Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Womens Fecundability and Factors Affecting It

Uploaded by

rssss44440 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views13 pagesRss

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRss

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views13 pagesWomens Fecundability and Factors Affecting It

Uploaded by

rssss4444Rss

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

Women

and

Health

Edited by

Marlene B. Goldman

Department of Epidemiology

Harvard School of Pubic Health

Boston, Massachusetts

Maureen C. Hatch

Department of Community and Preventive Medicine

Division of Epidemiology

(Mt. Sinai School of Medicine

New York, Neto York

ACADEMIC PRESS

‘Narco Snes an Teony Company

San Diego San Francisco New York Boston London Sydney Tokyo

11

Women’s Fecundability and Factors Affecting It

DONNA DAY BAIRD* AND BEVERLY I. STRASSMANN’

“Epidemiology Branch, National Insttte of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: "Department

‘of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

1. Introduction

‘World population fist exceeded a billion people in the early

1800s and it took approximately a century forthe next billion

increase, In 1999, our population exceeds six billion. Another

billion increase is projected in just over a decade [1]. The rapid

increase results from high feility populations where average

‘numbers of live binhs typically range from five 10 eight (2)

(Other pars ofthe world have undergone demographic transition

‘in association with industralization and hover at or below re-

placement reproduetive rates, The ansition from high tetlty

to low ferilty is influenced by complex socal changes thought

to be unrelated to basic biological capacity to reproduce

Reproduction i a relatively rae event for women in industs-

alized countries, Only 6.5% of US women of reproductive age

(15~44) gave birth in 1995 [3], and one out of six women aged

440-45 have never had a child [4]. Although most girls grow up

assuming that they will be able co have ehildren when and if

they choose to do 0, an estimated 10-15% of live births require

‘more than a year to conceive (5), suggesting that dese couples

say be experiencing some ferilty problems

“This chapter focuses on variability in biological capacity to r=

produce. How variable are different populations? What accounts

for variability among women within a population? Do women

with abundant food have greater capacity for reproduction?

‘Terminology tor deseribingferily and frilty problems is

not uniform across disciplines. We will follow Leridon (6) Fer

tilge refers 10 numberof live bins. a focus of demographic

research, Fecundity denotes the biological capacity to repro

‘duce. a focus of medical research. Fecundity is inherently dif

cult to measure: it cequres suecessul interaction of several

complex biological processes. Women may be fecund but choose

to contracept and not demonstrate fertility. Conversely. they ean

be fertile despite impaired fecundity by ulizing specialize in-

ferily teatments such asin vitro fertilization, Fecundabiliny

the probability of conceiving in a given time interval. prov

44 measurement tool for the study of fecundity. It usually is

measured as the probability of conceiving in any given men

sirual cyele (or month) among couples who are sexually wtive

and doing noting to prevent pregnancy. The probability of cn-

‘ceiving isa function of the Fecundity of the male and female

partners but also varies with frequency and timing of sexual

imereourse. As for any probability it cannot be assessed for an

individul couple but must be estimated for a group. If human

conceptions could be identified at time of fertilization. we could

measure total fecundabili: Instead, most data provide est-

mates of effective fecundablity (the probability of conceiy

pregnancy that survives to birth) or apparent fecundity (the

probability of having a clinically recognizable conception).

“This chapter explores the variability among coupes in their

ability to conceive, a measured by fecundabiliy. Unless spe-

cifically stated otherwise, fecundability will refer to apparent

fecundability, the probability of conceiving a efinically ecog-

nized pregnancy in any given menstrual cycle (or month). The

broader questions about social and economie deverminants of|

fertility and family size ae beyond ur scope. We start by sum-

rmarizing fecundability estimates ffom both eontracepiing and

‘oncontracepting populations. We then consider the major bio

logical processes required for successful pregnancy and begin

to quantify how failure of these processes contributes co reduc

ing fecundabilty, The largest section summarizes research on

factors affecting women’s Fecundabilty. Finally. we propose di

rections for furure research

Estimates of Fecundability

‘The majority of estimates of feoundabilty come from natural

fertility populations (populations in which contraception fs not

used to limit family size) Today, natural fete is most likely

to be found among rural populations of developing countries

land among conservative religious secis such as the utterites|

land Amish of North America [7.8]. There are possible theoreti

cal ag well as practial advantages to studying natural fertility

populations, Naural ferilty is thought to be the reproductive

patter of the vast majority of our evolutionary past. so natural

ferilty populations may be particularly suitable tor exploring

the evolved mechanisms tha underlie differences in female fe

cundability (9.10). Practically. the lack of contraceptive use can

simplify data collection, Waiting-time data for eafeulating fe

tcundabilty estimates can be conveniently collected for fist

birth intervals time from entry into a sexual union, e.g mar

riage, tothe dave of frst conception. imputed trom date of live

birth), When sexual union begins at marriage. existing mar

riage and birth records can be used to estimate fecundability

retrospectively.

‘Wood et als study ofthe Pennsylvania Amish provides one

‘ofthe best examples of first bith interval studies [11]. They used

the corefully-kept marviage and birth records of the Amish com=

munity to establish waiting times, Nearly all women martied be

fore age 30, soa fecundabilty estimate was calculated for women

aged 1829. The estimated effective fecundabilty fo the study

Sample of 271 women was 0.25 (the probability of becoming

pregnant in any given menstrual eycle was 25%, Similar methods

‘Were used in Taiwanese and Sri Lankan samples where effective

fecundability varied from 160 0.30 for 25-29 year ods [11]

Prior estimates of fecundabliy (based on clinically recognized

maceptions) in the first birth interval were summarized by

‘Wood (12), Populations were from the US, Taiwan. Peru. Brazil

copyright © 2300 by Antec Pes.

‘A is of tps aay form rsred

HAPTER 11, WOMEN'S FECUNDABILITY AND FACTORS AFFECTING IT 127

E wexico, France (including historical dat), Tunis, and Quebec.

eeundabilty estimates ranged from 0.14 to 0.31, with core

sponding conception waits of 10 months to 5.2 months

Enimates of fecundablity at the time of mariage often are

timited t0 young women and tend to be elevated by high coital

frequencies commonly seen with the onset of marriage (13,14).

Few stules have provided fecundability estimates for women

across the reproductive lifespan because they require accurate

information on the length of lactational amenorrhea, Studies in

contracepting populations require added information on birth

Control usage, These concerns can be addressed best with pro

Spective studies in which individual women are followed to

collect accurate wating-time dato

John et al. (15.16] conducted the fist prospective study of

fecundbility in «natural fertility population. the eural Bangla

Ges of Matlab Thana, Family plansing in this population was

minimal, Women were sought for interviews once a month

Nonetheless, absences ofthe women from home on’

view days resulted in gaps of 1wo to Four months in the records.

{A sample of 403 marred women aged 14-19 participated, Fe

‘eundabilty was 0.19 for nonbreastfeeding women and less

than 0.07 for breastfeeding women. However. even with the

prospectively-collected data, concern about accuracy of post

pertum amenorthes information led Leridon (J] «0 question

these fecundability estimates

‘Strassmann and Warmer [10] studied the waiting time 10 con-

ception in a Dogon village of 460 people in Mali. West Mica

The total ferility rate of the posteproductive women in this

village was 8.6 bins. and none of the women in any cohort

reported that they had ever used conteaception. During menses

Dogon women spend five nights sleeping at a menstrual hut,

which made.it possible co monitor female reproductive status

prospectively without inceviews. By censusing the women

present a the mensirul hus in the study village everynight for

‘wo years, Strassmann and Waener were able (0 prospectively

‘monitor the time From a woman's fist posipartum mensiuation|

to the onset of her last menstruation before a subsequent prea

ancy. Urinary steroid hormone profiles for 93 women in two

villages showed that, over 2 10 week period. women in the

principal study village went o the menstrual huts during

ofall menses and did aot go to the huts at other times {171

‘Thus, menstral hut visitation provided a reasonably reliable

indication of menstruation

The Dogon sample included SO women aged 15-31 with pro-

spectively observed conception waits. Fecundability was es

rated at 0.11 with covariates assigned mean values for the

population (covariates included age. time since marriage. gr

Vidity, and lactation), This fecundability estimate voresponds

to 3 conception wait of 8.3 months.

{a contracepting populations prospective stuies

roll women a the time they stop using contraception in order to

conceive provide the most accurate waiting-time data. Though

such studies have been dene. sone were done primarily :o mes

sure fecundability and none present fecundability estimates

based on statistical modeling ofthe entire distribution of walt-

ing cimes. However. first cyele conception rates provide a good

estimate of mean fecundability for a population (described in

Leridon (6), and these data have been published. We describe

three prospective studies that ceported these data.

‘Tietze [18] reported data on 611 US women who had their

TUDs removed in onder to become pregnant. Ages ranged from

17 w 42, with median age of about 25. The apparent fecunda-

bility (estimated by first cycle conception rates for clinically

recognized pregnancies) was 033. Mostof the women had been

pregnant before, so this estimate represents fecundabilty for

couples of proven Fertility. If women with no prior pregnancies

had been included, the estimate of mean fecundsbilty probably

would have bees lower

"The second stud, the North Carolina Early Pregnaney Study,

enrolled 221 volunters atthe time they begun trying to con-

czive [19]. Follow-up continued for six months or through the

eighth gestational week for those conceiving during the stay.

‘Women ranged in age from 21 to 42, with 80% between the ages

of 26 and 35: 35% were muligravid. The apparent fecundability

‘was 0.24 (estimated by frst cycle conception rates for clinically

recognized pregnancies), This is probably a low estimate be-

cause some women stopped contraception well into thei first

‘cle, so the opportunity o become pregnant during that frst

cycle wes reduced for these women. On the ather hand. women

‘with known fertility problems were excluded from participation,

50 we would expect this factor to bias the estimate upward.

‘The thd study (20), conducted in Denmark. enrolled 41

couples atthe time they began trying to conceive a first pre:

nancy. Couples were recruited from four trade unions: metal

workers. office workers, aurses, and dayeare workers. Most par

ticipants (925) were in their ewenties, Couples were followed

‘ntl elinically pregnant or through six menstrual cycles. which-

ever came fist, Fecundability as estimated by the first cycle

‘ronception rate For clinical pregnancies was 0.16

“The fecundability estimates presented here ae highly variable

(0.11 100.32), and variation exists both among the contacepting

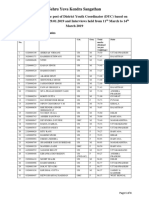

samples and among the natural fertility samples (Table 11.1),

Some ofthis variation may have methodologic explanations, In

natural ferility populations. accurate estimates

‘ainment of when a couple Begins having sexual i

wien lactational amenorrhea ends. Reportin

vary with study design as well as with educa

acteristics of participants.

I contracepting populations. waiting times can be messured

accurately in prospective sudies of women stopping contracep-

tion in order to conceive, but these studies are based solely on

women planning a pregnancy. This is a select group. Some

women never attempt #9 conceive because they do not want

childen. Other women become pregnant even though they are

rot intending #0. Inthe United States about half of pregnancies

fre unplanned (21). Thowgh nearly half of these unplanned

pregnancies were 19 women not using contraception the others

Were conceived during months when birt control had been

used, This latter group of women might be expected to have

high mean fecundabilty because they became pregnant while

using some form of birth control around the time they con-

ceived. Therefor. fecundabity estimates besed only on women

trying to conceive ae likly tobe lower than true fecundabiity

inthe population. Given the methodologic issues an the limited

fnumber of studies the degree to which populations differ in

their tru fecundabilty is nat known.

ecundabilty varies within populations as well. Regardless

‘of the mean fecundability for the population and whether iis a

sceuracy may

You might also like

- Tstransco Jao Annexure-IIDocument1 pageTstransco Jao Annexure-IIrssss4444No ratings yet

- Essay 2Document24 pagesEssay 2rssss4444No ratings yet

- Small Advertisement CWC 8x12 Eng - 080219Document4 pagesSmall Advertisement CWC 8x12 Eng - 080219rssss4444No ratings yet

- Tstransco Jao Annexure-IIDocument1 pageTstransco Jao Annexure-IIrssss4444No ratings yet

- Annexure III State Youth ParliamentDocument9 pagesAnnexure III State Youth Parliamentrssss4444No ratings yet

- CONFIDENCE - Joyce Meyer Ministries - Asia - HomeDocument32 pagesCONFIDENCE - Joyce Meyer Ministries - Asia - Homerssss4444No ratings yet

- Dyce NG Hand OutDocument6 pagesDyce NG Hand Outrssss4444No ratings yet

- Jesus Our Intercessor by Charles Capps PDFDocument123 pagesJesus Our Intercessor by Charles Capps PDFrssss4444100% (3)

- Result Dy C 11042019Document4 pagesResult Dy C 11042019Mks ViratNo ratings yet

- 235a8term Paper Guidelines 2013Document18 pages235a8term Paper Guidelines 2013rssss4444No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)