Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hardy - The Mayor of Casterbridge

Uploaded by

Vlad Chirca0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views10 pages.mn

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document.mn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views10 pagesHardy - The Mayor of Casterbridge

Uploaded by

Vlad Chirca.mn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

20

The Haunted Structures of

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Julian Wolfreys

Texts, ideas, the traces of historical and cultural forces: all take time to arrive. If they

arrive at all, chey are never on time, The arrival of che trace is radically disordered

from the start, If interpreted precipitately, texts miss being read and so semain co be

received. Yet the reader cannot help but be precipitate, overly anxious, of lageardly.

Moreover, any reception of some past trace always involves loss in translation, impov-

crishment through transmission, Thomas Hardy understood this more than most, and

‘gave expression co it in a commentary on the Dorser dialect poetey of William Barnes.

Interpreting, explaining, or annotating dialect words Hardy claimed, provided only

'a sorry substitute for the full significance the original words bear . .. without transla-

tion” (Barnes 1908: vii). From another perspective, Hardy knew that words and signs

arrive with a velociey that inevicably produces indirect, sensuous apprehension, cheteby

causing “a feeling before it gets defined” (Taylor 1993: 306). In this apprehension,

Hardy marks a distance from realist forms of narrative. Instead, he marks himself a

novelist of, and for, furure generations. Hardy is only ever available as other to che

times in which he wrote, In this, he remains the novelist of the nineteenth century

who, more than any other, affirms the past as always arriving. He is the novelist and

poet of cultural memory and the times of the other. In their transmission and critical

reception Hardy's novels come ¢o act on certain of their readers in a manner analogous

with the effect chat the many missives, celegrams, signs, paintings, and other modes

of communication that pepper his texts produce on and in his characters.

The historicized, historicizing modes of representation that inform Hardy's writing

‘mark and remark the time of theie having taken place, They thus record both image

and mencal image, che world and mental reflection on or image of that world. In this,

historicizing records ate themselves the craces of so many memento mori, so

‘many archived and archiving (recollections of heterogeneous traces, They are researches

into, remembrances of, times past. They affirm che ruins of che innumerable pasts

that crowd the present of so many of Hardy’s novels, signaling and sending themselves

into an unprogrammable futute, and risking everything on reading or unteadability

Acompain te Thomas y Kesh Win

300 Julian Welfreys

Whilst it has become something of a commonplace to speak of Hardy as a cinematic

novelist, ic is more accurate to remark that he shares with the technology of photog

raphy the ability co bear che burden of memory through the inscription of the haunt-

ing trace, as Tim Armstrong makes clear in his study of Hardy's poetry. OF

photography, Armstrong observes: “alongside its status as an index of the real, che

photograph itself becomes ghostly; it comes to represent mourning, abstracting and

escranging its subject-matter” (Armstrong 2000: 59). Such estrangement and abserac~

tion give one the sense of how intimately close and yet impossibly far Hardy is ftom

cour time, from the time we consider ours. To make us feel, rather than co make us

see, except by that indirect vision of insight, this it might be said is Hardy's desire,

his narrative and historical obsession. Hence, a complex textual weave emerges, com-

prising so many folds, and threads, so many echoes in different registers. Once a note

is sounded in Hardy, an impossible number of others resonate for the patient reader,

attentive to the difference of historicity, ics signs and traits

If we ate to be atcentive to the signs, races, and marks of history and che ways in

which the past leaves its remainders on our identities and our memories, we would do

well to acknowledge that “We ewo kept house, the Past and I,” as Hardy puts ie in

“The Ghost of the Past” (CPV 308). This is to confess to nothing less than the fact

chat ours is a ghost-ridden culture, We inhabit and share a modernity and a collective

identity in which we dwell and which we find to be haunted everywhere, by what

Hardy is pleased to call “the persistence of the unforeseen.” Nowhere in Hardy's work

is chis insistenc revenance acknowledged more persistently or blatantly a¢ various cul-

tural, historical, and personal levels than in The Mayor of Casterbridge. Specters ate

everywhere in what must be Hardy's most densely specteal novel and certainly the

novel that comes closest to being a ghost story. The dead and their spectral manifesta-

tions appear even in the faces or actions of the living. The town of Casterbridge is @

haunted place, its topographical, architectural, and archaeological structuses resonat-

ing with the traces of the spectral. The ghosts of other textual forms, of which the

tragic is only the most persistent of obvious, haunt the very structure of the novel.

especially is troubled by che past, by certain spectral retuens that

determine the ditection of his life and the choices or decisions he believes he makes

for himself. In this chapter therefore, 1 wish to examine how the various manifestations

of spectral revenance, in their eransgression of place, present, and representational

y, transform one’s understanding of time, place, and identicy

From one perspective, haunting is best, if provisionally, determined as the ability

of forces that remain unseen to make themselves felt in everyday life. Such interrup-

tion in the everyday causes us to anticipate, to fear, to act, or to respond in ways that

we do nor fully comprehend, supposing that we understand chem at all. As Keith

‘Wilson suggests of the novel, “all the major characters reveal a capacity . . . of respond-

ing to experience as the working-out of inevitable courses” (Wilson 1997: xxxi). This

assessment catches the sense ofa spectral movement of the invisible within the visible

Such haunting can also cause us to feel unsafe, uneasy, in places where we had always

felt at home, Haunting creates, then, the sense of the unfamiliar within che familias.

[es operation is thus a structural as well as a temporal disturbance. Haunting inhabits

The Haunted Structures of The Mayor of Casterbridge 301

and, in creating an uncanny response, manifests itself as not arriving from elsewhere,

bbuc instead makes itself felt, as Mack Wigley suggests, “surfacing ... in a recurn of

the repressed as a foreign clement that strangely seems to belong to the very domain

that renders it foreign” (Wigley 1993: 108). As we shall see, haunting, ghosting,

specteality are all necessary traces in the structures of The Mayor of Casterbridge. Barely

comprehensible, they inhere, haunting with an aggressive immanence the very places,

narratives, and forms they serve to articulate.

‘The persistence of the past in the narrative present of The Mayor of Casterbridge,

that unsettling of uncanny recurrence of the past trace described by Ned Lukacher as

“a strange peculiarity in the presence of the present” (Lukacher 1998: 156-7), pro-

duces also in the disturbed subject the structural sense of uncanny displacement and

doubling, that “uneasy sense of the unfamiliar within the familiar, che unhomely

within che home” (Wigley 1993: 108). Suzanne Keen draws the structural and tem-

poral strands together, offering a sustained consideration of “the return of the repressed!

in relation to “centuries-old tradition.” She considess also the persistence of “residual”

customs and forms, along with the “archaic survival” of equally “archaic practices” as

a temporal trace within the social spaces of Casterbridge and its cavitons in the novel's

present (Keen 1998: 127, 132, 134, 140). Tess ' Toole’s scudy of genealogical ps

terns and familial steuctuces in Hatdy also acknowledges the haunting trace: “as a

‘spectre,’ the genetic product is at once the reincarnation of a figure from the past and

an image that has been raised by a guilty parcy’s imagination” (O'Toole 1997: 18-19}.

Moreover, the spectral inhabits structure or identity in such a way as co displace or

dliscupe the propriety ofthe form from within. "Hardy's isa haunted arc... fin which]

material reality is displaced as the goal of representation by shadowy and spé

unrealities,” as Jim Reilly avers (1993: 65), reading Hardy as working within 2

tional paradigm that, chough indebted to mimetic realism, nevertheless disrupts that

realism repeatedly and violently feom within its owa conventions.

‘One prominent dimension of the spectral is that manifestation of the past in the

present, as I have said. The ghost of and from the past leaves its trace in the structures

of the present of The Mayor of Casterbridge. When we speak of the “past” in relation

to The Mayor of Casterbridge, chis might signal equally a number of tsaces, none with

any precedence over any others. OF personal returns and manifestations of the past

there are those who come back from Henchara's personal past: Susan, Lucetta, Eliza-

beth-Jane, even Newson, There is also the furmity woman, through whom the wife-

sale recurns to haunt Henchatd’s public identity, even as it has pexpetually haunted

his private sense of self. The impersonal past of Casterbridge is acknowledged in a

number of ways, not least the mayoral office, and the surrounding land (the Ring,

Mai Dun, Diana Multimammia, the history of the mayoral office). A rural past is

acknowledged through and craced in the return of events such as the fais at Weydon

Priors or the skimmington ride. Then there are the “past” texts that inform the steuc-

ture of the novel ~ Greek and Shakespearian tragedy, the Old Testament, references

to French novels, to Miltonic monsters, or the novels of Walter Scort, and Gothic

fiction. Such traces, of “remains” as Nicholas Royle describes them, are not “the

sal

remains of something that was once present.” They ate, instead, that which, in being

302 Julian Welfreys

spectral, prevents “any present, and any experience of the presence, from being

completely itself" (Royle 1995: 61). This ghostly trace has the ability co disrupt not

only the present moment but also any sense of identity. Ie may even write itself as

‘dead men’s traits” in the sleeping face of Elizabeth-Jane (MC 126).

This is not a simple or single instance in itself. Ie reiterates in part an earlier

moment in the novel, when Susan and her daughter return to Weydon Priors, che

mother's features being figured imperfectly in the daughter's as che manifestation of

‘Nature's powers of continuity” (MC 21). Thus, ghosting returns, while ehe revurn is

always ghostly. Furthermore, che earlier scene that anticipaces the haunting of

Flizabech-Jane is itself a recur. The question of the recurn is not limired to the

reiteration noted between the faces of the two women, as the text suggests. For as

Hardy tells the reader, “The scene in its broad aspect had so much of sts previous

character... chat it might... have been the afternoon following the previously

recorded episode” (MC 21). This is but one instance of the persistence of recusn as

evidenced through "particularities within a continuum,” which in turn establishes

the anthropology of a location... explicitly selating the behaviour of peesent indi-

viduals to that of countless predecessors” (Kramer 1987: xxii, xxii.

In chac we can read a doubling movement of revenance, where movement haunts

moment, we can suggest that the entire order of the novel is predicated on the troping

of zetua as the specttal pessstence disordering order and identity from within, a an

oxherness within the text. Even as Elizabeth-Jane's face is haunted by Susan's, and

even as chis recalls che earlier moment of recurn on the part of the wo women, so

that moment of retuen, in recalling the supposedly “initial” scene of arival a the faie

and the subsequent wife-sale, implies the continuous structural movement of displace-

ment and disjointing. To this can be added a reading of the wife-sale, not as some

simple or single originary event generating the unfolding of the narrative but as iself

a moment of «form of “azchaic survival” that, in eutn, belongs to forms of economic

trafic” that “structute the novel” (Keen 1998: 140). This “structuring” is also at the

same time a disturbance that inhabits the structure, disordering as the necessity of

an ordered form, as an inceenal “other” that haunts and makes possible the very

form itself. It distusbs the unity ot identity ofall stsuctutes, whether we ate speaking

of the human subject, an architectural form, the mapping of the town, of the form

of the novel

‘The spectral can be seen on occasions in acts of uncanny doubling, a form of recurn

For example, Elizabeth-Jane, on visiting her mother’s grave, encounters a figure “in

mourning like herself... {who} might have been her weaith or double” (MC 134).

Lucecta ~ she is the “wraith” ~ i also an uncanny double of Susan Newson/Henchard

fn one occasion, the “double of the fist” (p. 250). Flizabech-Jane is herself 2 double

of sorts. Not Henchard’s buc Newson's Elizabeth-Jane, she doubles even as she is

haunted by the dead child whose place she has taken, whose identity is signed and

simuleancously displaced in the reiteration of the name. That “Elizabeth-Jane” is a

proper name given co ewo characters sharing the same mother (whose features “ghost”

the second daughter’ face) is important. For ic alerts us co the importance of textual

The Haunted Structures of The Mayor of Casterbridge 303

haunting, of haunting as eextual, where even the act of writing can return, though

never quite signifying that which it had done, This is @ sign of repetition and dis-

placement, recurn and disturbance. In addition, Henchard sees in Farfeae’s face the

double of his dead brother (p. 49), and this has an “uncanny appeal for Henchard”

(Wilson 1997: xxv). Finally, Henchard is doubled (as is Lucetta) by the skimmingeon

ride effigy that, as Suzanne Keen so appositely suggests, comes “back to haunt him’

(Keen 1998: 140)

Keith Wilson speaks of the effects and Sgures of doubling in his introduction to

the novel (Wilson 1997: xxviii). Such patterns and the “phaneasms” of which they

are composed {for all involve the images and memories of the dead) do nothing so

much as signily the operations of each other, rather than intimating either a “reality

beyond the text of an origin or source of which the text is a copy. Indeed, the uncanny

‘motve)ment of revenance and disturbing reiteration comes from within a figure

face to disturb identity and disconcere the subject, In this operation, the ghostly trace,

which in ceiterating constantly operates in a manner similar to the simulacrum, “calls

into question the authority and legitimacy of its model” (Dutham 1998: 3). Such

doubling and the rhychm of reeurn of which ie is a part destabilize more chan the

identity of particular characters. It is disruptive of “distinct domains and temporali-

ties... {to} che excene to which they increasingly appear as the echoes or doubles of

cone another” (Durham 1998: 16). To put this another way, with direct reference to

‘The Mayor of Casterbridge, i¢ is not only a question of particular characters being

haunted. The various spatial and temporal boundaries of che novel that are found

increasingly to be permeable and capable of being transgressed signify one another's

functions and potential interpretive roles in the novel.

This is the case wherever one is speaking of the “haunting” of the present by the

past, signaled in che numerous returns discussed above, all of which permeace arbi-

tarily defined temporal boundaries. This can be read at the level of pascicular words

themselves. Through archaic, untimely words such as “burgh and champaign” (MC

30), the present of the narrative is disrupted. Words such as “furmity” and “skim

mingcon’ also signify an anachronic haunting; traces of other times and other modes

of expression, they remain ruinous and fragmentary, giving no access to some originary

discourse. Theteis also spatial movement across boundaries, which involves a temporal

emergence of residual archaic practices, as in the eruption of Mixen Lane inco the

‘propet” or familiar space of Casterbridge (Keen 1998: 132),

Keen successfully reads the structure and space of Mixen Lane as the “other” of

Casterbridge. Structurally internal to the town, part of it, this iminal site haunts the

town and yet retuens itself through the manifestation of “archaic practices of an ancient

caviron” (Keen 1998; 132). Its return is untimely and chetefore uncanny, displacing

the familiazity and domesticity of Casterbridge that Hardy has worked so hard (0

project. Yet Mixen Lane is but one figure in the novel simultaneously “at once removed

from and infinitely proximace to” (Durham 1998: 17) what we consider to be the

novel's presene moment and its present action. Thus the world of Michael Henchas

and the world of Casterbridge are distusbed in their identities feom within by the

304 Julian Welfreys

articulation of alternative structures ~ others of, within, and as a condition of textual

form — that signify, and thereby double, the operations of each other. Hardy's “use of

place resonates with personal and social significance” (Greenslade 1994: 55), but such

resonance is internally unstable, even as it destabilizes the form in which it emerges

While a form of return, such haunting is not simply a straightforward eemporal

acrival from some identifiable prior past. As J. Hillis Miller puts it, “These are under-

ground doublings which arise from differential interselations among elements which

are all on the same plane. This lack of ground in some paradigm or archetype means

tha there is something ghostly about the effects of this... type of repetition” (Miller

1982: 6). Speaking of Hardy's fiction in general, Miller motions towards a reading

that acknowledges the teiterative, the reciprocally interanimated, and the effect of

doubling that articulates Hardy's text. There is that which returns, though never as

itself In es untimely, not to say anachronistic, fashion, this spectral trace articulates

— or, rather, disarticulates ahead of either our comprehension of ability to see this

disturbance ~ a dissymmetry comprising a non-identity within identity

‘The phantom-text is everywhere. Not particularly Gothic in itself, chough none-

theless appearing as the trace of a reference, there is the doxical acknowledgment of

Susan as "The Ghost’” (MC 83), a “mere skellincon” (p. 85), Almost immediately

upon her death, Susan is reported as having something of a headstone appearance by

Mrs. Cuxsom: “And she was as white as marble-stone” (p.120). Susan is immediately

replaced in this comment, her face equated with ~ and ghosted by ~ the second- oF

thitd-hand signification of a material which will form the architectural symbol of

her being dead. Of Henchard, Nance Mockridge comments, in that knowing, pre-

scient manner peculiar to working women in Gothic novels, “There's a bluebeardy

look about en; and ‘ewill out in time” (p. 86). Not of course, that the Mayor has a

dungeon, nor does he chain Susan in it, yee his figure is haunted with a powerful

Gothic resonance. Moreover, Nance’s prediction points co the "persistence of the

unforeseen” (p. 334), as Hardy will put it on almost the final page (which statement,

would argue, is where all che specteal traces return from and to where they might

be read as leading us). Her phrase is both economical and excessive: itis an utterance

belonging to the cheapest of Gothic thrills, while also resonating in a somewhat

uncanny, if not haunted, fashion. Steucturally, therefore, her phrase, having to do with

time, is disturbed from within, being both timely and untimely, having co do

with the persistence of unreadable traces as a condition of temporal disturbance, wich

which the novel is so concerned.

Other characters are also marked in ways that suggest Gothic co:

is given a ghostly quality in relation to the question of the return, Specifically, he

disturbs Henchard: “The apparition of Newson haunted him. He would surely return’

(MC 300). Conjuror Fall lives outside the town, and therefore outside the boundaries

of society, as is typical of figures associated with alchemy and the black arts. His

habieation and narrative preparation for the encounter between Henchard and Fall

confuse discursive boundaries, intermixing the Gothic, the folkloric, and fairy-tale

‘The way co Fall’s house is “crooked and miey” (p. 185), and Henchasd!’s approach to

Fall’s home is suggestively eerie: “One evening when it was raining... heavily...

fention, Newson

The Haunted Structures of The Mayor of Casterbridge 305

shrouded figure on foot might have been perceived travelling in the direction of the

hazel copse which dripped over the prophet's cot” (pp. 1856). Even the furmity

woman gets in on the Gothic act, for, upon her retuen, ic is rematked that she “had

mysteriously hinted. chat she knew a queer thing or two" (p. 202). Of course, what

she knows is merely the information concerning Henchard’s past, but her return is

part of the general movement of eturn in the text, while Hardy carefully frames her

‘ominous comment in a manner designed co amplify its portentous aspect.

What will return in this instance is the narrative that alzeady haunts Henchard, as

the furmity dealer's citation, While the old woman returns, what returns through her

is the trace of the past and, with thac, che suppressed cruch as that which haunts

Indeed, Hasdy engages in « narrative economy of recusrence, by which teuth is appee-

hended as always revenant and revelatory. To put this differently, truth is always

spectral and is only known in its iterable appearances, as such, regardless of the logic

or rationality of a given narrative moment, The Gothic is one mode of production

that allows for an economy of explanation, a logic of representation, to order and

rationalize, even as i¢ relies on the non-rational. Yet within that mechanism, there is

always the spectral element. Gothie convention is precisely this: convention, structure,

and law. Within such convention, however, is that which is irreducible by explana-

tion, What cannot be explained is that the recurn happens, and that it happens

moreover not as the return of some presence to the present, but as the haunted trace

The truth of Henchard’s pase is coincidental co the general movement of spectral

revenance, which the Mayor of Casterbridge is incapable of reading, and which The

Mayor of Casterbridge bately glimpses

‘The technique of repetition at work throughout the novel provides this barely seen

spectral condition, even while, within the structures of the text, such reiteration is

locally domesticated through the recourse to particularly familiar textual forms, such

as the Gothic. Not only ate characters read and written as if in a Gothic context,

therefore. They behave as though they were characters from a Gothie novel, even as

the narrative voice mimics or is haunted by the trace of the Gothic. Elizabeth-Jane is

starcled by the apparition of Farfrac” (MC 136). Lucetta’s face is altered by an encoun-

ter with Fasfrae also: her face "became — as a woman's face becomes when the man

she loves rises upon her gaze like an apparition” (p. 178). There is something decid-

edly strange, uncanny, about Farfrae, that his appearance ¢o wo women should be

described as an apparition, on both occasions. It even disturbs Hardy in the act of

‘writing, for notice that pause signaled silently in the dash as the writer seeks the most

appropriate simile. However, we will have to leave the Scot for a moment.

There are other Gothic traces, too, improper references and ghostly citations

without specific origins. The keystone-mask above Lucetta’s door (MC 142) and the

decaying sign of the Three Mariners (pp. 42-3) have a certain Gothic appeal. Fur-

thermore, their ruined, decaying qualities hint at the uncanny, the unfamiliar within

the familiar. Suggesting forms of temporal persistence, of the past’s ability to return

and co disturb, they both sig ility chat gives the lie to che

familiasity and homeliness ofthe structures ~ the public house and Lucetta’s home — of

which they are synecdochie figures. Both serve economically in tracing that “structural

306 Julian Welfreys

slippage from heimliche [homely] to anbeimliche [anhomely} {in which] that which

supposedly lies ouside the familiar comfore of the home curns out co be inhabiting

ic all along” (Wigley 1993: 108). Most immediately however, cheir function is co

create that frisson so typically desired in the Gothic. Both the siga at

the keystone

serve a textual, that is to say a haunting, function, in that they remind us that a “house

is not simply an object chat may be represented, but is itself a mechanism of repte-

sentation” (Wigley 1993: 163), whereby in the perception of an image, one encouncers

a structure of iteration

‘We can read such effects at work when we are told how Jopp's cottage is “built of

old stones from the long-dismancled priory, scraps of tracery, moulded window- jambs,

and arch-labels, being mixed in with the rubble of the walls” (MC 221). Those scraps,

the euins of the priory, long since gone, operate as references in a number of ways

Priories are, of course, favorite ruined sites, often haunted, in Gothic discourse. There

is in this image, wich its fragmencs of clauses, che return of the past in the present

scructuse once more, the structuce of the cottage and the structure of the sentence.

‘The former is structurally (dis-)composed by the material traces of a former steucture;

the later is structurally (dis-}composed by the haunting traces of Gothic discourse

that, in their phantomatic inscription, enact a ghostly transference in che image of

the cottage, from its being simply an object co be represented, to being a mechanism

of representation. In this, the text does nothing so much as displace itself, endlessly

For the operation of haunting signals noe simply a prior moment, if that is even the

purpose, Instead, ic serves to signal a certain spectral dislocation that belongs to the

novel as a whole, signaling the ruins of other suins, che keystone, the decaying sign,

the Ring (chapter 11), even as ehey in turn signify other traces, and the other of the

trace, This movement, the Gothic “oscillation,” is not merely an intertextual feature;

iis of a different order.

‘The priory stones are therefore readable, as are other steuctural and architectonic

features, i. a manner similar to mote explicitly narrowly textual referents, such as those

from the Old Testament or tragedy, as we have already suggested, The “stones,” in

being the traces of an absent discourse, being performative fragments and rains, are

not there to suggest chat the reader simply turn back to the literary past, co some prior

form as the novel

inheritance of what might, oo blithely, be described as “context.”

Instead, they acknowledge an inescapably haunted quality within che structure of any

textual form. In this, they may be cead as signifying those other momencary, fleeting

textual aces, such as Hardy's reference co “The misrabler who would pause on the

semoter bridge” (MC 224). There is also that reference to Henchard’ face and the “sich

rong ot noir of bis countenance” (p. 67). The Mayor of Cavterbridge is peppered with

French words and phrases, enough certainly that criticism of the 1950s and 1960s

would doubtless have read such usage as past of Hardy's overceaching pretensions and

asiga of the text's lack of coherence. However, such “foreign” elements while disjoint=

ing the cext by their obvious, fragmentary “return” (they come to us from somewhere

that is neither Hardy's Wessex, nor his English), also, in the cwo examples above,

appeat to signal other novels, albeit in the most fleeting and undecidable manner. Are

The Haunted Structures of The Mayor of Casterbridge 307

these references to Hugo and Stendhal? Can we tell, can we be certain? The answer

cannot be an unequivocal rejection of such a notion, any more than it can be an aff

mative response, The momentaty inscription of another language appeats ¢o install

possible textual reference but, equally, remains undecidable as to its purpose, and thus

haunts the structure of the text. Both references do, however, have a somewhat Gothic

resonance. The miiérables are those who haunt che marginally located bridges, already

mentioned above. Rouge e noir, che coloring of red and black, is “Satanic” and is associ-

ated with Henchard throughout the novel (p. 35167).

There still remains, though, a question pertaining vo the trace of the Gothic,

which we can only acknowledge for the moment before moving on. Why does the

Gothic persist in Hacdy’s text? This may well be undecidable and chus belongs

to that order of disturbance within the structure of identity which the haunting

anachronic trace within the time of the novel causes to occur. What can be remarked,

though, is that Gothic discourse relies on the external sign — decaying ruins, mad

monks, skeletons, ghosts — disturbing the subject internally. The Gothic is in past a

structure of representation that generates unease, discomfort, and foreboding. One's

self is discurbed, haunted, by that which appears outside the self. Nevertheless, as in

any good Gothic tale, the frightened subject, for all che unsettling sensations, fre-

quently becomes obsessed with finding what might be behind those appatitions, chose

manifestations. We might suggest that this in part is the Gothic tale that haunts

‘The Mayor of Casterbridge for, inaugurated by a primitive act of the wife-sale, the novel,

is doomed to become haunted by chis first momenc, becoming in turn a story of

uncanny obsession, namely Henchatd’s, who finds significant signs everywhere

Without pursuing this further, mezely co hint at a possible way of reading events, it

is important nonetheless to register the internal disturbance, the production of the

uncanny precisely in the place where one should feel most like oneself ~ at home.

When Henchasd feels himself most ac home, as the titular mayor and symbolic

figurehead of the town, then haunting begins, the past returns, and everywhere the

forces of doubling and iterabiliey erupt.

‘We have seen already how devices of doubling and repetition, which are intrinsic

to the novel's steucture and identity, atticulate The Mayor of Casterbridge, and yet

disturb that very form from within. Thus, arguably, the entire novel may be consid-

cred as an exploration of the uncanny. There are numerous local and immediate

instances of the experience of the uncanny in the novel. Henchard feels haunted by

Newson, as we know already. Moreover, the reader is told repeatedly that he is a

superstitious man. Henchard is first revealed as “superstitious” through his decision

to visit Conjuror Fall (MC 185). Though this moment is not in itself uncanny (though

arguably Henchard's trip co Fall is meant co induce an uncanny sensation in the

reader), the next instance of Henchard's superstitiousness is, and deliberately so.

Henchacd is ruminating on his misfortune over the reckless crop selling

‘The movements of his mind seemed to tend to the thought that some power was

working against him.

308 Julian Welfreys

1 wonder,” he asked himself with eerie misgivings “I wonder if it can be that

somebody has been roasting a waxen image of me, of stiting an unholy btew to

confound me! I don't believe in such power; and yet — what if they should ha’ bees,

doing ie!” .. These isolated hours of superstition came to Henchard in time of moody

depression .. (ME 190-1)

While we may read the passage as remarking the residue of a superstition imbued

with the discourse of folkloric mythology, the passage is notable nonetheless for its

sense of the uncanny, of that internal power and the sensation of “eerie misgiving.”

Later, following the skimmington ride, we are told that “the sense of the supernatural

‘was strong in this unhappy man” (MC 297), In this assessment of Henchard's response

to the effigy there is che sense that Hardy may be read as explaining away the uncanny

feeling through recourse Co the idea of superstition, even as Henchard experiences

it. Yet uncannily, pethaps, that earlier speculation concerning the waxen image

may also be read as one more example of the “persistence of the unforeseen,” while

the effigy marks a form of return of Henchard’s fear, even as it physically cecusns via

the river,

Freud acknowledges that the writer, any writer, in creating uncanny effects in a

narrative world otherwise predicated on “common reality” through the use of events

that “never or rarely happen in fact,” appeals to the “superstitiousness” that we have

allegedly lefe behind (Freud 1997: 227). In a novel concerned so much with residual

forms of haunting, however, the very trope of superstition as archaic pre-modern

residue is readable as the uncanny manifestation of the haunting trace, Hardy's nar-

ative is constructed so as to reveal Henchard as haunted by superstition, while playing

oon the possible residue of superstition in the reader, and yet maintaining a di

from such isrational sensations by doubting whether “anything should be called

curious in concatenations of phenomena” (MC 204).

‘There ate, however, clearly uncanny moments for Henchard that have little or

nothing to do with superstition. Towards the end of his life Henchard is described

thus: “He rose to his feet, and stood like a dark ruin, obscured by ‘the shade from his

‘own soul upthrown’” (MC 326). One of the most complex and overderermined of

sentences in the novel, this delineation of Henchard addresses both his own being

haunted, suffering {rom the disturbance of the uncanay, and the uncanny haunting

to which The Mayor is prone, The ghostly citation with which the sentence concludes

traces a double movemenc at least. It comes from Shelley's Revolt of Inlam, as does the

phease “dark ruin,” While reading a citation, and one that, in its signifying operation,

refers us to those other ghostly citations, we are impressed by the figure, aot merely

of the soul, but of the “shade” also, Conventionally, the reading of that “shade” should

imply a shadow. However, there is also at work in this image the more archaic sense

of “shade,” meaning “ghost” or “specter.” The phtase “dark ruin” is itself a ruin, a

fragment, an improper citation that haunts the sentence and that does service as a

simile for Henchard, even as it echoes beyond the image of Henchard, or, indeed, any

animate creature, to hint at the Ring and other architectural sites and remnants out

of which Cascerbridge is composed, and by which i is haunted,

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- How To Work On The TranslationDocument1 pageHow To Work On The TranslationVlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Programa Clasa 3Document9 pagesPrograma Clasa 3Vlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

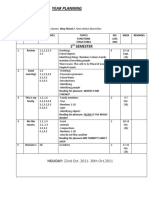

- Year Planning: 1 SemesterDocument4 pagesYear Planning: 1 SemesterVlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- 2017 2018 Grade V Annual Lesson Plan Limba Moderna 1limba Englezacambridgediscovery Educationlmhaninaby Prof - Simonette Tenido BrebenariulDocument5 pages2017 2018 Grade V Annual Lesson Plan Limba Moderna 1limba Englezacambridgediscovery Educationlmhaninaby Prof - Simonette Tenido BrebenariulVlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- 1Document1 page1Vlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Fisa Present Continuous Clasa A 4aDocument1 pageFisa Present Continuous Clasa A 4aZmirela Mire100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 0 ColoursDocument2 pages0 ColoursFlorentina DespoiuNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Animals I.What's This?: Example: This Is A CowDocument4 pagesAnimals I.What's This?: Example: This Is A CowVlad ChircaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)