Professional Documents

Culture Documents

072415-499 1 PDF

Uploaded by

druzair007Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

072415-499 1 PDF

Uploaded by

druzair007Copyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Diagnostic reliability of the cervical vertebral maturation method and

standing height in the identification of the mandibular growth spurt

Giuseppe Perinettia; Luca Contardob; Attilio Castaldoc; James A. McNamara, Jr.d;

Lorenzo Franchie

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the capability of both cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) stages 3 and 4

(CS3-4 interval) and the peak in standing height to identify the mandibular growth spurt throughout

diagnostic reliability analysis.

Materials and Methods: A previous longitudinal data set derived from 24 untreated growing

subjects (15 females and nine males,) detailed elsewhere were reanalyzed. Mandibular growth

was defined as annual increments in Condylion (Co)–Gnathion (Gn) (total mandibular length) and

Co–Gonion Intersection (Goi) (ramus height) and their arithmetic mean (mean mandibular growth

[mMG]). Subsequently, individual annual increments in standing height, Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG

were arranged according to annual age intervals, with the first and last intervals defined as 7–8

years and 15–16 years, respectively. An analysis was performed to establish the diagnostic

reliability of the CS3-4 interval or the peak in standing height in the identification of the maximum

individual increments of each Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG measurement at each annual age interval.

Results: CS3-4 and standing height peak show similar but variable accuracy across annual age

intervals, registering values between 0.61 (standing height peak, Co-Gn) and 0.95 (standing height

peak and CS3-4, mMG). Generally, satisfactory diagnostic reliability was seen when the

mandibular growth spurt was identified on the basis of the Co-Goi and mMG increments.

Conclusions: Both CVM interval CS3-4 and peak in standing height may be used in routine

clinical practice to enhance efficiency of treatments requiring identification of the mandibular

growth spurt. (Angle Orthod. 2016;86:599–609.)

KEY WORDS: Orthodontics; Cervical vertebrae; Standing height; Mandibular growth; Diagnosis;

Accuracy

INTRODUCTION

a

Research Fellow, Department of Medical, Surgical and

Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Trieste, Several dentofacial orthopedic treatments on grow-

Trieste, Italy. ing patients have been shown to have their maximal

b

Assistant Professor, Department of Medical, Surgical and

Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Trieste, effect if performed during specific skeletal maturational

Trieste, Italy. phases, such as the circumpubertal growth spurt.1,2

c

Professor, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health This is particularly true for skeletal Class II malocclu-

Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Trieste, Trieste, sion patients, in whom functional appliances may have

Italy.

d

Thomas M. and Doris Graber Endowed Professor of

Dentistry Emeritus, Department of Orthodontics and Pediatric

Corresponding author: Dr Giuseppe Perinetti, Piazza Ospitale

Dentistry, School of Dentistry; Professor Emeritus of Cell and

1, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences,

Developmental Biology, School of Medicine; Research Pro-

University of Trieste, Trieste, Friuli Venezia Giulia 34129, Italy

fessor Emeritus, Center for Human Growth and Development,

(e-mail: G.Perinetti@fmc.units.it)

The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich; and Private

Practice , Ann Arbor, Mich.

e

Assistant Professor, Department of Orthodontics, School of Accepted: October 2015. Submitted: July 2015.

Dentistry, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, Department of Published Online: November 24, 2015

Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, The G 2016 by The EH Angle Education and Research Foundation,

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. Inc.

DOI: 10.2319/072415-499.1 599 Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

600 PERINETTI, CONTARDO, CASTALDO, McNAMARA, FRANCHI

increased skeletal effects if treatment is performed identification of the mandibular growth spurt initially

during peak mandibular growth.2,3 In this regard, was considered.

chronological age has been shown not to be a valid

predictor of skeletal maturation phases.4,5 Indeed, MATERIALS AND METHODS

the clinical applicability of chronological age as an

The original data set used herein is from the files of

indicator of the onset of the pubertal growth spurt

the University of Michigan Elementary and Secondary

in the individual patient is limited, as the growth spurt

School Growth Study (UMGS), as detailed in a pre-

is influenced by several other factors, including vious article.9

genetics, ethnicity, nutrition, and socioeconomic

status.6 Subjects

Previous studies have focused on the correlations

between clinical indicators of growth phase, including Briefly, the sample used in the original study9 and

cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) and standing reanalyzed herein included 24 growing subjects

height, and mandibular growth spurt. These studies (15 females and 9 males; age range 7–17 years) from

were either cross sectional7 or longitudinal8–15 (for the UMGS archives who provided longitudinal data for

review, see Flores-Mir et al.5). standing height corresponding to the consecutive

In spite of these studies, the diagnostic reliability of cephalograms for all the examined subjects. Such

the interval between CVM stages 3 and 4 (CS3-4)1 and subjects were included because they had six consec-

the peak in standing height in the identification of the utive annual recordings that encompassed all CVM

mandibular growth spurt on an individual basis is yet stages from 1 to 6, regardless of chronological age.

undetermined. Indeed, correlations between parame-

ters do not necessarily imply diagnostic accuracy.16,17 Data Collection

From a clinical standpoint, diagnostic accuracy on A modified version of the original method for

individual patients, rather than correlation on a group assessment of CVM developed by Lamparski18 was

of subjects, has major implications. adopted, with adjustments allowing for the appraisal of

Only one study7 has reported on the diagnostic skeletal age, as previously reported by Franchi et al.9

capability of the CVM method in the identification of the Further details of the data recording and cephalometric

mandibular growth spurt by using receiver operating tracing method are reported in the original article.9 For

characteristics (ROC) curves. ROC curve analysis can the present study, data on mandibular size, defined as

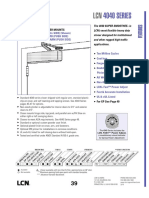

be used to evaluate the capability of a test to Condylion (Co)–Gnathion (Gn) (total mandibular

discriminate “diseased cases” from “normal cases.” length) and Co–Gonion Intersection (Goi) (ramus

However, this study7 was based on a cross-sectional height), were used. In addition, a mean mandibular

sample and was limited to the analysis of the area growth (mMG) parameter defined as the arithmetic

under the curve. mean of Co-Gn and Co-Goi (Figure 1) also was

One of the reasons underlying this noteworthy lack considered.

of data may be the difficulty associated with obtaining The method error for the cephalometric tracing

diagnostic parameters, such as sensitivity, specificity, ranged from 0.15 to 0.81 mm, and inter-/intraoperator

and accuracy, from longitudinal data in a subset of agreement levels in the assessment of the CVM

selected subjects all with a predetermined condition stages were above 98%.9 Descriptive statistics of the

(mandibular growth spurt) or a diagnostic outcome examined parameters according to each CVM stage

(a given CVM stage). Yet the identification of a man- have been reported elsewhere.9

dibular growth spurt requires longitudinal data, and it is

defined according to time intervals rather than being Definition of Standing Height Peak and Mandibular

a cross-sectional recording. Growth Spurt

To overcome such limitations in the present Annual or annualized increments of standing height,

study, individual CVM stages and increments in Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG, were calculated for each

standing height and mandibular growth recorded subject according to annual age intervals from 7–8

longitudinally were analyzed in a group of untreated years to 15–16 years of age. The individual CVM stage

subjects according to different predetermined annual at the beginning of each annual age interval also was

(chronological) age intervals. Therefore, a full compar- identified. Finally, the annual age interval of maximum

ative diagnostic reliability analysis, including sensitiv- individual increment for each standing height, Co-Gn,

ity, specificity, positive and negative predictive Co-Goi, and mMG, was identified as the one displaying

values (PPVs and NPVs), and accuracy, of the CS3- the greatest increment of the whole series (ie, peak in

4 interval and the peak in statural height in the standing height and mandibular growth spurt) and

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

CVM, STANDING HEIGHT, AND MANDIBULAR GROWTH SPURT 601

peak) on the true-negative subjects (not undergoing the

mandibular growth spurt).

The Interactive Stats Calculator (http://ktclearing-

house.ca/cebm/practise/ca/calculators/statscalc) was

used to perform the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Results on the diagnostic reliability of the CVM stages

and standing height peak in the identification of the

mandibular growth spurt for each mandibular growth

parameter and according to each annual age interval

are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Since

very few peaks in any parameter were seen at 7–8-, 14–

15-, and 15–16-year annual age intervals (ie, very few

positive cases with almost all negative cases), these

intervals were not used for the diagnostic reliability

analysis. The number of cases in which peaks were

seen for each standing height, Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and

mMG, for the other age intervals ranged from 1 to 8.

Generally, the CS3-4 and standing height peak showed

Figure 1. Mandibular growth parameters. Identified landmarks: Co, similar behaviors, with a slightly better diagnostic

Condylion; Goi, Gonion Intersection; and Gn, Gnathion. Goi was reliability seen for Co-Goi and mMG, as compared to

defined as the point of intersection between the mandibular and

ramus planes.

that for Co-Gn, and for younger annual age intervals, as

compared to those for older age intervals.

By excluding the 9–10 years interval, for which all

subsequently was used for the diagnostic reliability the parameters were equal to 1, analyses regarding

analysis. For descriptive purposes, median CVM stage the CS3-4 yielded sensitivity values between 0.29 and

and means (6 standard deviations) of standing height, 1.0, specificity values between 0.63 and 1.0, PPVs

Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG were calculated according between 0.14 and 1.0 NPVs between 0.62 and 1.0,

to each annual age interval for females and males. and accuracy values between 0.71 and 0.95 (Table 1).

Analyses regarding the standing height peak yielded

Diagnostic Reliability Analysis sensitivity values between 0 and 0.88, specificity

Diagnostic reliability analysis included sensitivity, values between 0.63 and 1.0, PPVs between 0 and

specificity, PPVs, NPVs, and accuracy19 and was 1.0, NPVs between 0.62 and 1.0, and accuracy values

calculated for each annual age interval, while overall between 0.61 and 0.95 (Table 2).

PPVs were also calculated for the group as a whole. Overall PPVs of CS3-4 in the identification of Co-Gn,

This analysis evaluated the capability of the CS3-4 Co-Goi, and mMG were 0.63 (0.43–0.82), 0.75 (0.58–

interval or standing height peak in the identification of the 0.92), and 0.83 (0.68–0.98), respectively. Slightly

maximum individual increments of Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and lower overall PPVs were seen for the standing height

mMG. Each diagnostic parameter has been presented peak in the identification of Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG

as mean and 95% confidence interval. that were 0.50 (0.30–0.70), 0.58 (0.39–0.78), and 0.79

In particular, “sensitivity” is the probability that CS3-4 (0.63–0.95), respectively.

or standing height peak is present when the mandib- Detailed individual and median/mean data on the

ular growth spurt is taking place (true-positive rate); CVM stages and corresponding annual increments in

“specificity” is the probability that CS3-4 or standing standing height, Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mMG according

height peak is absent when the mandibular growth to the different annual age intervals are summarized in

the Appendix.

spurt is not present (true-negative rate); “accuracy”

represents the proportion of true results (both true

DISCUSSION

positive and true negative); and “PPV” is the proportion

of positive test subjects (positive for the CS3-4 or The diagnostic accuracy of the CVM method and of

standing height peak) on the true-positive subjects longitudinal measurements of standing height has

(undergoing the mandibular growth spurt). On the been based conjecturally on correlation analyses. For

contrary, “NPV” is the proportion of test-negative the first time, the diagnostic accuracy of both CVM

subjects (ie, negative for the CS3-4 or standing height interval CS3-4 and standing height peak in the

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

602 PERINETTI, CONTARDO, CASTALDO, McNAMARA, FRANCHI

Table 1. Diagnostic Reliability of the CS3-4 in the Identification of the Mandibular Growth Parameters Peaks According to Each Annual Age

Interval from 9 to 14 Yearsa

Age Intervals

Mandibular Diagnostic

Parameter Parameter 9–10 y 10–11 y 11–12 y 12–13 y 13–14 y

Co-Gn Sensitivity 1 0.71 (0.38–1.05) 1 1 0.29 (0–0.62)

Specificity 1 1 0.63 (0.39–0.86) 0.70 (0.50–0.90) 1

PPV 1 1 0.54 (0.27–0.81) 0.14 (0–0.40) 1

NPV 1 0.88 (0.73–1.04) 1 1 0.62 (0.35–0.88)

Accuracy 1 0.91 (0.79–1) 0.74 (0.56–0.92) 0.71 (0.52–0.91) 0.67 (0.43–0.91)

n, Peak (total) 2 (21) 7 (22) 7 (23) 1 (21) 7 (15)

Co-Goi Sensitivity 0.25 (0–0.67) 1 1 1 0.67 (0.13–1.2)

Specificity 0.94 (0.83–1) 0.88 (0.73–1) 0.80 (0.6–1) 0.80 (0.62–0.98) 1

PPV 0.50 (0–1) 0.71 (0.38–1) 0.73 (0.46–0.99) 0.20 (0–0.55) 1

NPV 0.84 (0.68–1) 1 1 1 0.92 (0.78–1)

Accuracy 0.81 (0.64–0.98) 0.91 (0.79–1) 0.87 (0.73–1) 0.81 (0.64–0.98) 0.93 (0.81–1)

n, Peak (total) 4 (21) 5 (22) 8 (23) 1 (21) 3 (15)

mMG Sensitivity 1 0.88 (0.65–1) 1 1 0.50 (0.01–0.99)

Specificity 0.95 (0.85–1) 1 0.80 (0.6–1) 0.85 (0.69–1) 1

PPV 0.50 (0–1) 1 0.73 (0.46–0.99) 0.25 (0–0.67) 1

NPV 1 0.93 (0.81–1) 1 1 0.85 (0.65–1)

Accuracy 0.95 (0.86–1) 0.95 (0.87–1) 0.87 (0.73–1) 0.86 (0.71–1) 0.87 (0.69–1)

n, Peak (total) 1 (21) 8 (22) 8 (23) 1 (21) 4 (15)

a

Data are presented as means (95% confidence intervals), with n 5 24 in each age interval; mMG indicates mean mandibular growth; CS3-4,

cervical vertebral maturation stages 3 and 4; Co, Condylion; Gn, Gnathion; Goi, Co–Gonion Intersection; PPV, positive predictive value; and

NPV, negative predictive value. Data on the extreme 7–8-, 14–15-, and 16–17-y intervals not shown.

identification of the mandibular growth spurt has been thy13,25 correlations. However, significant differences in

reported in the current study to range between 0.61 study design, cephalometric recordings, and data

and 0.95, depending primarily on the mandibular analysis have to be taken into account; comparisons

growth parameter used. of the conclusions of the above studies should be

Previous studies on growth indicators and on the undertaken with caution. In several other stud-

mandibular growth spurt have reported contrasting ies,7,12,14,23–25 the landmark Articulare was used instead

results of negligible,8,20–22 moderate,7,23,24 or notewor- of the landmark Condylion to assess the posterior end

Table 2. Diagnostic Reliability of the Standing Height Peak in the Identification of the Mandibular Growth Parameters Peaks According to Each

Annual Age Interval from 9 to 14 yearsa

Age Intervals

Mandibular Diagnostic

Parameter Parameter 9–10 y 10–11 y 11–12 y 12–13 y 13–14 y

Co–Gn Sensitivity 1 0.57 (0.20–0.94) 0.57 (0.20–0.94) 0 0.29 (0–0.62)

Specificity 1 0.87 (0.69–1) 0.63 (0.39–0.86) 0.90 (0.77–1) 1

PPV 1 0.67 (0.29–1) 0.40 (0.10–0.70) 0 1

NPV 1 0.81 (0.62–1) 0.77 (0.54–1) 0.95 (0.85–1) 0.62 (0.35–0.88)

Accuracy 1 0.77 (0.60–0.95) 0.61 (0.41–0.81) 0.86 (0.71–1) 0.67 (0.43–0.91)

n, Peak (total) 2 (21) 7 (22) 7 (23) 1 (21) 7 (15)

Co–Goi Sensitivity 0.25 (0–0.67) 0.80 (0.45–1) 0.75 (0.45–1) 0 0.67 (0.13–1)

Specificity 0.94 (0.83–1) 0.94 (0.83–1) 0.73 (0.51–0.96) 0.90 (0.77–1) 1

PPV 0.50 (0–1) 0.80 (0.45–1) 0.60 (0.30–0.90) 0 1

NPV 0.84 (0.68–1) 0.94 (0.83–1) 0.85 (0.65–1) 0.95 (0.85–1) 0.92 (0.78–1)

Accuracy 0.81 (0.64–0.98) 0.91 (0.79–1) 0.74 (0.56–0.92) 0.86 (0.71–1) 0.93 (0.81–1)

n, Peak (total) 4 (21) 5 (22) 8 (23) 1 (21) 3 (15)

mMG Sensitivity 1 0.75 (0.45–1) 0.88 (0.65–1) 0 0.50 (0.01–0.99)

Specificity 0.95 (0.85–1) 1 0.80 (0.60–1) 0.90 (0.77–1) 1

PPV 0.50 (0–1.19) 1 0.70 (0.42–0.98) 0 1

NPV 1 0.88 (0.71–1) 0.92 (0.78–1) 0.95 (0.85–1) 0.85 (0.65–1)

Accuracy 0.95 (0.86–1) 0.91 (0.79–1) 0.83 (0.67–0.98) 0.86 (0.71–1) 0.87 (0.69–1)

n, Peak (total) 1 (21) 8 (22) 8 (23) 1 (21) 4 (15)

a

Data are presented as means (95% confidence intervals), with n 5 24 in each age interval; mMG indicates mean mandibular growth; CS3-4,

cervical vertebral maturation stages 3 and 4; Co, Condylion; Gn, Gnathion; Goi, Co–Gonion Intersection; PPV, positive predictive value; and

NPV, negative predictive value. Data on the extreme 7–8-,14–15-, and 16–17-y intervals not shown.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

CVM, STANDING HEIGHT, AND MANDIBULAR GROWTH SPURT 603

point of the mandible. The problem with Articulare is be better identified by the growth indicators can be

that it is not an anatomical landmark that pertains to observed (Tables 1 and 2).

the mandible exclusively. Other reasons for conflicting According to the overall PPVs of the whole sample,

results among studies may reside in the repeatability 15, 18, and 20 out of 24 subjects (63%, 75%, and 83%,

for the CVM staging that was unsatisfactorily reported8 respectively) showed CS3-4 occurring at the beginning

or not reported at all.22 of the annual age interval where Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and

A recent longitudinal investigation by Engel and mMG, respectively, showed peaks. On the other hand,

coworkers8 reported poor capability of the CVM 12, 14, and 19 subjects (50%, 58%, and 79%,

method in the identification of the mandibular growth respectively) showed a standing height peak occurring

spurt. This investigation included skeletal Class II during the same age interval with Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and

females in whom the mandibular growth spurt is mMG peaks, respectively.

expected to be minimal.26 Moreover, this study8 used Overall, both the standing height peak and CS3-4

linear models according to annual age increments, in show a satisfactory capability in the identification of the

which the initial stage, rather than corresponding CVM

mandibular growth spurt (defined as Co-Goi or mMG

stages, of each interval was considered. Interestingly,

increments), with the mandibular growth spurt being

the present data indicated that when clustering

undiagnosed by these parameters in less than in one

subjects according to annual age intervals and sex

out of five subjects. Chronological age remains even

(see Appendix), the corresponding mean mandibular

less reliable according to previous4,28,29 and present

growth increments masked individual spurts as a result

of large variation in the age at which the pubertal spurt evidence. The mandibular growth spurt may occur very

occurred across subjects. early or late in several subjects (see Appendix),

In the current study, the Co-Goi spurt (ie, mandibular making the use of a determined age range22 unreliable.

ramus height), appears to be diagnosed more reliably Of note, fine transitional changes in the cervical

by both the CS3-4 interval and standing height peak as vertebral morphology may be responsible for determin-

compared to the Co-Gn spurt (ie, total mandibular ing a pubertal or nonpubertal stage; training is required

length; Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, the CS3-4 interval to assess CVM stages reliably, especially at stages

and standing height peak also appear to have a slightly CS4 and CS5.30 Although the mandibular growth spurt

better diagnostic capability in the identification of the has been seen herein to occur generally the year after

mMG spurt. The use of a combined parameter of the appearance of CS3, in some cases it may occur in

mandibular growth may have the advantage of taking the interval between CS4 and CS5 (Appendix). There-

into account the growth of the mandibular ramus as fore, a functional orthopedic treatment requiring the

well, thus overcoming some limitations intrinsic to inclusion of the mandibular growth spurt in the active

basic cephalometry.27 treatment period should last until attainment of CS5.

Generally, for each mandibular growth parameter, The present evidence thus is consistent with recent

and regardless of the annual age intervals, the meta-analyses showing the skeletal responses to

standing height peak and CS3-4 interval appeared to functional treatment of Class II malocclusion in pubertal

have similar specificity and sensitivity (Tables 1 and patients according to CVM staging.2,3,31

2). In addition, the accuracy was similar between these On the other hand, the use of the standing height

two growth indicators, but lower for the identification of requires several measurements repeated at regular

the Co-Gn spurt and greater for the mMG. However, intervals to construct an individual curve of growth

given the sample size and retrieved confidence

velocity, but it has the advantage of being noninvasive.

intervals used in the current study, a differential

From a clinical perspective, therefore, the recording of

behavior between these two growth indicators cannot

standing height may be useful when a recent head film

be excluded.

is not available or when CVM staging is unclear.

In the present study, NPVs generally were high. This

finding was due to the relatively large number of true- However, when CVM staging is unclear or unavailable,

negative cases in each annual age interval cluster. the use of further indicators, such as the middle

Therefore, when dealing with such a situation, an phalanx maturation method,32 may be indicated.

important diagnostic parameter is the PPV, which As a limitation, the present investigation was carried

gives an indication of the capability of a given growth out on a limited sample size from old data sets from the

indicator to identify the mandibular growth spurt, UMGS, from which the CVM method was partially

regardless of the number of true-negative cases. By derived.1 Nevertheless, provided herein is a simple

analyzing the PPVs in combination with the frequency procedure to elucidate the role of growth indicators in

distributions of the different mandibular growth param- the identification of mandibular growth spurts on an

eters, a general tendency for the Co-Goi and mMG to individual basis.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

604 PERINETTI, CONTARDO, CASTALDO, McNAMARA, FRANCHI

CONCLUSIONS 13. Gu Y, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular growth changes and

cervical vertebral maturation. a cephalometric implant study.

N The CS3-4 interval and the peak in standing height Angle Orthod. 2007;77:947–953.

show similar but variable accuracy in the identifica- 14. O’Reilly MT, Yanniello GJ. Mandibular growth changes and

maturation of cervical vertebrae—a longitudinal cephalo-

tion of the mandibular growth spurt that reaches

metric study. Angle Orthod. 1988;58:179–184.

satisfactory levels when the Co-Goi and mMG 15. Moore RN, Moyer BA, DuBois LM. Skeletal maturation and

increments are examined. craniofacial growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;

N Both the CS3-4 interval and standing height peak 98:33–40.

16. Perinetti G, Contardo L, Gabrieli P, Baccetti T, Di Lenarda R.

may be used in routine clinical practice to enhance

Diagnostic performance of dental maturity for identification

efficiency of treatments requiring the inclusion of the of skeletal maturation phase. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:

mandibular growth spurt in the active treatment period. 487–492.

17. Flores-Mir C, Burgess CA, Champney M, Jensen RJ,

Pitcher MR, Major PW. Correlation of skeletal maturation

REFERENCES stages determined by cervical vertebrae and hand-wrist

evaluations. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:1–5.

1. Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr. The cervical

18. Lamparski DG. Skeletal Age Assessment Utilizing Cervical

vertebral maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of Vertebrae [dissertation]. Pittsburgh, PA: The University of

optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopedics. Semin Pittsburgh; 1972.

Orthod. 2005;11:119–129. 19. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. Papers that report

2. Perinetti G, Primožič J, Furlani G, Franchi L, Contardo L. diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ. 1997;315:540–543.

Treatment effects of fixed functional appliances alone or 20. Ball G, Woodside D, Tompson B, Hunter WS, Posluns J.

in combination with multibracket appliances: a systematic re- Relationship between cervical vertebral maturation and

view and meta-analysis. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:480–492. mandibular growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.

3. Franchi L, Contardo L. Treatment Effects of Removable 2011;139:e455–e461.

Functional Appliances in Pre-Pubertal and Pubertal Class II 21. Beit P, Peltomaki T, Schatzle M, Signorelli L, Patcas R.

Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Evaluating the agreement of skeletal age assessment based

Controlled Studies. PLoS One. 2015; 28;10:e0141198. on hand-wrist and cervical vertebrae radiography.

4. Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, Ghiozzi B, Cozza P. The Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:838–847.

diagnostic performance of chronologic age in the assessment 22. Mellion ZJ, Behrents RG, Johnston LE Jr. The pattern of

of skeletal maturity. Progr Orthod. 2006;7:176–188. facial skeletal growth and its relationship to various common

5. Flores-Mir C, Nebbe B, Major PW. Use of skeletal indexes of maturation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.

maturation based on hand-wrist radiographic analysis as 2013;143:845–854.

a predictor of facial growth: a systematic review. Angle 23. Grave KC. Timing of facial growth: a study of relations with

Orthod. 2004;74:118–124. stature and ossification in the hand around puberty. Aust

6. Parent AS, Teilmann G, Juul A, Skakkebaek NE, Toppari J, Orthod J. 1973;3:117–122.

Bourguignon JP. The timing of normal puberty and the age 24. Tofani MI. Mandibular growth at puberty. Am J Orthod.

limits of sexual precocity: variations around the world, 1972;62:176–195.

secular trends, and changes after migration. Endocr Rev. 25. Fishman LS. Radiographic evaluation of skeletal maturation.

2003;24:668–693. A clinically oriented method based on hand-wrist films.

7. Soegiharto BM, Moles DR, Cunningham SJ. Discriminatory Angle Orthod. 1982;52:88–112.

ability of the skeletal maturation index and the cervical 26. Stahl F, Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr. Longitu-

vertebrae maturation index in detecting peak pubertal dinal growth changes in untreated subjects with Class II

growth in Indonesian and white subjects with receiver division 1 malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.

operating characteristics analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial 2008;134:125–137.

Orthop. 2008;134:227–237. 27. Bookstein FL. On the cephalometrics of skeletal change.

Am J Orthod. 1982;82:177–198.

8. Engel TP, Renkema AM, Katsaros C, Pazera P, Pandis N,

28. Fishman LS. Chronological versus skeletal age, an evalua-

Fudalej PS. The cervical vertebrae maturation (CVM)

tion of craniofacial growth. Angle Orthod. 1979;49:181–189.

method cannot predict craniofacial growth in girls with Class

29. Hagg U, Taranger J. Maturation indicators and the pubertal

II malocclusion. Eur J Orthod. 2015. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.

growth spurt. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:299–309.

1093/ejo/cju085

30. Perinetti G, Caprioglio A, Contardo D. Visual assessment

9. Franchi L, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular growth

of the cervical vertebral maturation stages: a study of

as related to cervical vertebral maturation and body height.

diagnostic accuracy and repeatability. Angle Orthod. 2013;

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:335–340.

84:951–956.

10. Mitani H, Sato K. Comparison of mandibular growth with other

31. Franchi L, Contardo L, Primožič J, Perinetti G. Clinical

variables during puberty. Angle Orthod. 1992;62:217–222. alteration of mandibular growth: what we know after 40 years.

11. Fudalej P, Bollen AM. Effectiveness of the cervical vertebral In: McNamara JA Jr, ed. The 40th Moyers Symposium:

maturation method to predict postpeak circumpubertal Looking Back … Looking Forward. Craniofacial Growth Series.

growth of craniofacial structures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Center for Human Growth and Development, University of

Orthop. 2010;137:59–65. Michigan. Ann Arbor, Mich: Needham Press; 2014:263–285.

12. Bishara SE, Jamison JE, Peterson LC, DeKock WH. 32. Perinetti G, Perillo L, Franchi L, Di Lenarda R, Contardo L.

Longitudinal changes in standing height and mandibular Maturation of the middle phalanx of the third finger and

parameters between the ages of 8 and 17 years. cervical vertebrae: a comparative and diagnostic agreement

Am J Orthod. 1981;80:115–135. study. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2014;17:270–279.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

CVM, STANDING HEIGHT, AND MANDIBULAR GROWTH SPURT 605

Appendix. The Individual Cervical Vertebral Maturation (CVM) Stages and Corresponding Following Annual Increments in Standing Height

(SH; in cm), Condylion (Co)–Gnathion (Gn), Co–Gonion Intersection (Goi), and Mean Mandibular Growth (mMG; in mm) According to Each

Annual Age Intervala

7–8 y 8–9 y

ID Sex CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG

1 F 1 6.9 3.3 0.3 1.8 2 5.3 2.4 1.5 1.9

2 F – – – – – 1 6.4 2.1 20.2 1.0

3 F – – – – – 1 6.3 1.7 0.4 1.1

4 F – – – – – – – – – –

5 F 1 7.0 2.6 20.4 1.1 2 7.0 4.7 5.0 4.9

6 F – – – – – 1 3.8 1.1 20.9 20.4

7 F – – – – – – – – – –

8 F – – – – – – – – – –

9 F 1 7.6 2.0 0.4 1.2 2 7.6 3.6 2.0 2.8

10 F – – – – – – – – – –

11 F – – – – – – – – – –

12 F – – – – – 1 5.1 2.7 0.9 1.8

13 F – – – – – – – – – –

14 F – – – – – – – – – –

15 F – – – – – – – – – –

16 M – – – – – 1 4.8 2.9 3.1 3.0

17 M – – – – – – – – – –

18 M – – – – – – – – – –

19 M – – – – – – – – – –

20 M – – – – – – – – – –

21 M – – – – – – – – – –

22 M – – – – – – – – – –

23 M – – – – – – – – – –

24 M – – – – – 1 5.1 1.5 0.4 1.0

Femalesa 1.0 7.2 6 0.4 2.6 6 0.7 0.1 6 0.4 1.4 6 0.4 1.0 5.9 6 1.3 2.6 6 1.2 1.2 6 1.9 1.9 6 1.7

Malesa – – – – – 1.0 5.0 6 0.2 2.2 6 1.0 1.8 6 1.9 2.0 6 1.4

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

606 PERINETTI, CONTARDO, CASTALDO, McNAMARA, FRANCHI

Appendix. Extended.

9–10 y 10–11 y

ID Sex CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG

1 F 3 6.3 2.9 2.3 2.6 4 10.4 6.4 5.4 5.9

2 F 2 5.1 4.1 1.2 2.6 3 5.7 4.8 3.0 3.9

3 F 2 5.1 1.9 1.1 1.5 3 10.2 4.8 3.0 3.9

4 F 1 8.3 0.7 1.3 1.0 2 7.6 3.0 2.4 2.7

5 F 3 9.5 4.8 2.4 3.6 4 6.3 0.6 1.9 1.2

6 F 2 5.7 3.0 2.4 2.7 3 9.7 3.9 4.2 4.1

7 F 1 5.0 2.5 2.4 2.4 2 4.2 2.0 2.6 2.3

8 F 1 7.6 2.8 20.8 1.0 2 5.3 2.9 1.1 2.0

9 F 3 8.3 4.0 2.8 3.4 4 4.4 1.6 0.8 1.2

10 F 1 5.7 2.8 1.0 1.9 2 5.1 0.3 20.2 0.1

11 F 1 2.5 1.8 2.0 1.9 2 2.3 0.5 0.1 0.3

12 F 2 7.0 2.1 1.8 1.9 3 8.3 4.1 3.4 3.8

13 F 1 4.5 1.2 20.6 0.3 2 3.4 0.7 0.9 0.8

14 F 1 5.1 1.4 20.5 0.5 2 5.7 6.1 2.4 4.2

15 F 1 7.0 2.7 4.3 3.5 2 8.9 4.3 1.4 2.9

16 M 2 5.4 1.6 1.0 1.3 3 7.0 4.5 2.0 3.3

17 M – – – – – 1 5.5 3.1 2.6 2.8

18 M – – – – – – – – – –

19 M – – – – – – – – – –

20 M 1 5.1 3.9 2.7 3.3 2 3.8 1.3 1.8 1.5

21 M 1 5.7 4.7 1.8 3.2 2 6.4 1.5 1.5 1.5

22 M 1 5.1 2.4 2.2 2.3 2 7.6 3.3 2.8 3.1

23 M 1 7.6 3.1 3.1 3.1 2 8.3 5.2 0.5 2.9

24 M 2 4.4 1.3 1.9 1.6 3 7.6 3.5 1.1 2.3

Femalesa 1 6.2 6 1.8 2.6 6 1.1 1.5 6 1.4 2.1 6 1.1 2 6.5 6 2.5 3.1 6 2.1 2.2 6 1.5 2.6 6 1.7

Malesa 1 5.6 6 1.1 2.8 6 1.3 2.1 6 0.7 2.5 6 0.9 2 6.6 6 1.5 3.2 6 1.4 1.8 6 0.8 2.5 6 0.7

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

CVM, STANDING HEIGHT, AND MANDIBULAR GROWTH SPURT 607

Appendix. Extended.

11–12 y 12–13 y

ID Sex CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG

1 F 5 5.7 3.6 2.1 2.8 – – – – –

2 F 4 4.7 1.6 0.4 1.0 5 7.6 2.6 1.6 2.1

3 F 4 6.3 2.6 2.2 2.4 5 3.8 0.6 1.0 0.8

4 F 3 11.8 6.2 3.6 4.9 4 5.1 1.2 1.1 1.2

5 F 5 1.3 3.3 2.2 2.7 – – – – –

6 F 4 6.3 5.5 0.7 3.1 5 5.0 0.0 1.3 0.6

7 F 3 6.7 3.8 2.9 3.3 4 9.5 3.7 2.0 2.8

8 F 3 8.9 4.2 2.6 3.4 4 1.3 3.6 1.7 2.6

9 F 5 1.3 1.2 2.4 1.8 – – – – –

10 F 3 6.6 3.1 2.1 2.6 4 7.6 2.4 1.4 1.9

11 F 3 7.6 4.9 1.7 3.3 4 1.9 2.0 1.0 1.5

12 F 4 2.5 2.5 2.1 2.3 5 1.2 3.5 2.5 3.0

13 F 3 14.0 3.3 4.4 3.8 4 6.3 2.2 21.5 0.4

14 F 3 9.5 3.0 2.8 2.9 4 3.8 1.6 0.8 1.2

15 F 3 10.2 3.9 3.6 3.8 4 3.2 2.4 0.9 1.7

16 M 4 3.2 3.6 0.2 1.9 5 3.3 2.1 0.9 1.5

17 M 2 5.1 2.1 3.0 2.5 3 7.0 5.3 0.5 2.9

18 M 1 3.6 4.3 2.4 3.3 2 5.2 4.2 3.3 3.8

19 M – – – – – 1 6.2 1.7 0.8 1.3

20 M 3 16.5 10.7 7.9 9.3 4 2.9 2.7 0.5 1.6

21 M 3 5.4 3.8 2.6 3.2 4 2.1 2.6 1.0 1.8

22 M 3 9.0 3.8 3.8 3.8 4 4.4 2.2 2.7 2.4

23 M 3 10.8 3.3 3.5 3.4 4 5.4 5.3 4.7 5.0

24 M 4 7.5 3.9 0.6 2.2 5 3.8 2.3 20.8 0.7

Femalesa 3.0 6.9 6 3.6 3.5 6 1.3 2.4 6 1.0 2.9 6 0.9 4.0 4.7 6 2.7 2.2 6 1.2 1.2 6 1.0 1.7 6 0.9

Malesa 3.0 7.6 6 4.4 4.4 6 2.6 3.0 6 2.4 3.7 6 2.4 4.0 4.5 6 1.6 3.2 6 1.4 1.5 6 1.7 2.3 6 1.4

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

608 PERINETTI, CONTARDO, CASTALDO, McNAMARA, FRANCHI

Appendix. Extended.

13–14 y 14–15 y

ID Sex CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG

1 F – – – – – – – – – –

2 F – – – – – – – – – –

3 F – – – – – – – – – –

4 F 5 2.3 1.3 0.4 0.8 – – – – –

5 F – – – – – – – – – –

6 F – – – – – – – – – –

7 F 5 3.0 3.0 1.4 2.2 – – – – –

8 F 5 1.2 1.5 0.2 0.8 – – – – –

9 F – – – – – – – – – –

10 F 5 4.6 3.7 2.7 3.2 – – – – –

11 F 5 3.2 1.1 1.2 1.2 – – – – –

12 F – – – – – – – – – –

13 F 5 4.4 3.4 3.5 3.5 – – – – –

14 F 5 5.7 1.5 1.3 1.4 – – – – –

15 F 5 1.8 3.0 2.3 2.7 – – – – –

16 M – – – – – – – – – –

17 M 4 8.0 8.0 6.8 7.4 5 2.1 1.7 3.0 2.4

18 M 3 7.5 4.5 3.5 4.0 4 2.9 1.9 2.6 2.2

19 M 2 6.3 3.0 2.8 2.9 3 9.7 2.8 3.4 3.1

20 M 5 4.6 2.1 1.1 1.6 – – – – –

21 M 5 2.1 6.5 3.2 4.9 – – – – –

22 M 5 2.5 4.4 2.5 3.4 – – – – –

23 M 5 2.6 3.5 1.8 2.6 – – – – –

24 M – – – – – – – – – –

Femalesa 5.0 3.3 6 1.5 2.3 6 1.1 1.6 6 1.1 2 6 1.1 – – – – –

Malesa 5.0 4.8 6 2.5 4.6 6 2.1 3.1 6 1.8 3.8 6 1.9 4.0 4.9 6 4.2 2.1 6 0.6 3.0 6 0.4 2.6 6 0.5

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

CVM, STANDING HEIGHT, AND MANDIBULAR GROWTH SPURT 609

Appendix. Extended.

15–16 y

ID Sex CVM SH Co-Gn Co-Goi mMG

1 F – – – – –

2 F – – – – –

3 F – – – – –

4 F – – – – –

5 F – – – – –

6 F – – – – –

7 F – – – – –

8 F – – – – –

9 F – – – – –

10 F – – – – –

11 F – – – – –

12 F – – – – –

13 F – – – – –

14 F – – – – –

15 F – – – – –

16 M – – – – –

17 M – – – – –

18 M 5 2.1 0.3 2.3 1.3

19 M 4 2.9 0.8 2.9 1.9

20 M – – – – –

21 M – – – – –

22 M – – – – –

23 M – – – – –

24 M – – – – –

Femalesa – – – – –

Malesa 4.5 2.5 6 0.6 0.6 6 0.4 2.6 6 0.4 1.6 6 0.4

a

Central tendency values, as median (CVM) or mean 6 standard

deviation. Data on the extreme 16–17-yr interval not shown. M

indicates male; F, female.

b

Bold type indicates maximum individual increments for standing

height, Co-Gn, Co-Goi, and mean mandibular growth (mMG).

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 86, No 4, 2016

You might also like

- Naini 2020Document1 pageNaini 2020druzair007No ratings yet

- Tricks of The Trade: A New Method of Active Tie-Back For Space ClosureDocument1 pageTricks of The Trade: A New Method of Active Tie-Back For Space Closuredruzair007No ratings yet

- Of Communication: Dental Nursing Essentials CPDDocument3 pagesOf Communication: Dental Nursing Essentials CPDdruzair007No ratings yet

- Faculty of General Dental Practice (Uk) Critical Appraisal PackDocument6 pagesFaculty of General Dental Practice (Uk) Critical Appraisal Packdruzair007No ratings yet

- Nasal Considerations With The Le Fort I Osteotomy: Enhanced CPD DO CDocument5 pagesNasal Considerations With The Le Fort I Osteotomy: Enhanced CPD DO Cdruzair007No ratings yet

- BSPD Clinical Holding Guidelines Final With Flow Chart 250416Document8 pagesBSPD Clinical Holding Guidelines Final With Flow Chart 250416druzair007No ratings yet

- Online Preparatory Course For The Morth ExamDocument4 pagesOnline Preparatory Course For The Morth Examdruzair007100% (1)

- 02nola02ainsertednolaquality PDFDocument1 page02nola02ainsertednolaquality PDFdruzair007No ratings yet

- How To Design and Set Up A Clinical Trial Part 2: Protocols and ApprovalsDocument5 pagesHow To Design and Set Up A Clinical Trial Part 2: Protocols and Approvalsdruzair007No ratings yet

- PH-01: Clinical Photography Criteria Checklist: Date: NameDocument3 pagesPH-01: Clinical Photography Criteria Checklist: Date: Namedruzair007No ratings yet

- AI-01: Alginate Impression Product Checklist: Date: ArchDocument1 pageAI-01: Alginate Impression Product Checklist: Date: Archdruzair007No ratings yet

- SM-01: Pouring Impressions Study Models Checklist: Date: Name: Practice: PositionDocument2 pagesSM-01: Pouring Impressions Study Models Checklist: Date: Name: Practice: Positiondruzair007No ratings yet

- PH-02: Clinical Photography Production Checklist: Date: NameDocument9 pagesPH-02: Clinical Photography Production Checklist: Date: Namedruzair007No ratings yet

- Instructions: Special Appointments LogDocument1 pageInstructions: Special Appointments Logdruzair007No ratings yet

- NOLA-03A: NOLA Disinfected and Packaged For Sterilization Quality ChecklistDocument1 pageNOLA-03A: NOLA Disinfected and Packaged For Sterilization Quality Checklistdruzair007No ratings yet

- Con-01: Treatment Consultation Checklist: Date: Name: Practice: PositionDocument1 pageCon-01: Treatment Consultation Checklist: Date: Name: Practice: Positiondruzair007No ratings yet

- 01 Nola 01 AasseminsertnolastepsDocument1 page01 Nola 01 Aasseminsertnolastepsdruzair007No ratings yet

- A Review of COVID-19 and The Implications For Orthodontic Provision in EnglandDocument8 pagesA Review of COVID-19 and The Implications For Orthodontic Provision in Englanddruzair007No ratings yet

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Screening Guide For OrthodontistsDocument4 pagesBody Dysmorphic Disorder: A Screening Guide For Orthodontistsdruzair007No ratings yet

- Clinical Final ExamDocument11 pagesClinical Final Examdruzair007No ratings yet

- BOS Covid-19 Orthodontic Emergencies Protocol FinalDocument6 pagesBOS Covid-19 Orthodontic Emergencies Protocol Finaldruzair007No ratings yet

- Recall Intervals and NICE GuidelinesDocument7 pagesRecall Intervals and NICE Guidelinesdruzair007No ratings yet

- Mental Disorders in Dental Practice A Ca PDFDocument4 pagesMental Disorders in Dental Practice A Ca PDFdruzair007No ratings yet

- OSCE Scope of The OSCE in The Assessment of ClinicDocument5 pagesOSCE Scope of The OSCE in The Assessment of Clinicdruzair007No ratings yet

- Leonardi 2010Document6 pagesLeonardi 2010druzair007No ratings yet

- Radiation ProtectionDocument11 pagesRadiation Protectiondruzair007No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Text Descriptive Tentang HewanDocument15 pagesText Descriptive Tentang HewanHAPPY ARIFIANTONo ratings yet

- VectorCAST QA Factsheet ENDocument2 pagesVectorCAST QA Factsheet ENChaos XiaNo ratings yet

- 4040 SERIES: Hinge (Pull Side) (Shown) Top Jamb (Push Side) Parallel Arm (Push Side)Document11 pages4040 SERIES: Hinge (Pull Side) (Shown) Top Jamb (Push Side) Parallel Arm (Push Side)Melrose FabianNo ratings yet

- Lab 6 Data VisualizationDocument8 pagesLab 6 Data VisualizationRoaster GuruNo ratings yet

- CN Blue Love Rigt Lyrics (Romanized)Document3 pagesCN Blue Love Rigt Lyrics (Romanized)Dhika Halet NinridarNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 HRM in PandemicDocument2 pagesCase Study 1 HRM in PandemicKristine Dana LabaguisNo ratings yet

- British Airways Culture and StructureDocument29 pagesBritish Airways Culture and Structure陆奕敏No ratings yet

- PS410Document2 pagesPS410Kelly AnggoroNo ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan Form 4 (Literature: "The Living Photograph")Document2 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan Form 4 (Literature: "The Living Photograph")Maisarah Mohamad100% (3)

- Beyond The Breech Trial. Maggie BanksDocument4 pagesBeyond The Breech Trial. Maggie Bankspurpleanvil100% (2)

- Po 4458 240111329Document6 pagesPo 4458 240111329omanu79No ratings yet

- Ninja 5e v1 5Document8 pagesNinja 5e v1 5Jeferson Moreira100% (2)

- FBDocument27 pagesFBBenjaminNo ratings yet

- Fluid Mechanics HydraulicsDocument420 pagesFluid Mechanics Hydraulicsanonymousdi3noNo ratings yet

- Topic 4 Statistic II (Form 3)Document2 pagesTopic 4 Statistic II (Form 3)Ct KursiahNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 (C) Innovation in EntrepreneurDocument36 pagesCHAPTER 2 (C) Innovation in EntrepreneurHuiLingNo ratings yet

- The Big M Method: Group BDocument7 pagesThe Big M Method: Group BWoo Jin YoungNo ratings yet

- M14 PManualDocument382 pagesM14 PManualnz104100% (2)

- Stamp 07 eDocument6 pagesStamp 07 eDumitru TuiNo ratings yet

- Homeopatia Vibracional RatesDocument45 pagesHomeopatia Vibracional RatesAugusto Bd100% (4)

- RTRT User GuideDocument324 pagesRTRT User GuideAlae Khaoua100% (3)

- SBU PlanningDocument13 pagesSBU PlanningMohammad Raihanul HasanNo ratings yet

- Pavlishchuck Addison - 2000 - Electrochemical PotentialsDocument6 pagesPavlishchuck Addison - 2000 - Electrochemical PotentialscomsianNo ratings yet

- Iso 27001 Requirementsandnetwrixfunctionalitymapping 1705578827995Document33 pagesIso 27001 Requirementsandnetwrixfunctionalitymapping 1705578827995Tassnim Ben youssefNo ratings yet

- Root End Filling MaterialsDocument9 pagesRoot End Filling MaterialsRuchi ShahNo ratings yet

- RG-RAP6260 (G) Hardware InstallationDocument26 pagesRG-RAP6260 (G) Hardware InstallationrazuetNo ratings yet

- 2 TolentinoDocument12 pages2 TolentinoMA. ANGELINE GRANADANo ratings yet

- Rotex GS Zero-Backlash Shaft CouplingDocument19 pagesRotex GS Zero-Backlash Shaft CouplingIrina DimitrovaNo ratings yet

- DbmsDocument5 pagesDbmsRohit KushwahaNo ratings yet