Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Systematic Review With Meta Analysis The Prevalence of Bile Acidmalabsorption in The Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Dia

Systematic Review With Meta Analysis The Prevalence of Bile Acidmalabsorption in The Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Dia

Uploaded by

Patricia GalindoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Systematic Review With Meta Analysis The Prevalence of Bile Acidmalabsorption in The Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Dia

Systematic Review With Meta Analysis The Prevalence of Bile Acidmalabsorption in The Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Dia

Uploaded by

Patricia GalindoCopyright:

Available Formats

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics

Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of bile acid

malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea

S. A. Slattery*, O. Niaz†, Q. Aziz*, A. C. Ford‡,§,1 & A. D. Farmer*,¶,1

*Neurogastroenterology Group, Blizard SUMMARY

Institute of Cell & Molecular Science,

Wingate Institute of

Neurogastroenterology, Barts & the

Background

London School of Medicine & Irritable bowel syndrome is a widespread disorder with a marked socioeco-

Dentistry, Queen Mary University of nomic burden. Previous studies support the proposal that a subset of

London, London, UK. patients with features compatible with diarrhoea-predominant IBS (IBS-D)

†

Blackpool Victoria Hospital,

have bile acid malabsorption (BAM).

Blackpool, UK.

‡

Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St.

James’s University Hospital, Leeds, Aim

UK. To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the prevalence

§

Leeds Institute of Biomedical and

of BAM in patients meeting the accepted criteria for IBS-D.

Clinical Sciences, Leeds University,

Leeds, UK.

¶

Department of Gastroenterology, Methods

University Hospitals of the North MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched up to March 2015. Studies recruit-

Midlands, Stoke on Trent, UK. ing adults with IBS-D, defined by the Manning, Kruis, Rome I, II or III cri-

1

teria and which used 23-seleno-25-homotaurocholic acid (SeHCAT) testing

Joint senior authors.

for the assessment of BAM were included. BAM was defined as 7 day SeH-

CAT retention of <10%. We calculated the rate of BAM and 95% confi-

Correspondence to: dence intervals (CI) using a random effects model. The methodological

Dr A. D. Farmer, Wingate Institute of quality of included studies was evaluated using the Quality Assessment for

Neurogastroenterology, 26 Ashfield Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2).

Street, London E1 2AJ, UK.

E-mail: a.farmer@qmul.ac.uk

Results

The search strategy identified six relevant studies comprising 908 individu-

Publication data als. The rate of BAM ranged from 16.9% to 35.3%. The pooled rate was

Submitted 12 March 2015 28.1% (95% CI: 22.6–34%). There was significant heterogeneity in effect

First decision 23 March 2015

Resubmitted 10 April 2015

sizes (Q-test v2 = 17.9, P < 0.004; I2 = 72.1%). The type of diagnostic crite-

Accepted 10 April 2015 ria used or study country did not significantly modify the effect.

EV Pub Online 27 April 2015

Conclusions

As part of AP&T’s peer-review process, a These data provide evidence that in excess of one quarter of patients meet-

technical check of this meta-analysis

was performed by Dr Y. Yuan. This

ing accepted criteria for IBS-D have bile acid malabsorption. This distinc-

article was accepted for publication after tion has implications for the interpretation of previous studies, as well as

full peer-review. contemporaneous clinical practice and future guideline development.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 3

doi:10.1111/apt.13227

S. A. Slattery et al.

INTRODUCTION In 2009, Wedlake et al. systematically reviewed the lit-

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterised by abdom- erature to evaluate the prevalence of BAM in patients with

inal pain and alteration in bowel habit in the absence of a chronic diarrhoea, identifying 18 studies, containing 1223

structural or biochemical abnormality.1 IBS is a wide- patients, and demonstrated that 32% of individuals had

spread disorder with a reported global prevalence of >10% BAM, defined as a SeHCAT retention of <10%.10 How-

and has a marked socioeconomic burden.2, 3 IBS is also ever, this review was subject to a number of limitations.

associated with a significant diminution in work produc- Firstly, it only reported the crude pooled rate of BAM,

tivity and health related quality of life.4 The pathophysiol- rather than weighted rates. Secondly, it included patients

ogy of IBS is incompletely understood and to date a that had ‘chronic or recurrent diarrhoea’, ‘watery diar-

clinically applicable biomarker remains elusive.5 There is rhoea’, ‘diarrhoea of an IBS-D nature’ ‘or abdominal pain

marked inter-individual variability in the presentation, and no recognised organic pathology’ rather than utilising

natural history and response to treatment of IBS,6 leading the accepted definitions.16 Moreover, since this systemic

to the postulation that, despite internationally accepted review, several new reports have been published. The aim

classifications, a number of distinct pathophysiological of our study was to address these knowledge gaps by per-

entities may exist.7 With respect to diarrhoea, pre-domi- forming an updated systemic review with meta-analysis of

nant IBS (IBS-D) two lines of evidence support this pro- the current literature assessing the prevalence of BAM in

posal. Firstly, >30% of individuals who are exposed to a patients with IBS-D using accepted criteria, reasoning that

bacterial gastroenteritis develop chronic symptoms consis- the prevalence of BAM in those previously diagnosed with

tent with a diagnosis of IBS-D, termed post-infectious IBS-D may be less than previously reported.

IBS.8, 9 Secondly, idiopathic bile acid malabsorption

(BAM) may account for a proportion of patients with fea- METHODS

tures that are clinically indistinguishable from IBS-D.10

Synthesised in the liver, bile acids play a pivotal role Search strategy and study selection

in the absorption of dietary fats and are excreted into This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed

the small intestine via the biliary tree. Within the small in accordance with PRISMA recommendations.17 A liter-

intestine, bile acids coalesce with dietary fats to form ature search was performed using MEDLINE (1980–

micelles, of which approximately 95% are actively reab- March 2015) and EMBASE (1980–March 2015). Studies

sorbed in the terminal ileum and are returned to the were searched for using the terms irritable bowel syn-

liver via the enterohepatic circulation, with the remain- drome, functional bowel disorder, functional diarrhoea,

der lost via faecal output.11, 12 BAM may occur as a chronic diarrhoea, bile acid diarrhoea, primary bile acid

sequelae of a defect of bile acid reabsorption in the distal diarrhoea, as medical subject heading (MeSH) and free

small bowel such that they reach the colon. In the colon, text terms. These were combined with the set operator

bile acids undergo both dehyroxylation and deconjuga- ‘AND’ with following terms: bile acid malabsorption, bile

tion, where they then exert pro-secretory actions leading salt malabsorption, SeHCAT,23-seleno-25-homotaurochol-

to diarrhoea, defaecatory urgency, bloating and abdomi- ic acidas free text terms. Publications were restricted to

nal discomfort.13 Although there is no universally those studying adult populations, defined as greater than

accepted gold standard modality for diagnosing BAM, 16 years old, with a documented diagnosis of IBS-D

23-seleno-25-homotaurocholic acid (SeHCAT) testing is according to accepted criteria, i.e.IBS-D based on one of

widely used in Europe. Homotaurocholic acid is a syn- the following accepted international criteria; (i) Manning

thetic analogue of the naturally occurring conjugated bile criteria, (ii) Kruis criteria, (iii) Rome 1, (iv) Rome II or

acid, taurocholic acid. Following oral administration of a (v) Rome III. BAM was defined as SeHCAT retention of

standardised dose of selenium-75-homocholic acid tau- <10% at 7 days.The bibliographies of all eligible studies

rine, the retained fraction is assessed using a gamma that were identified were also comprehensively searched

camera at 1 week, with values of less that 15%, 10% and for studies not identified using the initial search strategy.

5% being considered to represent mild, moderate and Furthermore, the abstract books from four conference

severe BAM respectively.14 Three distinct types of BAM proceedings (Digestive Disease Week, United European

have been described: type 1 – secondary to terminal ileal Gastroenterology Week, the British Society of Gastroen-

disease or surgery, type II – primary (or idiopathic) and terology and the Joint International Neurogastroenterolo-

type III – secondary to previous cholecystectomy, peptic gy and Motility meetings) between 1994 and 2014 were

ulcer surgery, coeliac disease or diabetes mellitus.15 searched by hand to identify any potentially eligible

4 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Systematic review with meta-analysis: bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D

studies published in abstract forms. Foreign language quently retrieved for detailed assessment. For two cita-

papers were translated where required. Where data were tions,21, 22 we successfully contacted the senior author

missing from the publication, the first and/or senior to clarify the inclusion criteria data. Of the 128 relevant

author was contacted to supply further information. citations, 122 were excluded as they did not meet the

Studies were independently evaluated by two investiga- inclusion criteria of the systematic review, thus leaving

tors (SMS and ADF) using predesigned eligibility forms; 6 eligible studies of 908 individuals for the IBS-D

according to theaforementioned eligibility criteria. Dis- analysis (Figure 1).

agreements were resolved by consensus.

Prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D

Outcome assessment patients

Data extraction. The name of the first author, year of There were six studies that reported the prevalence of

publication, number of subjects, type of internationally BAM based upon a positive SeHCAT study of 10% at

accepted definition of IBS-D, study design and outcomes 7 days in patients with IBS-D as defined by accepted cri-

regarding SeHCAT measures were recorded in a standar- teria. The crude pooled rate of BAM in IBS-D patients

dised fashion utilising an Excel spreadsheet (Excel for was 266/908 (29.3%), with rates varying from 16.9% to

Mac 2011; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). 35.3% (Table 1). The pooled rate was 28.1% (95% CI:

22.6–34%) by the random effects model (Figure 2).

Study methodological quality. The quality of the studies There was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes (Q-test

identified was assessed using Quality Assessment of v2 = 17.9, P < 0.004; I2 = 72.1%).

Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)-2 tool.18

Effect modification by diagnostic criteria used

Data synthesis and statistical analysis. Data were pooled Of the six studies that met the inclusion criteria, 4 stud-

using a random effects model, using DerSimonian-Laird ies used the Rome III definition, one study used Rome II

weights,19 as this was considered the most plausible meth- and 1 study used the Rome I. No studies utilised the

odology given previously reported heterogeneity.10 The Kruis criteria. The pooled rate for prospective studies

diversity of study results within a meta-analysis can be using the Rome III criteria was 25.0% (95% CI: 11.3–

evaluated using statistical tests of heterogeneity, the 41.9%) by the random effects model (Figure 3). There

Cochran’s Q and I² statistic, there by assessing whether was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes (Q-test

the variation across component studies is due to true het- v2 = 11.4, P < 0.0001, I2 = 91.2%).

erogeneity or by chance. Cochran’s Q is distributed as a

chi-square statistic and the I² statistic describes the per- Effect modification by country

centage of variation across studies, that is due to heteroge- Of the 6 studies that met the inclusion criteria, 5 studies

neity rather than chance with values ranging from 0% to were performed in the UK and 1 in Sweden. The pooled

100%, with 0% representing no observed heterogeneity rate in UK studies was 28.7% (95% CI: 22.5–35.4%) by

and with increasing values indicating increasing heteroge- the random effects model (Figure S1). There was signifi-

neity. A value less than 25% was chosen to represent low cant heterogeneity in effect sizes (Q-test v2 = 16.9,

levels of heterogeneity.20 We aimed to perform the follow- P = 0.002; I2 = 76.3%).

ing pre-specified subgroup analyses: (i) effect modification

by diagnostic criteria used, (ii) effect modification by Effect modification by study design

county and (iii) effect modification by study design. The Of the 6 studies, 4 were prospective. The pooled rate

meta-analysis was performed using Statsdirect (Version was 27.2% (95% CI: 19.7–35.4%) by the random effects

V.2.7.2; StatsDirect, Sale, Cheshire, England) and was model (Figure S2). There was significant heterogeneity in

used for the generation of Forest plots for the stated effect sizes (Q-test v2 = 14.5, P = 0.002; I2 = 79.4%).

outcomes.

Study methodological quality assessment

RESULTS The methodological quality of the included studies is

summarised in Table 2. The overall quality of the

Search results included studies was high. The subject selection method

The search strategy returned 3391 citations of which may have introduced high bias in two studies, as the

168 appeared to be relevant. Full texts were subse- index standard, in this case the Rome criteria, was

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11 5

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S. A. Slattery et al.

23 studies identified

4042 studies identified 492 studies identified

through conference

through Pubmed search through Embase search

abstract search

1166 duplicate studies

4557 studies identified

excluded

3263 studies

3391 studies screened

excluded

122 studies full text

excluded:

88 did not use accepted

128 studies full text

criteria for IBS-D

assessed for eligibility

20 did not report/use

SeHCAT retention

14 age ranges were

not clear

6 studies included in

qualitative synthesis

Figure 1 | Flow diagram for

the assessment of studies

6 studies included in

quantitative synthesis identified in the systematic

(meta-analysis) review.

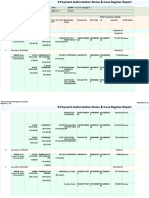

Table 1 | The details of the six studies, which included 908 patients, that met the inclusion criteria, which were

included in the meta-analysis

Numbers of patients with

Study Total number SeHCAT retention Crude Definition

Study Name Year design of patients <10% at 7 days pooled rate used Country

Smith et al.23 2000 P 193 65 33.6% Rome I UK

Kurien et al.24 2011 R 102 36 35.3% Rome III UK

Gracie et al.21 2012 R 143 35 24.5% Rome III UK

Dhaliwal et al.22 2013 P 288 95 33.0% Rome III UK

Bajor et al.25 2014 P 64 15 23.4% Rome II Sweden

Aziz et al.26 2014 P 118 20 16.9% Rome III UK

Totals 4P, 2R 908 266 29.3%

P, prospective study; R, retrospective study.

applied retrospectively. Four out of the six studies identi- DISCUSSION

fied were performed in tertiary care centres, which may In excess of 28% of patients meeting internationally

therefore limit the external validity, especially towards accepted criteria for IBS-D, have SeHCAT results consis-

primary and general secondary care populations. tent with BAM. This effect size was not modified by

6 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Systematic review with meta-analysis: bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D

Proportion meta-analysis plot [random effects]

Smith 2000 0.34 (0.27, 0.41)

Kurien 2011 0.35 (0.26, 0.45)

Gracie 2012 0.24 (0.18, 0.32)

Dhaliwal 2013 0.33 (0.28, 0.39)

Figure 2 | A Forest plot of the Bajor 2014 0.23 (0.14, 0.36)

pooled proportions of BAM in

908 patients with IBS-D. The Aziz 2015 0.17 (0.11, 0.25)

overall pooled proportion of

BAM in patients with IBS-D Combined 0.28 (0.23, 0.34)

was 28.1% (95% CI: 22.6–

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

34%).

Proportion (95% confidence interval)

Proportion meta-analysis plot [random effects]

Dhaliwal 2013 0.33 (0.28, 0.39)

Aziz 2015 0.17 (0.11, 0.25)

Figure 3 | A Forest plot of the Combined 0.25 (0.11, 0.42)

pooled proportions of BAM in

prospective studies using the

Rome III criteria for IBS-D was

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

25.0% (95% CI: 11.3–41.9).

Proportion (95% confidence interval)

Table 2 | Quality Assessment for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)-2 evaluation of each study included in the

meta-analysis assessing the prevalence of BAM in patients with IBS-D

Risk of bias Applicability concerns

Patient Index Reference Flow & Patient Index Reference

selection test standard timing selection test standard

Smith et al.23

Kurien et al.24

Gracie et al.21

Dhaliwal et al.22

Bajor et al.25

Aziz et al.26

either country in which the study was undertaken or the particularly with respect to clinical practice, diagnostic

particularly iteration of international guidelines that was criteria development and research.

used to make the diagnosis of IBS-D. These results have IBS is a common disorder worldwide, and whilst the

a number of important implications across the field, exact prevalence varies according to the wording of

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11 7

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S. A. Slattery et al.

questions used to define the disorder, it is most com- emphasis placed upon the attractiveness of making a

monly reported to be in the order of 5–10%.27 The relative positive diagnosis of IBS in primary care, without resort-

balance of diarrhoea vs. constipation varies considerably ing to investigations, by advisory bodies,39 the evidence

dependent on the geographical location, complicated by suggests otherwise. Hungin et al. demonstrated in a

the observation that patients can change from one subtype recent systematic review that primary care physicians

to another over time.6 The reported population prevalence tend to use additional testing to confirm the diagnosis,

of IBS-D is approximately 4%.2 Therefore, based on a UK arguably as a consequence of the current criteria not hav-

population of 64.1 million,28 it is possible to extrapolate ing the required sensitivity and specificity to ameliorate

that potentially 2.5 million individuals have IBS-D. A simi- concerns regarding diagnostic uncertainty.40 Given the

lar prevalence rate of IBS-D has been reported in a large sub-optimal characteristics of current symptom-based

longitudinal cohort study from the USA.29 By comparison, diagnostic criteria, various quantitative biomarkers have

2.3 million people live with coronary heart disease in the been investigated. Recently, Camilleri et al. reported that

UK.30 Although it is difficult to accurately estimate the total faecal bile acids, in conjunction with the measure-

community based population prevalence based upon data ment of colonic transit, were of utility in discriminating

derived from secondary/tertiary care centres, potentially in between health and the IBS state, as well as subtypes of

excess of 700 000 individuals in the UK have BAM, albeit IBS.41 In this study, faecal bile acids were elevated in

with symptoms consistent with, and/or a diagnosis of, IBS- patients with IBS-D, although 15.6% had undergone a

D. In reality, however, this figure may be further skewed, previous cholecystectomy and BAM was not screened for.

given that we excluded those with type 1/3 BAM and those Therefore, such biomarkers may be delineating the pres-

studies reporting patients with functional diarrhoea. None- ence of BAM rather than IBS per se considering that fae-

theless, it is entirely plausible that BAM is a prevalent, yet cal bile acids may be elevated in the former.42 Future

probably under-recognised, disorder in the general popula- guidelines could adopt an alternative stratagem where

tion. The question as to why BAM is under diagnosed patients with IBS-D like symptoms undergo a ‘test and

remains an enigmatic one and is almost certainly multifac- treat’ approach for BAM, analogous to that widely uti-

torial. For example, failure of BAM ab initio to enter the lised for dyspepsia.43 However, such an approach is likely

differential diagnosis,24 negative perceptions concerning to be limited by the cost and availability of SeHCAT test-

tolerability of traditional bile acid sequestrants and a pau- ing, as it is currently only available in 30–40% of GI cen-

city of guidance regarding optimal treatment regimens tres in the UK. A diagnostics consultation document

may play a pivotal role. A number of therapeutic options from the National Institute of Health and Care excellence

are available including cholestyramine, colesevalam, coles- concluded that presently there is insufficient evidence

tipol, aluminium hydroxide and obeticholic acid.31 Wilcox regarding the cost effectiveness of using SeHCAT in IBS-

et al. reported that cholestyramine and colestipol are D, although further research is warranted.44 Nevertheless

efficacious treatments, albeit limited by their tolerability the lack of availability of SeHCAT testing, particularly in

and hence bioavailability.32 While newer agents such as the USA, prompts the use of an empirical trial of bile

colesevalam and obeticholic acid having a promising role, acid sequestrants as a surrogate diagnostic measure. This

to date, there are no randomised controlled or comparison lack of availability of such testing should not discourage

trials establishing their efficacy in type 2 BAM. However, healthcare providers from the use of such a pragmatic

in a small double-blind placebo-controlled trial, coleseva- empirical trial of therapy, although this is often limited

lam has been shown to be efficacious in BAM related to by an individual’s tolerability of bile acid sequestrants.

Crohn’s disease.33 Nevertheless, significant knowledge gaps Our findings have important ramifications for (i) the

remain as to the long-term effectiveness and tolerability of interpretation of existing data and (ii) the design of

the current therapeutic armamentarium. future studies. With respect to the former, many studies

The clinical performance of internationally accepted have evaluated both pathophysiological and therapeutic

criteria including the Rome criteria, the most widely aspects of IBS-D. To date, the overwhelming majority of

accepted current standard for diagnosing functional gas- such studies have not actively sought to exclude BAM as

trointestinal (GI) disorders, remains limited.34, 35 For a differential diagnosis and therefore, the homogeneity of

instance, a diverse array of GI disorders such as coeliac study populations becomes limited. Therefore, such data

disease,36 inflammatory bowel disease37 and small bowel are skewed and thus the interpretation of the true effect

bacterial overgrowth38 may fulfil such criteria for the of the observation/therapeutic intervention becomes

diagnosis of IBS-D. While there has been particular more challenging to interpret, given this confounder.

8 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Systematic review with meta-analysis: bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D

Therefore, future studies could be markedly improved by criteria for IBS-D have BAM. Considering the marked

actively screening for BAM as part of the inclusion crite- socioeconomic burden of IBS-D, in conjunction with the

ria, thereby improving the homogeneity of participants. efficacy of bile acid sequestrants in treating BAM, such a

This study is not without significant limitations. There distinction has meaningful implications for contempora-

was significant heterogeneity seen in all of the analyses, neous clinical practice, future guideline development and

which was not explained by our subgroup analyses. On research.

account of the strict set of inclusion criteria, the number

of studies yielded from the literature search was relatively AUTHORSHIP

small and therefore did not permit formal assessment of Guarantor of the article: Dr Adam D Farmer, PhD

publication bias. Two of the studies identified applied the MRCP (UK).

Rome criteria retrospectively, which could potentially Author contributions: SAS: planned and conducted the

introduce a degree of ascertainment bias although Vanner systematic review and meta-analysis, wrote the manu-

and colleagues suggest that there is only a marginal dif- script. ON: revised the manuscript for important intellec-

ference in positive predicted value between retrospective tual content. ACF: supervised the study, conducted the

and prospective application of the Rome criteria.45 More- meta-analysis and revised the manuscript for important

over, all the studies reported herein are either from sec- intellectual content. QA: supervised the study, conducted

ondary or tertiary care centres and thus the applicability the meta-analysis and revised the manuscript for impor-

to community populations, as mentioned earlier, remains tant intellectual content. ADF: performed the methodo-

speculative. Similarly, other concerns regarding generalis- logical assessment and revised the manuscript for

ability focus on the fact that we chose to use <10% SeH- important intellectual content.

CAT retention at 7 days as our cut off for delineating All authors have approved the final version of the

BAM. We chose this particular cut off for two reasons. manuscript.

Firstly, in order to report a more conservative estimate of

prevalence rates in comparison to using <15% and sec- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ondly to provide a more clinically applicable result, as the The authors thank Dr Arasardnam, University Hospitals

probability of a positive therapeutic response to bile acid of Coventry and Warwickshire for clarification on the

sequestrants is negatively associated with retention inclusion criteria used his publication.

rates.46 We also chose to use SeHCAT testing as the ref- Declaration of personal interests: None.

erence standard for diagnosing BAM, although hitherto Declaration of funding interests: ADF is supported by the

the diagnostic accuracy of SeHCAT has only been evalu- Whitechapel Society of the Advancement of Gastroenter-

ated by response to treatment with bile acid sequestrants, ology, which had no input into the study design or man-

and therefore maybe liable to assessment bias due to lack uscript preparation.

of blinding both in investigators and patients.46 Further-

more, the lack of availability of SeHCAT testing outside SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Europe has limited the geographical spread from which Additional Supporting Information may be found in the

studies could have been undertaken. As a consequence, online version of this article:

the generalisability to other IBS-D populations around Figure S1. A Forest plot of the pooled proportions of

the world is purely conjectural, although there is little BAM in IBS-D patients in studies reported from the UK

objective evidence to suggest that prevalence rates of based studies.

BAM would be significantly different elsewhere. Figure S2. A Forest plot of the pooled proportions of

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that in excess BAM in IBS-D patient in studies using prospective data

of 1 in 4 patients meeting internationally accepted collection methods.

REFERENCES

1. Drossman DA. Rome III: The 2. Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence 3. Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. of and risk factors for irritable bowel article: the economic impact of the

3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gas- irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment

Associates, 2006. troenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 712–21. e4. Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 1023–34.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11 9

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S. A. Slattery et al.

4. Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American systematic reviews and meta-analyses of treatment. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;

gastroenterological association institute studies that evaluate healthcare 27: 653–9.

technical review on the pharmacological interventions: explanation and 32. Wilcox C, Turner J, Green J. Systematic

management of irritable bowel elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. review: the management of chronic

syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 18. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood diarrhoea due to bile acid

1149–72. e2. ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool malabsorption. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

5. Corsetti M, Van Oudenhove L, Tack J. for the quality assessment of diagnostic 2014; 39: 923–39.

The quest for biomarkers in IBS-where accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 33. Beigel F, Teich N, Howaldt S, et al.

should it lead us? Neurogastroenterol 155: 529–36. Colesevelam for the treatment of bile

Motil 2014; 26: 1669–76. 19. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis acid malabsorption-associated diarrhea

6. Canavan C, West J, Card T. The in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials in patients with Crohn’s disease: a

epidemiology of irritable bowel 1986; 7: 177–88. randomized, double-blind, placebo-

syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6: 20. Borenstein M. Introduction to Meta- controlled study. J Crohns Colitis 2014;

71–80. analysis. Oxford: Wiley, 2009. 8: 1471–9.

7. Ohman L, Tornblom H, Simren M. 21. Gracie DJ, Kane JS, Mumtaz S, 34. Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, Bolino

Crosstalk at the mucosal border: Scarsbrook AF, Chowdhury FU, Ford C, Pintos-Sanchez MI, Moayyedi P.

importance of the gut AC. Prevalence of, and predictors of, bile Validation of the Rome III criteria for

microenvironment in IBS. Nat Rev acid malabsorption in outpatients with the diagnosis of irritable bowel

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 36–49. chronic diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol syndrome in secondary care.

8. Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Motil 2012; 24: 983–e538. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 1262–70. e1

Prognosis in post-infective irritable 22. Dhaliwal A, Chambers S, Nwokolo C, 35. Dang J, Ardila-Hani A, Amichai MM,

bowel syndrome: a six year follow up et al. Bile acid diarrhoea. Gut 2013; 62 Chua K, Pimentel M. Systematic review

study. Gut 2002; 51: 410–3. (Suppl. 1): A122. of diagnostic criteria for IBS

9. Ghoshal UC, Ranjan P. Post-infectious 23. Smith MJ, Cherian P, Raju GS, Dawson demonstrates poor validity and utilization

irritable bowel syndrome: the past, the BF, Mahon S, Bardhan KD. Bile acid of Rome III. Neurogastroenterol Motil

present and the future. J Gastroenterol malabsorption in persistent diarrhoea. J 2012; 24: 853–e397.

Hepatol 2011; 26(Suppl. 3): 94–101. R Coll Physicians Lond 2000; 34: 448– 36. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP,

10. Wedlake L, A’Hern R, Russell D, 51. et al. Association of adult coeliac

Thomas K, Walters JR, Andreyev HJ. 24. Kurien M, Evans KE, Leeds JS, Hopper disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a

Systematic review: the prevalence of AD, Harris A, Sanders DS. Bile acid case-control study in patients fulfilling

idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as malabsorption: an under-investigated ROME II criteria referred to secondary

diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in differential diagnosis in patients care. Lancet 2001; 358: 1504–8.

patients with diarrhoea-predominant presenting with diarrhea predominant 37. Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of

irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment irritable bowel syndrome type symptoms meeting criteria for irritable

Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 707–17. symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel

11. Peters AM, Walters JR. Recycling rate 46: 818–22. disease: systematic review and meta-

of bile acids in the enterohepatic 25. Bajor A, Tornblom H, Rudling M, Ung analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:

recirculation as a major determinant of KA, Simren M. Increased colonic bile 1474–82.

whole body 75SeHCAT retention. Eur J acid exposure: a relevant factor for 38. Ford AC, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ,

Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013; 40: 1618– symptoms and treatment in IBS. Gut Moayyedi P. Small intestinal bacterial

21. 2015; 64: 84–92. overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome:

12. Roberts MS, Magnusson BM, 26. Aziz I, Mumtaz S, Boholah H, systematic review and meta-analysis.

Burczynski FJ, Weiss M. Enterohepatic Chowdhury FU, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7:

circulation: physiological, High Prevalence of Idiopathic Bile Acid 1279–86.

pharmacokinetic and clinical Diarrhea Among Patients With 39. National institute of health and care

implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002; Diarrhea-predominant Irritable Bowel excellence. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in

41: 751–90. Syndrome Based on Rome III Criteria. Adults. London: National Institute for

13. Camilleri M. Advances in Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; pii: Health and Care Excellence, 2008.

understanding of bile acid diarrhea. S1542-3565(15)00249-9. doi: 10.1016/ 40. Hungin AP, Molloy-Bland M, Claes R,

Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; j.cgh.2015.03.002. [Epub ahead of print]. et al. Systematic review: the

8: 49–61. 27. Spiller RC. Irritable bowel syndrome. Br perceptions, diagnosis and management

14. Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Shin A, Med Bull 2004; 72: 15–29. of irritable bowel syndrome in primary

Saenger A. Methods for diagnosis of 28. Key statistics for local authorities in care–a Rome Foundation working team

bile acid malabsorption in clinical England and Wales. report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;

practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 29. Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, 40: 1133–45.

2013; 11: 1232–9. Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley 41. Camilleri M, Shin A, Busciglio I, et al.

15. Williams AJ, Merrick MV, Eastwood NJ. Natural history of functional Validating biomarkers of treatable

MA. Idiopathic bile acid gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year mechanisms in irritable bowel

malabsorption–a review of clinical longitudinal population-based study. syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil

presentation, diagnosis, and response to Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 799–807. 2014; 26: 1677–85.

treatment. Gut 1991; 32: 1004–6. 30. Townsend N, Wickramasinghe K, 42. Pattni S, Walters JR. Recent advances in the

16. Ford AC. Applicability of the reported Bhatnagar P, et al. Coronary Heart understanding of bile acid malabsorption.

prevalence of bile salt malabsorption in Disease Statistics 2012 Edition. London: Br Med Bull 2009; 92: 79–93.

irritable bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther British Heart Foundation, 2012. 43. Aziz I, Kurien M, Sanders DS, Ford

2010; 31: 161–2; author reply 162-4. 31. Barkun AN, Love J, Gould M, Pluta H, AC. Screening for bile acid diarrhoea in

17. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. Steinhart H. Bile acid malabsorption in suspected irritable bowel syndrome. Gut

The PRISMA statement for reporting chronic diarrhea: pathophysiology and 2015; 64: 851.

10 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Systematic review with meta-analysis: bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D

44. Excellence National Institute of Health 45. Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, of bile acid malabsorption and

and Clinical Excellence. Diagnostics et al. Predictive value of the Rome measurement of bile acid pool loss: a

Consultation Document: SeHCAT criteria for diagnosing the irritable systematic review and cost-effectiveness

(tauroselcholic [75selenium] acid) for the bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol analysis. Health Technol Assess 2013;

Investigation of Diarrhoea Due to Bile 1999; 94: 2912–7. 17: 1–236.

Acid Malabsorption. London: National 46. Riemsma R, Al M, Corro Ramos I,

Institute of Health and Care Excellence, et al. SeHCAT [tauroselcholic

2012. (selenium-75) acid] for the investigation

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11 11

ª 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Origami Ball KusudamaDocument12 pagesOrigami Ball KusudamalstopmotionNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Tax On Partnerships Estates and TrustsDocument12 pagesTax On Partnerships Estates and TrustsLouina YnciertoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- DT 230 Manual PDFDocument102 pagesDT 230 Manual PDFCarlos ValenciaNo ratings yet

- ZED Partner Carriers: For 9W and S2 Employees Annexure A: List of Zed PartnersDocument4 pagesZED Partner Carriers: For 9W and S2 Employees Annexure A: List of Zed PartnersAakash SawaimoonNo ratings yet

- Aluminio BRONMETAL enDocument12 pagesAluminio BRONMETAL enPerica RakićNo ratings yet

- Preview of Tyre Retreading PDFDocument20 pagesPreview of Tyre Retreading PDFLucky TraderNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Industries List A PDFDocument62 pagesGujarat Industries List A PDFHydro TechNo ratings yet

- Automotive-Presentation-I.A.-AS1 20231013 193844 0000Document90 pagesAutomotive-Presentation-I.A.-AS1 20231013 193844 0000Renz Moyo ManzanillaNo ratings yet

- My10 Sram Tech Manual Rev ADocument97 pagesMy10 Sram Tech Manual Rev AUrip S. SetyadjiNo ratings yet

- ViewdocDocument12 pagesViewdocAnonymous P73cUg73LNo ratings yet

- Full Download Foundations of Education 11th Edition Ornstein Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Foundations of Education 11th Edition Ornstein Solutions Manualexonfleeting.r8cj3t100% (37)

- PFMS Transaction Details Sr. No. DDO Name Account No Ifsc Code Id Amount Scroll Status Beneficiary NameDocument18 pagesPFMS Transaction Details Sr. No. DDO Name Account No Ifsc Code Id Amount Scroll Status Beneficiary Nameajay kumarNo ratings yet

- Barton, Simko, 2002Document28 pagesBarton, Simko, 2002Lauren VailNo ratings yet

- Stefels Elementa 2018Document25 pagesStefels Elementa 2018Raghav PathakNo ratings yet

- Jokh2403055819330 5819330Document2 pagesJokh2403055819330 5819330Abhijeet TaliNo ratings yet

- Palm Jumeirah by GaneshDocument10 pagesPalm Jumeirah by GaneshJidhin VijayanNo ratings yet

- hw8 SolnsDocument9 pageshw8 SolnsJennyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Compartmentation: Cells and Tissues: Functional Compartments of The BodyDocument10 pagesChapter 3: Compartmentation: Cells and Tissues: Functional Compartments of The BodyShivani RailowalNo ratings yet

- CAT-1002 MR-2605 Five Zone Fire Alarm Control PanelDocument6 pagesCAT-1002 MR-2605 Five Zone Fire Alarm Control PanelAlex CristobalNo ratings yet

- Terms of Use: (End User License Aggrement)Document4 pagesTerms of Use: (End User License Aggrement)Imam MansyurNo ratings yet

- Business PlanDocument131 pagesBusiness PlanMikha BorcesNo ratings yet

- Is SPH8701Document3 pagesIs SPH8701dayshift5No ratings yet

- Pds Latest FormDocument4 pagesPds Latest FormMaria Fatima MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two, The Structure of Crystalline Solids PDFDocument23 pagesChapter Two, The Structure of Crystalline Solids PDFOmar Abu MahfouthNo ratings yet

- The Man With His Back Turned: by Agustín CadenaDocument2 pagesThe Man With His Back Turned: by Agustín CadenaSkrrt SkrrtNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet 1 - Ray Adrian LanduayDocument9 pagesActivity Sheet 1 - Ray Adrian Landuayralanduay29652No ratings yet

- Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013Document19 pagesAnti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013Atoy Liby OjeñarNo ratings yet

- Tib Amx AdministrationDocument384 pagesTib Amx AdministrationTaher HarrouchiNo ratings yet

- HulDocument39 pagesHulLakhan ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Mcs 021 Heat Emitter Guide For Domestic Heat Pumps Issue 21Document11 pagesMcs 021 Heat Emitter Guide For Domestic Heat Pumps Issue 21Denis DillaneNo ratings yet