0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views38 pagesUnderstanding Multiprocessor Systems

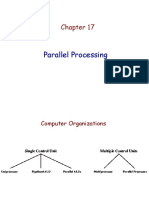

This document discusses multiprocessors and parallel programming. It begins by introducing multiprocessors and their scalability. It then discusses shared memory and distributed memory multiprocessor architectures. Programming multiprocessors is difficult because programmers must explicitly manage coordination and synchronization between processors. Parallel programs are also harder to develop than sequential programs due to the overhead of communication and coordination between processors.

Uploaded by

IsaacMedeirosCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views38 pagesUnderstanding Multiprocessor Systems

This document discusses multiprocessors and parallel programming. It begins by introducing multiprocessors and their scalability. It then discusses shared memory and distributed memory multiprocessor architectures. Programming multiprocessors is difficult because programmers must explicitly manage coordination and synchronization between processors. Parallel programs are also harder to develop than sequential programs due to the overhead of communication and coordination between processors.

Uploaded by

IsaacMedeirosCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd