Professional Documents

Culture Documents

G. Lebovits - Cracking The Code To Writing Legal Arguments

Uploaded by

Mel MattersOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

G. Lebovits - Cracking The Code To Writing Legal Arguments

Uploaded by

Mel MattersCopyright:

Available Formats

JULY/AUGUST 2010

VOL. 82 | NO. 6

Journal

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION

What Attorneys Can Also in this Issue

Election Law

and Cannot Say In and Insurance Law Update

Lawyering Then and Now

About Litigations

by Martin H. Samson

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1650923

THE LEGAL WRITER

BY GERALD LEBOVITS

Cracking the Code to

Writing Legal Arguments:

From IRAC to CRARC to

Combinations in Between

M

any legal-writing professors Lawyers who use IRAC or any of its counter-arguments at the application

teach their first-year law stu- variations will avoid missing impor- stage,6 the traditional IRAC model

dents the IRAC model as an tant, logical steps in an argument or overlooks these elements.

organizational method to write legal will fail to address the argument’s Lawyers may also use IRARC —

arguments. IRAC stands for Issue, weaknesses. All legal writers will another Legal Writer patent-pending

Rule, Application, and Conclusion. improve their writing skills and their format and a CRARC variant — when

Law students use it to pass exams, submitted product by using IRAC or drafting an objective memoran-

to outline, and to write the discus- one of its many variations.3 dum. IRARC stands for Issue, Rule,

sion sections of their legal memoran- The IRAC model has become so Application, Rebuttal and Refutation,

dums and the argument sections of pervasive in the legal community that Conclusion. The difference between

their briefs. Many students find that it has given rise to a seemingly endless CRARC and IRARC is that the former

IRAC gives their writing organization. array of other acronyms.4 Law pro- begins with a persuasive conclusion

Others find that IRAC prevents them fessors have created rich and varied statement and the latter begins with

from making creative arguments — terminology to describe legal writing a neutral issue statement. Because the

that it stifles them and impedes their and the legal-writing process.5 This Legal Writer recommends CRARC for

learning. They use it — when they use article is designed to introduce law- persuasive legal writing, this article

it — only because they are told to use yers to other organizational methods will focus on CRARC.

it, even though some professors — that go beyond IRAC. One method CRARC holds many advantages

notably legal-writing professors — opt is CRARC, the Legal Writer’s patent- over both IRAC and IRARC for per-

for a more flexible model.1 pending model. suasive briefs. Both IRAC and IRARC

After law school, some lawyers Of the many organizational models begin with a neutral restatement of

abandon their IRAC roots. Some of deviated from IRAC, one that fully cap- the issue in the case. When you restate

these lawyers become lazy: They tures all elements of persuasive legal an issue up-front, you miss an oppor-

write just to submit a document, with- writing is CRARC. CRARC stands for tunity to persuade the reader. CRARC

out devoting much effort to structur- Conclusion, Rule, Application, Rebuttal guides you to begin your argument

ing their legal analysis. Others find and Refutation, and Conclusion. You, with a conclusion, which allows you

IRAC too rigid: They find that it the lawyer, should use CRARC as a immediately to tell the reader why

prevents them from developing legal roadmap to structure an argument sec- you should win. It also helps you ana-

arguments according to their own tion when drafting a persuasive trial lyze important facts and prevents you

style of writing.2 These lawyers have or appellate brief. CRARC guides you from missing crucial facts. A properly

forgotten that law school taught them to begin an argument with a persua- CRARCed argument section address-

important and lasting skills. Their sive conclusion statement instead of a es the strongest arguments first, fol-

decision to draft briefs without using neutral issue statement. It also directs lowed by weaker arguments and

an organizational model is unwise. you to craft a rebuttal that acknowl- public-policy arguments. This is the

The audience for their persuasively edges the potential weaknesses of a cli- best method for persuasive writing.

written briefs — judges — need writ- ent’s case and preemptively refutes the It draws the court’s attention right

ing drafted according to an organiza- other side’s contentions. Anticipating away to the arguments with which it

tional method that conveys arguments a rebuttal will give you credibility might agree.

efficiently. without undercutting an argument. IRAC and IRARC should not be

Lawyers who refuse to use IRAC Although some IRAC models recog- ruled out completely; either tool can

should replace it with something else. nize the value of drafting an intro- help you draft neutral office memo-

Smart lawyers use IRAC variations ductory topic sentence in the form of randums. IRARC is better than IRAC

to formulate their written arguments. a conclusion or the need to address Continued on Page 50

64 | July/August 2010 | NYSBA Journal

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1650923

The Legal Writer

Continued from Page 64

Structuring the Brief 2. Sub-sub point heading

A valuable way to organize a legal Sub-sub thesis

because, like CRARC, it compels you argument is to give the reader a road-

to provide a rebuttal and refutation. map, which CRARC provides. A road- Point Heading

Just like the Rebuttal and Refutation map serves as a mini-thesis that tells Use CRARC for the thesis, sub-thesis,

section in CRARC, the rebuttal section the reader what you’re about to dis- and sub-sub thesis sections. The point

in IRARC will help you gain credibility cuss. Place your roadmap after your heading is the conclusion you want the

with the reader, and it will help you thesis and just before each individual reader to agree with, and it summarizes

focus your arguments. CRARC. A roadmap constructed under the basis for your conclusion. It should

Before we delve deeper into these the CRARC model instantly reveals be general enough to encompass all

models, here are some other IRAC the overall legal argument, the rule, sub-arguments. For more information,

variants that law professors recom- how the rule applies to a particular set see the Legal Writer’s column on writ-

mend and practitioners use: of facts, and the counter-argument, all ing effective point headings.24 The the-

• BaRAC. Bold assertion, Rule, before the reader begins to read the sis section shouldn’t be longer than

Application, and Conclusion.7 details of your argument. two pages. Organize your argument

• CIRAC. Conclusion, Issue, Rule, Place your Rebuttal and Refutation into as many sub-sections as you need,

Application, Conclusion.8 in the right place in your brief so as not depending on the number of issues. If

• CRAC. Conclusion, Rule, to undercut your argument. The places you have a two-part test, for example,

Application, Conclusion.9 with the most emphasis in an argu- use point heading I for the first part

• CRAFADC. Conclusion, Rule, ment are the beginning and the end, of the test and point heading II for the

Authority, Facts, Analogize/ while the place with the least emphasis second part of the test, if both parts

Distinguish, Conclusion.10 is the middle. With CRARC, an argu- of the test are at issue. The sub-point

• CREAC. Conclusion, Rule, ment begins and ends with a persua- headings will deal with the specific

Explanation of the law, sive conclusion. The best place for your prongs of the rule or elements of the

Application, Conclusion.11 Rebuttal and Refutation, then, is in the test. If you use sub-points, or sub-

• CRuPAC. Conclusion, Rule, middle of the argument. This section sub-points, then each one should also

Proof, Analysis, Conclusion.12 addresses the flaws in your argument be CRARCed. Having a thesis section

• FIRAC. Facts, Issue, Rule, and should be the least memorable. If after each sub-point and sub-sub point

Analysis, Conclusion.13 you follow CRARC, you’ll place the heading in a CRARC format might

• FORAC. Facts, Outcome, Rule, Rebuttal and Refutation section in the seem repetitive, but it will help readers

Application, Conclusion.14 middle of your argument, between understand your argument. Keep the

• IDAR. Issue, Doctrine, your application and final conclusion. sections concise. CRARC permeates

Application, and Result.15 This way, you show the reader that you every aspect of the brief. Its success

• IGPAC. Issue, General rule, understand your opponent’s position will depend on how you organize the

Precedent, Application, but you have good reasons to support arguments into points, sub-points, and

Conclusion.16 your own position. sub-sub points. The entire argument

• ILAC. Issue, Law, Application, The structure of a lawyer’s argu- section of the brief should be one large

Conclusion.17 ment section of a brief might look CRARC and, for the most part, each

• IRAAAPC. Issue, Rule, something like this: sub-point, sub-sub-point, and so on

Authority synthesis, Application, I. Point Heading

should be CRARCed.

Alternative analysis, Policy,

Conclusion.18 Thesis section CRARCing the CRARC

• IREAC. Issue, Rule, Explanation, A. Sub-point heading Use the CRARC model for each issue,

Application, Conclusion.19 and have the courage to limit the num-

Sub-thesis

• MIRAT. Material facts, Issues, ber of CRARCs to those issues that

Rules, Application, Tentative 1. Sub-sub point heading have a reasonable likelihood of success.

Conclusion.20 Sub-sub thesis Issues — and, thus, separate CRARCs

• RAFADC. Rule, Authority, — consist of individual grounds on

2. Sub-sub point heading

Facts, Analogize, Distinguish, which the court might grant the relief

Conclusion.21 Sub-sub thesis you seek if it agrees with you on that

• TREACC. Topic, Rule, B. Sub-point heading

issue but disagrees with you on every-

Explanation, Analysis, Counter- thing else.

arguments, Conclusion.22 Sub-thesis Your strongest CRARC, or at least

• TRRAC. Thesis, Rule, Rule expla- 1. Sub-sub point heading the one that will give you the greatest

nation, Application, Conclusion.23 relief, should be listed first, although

Sub-sub thesis

50 | July/August 2010 | NYSBA Journal

threshold arguments like those involv- • Paraphrase the law or quote • Case comparisons are ineffective,

ing the statute of limitations or juris- directly from the law. except when one case contains

diction always go first. Because you’ll • State your rules in order from facts similar to your case.

focus on proving your conclusion, those most favorable to your • In a thesis paragraph, provide

using CRARC will help you avoid case to those least favorable to only a brief application. You’ll

addressing tangential issues.25 your case under the law. Then apply the law to the facts in detail

cite your strongest authorities in later points and sub-points of

Beyond the Acronyms: first. the brief.

The Meaning of CRARC • Cite relevant statutes or case law

“C”: Conclusion. after each rule, but do not string- “R”: Rebuttal and Refutation.

• The Conclusion section is a suc- cite to show off your research. • Rebut your adversary’s strongest

cinct summary of your main • The Rule section can be more than arguments one at a time and

argument on an issue and why one paragraph; it should be as refute them, before moving on

you should win. long as it needs to be to encom- to the next rebuttal, with your

• This first “C” is a conclusion pass the rule. strongest counter-arguments.

about how the court should deal • Don’t give more rules than the • Bolster your credibility by show-

with your legal issue. court needs to decide your case. ing the court that you recognize

• The initial conclusion is your ini- Be brief and concise. counter-arguments (those that

tial and most valuable opportunity

to persuade the reader why you With CRARC, an argument begins

should win. This is what distin-

guishes CRARC from IRAC or and ends with a persuasive conclusion.

IRARC. With the latter two, unlike

with CRARC, you begin with a • Raise binding authority before criticize or distinguish the law

neutral restatement of an issue. you raise persuasive authority. or facts of a case you cited in the

• The Conclusion section shouldn’t • Consider using parenthetical Rule section). Explain why your

be a blanket restatement of your explanations to explain case law. position is correct despite poten-

point, sub-point, or sub-sub-point tial or apparent weaknesses.

heading. Restatements waste an “A”: Application. • Explain why your adversary’s

opportunity to persuade. The • Argue your facts here. arguments are unpersuasive.

Conclusion should succinctly • Apply to the facts of the case the Your first sentence in this section

summarize the argument you’ll rule you identified as relevant. If should begin with a statement

make in the CRARC ahead. It your rule has a set of elements or showing how (1) the opponent’s

could be more detailed than a factors, then apply them to your case is unpersuasive for a specific

heading, but it needn’t be. facts accordingly. reason, (2) your opponent’s use of

• In an appellate brief, the first • Even if the rule you’ve enunciated a case is misplaced for a specific

Conclusion answers the ques- comes from a case that contains reason, or (3) the opposing argu-

tion on appeal in your favor. In dissimilar facts, show how the ment isn’t compelling for a specif-

a trial memorandum, the first rationale behind the rule applies ic reason. After the first sentence

Conclusion will state why the in your case. in this section, state the law that

court should rule in your favor on • Don’t simply recite facts in shows the truth of the sentence.

the issue in your case. the Application section. The Then apply the law to the case.

Application section is where Then conclude. To rebut a second

“R”: Rule. law and fact meld. Attach legal or third argument, follow the

• The Rule section should consist of significance to the facts of your same framework.

a statement or series of statements case. Merely stating, without • State your opponent’s position

of the constitutional, statutory, applying, the facts of preceden- neutrally and honestly and then

or common-law authority you tial cases won’t persuade the refute that position with facts or

deem binding or persuasive in reader. Don’t expect the reader law favoring your position.

determining the legal issue. Raise to compare the cases with your • Don’t repeat rules you already

all relevant rules for the first time facts and reach the conclusions gave in your Rule section.

in the Rule section, not in the you urge.

Rebuttal and Refutation section. • Your Application contains your “C”: Conclusion.

• Whenever possible, limit yourself factual and legal arguments and • Your final conclusion should con-

to three or four rules. should support your conclusion. form to the first “C” section and

NYSBA Journal | July/August 2010 | 51

the point heading. But instead of Application: Gregory scratched he did not touch Lisa directly with a

arguing your issues, use the final Lisa’s leg with his umbrella. The part of his body, direct contact is unnec-

conclusion to state the relief you intent element is absent from this case. essary to establish battery. The indirect

seek. When Gregory scratched Lisa with his contact of his umbrella with Lisa’s leg

• This is the narrow conclusion: umbrella, he did not intend to touch satisfies the harmful contact element of

Tie the legal issue and your argu- Lisa harmfully or offensively. Gregory battery. The intent element, however, is

ments to the relief you seek. intended only to scare her. absent from this case. When Gregory

• The conclusion summarizes the Rebuttal and Refutation: Although scratched Lisa with his umbrella he

applicable sub-point or sub-sub- he did not touch Lisa directly with a did not intend to touch Lisa harmfully

point. part of his body, the indirect contact or offensively. He intended only to

Be specific about how the court of his umbrella with Lisa’s leg satisfies scare her. Therefore, the requisite ele-

should decide your case. In appellate the harmful contact element of bat- ment of intent is not met here.

Have the courage to limit the number of CRARCs to those issues

that have a reasonable likelihood of success.

briefs, also state whether the trial court tery. But although Gregory intended Conclusion: Because Gregory

or the intermediate appellate court to scare Lisa, merely intending to scare intended only to scare Lisa when his

made a correct or an incorrect deci- a person is not sufficient for battery, a umbrella scratched her leg, the court

sion — whether the appellate court specific-intent crime. To satisfy specific will probably find that Lisa has failed

should reverse or affirm the decision. intent, Lisa had the burden to estab- to prove that Gregory had specific

This shows your reader that every line lish that Gregory intended to harm intent to harm her. Therefore, the court

in between the first and last conclusion or offend Lisa when he scratched her will likely affirm the trial court’s deci-

of a CRARC proves your first conclu- with his umbrella. Because Lisa did not sion and find that Gregory is not liable

sion. prove that Gregory intended to harm for battery.

or offend her when he scratched her

Applying the CRARC Model: leg, the requisite element of intent for Compare

An Example of IRAC and CRARC battery is absent here. In the IRAC example, it was not appar-

Here’s one example of the CRARC Conclusion: Gregory did not intend ent until you got through the applica-

model for an argument section of a to harm or offend Lisa with his umbrel- tion what side the writer was advocat-

persuasive brief and one example of la. Thus, this Court should affirm the ing. Opening with an issue statement in

the IRAC model and a discussion sec- trial court’s decision and find that the form of a question gives the reader

tion for an objective memorandum Gregory is not liable for battery. the opportunity to follow the analy-

using the same issue and law. Notice sis from a neutral point of view. This

the difference in the persuasive power IRAC Example is why many recommend IRAC for

between these two models. Issue: The issue is whether Gregory is neutral legal memorandums. But the

liable for battery for scratching Lisa’s better option remains IRARC for objec-

CRARC Example leg with his umbrella even though he tive writing because, like the CRARC

Conclusion: Gregory is not liable to intended only to scare her. model, you’ll include a rebuttal and

Lisa for battery. He intended only to Rule: Battery is an intentional harm- refutation section in which you’ll take

scare Lisa when his umbrella scratched ful or offensive contact. [Add cite.] into account the weaknesses in the case

her leg. Battery requires a plaintiff to prove and any counter-arguments.

Rule: Battery is an intentional that the defendant developed the The CRARC model, in contrast, is

harmful or offensive contact. [Add specific intent to harm or offend the more persuasive than IRAC because it

cite.] Lisa must prove that Gregory plaintiff before or contemporaneously begins with a sharp conclusion state-

developed the specific intent to harm with the defendant’s contact with the ment as opposed to the neutral issue

or offend her before or contemporane- plaintiff. [Add cite.] Indirect contact by restatement in IRAC. From the begin-

ously with his contact with her. [Add a defendant, or contact with an instru- ning, the reader knows that you advo-

cite.] Only Gregory’s indirect contact mentality that makes contact with the cate Gregory’s position. The reader

or contact with an instrumentality plaintiff’s person, is sufficient to con- will view the rest of your argument

that makes contact with Lisa’s person stitute a battery. [Add cite.] through Gregory’s lens.

is sufficient to constitute a battery. Application: Gregory scratched The CRARC example is also more

[Add cite.] Lisa’s leg with his umbrella. Although persuasive than its IRAC counterpart.

52 | July/August 2010 | NYSBA Journal

CRARC provides a more credible anal- it is a tool built from research and lwionline.org/publications/seconddraft/nov95.

pdf (last visited June 7, 2010).

ysis of the law. In the battery example, experience, and one that provides the

14. Terrill Pollman, Building a Tower of Babel or

CRARC provides a rebuttal and refu- level of organization courts and judges Building a Discipline? Talking About Legal Writing, 85

tation of the intent issue that the need. ■ Marq. L. Rev. 887, 898 n.51 (2002).

IRAC model neglects. The rebuttal 15. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IRAC (last vis-

and refutation is an excellent tool ited June 7, 2010).

GERALD LEBOVITS is a judge of the New York

because it allows you to concede 16. Barbara Blumenfeld, Why IRAC Should Be

City Civil Court, Housing Part, in Manhattan IGPAC, Second Draft, Nov. 1995, at 3, available at

points that you must concede to win and an adjunct professor at Columbia University http://www.lwionline.org/publications/second-

on an issue, without undercutting School of Law and St. John’s Law School. He draft/nov95.pdf (last visited June 7, 2010).

your argument. It shows the reader thanks Alexandra Standish, his court attorney, 17. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IRAC (last vis-

that you understand your opponent’s and Nicholas Malone, his judicial intern from the ited June 7, 2010).

position but that you still have a per- University of Ottawa, for assisting in researching 18. Ellen Lewis Rice et al., IRAC, The Law Students’

suasive reason for the court to favor this column. Judge Lebovits’s e-mail address is Friend or Foe: An Informed Perspective, Second Draft,

Nov. 1995, at 13, available at http://www.lwionline.

your position under the law and the GLebovits@aol.com.

org/publications/seconddraft/ nov95.pdf (last vis-

given set of facts. ited June 7, 2010).

Like any other organizational meth- 19. Pollman & Stinson, supra note 5, at 261–62.

od, CRARC is only one way to write 1. See, e.g., Jessica E. Slavin, Did You Learn About

20. See John H. Wade, Meet MIRAT: Legal Reasoning

IRAC in Law School? How did IRAC Become Such an

a persuasive, logical, and consistent Important Part of Legal Writing Teaching? And Should

Fragmented into Learnable Chunks, 2 Legal Educ. Rev.

283(1990).

brief. Although critics argue that strict it Be?, Sept. 2008, http://law.marquette.edu/fac-

ultyblog/2008/09/11/did-you-learn-about-irac-in- 21. Jacobson, supra note 10, at 66–67.

adherence to any organizational meth-

law-school-how-did-irac-become-such-an-impor-

od hinders good writing,26 following 22. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IRAC (last vis-

tant-part-of-legal-writing-teaching-and-should-it-

be/ (last visited June 7, 2010). ited June 7, 2010).

CRARC helps you focus and develop

23. Kim Cauthorn, Keep on TRRACing, Second

strong and persuasive legal arguments. 2. Jane Kent Gionfriddo, Dangerous! Our Focus

Draft, Nov. 1995, at 4, available at http://www.

Should Be Analysis, Not Formulas Like IRAC, Second

With CRARC, each argument and each Draft, Nov. 1995, at 2, available at http://www. lwionline.org/publications/seconddraft/nov95.

paragraph within the argument will lwionline.org/publications/seconddraft/nov95. pdf (last visited June 7, 2010).

support your conclusion. CRARC pro- pdf (last visited June 7, 2010) (“Complex legal prob- 24. See Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Getting

lems simply don’t break down easily into a state- to the Point: Pointers About Point Headings, 82 N.Y. St.

vides a structure in which you can ment of a ‘rule’ and a statement of ‘legal reasoning’ B.J. 64 (Jan. 2010).

logically express your legal analysis. or ‘policy.’”).

25. See Andrew H. Baida, Writing a Better Brief: The

The heavy lifting of legal analysis still 3. James M. Boland, Legal Writing Programs and Civil Appeals Style Manual of the Office of the Maryland

remains your duty, but CRARCing will Professionalism: Legal Writing Professors Can Join the Attorney General, 3 J. App. Prac. & Process 685, 719

Academic Club, 18 St. Thomas L. Rev. 711, 731 (2006) (2001) (citing Stephen V. Armstrong & Timothy P.

consistently help you write persuasive (stressing that professors should teach organiza- Terrell, Thinking Like a Writer: A Lawyer’s Guide

briefs. tional models like IRAC). to Effective Writing and Editing 2-1(1992) (arguing

4. Id. at 730; see Anita Schnee, Logical Reasoning that organizational structure helps legal writers

develop legal arguments logically and persuasively,

Benefits to Using CRARC Over “Obviously,” 3 J. Legal Writing Inst. 105, 120–21

eliminating tangents)).

(1997) (discussing the deductive process of IRAC

IRAC or IRARC and similar models). 26. See, e.g., Jane Kent Gionfriddo, supra note 2, at 2.

Of the many variations of the IRAC 5. See generally Terrill Pollman & Judith M. Stinson,

model, CRARC — through its use IRLAFARC! Surveying the Language of Legal Writing,

56 Me. L. Rev. 239 (2004) (surveying legal-writing

of both an opening conclusion state- professors’ use and understanding of terminology).

ment and a rebuttal and refutation 6. See, e.g., Research, Writing & Advocacy 2006–

Pro Bono Opportunities Guide

section — stands as an effective model 07, The Paradigm for Predictive Legal Writing: www.nysba.org/volunteer

for persuasive written advocacy. In Using “IRAC,” available at http://www.law.msu.

form and substance, CRARC is a cru- edu/rwa/IRAC.pdf (last visited June 7, 2010). Looking to volunteer?

cial tool for lawyers seeking to argue 7. Pollman & Stinson, supra note 5, at 255. This easy-to-use guide will help you find

their clients’ cases in the appellate 8. Lisa Eichhorn, Writing the Legal Academy: A the right opportunity.

Dangerous Supplement, 40 Ariz. L. Rev. 105, 135–36 You can search by county, by subject area,

or trial context. It avoids a neutral (1998).

opening issue statement and forces and by population served.

9. Id. at 135.

the lawyer to acknowledge but also to 10. Sam M.H. Jacobson, Learning Styles and

Questions about pro bono service?

counter an adversary’s argument (sub- Lawyering: Using Learning Theory to Organize Thinking

and Writing, 2 J. Ass’n Legal Writing Directors 67–70

Visit the Pro Bono Dept. Web site

stance). CRARC also reflects an impor-

(2004). for more information.

tant strategy in its structure. It places

11. Christine M. Venter, Analyze This: Using www.nysba.org/probono

the conclusion statement up-front and Taxonomies To “Scaffold” Students’ Legal Thinking and (518) 487-5641

puts the rebuttal and refutation section Writing Skills, 57 Mercer L. Rev. 621, 624–26 (2006).

probono@nysba.org

in the middle of the argument (form). 12. Pollman & Stinson, supra note 5, at 259.

This does not reflect an arbitrary or 13. Sally Ann Perring, In Defense of [F]IRAC, Second

pointlessly rigid methodology. Rather, Draft, Nov. 1995, at 12, available at http://www.

NYSBA Journal | July/August 2010 | 53

You might also like

- How To Write An Appellate BriefDocument20 pagesHow To Write An Appellate Briefmoonrak100% (4)

- CREAC in The Real WorldDocument33 pagesCREAC in The Real WorldJuan Antonio Ureta GuerraNo ratings yet

- Civil ProcedureDocument764 pagesCivil ProcedureEA Morr100% (1)

- How To Write A Winning BriefDocument8 pagesHow To Write A Winning BriefDiane SternNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing G05 - 20 LegaleseDocument7 pagesLegal Writing G05 - 20 LegaleseMalagant Escudero100% (1)

- Write On A Guide To Getting On Law ReviewDocument33 pagesWrite On A Guide To Getting On Law ReviewWalter Perez NiñoNo ratings yet

- "Persuasive Legal Writing" by Daniel U. SmithDocument132 pages"Persuasive Legal Writing" by Daniel U. SmithDaniel U. Smith100% (17)

- Fundamentals of Legal WritingDocument38 pagesFundamentals of Legal WritingAlyssa Mari Reyes67% (3)

- Art of Legal WritingDocument28 pagesArt of Legal WritingammaiapparNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure & Litigation - A Practical Approach (Paralegal) PDFDocument764 pagesCivil Procedure & Litigation - A Practical Approach (Paralegal) PDFImén Kéchiche100% (5)

- How To Study LawDocument15 pagesHow To Study LawAnonymous vAVKlB1100% (3)

- Improve Your Legal Writing PDFDocument3 pagesImprove Your Legal Writing PDFJanette Sumagaysay100% (2)

- Legal Reasoning and Legal Writing 7th PDFDocument494 pagesLegal Reasoning and Legal Writing 7th PDFIrma Nosadse100% (24)

- Legal Persuasion TechniquesDocument47 pagesLegal Persuasion TechniquesNitish Verghese100% (1)

- Legal Writing-Journal of Legal Writing InstituteDocument384 pagesLegal Writing-Journal of Legal Writing Instituteaccuresult100% (4)

- Basic Legal Citation PDFDocument300 pagesBasic Legal Citation PDFCheryl West100% (1)

- 10 Tips For Better Legal WritingDocument12 pages10 Tips For Better Legal WritingYvzNo ratings yet

- One LDocument3 pagesOne LLawCrossing100% (1)

- The Principles of Pleading and Practice in Civil Actions in the High Court of JusticeFrom EverandThe Principles of Pleading and Practice in Civil Actions in the High Court of JusticeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Deep Issue GarnerDocument25 pagesDeep Issue GarnerJerome Morada100% (1)

- Persuasive Legal WritingDocument5 pagesPersuasive Legal Writingrevkimc406No ratings yet

- 5 Principle Legal WritingDocument10 pages5 Principle Legal WritingNitaino Ketaurie El100% (4)

- Week 1 Legal SkillsDocument13 pagesWeek 1 Legal SkillsAweSumNess83% (6)

- Law School HandbookDocument64 pagesLaw School HandbookUsama Ehsan100% (1)

- 34-2 Writing To Win Art and Science Compelling Written Advocacy - AuthcheckdamDocument44 pages34-2 Writing To Win Art and Science Compelling Written Advocacy - AuthcheckdamKat-Jean FisherNo ratings yet

- The Winning Brief - Tips 1-19Document3 pagesThe Winning Brief - Tips 1-19kayeNo ratings yet

- How To Write Edit and Review Persuasive Briefs - Seven Guidelines From One Judge and Two Lawyers PDFDocument13 pagesHow To Write Edit and Review Persuasive Briefs - Seven Guidelines From One Judge and Two Lawyers PDFLamberto Bonifacio Jr.No ratings yet

- List of NCCL BooksDocument14 pagesList of NCCL BooksEkateriné O' NianiNo ratings yet

- Quick Guide To Better Legal WritingDocument27 pagesQuick Guide To Better Legal WritingGlenda Montejo100% (1)

- Lecture-6 - Principles of Legal WritingDocument3 pagesLecture-6 - Principles of Legal WritinghhhhhhhuuuuuyyuyyyyyNo ratings yet

- I RacDocument18 pagesI Racdj weshmaticNo ratings yet

- Crafting A Law ResumeDocument18 pagesCrafting A Law Resumelyrkrish100% (1)

- Study Aid CatalogDocument19 pagesStudy Aid CatalogMuraru DanielNo ratings yet

- A Law Students Guide Legal Educations Knowledge, Skills, and Ethics Dimensions (Nelson P. Miller)Document287 pagesA Law Students Guide Legal Educations Knowledge, Skills, and Ethics Dimensions (Nelson P. Miller)Linda Khoza100% (1)

- Legal Reasoning and Legal Writing. Structure, Strategy, and Style PDFDocument542 pagesLegal Reasoning and Legal Writing. Structure, Strategy, and Style PDFAlaleh Irooni91% (11)

- Judicial Writing Manual: A Concise Guide for Clear Legal OpinionsDocument56 pagesJudicial Writing Manual: A Concise Guide for Clear Legal OpinionsKringNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide To Law School Cases:: How To Read Cases in & Summarize Them inDocument30 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To Law School Cases:: How To Read Cases in & Summarize Them inUnjul ZenNo ratings yet

- Understanding Judicial Decision-Making - The Importance of Constraints On Non-Rational Deliberations - Drobak, NorthDocument22 pagesUnderstanding Judicial Decision-Making - The Importance of Constraints On Non-Rational Deliberations - Drobak, NorthMegan HauNo ratings yet

- Psychology of PersuasionDocument21 pagesPsychology of PersuasionAhmet EbukNo ratings yet

- How To Research For MootDocument16 pagesHow To Research For MootSneha SinghNo ratings yet

- Coherence in Writing with Transition WordsDocument1 pageCoherence in Writing with Transition WordsNahin AminNo ratings yet

- How To Brief A Case - Lloyd Sealy Library at John Jay College of Criminal Justice PDFDocument5 pagesHow To Brief A Case - Lloyd Sealy Library at John Jay College of Criminal Justice PDFNurul Jannah100% (1)

- Legal ReasoningDocument4 pagesLegal ReasoningStacy Moses100% (1)

- The Empowered Paralegal - Cause of Action HandbookDocument13 pagesThe Empowered Paralegal - Cause of Action HandbookMichael Jones0% (1)

- 2010 Handbook On Discovery PracticeDocument124 pages2010 Handbook On Discovery PracticeFidel Edel ArochaNo ratings yet

- Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges, Reviewed by Jacob H. HuebertDocument6 pagesMaking Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges, Reviewed by Jacob H. Huebertjhhuebert5297100% (2)

- Discovery Practice HandbookDocument82 pagesDiscovery Practice Handbookwinstons2311No ratings yet

- Legal ResumeDocument1 pageLegal Resumetiffany_knapp8No ratings yet

- Basic Legal ResearchDocument373 pagesBasic Legal ResearchRobert Jimeno100% (4)

- The Basics of Legal WritingDocument2 pagesThe Basics of Legal WritingAlnerdz BuenoNo ratings yet

- Sharpening Your Legal Writing SkillsDocument2 pagesSharpening Your Legal Writing SkillsahmedNo ratings yet

- Good Legal Writing PDFDocument68 pagesGood Legal Writing PDFYan Lean Dollison100% (2)

- Client KeeperDocument46 pagesClient KeeperNicolette A. Tanksley100% (1)

- (Aspen Casebook) Stephen C. Yeazell, Schwartz - Civil Procedure-Wolters Kluwer (2015) PDFDocument606 pages(Aspen Casebook) Stephen C. Yeazell, Schwartz - Civil Procedure-Wolters Kluwer (2015) PDFjerry100% (1)

- Storytelling For LawyersDocument264 pagesStorytelling For LawyersShiv Mani NdrNo ratings yet

- CRAC MethodDocument7 pagesCRAC MethodSantiago Fajardo PeñaNo ratings yet

- Cracking the Code to Writing Legal ArgumentsDocument7 pagesCracking the Code to Writing Legal ArgumentsNica Cielo B. LibunaoNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Canadian Business LawDocument235 pagesFoundations of Canadian Business Lawkinginthenorth283No ratings yet

- ALE1 2022 Week 8 Office MemorandumDocument4 pagesALE1 2022 Week 8 Office MemorandumTâm MinhNo ratings yet

- Unit 14 Food Storage: StructureDocument13 pagesUnit 14 Food Storage: StructureRiddhi KatheNo ratings yet

- 03 Agriculture GeofileDocument4 pages03 Agriculture GeofilejillysillyNo ratings yet

- The Biology of Vascular Epiphytes Zotz 2016 PDFDocument292 pagesThe Biology of Vascular Epiphytes Zotz 2016 PDFEvaldo Pape100% (1)

- Effect of Grain Boundary Thermal Expansion on Silicon Nitride Fracture ToughnessDocument8 pagesEffect of Grain Boundary Thermal Expansion on Silicon Nitride Fracture Toughnessbrijesh kinkhabNo ratings yet

- AMS 2750 E Heat Treatment Standards ComplianceDocument3 pagesAMS 2750 E Heat Treatment Standards ComplianceQualidadeTFNo ratings yet

- ATPL theory summary formulas and guidelines (40 charactersDocument60 pagesATPL theory summary formulas and guidelines (40 charactersJonas Norvidas50% (2)

- Hexadecimal Numbers ExplainedDocument51 pagesHexadecimal Numbers Explainedmike simsonNo ratings yet

- Michigan English TestDocument22 pagesMichigan English TestLuisFelipeMartínezHerediaNo ratings yet

- Dead Reckoning and Estimated PositionsDocument20 pagesDead Reckoning and Estimated Positionscarteani100% (1)

- Daftar Obat Alkes Trolley EmergencyDocument10 pagesDaftar Obat Alkes Trolley EmergencyMaya AyuNo ratings yet

- A Review of Air Filter TestDocument14 pagesA Review of Air Filter Testhussain mominNo ratings yet

- Table of ContentsDocument2 pagesTable of ContentsPewter VulturelynxNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Pleiadian Emissaries of LightDocument3 pagesWho Are The Pleiadian Emissaries of LightMichelle88% (8)

- Helmut Lethen - Cool Conduct - The Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany (Weimar and Now - German Cultural Criticism) - University of California Press (2001) PDFDocument265 pagesHelmut Lethen - Cool Conduct - The Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany (Weimar and Now - German Cultural Criticism) - University of California Press (2001) PDFJaco CMNo ratings yet

- ASTM G 38 - 73 r95Document7 pagesASTM G 38 - 73 r95Samuel EduardoNo ratings yet

- GYROSCOPE ManualDocument8 pagesGYROSCOPE ManualAman BansalNo ratings yet

- Drewry Capability StatementDocument9 pagesDrewry Capability Statementmanis_sgsNo ratings yet

- Roke TsanDocument53 pagesRoke Tsanhittaf_05No ratings yet

- Section 5: Finite Volume Methods For The Navier Stokes EquationsDocument27 pagesSection 5: Finite Volume Methods For The Navier Stokes EquationsUmutcanNo ratings yet

- Touch-Tone Recognition: EE301 Final Project April 26, 2010 MHP 101Document20 pagesTouch-Tone Recognition: EE301 Final Project April 26, 2010 MHP 101Sheelaj BabuNo ratings yet

- Arizona State University DissertationsDocument5 pagesArizona State University Dissertationshoffklawokor1974100% (1)

- Haven, Quantum Social ScienceDocument306 pagesHaven, Quantum Social ScienceMichael H. HejaziNo ratings yet

- BS 0812-114 - 1989Document12 pagesBS 0812-114 - 1989عمر عمرNo ratings yet

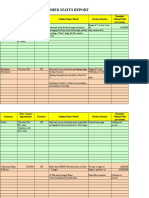

- Customer Status Update Report 27th January 2015 ColourDocument20 pagesCustomer Status Update Report 27th January 2015 ColourmaryNo ratings yet

- Max Brooks - The Zombie Survival Guide (Scanned Book)Document270 pagesMax Brooks - The Zombie Survival Guide (Scanned Book)tusko88% (8)

- Global Detection - Electronic and Electromechanical Sensors Catalogue 2006.10 PDFDocument800 pagesGlobal Detection - Electronic and Electromechanical Sensors Catalogue 2006.10 PDFSarah RichardNo ratings yet

- A Lesson Plan in English by Laurence MercadoDocument7 pagesA Lesson Plan in English by Laurence Mercadoapi-251199697No ratings yet

- Peter Linz An Introduction To Formal Languages and Automata Solution ManualDocument4 pagesPeter Linz An Introduction To Formal Languages and Automata Solution ManualEvelyn RM0% (2)

- Kitne PakistanDocument2 pagesKitne PakistanAnkurNo ratings yet

- RRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyDocument8 pagesRRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyAkash guptaNo ratings yet