Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Checkpoint Time: Helga Tawil-Souri

Uploaded by

Vinícius PedreiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Checkpoint Time: Helga Tawil-Souri

Uploaded by

Vinícius PedreiraCopyright:

Available Formats

Checkpoint Time

helga tawil-souri

Under siege, life is time

Between remembering its beginning

And forgetting its end

The siege is waiting

Waiting on the tilted ladder in the middle of the storm

Mahmoud Darwish, State of Siege

the connections among beings alone make time

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern

Prologue: Spring Forward, Fall Back

It was my one chance to meet Yasser Arafat: a friend who worked

with Arafat called me out of the blue on a Friday morning in March

2003 and said to come by at 9 p.m.1 It struck me as odd to be invited

to the muqata’a at night, but I figured that having been imprisoned in

his compound for a year already, no doubt Arafat had a different

sense of time from those of us not locked up.

qui parle Vol. 26, No. 2, December 2017

doi 10.1215/10418385-4208442 © 2018 Editorial Board, Qui Parle

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

384 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

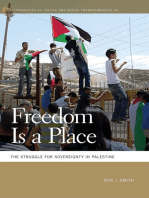

Fig. 1. Fences and walls, along the periphery of a checkpoint. Qalandia,

2015

I planned to arrive in Ramallah by 7. Traveling from ar-Ram to

Ramallah—a distance of five kilometers—I did not expect delay go-

ing “in” through the Qalandia checkpoint. I also planned to spend

the night at a friend’s, given it was not uncommon, especially at

night, for the checkpoint to be closed on the way “out.”2

I made my way up to the soldier. “Checkpoint closed,” he grum-

bled, without lifting his eyes. “Closed? Why?”

To have the whole checkpoint closed, and especially on the way

in, would have been likely if it had been a Jewish holiday, a European

diplomat was visiting the Israeli prime minister, the United States

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 385

was increasing its bombing campaign in Iraq, or some other far-off

event was taking place that the Israeli regime used as a pretext to en-

cumber Palestinians—none of which was the case that day.

Seeing that I hadn’t moved, the soldier barked, “It’s 7 o’clock.”

I was on my way to meet the president, so I had planned my travel

time carefully. I looked at my watch. “It’s 6,” I said.

“No. It’s 7.” I looked at my watch again. As I looked back up at

him, he grinned: “Daylight savings.” Yes, that strange modern inven-

tion of setting the clock forward.

“But daylight savings starts in two weeks,” I responded.

He retorted: “It is already daylight savings in Israel. It is 7.”3

“But we’re in the West Bank,” I said. The Green Line was a few

kilometers well to our west.

The corner of his lips took a slant upward, almost smiling. He

matter-of-factly declared: “Checkpoints are in Israel.”

I was standing in a no-man’s-land where it was 7 p.m., while in

some circumference beyond it was 6 p.m. I wondered where the

line was where I could have half of my body in one time zone and

the other half in another time zone. But I didn’t bother asking. In the

soldier’s logic, which had the backing of the Israeli regime, check-

points were islands functioning on Israeli time, no matter where

they territorially existed. I had also learned that at the checkpoint,

communication with a soldier, if it happens at all, doesn’t go very far.

That particular discrepancy of time lasted only a few weeks, until

both Israel and the Territories were back in the same time zone. But

I walked away from the checkpoint that evening with a nagging

thought: Israeli time had already “sprung forward” yesterday, and

the Palestinians were lagging behind. It hinted at a larger metaphys-

ical quandary: a complex imposition of “Israeli time” onto Palesti-

nian temporality.

What does it mean that the checkpoint marks different time

zones? Was it that Israel’s measurement of Palestinian time was cal-

culated according to a different logic, one in which Palestinians’ time

was not as valued? What does it mean that various temporalities

butt against each other at a checkpoint? Was it that the checkpoint

seemed simultaneously premodern, modern, and hypermodern (be-

cause of the crude force used to contain populations; because of

eighteenth-century ideas on the need of surveillance, discipline,

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

386 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

and governance; because of the progressively disembodied technol-

ogies of control used)? Certainly, checkpoints defy and redefine qual-

ifications related to time and offer different layers of time. But what

do these slippages suggest?

This article deals, first, with analyzing “checkpoint time”: how

does the material site of the checkpoint mark, make, and represent

a particular temporality? Rather than focus on checkpoints as spa-

tial separators, I focus on their temporal work, asking how check-

points have enabled temporal archipelagoes—not just spatial ones.

Second, what does such a twisting of time do to Palestinian togeth-

erness or sense of community? In a sense, then, this article asks:

What does a checkpoint “say” about Palestinian temporality? And

what does that in turn tell us about the relationship between time,

communication, and community? How does a checkpoint define

and enable different kinds of interactions between Palestinians, be-

tween Palestinians and soldiers, and between Palestinians and the

space of Palestine? The rupture that checkpoint time engenders is

a power dynamic that structures Palestinianness itself.

More than a Space

Checkpoints exist in space. One can find them today throughout the

West Bank, surrounding the Gaza Strip, on roads leading to Jerusa-

lem, encircling some cities and villages, or at a specific number of ki-

lometers outside Ramallah, for example. Checkpoints accomplish

spatial work: they cut across streets and valleys, separate and enclose

communities, define and control the flow and speed of traffic. They

are also embedded in and change the geography around them with

concrete blocks, fences, walls, buildings, bus depots, parking lots,

turnstiles, corrugated roofs, metal gates, and so on. In short, they

are material spaces made up of specific technologies and practices

that engender particular embodied and territorial experiences.

Implicit in positing checkpoints as spatial objects is the fact that

they also exist in time. In the West Bank, for example, checkpoints

emerged in full force in the 1990s and early 2000s. The Qalandia

checkpoint described above materialized in the fall of 2001. As

such, checkpoints have been situated specifically in the Territories

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 387

during the “peace” and “post-Oslo” years as part of a larger matrix

of (mostly territorial) control.4 Geographically and historically,

checkpoints have not been unique to Palestinians inside the Territo-

ries, as similar structures and practices have been imposed on Pales-

tinians in refugee camps in Lebanon, or on Palestinian communities

“inside” Israel since before 1948, to name just two examples. Thus if

we recognize checkpoints as bordering processes imposed on Pales-

tinians neither specific to the Territories nor to the post-1990s time

frame, they also exist across time. Indeed, the tensions of border

crossings and territorial containment are experiences shared by all

Palestinians since the early twentieth century—in diaspora, exile,

statelessness, or occupation.5 Their prevalence is precisely why Ra-

shid Khalidi opens his book on Palestinian identity with the follow-

ing statement: “The quintessential Palestinian experience, which

illustrates some of the most basic issues raised by Palestinian identity,

takes place at a border, an airport, a checkpoint: in short, at any one

of those many modern barriers where identities are checked and ver-

ified.”6 It should come as no surprise, then, that checkpoints and

roadblocks are tropes, metaphors, and actual spaces that emerge

in Palestinian films and literature and thus appear in cinema and lit-

erary studies.7 In short, checkpoints in both material form and as

emblematic of processes such as border crossings and im/mobility

have been a significant part of Palestinian life for more than seven

decades, both within and outside the Territories, engendering partic-

ular temporal and phenomenological experiences.

Whether approached as specific places or as symbols of something

else, checkpoints perform temporal work—a concern that remains

largely understudied, particularly in relation to the abundance of

scholarship that focuses on checkpoints’ spatiality and territoriality.

Moreover, checkpoints have existed alongside a variety of temporal

technics that have sought to differentiate and control Palestinians:

curfews, travel permits that denote when and for how long a person

can travel, work permits that specify which hours in a day a Pales-

tinian is permitted to be somewhere to work, among others.

The most common form of theorization that connects the check-

point to temporality has been that which has relied on thinking

through temporal inequalities and speed, echoing Paul Virilio’s

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

388 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

argument that geopolitics (a politics based in space) has been sup-

planted by chronopolitics (a politics based in time). Virilio’s work

demonstrates that speed privileges certain populations and restrains

others, that the experience of time is relative.8 Checkpoints subject

different populations to distinct time regimes. In analyzing the time it

takes to travel through a checkpoint, Ariel Handel argues that space/

time relationships and practices between Palestinians and Israelis are

radically asymmetric: Palestinians face difficulty, slowness, and un-

predictability, while Israelis experience time and space as predict-

able, fluid, and ultimately “modern.”9 Cédric Parizot complicates

this in recognizing that there are different speeds, depending on

who is attempting to cross a checkpoint: an Arab-Israeli, a Palesti-

nian Jerusalemite, a Jewish-Israeli, a West Banker, and so forth.10

The speed of one person versus another can be very different (slow

vs. fast) and varying (whether it’s always the same), and in some in-

stances mutually exclusive (one can pass only if another is stopped).

The work of Handel and Parizot helps situate Palestinians’ position

in a larger economy of temporal value. But this focus on different

time zones, or speeds, seems to miss the important point that multi-

ple temporalities can be—and are always—interdependent, relation-

al, entangled, or, as in this case, separate. Of course, the sharing of

space does not guarantee the sharing of time. But the structures that

make time’s passing different for one or another group demonstrate

the presence and diffused violence of the Israeli regime everywhere

and every day across Israel/Palestine. In other words, “Israeli time”

determines the relationship wherein experiences of time are relative

to one another.

Checkpoints are part of the political power dynamic between Is-

rael and Palestine. As Pierre Bourdieu suggests, “When powers are

unequally distributed, the economic and social world presents itself

not as a universe of possibles equally accessible to every possible sub-

ject . . . but rather as a signposted universe, full of injunctions and

prohibitions, signs of appropriation and exclusion, obligatory routes

or impassable barriers, and, in a word, profoundly differentiated.”11

The checkpoint promises to suspend time in the purging of risk and

danger for Israelis at the expense of Palestinians. In doing so, it dis-

avows a heterogeneous temporality. The unevenness, as it were, is

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 389

manifested in different ways. Handel, for example, demonstrates

how checkpoints are temporal in the sense that they are pervasive.

“Everything, both space and time, is measured in terms of before or

after the checkpoint, and there are no assurances that another check-

point will not pop up around the bend,” he writes of the West

Bank.12 In other words, the power of checkpoints is in their spatial

and temporal ubiquity, in their constant possibility of being present.

Certainly, in their early days—in the late 1990s and early 2000s—

checkpoints marked the precarity, arbitrariness, and flexibility of

time in a different way as well, for back then “mapping checkpoints

[was] an absurd exercise of documenting the shifting temporal land-

scape of occupation—a map created today does not necessarily re-

flect what was yesterday and could likely be obsolete tomorrow.”13

As I spent more time studying checkpoints and returned to them

at varying intervals of days, months, and years, they struck me as

markers of the movement of time—places where one sees changes

from one month or one year to the next, for example in their chang-

ing architecture. Any Palestinian (or person familiar with the check-

points) confronted with an image of a specific checkpoint would be

able to identify when the image was taken by looking at the structure

itself or the graffiti around it, whether the wall was already built,

whether there was a parking lot or a bus lane, and so on. The phys-

icality of a checkpoint changes over time: what may have started out

as a temporarily staffed roadblock now sits along the security fence/

wall; is made up of hundreds of tons of concrete, CCTV cameras,

and automatic turnstiles; and has twenty-four-hour surveillance.

Yet checkpoints equally mark the stoppage or suspension of time.

Indeed, after spending so much time ethnographically observing the

checkpoint, I wrote that “every day feels like the next or the previ-

ous: as if time never moves here. For in a sense it doesn’t. The check-

point slices and cuts across Palestinian life, transforming Palestinian

space-time into one of constant transience, impermanence, volatility,

sometimes simply standstill.”14 Checkpoints slow down the flow of

traffic and people. Daily and weekly activities are defined by the

presence (and unpredictability) of checkpoints. The inordinate and

unpredictable amount of time spent waiting at a checkpoint, and in

different spaces within the checkpoint, not only adds up day after

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

390 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

day but fundamentally changes one’s disposition to one’s own sense

of and control over time, and its relationship to Palestine.

Palestinians are ripped apart by mechanisms imposed by Israel

that are nothing short of what Sari Hanafi has termed “spacio-

cide”: annihilating the space of Palestine and its everyday experi-

ences.15 In bringing the temporal into the analysis about the space

of the checkpoint—in unpacking its everydayness—I seek to reveal

the distressed temporality that is engendered in spacio-cide. Taking

into account a checkpoint as an anthropological space from which

to understand larger questions about Palestinian mobility, resis-

tance, and fragmentation for example, I ask: what kind of time ex-

ists in the space of Palestine?16 Ultimately, my concern is to think

through the relationship between time and communication, between

temporality and a public: do distorted time and space—which a

checkpoint exemplifies—make a public possible?

Theorizing Time

In thinking about the relationship between space, time, and the

public, I draw primarily on media and cultural studies and anthro-

pology. Time is a central problematic understood as a parameter

of communicative possibility, and, simultaneously, time’s ordering

is a sociopolitical and cultural manifestation of specific and situated

power dynamics.

Media and communication theorists have long analyzed the role

of time and temporality, contending with questions of synchronicity,

simultaneity, and feedback. For example, Harold Innis and Ithiel

deSola Pool foreshadowed analyses of the time-space warping dy-

namics of capitalism (such as David Harvey’s notion of space-time

compression) by analyzing the kind of temporal and geographic

distances or proximities made possible by different technologies

of mediation.17 Others have analyzed the extent to which media

technologies are often attempts to “shrink” distances between peo-

ple in the search for “true” or profound communication.18 Radio

and television have provided fodder for thinking about flow, seg-

mentation, and liveness, although what constitutes “liveness” in a

media-saturated environment pertains to more than the realm of

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 391

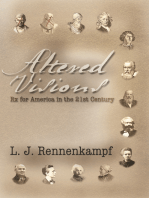

Fig. 2. A turnstile and corridor. This is an unused set outside the

checkpoint, perhaps stored for future use. The same contraption is

used inside the checkpoint. Qalandia, 2015

broadcasting.19 Media scholars are now contending with “new” me-

dia’s role in (re)structuring our time, the crises that structure new me-

dia temporality, or how contemporary “speed” is the commanding

by-product of a mutually reinforcing complex that includes global

capital, real-time communication technologies, corporate productiv-

ity demands, military technologies, and scientific research.20 That we

are living in a 24/7, always-on and on-the-go world, which has been

theorized in media studies by scholars such as Jonathan Crary, con-

tinues to be the assumed starting point for much critical analysis of

globalization, labor, and democracy.21 Drawing on philosophers as

far back as Plato, I build on an implicit argument in media studies:

the sharing of time is a condition for communication.

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

392 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

This crucial point is summarized by Johannes Fabian: “For hu-

man communication to occur, coevalness has to be created. Commu-

nication is, ultimately, about creating shared Time.”22 Fabian’s con-

cept of coevalness highlights the importance of a togetherness that is

both synchronous and simultaneous (occurring at the same physical

time) and contemporary (as in co-occurrent). Coevalness is a com-

mon, active sharing of time. Coevalness is necessary for communica-

tion. And communication is necessary for collectivity—whether the

formation of a public such as one based on class, national identity, or

otherwise.23 Time is at the core of Benedict Anderson’s discussion of

nationalism, for example: the modern perception of time as a chro-

nological continuum has facilitated the development of the national

idea.24 Thanks to technological, economic, and cultural changes—

such as the advent of newspapers—the nation can imagine itself as

operating simultaneously and moving in unison on the same time

axis. Nationality is not only an ideological, social, or economic phe-

nomenon but also a temporal one constructed through rhythms that

define how the components of the national story will be arranged in

relation to one another.25 What this scholarship makes clear is that

chronological time sequence is necessary for meaning making, com-

prehensibility, and the formation and recognition of collective iden-

tity. Control over time is a main expression of human action, as are

perceptions of history, units of time, control over time, and products

of long-term conflicts between social (primarily national) groups. In

short, time is not simply a measure or a vector but a constituent of

culture, and it is so because it is one of the most important means of

communication.

Time is also a form of power. In Discipline and Punish, Michel

Foucault described how the regulation of activity proceeds from dis-

tribution in time: how timetables, for example, constituted a mech-

anism of control, as well as how such measurable time was set to

increase “the quality of the time used”—to waste less time, to be

more productive.26 Such a calculation has been made in the context

of checkpoints, as, according to Amal Jamal, “the act of detaining

Palestinians at roadblocks empties their time, transforms their lives

into ‘valueless’ entities.”27 Foucault’s work also demonstrates that

time is a site of material struggle, creating social differences and

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 393

inequalities structured in specific political and economic contexts.

Timekeeping is a way of imposing order, distance, or power. Build-

ing on Foucault’s and Giorgio Agamben’s work, Michael Hardt

further suggests that “time is the measure of power, and once a sov-

ereign power has our time it is loath to let it go.”28 Meanwhile, time

discipline also structures people’s abilities to make decisions about

their activities, and thus it has important repercussions for individ-

uals’ subjectivities. Foucault’s infamous example of the prison is not

far-fetched here. That control in prison was exercised through the

control of time is salient, for the feeling of incarceration is prevalent

at a checkpoint. Carceral geographers, criminologists, and prison

sociologists’ approach to the temporal is suggestive here. Such schol-

ars, as Dominique Moran argues,

have developed a sophisticated understanding of prisontime . . . high-

lighting the overlapping temporalities which exist within carceral

space, such as the externally imposed clock time which measures

sentences in days, weeks, months and years, and the experiential

time as experienced by individual prisoners, who variously sense

stasis (with time seeming to stand still while they are incarcerated

through the daily repetition of penal routines), who perceive time

to flow more quickly outside the prison than inside (as events in

the lives of others seemingly pass them by), or who observe the

passage of time biologically (through their own embodied pro-

cesses of ageing and attendant physical deterioration).29

The comparison of Palestinian containment via checkpoints with in-

carceration demonstrates the unevenness of temporalities, how con-

trol over time leaves individuals more vulnerable to control, and

how the inability to control time prevents its organization and un-

dermines the individual’s and society’s sense of being.

This comparison can be pushed still farther, as both checkpoints

and prisons are built and discursively framed as necessary for (some

people’s) security. Here we come back to another concern dealt with

in media studies about our crisis-ridden, preemptive, “securocratic”

world. As Brian Massumi argues, our “temporalization” of the po-

litical has been focused on the growth of “pre-emptive security”

strategies, rhetorics, and technologies that have emerged as central

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

394 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

to the conduct of the global “war on terror.”30 The checkpoint is

(partly) a manifestation of a security apparatus, which has a tempo-

ral dimension that entails projecting a particular political order or

set of power relations into the future. A checkpoint is an anticipatory

governance strategy premised on controlling the unfolding of the fu-

ture through preemptive intervention in the present. The checkpoint,

then, is as much the opposite of the (Western) high-speed, always-on,

24/7 world as it is a result of the proliferation of anticipatory gover-

nance and control strategies. What this suggests is not simply that

the checkpoint prevents action in the present as well as in the future

but that, more broadly, the checkpoint gives us a glimpse of all of

our futures. It is accepted by now that Palestinians are treated as

guinea pigs whose lives and spaces and temporalities are a testing

ground for new military technologies, new forms of urban warfare,

new forms of political exclusion.31 As Nasser Abourahme states,

“Checkpoints can be thought of as a kind of built microcosm of wid-

er reality: the physical-architectural mark of the lived political trau-

ma.”32 The impact of Palestinians’ temporal experiences reverberate

much farther than the space of the checkpoint.

Taken together, the scholarship above confirms that time is lived,

time is power, time is relative, and that time is a material struggle.

Moreover, as a power dynamic, “the temporal is political regardless

of speed and present. . . . It is an enduring political and economic

reality with important cultural effects.”33 It is through this under-

standing of temporality’s politics and its constitution of people’s ex-

periences that I approach the checkpoint. Checkpoints mark and de-

fine Palestinian temporality; they disrupt time and the possibility of

Palestinian coevality. It is to this disruptive power that I turn next.

Checkpoint Time(s)

Material formations of checkpoints have changed over the decades,

becoming increasingly stringent and inaccessible. Despite these changes

and despite there being no such thing as a generic checkpoint, they

share a particular architecture, a logic, by which I mean that from

the perspective of the Palestinian attempting to get “out,” check-

points are generally structured in a similar fashion. To get at the

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 395

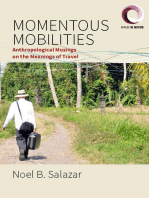

Fig. 3. Inside the checkpoint. After having passed through turnstiles

and metal corridors and given his ID card to a soldier behind the

window (on the right), this man is waiting for his belongings to come

out the X-ray belt (on the left), before going through the last turnstile

to exit. In this space—deep inside the checkpoint—one normally goes

through alone. Qalandia, 2015

checkpoint’s temporal work, I describe here the process of going

through one.

First, one knows that one is approaching the checkpoint because

taxi services or bus lines abruptly end, enormous traffic jams erupt,

and hundreds of people are suddenly making their way toward

a particular place. Second, one encounters a large waiting area—

sometimes covered with a corrugated roof, sometimes exposed to

the open air and butting up against the wall—lined with metal

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

396 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

barricades, surveillance cameras, and signs. People flood at a fren-

zied pace into this waiting area. People forge ahead, although there

are always those who are waiting for someone to catch up, who

pause to buy a coffee or a sesame roll from men who have set up

stands over the years. Something like a set of queues forms, but it

helps to visualize this as a triangular mass trying to make its way

into a siphon. A set of turnstiles is the first contrivance through

which people must pass, making their way from cramped chaos

into a funnel. These first turnstiles—operated by remote control

by an unseen Israeli soldier—lead toward a narrow corridor lined

by metal barricades, above which are surveillance cameras, razor-

barbed wire, and sharp metal arrows. People press into each other,

suffocating those “ahead” up against the metal barricades and

against the turnstiles. There is no routinized tempo: the speed at

which the turnstile unlocks and keeps rotating is determined by

the unseen soldier. By virtue of the narrowness of the corridor (about

eight meters long by sixty centimeters wide), people are forced to

squeeze into a (dis)orderly queue. At the other end of this corridor

is another remote-controlled turnstile, most often unlocked at a

slower tempo than the first: the barricaded corridor fills up at a faster

rate than it is emptied, often forcing limbs or excess weight to bulge

between the bars. It’s more the space (or lack thereof) that forces the

formation of a queue than the people in it. At fifty-five centimeters

wide, the turnstiles are extremely narrow (compared to seventy-five-

to ninety-centimeter-wide turnstiles used at Israeli bus stations, for

example). Only one person can fit at a time; heavier-set people, peo-

ple holding infants, and pregnant women cannot, let alone those in

wheelchairs. Once jammed inside the corridor, one slowly inches up

to the second turnstile, constrained with the growing pressure from

behind. When the second turnstile is remotely unlocked, a person en-

ters what can be thought of as the main security hall, where bright

fluorescent lights give the space a vapid, sinister feel. Directly in front

is an X-ray conveyor belt on which to place bags and personal be-

longings. To the right is a thick, opaque, bulletproof Plexiglas win-

dow. The Plexiglas looks as if it were lined with a pasty film, making

it difficult to see more than a few centimeters in to where Israeli sol-

diers sit; one is more likely to see one’s own reflection. At the bottom

of the window is a tiny horizontal slit for identification cards,

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 397

permits, and paperwork. Unlike at a bank, there are no perforations

in the Plexiglas to allow for a direct auditory experience: the soldier

speaks through a loudspeaker, the Palestinian speaks into the air

teeming with microphones and video surveillance cameras. People

now wait to be explicitly told—over the microphone—that they

can move on. Then they are permitted to pass through a full-body

scanner and pick up their belongings from the X-ray conveyor belt,

where another soldier (or two or three) may conduct a more thor-

ough search; ask them to step aside for a pat-down, to step inside

the office for interrogation, to be sent back; or ignore them altogeth-

er. The wall to the right is lined with more opaque Plexiglas, behind

which are more soldiers. All along the left side are barricades. If ap-

proved to pass, there is one last remote-controlled turnstile to pass

through before being let out altogether. By this last turnstile, the flow

has become a trickle—from a gush to a protracted drip—making one

wonder if some, or how many, bodies disappeared along the way.

The turnstile clicks; with this last push, one has made it out.34 There

is usually no roof over the exit, which makes the sunlight beam-

ing down jarring—it is more than a metaphoric light at the end of

the tunnel.

As a person going through the checkpoint, the next step is to

proceed—until the next checkpoint. For the purposes of this article,

however, we need to rewind and suspend our focus on each step de-

scribed above. By slicing the description into the checkpoints’ differ-

ent junctures, I zoom in on the kind of temporality that is engendered

and analyze the spheres of interaction and communication made

possible at each juncture.

One’s first personal encounter is with a merchant: a bus driver, a

taxi driver, a coffee seller, a peddler, a kid or old man selling gum.

These merchants are located along what can be thought of as the pe-

riphery of the checkpoint—along the road where the traffic slows

down, in the parking lots, outside the corrugated-roofed hallways

or right inside them. Even if one buys a cup of coffee every day

from the same merchant, interactions are based on monetary ex-

change. Communication is basic, contractual, although it does not

mean it is not friendly. Given that many people must pass through

the checkpoint day after day, those who are prone to purchase a cof-

fee or a snack will usually, as in any recurring commercial exchange,

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

398 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

know the merchant’s name and have a hurried chat before moving

on. Ayman, for example, has been running a coffee/food stand at

Qalandia since 2002, and most people who must pass the check-

point regularly recognize him as well as the changes he makes to

his stand—over the years it has grown from a cart to a van to a metal

container eventually painted bright yellow. Since this exchange does

not yet technically take place “inside” the checkpoint, I am only pro-

viding a cursory description.35

Palestinians are forced to go through a checkpoint—because rare

are the people who pass through the checkpoint because they want

to, and even rarer are those traveling through on a whim, as a permit

to pass is needed. The primary reasons for going through are one’s

job, school attendance, a doctor or hospital visit, or a family visit. By

far the most people moving through checkpoints need to do so be-

cause of work. Collectively, all checkpoint passers face a politically

unstable future and endless loss of rights and dignity at the hands of

the Israeli regime; as workers, most of them are also exploited labor-

ers inside Israel.

The crowd of male laborers between 3 and 5 a.m. is a haunting

scene. They arrive early because there is no knowing how long—or

if—one will get through the checkpoint. They have no control over

their time: they do not know if they will get to work on time (if at all)

and must wait for their turn to come through the first turnstile, into

the corridor, and through the next turnstiles. There is lots of shoving,

pushing, cursing. Even if some workers are trying to get to the same

factory, office, or construction site, there is no solidarity between

them while here. The checkpoint might close or the turnstile be fro-

zen for an inordinate amount of time. Every person wants to—needs

to—make sure that he or she is ahead. There is no sense of together-

ness: these atomized beings are a mass inevitably about to get frag-

mented by the turnstiles. They are all collectively trying to beat the

clock, although the clock here is the click of the remote-controlled

turnstile. There is a palpable corporeal frustration, especially during

high-traffic times, that did not exist in previous years; before turn-

stiles, before tight corridors, before soldiers were hidden behind opa-

que windows and walls. From a bird’s-eye view it’s a constantly shift-

ing crowd; from up close, it’s an ugly contest.

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 399

One dark morning, standing with Ayman near his coffee stand,

we watch a fight develop in the space leading to the first turnstile.

A man is eventually dragged out from the crowd with a bloody

nose and comes to rest in front of Ayman’s stand. Later, after the

man leaves, Ayman declares: “There’s a brawl every morning! Peo-

ple fight each other even though they’re all in the same situation.”

People are put into competition with one another, and exchange be-

comes for the most part tense, competitive, angry, selfish. People

punch or elbow each other, curse, spit, shove. Ayman expounds:

“There is a perfectly logical way of explaining what is going on. Peo-

ple are taking their frustration out on each other because there is

no other room for them to do so. Neither can they fight against

the occupation forces, nor can they fight against the [Palestinian

Authority].” Notwithstanding the poignant critique against the Pal-

estinian Authority, Ayman was alluding to the shrinking possibilities

of where, when, and how “resistance,” or even simply frustration,

can be expressed. What he was also suggesting is how connection

is structured through the regime of the checkpoint itself: disconnect-

ing people, suspending the possibility for communal resistance, emp-

tying their existence in a phenomenological sense by atomizing

individuals and a larger collective from one another.

People press into each other to form a line, funnel into the turn-

stile, compress into the barricaded corridor, and wedge into the next

turnstile. At each passage one waits for an unknown period of time.

This process is unpredictable and contingent: people never know

whether they will get shut in one of the turnstiles (which happens of-

ten) or for how long; whether they will be stuck in the barricaded

corridor, with how many others; and whether this “togetherness”

will last minutes or hours. As Julie Peteet points out, “Although clo-

sure attempts to routinize confinement and subdue resistance, it is

equally about rule through the imposition of calibrated chaos.”36

People are trained to listen for the “click” of the turnstiles and to ac-

cept that their fate and time is not under their control. This kind of

instituted (dis)order is suggestive of what Bourdieu refers to as abso-

lute power, which “has no rules, or rather its rule is to have no

rules—or, worse, to change the rules after each move, or whenever

it pleases.”37 Having made it through the turnstile, the corridor, and

the next turnstile, people never know that they won’t be turned away

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

400 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

at the checkpoint, or that if they make it through the checkpoint,

they will make it through the next one, or this same checkpoint on

their way back home later in the day, tomorrow, or the day after.

This unpredictability denies one any reasonable anticipation, evok-

ing Bourdieu’s explanation of absolute power as the power to place

other people “in total uncertainty by offering no scope to their ca-

pacity to predict. . . . The all-powerful is he who does not wait but

who makes others wait.”38

Power is not simply exerted in forcing people to wait; it is also in

having them stay put. Entering the first turnstile through the corridor

and then the second turnstile, people find that there is no way out.

They are stuck inside, constrained in a space that is oppressive and

dehumanizing: harsh, colorless, made of concrete and metal, with

soldiers booming incomprehensible commands over loudspeakers,

bone-chillingly cold in the winter, unbearably sweltering in the sum-

mer. It can take a minute to get through the checkpoint, or it can take

hours. Deep inside the belly of the checkpoint, between the barri-

cades and the turnstiles, the present remains motionless. Time be-

comes measurable, fragmented into a series of nows relegated into

spatial instants. These frozen “nows”—inside the turnstile, in the

corridor, in the next turnstile, in front of a mirrored window—block

the multiplicity of the future and suspend all possibilities. The check-

point imposes the abstract “now” over temporal possibility, freezing

the moment on the edge of the tragedy. Henri Bergson calls “measur-

able time” a sequence of “nows” in which time remains spatially ex-

ternal to what determines it. Time becomes measurable only when it

is made divisible—and it is divisible because it is space. To put it dif-

ferently, time becomes measurable “because it surreptitiously rele-

gates duration to spatial instants.”39

This disjunctive temporality produces deep ontological insecurity:

there is no continuity, stability, or routine. There is no ability to plan

ahead, no ordered sequence, no continuous narrative, no cause and

effect. One’s present time is occupied with itself and overdetermined

with the moment and its immediate consequences. Existence here

does not plot itself on a chronological time line but collapses in on

itself. People look down at their feet, stare at the back of the head of

the person in front of them; there is no room to move or shift.

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 401

Suspension in time is a crisis-ridden experience, suggesting powerless-

ness with respect to time as well as to the possibility of self-expression

within time. Inside the barricade, between the two turnstiles, there is

barely any communication. Whatever loudness existed in the shov-

ing and pushing to enter this funnel has now turned into an eerie

silence punctuated with the occasional curse, prayer, or grumble.

Traveling through a checkpoint is a confining and asphyxiating

experience.

Each person is physically alone but further classified and separat-

ed as existentially alone by the soldier, or the entire apparatus, that

renders a Palestinian a unit that can be separated from the others

also attempting to get through the checkpoint. Whether people ar-

rive at the checkpoint with their children in hand, their whole fam-

ily, their coworkers, or an emergency medical team, they can pass

through each mechanism only by themselves, at whatever tempo it

happens to be. Each person is atomized. Solitude is the fundamental

experience at the checkpoint: one is concerned only with the present

task of waiting to maybe pass through and, it bears repeating, wait-

ing without knowing how long the wait will be. The atomization is

furthered by desocializing each person from others.

There is nothing to do but wait, and wait alone. Undeniably,

waiting has become a mode of Palestinian life. But it is not simply

for those chopped up by checkpoints, for those under curfew evoked

by Darwish’s poem quoted above, or even for the refugees for whom

waiting has become permanent; it is for all Palestinians. Drawing on

Palestinian cinema and literature, Nadia Yaqub declares that Pales-

tinians are always on the road, but a road that leads nowhere.40 Pal-

estinians are collectively in-waiting, and, as Darwish hints at, they

are in-waiting for the waiting to end. This stuckness in waiting

has been experienced since at least 1948, since the time at which

“all Palestinians share an experience of suspended time that lacks

normal continuity. All Palestinian communities everywhere confront

the same temporality crisis: a festering sense of temporariness, the

suspension and emptying of time, of waiting.”41 Waiting is a perma-

nent companion.

Waiting, here, is less than waiting: akin to remission, quiescence,

discharge, exemption. Prolonged and unpredictable waiting has be-

come part of the structure of Israel’s rule. This kind of waiting is

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

402 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

evocative of “prison time.” As Hardt suggests, prison time, an “ob-

vious form of punishment in our world,” is a temporal nothingness

that exists purely as a sentence, a punishment.42 The usefulness—no

pun intended—in comparing checkpoint time to prison time stems

from the similarity of one’s phenomenological experience. “Inmates

live prison as an exile from life, from the time of living,” Hardt sug-

gests; they are forced “to grapple with one of the most intense meta-

physical problematics and they suffer a properly ontological malady.

They are constrained to an existence separate from being—this is

their exile from living.”43 Without the ability to “own” their tempo-

rality, they cannot be. As criminologists and prison sociologists have

recognized, the very fact of being in prison changes how prisoners

experience time. The “now” of incarceration takes the form of an

extended present, Moran explains, in which each new moment of

imprisonment is added to the past as a moment of memory, shaping

prisoners’ thoughts and feelings about their past and their future, as

well as their sense of the passage of time.44 And while there is an

awareness of clock time, its flow does not feel continuous and regu-

lar. Whether individual people are stuck inside the turnstile, or the

social structure more broadly is stuck between walls and check-

points, universalized standards and tools of time measurement—

such as hours, days, months, day and night, wristwatches, timers,

clocks, and calendars—lose their relevance. When imprisonment

goes on for so long and the days of one’s sentence cease to be num-

bered, time stops.45

The arbitrariness of what happens inside a checkpoint in terms of

soldiers’ control of Palestinians’ time is further comparable to forms

of solitary confinement. According to Martel, the three key charac-

teristics of coerced isolation are flexible rationales for confinement

and isolation, the meticulous planning of architectural and spatial

dimensions, and the subjectification of those isolated. Martel further

explains, “In the absence of comprehensive narrative spaces delin-

eating the use of prison segregation through legislated boundaries,

provincial prison employees and decision makers are virtually un-

constrained in their practice of segregation. Pretty much everything

is open to interpretation!”46 The same is true of a checkpoint: there

are no rules, and there is no way to know what a procedure is, if

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 403

there is one at all. Checkpoints do not exist on official maps, but they

do exist in different time zones. There is no crime that the Palesti-

nians committed, nor is there an elaborate calculus for how much

time their “crime” equals. (Even if these details are arbitrarily decid-

ed, there are generally matrices: theft equals six months, murder

equals ten years, etc.) Palestinians’ temporal experience is not simply

arbitrary (albeit driven by a colonial logic) but also temporarily per-

petual. The unpredictability and longevity of isolation and life sen-

tences have parallels here: time is an unknown factor or too long

to make much sense. In certain ways, checkpoints—like isolation

cells—are empty informational spaces.

If prison time is one comparison, unemployed time is another.

Bourdieu’s analysis of the unemployed’s time posits that uncertainty

about the future is an uncertainty about one’s social being, and that

“the extreme dispossession of the subproletarian . . . brings to light

the self-evidence of the relationship between time and power.”47 The

unemployed “can only experience the free time that is left them

as dead time, purposeless and meaningless.”48 If time—per Martin

Heidegger—is time to do something, for the unemployed there is

no possibility of doing. The person becomes “dispossessed of the

power to give sense, in both senses, to his life, to state the meaning

and direction of his existence, he is condemned to live in a time ori-

entated by others, an alienated time.”49 At the checkpoint, it is the

soldier, the apparatus, and the Israeli regime—in that click of the

turnstile—that dispossesses the Palestinian. For Bourdieu, too, the sig-

nificance is profound: “What truly is the stake in this game, is not the

question of raison d’être . . . but of a particular, singular existence,

which finds itself called into question in its social being. . . . It is the

question of the legitimacy of an existence, and an individual’s right

to feel justified in existing as he or she exists.”50 The unemployed—as

the imprisoned—is a person without a future, “living at the mercy

of what each day brings and condemned to oscillate between fan-

tasy and surrender, between flight into the imaginary and fatalistic

surrender.”51 Whether unemployed or imprisoned, the experience

of time is suspended under the control of a dominant force. So

too for Palestinians: “Palestinians cannot foresee the duration or

the outcome of waiting. Time has stopped, robbing them of their

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

404 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

individuality as subjects.”52 Here the checkpoint is evocative of so

much more than itself, stripping life of everything but the time of

waiting—waiting for that waiting’s end, isolated, estranged.

As the turnstile clicks, people almost fall over from the pressure of

the pushing bodies. They can’t exhale, however, as an even more

tense experience awaits. They place their bags on the belt and step

to the right to slide their ID card in the slot under the Plexiglas. Now

their “identity” is assigned in a manner typical of the highly asym-

metrical sociopolitical exchanges between Palestinians and the Isra-

eli regime. It is a process that empties the subject’s individuality as it

renders identity a bureaucratic measure and abstracts the subject

from the object determining the identification—be it a soldier or, re-

ally, an invisible force behind the screen. Political decisions both near

and far can impact the experience, but as far as anyone knows, every

decision is arbitrary.

Whatever existential disintegration has taken place up through

the turnstile goes a step farther here because of the invisibility of

any human beings. All other Palestinians have been left behind,

and all that remains in front is one’s own murky reflection. As Jamal

perceptively states:

The Palestinians cannot communicate their distress; the soldiers in

their glass booths escape any burden of moral reflection conse-

quent to direct physical contact with suffering people. . . . The sol-

dier’s isolation from the privations of the waiting Palestinians

mirrors the technical isolation of Israeli society from the daily suf-

ferings of Palestinian society in the OPTs [Occupied Palestinian

Territories]. Communication becomes too difficult, and reconcil-

iation impossible.53

Palestinians for the most part deal not with their “oppressor” direct-

ly, or even with a regime per se, but with the architecture pressing

down on them, squeezing them between various metal and con-

crete formations. There is no room for a Palestinian to encounter—

let alone communicate with—an Israeli here (never mind that the

only Israeli in the vicinity is in military uniform).

Merchants who have set up shop at the checkpoint for more

than a decade now arguably have a broader view of these changes.

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 405

On another morning Ayman and I were listening to a forecast of

snow. It brought back a memory from a few years earlier. “You re-

member during that snowstorm we had snowball fights with the sol-

diers! Now there is no soldier to throw a snowball at. We neither see

them, nor even know if they’re coming or going,” he says. These

“exchanges” are increasingly mediated, technologized, abstract, dis-

tanciated; over the years interaction and communication take place

through remote controls, loudspeakers, Plexiglas windows, one-way

mirrors, surveillance cameras, biometric strip readers, binoculars

peeping out of watchtowers, and so on. There is a range of tech-

nologies that make this possible: clocks, timetables, soldiers’ work

shifts, maps, databases, X-ray machines, turnstiles, sensors, scan-

ners, and the like.54 These help organize power into forms of spatial

and temporal surveillance whereby each Palestinian is measured,

classified, and separated. The consequence of indirect interaction

with soldiers is that people increasingly take out their frustrations

on each other (whether they are about running late, the checkpoint’s

presence, the occupation’s abstraction, colonialism’s expansion, or

something else). Solitude is experienced through spatial and tempo-

ral segregation, but it is even more profound because it renders col-

lective response or resistance impossible. Fabian’s coevalness is not

even a distant possibility here. Communication, community, and the

formation of a public—and thus any political change—are not pos-

sible. Checkpoints prevent “Palestinians from questioning their

‘fixed’ national culture, prevent associations with the outside and

with each other. Checkpoints serve to further split, and erase, the

Palestinian ‘nation.’”55

The architecture, the sound clicks, the booming microphones, the

walls—all of these impose a particular disposition. This disposition,

or “thingness[,] . . . has become all that much more impressive—

indescribable—to the point of obfuscating, silencing and rendering

invisible any humanity, whether of those who still have to pass

through here, the handful of merchants who still loiter around but

seem more like beggars, the bus drivers, even the soldiers behind

their bullet-proof glass, mirrors, and databases.”56

Of course, technologies have made it harder to interact interper-

sonally, corporeally, or face-to-face with soldiers. But the inability to

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

406 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

address the soldier or, more broadly, the regime does not exist simply

because of increased mediation and technologization—although

these certainly matter. The process of passing through checkpoints

renders one impotent. The most poignant remark made during my

research remains a statement by a young woman in 2003: “I get

there [the checkpoint]. I see them [the soldiers], I see the gun, I forget

everything I had just told myself [about wanting to resist the sol-

diers]. . . . I see the huge line [of people waiting] and my thoughts,

my strength evaporate. Nothing. I feel beaten before my turn has

even come.” Considering how the checkpoint—let alone the larger

political situation—has become so much more intractable over a de-

cade later, the young woman’s powerlessness makes for a bleak

prognosis. Her sense of imprisonment is corporeal as much as it

is figurative: fighting against Israeli occupation and colonialism

seems increasingly futile. The suspension of possibility and futurity

is totalizing.

The checkpoint also suppresses one’s ability to communicate.

First, despite advances in the technologies used to run the check-

point, use of technology for communication by Palestinians, such

as mobile phones, is not possible. Israeli policies block cellular sig-

nals at most checkpoints. A Palestinian cellular user cannot call

anyone from Qalandia—neither another cellular user on the same

network nor one on an Israeli network with whom Palestinian pro-

viders have roaming agreements. “Israeli signals are not available

there . . . for the simple reason that Israelis do not travel through

the area. Qalandia is a telephonic no-man’s-land—quite appropri-

ate, since it is, from an Israeli perspective, also a political and terri-

torial no-man’s-land, despite being a busy and bustling location.”57

Second, the checkpoint renders one mute because the place and its

experience are often indescribable:

I find it impossible to describe. I can tell you about the concrete

blocks and slabs, the wall on one side, the wall on the other

side, walls on every side; about the roundabout, the watch towers,

the layers of fences, the paved walkways, the gates, the metal tire

piercers to stop one from reversing his car; and those automated

turnstiles, the x-ray machines, the biometric scanners, the glass

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 407

behind which sit soldiers, the loudspeakers, the flashing lights,

more automated turnstiles. . . . But no! I do not want to describe

it, for to describe it would be to deny that the Qalandia I love is

dead, and that this “thing” before me today—“the Qalandia ter-

minal” as the Israeli military calls it—is what constituted its

death.58

The checkpoint does not allow the Palestinian to speak. Whether

in the dramatic passage above or in the young woman’s words, the

pervasive sense of impotence, powerlessness, and a shrinking future

is echoed in still another example that highlights the muting of po-

litical power, the shrinking realm of political possibility, the shrink-

ing realm of the struggle, and the shrinking realm of the nation. In

2003 I am standing with a taxi driver, staring at a queue of cars

stretching for more than a kilometer in a rural area in the northern

West Bank. We have already been waiting for hours. He erupts:

“Wow!” He whistles, staring at the long, immobile line, and contin-

ues: “Our national struggle is shrinking. It used to be fighting against

the occupation. Now we feel victorious if all we do is get through the

checkpoint!” If thirty years ago the dream was to overthrow the en-

tire occupation, and fifteen years ago it was to get from one part of

the country to another without checkpoints, by 2005 it had con-

tracted to simply getting through the checkpoint. In fact, only a

tiny number of Palestinians are even given a permit to pass through

a checkpoint, and those who can obtain a permit often do not bother.

A man born in Jaffa and living in Ramallah explains to me in No-

vember 2014: “I am old now, I am allowed to get a permit to visit

Jaffa [Israel more often provides permits for people over sixty-five].

I always imagined that I would fly at the first chance. But I haven’t

been because I can’t bear having to go through Qalandia [check-

point].”

Palestinians remain hanging as “temporary subjects” of the occu-

pation, where the past has been pulled from under their feet, where

time is disintegrated from its being endured, where the future is

a dead end. Achille Mbembe calls “emergent time” the feeling of

absence in which both past and future horizons are fading.59 But

the checkpoint demonstrates how these have already faded. It is a

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

408 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

more pessimistic read, to be sure, because it has to be read alongside

the temporal displacement and dispossession under which Palestinians

have been excluded from past and future time. Being inside the

checkpoint is not simply a state of in-betweenness toward an antic-

ipated future, because what lies ahead is not a probable outcome but

a certainty: of being inside the turnstile, inside the checkpoint, of

doing this again tomorrow.

Palestinian temporality is itself perpetually in waiting: people

must linger; landscapes are obliterated; connections between one

place and another are severed; continuity between one time and an-

other is amputated; political concerns zoom in on trying to get

through the checkpoint or survive within its confines, rather than

contend with the more macroscopic affairs of an entire territory or

nation. There is not simply a lack of shared space; there is also no

shared time. Without shared time, there is no communication, no

community, no public. The implications are tremendous, and they

are best stated in a recent joke: “The Arab Spring was on its way

to Palestine but got held up at a checkpoint.”60

Palestine at the Checkpoint

The above joke can be tweaked to iterate a more extensive point:

Palestine is stuck inside the checkpoint. The checkpoint demon-

strates how Palestinians live with(in) a disruption of the chronolog-

ical continuum of past-present-future, a disruption that undermines

both the individual’s and society’s very sense of being. More so, as

Abourahme states: “The issue is not simply that the multiplicity and

unevenness of various senses of social time becomes [sic] more

apparent—it is that these timespaces are increasingly isolated, cut

off, estranged from one another in a present that seems to have

come to a halt.”61 The checkpoint, as I explained above, disrupts

the temporality for those passing through and stuck inside it, but

the checkpoint is equally significant because the temporality it en-

genders speaks to how the control/loss over time has been an integral

component of the conflict and Palestinian life since at least 1948.

The checkpoint tells us something more than just its own imme-

diacy: it “communicate[s] our shared experience of the loss and

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 409

on-going search for temporal stability.”62 If the checkpoint were to

speak, it would echo the predicament of Palestinians’ disordered

space-time, which, as Edward Said posited decades ago, is marked

by “the dislocations and unsynchronized rhythms of disturbed

time.”63 More specifically, the temporality that has been imposed

on Palestinians has resulted in this discombobulation. Indeed, as

Sean McMahon states, “Palestinian-Israeli politics, or more specifi-

cally the Zionist colonization of Palestine which defines these poli-

tics, is about nothing if not time.”64 It is to this larger concern that

I shift now.

In Zionist ideology as well as its practice across Palestine/Israel,

Jewish national identity is based on a continuum that skips over

two thousand years of Jewish exile and creates a direct link between

the ancient and modern settlement of the Jewish people in the Land

of Israel.65 Zionism created an explicit link between national aware-

ness and existence in historical time, creating a Jewish national awak-

ening within the framework of modern, progressive time. Time was

argued to have been lost to the Jews because of historical events out-

side their control. With the creation of a nation-state, time would be

“returned” to them.66 This becomes a core myth in Zionist political

thought. Zionism is thus a collective effort to “return” to modern

history and establish new temporal standards for Jewish existence,

expressed in the dynamic figure of the pioneer–cum–national hero

who resurrects Jews from history and leads them on their modern

journey.67 This historical narrative, an inseparable part of the Jewish

claim for Palestine/Israel, serves as justification for Jewish settle-

ment. Jamal explains, “This effort has existential implications not

only for Jews, viewed as carriers of modern national time, but also

for Palestinians, who pay the price for Jewish time by being expelled

from history.”68

As a national and modern movement, Zionism suspended Pales-

tinian time and replaced it with Jewish time, thereby nullifying Pal-

estinian time by declaring it empty of meaning. In what can be seen

as an ironic twist of positions, Zionist time expelled Palestinians

from their own time and ejected them from history, suspending

“their temporal development for the sake of advancing its own.”69

Palestinian time’s existence outside the modern time frame is best

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

410 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

observed at the checkpoint, where it has been rendered worthless by

the machinations of the Israeli state.

Policies instituted in the early days of the Israeli state—structured

by Zionism—have enduring impacts on Palestinians. While law, ter-

ritory, and demography certainly defined Israeli colonialism, struc-

tural inequalities were exacerbated at the level of time. In the imme-

diate aftermath of 1948, Palestinians were categorized by the new

state according to their location in space and time: laws about citi-

zenship and landownership were passed not simply about who was

or was not there but about when and for how long.70 Zionist legal

policies transformed time into measurable entities, separating differ-

ent types of people who then move along different chronological

timelines. Jews were and continue to be “unlimited by time and

place; they can freely move along their historical axis without dam-

aging their inherent connection to the homeland.”71 While all Jews

were entitled to Israeli citizenship irrespective of their place or time

of residence (if they had ever lived in Israel), Palestinians were par-

celed according to whether they were residents in certain areas after

a date arbitrarily determined by the Israeli authorities. Palestinians

were fragmented into “sub-sectors, differentiated by a time-related

key”: some were permitted Israeli citizenship upon proof of living

in “Israel” (i.e., in their own homes since before the state appeared)

continuously between 1949 and 1952; some whose land was expro-

priated were rendered “present absentees” (an oxymoron both spa-

tial and temporal); and those refugees exiled from their homeland

were considered living outside Israeli time and historical time—as

they still do.72 As Jamal explains, segregation between Jews and Pal-

estinians was effectuated by delineating time by means of physical

barriers: checkpoints are only the most contemporary example in

a long-standing practice of disrupting a coherent Palestinian time.

Time’s instrumentalization through legal, territorial, and political

initiatives did not end with early Zionist settlement. Instead it seeped

through various aspects of the relationship between the Israeli state

and Palestinians. McMahon demonstrates, for example, how polit-

ical initiatives and “agreements” posit Palestinians as existing out-

side time: “Palestinians are constituted as being without time. They

are not with time; not with a past, or a future. . . . Palestinians are

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 411

denied a position in time. They are only ever of a time, and they are

not for time.”73 As he explains by dissecting various “peace” accords

and negotiations, “Palestinians have existed only for a time: five

years in the case of Oslo I, two years in the case of the Road Map,

and a proposed ten years in the case of Obama’s initiative.”74 Pales-

tinians are temporary at best. Indeed, the West Bank and Gaza Strip

are concomitantly the “eternal Jewish homeland” yet “temporarily

occupied.”

But temporariness requires stages of progress toward an antici-

pated (better) future, whereas “temporariness” here is experienced

by generation after generation of Palestinians as a frozen present.

The temporary has a way of morphing into longevity; as Julie Peteet

states, “for Palestinians the temporary is distorted.”75 Refugee camps

were erected as temporary, just as settlements were initially declared

temporary—the growth and perpetuation of both, since the late

1940s and the 1960s, respectively, contravenes any claims to tempo-

rariness. Likewise, closure has been imposed as a temporary measure

since 1991, just as checkpoints (in their modern manifestations)

emerged as temporary a few years later. Palestinians’ experience

has been subsumed by the “temporary” that grows ever more per-

manent every year. In the words of David Theo Goldberg, “Perma-

nent impermanence is made the marker of the very ethnoracial con-

dition of the Palestinian.”76 Adi Ophir and Ariella Azoulay draw this

rhetoric to its logical end: because the occupation is temporary,

Palestinians are governed as temporary human beings.77 This “tem-

porary temporality is taken as ontological condition much as political-

military condition. The Palestinian is always between, always ill-

at-ease, homeless at home if never at home in his homelessness, if

anyone really could be. . . . Shifting, shiftless, unreliable, untrustwor-

thy, nowhere to go, nowhere to be, the persona of negativity, of

negation, of death’s potential. He is the quintessential Nobody . . . ,

almost already dead.”78 The condition is more than existential, for

just as the end of Palestinians’ displacement is spatially and tempo-

rally displaced, so too is the end of the conflict displaced.79 All of

these presumably temporary schemes—refugee camps, closure, po-

litical agreements, and so on—have morphed into longevity. In fact,

the Israeli military’s terminology for checkpoints since 2005 best

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

412 qui parle december 2017 vol. 26 no. 2

demonstrates checkpoints’ and the broader condition’s spatial and

temporal intractability: they are now called “terminals.”

The terminal (in its temporal meaning) suggests that for Palesti-

nians, waiting is more than waiting: it is prolonged and unending,

taking one back in time, giving one the sensation of being left behind

in history. Palestinians are perceived and perceive themselves as

stuck in a system that belongs to the past, preventing them from

moving forward. It is as though Palestinians have unfairly been

left behind in the wake of a history that has granted others territorial

sovereignty. Abourahme calls this predicament the perpetual sus-

pended present: “trapped, seemingly perpetually, between the (end-

less) colonial present and the (deferred) postcolonial future.”80 This

can translate into a sense of amazement, fury, and hopelessness that

this (the occupation, colonialism, a geography pockmarked by walls

and checkpoints, what have you) is still happening. But if colonial-

ism belongs to the dustbin of history, so too does the Palestinians’

chase of an outdated mode of liberation. Palestinians are also well

aware—rendered more acute in their experience with Israel—that

territorial nationalism, even if the norm in world affairs, is rife

with violence and exclusionary practices. Thus Palestinians exist in

a situation that doubly belongs to the past, a counter-timeliness that

makes their situation seem especially perplexing.81 One can “think

of this Palestine as the tragedy of the postcolonial without the tri-

umph, however pyrrhic, of the anti-colonial.”82

The concreteness and continuous material fortification of walls,

bypass roads, and, of course, checkpoints bear Israeli colonialism’s

permanency. Time is central to the practice of colonialism. Coloni-

alism does not just take place in time. It constructs narratives of time,

in ways that create particular political relationships in the present,

and attempts to move itself through time to a certain political future.

Fabian writes:

When in the course of colonial expansion a Western body politic

came to occupy, literally, the space of an autochthonous body,

several alternatives were conceived to deal with that violation of

the rule. The simplest one, if we think of North America and Aus-

tralia, was of course to move or remove the other body. Another

Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/26/2/383/524515/383tawil-souri.pdf

by NEW YORK UNIVERSITY user

on 27 March 2018

Tawil-Souri: Checkpoint Time 413

one is to pretend that space is being divided and allocated to sep-

arate bodies. . . . Most often the preferred strategy has been simply

to manipulate the other variable—Time. With the help of various

devices of sequencing and distancing one assigns to the conquered

populations a different Time.83

The control over Palestinian time is critical to Israel’s colonial pro-

ject. But here we can complicate Fabian’s view of colonialism: it

does not only or necessarily move or remove the colonized; it can

also produce and reproduce their conditions toward particular ends.

Temporality is a facet of colonialism, and the “temporary” has be-

come part of the very logic of colonial governmentality. Palestinians’

temporality was yanked away first with the brutal slap of Zionist

colonization, followed by ongoing dispossession, exile, military rule,

occupation, a shrinking territory, and “peace” processes. Not only

is Israeli colonialism a continuous if uneven process, but the suc-

cessive distortions of Palestinians’ presence, territoriality, sociality,

communicability, and temporality invariably result in a state of af-