Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review of Shereen Ratnagar's Book Titled 'Harappan Archaeology: Early State Perspectives' by Sudeshna Guha, Shiv Nadar University

Uploaded by

itharajuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review of Shereen Ratnagar's Book Titled 'Harappan Archaeology: Early State Perspectives' by Sudeshna Guha, Shiv Nadar University

Uploaded by

itharajuCopyright:

Available Formats

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

Chapter 9.indd 100 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

Perspectives from the

Indus: Contexts of

interaction in the Late

Harappan/Post-Urban

period

Rita P. Wright (New York University)

101

Chapter 9.indd 101 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

Introduction are providing new evidence with which to refine our

understanding of the latest phases of occupation in

The evidence for cultural interaction in the late third this region. Observable changes are based on artefact

and early second millennia BC between the Indus Valley inventories, architectural structures, archaeobotanical

and the Arabian Peninsula poses serious challenges to and zooarchaeological collections, regional surveys and

an understanding of trade relations during this period. palaeo-environmental data. Four of the mounds in the

Settlements on the alluvial plains of the Indus Valley, city remained occupied in the Late Harappan (Cemetery

which had been at the centre of the civilisation’s social, H, Mounds AB, E and F), although the site was reduced

political and economic activities, were either reduced in size to less than 30 hectares. In each area, there is both

in size or no longer occupied. As Indus cities fell into continuity and change. Studies of Cemetery H indicate

disrepair or were abandoned, settlements were founded that, in spite of some changes in burial practices, there

in other locations, populations shifted to previously more is continuity between the Urban and Late Harappan

marginal regions, and trade networks were reorganised. pottery styles. On Mound AB, the discovery of a hearth

The two regions most frequently cited as points of contact that is radiocarbon dated to ca. 1730 BC and a cache of

(Carter 2001; Potts 2005, 2009; Cleuziou and Tosi materials that included beads and other objects, some of

2007; Højlund and Andersen 1994; Laursen 2008) are which were produced using the same techniques applied

the Lower Indus and Gujarat, where the ceramic types in the Urban period, also show continuity.

Jhukar and Sorath Harappan have been discovered. One of the changes that did occur is modifications

Although these final stages of the Indus Valley in aspects of the economy. The agro-pastoral economy

civilisation are poorly understood, my purpose here is to at Harappa was based on a multi-cropping strategy in

briefly review what is known about the Late Harappan which cereal grasses were the staple food produced.

in order to move toward a better understanding of Indus Wheat and barley were grown in winter and millets

relations with the Arabian Gulf and its trading partners. and other drought-resistant crops during the summer

After a discussion of the Late Harappan, I focus on the monsoon season. In the Late Harappan, summer crops

Jhukar ceramics in the Lower Indus and the Sorath became more important and barley, a drought-resistant

Harappan and Late Harappan in Gujarat. crop, became the dominant cereal grain. There also

was an increase in crop diversity but, as new plants,

The Late Harappan/ such as rice were introduced, existing plants were not

abandoned (Weber 2003: 181–2). Finally, changes in

Post-urban – cropping patterns suggest a shift from the centralised

or communal processing practiced during the Urban

Regional Variability period to one that was smaller in scale in the Late

Harappan. This observation is based on the presence

It is important to stress that the evidence for the Late of residues of chaff among the seed remains, a possible

Harappan is uneven and many questions about these indication that processing was taking place in households

terminal phases remain unanswered. What we do know is (Weber 1999, 2003; Fuller and Madella 2000). Thus far,

that there were significant changes that began at around only a small sample of zooarchaeological evidence has

1900 BC in the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra alluvial plains been published for the Late Harappan, but those results

and in Kutch, where the major Harappan centers were show a shift in the dominance of cattle in the Urban

located. These changes included a reduction in the size period to sheep and possibly goat in the Late Harappan

of cities, the abandonment of some and more sustained (Miller 2004). This change may indicate a reduced need

occupation of others, the displacement of populations for traction animals used for transport and ploughing.

and the founding of new settlements. The changes Horses, donkeys, and camels were probably introduced

were gradual and not cataclysmic. They were the result into South Asia by the 2nd millennium BC (Meadow

of a complex of factors that included environmental, and Patel 2003: 83), but there is no evidence for their

economic, social, political and ideological changes presence at Harappa in the Late Harappan.

that differed regionally. Finally, as the interaction with Other economic changes and more broad-based

Arabia demonstrates, although the Indus civilisation was political and social differences also are evident. The black-

transformed, some institutions appear to have survived. slipped storage jars used in interregional and intercultural

I begin with a discussion of the Upper Indus, a transport systems are no longer produced. There is

region in which I have been engaged in field research a diminished presence of some craft technologies and

and where the results of recent research at Harappa the Harappan administrative system (writing, weights,

102

Chapter 9.indd 102 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

seals) all but disappears. Architecturally, new structures at Chanhu-daro but not an intrusion of a new cultural

were built that encroached on streets and public spaces, group (Possehl 1977: 244). Another study, by Rafique

and there was a general disorderliness although many Mughal (1990), compared the Jhukar pottery from

neighbourhoods continued to be populated (Meadow, Mohenjo-daro, Jhukar, Amri and Chanhu-daro to

Kenoyer and Wright 2001). ‘traditional’ urban types. In view of the overlap in styles

Finally, the results of palaeoclimate studies have and the mixed lots in which many were discovered, he

shown that there were frequent fluctuations in climate, concluded that the two types overlapped. Finally, based

precipitation levels and stream migrations throughout on a re-analysis of the site plan at Chanhu-daro, Heidi

the Urban and Late Harappan periods of occupation at Miller (2005) has argued against a break in the cultural

Harappa. These fluctuations were most dramatic in the sequence in spite of the disruptions in architecture. Later

Late Harappan. Results of survey data from the now dry in this chapter, I describe the Jhukar pottery in more

bed of the Beas River based on studies of soil sediments detail in view of its possible relevance to trade with the

and archaeoclimate modelling show a sharp decrease Gulf in the Late Harappan.

in rainfall patterns involving changes in precipitation While we can now assume that there was continuity

levels that are linked to variations in stream discharge between the Urban and Late Harappan periods in the

beginning at around 2000 BC (Wright, Byrson and Lower Indus in its terminal stages of occupation, there

Schuldenrein 2008). These results are complemented by were also significant changes in material culture that

soil studies at Harappa (Amundson and Pendall 1991, speak directly to the political economy in its final days.

Pendall and Amundson 1990). Additionally, the regional First, there is an absence of Jhukar pottery in any other

settlements on the Beas diminished in size and all but four region of the Indus, marking a break with the centres

were abandoned (Wright, Byrson and Schuldenrein 2008). in the Upper Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra plains, since,

Taken together, the evidence at Harappa and thus far, no Jhukar ceramics have been identified there.

its surrounding countryside documents a period of Second, terracotta figurines are absent from Lower

continuity and change. Harappa itself remained occupied Indus assemblages, a feature that represents a break with

for several hundred years after the Urban period until aspects of an Indus ideology. Third, cubical stone weights

at least 1700 BC (Kenoyer 1998) and possibly as long and square stamp seals disappear, signalling the end

as 1300 BC (Meadow, Kenoyer and Wright 2001). As of an administrative system that fostered interregional

I noted earlier, farmers appear to have been fine-tuned exchanges. Finally, the Jhukar phase is sparse, even when

to their environment, judging by the adjustments made viewed regionally. The sites listed earlier are among a very

to cultivation and cropping patterns throughout the few others aligned with this final era of urbanism in the

Urban and Late Harappan periods. Other evidence – Lower Indus. Recent surveys conducted by a team from

the disappearance of its administrative technology and the Shah Abdul Latif, Khairpur University, led by Nilofer

the absence of black-slipped transport jars – indicates Shaikh, did not yield any sites that could be assigned to

significant changes in the broader political economy. this period (pers. comm.; Wright 2009: Figs. 4.6 and 5.12

In the Lower Indus, Mohenjo-daro may have for Early and Urban Harappan distributions).

undergone a more rapid transformation than at Harappa. This limited amount of information suggests that

In any event, major buildings, such as the Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro continued to be occupied in the Late

were abandoned, and there was a general disorder Harappan, but that it did so with a population reducing

in its urban plan. At the nearby site of Chanhu-daro, at a faster rate than at Harappa. It is impossible to attach

that appears to have been a centre of craft production, an exact date to when settlements in the Lower Indus

Ernest Mackay (1943) found a similar disorder in which were abandoned but most, surely, around the beginning

buildings were less substantial than in the Urban period. of the 2nd millennium.

The discovery of a unique pottery style first identified The extensive research in the Lower Indus by Louis

at the site of Jhukar and found in the upper levels at Flam and his colleagues (Flam 1993, Shroder 1993,

Chanhu-daro suggested to him that there had been an Jorgensen et al. 1993) provides us with some of the

intrusion of a new culture into the Lower Indus in the environmental challenges that may have influenced the

Late Harappan. Subsequent studies of this evidence decline of populations in this region. The survey was

by a number of Indus scholars have cast serious doubt focused on changes in the Lower Indus river system

on Mackay’s interpretation. As Gregory Possehl noted and was based on field research, historical sources,

many years ago, the close similarities between the Urban geomorphic and landform reconstructions and aerial

Harappan wares and the Jhukar are a manifestation of photography. Interpretations of these data showed

a transitional phase that marked the end of occupation that over a period of several thousand years, there

103

Chapter 9.indd 103 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

were episodic and abrupt channel displacements in Issues like these cannot be resolved without additional

the Lower Indus, involving realignments in the river excavations, geoarchaeological research and the collection

system. Between 4000 and 2000 BC, Mohenjo-daro was of archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological evidence and

strategically located between two parallel river courses more details on other changes that would have affected

(Flam 1993, 1999), the Sindhu Nadi on the west and the the social, political and economic factors there.

Nara Nadi on the east. While these locations provided Two other regions of relevance are on the margins of

the city with extensive tracts for cultivation and animal the alluvial plain. To the west of the Indus in northern

husbandry, the shifting of the channels may have placed and southern Baluchistan, important settlement shifts

Mohenjo-daro in an imperilled position. and realignments of cultures were taking place. In

The shifts that occurred in the Lower Indus may have south-eastern Baluchistan, the Kulli complex that

been related to others that occurred upstream on the dominated the area in the Indus Urban period appears

Ghaggar-Hakra. Based on historical records, Wilhelmy to have ended by 1900 BC (Franke 2008: 669). In

(1969) proposed that flooding cycles documented during northern Baluchistan, however, while some settlements

several periods in the history of the Ghaggar-Hakra were abandoned coincident with the Late Harappan, the

had occurred in the Late Harappan, although there are excavations at Pirak, to the north-west of Jhukar, raise

no specific records dated to the Late Harappan. Other an interesting set of problems, since they may provide

evidence based on sediment samples from different stylistic links to the Jhukar phase (Kenoyer 1998: 177)

micro-environments on the Ghaggar plain by Marie- that would establish continuity of this tradition. Pirak

Agnès Courty documented drying conditions and was occupied between 1800 and 600 BC (Jarrige, Enault

disruptions of the predictable seasonal flooding cycle and Santoni 1979). Mackay had noted the similarities

(1995) of the Ghaggar in the Late Harappan, although of the Jhukar decoration with examples from northern

the precise timing of these events is uncertain. The Baluchistan but he discounted this possibility based on

drying of the Ghaggar-Hakra system affected major distance and difficulties of travel (Mackay 1943: 131). It

changes in the flow lines of the Nara Nadi, bringing is an interpretation that takes us beyond the limitations

about a ‘widespread abandonment of many sites and of this paper, but clearly is an issue worthy of some

a movement of population out of the Lower Indus additional investigation.

basin into adjacent and more “stable” areas’ (Flam To the south-east of the Indus plain in Kutch and

1999: 317). In Cholistan and settlements on the Hakra Gujarat, the trajectory of change varied within the

alluvial plain, Mughal set the end of the Late Harappan region. At Dholavira, the dramatic changes in its urban

in Cholistan between 1700 and 1500 BC. He based his layout are suggestive of a breakdown in civic authority.

dates on the results of excavations at settlements on the At Kuntasi, a major centre for the production of shell

Ghaggar plain, where there is stratigraphic continuity objects, industrial activities known from the Urban period

between Late Harappan and Painted Gray Ware (PGW) ceased, putting an end to the trade networks established

ceramic styles (Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1999). Reports between the site and the interior. These changes coincide

of terminal dates for the PGW vary from 1100–500 with the evidence from Harappa, where marine shell all

BC (Possehl 2003), 1200–800 BC (Kenoyer 1998), and but disappears (Kenoyer 1998: 175). Lothal continued

1700–1400 BC (Bisht 1982: 122), leaving doubts of the to be occupied until 1750 BC, though it was diminished

precise timing of these events. in size (from less than 4.2 ha). In addition, chert and

These environmental disruptions of annual flooding agate cubical stone weights at Lothal are replaced with

cycles made an impact on Mohenjo-daro’s agro- ‘truncated spheroid weights of schist and sandstone

pastoralist economy and its inter-regional networks in larger in size than the earlier ones’ and the type of seal

the Lower Indus and most likely on the Ghaggar-Hakra used differs from the more traditional square stamp seals

plains. In Cholistan and on the Ghaggar plain, there were (Rao 1985: 36), signalling the end of an administrative

settlement shifts to upstream locations, the movement system that fostered inter-regional exchanges.

of people and the founding of new settlements. Along with these changes, there is an increase in

Unfortunately, we do not have the kind of detailed data the number of settlements in Gujarat in the area of

available in other areas, to be discussed below in Gujarat Saurasthra. This was either the result of an influx of

and in my earlier discussion of the Upper Indus, with new groups or the settlement of hunter/gatherers. If the

which to determine whether people on the Ghaggar- former, these shifts parallel those that were taking place

Hakra plains and in the Lower Indus were making in north-west India, which are suggestive of a movement

adjustments to their agricultural and husbandry practices away from the alluvial plain and the principal centres

and the political consequences to the society as a whole. of the Indus. In any event, new aspects of material

104

Chapter 9.indd 104 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

culture and architectural building projects indicate a and Qala’at al-Bahrain, Dan Potts (2005) has pointed

revitalisation of the culture. At Rojdi, where there is a out parallels to recent finds in Rajasthan at Gilund in

good stratigraphic sequence, a new building project was the Ahar-Banas culture. As far as is known, there were

undertaken that included an outer gateway and has been no previous contacts between Rajasthan and the Gulf.

dated to 1750 BC (Possehl and Raval 1989). Other sites The round seals, sealings and tokens with geometric

in Saurasthra, such as Rangpur, may have survived to motifs have been discovered in a wide geographical

the end of the 2nd millennium BC (Rao 1963). sphere including at Chanhu-daro, Pirak, Nindowari

Rojdi is a small site (7.5 ha) – though larger than and the Bactrian Margiana Complex (BMAC). A study

Lothal – on the margins of the Indus, both physically conducted by Marta Ameri clarifies aspects of the

and culturally. The physical environment there is glyptic evidence (Ameri 2010). For now, we are left with

characterised by low levels of precipitation and sporadic an additional complication of an already complex issue

heavy rains during the monsoon. In the Urban period, regarding exchange relations in the Late Harappan and

its economy was based on an agricultural and pastoral the Gulf.

economy that included small-scale irrigation during

non-monsoon months and dry farming of millets during

summer monsoons. In Rojdi C, the Late Harappan, Understanding

plant-use involved the continuation of this pattern

but there also was ‘a broadening and intensification of ‘collapse’,

plant-use strategies’ (Weber 1991: 183). Interpreting

these patterns is complex, but Steven Weber, the transformations

archaeobotanist who analysed the plant remains at

Rojdi, suggests several possibilities that could account for

and trade networks

these changes. The abundance of some species that are

‘low-preference foods’ could be a response to food stress,

in the Late Harappan

while the intensification of cropping patterns might As I noted early in this paper, our evidence for the Late

suggest ‘changes in the ratio of population to resources’ Harappan is spotty and the chronology imprecise. There

(Weber 1991: 165) or a shift to household processing in are few absolute dates and a limited number of sites

which less preferred foods are present in seed residues, based on recent excavations involving multidisciplinary

as discussed at Harappa (S. Weber, pers. comm.). Still, teams with which to refine our understanding of the

the presence of non-indigenous plant species may Late Harappan. What can be said is that the changes

be related to the shifts occurring in other parts of the were variable regionally and there is no single cause.

Indus as described earlier. The increased density of At Mohenjo-daro and along the Ghaggar-Hakra, there

people brought about by immigration could also be a clearly were disruptions of the river systems, but we lack

contributing factor (Weber 1991: 166). precise data to determine whether they were coincident

In Gujarat, then, there were significant differences with similar changes elsewhere. On the other hand,

within the regional settlement pattern. At a time when at Harappa, where precipitation levels and changes

important settlements, such as at Kuntasi and Dholavira, in river systems are documented, the city appears to

were abandoned, new populations – possibly from the have continued to be populated – albeit by smaller

Lower Indus where there appears to have been a break numbers of people – for several hundred years after

down of the economic, social and political organisation these environmental changes occurred. In Gujarat, an

– moved into the region. At Rojdi, the multi-cropping influx of populations, possibly the result of migrations of

was a resilient strategy that sustained its agricultural people from the Lower Indus, also may have resulted in

economy during these changing times. More marginal changes in cropping patterns. In the latter two instances,

to the great centres of the Indus in the Urban period, the Harappans seem to have been fine-tuned to their

the Sorath Harappan sites may have remained ‘solidly environment and demonstrated resilience in the face of

buffered’ against the changes occurring on the alluvial changed circumstances.

plains (Meadow and Patel 2003: 86). What we can say with some certainty is that there

Finally, the recent evidence from the site of Gilund in was a breakdown in communication networks on the

Rajasthan presents new challenges that raise additional Indus alluvial plains. As I noted above, the absence

questions concerning the nature of contact and introduces of the weights, seals and script signalled a disruption

a new field of players. Based on comparisons of seals of trade patterns and some production systems in

and unfired clay tokens from Tell Abraq, Failaka, Saar general. More specifically, at Mohenjo-daro, it seems

105

Chapter 9.indd 105 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

unlikely that flows of resources to and from other Indus from Rojdi C (Possehl and Raval 1989: 96-99; Fig. 51.4,

settlements or resource zones continued. But questions 7–9); a looped design on a large jar (Cleuziou and Tosi

remain concerning the ceramics (Jhukar) from the Lower 2007: Fig. 292.4) to examples from Lothal (Rao 1985:

Indus, the Sorath Harappan and other Late Harappan Fig. 91), and the small jar (Cleuziou and Tosi 2007: Fig.

wares from Gujarat that may have made their way to 292.3) to the Fine Ware Jars at Rojdi (Possehl and Raval

the Arabian Peninsula. Following Possehl, the Sorath 1989: Fig. 52.4–5). This potential connection requires

Harappan refers to sites in Saurasthra, specifically here additional study.

Rojdi, while I use the more general term, Late Harappan, There do not appear to be significant changes in the

with reference to materials from Lothal (Possehl 1977: vessel forms and design from previous periods in the

248–253). Sorath Harappan (Possehl and Herman 1990: 300).

New forms evolved from older styles and include open

The Sorath

and closed-mouthed large storage jars, bowls that are

‘straight-sided and S-shaped … medium-sized pots

Harappan, Jhukar with long necks, jar stands and the Suarasthra lamp’.

Rims are beaded and everted downward; others are

and Late Harappan ‘outsplayed’ (Possehl and Herman 1990: 309). Almost all

of the Sorath Harappan are slipped, smoothed, painted,

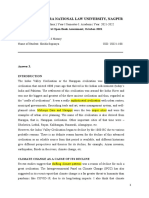

interaction polished and burnished. The vessel pictured in Fig. 1 is

a typical example of a Painted Fine Ware Storage jar

The population shifts and major changes at Harappan with a geometric design and graffito from Rojdi C. The

centres clearly altered Indus social and economic exterior of the vessel, which was colourised by Possehl

networks, but trade with cultural groups in the Gulf to conform to the original vessel, has colour effects in

continued in the Late Harappan. It has generally been which different parts of the body differ, a style that is

assumed that during the Indus Urban period trade characteristic of the Sorath Harappan pottery. On this

was carried out by merchants that either operated jar, the neck (reddish-brown slip), shoulder (light yellow-

autonomously or were very loosely controlled by urban

rulers. The continuation of trade with the Gulf raises

questions about its direction, its origins and social and

economic circumstances under which it took place in the

Late Harappan.

New ceramic forms, principally large storage jars,

originating in the Indus are found distributed at coastal

and interior sites on the Arabian Peninsula. This new

type of storage jar is present at Saar, Qala’at al-Bahrain,

Tell Abraq, and Shimal (Carter 2001). They appear in

stratigraphic levels that correspond approximately to the

early 2nd millennium BC. At Saar, intrusive ceramics

have been compared to the Sorath Harappan in Gujarat

at Rojdi and to Lothal B. Similarities have been noted

as well to the Jhukar at Mohenjo-daro and Chanhu-

daro (Carter 2001: 187, Table 1). At Qala’at al-Bahrain,

large jars assigned to an ‘eastern domain’ (Højlund and

Andersen 1994) have been identified as Sorath Harappan

(G. Possehl, pers. comm.). Storage jars from Shimal and

Tell Abraq also have close parallels to Late Harappan/

Sorath Harappan (Potts 1994, Carter 2001). At Ra’s al-

Jinz, fine red-ware bowls and a small jar with graffito

have been identified as ‘pottery of possible Indian origin’

(Cleuziou and Tosi 2007: 272) in the Wadi Suq period

(ca. 2000–1700 BC). Of the pottery illustrated, two

vessel forms (Cleuziou and Tosi 2007: Fig. 292.1–2) may Fig. 1. Large jar (colourised) from Rojdi C. (after Possehl

be comparable to Sorath Harappan Fine Ware Bowls and Raval 1989: Fig. 72). Courtesy: G.L. Possehl.

106

Chapter 9.indd 106 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

brown unslipped band), body (light-red slip) and base

(reddish-brown unslipped), and unslipped horizontal

band at the shoulder and base is described as a ‘“slipped-

cum-unslipped” surface treatment’ that ‘conveys a

“bichrome effect”’ (Possehl and Raval 1989: 131). This

bichrome effect and differences in colour shading appear

to be the result of variations in the mixing of pigments

and regulation of firing atmospheres. A difference

between the Sorath Harappan and the Late Harappan

Lothal wares is that a ‘small quantity’ of large jars at

Lothal were treated with a buff slip (Rao 1985: Fig. 85).

An analysis by B.B. Lal of the buff slip was described

as a ‘yellow ochreous calcareous clay … with some

white mica’ (Lal 1985: 472). The design elements on

the Rojdi jar are typical of the Sorath Harappan and

are described as ‘dots, crossing lines, net crossed and Fig. 3. Large jar (colourised) from Saar with ‘bichrome

wavy lines’ (Possehl and Raval 1989: 139). In addition effect’. Courtesy: R.A. Carter and R. Killick.

to the slips on this jar, others are described as reddish-

yellow and various hues of red. Paints are red, black,

brown, purple brown, grayish-brown and reddish-grey.

Fig. 4. Jar fragment from Saar with hatched rhombs

Courtesy: R.A. Carter and R. Killick.

Rojdi and examples from Lothal. In both instances, the

Fig. 2. Jar fragment from Rojdi C. Courtesy: G.L. Possehl. surface slip does not match the examples from Rojdi and

published descriptions. This same discrepancy in the use

The Sorath Harappan jar shown in Fig. 2 from Rojdi of exterior slips occurs with a jar fragment from Bahrain.

is a fragment with similar colour effects and a typical The motif on the jar (Fig. 5), from a burial mound in

hatched rhomb. In addition to the net or ‘crossing lines’ the Buri Cemetery at Hamad Town (S. T. Laursen, pers.

pattern in Fig. 2, the eight intersecting lines with balls comm. [Season 1982–83, BNN, Burial Mound 230])

at their tips is comparable to the Late Harappan jars at carries the ‘conventional flower’ design like the Rojdi

Lothal, where the motif is described as a ‘conventional example shown here and others at Lothal, but its exterior

flower’ (Rao 1985: Fig. 94.128–129; see also Nanavati, surface is black-on-orange. Although the vessel shapes

Mehta and Chowdhary 1971: Fig.18.IR 5). Leaves are and motifs on the examples from Saar (Figs. 3–4) and

the most common naturalistic motifs, but rarer forms the burial mounds at Hamad Town match the Sorath

are wheat chaff, peacock, bulls or fish. Other geometrics Harappan examples from Rojdi, the exterior slips on the

include: balls, squares or labyrinths, loops, intersecting examples from Saar (Figs. 3–4) and the burial mound in

loops, and straight and wavy, vertical or horizontal lines. Bahrain (Fig. 5) differ from those at Rojdi. On the other

Fillers include: hatches, dashes, chevrons, diagonal, hand, the large jar (Fig. 6) from Karzakhan Cemetery

horizontal or straight lines. The jar from Saar (Fig. 3) has at Hamad Town (S. T. Laursen, pers. comm. [Season

a ‘bichrome effect’ similar to the Rojdi C jar (Fig.1) and 1982-83, BNN, Burial Mound 1, Grave 20, Square

Fig. 4, a jar fragment from Saar, bears the hatched rhombs D5]) carries a peacock design that is represented at both

and wheat sprig typical of Sorath Harappan types from Rojdi and Lothal and the slip could match wares from

107

Chapter 9.indd 107 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

both Rojdi and Lothal. These various examples raise Many have voids from chaff that are clearly visible on

questions about the origins of the ceramics in Bahrain their surfaces, although others do not. Mica visible on

and elsewhere. Either of the above-illustrated jars might the surface is less dense than in Harappan ceramics. In

match the red slip on Late Harappan types from Lothal, addition to red-slipped wares with black paint, other

where they are described simply as ‘light to dull red’. designs are painted on a plain buff body (Fig. 8) or a

cream colored slip (Fig. 9). Paints are red, dark red and

blacks with brown and purple hues, the latter most likely

due to manganese oxide pigments. Technical features

such as trimming at the base and neck of the vessel are

consistent with the earlier Harappan pottery.

Fig. 6. Large jar with peacock motif (#A 19067: Karzakhan

Cemetery, Hamad Town, Season 1986–87, Excavation Area:

Fig. 5. Large jar with ‘conventional flower’ motif (#A 4780: BSW, Burial Mound: 1, Grave 20, Square D5).

Buri Cemetery, Hamad Town, Season 1982–83, Excavation Courtesy: S.T. Laursen.

Area: BNN, Burial Mound: 230). Courtesy: S.T. Laursen.

As I discussed in the above, the Jhukar pottery is found

in mixed lots at Chanhu-daro and re-analyses of the

this site plan, stratigraphy and comparisons with Harappan

Does pottery suggest that it was not intrusive. Many of the

mean Jhukar vessel forms are the same as the Harappan with

slight variations in base construction and motifs. Still,

of there are visible differences and it is reasonably easy to

tt’? differentiate them. The two sherds from Chanhu-daro Fig. 7. Jhukar and Harappan ceramics from Chanhu-daro

(Peabody Museum Collection, #40-30-60/6948). Copyright

(Fig. 7) illustrate some of these differences. The surface of 2009: President and Fellows of Harvard College.

the Jhukar ceramic on the left is matt and the red slip and

black paint have a slightly different red/orange hue from There are many different vessel shapes and design

the lustrous surface of the traditional Harappan wares motifs in the Jhukar corpus. The principal forms include

on the right. On closer inspection, the Jhukar fabrics are footed and pedestalled bases, spouted vessels, lamps

coarser and more porous than the Harappan ceramics. (these forms differ from the Sorath Harappan lamps),

108

Chapter 9.indd 108 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

and storage vessels. The latter differ from the black- black colours. The Jhukar potters produced bichrome

slipped storage jars from the preceding period. Many effects and true polychromes. For example, leaves may be

have narrow necks, while others have a slight ‘ribbing’ outlined in black and filled in with red paint and drawn

between the neck and shoulder as in (Fig. 8). Bases are on a field of cream-coloured slip. These eye-catching

flat or occasionally rounded. A major difference between designs show an innovative side to the potter’s craft and

the earlier Harappan pottery and the Jhukar are the a technical virtuosity in achieving the results.

design motifs. Although there is a resemblance between

the motifs employed in the previous period, Jhukar motifs

are principally geometric, in distinction to the Harappan

designs in which figurative motifs represent narrative

scenes of water plants and other natural phenomena.

Like the Sorath Harappan ceramics, bent and straight

leaves are common on Jhukar pottery and there also are

occasional peacocks and animals. Geometrics include:

balls with or without stems, rhombs, squares, loops,

straight, wavy and horizontal lines, but not intersecting

loops, labyrinths or the abstract conventional flower motif

common on the Sorath Harappan and Late Harappan

wares at Lothal. The same fillers employed on the Sorath

Harappan and the Lothal, Late Harappan wares are

all part of the Jhukar potter’s repertoire and motifs are

rarely left without some filler. Squares, for example, may

be completely filled with paint. Different from the Sorath

Harappan and Late Harappan at Lothal is a playful

aspect of surface treatments, in which fillers or dashed

and wavy lines are painted with alternating red and

Fig. 9. Jhukar ceramics with cream slip from Chanhu-daro

(Peabody Museum Collection, #40-30-60/6796). Copyright

2009: President and Fellows of Harvard College.

This very brief outline of the attributes of the Sorath

Harappan, Late Harappan at Lothal and Jhukar pottery

styles demonstrates that there are motifs, specificities of

form and technical elements that are common to both

while others set them apart from one another. The

Sorath Harappan and Late Harappan conventional

flower motif is not represented on the Jhukar; fillers are

common on both types but motifs that are totally filled

are only represented on the Jhukar. Cream-coloured

slips and true polychromes (the use of red, black and

cream slip on a single vessel) are only found on the

Jhukar with the exception of a few illustrated examples

from Lothal described earlier. The Jhukar polychrome

designs are rendered in primary colours (true reds and

blacks) often on cream slips. Their slipped exteriors are

red/orange and painted black. The style of decoration

involving unslipped panels at the shoulder found on

Sorath Harappan jars (Carter 2001: 185) appears

to be a unique feature that is not part of the Jhukar

Fig. 8. Jhukar, large jar fragment from Chanhu-daro ‘style’. Other design elements noted by Carter such as

(Peabody Museum Collection, #40-30-60/6851). Copyright the ‘enclosed net pattern’ (referred to here as squares,

2009: President and Fellows of Harvard College. triangles, rhombs, etc. with fillers of various types, i.e.

109

Chapter 9.indd 109 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Perspectives from the Indus: Contexts of interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban period

lines, dashes, etc.) and more ‘complex combination of or a continuation of those established in the preceding

motifs’ are, as he noted, decorations that are common to period. Based on comparisons of the mineralogy of a

Jhukar, Sorath Harappan and Late Harappan ceramics selection of pottery from Mature Harappan contexts

at Lothal (Carter 2001: 186). The design elements as from Ra’s al-Jinz and Lothal, V.D. Gogte (2000) have

‘dots, crossing lines, net crossed and wavy lines’ (Possehl documented close comparisons between the two. Is the

and Raval 1990: 139) are typical of the latter two and trade in the Late Harappan a continuation of earlier

rare on the Jhukar (Rao 1985: Figs. 88–89). contacts with Lothal or a reorganisation in which Rojdi,

Based on preliminary study of the Jhukar and the Lothal and possibly other settlements became trading

limited chemical analyses of the wares at Lothal, these partners with settlements in Arabia? The replacement

two types (possibly also the Sorath Harappan that have of the traditional Harappan weights with ‘truncated

not been analysed) appear to share a common technology spheroid weights of schist and sandstone’ that are larger

in which manganiferous pigments are manipulated for in size than the standard Harappan weights (Rao 1985:

different colour effects. Additionally, there are surface 36) and the careless rendering of script indicates some

features and technical elements, such as the occasional restructuring of trade networks may have taken place.

use of chaff, that suggest all three types are based on a Are the Sorath Harappan and Late Harappan (Lothal)

similar technology. There also are illustrated examples ceramic types in Gujarat from a single source or multiple

of sherds with similar designs, for example, occasional sources? Are the production technologies of the Sorath

chevron patterns common on Jhukar and isolated Harappan, Late Harappan and Jhukar ceramics a shared,

Late Harappan examples from Lothal (Rao 1985: Fig. independently invented style, or a product of emulation?

92.B90). Others include comparisons by Rao of types Did potters from the Lower Indus migrate to Gujarat or

at Lothal and Jhukar motifs (Rao 1985: Fig. 88 and exchange their wares, taking up routes travelled in earlier

Mackay 1943: Fig. 47). These comparisons among the Urban times? And finally, are these changes connected

Jhukar, Sorath Harappan and Late Harappan ceramics to the new finds at Gilund and possible restructured

need to be verified by a more thorough study based on relations within neighbouring regions of Rajasthan

macro- and microscopic analyses of their stylistic and and the Ahar-Banas culture (Potts 2005)? There clearly

technological attributes. are more avenues of research needed in order to fill

in important gaps in our understanding of this critical

Conclusions and period and its relations with cultures in Arabia.

further questions Robert Carter, Robert Killick, Steffen Terp Laursen and Gregory Possehl were most

generous in providing me with the colour illustrations. Steve Weber, Laursen, and Possehl

Returning to parallels with the design and form discussed various aspects of the paper with me. Any errors are mine alone.

of ceramics present on the Arabian Peninsula, this

comparison suggests that the closest parallels are to the

Sorath Harappan with some caveats. There are many

similarities in vessel form and design motifs, but the

surface characteristics, their colour and lustre, of the

Sorath Harappan from Rojdi, though possibly not

from Lothal, differ from the examples from Bahrain.

Hand examination of Sorath Harappan from Rojdi

and at other sites, especially Lothal, may clarify

these differences. Still, the presence of the signature

‘conventional flower’ motif, the use of rhombs and fillers

demonstrate contact between Arabia and the region of

Gujarat during this period and requires more intensive

study. Finally, Cleuziou and Tosi (2008) have suggested

that the bowls discovered in Oman are imports. Their

closest parallels are also to the Sorath Harappan. There

are no comparable forms among the Jhukar types.

What also remains unclear and could be resolved by

sourcing and technical analyses is whether the Sorath

Harappan ceramics represent new exchange relations

110

Chapter 9.indd 110 5/3/12 1:49 PM

Fifty Years of Emirates Archaeology

Bibliography

Ameri, M. 2010 ‘Sealing at the Edge of the Middle Asian Interaction Sphere: The Méry, S. 2000. Les céramiques d’Oman e l’Asie moyenne: Une archéologie des échanges à l’Âge du

View from Gilund, Rajasthan, India, Sept. 2010’. Ph.D. thesis, Institure of Fine Arts, Bronze. Paris: Éditions du CNRS.

New York University. Miller, H. 2005. ‘A new interpetation of the stratigraphy at Chahnu-daro’. In: Jarrige,

Amundson, R. and Pendall, E. 1991. ‘Pedology and Late Quaternary environments C. and Lefèvre, V., eds. South Asian Archaeology 2001. Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les

surrounding Harappa: A review and synthesis’. In: Meadow, R., ed. Harappa Civilisations, pp. 253–256.

Excavations 1986–1990. Madison: Prehistory Press, pp. 13–27. Miller, L.J. 2004. ‘Urban economies in early states: The secondary products

Bisht, R.S. 1982. ‘Excavations at Banawali: 1974–77’. In: Possehl, G.L., ed. Harappan revolution in the Indus civilization’. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University.

Civilization: A contemporary perspective. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH, pp.113–124. Mughal, M.R. 1990. ‘The decline of the Indus Civilization and the Late Harappan

Carter, R.A. 2001. ‘Saar and its external relations: New evidence for interaction between period in the Indus Valley’. Lahore Museum Bulletin 3/2: 1–17.

Bahrain and Gujarat during the early second millennium BC’. AAE 12:183–201. Nanavati, S.J.M., Mehta, R.N. and Chowdhary, S.N. 1971. Somnath, 1956, being a

Clark, S.R. 2007. ‘The social lives of figurines: Reconstructing third millennium B.C. report of excavations. Ahmedabad: Gujarat Dept. of Archaeology.

terracotta figurines at Harappa (Pakistan)’. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University. Pendall, E. and Amundson, R. 1990. ‘The stable isotope chemistry of pedogenic

Cleuziou, S. 2000. ‘Ra’s al-Jinz and the prehistoric coastal cultures of the Ja’alan’. carbonate in an alluvial soil from the Punjab, Pakistan’. Soil Science 149/4:

JOS 11:19–73. 199–211.

Cleuziou, S and Tosi, M. 2007. In the shadow of the ancestors: The prehisotric foundations of Possehl, G.L. 1977. ‘The end of a state and the continuity of a tradition: A discussion

the early Arabian civilization in Oman. Muscat: Ministry of Heritage and Culture. of the Late Harappan’. In: Fox, R.G., ed. Realm and region in traditional India. Durham:

Courty, M.-A. 1995. ‘Late quaternary environmental changes and natural constraints Carolina Academic Press, pp. 234–254.

to ancient land use (North-west India)’. In: Johnson, E., ed. Ancient Peoples and Possehl, G.L. 1980. Indus Civilization in Saurashtra. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation.

Landscapes. Lubbock: Museum of Texas Tech University, pp.105–26. Possehl, G.L. 2003. The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective. New York: Alta

Crawford, H. 2001. ‘Early Dilmun seals from Saar. Ludlow’: Archaeology International. Mira Press.

Flam, L. 1993. ‘Fluvial geomorphology of the Lower Indus basin (Sindh, Pakistan) Possehl, G.L. and Raval, M.H. 1989. Harappan Civilization and Rojdi. Oxford: Oxford

and the Indus Civilization’. In: Shroder, J.F., ed. Himalayas to the sea: Geology, and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Geomorphology and the Quaternary. New York: Routledge, pp. 265–87. Possehl, G.L. and Herman, C.F. 1990. ‘The Sorath Harappan: A new regional

Flam, L. 1999. ‘Ecology and population mobility in the prehistoric settlement of the manifestation of the Indus Urban Phase’. In: Taddei, M., ed. South Asian Archaeology

Lower Indus Valley, Sindh, Pakistan’. In: Meadows, A. and P. S., eds. The Indus River: 1987. Rome: IsMEO, pp. 295–319.

Biodiversity, Resources, Humankind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 313–23. Potts, D.T. 1990. The Arabian Gulf in Antiquity, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Franke, U. 2008. ‘Baluchistan and the Borderlands’. In: Pearsall, D.M., ed. Encyclopedia Potts, D.T. 1994. ‘South and Central Asian elements at Tell Abraq (Emirate of Umm

of Archaeology. New York: Academic Press, pp. 651–670. al-Qaiwain, United Arab Emirates), c. 2200 BC–AD 400’. In: Parpola, A. and

Frenez, D. and Tosi, M. 2005. ‘The Lothal sealings: Records from an Indus Koskikallio, P., eds. South Asian Archaeology 1993, vol. 2. Helsinski: Annales Academiae

Civilization port town at the eastern end of the maritime trade network across the Scientiarum Fennicae, B 271, pp. 615–628.

Arabian Sea’. In: Perna, M. ed. Studi in Onore di Enrica Fiandra. Contributi di Archaeologia Potts, D.T. 2005. ‘A note on Post-Harappan seals and sealings from the Persian Gulf ’.

Egea e Vicinorientale. Paris: De Boccard, pp. 65–103. Man and Environment 30/2:108–111.

Fuller, D.Q. and Madella M. 2000. ‘Issues in Harappan archaeobotany: Retrospect Potts, D.T. 2009. ‘The archaeology and early history of the Persian Gulf ’. In: Potter,

and prospect’. In: Settar, S. and Korisetter, R. eds. Indian archaeology in retrospect, Vol. L.G., ed. The Persian Gulf in history. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.27–55.

II. Protohistory. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 371–408. Rao, S.R. 1963. Excavations at Rangpur and other explorations in Gujarat. Ancient India

Gogte, V.D. 2000. ‘Indo-Arabian maritime contacts during the Bronze Age: Scientific 18–19: 5–207.

study of pottery from Ras al-Junayz Oman’. ADUMATU 2: 7–14. Rao, S.R. 1979. Lothal: A Harappan Port Town, 1955–62, vol. 1. New Delhi: Memoirs

Højlund, F. and Andersen, H.H. 1994. ‘Qala’at al-Bahrain, Vol. 1: The Northern of the Archaeological Survey of India.

City Wall and the Islamic Fortress’. Aarhus: JASP, 30/1. Rao, S.R. 1985. Lothal: A Harappan Port Town, 1955–62, vol. 2. New Delhi: Memoirs

Jarrige, J.- F. 2008. ‘The Treasure of Tepe Fullol’. In: Hiebert, F. and Cambon, P., of the Archaeological Survey of India.

eds. Afghanistan: Hidden treasures from the National Museum, Kabul. Washington, D.C.: Shaffer, J.G. and Lichtenstein, D. 1999. ‘Migration, philology and South Asian

National Geographic, pp. 67–79. Archaeology’. In: Bronkhorst, J. and Deshpande, M., ed. Aryan and non-Aryan in South

Jarrige, J.-F., Enault, J-F. and Santoni, M. 1979. Fouilles de Pirak. Paris: De Boccard. Asia. Cambridge: Harvard Oriental Series, pp. 239–260.

Jorgenson, D.W., Harvey, M.D., Schumm, S.A. and Flam, L. 1993. ‘Morphology and Shroder, J.F. 1993. Himalayas to the sea: Geology, geomorphology and the Quaternary. New

dynamics of the Indus River: Implications for the Mohenbjo-Daro site’. In: Shroder, York: Routledge.

J.R., ed. Himalayas to the sea: Geology, geomorphology and the Quarternary. New York: Weber, S.A. 1991. Plants and Harappan Subsistence: An Example of Stability and Change from

Routledge, pp. 288–326. Rojdi. Delhi: Oxford and IBH and American Institute of Indian studies.

Kenoyer, J.M. 1998. Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Karachi: Oxford Weber, S.A. 1999. ‘Seeds of urbanism: Paleoethnobotany and the Indus Civilization’.

University Press. Antiquity 73: 813–26.

Lal, B.B.1985. ‘Report on pottery from Lothal’. In: Rao, S.R. Lothal: A Harappan Port Town, Weber, S.A. 2003. ‘Archaeobotany at Harappa: Indications for change’. In: Weber,

1955–62, vol. 2. New Delhi: Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 461–474. S. and Belcher, W.R., eds. Indus Ethnobiology: New perspectives from the field. Lanham:

Laursen, S.J. 2008 ‘Early Dilmun and its rulers: New evidence of the burial mounds of Lexington Books, pp. 175–198.

the elite and the development of social complexity, 2200–1750 B.C.’ AAE 19:155–166. Wilhelmy, H. 1969. ‘Das Urstromtal am Ostrand der Indusebene und das Saraswati

Laursen, S.J. n.d. ‘The emergence of mound cemeteries in Early Dilmun: New Problem’. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie 8: 76–83.

evidence of a proto-cemetery and its genesis, c. 2050–2000 BC.’ In: Weeks, L.R. and Wright, R.P. 1991. ‘Patterns of technology and the organization of production at

Porter, A., eds. Death, burial and the transition to the afterlife in Arabia and adjacent regions. Harappa’. In: Meadow, R.H., ed. Harappa excavations 1986–1990: A multidisciplinary

Mackay, E.J.H. 1943. ‘Chanhu-daro Excavations 1935–36’. New Haven: AOS 20. approach to third millennium urbanism. Madison: Prehistory Press, pp. 71–88.

Meadow, R.H. and Patel, A. K. 2003. ‘Prehistoric pastoralism in North-western Wright, R.P. 2002. ‘Revisiting interaction spheres – Social boundaries and

South Asia from the Neolithic through the Harappan period’. In: Weber, S.A. and technologies on inner and outermost Frontiers’. Iranica Antiqua 37: 403–417.

Belcher, W.R., eds. Indus Ethnobiology. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 65–93. Wright, R.P. 2010. The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, economy and society. Cambridge:

Meadow, R.H., Kenoyer, J.M. and Wright, R.P. 2001. ‘Harappa Archaeological Cambridge Unversity Press.

Research Project: Harappa Excavations 2000 and 2001’. Unpubl. report submitted Wright, R.P., Byrson, R. and Schuldenrein, M.A. 2008. ‘Water supply and history:

to the Dept. of Archaeology, Government of Pakistan. Harappa and the Beas Regional Survey’. Antiquity 82: 37–48.

111

Chapter 9.indd 111 5/3/12 1:49 PM

You might also like

- Lands and Peoples in Roman Poetry: The Ethnographical TraditionFrom EverandLands and Peoples in Roman Poetry: The Ethnographical TraditionNo ratings yet

- Late Harappan Culture Marked Transition from Mature Harappan PhaseDocument36 pagesLate Harappan Culture Marked Transition from Mature Harappan PhasejahangirNo ratings yet

- q2n39 PDFDocument8 pagesq2n39 PDFitharajuNo ratings yet

- 61f36aa2be60120220128040138UG HISTORY - HONS - PART-1 - PAPER-1 - INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION - PART-4Document24 pages61f36aa2be60120220128040138UG HISTORY - HONS - PART-1 - PAPER-1 - INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION - PART-4jasminebrar302No ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocument31 pagesIndus Valley CivilizationMitchell JohnsNo ratings yet

- The Decline of the Indus Civilization and Emergence of the Late Harappan PeriodDocument26 pagesThe Decline of the Indus Civilization and Emergence of the Late Harappan PeriodSila MalikNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Harappan Civilization () (1)Document24 pagesChapter 2 Harappan Civilization () (1)lalitNo ratings yet

- Harappa 3Document13 pagesHarappa 3Swarlatha PandeyNo ratings yet

- Mohenjo Daro City of The Indus ValleyDocument9 pagesMohenjo Daro City of The Indus ValleykitabighunNo ratings yet

- Mohenjo - Daro Floods:: A Reply'Document9 pagesMohenjo - Daro Floods:: A Reply'lou CypherNo ratings yet

- Unit Diffusion and Decline: 9.0 ObjectivesDocument12 pagesUnit Diffusion and Decline: 9.0 ObjectivesamanNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley Civilization's Enigmatic Cities RevealedDocument10 pagesIndus Valley Civilization's Enigmatic Cities RevealedSurendra AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Indus Urbanism - New Perspectives On Its Origin & CharacterDocument40 pagesIndus Urbanism - New Perspectives On Its Origin & CharacterimmchrNo ratings yet

- Study of The Indus Script - Special Lecture-Asko ParpolaDocument62 pagesStudy of The Indus Script - Special Lecture-Asko ParpolaVeeramani ManiNo ratings yet

- Study of The Indus Script PDFDocument39 pagesStudy of The Indus Script PDFparthibanmaniNo ratings yet

- Beginning of the Indus CivilisationDocument62 pagesBeginning of the Indus CivilisationMahak JainNo ratings yet

- Notes and Assignment For History IX, XI and XII - Chapter-1 Indus Valley CivilizationDocument10 pagesNotes and Assignment For History IX, XI and XII - Chapter-1 Indus Valley CivilizationleenaapNo ratings yet

- Conningham and Manuel 2009Document14 pagesConningham and Manuel 2009shivatvaNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocument47 pagesIndus Valley Civilisationdebaship6529No ratings yet

- Harappan Civilization 1Document15 pagesHarappan Civilization 1Anshu GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Harappan Civilization-I : 5.0 ObjectivesDocument15 pagesUnit 5 Harappan Civilization-I : 5.0 ObjectivesJyoti SinghNo ratings yet

- Harappan Civilization - Markings-2023-24Document11 pagesHarappan Civilization - Markings-2023-24Sarah BNo ratings yet

- HarappaDocument5 pagesHarappaayandasmtsNo ratings yet

- LANE, P. Use EtnografyDocument8 pagesLANE, P. Use EtnografyDavid LugliNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley Civilisation - WikipediaDocument41 pagesIndus Valley Civilisation - WikipediaAli AhamadNo ratings yet

- Harappan Civilisation: Name, Origin and ChronologyDocument10 pagesHarappan Civilisation: Name, Origin and ChronologyYaar Jigree Season 3No ratings yet

- Module 3Document13 pagesModule 3marvsNo ratings yet

- Cultural Convergence in The NeolithicDocument17 pagesCultural Convergence in The Neolithictoto grossoNo ratings yet

- Early Farming and Iron Age Cultures of South IndiaDocument12 pagesEarly Farming and Iron Age Cultures of South IndiaNeha NehaNo ratings yet

- History Topic-Wise NotesDocument21 pagesHistory Topic-Wise NotesrockerNo ratings yet

- History Book L03Document18 pagesHistory Book L03ajawaniNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of the Indus Valley CivilizationDocument11 pagesThe Rise and Fall of the Indus Valley CivilizationSamrat ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- America's First City The Case of Late Archaic Caral Ruth Shady SolisDocument40 pagesAmerica's First City The Case of Late Archaic Caral Ruth Shady SolisAlvaro Collao TamayoNo ratings yet

- HISTORY Answer SheetDocument13 pagesHISTORY Answer SheetShrida SupunyaNo ratings yet

- Lec 1.2 (Ivc)Document45 pagesLec 1.2 (Ivc)Aman SinghNo ratings yet

- Kenoyer2008 Indus Valley ArticleDocument20 pagesKenoyer2008 Indus Valley ArticleSynchan ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocument45 pagesIndus Valley CivilisationRajesh Reghu Nadh NadhNo ratings yet

- Bio-Archaeological Studies at Konar Sandal, Halil Rud Basin, Southeastern IranDocument26 pagesBio-Archaeological Studies at Konar Sandal, Halil Rud Basin, Southeastern IranIdea HistNo ratings yet

- Decline of HarapansDocument11 pagesDecline of HarapansLeah EapenNo ratings yet

- BR Mani Kunal BhirranaDocument19 pagesBR Mani Kunal BhirranaLalit MishraNo ratings yet

- INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION: ANCIENT SOCIETY ALONG INDUS RIVERDocument29 pagesINDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION: ANCIENT SOCIETY ALONG INDUS RIVERjahangirNo ratings yet

- Origin of Harappan CivilisationDocument7 pagesOrigin of Harappan CivilisationAaquib yonusNo ratings yet

- دوموز 2Document25 pagesدوموز 2mehdaiNo ratings yet

- Islam Architecture (Reviewer)Document10 pagesIslam Architecture (Reviewer)Ryn LahoylahoyNo ratings yet

- Indus Civilization History NotesDocument9 pagesIndus Civilization History Notesmohammad azimNo ratings yet

- Sacred Landscapes of Siberia Symbolic Uses of SpacDocument5 pagesSacred Landscapes of Siberia Symbolic Uses of SpacDanaGrujićNo ratings yet

- Andean Ecology and Civilization An InterDocument2 pagesAndean Ecology and Civilization An Interf.pastoreNo ratings yet

- Ancient History 05 - Daily Notes - (Sankalp (UPSC 2024) )Document12 pagesAncient History 05 - Daily Notes - (Sankalp (UPSC 2024) )nigamkumar2tbNo ratings yet

- Newly Discovered Protohistoric Sites in West Bengal PDFDocument4 pagesNewly Discovered Protohistoric Sites in West Bengal PDFBidhan HalderNo ratings yet

- Ancient-Medieval History and Indian Culture Lecture-2: Harappan CivilisationDocument2 pagesAncient-Medieval History and Indian Culture Lecture-2: Harappan CivilisationshagunNo ratings yet

- Intersocietal Transfer of Hydraulic Technology in Precolonial South Asia: Some Reflections Based On A Preliminary InvestigationDocument28 pagesIntersocietal Transfer of Hydraulic Technology in Precolonial South Asia: Some Reflections Based On A Preliminary InvestigationGirawa KandaNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument4 pagesBrochuresarennibaran365No ratings yet

- Archaeological Sites of Early Harappan and Harappan CivilizationsDocument31 pagesArchaeological Sites of Early Harappan and Harappan Civilizationsmadhu anvekarNo ratings yet

- Unit Test 2 IgnouDocument26 pagesUnit Test 2 IgnouSudarshan CNo ratings yet

- Pathways To Asian Civilizations: Tracing The Origins and Spread of Rice and Rice CulturesDocument16 pagesPathways To Asian Civilizations: Tracing The Origins and Spread of Rice and Rice CulturesMarlhen Euge SanicoNo ratings yet

- Nila 97Document8 pagesNila 97reevzNo ratings yet

- 3d2 Stress Props of NickelDocument4 pages3d2 Stress Props of NickelitharajuNo ratings yet

- Fish Symbolism and Fish Remains in Ancient South Asia by William R. BelcherDocument20 pagesFish Symbolism and Fish Remains in Ancient South Asia by William R. BelcheritharajuNo ratings yet

- A Young Couple's Grave Found in The Rakhigarhi Cemetery of The Harappan CivilizationDocument5 pagesA Young Couple's Grave Found in The Rakhigarhi Cemetery of The Harappan CivilizationitharajuNo ratings yet

- Wa 77 ZDocument22 pagesWa 77 ZitharajuNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Practices As Gleaned From The Tamil Literature of The Sangam AgeDocument23 pagesAgricultural Practices As Gleaned From The Tamil Literature of The Sangam AgegaurnityanandaNo ratings yet

- Incas - Lords of Gold and Glory (History Arts Ebook)Document176 pagesIncas - Lords of Gold and Glory (History Arts Ebook)lancelim100% (3)

- Excavaciones en BabiloniaSin Título 02Document76 pagesExcavaciones en BabiloniaSin Título 02romario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Demography and ArchaeologyDocument5 pagesDemography and ArchaeologyConstantin PreoteasaNo ratings yet

- Ancient West & East 4,2 (2005, 291pp) - LZDocument291 pagesAncient West & East 4,2 (2005, 291pp) - LZMarko MilosevicNo ratings yet

- Piramida TiraneDocument4 pagesPiramida TiraneAuiola NeziriNo ratings yet

- Oxford Big Ideas Geography History 7 Historians Toolkit PDFDocument22 pagesOxford Big Ideas Geography History 7 Historians Toolkit PDFLi CamarãoNo ratings yet

- PrehistoryDocument73 pagesPrehistoryTristan TaksonNo ratings yet

- Mesopotamia WebquestDocument2 pagesMesopotamia Webquestapi-236682830No ratings yet

- How Were The Pyramids Built Final EssayDocument5 pagesHow Were The Pyramids Built Final Essayapi-254288485No ratings yet

- Why Israel Should Own The Land?Document2 pagesWhy Israel Should Own The Land?api-214728543No ratings yet

- Altamira AdorantenDocument14 pagesAltamira AdorantentatjaNo ratings yet

- UCSP 11 12 Q1 0504 Importance of Artifacts in Interpreting Social Cultural Political and Economic Processes PSDocument15 pagesUCSP 11 12 Q1 0504 Importance of Artifacts in Interpreting Social Cultural Political and Economic Processes PSumalijustinerainNo ratings yet

- The Legend of King ArthurDocument14 pagesThe Legend of King ArthurdbrevolutionNo ratings yet

- World Heritages - EthiopiaDocument36 pagesWorld Heritages - EthiopiaFriti FritiNo ratings yet

- Langford 1983 - Our Heritage - Your Playground PDFDocument7 pagesLangford 1983 - Our Heritage - Your Playground PDFHéctor Cardona MachadoNo ratings yet

- 6 SSCDocument2 pages6 SSCsamina shaikhNo ratings yet

- Project MGTDocument36 pagesProject MGTMd Tarek RahmanNo ratings yet

- Project Safety, Health and Environment PlanDocument54 pagesProject Safety, Health and Environment PlanKhaty Jah100% (2)

- Journal of Thee Pig 014357 MBPDocument178 pagesJournal of Thee Pig 014357 MBPghostesNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Module Final Version-1Document163 pagesAnthropology Module Final Version-1muse tamiru100% (2)

- Magathane CavesDocument31 pagesMagathane Cavesrkaran22No ratings yet

- Temple Church CMPDocument45 pagesTemple Church CMPWin ScuttNo ratings yet

- Ancient Neolithic Architecture GuideDocument1 pageAncient Neolithic Architecture GuidedecayNo ratings yet

- Runic 1Document22 pagesRunic 1Anna WangNo ratings yet

- Formal Synthesis Essay 1Document3 pagesFormal Synthesis Essay 1api-382291430No ratings yet

- Rehabilitating Beira LakeDocument68 pagesRehabilitating Beira Lakedjgiumix100% (1)

- Ancient Egypt Course Covers Pharaohs, Pyramids and HistoryDocument6 pagesAncient Egypt Course Covers Pharaohs, Pyramids and HistoryAda LovelaceNo ratings yet

- Catherine Sease-The Conservation of Archeological MaterialsDocument15 pagesCatherine Sease-The Conservation of Archeological MaterialsDaniel DoowyNo ratings yet

- Dominus Et Domna From CristestiDocument13 pagesDominus Et Domna From CristestiLóránt VassNo ratings yet