Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1987 Brundtland PDF

1987 Brundtland PDF

Uploaded by

Kurogane Taito0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views374 pagesOriginal Title

1987-brundtland.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views374 pages1987 Brundtland PDF

1987 Brundtland PDF

Uploaded by

Kurogane TaitoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 374

UNITED A

NATIONS

General Assembly bist

nr

GENERAL,

As42/427

4 Avgust 1987

ENGLISH

ORIGINAL: ARABIC/CHINESE/ENGLISH/

FRENCH/RUSSIAN/SPANISH

Forty-second session

Ttem 83 (e} of the provisional agenda’

DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION: ENVIRONMENT

port of the World Commission on Environment

~~ and Development

Note by the Secretary-General

1, The General Assembly, in its resolution 38/161 of 19 December 1983,

Ancer alia, welcomed the establishment of a special commission that should make

available a repor’. on environment and the global problématique to the year 2000 and

bevond, including vroposed strateaies tor sustainable development. The commission

Later adopted the name World Commission un Environment and Development. In the

Same resolution, the Assembly decided that, on matters witnin the mandate and

Durview of the United Nations Environment Programme, the report ot the special

COMMISSION sn>U1G In Che EACst instance be considered by the Governing Council of

the Programme, tor transmission to the Assembly together with its comments, and for

use as basic marerial in the preparation, tor adoption by the Assembly, of the

Environmental Ferspective to the Year 2000 and Beyond.

2. At ats fourteenth session, held ac Nairobi trom 8 to 19 June 1987, the

Governing Cuuneil of the United Natiuns Environment Prouramme adopted decision

14/14 of 16 June 1987, entitied "Report of the World Commission on Environment and

Development ard, inter alia, decaded to transmit the Commission's report to the

General Assembly together with a dratt resclution annexed to the decision for

consideration and adoption by the Assembly.

3. The report of the World Commicsion on Environment and Development, entitle

“Our Common Future", is hereby transmitted to the General Assembly. Decision 14/14

of the Governing Council, the proposed draft resolution and the comments of the

Governina Council on the report of the Commission can be found in the report of the

Governina Counesl on the work of 1ts fourteenth session. 1/

* ava2sis0.

87-18467 2499 CE)

a/42/427

enaiten

Paae 2

notes

1/ Offictar Records of the General Assembly, Forty-second sexsion, Supylemeny

No. 25 (A/42/25).

A/42/427

English

Page 3

ANNEX

Report of the World Commission on Environment

nd Development,

“out Common Future”

Members of the Commission

Chairman: Gro Harlem Brundtland (Norway)

Vice Chairman: Mansour Khalid (Sudan;

Susanna Agnelli (Italy)

Saleh A. Al-Athel (Saudi Arabia)

rnerd Chidzero (Zimbabwe)

Lamine Mohammed Fadika (C8te d'Ivoirs)

Volker Hauff (Federal Republic of Germany)

Istvan Lang (Hungary)

ma Shijun (People's Republic of China)

Margarita Marino de Botero (Colombia

Nagendra Singh (India)

Paulo Nogueira-Neto (Brazil)

Saburo Okita (Japan)

Shridath §. Ramphal (Guyana)

William 0. Ruckelshaus (USA)

Mohamed Sahnoun (Algeria)

Emil Salim (Indonesia)

Qukar Shaib (Nigeria)

Vladimir Sokolov (USSK)

Janez Stanovnik (Yugoslavia)

Maurice Strong (Canada)

Ex Officio

Jim MacNeill (Canada)

42/477

English

Page %

CONTENTS

Acronym List and Note on Terminology

From One Earth to One World: An Overview by the

World Commission on Environment and Development

Part I: Common Concerns

1 A Threatened Future

Symptoms and Causes

New Approaches to Environment and

Development

2 ‘Towards Sustainable Devolopment

The Concept of Sustainatle Develop

Equity and the Common Interest

Strategic Imperatives

Conclusion

3. The Role of the rnternational Economy

The Intecnational Economy, the Environment

and Development

Decline in the 19608

Enabling Sustainable Deve.opment

A Sustainable World Economy

Part Common Challenge:

4 Population and Human Rasonrcen

The Links with Environment and Develo:

The Population Perspective

A Policy Pramework

5 Pood Security: Sustaining the Potential

Achi ate

Signs of Crisis

The Challenge

Strategies for Sustainable Food Security

Food for the Future

araz/42d

Eng th

Pawn 6

6 Species and Ecosyste: jources for Development

The Proble Character and extent

Extinction Patterns and Trends

Some Causes of Extinction

Economic Values at Stake

New Approach: Anticipate and Prevent

International Action for National speci

Scope for National Action

The Need for Action

7 Energy: Choices for Environment and Development

Energy, Economy and ¥nvirvnment

Foseil Puele: The Continuing Dile:

Nuclear Energy: Unsolved Probl

Wood Fuels: The Vanishing Resource

Renewable Energy: The Untapped Potential

Energy Efficiency: Maintaining the Momentum

Energy Conservation Measures

Conclusion

8 Industry: Producing More with Lees

Industrial Growth and its impact

Sustainable Industrial Development in a

Context

Strategies for Sustainable Industrial

Development

9 ‘The Uroan Challenge

The Growth of Citi.

The Urban Challenge in Developing Countries

International Cooperation

Pact III: Common Endeavours

10. Managing the Commons

The Balance of Life

A Key (o Sustainable Development

Antarctica: Towarde Global Cooperation

curity, Development, and the Environwent

11 Peace

Environmental Stress as a Source of Conflict

Conflict as a Cause of Unsustainable Development

Towards Security and Justainable Development

4/42/427

English

Page 7

12 Towards Common Action: Proposals for Institutional

and Legal Change

The Challenge for Institutional and Legal Change

Proposals for Institutional and Legal Charge

A Call for Action

Annexe 1 Summary of Proposed Legal Principles for Environmental

Protection and Sustainable Development

Annexe 2 The Commission and Its Work

Throughout thie report, quotes from some of the many people who

spoke at WCED public hearings appear in boxes to illustrate the

range of opinions the Commission was exposed to during its thr

years of work. Thay do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Aeaarhet

Engl ists

Page

ars,

CCAMLR

CIDIE

CMEA

DIESA

ECB

eLc

FAG

GATT

cpp

Gems

GESAMP

np

GRID

IAEA

1cRP

tesu

(DA

TGBP

LIASA

ACRONYM LIST AND NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

Antare' ic Treaty Syatem

Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine

Living Resources

Committee of International Development Institutions

on the Environment

Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

United Nations Department for International Economic

and Social attairs

United Nations Environment Coordination Board

Economic Commission Cor Bucope

Bucopean Economic Community

Exclusive Economic Zones

Environment Liaison ¢ atre

Pond and Agricntture Organization of the United

Nations

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

gross domestic p oduct

Global Environment Monitoring system

Group of Experts on Scientific Aspect of Marine

Pollution

gross national produc

Global Resource Information Databage

International Atomic Enecgy Agency

International Commission on Radiological Protection

Inteenational Council of Scientific Unions

International Development Association

International Geosphere Biosphere Project (of ICSU)

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

LIED

ILO

IMF

Loc

Tu

rucn

IWC

Loc

NASA

NCS

NGO

NICs

Nuss

oEcD

ODA

PPP

‘TNCB

UNCHS,

UNCTAD

UNDA

UNDRO

UNEP

UNESCO

UNTDO

n/aza27

English

Page 4

International Institute for Environment and

Development

International Labour Organization

International Monetary Fund

Intergovercnmental oc:

nographic Commission

Intecnational Telecommunications Union

Intecnational Union for the Conservation of Nature

and Natural Resources

International Whaling Commission

London Dumping Convention

manufacturing value added

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Conservation Strategies

non-governmental organizations

newly industrialized countries

Nuclear Safety Standacde

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Official Development Assistance

Poliuter Pays Principle

transnational corporations

United Nations Centce for Human settle:

nts (HABITAT)

United Nations Conference o1 Trade and Development

United Nations Disarmament Association

Office of the United Nations Disaster Reliot

Co-ordinator

United Nations Environment Programme

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural

Organization

United Nations Industrial Development organization

Aa as

Hawg List

Page 10)

wao World Health organization

wao World Meteorological Organ.zation

WRI World Reaources Institute

wwe World Wildlife Fund

The grouping of countries in the presentation of data is

indicated in the appropciate places. Tne tera ‘industrial

countries’ generally encompasses the UN catcgories of developed

Macket economies and the socialist countries of Eautern Europe

and the USSR. Unlase ctherwise indicated, the term ‘doveloping

country! refers to the UN grouping of developing-countcy market

economies and the socialist countries of Avia. The tecm ‘Third

World’, unless the context implies otharwiae, generally cetera

to the developing-country marke: economies as defined by the UN

uni indicated otherwise, tone are metric (1,000 kilogra

or 2.204.6 pounda). Dollara are cucrant 0S dollare of US

dollars for the year apecicied.

Asa2/427

Engtists

Page 11

CHAIRMAN'S FOREWORD

"A global agenda tor change" - this was what th

World Commission on Environment and Development was asked

to formulate. It was am uryent cal by the General

Aswembly of the United Nations:

to propose long-term environmental strategies

for achieving suctainable development by the

year 2000 and beyond;

to recommend ways concern for the environment

may be translated into greater co-operation

among deveioping countries and between coun rie:

at different stages of economical and social

development and lead to the achievement of

common and mutually supportive objectives that

take account of the interrelationships between

people, resources, environment, and development;

to consider ways and means by which the

international community can deal more

eff, tively with environment concerns; and

to help detine shared perceptions of long-term

environmental issues and the appropriate efforts

needed to deal successfully with the probleme of

Protecting and enhancing the environment, a

long-term agenda for action during the coming

decades, and aspirational goals for the world

community.

When I was called upon by the Secretary-General of

the Inited Nations in December 1983 to establish and chair

2 special, indepeudent conmission to address this major

challenge to the worlu community, 1 was acutely aware that

this was no small task and obligation, nd that my

vay to day responsibilities as Party leader made it seem

Plainly prohibitive. What the General Assembly asked for

also seemed to be unrealistic and much too ambitious. At

the same time, it was a clear demonstration of the

Widespread feeling of frustration and inadequacy in the

intern:'” ual community about our own ability to address

the vitw ‘Tobal issues and deal effectively with them

That tect is a compelling reality, and should not

vacily be diomisced. Since the answers to fundamental and

serious concerns are not at hand, there is no alternative

but to keep on trying to find them.

n/a2/427

feng Fit

page 12

All this was on my mind when the Secretary General

Presented me with an argument to which there waa no

convincing rebuttal: No other political leader had become

Prime Minister with a background of several years of

political struggle, nationally and internationally, as an

environment minister. Thia gave some hope that the

environment was not destined to remain a side issue in

central. political decision making

In the final analysis, 1 decided to accept the

challenge. The challenge of facing the future, and of

safeguarding the interests of coming generations. For it

was abundantly clear: We needed a mandate for change

We live in an era in the Nistory of nations when

there is gteater need than ever for co-ordinated political

action and responsipility. ‘The United Nations and its

Secretary-General are faced with an enormous task and

burden. Responsibly meeting humanity's gual and

aspirations will require the active support of us all.

My reflections and perspective were also based on

other important parte of my own political experience: the

preceding work of the Brandt Commission on North. South

issues, and the Palme Commission on security and

disarmament issues, on which I served.

I was being asked to help formulate a third and

compelling call for political action: After Brandt's

rogramme for Survival and Common Crisis, and after

Palme's Common Security, would come Common Puture.

This was my message when Vice Chairman Mansour Khalid and

I started work on the ambitious task set up by the United

Nations. This report, as presented to the UN General

Assembly in 1987, is the result of that process.

Perhaps our most urgent task today ia to persuade

fations of the need to return to multilateraliem. The

challenge of reconstruction after the Second World War was

tne real motivating power benind the establishment of our

post-war international econowtic system. The challenge of

finding sustainable development patns ougnt to provide tne

impetus - indeed the imperative - for a renewed seatch for

multilateral solutions and a restructured invernational

economic system of co-operation. These challenges cut

across the divides of national sovereignty, of linited

strategies for economic gain. and of separated disciplines

of science

4/42/4627

Fog ist

Page 14

After a decade and a half of a standstill or even

deterioration in global co operation, I believe the time

has come for highe. expectations, for common goals puraued

together, for an increased political will to addroee our

common future

There was a time of optimism and progr

1960s. when there was Greater hope for a braver n

and £0: prograsaive international id Colont

with natuzal cesources were becoming nations. The ideals

of co-operation and sharing seemed to be seriously

pursued. Paradoxically, the 1970s s1i4 slowly into moods

of reaction and isolation while at the same time a seri

of UN conferences offered hope for greater co-operation on

rajor 18 The 1972 UN Conference on the Human

Environment brought the industrialized and developing

Nations together to delineate the “rights” of the human

family to a healthy and productive environment. A string

of such meetings followed: on the rights of people tv

adequate food, to sound housing, to safe water, to access

to means of choowing the size of their families.

The present decade hae been marked by a retreat from

social concerns. Scientists bring to our attention urgent

but complex problems bearing on our very survival: a

warming globe, threats to the Earth's ozone layer,

consuming agricultural land. We respond by demanding more

details, am by assigning the problems to institutions ill

equipped to cope with them. Environwentai degradation,

first seen as mainly a problem of the rich nations and a

side effect of industrial wealth, has become a survival

issue for developing nations. It is part of the downward

spiral of linked ecological and economic decline in which

many oi the poorest nations are trapped. Despite official

hope expressed on all sides, no trends identifiable today,

no progtammes or policies, offer any real hope of

narrowing the growing gap between rich and poor nations.

And ae pact of ouc “development”, we have amasued weapons

arsenals capable of diverting the paths that evolution nas

followed for millions of years and of creating a planet

our ancestors would not recognize.

When the terms of reference of our Commission were

originally being diecuesed in 1987, there were those who

wanted its considerations to be limited to “environmental

issues" only. This would have been a grave mistake. The

environment does not exist as a sphere separate from human

actions, ambitions, and needs, and attempts to defend it

in isolation from human concerns have given the very word

“environment” a connotation of naivety in some political

circles. The word “development” has also been narrowed by

sone into a very limited focus, along the lines of "what

poor nations should do to become richer", and thus again

ie automatically dismissed by many in the international

arena au being a concern ot specialists, of those involved

in questions of “development assistance”

442/427

Ena tint,

Pane 1a

But thi all live; and

"development" is what we all do in attempting to improve

our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable.

Further, development issues must be seen as crucial by the

pol'tical leaders who feel that their countries have

reacned a plateau towards which other nations must

strive. Many of the developmen: paths of the

industrialized nations are clearly unsustainable. And the

development decisions of these countries, because ot their

great economic and political power, will h profound

effect upon the ability of all peoples to sustain human

progress for generations to cone.

Many critical survival issues are related to uneven

development, poverty, and population growth. They all

place unprecedented pressures on the planet's lands,

watere, foresta, and other natural resources, not leaet in

the developing countries. The downward spiral of poverty

and environmental degradation {a a waste of opportunities

and of resources. In particular, it is a waste of human

resources. These links between poverty, inequality. and

environmental degradation formed a major theme in our

analysis and cecommendations. What is needed now is a new

eca of economic growth growth that is forceiul and at

the same time socially and environmentally sustainable.

Due to the scope of our work, and to the need to

have a wide perspective, I was very much aware of tne need

to put together a highly qualified and influential

political and scientific team, to constitute a truly

independent Commission. This was an essential part of a

successful process. Together, we should span the globe,

and pull together to formulate an intecdisciplinary,

integrated approach to global concerns and our common

future. We needed broad participation and a clear

majority of members from developing countries, to reflect

world realities. We needed people with wide experience,

and from all political fields. not only from environment

or development as political disciplines, but from all

areas of vital decision making that influence economic and

social progress, nationally and internationally.

We therefore come from widely differing backgrounds:

foreign ministers, finance and planning officials,

policymakers in agriculture, science, and technology

Many of the Commigsioners are cabinet ministers and senior

economists in their own nations, concerned largely with

the affairs of those countries. As Commissioners,

however, we were acting not in our national roles but as

individuals; and as we worked, nationaliam and the

artiticial divides between "industrialized" and

"developing", between East and West, receded. In their

place emerged 4 comaun concern Cor the planet and the

interlocked ecological and economic threats with which its

people, institutions, and governments now grapple.

/

ayansar7

Englian

Pane 15

During the time we met as a Commission, tragedi

such as the African famines, the leak at the pesticide:

factory at Bhopal, India, and the nuclear disaster at

Chernobyl, USSR appeared to justify the grave predictions

about the human future that were becoming commonplace

during the mid-1960s. But at public hearings we held on

five continents. we also heard from the individual victine

of more chronic, widespread disasters: the debt crisis,

stagnating aid to and investment in developing countries.

falling commodity prices and falling personal incom we

became convinced that major changes were needed. both in

attitudes and in the way our societies are organized.

The question of population - of population pr.

of population and human rights - and the links between

these celated issues and poverty, environment, and

development proved to be one of the more difficult

concerns with which we had to struggle. The differences

of perspective seemed at the outset to be unbridgeable

and they required a lot of thought and willingnose to

communicate across the divides of cultures, religions, and

regione

ure

Another auch concern waa the whole area of

international economic relations. [n these and in a

number of other important aspects of our analysis and

recommendations, we were able to develop broad agreement.

The fact that we all became wiser. learnt to look

across cultural and historical barriers, was essential.

There were moments of deep concern and potential crisis

moments of gratitude and achievement, moments of success

tn butlding a common analysis and perspective. The result

is clearly more global, more realistic, more

forward looking than any one of us alone could nave

created. We joined the Commission with different views

and perspectives, different values and beliefs, and very

different experiences and insights. After these three

yeare of working together, travelling, listening, and

discussing, we present a unanimous report

1 am deeply grateful to all the Commissioners for

their dedication, their foresight and peraonal commitment

to our common endeavour. It has been a truly wonderful

team. The spirit of triendship and open communication.

the meeting of minds and the process of learning and

sharing, have provided an experience of optimisn,

something of great value to all cf us, and. I believe, to

the report and its message. We hope to share with others

our learning process, and all that we have experienced

together. It is something that many others will have co

experience if global sustainable development is to be

achieved.

The Commission has taken guidance from people in ail

walks of life. It is to these people to all the peoples

of the world that the Commission now addresses itself

a/an/a2?

na Tish

page 16

In 80 doing we speak to people directly as well as to the

institutions that they have established.

The Commission ia addressing governments, directly

and through their various agencies and ministries. The

congregation of governments, gathered in the General

Assembly of the United Nations, will be tne main

recipients of this report.

The Commission is also addressing private

enterprise, from the one-person business to the great

multinational company with a total economic turnover

greater than tha’. of many nations, and with possibilities

for bringing about far-reaching changes and improvements

But first and foremost our message is directed

towards people. whose well-being is the ultimate goal of

all environment and development policies. In particular,

the Commission is addressing the young. The world's

teachers will have a crucial role to play in bringing this

report to them.

If we do not succeed in putting our message of

urgency through to today's parents and decision makers, we

rigk undermining our children's fundamental right to a

wealthy, lite-enhancing environment. Unless we are able

to translate our words into a language that can reach the

minds and hearts of people young old, we shall not be

able to undertake the extensive social changes needed to

correct the course of development.

‘The Commission has completed ite work. We call for

a common endeavour and for new norms of behaviour at all

levels and in the interests of all. The changes in

attitudes, in social values, and in aspirations that the

report urges will depend on vaat campaigna of education,

debate and public participation.

To thie end, we appeal to "citizens" groups, to

non-governmental organizations, to educational

institutions, and to the scientific community. They have

all played indispensable roles in the creation of publi

awareness and political change in (he past. They will

play a crucial part in putting the world onto sustainable

development paths, in laying the groundwork for Our Common

Future

The process that produced this unanimous report

proves tnat 1t 16 possible to join forces, to identity

common goals, and to agree on common action. Each one of

the Commiswioners would have chosen different words if

writing the report alone. Still, we managed to agree on

the analysis, the broad remedies, and the recommendations

for a sustainable course of development

4/42/427

English

Paye 17

In the final analysis, this is what it amounts to:

furthering the common understanding and common spirit of

responsibility go clearly needed in a divided world.

Thousands of people all over the world have

contributed to the work of the Commission, by intellectual

maans, by financial means, and by sharing their

experiences with us through articulating their neede and

demands. 1 am sincerely grateful to everyone who has made

guch contributions. Many of their names are found in

Annexe 2 of the report. My particular gratitude goes to

Vice Chairman Mansour Khalid, to all the other members of

the Commission, and to Secretary General Jim MacNeill and

hie staff at our secretariat, who went above and beyond

the call of duty to assist us. Their enthusiasm and

dedication knew no limits. I want to thank the chairmen

and members of the Intergovernemental Inte: atonal

Preparatory Committee, who co-operated closely with the

Commission and provided inwpication and support. 1 thank

also the Executive Director of the United Nations

Environment Programme, Dr. Mostafa Tolza, for his

valuable, continuous support and interest.

Gro Harlem Brundtland

Oslc, 20 March 1987

A/42/427

English

vage 18

FROM ONE ZARTH TO ONE WORLD

An Ovecviow by the

World Commigeion on Environment and Development

1. In the middle of the 20th century, we saw our planet from

Space for the firwt time. Historians may eventually find that

this vision had a greater impzct on thought than did the

Copernican revolution of the 16th century, which upset the human

self-image by revealing that the Earth is not the centre of the

univer From space, we see 2 small and fragile ball dominated

not by human activity and edifice but by a pattern of cloud

oceans, greenery, and soils. Humanity's inability to fit its

activities into that pattern is changing planetary systems

ntally. Many such changes are accompanied by

tening hazards. Tuis new reality, from which there is

must be recognized - and managed.

2. Fortunately, this new reality coincides witn muie positive

nts new to this century. We can mova information and

ter around the globs thai before; we can produce

more food and more goods with less investment of resources: our

technology and science gives us at least the potential to look

deeper into and better understand natural systems. From space

we can and study the Zacth 0 organism whose health

depends on the health of a1 its parts. We have the power to

reconcile human affaires with nstural lawe and to thrive in the

Process. In this our cultural and spiritual heritages can

reinforce our economic interests end curvival imperative

3 This Commiasion balievea that people can build a future

that is more prosperous, more just, and more secure. Our report

Qur Common Future. is not a prediction of ever increasing

environmental decay, poverty, and hardship in an ever more

polluted world among ever decreasing resources. We see instead

the possibility for a new era of economic growth, one that must

be based on policies that stetain and expand the env‘ronmenta

resource base. And we believe such growth to be absolutely

essential to relieve the grest poverty that is deepening in much

of the developing world.

4. But the Commission's hope for the future is conditional on

decisive political action now tc begin managing environmenta

resources to ensure both sustainable humat. progress and numan

survival. We are not forecacting a future; we are serving a

notice - an urgent notice based on the latest and best eclentiric

evidence - that the time has cone to take the decisions neaded to

secure the resources to sustain this and coming generavions. we

do not offer a detailed blueprint for action, but instead a

pathway by which the peoples of the world may enlarge their

spheres of cooperation.

4/42/4277

English

Page 19

1, THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE

1. Successes and

S. Those looking for success and signs of hope can find

See eae tna uoridie adaita eho eon cena! and aciy

the proportion of the world's adults who can read and writ

climbing; the proportion of children starting echool is rising:

and global food production increases faster than the population

grows.

6. But the same proc: that have produced these gaing have

given rise to trends that the plinet and its people cannot long

bear. These have traditionally been divided into failures of

‘development’ and failures in the management of our humau

environment. On the development side, in terms of absolute

numbers there are more hungry people in the world than ever

Vefore. and their numbers are increasing. So are the numbers who

cannot read or write, the numbers without safe water or safe and

sound homes. and the numbers short of woodfuel with which to cook

and warm themselves. The gap between rich and poor nations 16

widening - not shrinking - and there is little pro: pect, given

Present trends and institutional arrangements, that this proc

will be reversed.

7. There are also environmental trends that threaten to

radically alter the planet, that threaten the lives of many

species upon it, including tne human species. Eacn year anotner

6 million hectares of productive dryland turns into worthl:

Sesert. Over three decades, this would amount to an area roughly

as large as Saudi Arabia. More than:11 million hectares of

forests are destroyed yearly, and this, over three decades, would

equal an area about the size of Indi

converted to low-gr.

Much of this forest is

farmland unable to support the farmers who

settle it, In Europe, acid precipitation kills forests and

lakes and damages the artistic and architectural heritage of

nationa: it mey have acidified vant tracts of soil beyond

reasonable hope of repair. The burning of fossil fuels puts into

the atmosphere carbon dioxide, which is causing gradual global

warming. This ‘greenhouse effect’ may by early next century have

increased average global temperatures enough to shift

agcicultucal production areas, raise sea levels to flood coastal

cities, and disrupt national economi Other industrial gases

threaten to deplete the planet's protective ozone shield to such

an extent that the number of human and animal cancers would rise

sharply and the oceans’ food chain would be disrupted. Industry

and agriculture put toxic substances into the human food chain

and into underground water tables beyond reach of cleansing.

8 There has been a growing realization in national

Governments and multilateral institutions that it is impogsibl

to separate economic development issues from environment issues:

many forms of development erode the environmental resources upon

whicn they must be based, and environmental degradation can

undermine economic development. Poverty is a major cause and

effect of global environmental probl It is therefore futile

to attempt to deal with environmental problems without a broader

A awaer

Rog taste

aye 20

perspective that encompasses the factors underlying world poverty

and international inequality.

9. Thewe concerns were behind the establishment in 1983 of the

worid Commission on environment and Development by the UN General

Assembly. The Coamission is an independent body, linked to but

outside the control of yovernments and the UN system. The

Commission's mandate gave it three objectives: to re-examine the

critical environment and development issues and to formulate

realistic proposals for dealing with them; to propose new forms

of international cooperation on these igsues that will influence

policies and events in the direction of needed changes; and to

raise the levels of understanding and commitment to action of

individuals, voluntary organizations, businesses, institutes, and

governments.

10. Through our deliberatiuns and the testimoay of people at

the pudlic hearings we neld cn five continents, ail the

commissioners came to focvc on one central theme: many present

development trends leave increasing numbers of people poor and

vulnerable, while at the same tine deyrad:g the environment

How can such development serve next century's world of twice a

many people relying on the same environment? This realization

broadened our view of development. We came to see it not in its

restricted context of economic growth in developing countries

We came to see that a new development path was required. one that

sustained human progress not just in a few places for a tew

years, but for ths entire planet into the distant future. Thus

‘sustainable development’ becomes a goal not just for the

‘developing’ nations, but for industrial ones as well

The Interlocking Crises

11. Until recently, the planet was a large world in which human

aclivities aud their effects were neatly compartmentalized within

nations, within sectors (energy. agriculture, trade), and within

broad areas of concern (environment, economice, social). These

compartments have begun to dissolve. This applies in particular

to the various global ‘crises’ that have seized public concern,

particularly over the past decade. These are not e#parate

erines: an environmental crisis. a development crisis, an eneray

crisis. They are all one

12. The planet is passing through a period of dramatic growth

and fundamental change. Our human world of $ billion must make

room in a finite environment for another human world. The

population could stabilize at between $ and 14 billion sometime

next century, according to UN projections. More than YU per cent

of the increase will occur in the poorest countries, and 90 per

cent of thet growth iu already buceting cities

13. Economic activity has meltiplied to create a $1) trillion

world economy, and this could grow five o tenfold in the coming

halt century. Induetrial production hae grown more than

fiftyfold over tne past century, four fifths of this growth since

1980. Such figures reflect and presage profound impacte upon the

RiAasAdT

right

wie 21

The World Commiasion on Environment and Development first met

in October 1984, and published its Report 900 days later. in

April 1967. Over those few day

* The drought-triggered, environment-development crisis in

Africa peaked, putting 35 million people at risk, killing

perhaps a million.

* A leax trom a pesticides tactory in wnopal, India, Killed

more than 2,000 people and blinded and injured over 200,000

more.

+ Liquid gas tanke «xploded in Mexico City, killing 1,000 and

leaving thousands more honele

* The Chernobyl nuclear reactor explosion sent nuclear

fallout across Europe, increasing the risks of future hui

cancers.

|

{ * Agricultural chemicals, solvents, and mercury flowed into

i the Rhine River during a warehouse fire in Switzerland,

| killing millions of fin a) | threatening drinking water in

| the Federal Republic of Germany and the Netherlands.

* An estimated 60 million people died of diarrhoeal diseases

related to unsafe drinking water and malnutrition; most of

the victims were children.

biosphere. as the world invests in houses. transport. farms. and

industries. Much of the economic growth pulls raw material from

foresis, soils, seas, and waterways

14. A wainepring of economic growth is new technology, and

while this technology offers the potential for slowing the

dangerously rapid consumption of finite resources, it also

entails nign risks, including new forms of pollution and the

introduction to the planet of new variations of life forms that

could change evolutionary pathways. Meanwhile, the industries

most heavily celiant on environmental resources and most heavily

polluting are growing moot rapidly in the developing world, where

there is both more urgency for growth and less capacity to

minimize damaging side effects

1S. These related changes have locked the global economy and

global ecology together in new ways. We have in the past been

concerned about the impacts of economic growth upon the

environment. We are now forced to concern ourselves with the

impacts of ecological stress - degradation of soils, water

regimes, atmosphere, and forests upon our economic prospects

We have in the more recent past been forced to face up to 4 sharp

increase in economic interdependence among nations. We are now

forced to accustom ourselves to an accelerating ecological

interdependence among nations. Ecology and economy are becoming

ever more interwoven locally, regionally, nationally, and

globally into a eeamleee net of causes and effects

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Manual VexpensesDocument20 pagesManual VexpensesMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

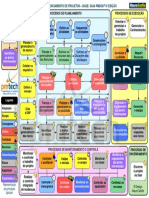

- Fluxo PMBOK 6aDocument1 pageFluxo PMBOK 6aMárcio Estevam100% (1)

- Documentação para Integração de TerceirosDocument1 pageDocumentação para Integração de TerceirosMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Installation Instruction ElevatorDocument42 pagesInstallation Instruction ElevatorMárcio Estevam100% (1)

- Proposta Flessak - ApucaranaDocument3 pagesProposta Flessak - ApucaranaMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- LED Lamp Material SheetDocument2 pagesLED Lamp Material SheetMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Sjhs2a (En)Document84 pagesSjhs2a (En)Márcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- FISPQ Óleo DegomadoDocument6 pagesFISPQ Óleo DegomadoMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Smartlink Atlas CopcoDocument1 pageSmartlink Atlas CopcoMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Manual de Bolso HP 50GDocument197 pagesManual de Bolso HP 50Gharoldquot100% (3)

- Graxa AliplexDocument1 pageGraxa AliplexMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Checklist Horímetro CompressorDocument1 pageChecklist Horímetro CompressorMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Fispq DenvertecDocument10 pagesFispq DenvertecMárcio EstevamNo ratings yet

- Spare Parts Máquina Lavagem de Piso A5Document113 pagesSpare Parts Máquina Lavagem de Piso A5Márcio EstevamNo ratings yet