Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Canadian Cordilleran Model For Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Uploaded by

NajidYasser0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views14 pagesA Canadian Cordilleran Model for Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Original Title

A Canadian Cordilleran Model for Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA Canadian Cordilleran Model for Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views14 pagesA Canadian Cordilleran Model For Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Uploaded by

NajidYasserA Canadian Cordilleran Model for Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

‘Ore Deposit Models

A Canadian Cordilleran

Model for Epithermal

Gold-Silver Deposits

‘Andrejs Panteleyev

‘Senior Project Geologist

Geological Branch

‘Mineral Resources Division

British Columbia Ministry of Energy,

‘Mines and Petroleum Resources

Victoria, British Columbia VaV 1X4

Introduction

Discovery of ode gold in 1851 and placer

{Goldin 1857 initiated the fist large-scale

feconomicactvityinBritishColumbiaand

Jed to.a major influx of miners during the

{gold rushes of the mid- and late 1800s.

This explosion of non-native population

necessitated colonial expansion, the

creation of new settlements, develop-

‘ments ofinfrastructure, andprovidedthe

‘economic base for the fledgling colony.

Total gold production to date trom the

Canadian Cordilera (British Columbia

land Yukon) is close to 182 tonnes (38

million ounces), approximately one-third

‘of the amount produced by Ontario.

About 60% of Cordilaran gold comes

from lode deposits; the remainder has

been won from placer workings. Placer

‘goldproductionpeakedin 1900;lodegold

production peaked in 1939 when 18.3

tonnes of gold were produced in British

Columbia. Thereatter, output declined

steadily until the early 1970s when by-

‘Product gold, mainly from porphyry cop-

perminesaswellasmassivesulphideand

‘skarn deposits, became the dominant

source. These accountedtor upto80%ot

theannual3-4tonnesof oldproduction,

Goldwasliberatedininternationalmar-

ketsin 1968fromthefixedpriceof $35US

per ounce setin 1984. Theresultingprice

Increases, culminating in spectacular

price peaksinlate 1979, renewedinterest

in known deposits and enlivened the

uest for new supplies of both gold and

silver. The search for gold has been the

main focus during the 1980s of the min-

ing exploration community, a $100 mil-

lion annual enterprise in the Canadian

Cordillera. One of the primary targets

has been gold-siiver deposits of the

3

“epithermal ype", also known variously

‘as"bonanzaores", "Tertiarytype","pre-

‘ious metal deposits of volcanic asso-

ciation” or “fossil hot spring type”

(Figure 1 and Table 1).

tskur

‘BOUNDARY-GREENWOOD —

‘sHete check van

MAIN pePoStTS.

EPITHERMAL DEPOSITS

CCASSIAR

—canisoo.

BLacKoome

0.

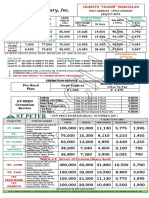

Figure 1 Distrbuonofgolddepostsin BritshColumbiashowingmajorcamps,invcual deposits

‘and areas of recent exploration activity. Unes indeate major ctone-physoeyaphic boundaries.

CCrystatinemetamorphic terranes Coast Plutonic Btn thewestandOmineca Bettinthe east

‘are shown by te hachured pattern.

Epithermal precious metal deposits

are attractive, especially when base

metal prices are depressed, because

they have high unit values of precious

metals with generally low or no base

‘metal content. The deposits commonly

‘occuras small vein systems (less thana

million tonnes in size), but they tend to

have good grades, and many contain

high-grade ore shoots. They provide

‘quick payback at high rates of return on

modest amounts of invested capital.

Consequently epithermal deposits are

particularly attractive to smaller com-

panies that seek financing primarily

from public sources. n addition, major

‘mining companies, with long-term in-

vestment strategies and the ability to

support major capital outlays, seek

larger epithermal prospects suitable for

‘open-pit operations. An example of the

type of superior epithermal deposit that

‘explorationists strive to find is the El

Indio Mine, Chile, which began limited

production in 1979. In its first year of

operation, 12,800 kilograms of gold

were produced from 50,000 tonnes of

direct shipping ore. There remained

70,000 tonnes of similar material con-

taining277 grams goldpertonneaswell

‘as main reserves of 3.2 milion tonnes

with 123 grams gold per tonne, 141

‘orams silver per tonne, and 4.096 cop-

per (Walthier et a, 1982).

Characteristics of Epithermal Deposits

The term "epithermal” was introduced

by Waldemar Lindgren in 1939. Itis part

‘of a genetic classification of ore de-

posits that describes hydrothermal uid

‘sources and depth zonesiin such terms

"and

Epithermal deposits

were considered (Lindgren, 1933,

. 212) tobe formed "by hot ascending

‘waters of uncertain origin, but charged

With igneous emanations. Deposition

‘and concentration (of ore minerals oc-

curs) at slight depth”. He considered

temperatures to range from 60-200°C

under conditions of “moderate” pres-

sure. Lindgren also noted that epither

‘maldepositshave "stikinganalogiesto

those products of the hot springs”

Other workers, such as Buddington

(1935), recognized that temperatures

‘greater than those suggested by

Lindgren were possible in near surface

hydrothermal environments. Soon the

Upper temperature limit for epithermal

deposits was extended to at least

300°C. Use of the term “epithermal”

‘became well entrenchedin North Amer-

jcaand elsewhere during the 1940s and

1950s. Many descriptions of epither-

‘mal-type deposits and districts ac-

cumulated and document the

‘geometry, structural controls and min-

‘eralogical variations of these deposits.

Geoscience Canada Reprint Series 3

Review articles describing “epthermal

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Rocks and MineralsDocument643 pagesRocks and MineralsNajidYasser100% (4)

- MACIG-2016 Geology of AfricaDocument87 pagesMACIG-2016 Geology of AfricaNajidYasserNo ratings yet

- Rocks and Minerals - 1405305940Document224 pagesRocks and Minerals - 1405305940Anyak2014100% (5)

- Minéralisation D'argent D'imiterDocument23 pagesMinéralisation D'argent D'imiterNajidYasserNo ratings yet

- Bentonite de NadorDocument10 pagesBentonite de NadorNajidYasserNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ACF 103 Tutorial 6 Solns Updated 2015Document18 pagesACF 103 Tutorial 6 Solns Updated 2015Carolina SuNo ratings yet

- Finance FunctionDocument10 pagesFinance Functionadmire007No ratings yet

- BFM Project Report in FinanceDocument52 pagesBFM Project Report in FinanceRaunak MotwaniNo ratings yet

- Bank of Africa, Burkina Faso ScamsDocument2 pagesBank of Africa, Burkina Faso ScamsVIJAY KUMAR HEERNo ratings yet

- Fa2 Mock Test 2Document7 pagesFa2 Mock Test 2Sayed Zain ShahNo ratings yet

- Miao Huaxian Vs Crane BankDocument12 pagesMiao Huaxian Vs Crane BankAugustine Idoot ObililNo ratings yet

- TVS Case Study Personal LoanDocument4 pagesTVS Case Study Personal LoanBhavya PopliNo ratings yet

- BMA Demo 2Document28 pagesBMA Demo 2Huế HoàngNo ratings yet

- BilledStatements 4806 16-10-22 18.18Document2 pagesBilledStatements 4806 16-10-22 18.18Harsh NawariaNo ratings yet

- Erste Bank Research Euro 2012Document10 pagesErste Bank Research Euro 2012Wito NadaszkiewiczNo ratings yet

- Landbank Vs PobleteDocument3 pagesLandbank Vs PobletejessapuerinNo ratings yet

- 2017 Undas Pricelist NewDocument1 page2017 Undas Pricelist NewDanica UgayNo ratings yet

- Creditor AbbreviationsDocument8 pagesCreditor AbbreviationsAndrés FlórezNo ratings yet

- Banks' Contact NumbersDocument4 pagesBanks' Contact Numbersfmj_moncanoNo ratings yet

- European Debt Relief Benefits GreeceDocument4 pagesEuropean Debt Relief Benefits GreecethepressprojectNo ratings yet

- Volksbank Presentation PDFDocument8 pagesVolksbank Presentation PDFCIBPNo ratings yet

- Alagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper3Document5 pagesAlagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper3mansoorbariNo ratings yet

- TcodeDocument2 pagesTcodeMere HamsafarNo ratings yet

- IMF and The World Trade Organization SP PDFDocument3 pagesIMF and The World Trade Organization SP PDFRoberto Carlos Cruzado HaroNo ratings yet

- Proforma Inv 155678: MR Maric DamirDocument1 pageProforma Inv 155678: MR Maric DamirDamir MaricNo ratings yet

- Hampton Machine Tool CompanyDocument6 pagesHampton Machine Tool CompanyClaudia Torres50% (2)

- Home LoanDocument19 pagesHome LoanghanshyamNo ratings yet

- Recent Trends and Development of Banking System in IndiaDocument5 pagesRecent Trends and Development of Banking System in Indiavishnu priya v 149No ratings yet

- Csec Poa: Page 8 of 24Document1 pageCsec Poa: Page 8 of 24Tori GeeNo ratings yet

- Murabaha PDFDocument5 pagesMurabaha PDFWaqas Ahmad0% (1)

- Consolidated Bank & Trust Corporation vs. CA, GR No. 138569 PDFDocument2 pagesConsolidated Bank & Trust Corporation vs. CA, GR No. 138569 PDFxxxaaxxx100% (1)

- AAU On Tele BirrDocument72 pagesAAU On Tele BirrNatinael AbebeNo ratings yet

- Kotak Mahindra Bank Gets RBI Approval To Open Its First Overseas Branch in Dubai International Financial Centre (Company Update)Document3 pagesKotak Mahindra Bank Gets RBI Approval To Open Its First Overseas Branch in Dubai International Financial Centre (Company Update)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- HHDocument6 pagesHHJoyce BusaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Outreach in Microfinance Institutions:: Indicator of Success of MfisDocument6 pagesConcept of Outreach in Microfinance Institutions:: Indicator of Success of MfisRiyadNo ratings yet