Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Craswell

Craswell

Uploaded by

Navindra Jaggernauth0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views222 pagesWriting

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWriting

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views222 pagesCraswell

Craswell

Uploaded by

Navindra JaggernauthWriting

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 222

Writing for

Academic

Success

A Postgraduate Guide

Writing for Academic

Success

A Postgraduate Guide

GAIL CRASWELL

SAGE Publications

© Gail Craswell 2005

First published 2005

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or

private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication

ay be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by

any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the

publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in

accordance with the terms of licences issued by the

Copyright Licensing Agency. Inquiries concerning

reproduction ontside those terms should be sent to

the publishers.

SAGE Publications Lid

Oliver’s Yard

55 City Road

London ECIY 1SP

SAGE Publications Ine.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Led

B-42, Panchsheel Endave

Post Box #109

New Delhi 110 017

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 1 4129 03009

ISBN 1 4129 0301 7 (po)

Library of Congress control number 2004096556

‘Typesct by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain by Athenaeum Press, Gateshead

Managing the Writing

Environment

Developmental Objectives

By applying the strategies, doing the exercises and following the procedural

steps in this chapter, you should be able to:

+ Take a pro-active approach to reducing the psychological and physical

stress that typically accompanies academic writing and communication.

+ Identify a range of strategies for managing more efficiently yourself and your

writing in the context of your life commitments and goals.

+ Ensure results-oriented communication with your lecturers and supervisors,

including email communication.

+ Understand some cross-cultural challenges in terms of writing and

communication, why these exist and how you might address them.

It is common for graduates to experience ups and downs with academic writing

and communication. Your feelings of confidence, excitement, self-doubt,

disinterest, frustration, lack of motivation, isolation and so forth may alternate,

and itis important to recognize such mood swings as typical rather than unusual.

‘This chapter covers a broad range of management strategies designed to reduce

stress and improve the quality of your writing environment.

Effective self-management

While networking requires effort, it can be worth the investment of your

valuable time, particularly if you are enrolled in a longer research degree.

4 / WRITING FOR ACADEMIC SUCCESS

NETWORKING FOR SUPPORT

‘These networking strategies should help alleviate stress while contributing to a

greater sense of integration in the academic community at large.

Generate peer support: local, national and international Students in your

course or research group will prove an excellent support resource, so be pro-

active in making yourself known to them. Make contact too with the graduate

student organization within your institution, if there is one. Such organizations

usually provide a range of social and academic support, are often advocates for

resolution of issues of concern to graduates, and may represent graduates’

interests on important institutional committees.

Understanding more about what is going on for graduate students in

general can afford a welcome sense of solidarity. Ask whether there is a national

student organization representing graduate interests that you should know

about. Websites of these organizations can contain informative material

regarding the current status of graduate and research education in your country

(see for example: National Postgraduate Committee ). Government departments responsible for higher education

also produce publications that you might like to browse in, again with a view to

becoming more informed.

There are numbers of international graduate student and dissertation

support sites on the Intemet. Many enquiries about writing are posted on such

sites, as is copious information about ‘surviving’ graduate studies. Even joining

a chat group with other graduates sharing your interests can lend support -

discuss this possibility with peers and academics in your area.

One well-established international site is the Association for Support of

Graduate Students chttp://www.asgs.org/>, a US site that provides a news and

reference bulletin for graduates writing theses and includes Doc-Tilk, a free,

moderated email discussion list about doing a thesis (lots of useful tips). Another

is the Postgraduates’ International Network

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- True FalseDocument97 pagesTrue FalseNavindra Jaggernauth0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Standard For Portfolio Management 2017Document140 pagesThe Standard For Portfolio Management 2017Navindra Jaggernauth100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

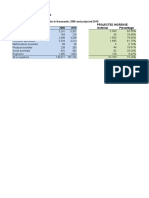

- Increased Revenues $10,000 $120,000 Increased Expenses: 14,000 Salary of Additional Operator Supplies Depreciation 12,000 Maintenance 8,000 90,000 Increased Net Income $30,000Document98 pagesIncreased Revenues $10,000 $120,000 Increased Expenses: 14,000 Salary of Additional Operator Supplies Depreciation 12,000 Maintenance 8,000 90,000 Increased Net Income $30,000Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- 9Document76 pages9Navindra Jaggernauth100% (1)

- CH 13 The Strategy of International BusinessDocument14 pagesCH 13 The Strategy of International BusinessNavindra Jaggernauth67% (3)

- Cape Mob 2015 U1 P1-2 PDFDocument7 pagesCape Mob 2015 U1 P1-2 PDFNavindra Jaggernauth100% (1)

- 7Document101 pages7Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- 5Document46 pages5Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- S1 S2 P1 P2 S1 0.20 0.60 0.30 S2 0.10 0.40 0.50Document111 pagesS1 S2 P1 P2 S1 0.20 0.60 0.30 S2 0.10 0.40 0.50Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Required: Method A Method B Method CDocument109 pagesRequired: Method A Method B Method CNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- $12,000 Favourable Nil $8,000 Favourable $6,000 UnfavourableDocument72 pages$12,000 Favourable Nil $8,000 Favourable $6,000 UnfavourableNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Leadership Competency Profiles of Successful Project ManagersDocument13 pagesLeadership Competency Profiles of Successful Project ManagersNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- CH 09Document69 pagesCH 09Navindra Jaggernauth100% (1)

- Testbank ch01Document11 pagesTestbank ch01Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Evans 2E Ch2 SolutionsDocument32 pagesEvans 2E Ch2 SolutionsNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Methods of Data Collection, Instruments and Advantages & DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesGroup 6 Methods of Data Collection, Instruments and Advantages & DisadvantagesNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- CAPEDocument12 pagesCAPENavindra Jaggernauth100% (1)

- Mob Internal Assessment FinalDocument19 pagesMob Internal Assessment FinalNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Com Jamaica LanguagesDocument3 pagesCom Jamaica LanguagesNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Based On The Findings of The StudyDocument3 pagesBased On The Findings of The StudyNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- MOB Unit 2 Past Papers PDFDocument17 pagesMOB Unit 2 Past Papers PDFNavindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet