Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pablico Vs Villapando

Pablico Vs Villapando

Uploaded by

Jun Jun0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views5 pagesPablkco vs villapondo

Original Title

4.-Pablico-vs-Villapando

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPablkco vs villapondo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views5 pagesPablico Vs Villapando

Pablico Vs Villapando

Uploaded by

Jun JunPablkco vs villapondo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

EN BANC

G.R. No. 147870 July 31, 2002

RAMIR R. PABLICO, petitioner,

vs.

ALEJANDRO A. VILLAPANDO, respondent.

YNARES-SANTIAGO, J.:

May local legislative bodies and/or the Office of the President, on

appeal, validly impose the penalty of dismissal from service on

erring elective local officials?

This purely legal issue was posed in connection with a dispute

over the mayoralty seat of San Vicente, Palawan. Considering that

the term of the contested office expired on June 30, 2001, 1 the

present case may be dismissed for having become moot and

academic.2 Nonetheless, we resolved to pass upon the above-

stated issue concerning the application of certain provisions of the

Local Government Code of 1991.

The undisputed facts are as follows:

On August 5, 1999, Solomon B. Maagad, and Renato M.

Fernandez, both members of the Sangguniang Bayan of San

Vicente, Palawan, filed with the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of

Palawan an administrative complaint against respondent

Alejandro A. Villapando, then Mayor of San Vicente, Palawan, for

abuse of authority and culpable violation of the Constitution. 3

Complainants alleged that respondent, on behalf of the

municipality, entered into a consultancy agreement with Orlando

M. Tiape, a defeated mayoralty candidate in the May 1998

elections. They argue that the consultancy agreement amounted

to an appointment to a government position within the prohibited

one-year period under Article IX-B, Section 6, of the 1987

Constitution.

In his answer, respondent countered that he did not appoint

Tiape, rather, he merely hired him. He invoked Opinion No. 106, s.

1992, of the Department of Justice dated August 21, 1992, stating

that the appointment of a defeated candidate within one year

from the election as a consultant does not constitute an

appointment to a government office or position as prohibited by

the Constitution.

On February 1, 2000, the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of Palawan

found respondent guilty of the administrative charge and imposed

on him the penalty of dismissal from service. 4 Respondent

appealed to the Office of the President which, on May 29, 2000,

affirmed the decision of the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of

Palawan.5

Pending respondent’s motion for reconsideration of the decision of

the Office of the President, or on June 16, 2000, petitioner Ramir

R. Pablico, then Vice-mayor of San Vicente, Palawan, took his oath

of office as Municipal Mayor. Consequently, respondent filed with

the Regional Trial Court of Palawan a petition for certiorari and

prohibition with preliminary injunction and prayer for a temporary

restraining order, docketed as SPL Proc. No. 3462. 6 The petition,

seeks to annul, inter alia, the oath administered to petitioner. The

Executive Judge granted a Temporary Restraining Order effective

for 72 hours, as a result of which petitioner ceased from

discharging the functions of mayor. Meanwhile, the case was

raffled to Branch 95 which, on June 23, 2000, denied respondent’s

motion for extension of the 72-hour temporary restraining order. 7

Hence, petitioner resumed his assumption of the functions of

Mayor of San Vicente, Palawan.

On July 4, 2000, respondent instituted a petition for certiorari and

prohibition before the Court of Appeals seeking to annul: (1) the

May 29, 2000 decision of the Office of the President; (2) the

February 1, 2000, decision of the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of

Palawan; and (3) the June 23, 2000 order of the Regional Trial

Court of Palawan, Branch 95.

On March 16, 2001, the Court of Appeals 8 declared void the

assailed decisions of the Office of the President and the

Sangguniang Panlalawigan of Palawan, and ordered petitioner to

vacate the Office of Mayor of San Vicente, Palawan. 9 A motion for

reconsideration was denied on April 23, 2001. 10 Hence, the instant

petition for review.

The pertinent portion of Section 60 of the Local Government Code

of 1991 provides:

Section 60. Grounds for Disciplinary Actions. – An elective local

official may be disciplined, suspended, or removed from office on

any of the following grounds:

xxx xxx xxx

An elective local official may be removed from office on

the grounds enumerated above by order of the proper

court. (Emphasis supplied)

It is clear from the last paragraph of the aforecited provision that

the penalty of dismissal from service upon an erring elective local

official may be decreed only by a court of law. Thus, in Salalima,

et al. v. Guingona, et al.,11 we held that "[t]he Office of the

President is without any power to remove elected officials, since

such power is exclusively vested in the proper courts as expressly

provided for in the last paragraph of the aforequoted Section 60."

Article 124 (b), Rule XIX of the Rules and Regulations

Implementing the Local Government Code, however, adds that –

"(b) An elective local official may be removed from office on the

grounds enumerated in paragraph (a) of this Article [The grounds

enumerated in Section 60, Local Government Code of 1991] by

order of the proper court or the disciplining authority

whichever first acquires jurisdiction to the exclusion of the

other." The disciplining authority referred to pertains to the

Sangguniang Panlalawigan/Panlungsod/Bayan and the Office of

the President.12

As held in Salalima,13 this grant to the "disciplining authority" of

the power to remove elective local officials is clearly beyond the

authority of the Oversight Committee that prepared the Rules and

Regulations. No rule or regulation may alter, amend, or

contravene a provision of law, such as the Local Government

Code. Implementing rules should conform, not clash, with the law

that they implement, for a regulation which operates to create a

rule out of harmony with the statute is a nullity. Even Senator

Aquilino Q. Pimentel, Jr., the principal author of the Local

Government Code of 1991, expressed doubt as to the validity of

Article 124 (b), Rule XIX of the implementing rules. 14

Verily, the clear legislative intent to make the subject power of

removal a judicial prerogative is patent from the deliberations in

the Senate quoted as follows:

xxx xxx xxx

Senator Pimentel. This has been reserved, Mr. President, including

the issue of whether or not the Department Secretary or the

Office of the President can suspend or remove an elective official.

Senator Saguisag. For as long as that is open for some later

disposition, may I just add the following thought: It seems to me

that instead of identifying only the proper regional trial court or

the Sandiganbayan, and since we know that in the case of a

regional trial court, particularly, a case may be appealed or may

be the subject of an injunction, in the framing of this later on, I

would like to suggest that we consider replacing the phrase

"PROPER REGIONAL TRIAL COURT OR THE SANDIGANBAYAN"

simply by "COURTS". Kasi po, maaaring sabihin nila na mali iyong

regional trial court o ang Sandiganbayan.

Senator Pimentel. "OR THE PROPER COURT."

Senator Saguisag. "OR THE PROPER COURT."

Senator Pimentel. Thank you. We are willing to accept that now,

Mr. President.

Senator Saguisag. It is to be incorporated in the phraseology that

will craft to capture the other ideas that have been elevated.

xxx xxx x x x.15

It is beyond cavil, therefore, that the power to remove erring

elective local officials from service is lodged exclusively with the

courts. Hence, Article 124 (b), Rule XIX, of the Rules and

Regulations Implementing the Local Government Code, insofar as

it vests power on the "disciplining authority" to remove from

office erring elective local officials, is void for being repugnant to

the last paragraph of Section 60 of the Local Government Code of

1991. The law on suspension or removal of elective public officials

must be strictly construed and applied, and the authority in whom

such power of suspension or removal is vested must exercise it

with utmost good faith, for what is involved is not just an ordinary

public official but one chosen by the people through the exercise

of their constitutional right of suffrage. Their will must not be put

to naught by the caprice or partisanship of the disciplining

authority. Where the disciplining authority is given only the power

to suspend and not the power to remove, it should not be

permitted to manipulate the law by usurping the power to

remove.16 As explained by the Court in Lacson v. Roque:17

"…the abridgment of the power to remove or suspend an elective

mayor is not without its own justification, and was, we think,

deliberately intended by the lawmakers. The evils resulting from a

restricted authority to suspend or remove must have been

weighed against the injustices and harms to the public interests

which would be likely to emerge from an unrestrained

discretionary power to suspend and remove."

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the instant petition for

review is DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., Bellosillo, Puno, Vitug, Kapunan, Mendoza,

Panganiban, Quisumbing, Sandoval-Gutierrez, Carpio, Austria-

Martinez, and Corona, JJ., concur.

You might also like

- Emergency Motion For Preliminary Injunctive Relief: Aaron Walker v. Brett KimberlinDocument3 pagesEmergency Motion For Preliminary Injunctive Relief: Aaron Walker v. Brett KimberlinJeff QuintonNo ratings yet

- Tax Referendum OrderDocument52 pagesTax Referendum OrderAdrian MojicaNo ratings yet

- Sample of Motion For ReconsiderationDocument2 pagesSample of Motion For ReconsiderationEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- PALE - Cases 31 To 40Document21 pagesPALE - Cases 31 To 40pogsNo ratings yet

- Preliminaries To The VotingDocument36 pagesPreliminaries To The VotingJennica Gyrl G. DelfinNo ratings yet

- Sample Petition For BailDocument3 pagesSample Petition For BailEis Pattad Mallonga100% (17)

- G.R. No. 195649 July 2, 2013 Casan Macode Macquiling vs. Commission On Elections, Rommel Arnado Y Cagoco, and Linog G. Balua. FactsDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 195649 July 2, 2013 Casan Macode Macquiling vs. Commission On Elections, Rommel Arnado Y Cagoco, and Linog G. Balua. FactsEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Imelda Romualdez Versus ComelecDocument4 pagesCase Digest Imelda Romualdez Versus ComelecEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Civil Pro Comparison TablesDocument9 pagesCivil Pro Comparison TablesSGTNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Digested Cases Leonen's 2012-2020Document208 pagesCivil Law Digested Cases Leonen's 2012-2020Sheryl Mae Addun Querobines100% (2)

- Counting and Appreciation of Ballots 100Document109 pagesCounting and Appreciation of Ballots 100DM DGNo ratings yet

- Calo VS RoldanDocument4 pagesCalo VS RoldanTobit Atlan100% (2)

- Criminal Procedure Case DigestDocument8 pagesCriminal Procedure Case DigestEis Pattad Mallonga100% (1)

- Dar Ao No. 08, Series of 1995Document5 pagesDar Ao No. 08, Series of 1995Eis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Efficiency Paper RuleDocument2 pagesEfficiency Paper Rulesharoncerro81No ratings yet

- Bautista v. CADocument2 pagesBautista v. CAAthena BlakeNo ratings yet

- De Jesus Vs COADocument5 pagesDe Jesus Vs COAJohn Ramil RabeNo ratings yet

- BASIC LEGAL & JUDICIAL ETHICS - Discipline of Members of The JudiciaryDocument18 pagesBASIC LEGAL & JUDICIAL ETHICS - Discipline of Members of The JudiciaryAppleNo ratings yet

- Temporary Injunction and Mandatory InjunctionDocument9 pagesTemporary Injunction and Mandatory InjunctionAbhijit PatilNo ratings yet

- Digested Oblicon CasesDocument10 pagesDigested Oblicon CasesEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Sample Affidavit of DesistanceDocument3 pagesSample Affidavit of DesistanceEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Ordinance of All ResettlementDocument7 pagesOrdinance of All ResettlementJunar PlagaNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 51 Number 1 & 2 - 05 - Pelagio T. Ricalde - Mr. Chief Justice Conception On Judicial Review P. 103-123Document21 pagesPLJ Volume 51 Number 1 & 2 - 05 - Pelagio T. Ricalde - Mr. Chief Justice Conception On Judicial Review P. 103-123Christine ErnoNo ratings yet

- LBC Courier Terms and ConditionsDocument3 pagesLBC Courier Terms and ConditionsTomas Diane LizardoNo ratings yet

- Supplemental Comment On Motion For Execution UyDocument2 pagesSupplemental Comment On Motion For Execution UyRaffy PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Squatting SyndicateDocument1 pageSquatting SyndicateLasPinasCity PoliceStationNo ratings yet

- Penera Versus ComelecDocument3 pagesPenera Versus ComelecEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Victoriano V. Elizalde Rope Workers UnionDocument2 pagesVictoriano V. Elizalde Rope Workers UnionPraisah Marjorey Picot100% (1)

- Special Adr Rules: A.M. No. 07-11-08-SCDocument82 pagesSpecial Adr Rules: A.M. No. 07-11-08-SCPatatas Sayote50% (2)

- DENR Administrative Order No 99-14Document3 pagesDENR Administrative Order No 99-14Vivian Escoto de BelenNo ratings yet

- Coa C2000-005Document2 pagesCoa C2000-005bolNo ratings yet

- Requirements - Setting Up A FoundationDocument2 pagesRequirements - Setting Up A FoundationVanessa MallariNo ratings yet

- LGC - Ra 7160Document207 pagesLGC - Ra 7160Rah-rah Tabotabo ÜNo ratings yet

- Coa M2014-009 PDFDocument34 pagesCoa M2014-009 PDFAlvin ComilaNo ratings yet

- 06 Pablico v. VillapandoDocument2 pages06 Pablico v. VillapandoALIYAH MARIE ROJONo ratings yet

- 1 19 Consti. Law 2 DigestDocument40 pages1 19 Consti. Law 2 DigestMarc Armand Balubal MaruzzoNo ratings yet

- Ibp Lawyers Id Form: Integrated Bar of The PhilippinesDocument1 pageIbp Lawyers Id Form: Integrated Bar of The PhilippinesVoltaire Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Loloy Unduran VDocument3 pagesLoloy Unduran VXian AldenNo ratings yet

- Voters Registration Act (RA 8189)Document24 pagesVoters Registration Act (RA 8189)tagabantayNo ratings yet

- Pablico v. VillapandoDocument2 pagesPablico v. VillapandoKarla BeeNo ratings yet

- Liaison OfficerDocument4 pagesLiaison Officerhelga armstrongNo ratings yet

- 7 Crebello v. Ombudsman 2019Document7 pages7 Crebello v. Ombudsman 2019joselle torrechillaNo ratings yet

- #2 Credit Transactions Lecture Notes - Articles 1999 To 2009, Pages 962 - 968 Paras 2016 - 20210303 WednesdayDocument7 pages#2 Credit Transactions Lecture Notes - Articles 1999 To 2009, Pages 962 - 968 Paras 2016 - 20210303 Wednesdayemen penaNo ratings yet

- Poe (Elamparo) - Resolution-Spa No. 15-001 (DC)Document35 pagesPoe (Elamparo) - Resolution-Spa No. 15-001 (DC)Ma Janelli Erika AguinaldoNo ratings yet

- REM CasesDocument112 pagesREM CasesConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Outline Special Civil ActionDocument10 pagesOutline Special Civil Actioncmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Handouts FMCDocument4 pagesHandouts FMCaerwincarlo4834No ratings yet

- DILG Opinion-Sanggunian Employees Disbursements, Sign Checks & Travel OrderDocument2 pagesDILG Opinion-Sanggunian Employees Disbursements, Sign Checks & Travel OrderCrizalde de DiosNo ratings yet

- Deed of Conveyance of The Reversion: Form No. 18Document2 pagesDeed of Conveyance of The Reversion: Form No. 18Sudeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Violation of Verification and CertificationDocument6 pagesViolation of Verification and CertificationWreigh Paris100% (1)

- Sec 45 LGCDocument6 pagesSec 45 LGCWelbert SamaritaNo ratings yet

- 06 Mock - Verbal (2) - Class Sinagtala 2023Document9 pages06 Mock - Verbal (2) - Class Sinagtala 2023Elixer De Asis VelascoNo ratings yet

- Rule 6 Interim Rules of Procedure For Intra-Corporate Controversies PDFDocument2 pagesRule 6 Interim Rules of Procedure For Intra-Corporate Controversies PDFiptrinidadNo ratings yet

- Sec Green Lane FormDocument8 pagesSec Green Lane FormZena E. SugatainNo ratings yet

- PRO Version: Are You A Developer? Try Out TheDocument4 pagesPRO Version: Are You A Developer? Try Out TheLala LanibaNo ratings yet

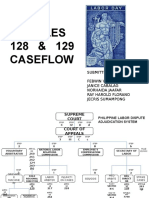

- Labor HierarchyDocument12 pagesLabor HierarchyfebwinNo ratings yet

- Summons ReportDocument19 pagesSummons ReportylessinNo ratings yet

- DOJ Opinion No. 52, S96 (Conversion and Reclassification)Document2 pagesDOJ Opinion No. 52, S96 (Conversion and Reclassification)Dred OpleNo ratings yet

- LFW 2Document35 pagesLFW 2JasOn EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Yamson Et Al. v. Castro PDFDocument26 pagesYamson Et Al. v. Castro PDFjagabriel616No ratings yet

- Senga Sales SyllabusDocument2 pagesSenga Sales SyllabusPochoy Mallari0% (1)

- Judicial Jurisdiction and Forum Non ConviniensDocument3 pagesJudicial Jurisdiction and Forum Non ConviniensDave OcampoNo ratings yet

- Sameer Overseas Placement Agency, Inc. v. CabilesDocument30 pagesSameer Overseas Placement Agency, Inc. v. CabilesLance Lagman100% (1)

- Nov 2017 - PDFDocument4 pagesNov 2017 - PDFSam MaulanaNo ratings yet

- USPF LEX Consti and By-LawsDocument9 pagesUSPF LEX Consti and By-LawsbelteshazzarNo ratings yet

- Revised 2023 T GMCDocument2 pagesRevised 2023 T GMCArial BlackNo ratings yet

- ReductionDocument2 pagesReductionPeter Carlo DavidNo ratings yet

- Guidelines in Preparing and Issuing Supplemental Report - February272007Document3 pagesGuidelines in Preparing and Issuing Supplemental Report - February272007JennPete RefolNo ratings yet

- NTC v. Hamoy, Jr. (Reassignment) 2009Document7 pagesNTC v. Hamoy, Jr. (Reassignment) 2009Dael GerongNo ratings yet

- Bantay KorapsyonDocument20 pagesBantay KorapsyonAirah GolingayNo ratings yet

- CERT. OF CANDIDACY - ForDocument13 pagesCERT. OF CANDIDACY - Forwwe_jhoNo ratings yet

- PCU - LMT - Civil Law - 2019Document24 pagesPCU - LMT - Civil Law - 2019SJ LiminNo ratings yet

- Pablico V VillapandoDocument2 pagesPablico V VillapandoJohn YeungNo ratings yet

- Pub - Corp FDocument25 pagesPub - Corp FshevionNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 147870 July 31, 2002 RAMIR R. PABLICO, Petitioner, ALEJANDRO A. VILLAPANDO, Respondent. Ynares-Santiago, J.Document4 pagesG.R. No. 147870 July 31, 2002 RAMIR R. PABLICO, Petitioner, ALEJANDRO A. VILLAPANDO, Respondent. Ynares-Santiago, J.shhhgNo ratings yet

- Pablico Vs VillapandoDocument6 pagesPablico Vs VillapandoJan Kenrick SagumNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Pablico vs. VillapandoDocument16 pagesFacts:: Pablico vs. VillapandozNo ratings yet

- Facts:: People of The Philippines, Vs Capt. Florencio O. GasacaoDocument4 pagesFacts:: People of The Philippines, Vs Capt. Florencio O. GasacaoEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Graduate School of LAW: San Beda CollegeDocument10 pagesGraduate School of LAW: San Beda CollegeEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Atong Paglaum, Inc. Vs Commission On ElectionsDocument6 pagesAtong Paglaum, Inc. Vs Commission On ElectionsEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Loving v. Virginia-Napocor v. JocsonDocument14 pagesLoving v. Virginia-Napocor v. JocsonEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Ara Tea Versus ComelecDocument6 pagesAra Tea Versus ComelecEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- TANADA Versus ANGARA Case DigestDocument15 pagesTANADA Versus ANGARA Case DigestEis Pattad Mallonga67% (3)

- Board of Criminology-SBDocument2 pagesBoard of Criminology-SBEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- LIST Crim ProDocument1 pageLIST Crim ProEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- People vs. JumawanDocument2 pagesPeople vs. JumawanEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing - Full Text of CasesDocument110 pagesLegal Writing - Full Text of CasesEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Asari Yoko V Kee BocDocument1 pageAsari Yoko V Kee BocEis Pattad MallongaNo ratings yet

- Stutts v. Rapid Cool Misting SystemsDocument6 pagesStutts v. Rapid Cool Misting SystemsPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Labor ReviewerDocument26 pagesLabor ReviewerMary Rhodette LegramaNo ratings yet

- Perez v. Madrona, 668 SCRA 696Document7 pagesPerez v. Madrona, 668 SCRA 696Trebx Sanchez de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 01 Ronquillo v. Court of AppealsDocument7 pages01 Ronquillo v. Court of AppealsasdfghsdgasdfaNo ratings yet

- Violent Crown Trademark SuitDocument50 pagesViolent Crown Trademark SuitAnonymous Pb39klJNo ratings yet

- Chavez Vs - PEA DigestDocument40 pagesChavez Vs - PEA DigestChristopher AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- 36 Lacurom v. Jacoba, 484 SCRA 206, A.C. No. 5921, March 10, 2006Document7 pages36 Lacurom v. Jacoba, 484 SCRA 206, A.C. No. 5921, March 10, 2006EK ANGNo ratings yet

- Unilever vs. Proctor & GambleDocument7 pagesUnilever vs. Proctor & Gambled-fbuser-49417072No ratings yet

- Abs CBN Broadcasting Corp Vs Phil Multimedia - G.R. Nos. 175769-70Document21 pagesAbs CBN Broadcasting Corp Vs Phil Multimedia - G.R. Nos. 175769-70Charmaine Valientes CayabanNo ratings yet

- Amsted Industries v. Tianrui Group Foundry Company Et. Al.Document9 pagesAmsted Industries v. Tianrui Group Foundry Company Et. Al.PriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Metrolab Industries, Inc. vs. Roldan-Confesor, G.R. No. 108855, February 28, 1996, 254 SCRA 182Document22 pagesMetrolab Industries, Inc. vs. Roldan-Confesor, G.R. No. 108855, February 28, 1996, 254 SCRA 182jonbelzaNo ratings yet

- 1 Boncodin V National Power Corp Employees Consolidated UnionDocument13 pages1 Boncodin V National Power Corp Employees Consolidated UnionAlvin Earl NuydaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Arbitrator Relief - A Practical Guide (Matthew Hodgson, Jae Hee Suh & Kellie Yi)Document9 pagesEmergency Arbitrator Relief - A Practical Guide (Matthew Hodgson, Jae Hee Suh & Kellie Yi)Zviagin & CoNo ratings yet

- Compiled Cases - Easement and NuissanceDocument91 pagesCompiled Cases - Easement and NuissanceSunshine EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Mutual Confidentiality and Nondisclosure Agreement 1Document5 pagesMutual Confidentiality and Nondisclosure Agreement 1vart1992No ratings yet

- Metrolab Industries, Inc. vs. Roldan-ConfesorDocument12 pagesMetrolab Industries, Inc. vs. Roldan-ConfesorT Cel MrmgNo ratings yet

- (PAGCOR) vs. Fontana Development CorporationDocument6 pages(PAGCOR) vs. Fontana Development CorporationGeenea VidalNo ratings yet

- 3.3 Catungal v. RodriguezDocument8 pages3.3 Catungal v. RodriguezBeltran KathNo ratings yet

- BASF CORPORATION v. SYNGENTA CROP PROTECTION, INC. Et Al - Document No. 9Document2 pagesBASF CORPORATION v. SYNGENTA CROP PROTECTION, INC. Et Al - Document No. 9Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Powers and Functions of The Commission On ElectionsDocument10 pagesPowers and Functions of The Commission On ElectionsOrange Zee MelineNo ratings yet

- 08 Ambrosio V SalvadorDocument1 page08 Ambrosio V SalvadorevgciikNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Temporary Injunction: Dalpat Kumar V/s Pralhad Singh, AIR 1993 SC 276Document14 pagesChapter 5: Temporary Injunction: Dalpat Kumar V/s Pralhad Singh, AIR 1993 SC 276sazib kaziNo ratings yet

- Unduran V AberasturiDocument10 pagesUnduran V AberasturiJade Palace TribezNo ratings yet