Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Infographic Antimicrobial Resistance 20140430

Uploaded by

Markus AbiogCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Infographic Antimicrobial Resistance 20140430

Uploaded by

Markus AbiogCopyright:

Available Formats

Outbreak Investigation Report

Lethal paralytic shellfish poisoning from

consumption of green mussel broth,

Western Samar, Philippines, August 2013

Paola Katrina Ching,ab Ruth Alma Ramos,ab Vikki Carr de los Reyes,b Ma Nemia Sucalditob and Enrique Tayagb

Correspondence to Paola Katrina Ching (e-mail: paolaching@gmail.com).

Background: In July 2013, the Philippines’ Event-Based Surveillance & Response Unit received a paralytic shellfish

poisoning (PSP) report from Tarangnan, Western Samar. A team from the Department of Health conducted an outbreak

investigation to identify the implicated source and risk factors in coastal villages known for green mussel production and

exportation.

Methods: A case was defined as a previously well individual from Tarangan, Western Samar who developed gastrointestinal

symptoms and any motor and/or sensory symptoms after consumption of shellfish from 29 June to 4 July 2013 in the

absence of any known cause. The team reviewed medical records, conducted active case finding and a case-control study.

Relatives of cases who died were interviewed. Sera and urine specimens, green mussel and seawater samples were tested

for saxitoxin levels using high performance liquid chromatography.

Results: Thirty-one cases and two deaths were identified. Consumption of >1 cup of green mussel broth was associated

with being a case. Seawater sample was positive for Pyrodinium bahamense var. compressum and green mussel samples

were positive for saxitoxin. Inspection revealed villagers practice open defecation and improper garbage disposal.

Conclusion: This PSP outbreak was caused by the consumption of the green mussel broth contaminated by saxitoxin. As

a result of this outbreak, dinoflagellate and saxitoxin surveillance was established, and since the outbreak, there have been

no harmful algal blooms event or PSP case reported since. A “Save Cambatutay Bay” movement, focusing on proper waste

disposal practice and clean-up drives has been mobilized.

H

armful algal blooms (HAB), commonly referred to The Philippines has the highest number of PSP

as “red tides”, can be caused by many microalgae cases reported in Asia5 with 2124 PSP cases and

such as the proliferation of Pyrodinium 120 deaths reported from 1983 to 2002. Green mussels

bahamense var. compressum (Pbc) dinoflagellate. (Pernavirides) and other bivalves were implicated for

HAB is predominant in tropical regions including the most cases. The first PSP outbreak was reported in the

Philippines, with Pbc dinoflagellate-producing saxitoxin Western Samar region in 1983, the same region as this

causing paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP). This outbreak. The health hazards and socioeconomic impact

neurotoxin is water-soluble, acid stable and relatively of this outbreak prompted the Philippine Government

heat stable even in high temperature.1 Toxin levels of to create the Toxic Red Tide Monitoring Programme in

120 to 180ug can produce moderate symptoms while 1984.

levels of 400 to 1060ug can cause human death.2 Within

5–30 minutes, perioral tingling and numbness extending Eutrophication, or excessive enrichment of nutrients

to face and neck can occur. Uncoordination, respiratory in the water, can stimulate algal blooms. Increased

difficulty and sensorium alteration are evident in severe phosphorous and nitrogen from sewage and agricultural

cases.3 Death can occur 1–12 hours after ingestion.4 run-off are conducive for phytoplankton production.

Gastrointestinal symptoms include vomiting, diarrhoea Many Filipinos residing in coastal areas are dependent

and abdominal cramps. on bodies of water for their income and survival.

a

Field Epidemiology Training Program, National Epidemiology Center, Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

b

Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

Submitted: 15 January 2015; Published: 8 May 2015

doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004

22 WPSAR Vol 6, No 2, 2015 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004 www.wpro.who.int/wpsar

Ching et al Paralytic shellfish poisoning from green mussels, Western Samar, Philippines

Cambatutay Bay, which surrounds Bahay and Gallego illness and were tested by the Marine Science Institute,

coastal villages in Tarangnan, is the primary source of University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City for

the community’s livelihood. It is well known for its green paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs) by precolumn oxidation

mussel farms and products like mussel chips, crackers high performance liquid chromatography.

and cookies. Tarangnan comprises 41 villages with a

population of 25 703. Environmental investigation

In July 2013, the Event-Based Surveillance & The team collected 500 ml of seawater and 30–40 green

Response Unit of the National Epidemiology Center mussel and oyster samples from three coastal areas

received a report of paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) with – Cambatutay Bay, Bahay village and Gallego village.

two deaths in Gallego village in Tarangnan, Western Samar. Green mussel samples were tested by the regional

A team from the Department of Health was sent to Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources using mouse

conduct an outbreak investigation to identify the bioassay. Marine Science Institute tested seawater

implicated source and to evaluate risk factors. and shellfish samples for saxitoxin and dinoflagellates

using pre-chromatographic oxidation reversed phase

METHODS high performance liquid chromatography equipped with

fluorescence detection.10

Epidemiological investigation

Investigators observed sanitation and food

A suspected case was defined as a previously well consumption practices in the two villages with the

individual from Tarangan, Western Samar who developed highest attack rates. Residents of the coastal areas were

gastrointestinal symptoms and any motor and/or sensory asked if algal blooms had been observed.

and gastrointestinal symptoms from 29 June to 4 July

2013 after consumption of shellfish in the absence of RESULTS

any known cause. A confirmed case had blood or urine

positive for saxitoxin. The outbreak response team Case characteristics

reviewed medical records of outpatients and admitted

patients at the local health centre and district hospital. A total of 31 cases were identified. The incubation period

Active case finding of communities from the two villages ranged from 1 hour to 23 hours (median 11 hours)

with reported cases was conducted. Relatives of recently with the first date of occurrence on 29 June 2013 and

deceased community members were interviewed. a peak on 1 July 2013 (Figure 1).Twenty-eight cases

(90%) reported circumoral and extremity numbness,

An unmatched case–control (1:3) study was 20 (65%) reported dizziness and 17 (55%) light

conducted. Controls were well individuals randomly headedness. Eight cases (26%) were hospitalized;

selected in the same or nearby households of the two two died (case fatality proportion = 6%). There

villages. They were excluded if they reported any motor, were 18 (58%) male cases; ages ranged from

sensory or gastrointestinal symptoms or tested positive 3 to 59 years (median = 26 years). The most affected

for saxitoxin. We used a standardized questionnaire to age groups were 21–30 years and 51–60 years (23%

collect data for cases and controls on demographics, each).

symptoms (except for controls), hygiene practices and

history of food consumption for the past three days. All cases reported consuming green mussels, either

We used EPI Info version 3.5.4 software for statistical raw, boiled or steamed; the total quantity ranged from

analysis and calculated odds ratios (OR) and confidence three to 50 (median = 15). Consumption of less than

intervals. Significant risk factors from bivariate analysis one cup up to six cups of broth were reported.

were then tested in multivariate analysis.

The two deaths were males, aged 3 and 50 years,

Laboratory investigation both from the same household. The older male died due

to cardiorespiratory arrest 15 hours after onset of illness.

Twenty-five urine and 100 blood specimens from cases He had eaten 50 green mussels, both raw and cooked.

and controls were collected one week after onset of The child was pronounced dead on arrival 10 hours after

www.wpro.who.int/wpsar WPSAR Vol 6, No 2, 2015 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004 23

Paralytic shellfish poisoning from green mussels, Western Samar, Philippines Ching et al

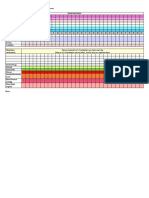

Figure. 1. PSP cases by date and time of onset, Tarangnan, Western Samar, Philippines, June to July 2013

(n = 31)

Death Cases

9

7

Number of cases

0

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

12:00 AM

12:00 PM

28-Jun 29-Jun 30-Jun 01-Jul 02-Jul 03-Jul 04-Jul 05-Jul

Date and time of onset of illness

PSP, Paralytic shellfish poisoning.

illness onset. He had consumed more than two cups of Environmental investigation

mussel broth. Previous medical histories for both cases

were unremarkable. We observed families practicing open defecation in the

hills, river and coastal areas. There was no organized

Caseăcontrol study garbage collection system; garbage was dumped

haphazardly in backyards and near coastal areas.

The case–control study comprised the 31 cases and The village captain reported that discoloration of the

93 controls. Bivariate analysis revealed several seawater surface was noticed by one of his constituents

significant risk factors: being male, harvesting their own in early June.

food, eating raw foods, consuming at least one cup of

mussel broth and consuming at least 15 green mussels. We did not observe discoloration of surface waters

Interestingly, carbonated beverages were inversely in Cambatutay Bay during sample collection. However,

associated with being a case (Table 1). However, only seawater samples collected four metres below the

a small number of study participants (four cases and surface had a reddish discoloration.

two controls) drank carbonated beverages. After

multivariate analysis, consumption of at least one cup DISCUSSION

of green mussel broth emerged as the only significant

association (OR: 12.0; 95% confidence interval: This PSP outbreak was caused by consumption of green

2.1–63.2). mussels, specifically as a mussel broth, harvested in

Cambatutay Bay in Tarangnan, Western Samar. High

Laboratory examination toxicity of saxitoxin was found in both green mussel

and seawater samples and cases primarily presented

Saxitoxins and Pbc dinoflagellates were detected with neurological symptoms consistent with other PSP

in the three water samples. The green mussel and outbreaks.6

oysters specimens had PSTs at levels higher than the

international regulatory limit. The 100 human serum Consuming at least one cup of broth was identified

and 25 urine samples were negative for PSTs. as a risk factor for illness. Saxitoxins are known to be

24 WPSAR Vol 6, No 2, 2015 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004 www.wpro.who.int/wpsar

Ching et al Paralytic shellfish poisoning from green mussels, Western Samar, Philippines

Table 1. Factors associated with PSP, Tarangnan, Western Samar, Philippines, June to July 2013

Characteristics Case n (%) Control n (%) Crude OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI)

Sex

Male 18 (58) 33 (36) 2.5 (1.1–5.7) –

Female 13 (42) 59 (64) –

Consumption of mussel broth

1 cup or more 13 (42) 8 (10) 7.6 (2.5–23.9) 12.0 (2.1–63.2)

Less than 1 cup 18 (58) 84 (90) –

Food source

Harvested 18 (58) 24 (26) 3.9 (1.6–10.2) –

Bought 13 (42) 69 (74)

Type of foods eaten

Raw 27 (87) 44 (47) 7.5 (2.3–27.7) –

Cooked 4 (13) 49 (53) –

Consumption of mussels

1 mussel 0 (0) 2 (2) 0 (0–12.7) –

2–4 mussels 0 (0) 8 (9) 0 (0–1.8)

5–10 mussels 1 (3) 13 (14) 0.2 (0.01–1.6)

11–14 mussels 2 (6) 21 (23) 0.2 (0.04–1.2)

15 or more 28 (90) 49 (53) 8.4 (2.2–37.3)

Consumption of carbonated beverages

Yes 4 (0.1) 2 (0) 0.1 (0.0–0.9)

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PSP, paralytic shellfish poisoning.

heat stable in shellfish at a temperature of 100 °C limited testing yield as saxitoxins are only excreted in

in household processing and therefore can dissipate the urine eight hours after ingestion.10 Third, the team

from green mussels into boiling water and become arrived a week after the outbreak which possibly hindered

concentrated in broths.7 In another outbreak, a butter testing of active and symptomatic cases. However, we

clam broth was found to have high saxitoxin levels,8 were able to identify the source of this outbreak from

further supporting that boiling shellfish in water cannot both epidemiological and environmental results.

destroy the toxin.

As a response to the outbreak, we recommended

Another observation from the environmental to the local government of Tarangan the banning of

investigation was poor sanitation practices of the harvesting shellfish in Cambatutay Bay. Cambatutay

villagers. Open defecation and garbage disposal in the Bay was also added as a sentinel site for dinoflagellate

coastal areas may have contributed to water pollution. and saxitoxin monitoring. A “Save Cambatutay Bay”

Dumping of raw sewage makes more nutrients available movement was created and core group members were

for dinoflagellates and can increase occurrence of mobilized in the community. This campaign focused on

HAB.9 proper waste disposal practices and clean-up drives.

There have been no HAB events or PSP cases since the

This study has some limitations. First, there was outbreak stopped.

no green mussel left over from the implicated meals

for testing. Second, while there were human serum Conflicts of interest

specimens available for saxitoxin testing, delays in

specimen collection and reagent availability may have None declared.

www.wpro.who.int/wpsar WPSAR Vol 6, No 2, 2015 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004 25

Paralytic shellfish poisoning from green mussels, Western Samar, Philippines Ching et al

Funding standards.gov.au/publications/documents/TR14.pdf, accessed

20 April 2015).

3. Kao CY. Paralytic shellfish poisoning. In: Falconer IR (ed), Algal

This foodborne outbreak investigation was funded by the Toxins in Seafood and Drinking Water. London, Academic Press,

Department of Health, Philippines. 1993.

4. Rodriguez DC et al. Lethal paralytic shellfish poisoning in

Acknowledgements Guatemala. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and

Hygiene, 1990, 42:267–271. pmid:2316796

5. Azanza RV, Taylor FJ. Are Pyrodinium blooms in the Southeast

We are grateful for the support of the Center for Health Asian region recurring and spreading? A view at the end of the

and Development-Eastern Visayas, Samar Provincial millennium. Ambio, 2001, 30:356–364. pmid:11757284

Health Office, the Local Government Unit of Tarangnan, 6. Hurley W et al. Paralytic shellfish poisoning: a case series. The

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2014, 15:378–381.

Tarangnan Municipal Health Office and the residents doi:10.5811/westjem.2014.4.16279 pmid:25035737

during the field investigation. We are also thankful for 7. Alexander J et al. Marine biotoxins in shellfish-Saxitoxin group.

Christopher Mendoza of the Marine Science Institute for EFSA Journal, 2009, 1019:1–76.

the laboratory examinations. 8. State of Alaska Epidemiology. Paralytic shellfish poisoning-Alaska

Peninsula, Kodiak. Bulletin No. 10, July 3, 1990. Juneau,

State of Alaska, 1990 (http://www.epi.hss.state.ak.us/bulletins/

References docs/b1990_10.htm, accessed 24 April 2015).

1. Hughes JM, Merson MH. Current concepts fish and shellfish 9. Gessner BD, Middaugh JP. Paralytic shellfish poisoning in Alaska: a

poisoning. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1976, 20-year retrospective analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology,

295: 1117–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJM197611112952006 1995, 141:766–770. pmid:7709919

pmid:988478 10. García C et al. Human intoxication with paralytic shellfish toxins:

2. Shellfish toxins in foods: a toxicological Review and risk clinical parameters and toxin analysis in plasma and urine.

assessment. Technical Report Series No. 14. Canberra, Biological Research, 2005, 38:197–205. doi:10.4067/S0716-

Australia New Zealand Food Authority, 2001 (http://www.food 97602005000200009 pmid:16238098

26 WPSAR Vol 6, No 2, 2015 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.1.004 www.wpro.who.int/wpsar

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Fruits Vegetables and HerbsDocument448 pagesFruits Vegetables and HerbsRaluca Dragomir96% (28)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Withholding The TruthDocument6 pagesWithholding The TruthAngel Beltran CastroNo ratings yet

- Intro To MycologyDocument8 pagesIntro To Mycologycamille chuaNo ratings yet

- Fluid and ElectrolytesDocument179 pagesFluid and ElectrolytesTrixie Al Marie75% (4)

- Reading Test 6 OETDocument23 pagesReading Test 6 OETRancesh FamoNo ratings yet

- Reflexology Manual VTCTDocument151 pagesReflexology Manual VTCTAhmad Mehdi100% (1)

- Matary General Surgery 2013Document309 pagesMatary General Surgery 2013Raouf Ra'fat Soliman100% (8)

- Reiki Medical Presentation: Click HereDocument8 pagesReiki Medical Presentation: Click HereSuresh NarenNo ratings yet

- MedicinMan June 2012 IssueDocument20 pagesMedicinMan June 2012 IssueAnup SoansNo ratings yet

- A To Z Orthodontics MCQDocument112 pagesA To Z Orthodontics MCQUjjwal Pyakurel100% (4)

- Terramycin - Drug StudyDocument2 pagesTerramycin - Drug StudyBolasoc, HazelNo ratings yet

- Medical Director, VP of Medical Affairs, VP of Regulatory AffairDocument5 pagesMedical Director, VP of Medical Affairs, VP of Regulatory Affairapi-121422030No ratings yet

- Cancers 13 01521 v2Document20 pagesCancers 13 01521 v2Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- DNA Barcoding As A Tool For Coral Reef ConservatioDocument14 pagesDNA Barcoding As A Tool For Coral Reef ConservatioRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Molecular Identification Methods of Fish Species RDocument30 pagesMolecular Identification Methods of Fish Species RRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Ulfah 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 674 012032Document6 pagesUlfah 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 674 012032Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Yusup 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 429 012046Document9 pagesYusup 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 429 012046Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer ResearchDocument23 pagesJournal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer ResearchRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Exercises On DefinitionDocument1 pageExercises On DefinitionRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello, Rhaiza P. April 28, 2020 Internet Exercise C1A1-YDocument3 pagesPabello, Rhaiza P. April 28, 2020 Internet Exercise C1A1-YRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- 4 - Clinical Cancer ResearchDocument4 pages4 - Clinical Cancer ResearchRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Current and Resistance ExerciseDocument2 pagesCurrent and Resistance ExerciseRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- War of CurrentsDocument2 pagesWar of CurrentsRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- DAILY MOOD CHART: MONTH OF - : High +3 +2 +1Document2 pagesDAILY MOOD CHART: MONTH OF - : High +3 +2 +1Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- DOST Scholarship FormDocument3 pagesDOST Scholarship FormRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- HW#P 3Document1 pageHW#P 3Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismDocument1 pagePabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Role of Humanities and The Arts in 21st Century EducationDocument2 pagesThe Role of Humanities and The Arts in 21st Century EducationRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello - ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceDocument3 pagesPabello - ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Rhaizappabello : U260126Ftwr1Smdc Sunresidencesmayonst 1114quezoncityDocument6 pagesRhaizappabello : U260126Ftwr1Smdc Sunresidencesmayonst 1114quezoncityRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello, Rhaiza P. WS 10:30 AM - 12:00 NN HUM SEPTEMBER 14, 2019 Artistic Periods A. Ancient ArtDocument3 pagesPabello, Rhaiza P. WS 10:30 AM - 12:00 NN HUM SEPTEMBER 14, 2019 Artistic Periods A. Ancient ArtRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- BEDocument4 pagesBERhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Dialogue On Medical Surgical NursingDocument3 pagesDialogue On Medical Surgical NursingAnonymous XEV3a17n3YNo ratings yet

- Emergency Room Rotation Requirements: Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaDocument12 pagesEmergency Room Rotation Requirements: Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaMarco BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Automation in MicrobiologyDocument63 pagesAutomation in Microbiologytummalapalli venkateswara raoNo ratings yet

- 4 Precision Attachments For Partial DenturesDocument18 pages4 Precision Attachments For Partial DenturespriyaNo ratings yet

- FreeStyle Libre Pro Patient BrochureDocument2 pagesFreeStyle Libre Pro Patient BrochureAdvaitNo ratings yet

- Barangay Sta. Cruz Profile 2014Document12 pagesBarangay Sta. Cruz Profile 2014Donnabelle NazarenoNo ratings yet

- SDS N Butanol Rev4Document15 pagesSDS N Butanol Rev4agadeilagaNo ratings yet

- Life Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenDocument5 pagesLife Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenAsia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary ResearchNo ratings yet

- Health InsuranceDocument11 pagesHealth InsurancedishaNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing: Rifadin RifampinDocument4 pagesCollege of Nursing: Rifadin RifampinAnika PleñosNo ratings yet

- The Neutral Zone Concept in Complete DentureDocument122 pagesThe Neutral Zone Concept in Complete Denturevahini niharikaNo ratings yet

- LINEE GUIDA ERC 2021 - Capitolo 7 - Terapia Post RianimazioneDocument114 pagesLINEE GUIDA ERC 2021 - Capitolo 7 - Terapia Post Rianimazionegiuseppe.tancredi.scarioNo ratings yet

- Common Craniofacial Anomalies. Conditions of Craniofacial AtrophyHypoplasia and NeoplasiaDocument14 pagesCommon Craniofacial Anomalies. Conditions of Craniofacial AtrophyHypoplasia and NeoplasiaPaola LoloNo ratings yet

- Enneagram in Psychological Assessment PDFDocument9 pagesEnneagram in Psychological Assessment PDFo8o0o_o0o8o2533No ratings yet

- Eichel (2020), Antimicrobial Effects of Mustard Oil-Containing Plants Against Oral Pathogens: An in Vitro StudyDocument7 pagesEichel (2020), Antimicrobial Effects of Mustard Oil-Containing Plants Against Oral Pathogens: An in Vitro StudyPhuong ThaoNo ratings yet

- LlageriDocument8 pagesLlageriBlodin ZylfiuNo ratings yet

- The 5 R'S: An Emerging Bold Standard For Conducting Relevant Research in A Changing WorldDocument9 pagesThe 5 R'S: An Emerging Bold Standard For Conducting Relevant Research in A Changing WorldFotachi IrinaNo ratings yet

- WI Medication AdministrationDocument11 pagesWI Medication AdministrationVin BitzNo ratings yet