) 0.24 0.53 (0.18–1.57)

Stroke 5/891 (0.6) 19/849 (2.2) 0.003 0.25 (0.09–0.67)

MI 43/891 (4.8) 28/849 (3.3) 0.11 1.46 (0.92–2.33)

Repeat revascularization‡ 120/891 (13.5) 50/849 (5.9) <0.001 2.29 (1.67–3.14)

CABG 25/891 (2.8) 11/849 (1.3) 0.03 2.17 (1.07–4.37)

PCI 102/891 (11.4) 40/849 (4.7) <0.001 2.43 (1.71–3.46)

Graft occlusion or stent thrombosis§ 28/848 (3.3) 27/784 (3.4) 0.89 0.96 (0.57–1.62)

Acute (at ≤1 day) 2/896 (0.2) 3/870 (0.3) 0.68† 0.65 (0.11–3.86)

Early (within 2–30 days) 18/893 (2.0) 3/868 (0.3) 0.001 5.83 (1.72–19.73)

Late (within 31–365 days) 9/874 (1.0) 21/854 (2.5) 0.02 0.42 (0.19–0.91)

* Percentages are from the intention-to-treat analysis. P values were calculated with the use of the chi-square test, unless

otherwise noted. CABG denotes coronary-artery bypass grafting, MI myocardial infarction, and PCI percutaneous coro-

nary intervention.

† The P value was calculated with the use of Fisher’s exact test.

‡ One patient randomly assigned to undergo CABG and seven patients randomly assigned to undergo PCI underwent

both repeat PCI and repeat CABG.

§ Stent thrombosis and graft occlusion were adjudicated according to confirmation in symptomatic patients.

myocardial infarction, diabetes, poor left ventricu- ings with regard to components of the primary end

lar ejection fraction, and lesions with adverse char- point and subgroup analyses can only be consid-

acteristics (lesions that were totally occluded, bi- ered as hypothesis-generating. Rates of death and

furcated, or long). In addition, the cohort with myocardial infarction at 1 year were similar be-

three-vessel disease had increased numbers of tween patients who underwent CABG and those

treated vessels and lesions per patient. who underwent PCI with drug-eluting stents,

whereas the rate of stroke was increased in the

Discussion CABG group and the rate of repeat revasculariza-

tion was increased in the PCI group.

The SYNTAX trial was designed to compare cur- Rates of repeat revascularization at 12 months

rent surgical and percutaneous techniques in pa- were low in the PCI group, given the high rates

tients with three-vessel or left main coronary ar- of several known predictors of restenosis: lesions

tery disease (or both). For the primary end point, characterized by bifurcation or trifurcation (>80%),

the 12-month rate of major adverse cardiac or cere- multivessel disease (>60%), diabetes (>25%), and

brovascular events, the noninferiority of PCI as lesions that were long (>20 mm in length, 20%)

compared with CABG was not demonstrated; or totally occluded (>25%). This rate of repeat

CABG proved to be superior. Therefore, the find- revascularization is lower than the rates reported

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 969

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

to be balanced against the invasiveness of CABG

A Low SYNTAX Score

Cumulative Rate of Major

and the risk of stroke, as previously reported in

Cerebrovascular Events 30

P=0.71 a meta-analysis of 23 studies comparing CABG

Adverse Cardiac or

and PCI, in which procedure-related strokes were

20 14.7 found to be more common after CABG (in 1.2%

(%)

CABG

of patients, vs. 0.6% of those undergoing PCI;

10

PCI 13.6 P<0.001), without a concomitant decrease in sur-

vival.34

0

0 6 12 Recently, concern has been expressed about the

Months since Randomization possibility of an increased risk of late stent throm-

bosis with drug-eluting stents. In the SYNTAX trial,

B Intermediate SYNTAX Score most cases of stent thrombosis occurred within

30 days after the procedure, and the 12-month rate

Cumulative Rate of Major

30

Cerebrovascular Events

P=0.10

of stent thrombosis in the PCI group was similar

Adverse Cardiac or

16.7

20 PCI to the rate of symptomatic graft occlusion in the

CABG group. However, as described in the litera-

(%)

10 CABG ture, stent thrombosis often has more serious

12.0

consequences for patients (rate of death, ap-

0 proximately 30%; rate of myocardial infarction,

0 6 12

>60%)35,36 than does graft occlusion, which often

Months since Randomization

results only in angina leading to revascularization.

C High SYNTAX Score The use of antiplatelet medication was high

among patients in the PCI group (with 71.1%

Cumulative Rate of Major

30 23.4

Cerebrovascular Events

P<0.001 receiving a thienopyridine at 12 months). There

Adverse Cardiac or

PCI

20

was an imbalance between the two groups with

regard to general medical management apart from

(%)

10 thienopyridine use. Thienopyridine therapy was

CABG

10.9 not mandated beyond 6 months in the PCI group,

0 since the study was designed to compare current

0 6 12 CABG and PCI practices, including medication

Months since Randomization regimens. The low rate of stroke among patients

Figure 3. Rates of Major Adverse Cardiac or Cerebrovascular Events

who underwent PCI may have resulted from the

among the Study AUTHOR: Serruys RETAKE

ICM Patients, According to Treatment Group and SYNTAX

1st use of highly effective dual-antiplatelet therapy,

Score Category.REG F FIGURE: 3 of 3 2nd which prevents thromboembolic events; additional

3rd

Kaplan–MeierCASEcurves are shown for the percutaneous Revisedcoronary intervention treatment with antiplatelet drugs might there-

4-C (CABG)

Line grafting

(PCI) group and the coronary-artery bypass

ARTIST: ts

SIZEgroup for ma- fore benefit patients undergoing CABG. In addi-

jor adverse cardiac H/T H/T

Enon or cerebrovascular events at 12 months. 22p3The 12-month tion, more patients in the CABG group than in

Combo

event rates were similar between the two treatment groups for patients

with low SYNTAXFigurescoreshas AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:

(0been

to 22) (Panel A) or intermediate SYNTAX

the PCI group declined to participate after pro-

redrawn and type has been reset. viding consent; in general, this imbalance was due

scores (23 to 32) (Panel B). Among patients

Please check with high SYNTAX scores

carefully.

(≥33, indicating the most complex disease), those in the PCI group had a to the greater invasiveness of CABG.

significantlyJOB:

higher event rate at 12 months than those

36010 ISSUE:in03-05-09

the CABG group. The SYNTAX score was designed to predict out-

SYNTAX scores were calculated at the core laboratory. The I bars indicate comes related to anatomical characteristics and,

1.5 SE. P values were calculated with the use of the chi-square test.

to a lesser extent, the functional risk of occlusion

for any segment of the coronary-artery bed (as re-

in previous comparative trials involving patients flected by the Leaman score37). In our study, the

with less-complex clinical profiles and lesions.10 raw SYNTAX score was predictive of outcomes in

The increase in the rate of repeat revasculariza- patients who underwent PCI. In particular, among

tion with PCI as compared with CABG did not patients in the PCI group with high SYNTAX

appear to translate into a significant overall in- scores, not only was the overall rate of major ad-

crease in the rate of death or myocardial infarc- verse cardiac or cerebrovascular events signifi-

tion, although longer-term follow-up is needed. cantly increased, but also the rate of the compos-

The risk of repeat revascularization after PCI needs ite components of death, stroke, and myocardial

970 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

infarction was slightly raised (11.9%, vs. 7.6% in meta-analysis did not show any significant differ-

the CABG group; P = 0.08). This finding suggests ences in rates of survival between the CABG and

that a percutaneous approach should be avoided PCI groups,34 although other studies have shown

in patients with high SYNTAX scores. Similar differences in mortality.10-12

results were reported after the stratification of Second, the use of medication differed between

patients with three-vessel disease in the ARTS II the groups in our study, reflecting variations in

registry.38 Retrospective analysis of the ability of standard care of patients between the two treat-

the SYNTAX score to predict outcome is currently ment groups. Third, more patients withdrew, af-

being performed and is anticipated to be used to ter randomization, from the CABG group than

evaluate the relative weight of the individual score from the PCI group. Fourth, although random-

components. Additional validation of the score in ization was conducted in a blinded manner, with

other populations of patients is also needed. Out- clinicians and participants unaware of future

comes in the surgical group of our randomized treatment assignments, it was not possible to blind

cohort were not influenced by the SYNTAX score. the performance of the treatment. Finally, the

The completeness of revascularization (i.e., definition of myocardial infarction was based on

whether all identified lesions were treated) was a surgical definition (the finding of a new Q-wave

determined after the procedure by the investiga- on electrocardiography, in association with a value

tor. The rate of complete revascularization was for the creatine kinase MB fraction that was five

lower in both treatment groups in our study than times the upper limit of the normal range), which Clinical Directions:

in previous studies.14,15,21,23,39 This result is most may have resulted in less severe cases of myocar- Vote and comment

on this article and

likely due to a different definition of completeness dial infarction being overlooked. view the video

of treatment used in the earlier trials and the more In conclusion, the results of our trial show that roundtable at

complex anatomical characteristics of the patients CABG, as compared with PCI, is associated with NEJM.org

in our trial. a lower rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebro-

Although our study provides important infor- vascular events at 1 year among patients with

mation about current treatment of coronary artery three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease

disease, there are limitations. First, the 12-month (or both) and should therefore remain the stan-

follow-up period may not be sufficient to reflect dard of care for such patients.

the true long-term effect of CABG as compared Supported by Boston Scientific.

Dr. Kappetein reports receiving consulting and lecture fees

with PCI with drug-eluting stents on cardiac-relat- from Boston Scientific; and Dr. Feldman, consulting and lecture

ed health. However, our early results in terms of fees and grant support from Boston Scientific and consulting

major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events fees from Abbott. Mr. Bass and Mr. Van Dyck and Drs. Leadley

and Dawkins report being full-time employees of, and owning

are similar to those of a meta-analysis34 of trials equity in, Boston Scientific. No other potential conflict of inter-

comparing CABG and PCI with predominantly est relevant to this article was reported.

bare-metal stents. The meta-analysis showed that We thank the clinical events committee (V.L. Babikian, D.

Birnbaum, T.P. Carrel, M. Gorman, C. Hanet, O.M. Hess,

the rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovas- E.W.L. Jansen, L.J. Kappelle, P.G. Steg) and the data and safety

cular events was lower with CABG than with PCI monitoring committee (J.-P. Bassand, T. Clayton, D.P. Faxon,

and that patients who underwent CABG had fewer B.J. Gersh, J.L. Monro, S. Pocock, M.I. Turina) of the SYNTAX

trial, Kristine Roy of Boston Scientific for her help in prepar-

repeat revascularization procedures than patients ing the manuscript, and Peggy Pereda of Boston Scientific for

who underwent PCI. After 5 years of follow-up, the her help with data analysis.

References

1. Favaloro RG. Saphenous vein autograft 4. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, onary atherosclerosis. Ann Thorac Surg

replacement of severe segmental coronary Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of 2008;85:1473-82.

artery occlusion: operative technique. Ann prolonged stay in the intensive care unit 7. Grüntzig A. Transluminal dilatation

Thorac Surg 1968;5:334-9. for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardio- of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet 1978;1:

2. Buxton BF, Komeda M, Fuller JA, Gor- thorac Surg 2004;25:203-7. 263.

don I. Bilateral internal thoracic artery 5. Tavilla G, Kappetein AP, Braun J, 8. Bittl JA. Advances in coronary angio-

grafting may improve outcome of coronary Gopie J, Tjien AT, Dion RA. Long-term plasty. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1290-302.

artery surgery: risk-adjusted survival. Cir- follow-up of coronary artery bypass graft- [Erratum, N Engl J Med 1997;336:670.]

culation 1998;98:Suppl:II-1–II-6. ing in three-vessel disease using exclu- 9. Serruys PW, Kutryk MJB, Ong ATL.

3. Flynn M, Reddy S, Shepherd W, et al. sively pedicled bilateral internal thoracic Coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med 2006;

Fast-tracking revisited: routine cardiac sur- and right gastroepiploic arteries. Ann Tho- 354:483-95.

gical patients need minimal intensive care. rac Surg 2004;77:794-9. 10. Booth J, Clayton T, Pepper J, et al.

Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;25:116-22. 6. Barner HB. Operative treatment of cor- Randomized, controlled trial of coronary

n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009 971

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PCI vs. CABG for Severe Coronary Artery Disease

artery bypass surgery versus percutane- et al. A comparison between coronary ar- to Review New Evidence and Update the

ous coronary intervention in patients with tery bypass grafting surgery and drug ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for

multivessel coronary artery disease: six- eluting stent for the treatment of unpro- Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Writ-

year follow-up from the Stent or Surgery tected left main coronary artery disease in ing on Behalf of the 2005 Writing Commit-

Trial (SoS). Circulation 2008;118:381-8. elderly patients (aged > or =75 years). Eur tee. Circulation 2008;117:261-95. [Erratum,

11. Daemen J, Boersma E, Flather M, et al. Heart J 2007;28:2714-9. Circulation 2008;117(6):e161.]

Long-term safety and efficacy of percuta- 22. Sanmartin M, Baz JA, Claro R, et al. 31. Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gaud-

neous coronary intervention with stenting Comparison of drug-eluting stents versus ucheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. Euro-

and coronary artery bypass surgery for surgery for unprotected left main coro- pean System for Cardiac Operative Risk

multivessel coronary artery disease: a meta- nary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2007; Evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardiotho-

analysis with 5-year patient-level data from 100:970-3. rac Surg 1999;16:9-13.

the ARTS, ERACI-II, MASS-II, and SoS tri- 23. Yang ZK, Shen WF, Zhang RY, et al. 32. Parsonnet V, Dean D, Bernstein AD.

als. Circulation 2008;118:1146-54. Coronary artery bypass surgery versus A method of uniform stratification of risk

12. Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G, et al. percutaneous coronary intervention with for evaluating the results of surgery in ac-

Drug-eluting stents vs. coronary-artery by- drug-eluting stent implantation in patients quired adult heart disease. Circulation

pass grafting in multivessel coronary dis- with multivessel coronary disease. J Interv 1989;79:I-3–I-12. [Erratum, Circulation

ease. N Engl J Med 2008;358:331-41. Cardiol 2007;20:10-6. 1990;82:1078.]

13. Brener SJ, Galla JM, Bryant R III, Sabik 24. Serruys PW, Daemen J, Morice M-C, et 33. Expert Panel on Detection, Evalua-

JF III, Ellis SG. Comparison of percutane- al. Three-year follow-up of the ARTS-II– tion, and Treatment of High Blood Cho-

ous versus surgical revascularization of sirolimus-eluting stents for the treatment lesterol in Adults. Executive summary of

severe unprotected left main coronary of patients with multivessel coronary ar- the Third Report of the National Choles-

stenosis in matched patients. Am J Car- tery disease. EuroIntervention 2007;3: terol Education Program (NCEP) Expert

diol 2008;101:169-72. 450-9. Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treat-

14. Briguori C, Condorelli G, Airoldi F, 25. Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, et ment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults

et al. Comparison of coronary drug-elut- al. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;

ing stents versus coronary artery bypass and bare-metal stents: a collaborative net- 285:2486-97.

grafting in patients with diabetes mellitus. work meta-analysis. Lancet 2007;370:937- 34. Bravata DM, Gienger AL, McDonald

Am J Cardiol 2007;99:779-84. 48. KM, et al. Systematic review: the compara-

15. Buszman PE, Kiesz SR, Bochenek A, 26. Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld tive effectiveness of percutaneous coro-

et al. Acute and late outcomes of unpro- JW Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guide- nary interventions and coronary artery by-

tected left main stenting in comparison line update for percutaneous coronary in- pass graft surgery. Ann Intern Med 2007;

with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll tervention: a report of the American College 147:703-16.

Cardiol 2008;51:538-45. of Cardiology/American Heart Association 35. Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K,

16. Chieffo A, Morici N, Maisano F, et al. Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/ et al. Early and late coronary stent throm-

Percutaneous treatment with drug-eluting AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update bosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-

stent implantation versus bypass surgery the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Cor- eluting stents in routine clinical practice:

for unprotected left main stenosis: a sin- onary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; data from a large two-institutional cohort

gle-center experience. Circulation 2006;113: 47(1):e1-e121. study. Lancet 2007;369:667-78.

2542-7. 27. Kappetein AP, Dawkins KD, Mohr 36. Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Ho

17. Herz I, Moshkovitz Y, Loberman D, et FW, et al. Current percutaneous coronary KK, D’Agostino R, Cutlip DE. Stent throm-

al. Drug-eluting stents versus bilateral in- intervention and coronary artery bypass bosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-

ternal thoracic grafting for multivessel grafting practices for three-vessel and left eluting stents. N Engl J Med 2007;356:

coronary disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; main coronary artery disease: insights 1020-9.

80:2086-90. from the SYNTAX run-in phase. Eur J Car- 37. Leaman DM, Brower RW, Meester GT,

18. Javaid A, Steinberg DH, Buch AN, et al. diothorac Surg 2006;29:486-91. Serruys P, van den Brand M. Coronary ar-

Outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft- 28. Ong AT, Serruys PW, Mohr FW, et al. tery atherosclerosis: severity of the disease,

ing versus percutaneous coronary interven- The SYNergy between percutaneous coro- severity of angina pectoris and compro-

tion with drug-eluting stents for patients nary intervention with TAXus and cardiac mised left ventricular function. Circula-

with multivessel coronary artery disease. surgery (SYNTAX) study: design, rationale, tion 1981;63:285-99.

Circulation 2007;116:Suppl:I-200–I-206. and run-in phase. Am Heart J 2006;151: 38. Valgimigli M, Serruys PW, Tsuchida K,

19. Lee MS, Jamal F, Kedia G, et al. Com- 1194-204. et al. Cyphering the complexity of coronary

parison of bypass surgery with drug-elut- 29. Sianos G, Morel MA, Kappetein AP, et artery disease using the Syntax score to

ing stents for diabetic patients with mul- al. The SYNTAX score: an angiographic tool predict clinical outcome in patients with

tivessel disease. Int J Cardiol 2007;123: grading the complexity of coronary artery three-vessel lumen obstruction undergo-

34-42. disease. EuroIntervention 2005;1:219-27. ing percutaneous coronary intervention.

20. Lee MS, Kapoor N, Jamal F, et al. 30. King SB III, Smith SC Jr, Hirshfeld JW Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1072-81.

Comparison of coronary artery bypass Jr, et al. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/ 39. van den Brand MJBM, Rensing BJWM,

surgery with percutaneous coronary in- AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Per- Morel MM, et al. The effect of complete-

tervention with drug-eluting stents for cutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report ness of revascularization on event-free sur-

unprotected left main coronary artery dis- of the American College of Cardiology/ vival at one year in the ARTS trial. J Am

ease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:864-70. American Heart Association Task Force on Coll Cardiol 2002;39:559-64.

21. Palmerini T, Barlocco F, Santarelli A, Practice Guidelines: 2007 Writing Group Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society.

972 n engl j med 360;10 nejm.org march 5, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Acute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyFrom EverandAcute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyEdgar A. SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- Pender Novant LOI ReleaseDocument2 pagesPender Novant LOI ReleaseBen SchachtmanNo ratings yet

- Madit CRTNEJMseot 09Document10 pagesMadit CRTNEJMseot 09binh doNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2206606Document10 pagesNejmoa 2206606dipan diratuNo ratings yet

- Catheter Ablationin in AF With CHFDocument11 pagesCatheter Ablationin in AF With CHFKristian Sudana HartantoNo ratings yet

- Heartfailure FixDocument10 pagesHeartfailure FixdhikaNo ratings yet

- Ezt 017Document8 pagesEzt 017Abhilash VemulaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Optimal Medical Therapy On 10-Year Mortality After Coronary RevascularizationDocument12 pagesImpact of Optimal Medical Therapy On 10-Year Mortality After Coronary RevascularizationsarahNo ratings yet

- 10 1056@NEJMoa1909406Document11 pages10 1056@NEJMoa1909406alvaroNo ratings yet

- Tonino 2009Document12 pagesTonino 2009Paul CalbureanNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0007091217540015Document10 pagesPi Is 0007091217540015Yoga WibowoNo ratings yet

- PCI StrategyDocument14 pagesPCI StrategyJason WinathaNo ratings yet

- Castle AfDocument11 pagesCastle AfgustavoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0735109719300956 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0735109719300956 MainAlberto PolimeniNo ratings yet

- Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel in Patients With Acute Coronary SyndromesDocument15 pagesPrasugrel Versus Clopidogrel in Patients With Acute Coronary SyndromesDito LopezNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty and Stenting As First-Choice Treatment in Patients With Chronic Mesenteric IschemiaDocument6 pagesPercutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty and Stenting As First-Choice Treatment in Patients With Chronic Mesenteric IschemiaCotaga IgorNo ratings yet

- Freedom TrialDocument10 pagesFreedom TrialJamalkabeerNo ratings yet

- Defibrilator in CardioDocument10 pagesDefibrilator in CardioNabila CpNo ratings yet

- CourageDocument14 pagesCourageSuryaNo ratings yet

- Ischemia CKD Trial - NEJM 2020Document11 pagesIschemia CKD Trial - NEJM 2020Vicken ZeitjianNo ratings yet

- Multivessel CADDocument4 pagesMultivessel CADJohn HetharieNo ratings yet

- Archivos - CT Angiography Followed by InvasiveDocument10 pagesArchivos - CT Angiography Followed by InvasiveGiselle LeonNo ratings yet

- Safety and Ef Ficacy of An Endovascular-First Approach To Acute Limb IschemiaDocument9 pagesSafety and Ef Ficacy of An Endovascular-First Approach To Acute Limb IschemiaSisca Dwi AgustinaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument11 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofahmadto80No ratings yet

- Sdauijknficskdla Jidalksnd JkcmaszDocument9 pagesSdauijknficskdla Jidalksnd Jkcmasz0395No ratings yet

- Focus 1 Paper 4 Verheye Et Al 2015Document9 pagesFocus 1 Paper 4 Verheye Et Al 2015Jesson LuiNo ratings yet

- Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion During Cadiac Surgery To Prevent StrokeDocument11 pagesLeft Atrial Appendage Occlusion During Cadiac Surgery To Prevent Strokengoc tin nguyenNo ratings yet

- Effects of Statins On Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaques The PARADIGM Study.Document10 pagesEffects of Statins On Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaques The PARADIGM Study.Oscar OrtegaNo ratings yet

- DAPTDocument12 pagesDAPTPedro JalladNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument9 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofHesbon MomanyiNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument13 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofAlexei Ricse JiménezNo ratings yet

- OCT Vs AngiographyDocument11 pagesOCT Vs Angiographytalal.fazmin1No ratings yet

- Cto Pci VS CabgDocument30 pagesCto Pci VS Cabgbayusetia150278No ratings yet

- Tutorial ElectrocardiogramaDocument6 pagesTutorial ElectrocardiogramakodagaNo ratings yet

- Angiography After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Without ST-Segment ElevationDocument10 pagesAngiography After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Without ST-Segment ElevationYuritza Patricia Vargas OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Manual Aspiration Thrombectomy in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Clinical ExperienceDocument9 pagesManual Aspiration Thrombectomy in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Clinical ExperienceArdiana FirdausNo ratings yet

- Complete Revascularization With Multivessel PCI For Myocardial InfarctionDocument11 pagesComplete Revascularization With Multivessel PCI For Myocardial InfarctionRicardo BarreraNo ratings yet

- Trial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesDocument13 pagesTrial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesMABEL LUCERO OLARTE JURADONo ratings yet

- PCI or CABG, That Is The Question!: Jong Shin Woo, MD, and Weon Kim, MDDocument2 pagesPCI or CABG, That Is The Question!: Jong Shin Woo, MD, and Weon Kim, MDHeńřÿ ŁøĵæńNo ratings yet

- Grace Steg2002Document6 pagesGrace Steg2002crsscribdNo ratings yet

- Atm 08 23 1626Document12 pagesAtm 08 23 1626Susana MalleaNo ratings yet

- Acs 33 241Document9 pagesAcs 33 241Ratna AyieNo ratings yet

- Randomized Trial of Primary PCI With or Without Routine Manual ThrombectomyDocument15 pagesRandomized Trial of Primary PCI With or Without Routine Manual ThrombectomyTony Santos'sNo ratings yet

- Biomarker-Based Risk Model To Predict Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients With Stable Coronary DiseaseDocument14 pagesBiomarker-Based Risk Model To Predict Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients With Stable Coronary Diseasejenny puentesNo ratings yet

- En Do Vascular Stenting or Carotid My For Treatment of Carotid Stenosis A Meta AnalysisDocument6 pagesEn Do Vascular Stenting or Carotid My For Treatment of Carotid Stenosis A Meta Analysisjohn_smith_532No ratings yet

- Ok Fame - II - NEJM - 2012Document11 pagesOk Fame - II - NEJM - 2012Christian OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Stable Chest Pain - An Evolving Approach: EditorialDocument2 pagesEvaluating Stable Chest Pain - An Evolving Approach: EditorialMahmoud AbouelsoudNo ratings yet

- BestDocument9 pagesBestDina sofianaNo ratings yet

- Endovascular Stentgraft Placement in Aortic Dissection A MetaanalysisDocument10 pagesEndovascular Stentgraft Placement in Aortic Dissection A MetaanalysisCiubuc AndrianNo ratings yet

- Cetin 2016Document10 pagesCetin 2016Della Puspita SariNo ratings yet

- Sardar 2017Document10 pagesSardar 2017hafizaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Coronary In-Stent Restenosis With A Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon CatheterDocument12 pagesTreatment of Coronary In-Stent Restenosis With A Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon CatheterReza Ishak EstikoNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument11 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofCyntia AndrinaNo ratings yet

- Short - and Long-Term Outcomes at A Single InstitutionDocument7 pagesShort - and Long-Term Outcomes at A Single InstitutionJonathan Frimpong AnsahNo ratings yet

- Cartlidge Timothy Role of Percutaneous CoronaryDocument7 pagesCartlidge Timothy Role of Percutaneous Coronarybruno baileyNo ratings yet

- Poise-3 (Nejm 2022)Document12 pagesPoise-3 (Nejm 2022)Jesus MujicaNo ratings yet

- 02art8090web PDFDocument9 pages02art8090web PDFSyilla PriscilliaNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa1608029 PDFDocument10 pagesNejmoa1608029 PDFFhirastika AnnishaNo ratings yet

- DES Vs CABGDocument11 pagesDES Vs CABGFurqan MirzaNo ratings yet

- Catheter Ablation in End Stage Heart FailureDocument10 pagesCatheter Ablation in End Stage Heart FailureJose Gomez MorenoNo ratings yet

- 10 1159@000510402Document8 pages10 1159@000510402Guillermo Chacon AcevedoNo ratings yet

- 23 - Preoperative Patient Assessment and ManagementDocument1 page23 - Preoperative Patient Assessment and ManagementHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- 2018 Multimodal General Anesthesia BrownDocument13 pages2018 Multimodal General Anesthesia BrownMayritaSolizSossaNo ratings yet

- Omori, 2004Document4 pagesOmori, 2004Henrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Caudal Epidural Blocks in Pediatrics - withMarginNotesDocument1 pageCaudal Epidural Blocks in Pediatrics - withMarginNotesHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- 5 - Hung, 2004Document4 pages5 - Hung, 2004Henrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Karger, 2004Document3 pagesKarger, 2004Henrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Hiorns, 2004Document3 pagesHiorns, 2004Henrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Técnicas de EstudioDocument55 pagesTécnicas de EstudiojrdelarosaNo ratings yet

- Civd - AjcpDocument11 pagesCivd - AjcpHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Hepatic Rupture Caused by Peliosis HepatisDocument4 pagesHepatic Rupture Caused by Peliosis HepatisHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Experimental Phage Therapy Against Lethal Lung-Derived Septicemia Caused by Staphylococcus Aureus in MiceDocument6 pagesExperimental Phage Therapy Against Lethal Lung-Derived Septicemia Caused by Staphylococcus Aureus in MiceHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- What Is Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting - NHLBI, NIHDocument1 pageWhat Is Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting - NHLBI, NIHHenrique MachadoNo ratings yet

- Key Performance Indicators (Kpis) For Healthcare Accreditation SystemDocument18 pagesKey Performance Indicators (Kpis) For Healthcare Accreditation SystemNikeshKumarSinghNo ratings yet

- Step 3 Sample Questions 2015Document41 pagesStep 3 Sample Questions 2015yepherenow100% (2)

- CurosurDocument2 pagesCurosuredNo ratings yet

- Healing Garden ArchitectureDocument2 pagesHealing Garden Architecturedivyani dalalNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Gland: Pactical Activity No. 5Document19 pagesThyroid Gland: Pactical Activity No. 5Damian CorinaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart DiseasesDocument40 pagesCongenital Heart DiseasesiooaNo ratings yet

- Admission ProcedureDocument4 pagesAdmission ProcedureTrishna Das0% (1)

- Acute Brain InjuryDocument96 pagesAcute Brain InjuryManjiwan GarchaNo ratings yet

- Management of Poisoned PatientsDocument56 pagesManagement of Poisoned PatientsAmmarah TaimurNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Examination - OSCE SkillsDocument5 pagesAbdominal Examination - OSCE SkillsMastura IsmailNo ratings yet

- Painmaster Fact Sheet FRPDocument2 pagesPainmaster Fact Sheet FRPapi-11585491No ratings yet

- 103 3Document45 pages103 3Carolina Polo TorresNo ratings yet

- Personality Assessment: The InterviewDocument10 pagesPersonality Assessment: The InterviewgHiEmUeLNo ratings yet

- Cavity Design Line Angle and Point Angle: Presented ByDocument93 pagesCavity Design Line Angle and Point Angle: Presented ByANUBHA100% (1)

- VSD Guide: Types, Causes and Nursing Care for Ventricular Septal DefectDocument53 pagesVSD Guide: Types, Causes and Nursing Care for Ventricular Septal DefectAuni Akif AleesaNo ratings yet

- Aravind Eye Care HospitalDocument4 pagesAravind Eye Care HospitalEmma Litting0% (1)

- VAD Statewide Pharmacy Service VicTAG 15may2019Document54 pagesVAD Statewide Pharmacy Service VicTAG 15may2019Jonoffski “Mr Sopping Clam”No ratings yet

- Siatic NerveDocument33 pagesSiatic Nervenithin nairNo ratings yet

- States of Consciousness and Psychoactive DrugsDocument47 pagesStates of Consciousness and Psychoactive DrugsAdam WhiteNo ratings yet

- Understanding Fees in Mental Health PracticeDocument14 pagesUnderstanding Fees in Mental Health PracticeMateoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On Management of Postoperative Pain PDFDocument27 pagesGuidelines On Management of Postoperative Pain PDFMarcoNo ratings yet

- Pathology of the Central Nervous System: Neurodegenerative Diseases and CNS TumorsDocument67 pagesPathology of the Central Nervous System: Neurodegenerative Diseases and CNS TumorsLIEBERKHUNNo ratings yet

- The Devolution of The Philippine Health SystemDocument27 pagesThe Devolution of The Philippine Health SystemKizito Lubano100% (1)

- Cardiac Cirrhosis and Congestive HepatopathyDocument4 pagesCardiac Cirrhosis and Congestive HepatopathyAmelia AlresnaNo ratings yet

- MiniCollect Capillary Blood Collection System Brochure en Rev04 0321 WebDocument9 pagesMiniCollect Capillary Blood Collection System Brochure en Rev04 0321 Webbassam alharaziNo ratings yet

- Nasal Fracture Management and NOE Fracture TreatmentDocument17 pagesNasal Fracture Management and NOE Fracture TreatmentWahyu JuliandaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Work Conditioning and Work Hardening Programs For A Successful RTW 3-13-2014 NovaCareDocument37 pagesUnderstanding Work Conditioning and Work Hardening Programs For A Successful RTW 3-13-2014 NovaCareSitiSarahNo ratings yet

- Physical Examination Health AssessmentDocument2 pagesPhysical Examination Health AssessmentRosa Willis0% (1)

- Process Recording FormDocument12 pagesProcess Recording FormLaura Hernandez100% (1)