Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Criminal Jury Instructions For RICO PDF

Criminal Jury Instructions For RICO PDF

Uploaded by

Jo CheyanneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Criminal Jury Instructions For RICO PDF

Criminal Jury Instructions For RICO PDF

Uploaded by

Jo CheyanneCopyright:

Available Formats

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.

2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime | July 2016 Update

Chapter 13. Substantive Crimes: RICO

II. Sample Materials

§ 13:31. Criminal jury instructions

References

RACKETEER INFLUENCED

AND CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS

(RICO)

CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS

SUBSTANTIVE AND CONSPIRACY CHARGES

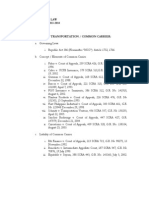

INDEX

1. RICO Instruction No. 1 RICO — Substantive

2. RICO Instruction No. 2 Person

3. RICO Instruction No. 3 Pattern of Racketeering Activity

4. RICO Instruction No. 4 Enterprise

5. RICO Instruction No. 5 Mens Rea

6. RICO Instruction No. 6 Associated With

7. RICO Instruction No. 7 Conduct or Participation in the Enterprise's Affairs

8. RICO Instruction No. 8 Interstate Commerce

9. RICO Instruction No. 9 Racketeering Acts — General

10. RICO Instruction No. 10 Racketeering Acts Nos. ___

11. RICO Instruction No. 11 Racketeering Act No. ___

12. RICO Instruction No. 12 Racketeering Act No. ___

13. RICO Instruction No. 13 Racketeering Act No. ___

14. RICO Instruction No. 14 Other Racketeering Acts

15. RICO Instruction No. 15 Unanimous Verdict

16. RICO Instruction No. 16 Statute of Limitations

17. RICO Instruction No. 17 Nexus Between Enterprise, Defendant, and Racketeering

Activity

18. RICO Instruction No. 18 Withdrawal

19. RICO Instruction No. 19 Multiple Enterprises

20. RICO Instruction No. 20 Proof of Seven Facts

21. RICO Instruction No. 21 Liability of Corporations

22. RICO Instruction No. 22 RICO — Conspiracy

23. RICO Instruction No. 23 Definition of Conspiracy

24. RICO Instruction No. 24 Cautionary Instruction Conspiracy—Hearsay

25. RICO Instruction No. 25 Membership

26. RICO Instruction No. 26 Mere Presence

27. RICO Instruction No. 27 RICO Conspiracy — Objective

28. RICO Instruction No. 28 Personally Agree

29. RICO Instruction No. 29 Overt Act

30. RICO Instruction No. 30 Unanimous Agreement

31. RICO Instruction No. 31 Withdrawal from Conspiracy

32. RICO Instruction No. 32 Statute of Limitations

33. RICO Instruction No. 33 Multiple Conspiracies

34. RICO Instruction No. 34 Proof of Acts

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

35. RICO Instruction No. 35 Forfeiture

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 1

(“RICO—Substantive”)

Count 2

The indictment charges that from on or about [Month, Year], and continuously thereafter up to on or about [Month,

Year], the Defendants committed the crime of “racketeering” in violation of a federal statute known as “RICO”.

Specifically, the indictment alleges that, from [Month, Year] to [Month, Year], the Defendants were “persons”

“associated with” an “enterprise” engaged in, or the activities of which affected, “interstate commerce”, and that they

knowingly and willfully “participated in the conduct of the enterprise's affairs” “through a pattern of racketeering

activity,” in violation of 18 U.S.C.A. § 1961 and 18 U.S.C.A. § 1962(c).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 2

(“Person”)

The term “person” includes any individual or entity capable of holding a legal or beneficial interest in property. 18

U.S.C.A. § 1961(3)

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 3

(“Pattern of Racketeering Activity”)

To prove a charge of “racketeering” under RICO, the government must prove as an essential element and beyond a

reasonable doubt that the defendants engaged in a “pattern of racketeering activity.” Congress gave a special definition

to the phrase “pattern of racketeering activity,” and it is the only one that you may use in deciding this case.

First, Congress defined “racketeering activity” to include any act in violation of Title 18 of the United States Code

(federal law) relating to mail fraud (18 U.S.C.A. § 1341), the sale and receipt of stolen goods (18 U.S.C.A. § 2315),

interstate travel in aid of racketeering (18 U.S.C.A. § 1952) and any act in violation of state law relating to bribery

(Section ___, ___ Penal Code).

Congress then defined a “pattern of racketeering activity” as “at least” two separate acts of “racketeering activity.” These

two separate acts must have taken place within 10 years of each other, and one must have occurred after October 15, 1970.

When I say that “at least” two racketeering acts are necessary to constitute a “pattern,” I mean that two racketeering

acts do not necessarily add up to a pattern. It is not enough for you simply to find that two crimes included in the

list of “racketeering activity” were committed. To find a “pattern,” you must find additionally that those crimes were

connected with each other by some common scheme, plan or motive, and that they were not simply a series of isolated

or disconnected acts.

In addition to being related, the acts must also amount to or pose a threat of continued criminal activity. “Continuity”

is both a closed- and open- ended concept, referring either to a closed period of related conduct, or to past conduct that

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

by its nature projects into the future with a threat of repetition. It is, in either case, centrally a temporal concept. A party

alleging a RICO violation may demonstrate continuity over a closed period by proving a series of related predicates

extending over a substantial period of time. Predicate acts extending over few weeks or months and threatening no future

criminal conduct do not satisfy this requirement: Congress was concerned in RICO with long-term criminal conduct.

Conduct forms a pattern if it embraces criminal acts that have the same or similar purposes, results, participants, victims,

or methods of commission, or otherwise are interrelated by distinguishing characteristics and are not isolated events.

The enterprise is not the pattern of racketeering activity; it is an entity separate and apart from the pattern of activity

in which the enterprise allegedly engages. Therefore, in every case the government must prove not only that there was a

pattern of racketeering activity, but also that it was conducted through an enterprise as thus defined.

There must be proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the facilities and services of the enterprise were regularly and

repeatedly utilized to make possible the racketeering activity, along with proof that the racketeering activity benefited

and advanced the enterprise, to establish the conduct of the affairs of the enterprise through a pattern of racketeering

activity.

Moreover, if you do not find that two “racketeering” crimes were committed, then you cannot find that a “pattern of

racketeering activity” existed. Finally, it is the government's burden to prove every essential element of each separate

alleged act of “racketeering activity” beyond a reasonable doubt. U.S. v. Phillips, 664 F.2d 971, 1039, 9 Fed. R. Evid.

Serv. 970 (5th Cir. 1981); Vietnamese Fishermen's Ass'n v. Knights of Ku Klux Klan, 518 F. Supp. 993, 1014 (S.D. Tex.

1981); U.S. v. Stofsky, 409 F. Supp. 609, 614 (S.D. N.Y. 1973); U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1331 (5th Cir. 1983);

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 2528–29, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

6100 (1981); U.S. v. Carter, 721 F.2d 1514, 1527, 84-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 9537, 14 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1613, 53

A.F.T.R.2d 84-1413 (11th Cir. 1984), vacated in part, 886 F.2d 304 (11th Cir. 1989); U.S. v. Webster, 669 F.2d 185, 187

(4th Cir. 1982); U.S. v. Thevis, 665 F.2d 616, 625, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1025 (5th Cir. 1982); U.S. v. Nerone, 563 F.2d

836, 851–852 (7th Cir. 1977); U.S. v. Erwin, 793 F.2d 656, 671 (5th Cir. 1986); Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., Inc., 473

U.S. 479, 496, 105 S. Ct. 3292, 87 L. Ed. 2d 346, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 92086 (1985); U.S. v. Brooklier, 685 F.2d

1208, 1222, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 703 (9th Cir. 1982); U.S. v. Starnes, 644 F.2d 673, 677–78 (7th Cir. 1981).

Activity Must Advance the Enterprise: U.S. v. Martino, 648 F.2d 367, 394 (5th Cir. 1981); U.S. v. Manzella, 782 F.2d

533, 538, 20 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 196 (5th Cir. 1986).

Activity Must Affect the Enterprise: U.S. v. Hartley, 678 F.2d 961, 999, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 128 (11th Cir. 1982)

(abrogated by, U.S. v. Goldin Industries, Inc., 219 F.3d 1268, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 9914 (11th Cir. 2000));

U.S. v. Scotto, 641 F.2d 47, 54, 107 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2288, 89 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 12285 (2d Cir. 1980) (rejected by,

State v. Haddix, 93 Ohio App. 3d 470, 638 N.E.2d 1096, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 8685 (12th Dist. Preble

County 1994))).

Interrelatedness of Predicate Acts Not Required: U.S. v. Gottesman, 724 F.2d 1517, 1522, 222 U.S.P.Q. 206, 15 Fed.

R. Evid. Serv. 98 (11th Cir. 1984) (abrogated by, Dowling v. U.S., 473 U.S. 207, 105 S. Ct. 3127, 87 L. Ed. 2d 152,

226 U.S.P.Q. 529 (1985)); U.S. v. Bright, 630 F.2d 804, 830, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 550 (5th Cir. 1980); U.S. v. Elliott,

571 F.2d 880, 899 (5th Cir. 1978); U.S. v. Weisman, 624 F.2d 1118, 1122–23, 5 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1338 (2d Cir. 1980)

(“enterprise” itself supplies unifying links among predicate acts); U.S. v. Qaoud, 777 F.2d 1105, 1116 (6th Cir. 1985).

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

What Constitutes Pattern (Relationship of Acts Mandated): U.S. v. Erwin, 793 F.2d 656, 671 (5th Cir. 1986) (quoting,

although not indicating approval of, the defendant's jury instruction that the government must prove that such offenses

were connected with each other by some common plan or motive so as to constitute a “pattern” and not merely a series

of isolated or disconnected acts). Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., Inc., 473 U.S. 479, 496, 105 S. Ct. 3292, 87 L. Ed. 2d

346, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 92086 (1985) (“continuity plus relationship,” rather than “isolated acts” or “sporadic

activity”). U.S. v. Brooklier, 685 F.2d 1208, 1222, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 703 (9th Cir. 1982). U.S. v. Starnes, 644 F.2d

673, 677–78 (7th Cir. 1981). Phelps v. Wichita Eagle-Beacon, 886 F.2d 1262, 1273–74, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH)

P 7320 (10th Cir. 1989) (Publication of two isolated articles on the same day insufficient to constitute a pattern). Edwards

v. First Nat. Bank, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 872 F.2d 347, 352, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7176 (10th Cir.

1989) (Bank officer's threats to borrowers presented no threat of continued illegal activity and hence did not constitute

a pattern. Unrelated threats to another borrower insufficient to prove a pattern.). U.S. v. Kaplan, 886 F.2d 536, 541–42

(2d Cir. 1989) (Two acts of bribery during one conversation may be considered in determining whether a pattern exists).

Recent U.S. Supreme Court Decision—Pattern—Schemes—Relationship of Predicate Acts: H.J. Inc. v. Northwestern

Bell Telephone Co., 492 U.S. 229, 109 S. Ct. 2893, 2899, 106 L. Ed. 2d 195, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7237,

103 Pub. Util. Rep. 4th (PUR) 513 (1989) (Multiple predicate acts which occur within the context of a single scheme

may form a pattern if they amount to, or threaten the likelihood of, continued criminal activity). Cases which have been

reconsidered in light of H. J. Inc. include: Walk v. Baltimore and Ohio R.R., 890 F.2d 688, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 7371 (4th Cir. 1989); Yellow Bus Lines, Inc. v. Drivers, Chauffeurs & Helpers Local Union 639, 883 F.2d 132,

132 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2164, 113 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 11530, 113 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 11669, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 7286, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7364 (D.C. Cir. 1989), on reh'g in part, 913 F.2d 948, 135 L.R.R.M.

(BNA) 2177, 116 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 10275, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7554 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (D.C. Circuit

agrees to rehear en banc).

Single Scheme Sufficient:

First Circuit: Fleet Credit Corp. v. Sion, 893 F.2d 441, 445, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7405 (1st Cir. 1990)

(Numerous mailings made over a four and one-half year period as part of the same scheme to obtain loans sufficient

to demonstrate “continued criminal activity[.]”); Second Circuit: Jacobson v. Cooper, 882 F.2d 717, 720, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7299 (2d Cir. 1989) (Single scheme to defraud, involving separate acts of fraud, dealing with several

properties over a period of years, is sufficient.); Polycast Technology Corp. v. Uniroyal, Inc., 728 F. Supp. 926, 947–

48, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94833 (S.D. N.Y. 1989) (Twenty-three acts of mail and wire fraud and violations of the

securities laws which occurred over an eight-month period were sufficient, even though all were committed in furtherance

of a single sale of a business.); Fourth Circuit: Morley v. Cohen, 888 F.2d 1006, 1010, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH)

P 7349, 29 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 205, 15 Fed. R. Serv. 3d 303 (4th Cir. 1989) (Single scheme involving two victims and

two perpetrators which occurred over five years is sufficient.); Combs v. Bakker, 886 F.2d 673, 677–78, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7317 (4th Cir. 1989) (Multiple acts of fraud relating to the sale of “Lifetime Partnerships” which

claimed 55,000 victims in independent transactions found sufficiently continuous to constitute a “threat of continued

criminal activity[.]”); Sixth Circuit: Newmyer v. Philatelic Leasing, Ltd., 888 F.2d 385, 396–97, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH)

P 94767, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7357 (6th Cir. 1989) (Single scheme which lasted over a period of five years

and which affected at least five victims sufficient.); Fleischhauer v. Feltner, 879 F.2d 1290, 1297–98, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 7254 (6th Cir. 1989) (Following the analysis outlined by the third and seventh circuits, the court finds a

single scheme committed over a period of time against some nineteen victims sufficient.); Obee v. Teleshare, Inc., 725 F.

Supp. 913, 916, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94914 (E.D. Mich. 1989) (Single scheme affecting single victim but involving

numerous solicitations over two years, was sufficient.); Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan v. Kamin, 876 F.2d 543,

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

545, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7222 (6th Cir. 1989) (Multiple billings to single insurer based on unnecessary

medical tests sufficient.).

Multiple Acts Not a Pattern When They Relate to a Single Scheme (See, H.J. Inc. v. Northwest Bell Tel. Co. which may

question the analysis of these cases.):

First Circuit: Framingham Union Hosp., Inc. v. Travelers Ins. Co., 721 F. Supp. 1478, 1484, 11 Employee Benefits Cas.

(BNA) 1825, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7433 (D. Mass. 1989) (Single scheme to defraud two victims over seven

years was insufficient.); McEvoy Travel Bureau, Inc. v. Heritage Travel, Inc., 721 F. Supp. 15, 16, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 7400 (D. Mass. 1989), judgment aff'd, 904 F.2d 786, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7478 (1st Cir.

1990) (Single scheme involving one transaction is insufficient.); Trundy v. Strumsky, 729 F. Supp. 178, 184, R.I.C.O.

Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7447 (D. Mass. 1990), vacated and remanded, 915 F.2d 1557 (1st Cir. 1990) (Nine-month

“Scheme” to take control of business is insufficient.); Second Circuit: Airlines Reporting Corp. v. Aero Voyagers, Inc.,

721 F. Supp. 579, 584–85, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7329 (S.D. N.Y. 1989) (Single scheme to breach a contract

involving a single victim and three perpetrators over a thirteen month period is insufficient.); Dooner v. NMI Ltd., 725 F.

Supp. 153, 161–62, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94769, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7370 (S.D. N.Y. 1989) (Single

scheme spanning an eighteen month period is insufficient.); Azurite Corp. Ltd. v. Amster & Co., 730 F. Supp. 571, 581,

Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94944, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7425 (S.D. N.Y. 1990) (Seventh-month scheme to

gain control of corporation, with no threat of continuity is insufficient.); Continental Realty Corp. v. J.C. Penney Co.,

Inc., 729 F. Supp. 1452, 1455–56, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7417 (S.D. N.Y. 1990) (Several acts of mail and

wire fraud occurring over the course of a single year and aimed at inducing a higher contract price insufficient.); USA

Network v. Jones Intercable, Inc., 729 F. Supp. 304, 318, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7419 (S.D. N.Y. 1990)

(Single scheme lasting some three and a half months is insufficient.); Utz v. Correa, 631 F. Supp. 592, 595, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6226 (S.D. N.Y. 1986); Third Circuit: Marshall-Silver Const. Co., Inc. v. Mendel, 894 F.2d 593,

597–98, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7404 (3d Cir. 1990) (overruled by, Tabas v. Tabas, 47 F.3d 1280, R.I.C.O.

Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 8754, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 8937 (3d Cir. 1995)) (Dismissal of a RICO claim

involving a single short-lived scheme); Peterson v. Philadelphia Stock Exchange, 717 F. Supp. 332, 336–37 (E.D. Pa.

1989), on reconsideration, 1989 WL 95553 (E.D. Pa. 1989) (Single scheme involving single victim, and two perpetrators

and occurring over the course of only a few months, is insufficient.); Ferdinand Drexel Inv. Co., Inc. v. Alibert, 723

F. Supp. 313, 331–31, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94942 (E.D. Pa. 1989), judgment aff'd, 904 F.2d 694 (3d Cir. 1990)

(Two mailings to a single victim within a single month is insufficient.); U.S. v. Freshie Co., 639 F. Supp. 442 (E.D. Pa.

1986); Fourth Circuit: U.S. v. Berlin, 707 F. Supp. 832, 837–38 (E.D. Va. 1989) (Single scheme lasting merely fifteen

months, involving isolated acts of bribery and wire fraud and affecting only one victim, was insufficient.); Parcoil Corp.

v. NOWSCO Well Service, Ltd., 887 F.2d 502, 503–05, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7348 (4th Cir. 1989) (Single

scheme to defraud, involving two perpetrators, one victim, and seventeen predicate acts, over a four-month contract

period, was insufficiently continuous.); Eastern Pub. and Advertising Inc. v. Chesapeake Pub. and Advertising, Inc.,

895 F.2d 971, 972–73, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7421 (4th Cir. 1990) (Single “Closed-ended” scheme, which

posed no threat of continuity and lasted three months, is insufficient.); Menasco, Inc. v. Wasserman, 886 F.2d 681, 685,

R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7321 (4th Cir. 1989) (Single fraudulent scheme, involving one perpetrator and one

set of victims, which occurred over a year, fails to constitute both a “special threat of social well-being” as well as a threat

of “continuity[.]”); Meadow Ltd. Partnership v. Heritage Sav. and Loan Ass'n, 639 F. Supp. 643, 650, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6417 (E.D. Va. 1986) (“pattern” requirement not satisfied where cast of characters, purpose, result

and alleged victim remained the same). Fifth Circuit: R.A.G.S. Couture, Inc. v. Hyatt, 774 F.2d 1350, 1354–55, R.I.C.O.

Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6101 (5th Cir. 1985) (rejected by, Lawaetz v. Bank of Nova Scotia, 23 V.I. 132, 653 F. Supp.

1278 (D.V.I. 1987)) (two related acts are sufficient even if part of single scheme); Smoky Greenhaw Cotton Co., Inc. v.

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Smith, Inc., 785 F.2d 1274, 1280–1281, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 92528, Fed. Sec.

L. Rep. (CCH) P 92767, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6221, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6269 (5th Cir.

1986) (undecided after Sedima opinion); Sixth Circuit: Fry v. General Motors Corp., 728 F. Supp. 455, 458, R.I.C.O.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7460 (E.D. Mich. 1989) (Predicate acts extending over a few weeks or months is insufficient.);

Seventh Circuit: Peterson v. Baloun, 715 F. Supp. 212, 216, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 95243 (N.D. Ill. 1989) (Single

scheme to defraud, involving one victim and one transaction, was insufficient; separate payment made in furtherance

of same fraud could not be used to transform that same scheme into two separate transactions.); Orchard Hills Co-op.

Apartments, Inc. v. Germania Federal Sav. and Loan Ass'n, 720 F. Supp. 127, 131–32, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH)

P 7380 (C.D. Ill. 1989) (Single scheme involving one transaction, one victim, and one distinct injury and threatening no

continued harm, is insufficient.); Flannery v. IFA Inc., 722 F. Supp. 498, 500–01 (N.D. Ill. 1989) (Single scheme to induce

employment insufficient.); Triad Associates, Inc. v. Chicago Housing Authority, 892 F.2d 583, 594–95, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7402, 15 Fed. R. Serv. 3d 477 (7th Cir. 1989) (abrogated by, Board of County Com'rs, Wabaunsee

County, Kan. v. Umbehr, 518 U.S. 668, 116 S. Ct. 2342, 135 L. Ed. 2d 843, 11 I.E.R. Cas. (BNA) 1393 (1996)) (Single

scheme to oust a security service in relation to a single contract, is insufficient.); Management Computer Services, Inc.

v. Hawkins, Ash, Baptie & Co., 883 F.2d 48, 51, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7292 (7th Cir. 1989) (A contract

dispute involving one victim, one transaction and two predicate acts based on the unauthorized copying of software was

insufficient.); Sutherland v. O'Malley, 882 F.2d 1196, 1204–05, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7288 (7th Cir. 1989)

(Single scheme to divert attorneys' fees which occurred over a five month period and involved only a single victim and

a single injury is insufficient.); Fleet Management Systems, Inc. v. Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., Inc., 627 F. Supp. 550,

553–60, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6218 (C.D. Ill. 1986) (rejected by, Lawaetz v. Bank of Nova Scotia, 23 V.I.

132, 653 F. Supp. 1278 (D.V.I. 1987)) (single scheme with eight predicate acts over two years is not a pattern); Eighth

Circuit: Superior Oil Co. v. Fulmer, 785 F.2d 252, 257, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6192 (8th Cir. 1986) (rejected

by, Ghouth v. Conticommodity Services, Inc., 642 F. Supp. 1325 (N.D. Ill. 1986)) and (rejected by, Lawaetz v. Bank of

Nova Scotia, 23 V.I. 132, 653 F. Supp. 1278 (D.V.I. 1987)) and (rejected by, Beck v. Manufacturers Hanover Trust Co.,

820 F.2d 46, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6643 (2d Cir. 1987)) and (abrogated by, H.J. Inc. v. Northwestern Bell

Telephone Co., 492 U.S. 229, 109 S. Ct. 2893, 106 L. Ed. 2d 195, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7237, 103 Pub. Util.

Rep. 4th (PUR) 513 (1989)) (numerous acts of mail fraud did not satisfy “pattern” requirement since there was no proof

of past crimes or crimes elsewhere); Tenth Circuit: Torwest DBC, Inc. v. Dick, 628 F. Supp. 163, 166–167, Fed. Sec.

L. Rep. (CCH) P 92524, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6196 (D. Colo. 1986), judgment aff'd, 810 F.2d 925, Fed.

Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 93106, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6507 (10th Cir. 1987); Eleventh Circuit: Hutchinson v.

Wickes Companies, Inc., 726 F. Supp. 1315, 1320–21, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7505 (N.D. Ga. 1989) (Two-

year scheme to convert the surplus of a pension plan insufficient.); Bank of America Nat. Trust & Sav. Ass'n v. Touche

Ross & Co., 782 F.2d 966, 971, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6189 (11th Cir. 1986) (abrogated by, Reves v. Ernst

& Young, 507 U.S. 170, 113 S. Ct. 1163, 122 L. Ed. 2d 525, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 97,357, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 8227 (1993)) (nine separate acts of mail fraud over three years involving the same parties satisfies “pattern”

requirement); D.C. Circuit: Pyramid Securities, Ltd. v. International Bank, 726 F. Supp. 1377, 1382, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 7396 (D.D.C. 1989), decision aff'd, 924 F.2d 1114, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7669, 18 Fed.

R. Serv. 3d 909 (D.C. Cir. 1991) (Single scheme lasting three months and involving a single victim is insufficient.).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 4

(“Enterprise”)

Under RICO, the government also must prove as an essential element and beyond a reasonable doubt that an

“enterprise” existed. The essence of a RICO charge is not simply that a number of “racketeering” crimes were

allegedly committed. Rather, the essence of a RICO charge is that several persons formed an organization—called

an “enterprise”—for the purpose of committing “racketeering” crimes, and that through this “enterprise” they in fact

committed a pattern of “racketeering” crimes.

Congress defined “enterprise” to include “any union or group of individuals associated in fact,” but not having a legally

recognized existence in the way that a corporation has a legally recognized existence. For purposes of this case, moreover,

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

I instruct you that any corporation, standing alone, could not be an “enterprise.” The government alleges that the

defendants formed an “enterprise” consisting of a group of people and companies associated together for a common

purpose of engaging in a course of conduct. To prove the existence of this type of “enterprise,” the government must

prove beyond a reasonable doubt three things:

1) That the defendants had a common purpose;

2) that the defendants had an ongoing formal or informal organizational structure; and

3) that the defendants had personnel who functioned as a continuing unit.

This proof must be in the form of evidence separate and apart from the pattern of racketeering activities in which the

“enterprise” allegedly engages.

To satisfy the “ongoing organization” requirement, the government must prove that some sort of structure or process

existed among the defendants for making decisions. In other words, the government must prove that the defendants had

some mechanism for controlling and directing the affairs of the group on an on-going, rather than on a case-by-case basis.

Regarding the requirement that a RICO “enterprise” have personnel who function as a “continuing unit,” this requires

that each person perform a recognized role in the “enterprise,” which furthers the activities of the organization. These

roles must continue to exist over time—that is, there must always be roles such as those found in a Mafia family, where

the identity of the mob members may change from time to time, but the various roles which the old and new individuals

perform remain the same. However, if an entirely new set of people begin to operate the ring, it is not the same enterprise

as it was before.

And, as I said, an enterprise is not the same thing as the “pattern of racketeering activity” in which it allegedly engages.

In other words, the word “enterprise,” when used in ordinary conversation, means an undertaking or project or a unit of

organization established to perform some task. However, under RICO, an enterprise means something special. A RICO

“enterprise” cannot simply be the undertaking of the acts of racketeering; neither can it be the minimal association which

always surrounds such acts.

Rather, a RICO “enterprise” might be demonstrated by proof that a group has an organizational pattern or system of

authority beyond what was necessary to perpetrate the alleged “racketeering” crimes. In other words, if you eliminate the

predicate acts, the evidence must still show the on-going structure engaging in transactions and functions. The command

system of a Mafia family is an example of this type of structure.

Any two criminal acts committed by the same people will necessarily be surrounded by some degree of organization,

and no two individuals will ever jointly perpetrate a crime without at least some degree of association apart from the

commission of the crime itself. Thus, unless there is proof of some structure separate from the racketeering activity and

distinct from the level of organization that necessarily exists when two crimes are committed by the same people, the

government has failed to prove the enterprise element.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

The ties between the individual associates that are implied by the concepts of continuity, unity, shared purpose, and

identifiable structure, operate to guard against the danger that guilty will be adjudged solely by virtue of association.

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583–584, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 2528–29, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH)

P 6100 (1981). U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 660, (8th Cir. 1982) (rejected by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R.

Evid. Serv. 1350 (1st Cir. 2001)). U.S. v. Griffin, 660 F.2d 996, 1000 (4th Cir. 1981). U.S. v. Anderson, 626 F.2d 1358,

1372, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 581 (8th Cir. 1980). U.S. v. Lemm, 680 F.2d 1193, 1198, 10 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1185 (8th Cir.

1982). U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1331 n.16 (5th Cir. 1983). U.S. v. Riccobene, 709 F.2d 214, 221–222, 13 Fed. R.

Evid. Serv. 564 (3d Cir. 1983). Bennett v. Berg, 685 F.2d 1053, 1060, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir.

1982), on reh'g, 710 F.2d 1361, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir. 1983) (rejected by, Virden v. Graphics

One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137 (C.D. Cal.

1985)). U.S. v. Phillips, 664 F.2d 971, 1012, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 970 (5th Cir. 1981). 18 U.S.C.A. § 1961(4). Enterprise

Need Not Have an Existence Separate From the Pattern of Racketeering Activity (Majority View). U.S. v. Hewes, 729

F.2d 1302, 1310–11, 15 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1075 (11th Cir. 1984). U.S. v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 898 (5th Cir. 1978). U.S.

v. Zielie, 734 F.2d 1447, 15 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1928 (11th Cir. 1984). U.S. v. Tille, 729 F.2d 615, 626, 15 Fed. R. Evid.

Serv. 597 (9th Cir. 1984) (proof of association with illegal activities is sufficient).

For example, the Eighth Circuit's view of the scope of RICO in U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 665 (8th Cir. 1982) (rejected

by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1350 (1st Cir. 2001)), differs from the Fifth Circuit's observation

in U.S. v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 896–900 (5th Cir. 1978), that RICO reaches any group of individuals “whose association,

however loose or informal, furnishes a vehicle for the commission of two or more predicate crimes.” In U.S. v. Diecidue,

603 F.2d 535, 545, 4 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1294 (5th Cir. 1979) the Fifth Circuit expressly rejected the argument that

an “enterprise” had to possess an existence separable from the “pattern of racketeering activity” to which some or all

of its members ultimately resort. The fact that the Eighth Circuit's narrower view of the scope of RICO differed from

the Fifth Circuit's position was recognized by the Eighth Circuit twice: in U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 661 (8th Cir.

1982) (rejected by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1350 (1st Cir. 2001)), where that Court expressed

“grave doubts” as to the propriety of decisions such as Elliott; and in Bledsoe's predecessor, U.S. v. Anderson, 626 F.2d

1358, 1372, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 581 (8th Cir. 1980). The Eighth Circuit later determined that the Supreme Court in

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 5828, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100

(1981), did not require abandoning its view of what must be proved for a RICO conviction, finding solace in the Supreme

Court's comment that in order to secure a conviction under RICO, the government must prove both the existence of an

“enterprise” and the connected “pattern of racketeering activity,” and that the existence of an “enterprise” at all times

remains a “separate element which must be proved by the Government.” U.S. v. Lemm, 680 F.2d 1193, 1198, 10 Fed. R.

Evid. Serv. 1185 (8th Cir. 1982). What the Eighth Circuit ignored, however, was language in Turkette on the same page

giving recognition to situations where proof of the “enterprise” and proof of the “pattern of racketeering activity” might

coalesce. The Eleventh Circuit, which deems Elliott to serve as binding precedent, has examined that decision in light of

Turkette and has held that the precedential value of Elliott has not diminished as a result of Turkette. U.S. v. Cagnina,

697 F.2d 915, 920–921, 12 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 492 (11th Cir. 1983) (rejected by, In re National Mortg. Equity Corp.

Mortg. Pool Certificates Securities Litigation, 636 F. Supp. 1138, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6570 (C.D. Cal.

1986)). Other appellate courts agree. U.S. v. Qaoud, 777 F.2d 1105, 1114–1116 (6th Cir. 1985); U.S. v. Mazzei, 700 F.2d

85, 89–90 (2d Cir. 1983). No other court sides with the Eighth Circuit. The Fifth Circuit has not been called upon to decide

whether the Eighth Circuit is correct and whether Turkette has sapped Elliott and Diecidue of their precedential value.

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1340 (5th Cir. 1983). In a recent decision, the court recognized that an association in fact

enterprise must be more than a “summation of predicate acts.” It must have an existence that can be “defined” apart

from the commission of the predicate acts.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 8

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

Ocean Energy II, Inc. v. Alexander & Alexander, Inc., 868 F.2d 740, 748–749, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7200

(5th Cir. 1989). Enterprise Must Have Existence Entirely Independent of Racketeering Activity

(Minority View):

U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 659–66 (8th Cir. 1982) (rejected by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R. Evid. Serv.

1350 (1st Cir. 2001)) (RICO requires proof of the existence of a definite association-in-fact “enterprise” with a structure

separate from the “racketeering activity[.]”).

U.S. v. Anderson, 626 F.2d 1358, 1362–72, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 581 (8th Cir. 1980).

U.S. v. Mazzei, 700 F.2d 85, 89–90 (2d Cir. 1983). Bennett v. Berg, 685 F.2d 1053, 1060, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir. 1982), on reh'g, 710 F.2d 1361, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir. 1983) (rejected

by, Virden v. Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 6137 (C.D. Cal. 1985)).

Atlas Pile Driving Co. v. DiCon Financial Co., 886 F.2d 986, 993–95, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7304 (8th

Cir. 1989) (Association-in-fact enterprise comprised entirely of legitimate businesses possessed an ascertainable structure

distinct from the alleged racketeering activity.).

Compromise View: U.S. v. Riccobene, 709 F.2d 214, 221–222, 13 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 564 (3d Cir. 1983) (the issues of

ongoing organization, continuing membership, withdrawal and separate existence are fact issues for the jury).

Proof of Existance of Enterprise:

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 2528, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100

(1981).

U.S. v. Phillips, 664 F.2d 971, 1011, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 970 (5th Cir. 1981).

U.S. v. Bascaro, 742 F.2d 1335, 1362 (11th Cir. 1984) (abrogated by, U.S. v. Lewis, 492 F.3d 1219 (11th Cir. 2007)).

U.S. v. Hartley, 678 F.2d 961, 999, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 128 (11th Cir. 1982) (abrogated by, U.S. v. Goldin Industries,

Inc., 219 F.3d 1268, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 9914 (11th Cir. 2000)).

U.S. v. Stratton, 649 F.2d 1066, 1075 (5th Cir. 1981). If the plaintiff, however, pleads one specific type of “enterprise,”

facts must support that existence. Otherwise, there is a fatal variance.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 9

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 660 (8th Cir. 1982) (rejected by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1350

(1st Cir. 2001)).

Ocean Energy II, Inc. v. Alexander & Alexander, Inc., 868 F.2d 740, 748–49, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7200

(5th Cir. 1989) (When individuals associate to commit multiple criminal acts their relationship gains an “ongoing nature”

and thus an association-in-fact.).

Atlas Pile Driving Co. v. DiCon Financial Co., 886 F.2d 986, 995–96, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7304 (8th

Cir. 1989).

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1340 (5th Cir. 1983).

Definition of Enterprise:

18 U.S.C.A. § 1961(4). The term “enterprise” encompasses both legitimate or illegitimate “enterprises.”

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583–584, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 2528–29, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH)

P 6100 (1981).

U.S. v. Ruggiero, 726 F.2d 913, 923, 14 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1484 (2d Cir. 1984) (abrogated by, Salinas v. U.S., 522 U.S.

52, 118 S. Ct. 469, 139 L. Ed. 2d 352, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 9382 (1997))).

U.S. v. Lemm, 680 F.2d 1193, 1198, 10 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1185 (8th Cir. 1982).

U.S. v. Thevis, 665 F.2d 616, 626, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1025 (5th Cir. 1982).

U.S. v. Sutton, 642 F.2d 1001, 1006–1009 (6th Cir. 1980) (rejected by, U.S. v. Davis, 793 F.2d 246 (10th Cir. 1986)) and

(rejected by, U.S. v. Calabrese, 825 F.2d 1342 (9th Cir. 1987)).

U.S. v. Rone, 598 F.2d 564, 568–569 (9th Cir. 1979).

U.S. v. Swiderski, 593 F.2d 1246 (D.C. Cir. 1978).

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322 (5th Cir. 1983).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 5

(“Mens Rea”)

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 10

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

Participation in the enterprise's affairs, if any, has to be knowing and willful, in addition to the willful commission of the

predicate offenses. Hence, even if you find that defendant willfully committed at least two “racketeering” offenses, you

must further find that he knowingly and willfully joined and participated in the enterprise's affairs.

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 6

(“Associated With”)

As I said there is no guilt by association under RICO. Thus, as another essential element of a RICO charge, the

government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that each defendant knew something about his co-defendant's

racketeering activities committed through the enterprise.

U.S. v. Martino, 648 F.2d 367, 394 (5th Cir. 1981), on reconsideration in part, 650 F.2d 651 (5th Cir. 1981) and on reh'g,

681 F.2d 952 (5th Cir. 1982), judgment aff'd, 464 U.S. 16, 104 S. Ct. 296, 78 L. Ed. 2d 17, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 6100 (1983), on reconsideration in part, 650 F.2d 651 (5th Cir. 1981) and on reh'g, 681 F.2d 952 (5th Cir. 1982),

judgment aff'd, 464 U.S. 16, 104 S. Ct. 296, 78 L. Ed. 2d 17, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (1983).

U.S. v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 903 (5th Cir. 1978).

U.S. v. Bledsoe, 674 F.2d 647, 659–66 (8th Cir. 1982) (rejected by, U.S. v. Patrick, 248 F.3d 11, 56 Fed. R. Evid. Serv.

1350 (1st Cir. 2001)).

U.S. v. Anderson, 626 F.2d 1358, 1362–72, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 581 (8th Cir. 1980).

U.S. v. Mazzei, 700 F.2d 85, 89–90 (2d Cir. 1983).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 7

(“Conduct or Participation in the Enterprise's Affairs”)

For the same reasons, defendant's conduct or participation in the enterprise's affairs must be related to the management

of the affairs of the enterprise. You may not infer from a defendant's status as an officer, shareholder and/or employee

that he used any facility to promote, manage, establish, carry on, or facilitate the promotion, management, establishment,

or carrying on of the enterprise. Hence, unless a defendant participated in the operation or management of the enterprise

itself, the requisite degree of participation in the conduct of the affairs of the enterprise will be deficient.

U.S. v. Truglio, 731 F.2d 1123, 1132 (4th Cir. 1984) (overruled by, U.S. v. Burgos, 94 F.3d 849 (4th Cir. 1996))).

Bennett v. Berg, 710 F.2d 1361, 1364, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir. 1983) (rejected by, Virden v.

Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137

(C.D. Cal. 1985)).

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 11

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

U.S. v. Mandel, 591 F.2d 1347, 1375, 5 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 133 (4th Cir. 1979), on reh'g, 602 F.2d 653 (4th Cir. 1979)

and (rejected by, Virden v. Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus.

Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137 (C.D. Cal. 1985)).

U.S. v. Kaye, 586 F. Supp. 1395, 1400 (N.D. Ill. 1984) (rejected by, Virden v. Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O.

Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137 (C.D. Cal. 1985)).

Participation in Operation or Management:

Bennett v. Berg, 710 F.2d 1361, 1364, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100 (8th Cir. 1983) (rejected by, Virden v.

Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137

(C.D. Cal. 1985)); U.S. v. Mandel, 591 F.2d 1347, 1375, 5 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 133 (4th Cir. 1979), on reh'g, 602 F.2d

653 (4th Cir. 1979) and (rejected by, Virden v. Graphics One, 623 F. Supp. 1417, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

6128, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6137 (C.D. Cal. 1985)) (operation or management of “enterprise” required);

Occupational-Urgent Care Health Systems, Inc. v. Sutro & Co., Inc., 711 F. Supp. 1016, 1025–26, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 7235 (E.D. Cal. 1989); Vista Co. v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., 725 F. Supp. 1286, 1297–98,

R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7388 (S.D. N.Y. 1989) (Partnership's claim under 1962(c) had been met by allegations

that the Defendant was in a position to commit the predicate acts solely by virtue of his involvement in the enterprise

operation or management of that enterprise.).

Conduct Facilitated by Association with the Enterprise: U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1341 (5th Cir. 1983) (defendant's

position in “enterprise” permitted him to make facilities and funds available); U.S. v. LeRoy, 687 F.2d 610, 617, 111

L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2238, 95 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 13754 (2d Cir. 1982) (position in union enabled defendant to receive

illegal payments); U.S. v. Kovic, 684 F.2d 512, 516–17, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 854 (7th Cir. 1982); Yellow Bus Lines,

Inc. v. Drivers, Chauffeurs & Helpers Local Union 639, 883 F.2d 132, 142–143, 132 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2164, 113 Lab.

Cas. (CCH) P 11530, 113 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 11669, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7286, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 7364 (D.C. Cir. 1989), on reh'g in part, 913 F.2d 948, 135 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2177, 116 Lab. Cas. (CCH)

P 10275, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 7554 (D.C. Cir. 1990).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 8

(“Interstate Commerce”)

Under RICO, the government also must prove as an essential element and beyond a reasonable doubt that an enterprise

engaged in or performed activities which affected interstate commerce. Therefore, if you find that an enterprise existed

as alleged by the government, then you must also decide whether that enterprise engaged in or had any effect upon

interstate commerce. Interstate commerce means commerce between the several states.

With respect to the requirement that the “enterprise” was engaged in, or that its activities affected, interstate commerce—

the plaintiff contends that in conducting the affairs of the enterprise the Defendants utilized interstate communications

facilities by causing the transmission of funds by mail or by wire in interstate commerce from one state to another. You

are instructed that if you do not find beyond a reasonable doubt that these transactions or events occurred, and that

they occurred in, or as a direct result of, the conduct of the affairs of the alleged enterprise, the required effect upon

interstate commerce has not been established.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 12

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

R.A.G.S. Couture, Inc. v. Hyatt, 774 F.2d 1350, 1353, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6101 (5th Cir. 1985) (rejected

by, Lawaetz v. Bank of Nova Scotia, 23 V.I. 132, 653 F. Supp. 1278 (D.V.I. 1987)).

U.S. v. Dickens, 695 F.2d 765, 781 (3d Cir. 1982).

U.S. v. Rone, 598 F.2d 564, 573 (9th Cir. 1979).

U.S. v. Stratton, 649 F.2d 1066, 1075 (5th Cir. 1981).

U.S. v. Nerone, 563 F.2d 836 (7th Cir. 1977).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 9

(“Racketeering Acts — General”)

The government alleges that these defendants engaged in a pattern of racketeering activity by committing two or more

acts of mail fraud, receipt of stolen goods in foreign commerce, or Travel Act offenses, in violation of Title 18 of the

United States Code, and commercial bribery, in violation of (state) law.

Before you could find that any of these defendants committed any act of racketeering activity, you would have to find

beyond a reasonable doubt that such defendant committed each essential element of the particular criminal act that

is charged. I will now instruct you as to the essential elements of each criminal act that the government charges these

defendants committed.

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 10

(“Racketeering Acts ___ and ___”)

The first type of “racketeering” act that the government charges these defendants with committing is mail fraud. 18

U.S.C.A. § 1341, provides in part that:

“Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property

by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises … for the purpose of executing such scheme or

artifice or attempting so to do, places in any post office or authorized depository for mail matter, any matter or thing

whatever to be sent or delivered by the Post Office Department [shall be guilty of an offense against the laws of the

United States.]”

In order to establish that a Defendant is guilty of mail fraud, the Government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that:

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 13

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

1. The Defendant willfully and knowingly devised a scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property

by means of false pretenses, representations or promises, and

2. The Defendant used the United States Postal Service by mailing, or by causing to be mailed, some matter or thing for

the purpose of executing the scheme to defraud.

The words “scheme” and “artifice” include any plan or course of action intended to deceive others, and to obtain, by

false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, money or property from persons so deceived.

A statement or representation is “false” or “fraudulent” within the meaning of this statute if it relates to a material fact

and is known to be untrue or is made with reckless indifference as to its truth or falsity, and is made or caused to be

made with intent to defraud. A statement or representation may also be “false” or “fraudulent” when it constitutes a half

truth, or effectively conceals a material fact, with intent to defraud. A “material fact” is a fact that would be important

to a reasonable person in deciding whether to engage or not engage in a particular transaction.

To act with “intent to defraud” means to act knowingly and with the specific intent to deceive, ordinarily for the purpose

of causing some financial loss to another or bringing about some financial gain to one's self.

What must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt is that the accused knowingly and willfully devised or intended to

devise a scheme to defraud substantially the same as the one alleged in the indictment; and that the use of the U.S. mail

was closely related to the scheme in that the accused either mailed something or caused it to be mailed in an attempt to

execute or carry out the scheme. To “cause” the mails to be used is to do an act with knowledge that the use of the mails

will follow in the ordinary course of business or where such can be reasonably foreseen.

Each separate use of the mails in furtherance of a scheme to defraud constitutes a separate offense.

Pattern Jury Charges

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 11

(“Racketeering Act ___”)

The next “racketeering” act that the government charges these defendants with committing is receiving stolen goods in

foreign commerce. 18 U.S.C.A. § 2315, provides in part as follows:

“Whoever receives, conceals, stores, or sells, goods or merchandise, of the value of $5,000.00 or more … moving as, or

which are a part of … foreign commerce, knowing the same to have been stolen …[shall be guilty of an offense against

the United States].”

There are four essential elements which must be proved beyond reasonable doubt in order to establish the offense

proscribed by this law:

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 14

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

First: That the Defendant received or concealed or stored or sold items of stolen property as described in the indictment;

Second: That such items were moving as, or constituted a part of, foreign commerce;

Third: That such items had a value in excess of $5,000.00; and

Fourth: That the Defendant acted knowingly and willfully.

The indictment alleges that the Defendant received, concealed, stored, and sold certain stolen property. The statute

specifies these several, alternative ways in which an offense can be committed, and it is not necessary for the Government

to prove that all of such acts were in fact committed. The Government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the

Defendant either received, concealed, stored, or sold the stolen property; and, in order to find the defendant liable you

must agree unanimously upon the way or manner in which the offense was committed.

Also, in order to commit the offense charged a Defendant must know the property had been stolen, but he need not

know that it was moving as, or constituted a part of, foreign commerce. It is sufficient if the property has recently moved

from one country into another country as a result of a transaction or a series of related transactions which have not been

fully completed or consummated at the time of the act or acts alleged in the indictment.

The word “value” means the face, par, or market value, or cost or price, either wholesale or retail, whichever is greater.

U.S. v. Gipson, 553 F.2d 453, 458–59 (5th Cir. 1977) (rejected by, Rice v. State, 311 Md. 116, 532 A.2d 1357, 75 A.L.R.4th

73 (1987)).

Pattern Jury Instructions

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 12

(“Racketeering Act ___”)

The next “racketeering act that the government charges these defendants with committing is “commercial bribery” in

violation of (state) law. Section ___ of the ___ Penal Code, as in effect at the time the government charges it was violated,

provided in part that:

(b) A person who is a fiduciary commits an offense if he intentionally or knowingly solicits, accepts, or agrees to accept

any benefit as consideration for: (1) violating a duty to a beneficiary; or (2) otherwise causing harm to a beneficiary by

act or ommission. (c) A person commits an offense if he offers, confers, or agrees to confer any benefit the acceptance

of which is an offense under Subsection (b) of this section.

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 15

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

A “fiduciary” is an officer, director, partner, manager or other participant in the direction of the affairs of a corporation

or an association, or an agent or employee. A “beneficiary” is a person on whose behalf the “fiduciary” is acting.

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 13

(“Racketeering Act Number ___”)

The next “racketeering” act that the government charges these defendants with committing is a violation of the federal

Travel Act. 18 U.S.C.A. § 1952(a)(3) provides that:

“Whoever travels in interstate … commerce or uses any facility in interstate commerce … with intent to—

(3) … promote, manage, establish, carry on, or facilitate the promotion, management, establishment or carrying on of

any unlawful activity [and thereafter performs or attempts to perform any act to promote, manage, establish or carry on

such unlawful activity] [shall be guilty of an offense against the United States].”

There are three essential elements which must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt in order to establish the offense

proscribed by this law:

First: That the Defendant traveled in interstate commerce on or about the time, and between the places, charged in the

indictment;

Second: That the Defendant engaged in such travel and with the specific intent to promote, manage, establish or carry

on an “unlawful activity”, as hereafter defined; and

Third: That the Defendant thereafter knowingly and willfully committed an act to promote, manage, establish or carry

on such “unlawful activity.”

The term “interstate commerce” means transportation or movement between one state and another state, and while it

must be proved that the Defendant traveled in interstate commerce with the specific intent to promote, manage, establish

or carry on an “unlawful activity,” it need not be proved that such purpose was the only reason or motive prompting

the travel.

The term “unlawful activity” includes commercial bribery in violation of the laws of the state in which it is committed.

Pattern Jury Instructions

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 14

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 16

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

(“Other Racketeering Acts”)

The government charges that other defendants—but not defendants X, Y, & Z—committed one other type of

“racketeering” act. Specifically, the government charges that these other defendants violated the statute against

obstruction of justice. I instruct you that the government does not allege that defendants X, Y, & Z violated RICO in this

way. Therefore, you may not consider any evidence regarding charges of obstruction of justice as evidence of a RICO

violation by these defendants.

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 15

(“Unanimous Verdict”)

You are further instructed that you must unanimously agree concerning each Defendant under consideration as to which

of the two predicate offenses he is alleged to have committed. It would not be sufficient if some of the jurors should

find that a Defendant committed two of the predicate offenses while the remaining jurors found that he committed two

different offenses. You must all agree that the same defendant committed the same two predicate offenses in order to

find a Defendant liable for RICO.

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1345 (5th Cir. 1983).

U.S. v. Ruggiero, 726 F.2d 913, 921–923, 14 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1484 (2d Cir. 1984) (abrogated by, Salinas v. U.S., 522

U.S. 52, 118 S. Ct. 469, 139 L. Ed. 2d 352, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 9382 (1997))).

U.S. v. Ballard, 663 F.2d 534, 554 (5th Cir. 1981), reh'g denied and opinion modified, 680 F.2d 352 (5th Cir. 1982).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 16

(“Statute of Limitations”)

No criminal action shall be maintained unless brought within a specified period.

One of the predicate acts of racketeering, if any you so find, must have been personally committed within five years of

the date of the indictment. The indictment was filed on [date of indictment]. The statute of limitations must be satisfied

as to each defendant.

If you find that a defendant personally committed at least two predicate acts, but you further find that he personally

committed those acts, you so find, before ___, then that defendant has no criminal responsibility for the RICO offense

in Count ___.

U.S. v. Walsh, 700 F.2d 846, 851, 69 A.L.R. Fed. 233 (2d Cir. 1983).

U.S. v. Bethea, 672 F.2d 407, 419 (5th Cir. 1982).

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 17

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 17

(“Nexus Between Enterprise, Defendant, and Racketeering Activity”)

RICO criminalizes the conduct of an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activities and not merely the

defendant engaging in racketeering activity. Therefore, there must be a nexus—a connection—between the enterprise,

the defendant, and the pattern of racketeering activity.

The mere fact that a defendant works for a legitimate business and commits racketeering acts while on the business

premises does not establish that the affairs of the enterprise have been conducted through a pattern of racketeering

activity. Racketeering activity alone does not violate RICO. Rather, to violate RICO, the illegal activity must advance

the affairs of the enterprise. Acts performed should be necessary and helpful to the operation of the enterprise. To find

that any defendant has conducted or participated in the affairs of the enterprise “through” a pattern of racketeering

activity, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt each of the following facts:

1. That, beyond a reasonable doubt, the party accused of violating RICO has in fact committed the racketeering acts

alleged;

2. That the party accused of violating RICO had a position in the enterprise which facilitated, or played an essential role

in, the commission of those racketeering acts; and

3. That the racketeering acts had some effect upon the enterprise. You may find such an effect if you find that the

enterprise's affairs were advanced or furthered by the pattern of racketeering activity. This is another way of saying

that the pattern of racketeering activity must be related to the affairs of the enterprise.

However, a defendant's mere association with a lawful enterprise whose affairs are conducted through a pattern of

racketeering activity in which he is not personally engaged does not establish his guilt under RICO.

U.S. v. Phillips, 664 F.2d 971, 1011, 1014, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 970 (5th Cir. 1981) (gravaman of RICO offense is conduct

of an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity).

U.S. v. Martino, 648 F.2d 367, 381–382 (5th Cir. 1981), on reconsideration in part, 650 F.2d 651 (5th Cir. 1981) and on

reh'g, 681 F.2d 952 (5th Cir. 1982), judgment aff'd, 464 U.S. 16, 104 S. Ct. 296, 78 L. Ed. 2d 17, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp.

Guide (CCH) P 6100 (1983) (RICO proscribes the furthering of the enterprise, not the predicate acts; acts performed

should be “necessary and helpful to the operation of the enterprise.).

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1331–1332 (5th Cir. 1983).

U.S. v. Barber, 668 F.2d 778, 10 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 258 (4th Cir. 1982).

U.S. v. Erwin, 793 F.2d 656, 671 (5th Cir. 1986).

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 18

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

U.S. v. Manzella, 782 F.2d 533, 538, 20 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 196 (5th Cir. 1986).

U.S. v. Mitchell, 777 F.2d 248, 258 (5th Cir. 1985) (racketeering act must “be conducted through a defined enterprise”).

U.S. v. Welch, 656 F.2d 1039, 1060–61 (5th Cir. 1981) (acts must be “related to” the affairs of enterprise).

U.S. v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576, 583, 101 S. Ct. 2524, 2528–29, 69 L. Ed. 2d 246, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

6100 (1981) (activities must be “connected” to enterprise).

Haroco, Inc. v. American Nat. Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago, 747 F.2d 384, 400, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

6100 (7th Cir. 1984), decision aff'd, 473 U.S. 606, 105 S. Ct. 3291, 87 L. Ed. 2d 437, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 92087,

R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6100, 1985-2 Trade Cas. (CCH) ¶ 66667 (1985).

Alcorn County, Miss. v. U.S. Interstate Supplies, Inc., 731 F.2d 1160, 1168, 39 Fed. R. Serv. 2d 171, 76 A.L.R. Fed. 181

(5th Cir. 1984) (abrogated by, U.S. v. Cooper, 135 F.3d 960 (5th Cir. 1998)).

U.S. v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 899 n.23 (5th Cir. 1978).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 18

(“Withdrawal”)

As you have been instructed, an enterprise requires an ongoing organization and continuing membership.

So, if a Defendant becomes a member of an enterprise but later changes his mind and withdraws before he has personally

committed any racketeering acts as previously defined, then the crime was not complete at that time, and the Defendant

who withdrew cannot be convicted—he would be not guilty of the alleged RICO offense.

U.S. v. Riccobene, 709 F.2d 214, 221–222, 13 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 564 (3d Cir. 1983).

U.S. v. Cauble, 706 F.2d 1322, 1333 (5th Cir. 1983).

U.S. v. Winter, 663 F.2d 1120, 1136 (1st Cir. 1981) (abrogated by, Salinas v. U.S., 522 U.S. 52, 118 S. Ct. 469, 139 L.

Ed. 2d 352, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 9382 (1997)).

U.S. v. Sutherland, 656 F.2d 1181, 1186–87 n.4, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 278 (5th Cir. 1981).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 19

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 19

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

(“Multiple Enterprises”)

The government charges that the defendants formed themselves into an illegal group for purposes of committing

“racketeering” crimes. In RICO Count ___, this allegedly illegal group is called a RICO “enterprise.”

You may find from the evidence, however, that no such “enterprise,” as alleged by the government, existed at all.

You also may find from the evidence that the defendants formed themselves into different groups—that is, different

“enterprises”—than the enterprise alleged in the indictment. If you find that no “enterprise” existed at all, or that there

existed different “enterprises” than the one alleged in the indictment, then you must find the defendants not guilty.

All of this is so because proof of several separate enterprises is not proof of the single, overall RICO enterprise charged in

the indictment. What you must do, therefore, is determine whether the single, overall enterprise charged in the indictment

existed. If you find that no such single, overall enterprise existed, then you must find the defendants not guilty. In other

words, to find a defendant guilty, you must find that he was a member of precisely the same enterprise charged in the

indictment, and not some other, separate enterprise. However, if you find that the single, overall enterprise existed, but

that certain defendants were not members of that enterprise, then you must find those defendants not guilty.

To establish a single, overall enterprise, the government must prove a single agreement to accomplish an overall objective

or goal. The government also must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the nature of the illegal enterprise was such

that each defendant must necessarily have known that others were participating in the same illegal scheme. On this point,

therefore, you must find a defendant not guilty unless the government proves that the defendant knew (1) that he was

directly involved in an enterprise whose purpose was to profit from crime, (2) that he knew that the enterprise was larger

than his own role in it, and (3) that others, unknown to him, were participating in the illegal scheme.

That is, the participants in an enterprise must have known of the others' illegal activities and, indeed, must have joined

with one another in furtherance of the illegal activities. Each defendant must have realized that the enterprise extended

beyond his individual role. Moreover, a defendant is not responsible for the acts of the others in the enterprise that go

beyond the goals of the enterprise as that defendant understands them.

The scope of an enterprise is judged by five factors: (1) the time during which it existed; (2) the persons who participated

in the group; (3) the statutory offenses charged in the indictment; (4) the nature and scope of the allegedly illegal acts

that were committed; and (5) the locations where those events took place. Each of these factors must point toward a

single enterprise. That is, there must be similarity of time, persons, places, offenses charged, and acts undertaken before

you could find that the alleged events are tied together into a single enterprise.

For example, there are three different corporations that are defendants. The government charges that the three companies

and their employees formed one overall illegal enterprise. If you find that each company and its employees acted illegally,

but that each company and its employees did so separately and apart from each other, then you must find the defendants

not guilty, because your findings would be different from the charges brought by the government.

U.S. v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 902–903 (5th Cir. 1978).

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 20

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

U.S. v. Sutherland, 656 F.2d 1181, 1191–1195, 9 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 278 (5th Cir. 1981).

U.S. v. Erwin, 793 F.2d 656, 671 (5th Cir. 1986).

U.S. v. Brooklier, 685 F.2d 1208, 1222, 11 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 703 (9th Cir. 1982).

U.S. v. Starnes, 644 F.2d 673, 677–78 (7th Cir. 1981).

Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., Inc., 473 U.S. 479, 496, 105 S. Ct. 3292, 87 L. Ed. 2d 346, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P

92086 (1985).

U.S. v. Bright, 630 F.2d 804, 834–835, 6 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 550 (5th Cir. 1980).

U.S. v. Stratton, 649 F.2d 1066, 1073 n.8 (5th Cir. 1981).

U.S. v. Mitchell, 777 F.2d 248, 260 (5th Cir. 1985).

U.S. v. Nerone, 563 F.2d 836, 851–852 (7th Cir. 1977).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 20

(“Proof of Seven Facts”)

In order to establish that the Defendants, or any of them, committed the offense charged in that a particular, there are

seven specific facts which the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt:

First: That the defendant was a “person” as defined in these instructions;

Second: That the defendant was “associated with” an “enterprise” as both terms are defined in these instructions;

Third: That the defendant knowingly and willfully personally committed at least two of the predicate offenses previously

specified within ten years of each other, one of which must have occurred after ___;

Fourth: That the two predicate offenses allegedly committed by the defendant were connected with each other by some

common scheme, plan or motive so as to be a pattern of criminal activity and not merely a series of separate, isolated

or disconnected acts;

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 21

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

Fifth: That through the commission of the two or more connected offenses, the defendant “conducted or participated

in the conduct of the enterprise's affairs” as defined in these instructions;

Sixth: That the defendant's conduct or participation in the enterprise's affairs was related to the management or operation

of the affairs of the enterprise; and

Seventh: That the “enterprise” was engaged in, or that its activities affected, “interstate commerce”, as defined in these

instructions.

Pattern Jury Instructions

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 21

(“Liability of Corporations”)

Three of the defendants in this case are corporations. Because they are lifeless entities, whose existence is recognized only

by the law, corporations cannot be found guilty of any crime under the same standards that apply to the human officers

and employees of a corporation. Instead, special standards apply to criminal charges brought against corporations.

In your consideration of the charges against the corporations that are defendants here, you should first consider the

evidence presented as to the charges against the officers and the employees of the corporations. If you find that the

officers and employees of the corporations are not guilty of any offense, then you must find the corporations for whom

the officers and employees worked not guilty as well.

However, if you find any officer or employee of one of the corporations guilty of an offense, then you must examine

the evidence with respect to two issues that affect the responsibility of the corporation for the acts of its officers and

employees:

First: At the time that any officer or employee acted illegally, was he acting within the scope of his employment. That is

to say, was the employee then performing a function of the type that he was supposed to perform at his job.

Second: At the time that any officer or employee acted illegally, was he acting with the purpose to benefit the corporation

for which he worked, as opposed to a purpose to benefit only himself or others. If the answer to either of those two

questions is “no,” then you must find the defendant corporations not guilty, no matter what verdict you reach with

respect to the officers and employees of the corporations. U.S. v. Bi-Co Pavers, Inc., 741 F.2d 730, 737, 1984-2 Trade

Cas. (CCH) ¶ 66198, 16 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 421 (5th Cir. 1984). Standard Oil Co. of Tex. v. U.S., 307 F.2d 120, 125

(5th Cir. 1962).

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 22

(“RICO — Conspiracy”)

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 22

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

The government also charges that the Defendants knowingly and willfully conspired to violate RICO. The alleged

conspiracy is a separate crime or offense in violation of RICO. In that regard, you must find beyond a reasonable doubt

the same seven specific facts listed in instruction number [Instruction Number], page [Page], (RICO substantive), except

that the government need not prove that two or more substantive crimes were actually committed; what the government

must prove is that the defendant personally agreed to commit two or more substantive crimes.

Pattern Jury Instructions

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 23

(“Definition of Conspiracy”)

Under the law a “conspiracy” is a combination or agreement of two or more persons to join together to attempt to

commit an offense which would be in violation of RICO. It is a kind of “partnership in criminal purposes” in which

each member becomes the agent of every other member with the objective of conducting or participating in the affairs of

the enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity. U.S. v. Sutherland, 656 F.2d 1181, 1191–1195, 9 Fed. R. Evid.

Serv. 278 (5th Cir. 1981). Pattern Jury Instructions

RICO INSTRUCTION NO. 24

(“Cautionary Instruction Conspiracy—Hearsay”)

With respect to the conspiracy offense as alleged in the indictment you should first determine, from all of the testimony

and evidence in the case, whether or not the conspiracy existed as charged in the indictment, or whether there were

multiple conspiracies as defined in instruction number [Instruction Number] on page [Page]. If you conclude that a

conspiracy did exist as alleged in the indictment, you should next determine whether the defendant under consideration

willfully became a member of such conspiracy. In determining whether a defendant was a member of the alleged

conspiracy, however, the jury should consider only that evidence, if any, pertaining to his own acts and statements. He

cannot be bound by the acts or statements of other alleged participants until it is established, beyond a reasonable doubt,

First, that a conspiracy existed as charged in the indictment; and, Second, from evidence of his own acts and statements,

that the defendant under consideration was one of its members.

On the other hand, if and when it does appear, if it should so appear, beyond a reasonable doubt from the evidence in

the case that a conspiracy did exist as charged in the indictment, and that the defendant under consideration was one

of its members, then the statements and acts knowingly made and done, during the conspiracy and in furtherance of

its objects, by any other proven member of the conspiracy, may be considered as evidence against the defendant under

consideration even though he was not present to hear the statements made or see the acts done.

This is true because, as stated earlier, a conspiracy is a kind of “partnership” under the law so that each member is an

agent of every other member, and each member is bound by or responsible for the acts and statements of every other

member made in pursuance of their unlawful scheme.

For example, during the course of the trial you have heard what are alleged to have been out-of-court declarations

by various defendants that were offered through the testimony of government agents or others. Any admission or

incriminatory statement or declaration made or act done outside of court by one defendant may only be considered

© 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 23

§ 13:31.Criminal jury instructions, 2 White Collar Crime § 13:31 (2d ed.)

as evidence against the defendant making the statement or declaration and may not be considered as evidence against

any other defendant unless you find beyond a reasonable doubt (1) that independent evidence other than the alleged

statement or declaration has been presented that shows that the conspiracy as charged in the indictment existed; (2) that

from independent evidence of his own acts and statements the defendant against whom the statement is offered was

a member of the same conspiracy as charged in the indictment as the defendant/declarant; and (3) that the statement

was made during the course and in furtherance of that conspiracy as charged in the indictment. Because of presumptive

unreliability of co-conspirator's out-of-court statements, a co-conspirator's statement implicating the defendant in an

alleged conspiracy must be corroborated by fairly incriminating evidence. Evidence of wholly innocuous conduct or

statements by the defendant will rarely be sufficiently corroborative of the co-conspirator's statement to constitute proof,

beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant knew of and participated in the conspiracy. Evidence of innocent conduct

does little, if anything, to enhance the reliability of the co-conspirator's statement. A co-conspirator's statement, which is

presumptively unreliable hence inadmissible standing alone, is no more reliable when coupled with evidence of conduct

that is completely consistent with defendant's unawareness of the conspiracy.

Independent evidence separate from the out-of-court declarations must demonstrate the existence of the charged

conspiracy and defendant's membership and participation. Although a defendant's own statements may constitute

independent evidence of membership and participation, you should always consider the character and credibility of the

person who provides the testimony against a defendant. For example, the testimony of an alleged accomplice, and the

testimony of one who provides evidence against a Defendant as an informer for pay or for immunity from punishment or

for personal advantage or vindication, must always be examined and weighed by the jury with greater care and caution

that the testimony of ordinary witnesses. You, the jury, must decide whether the witness' testimony has been affected by