Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Internet Gaming Disorder in Lebanon Relationships PDF

Uploaded by

John Rafael B. GarciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Internet Gaming Disorder in Lebanon Relationships PDF

Uploaded by

John Rafael B. GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

FULL-LENGTH REPORT Journal of Behavioral Addictions

DOI: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.16

Internet gaming disorder in Lebanon: Relationships with age, sleep habits,

and academic achievement

NAZIR S. HAWI1, MAYA SAMAHA1* and MARK D. GRIFFITHS2

Faculty of Natural and Applied Sciences, Notre Dame University – Louaize, Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon

1

2

The International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

(Received: August 2, 2017; revised manuscript received: December 7, 2017; accepted: December 10, 2017)

Background and aims: The latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

included Internet gaming disorder (IGD) as a disorder that needs further research among different general

populations. In line with this recommendation, the primary objective of this was to explore the relationships

between IGD, sleep habits, and academic achievement in Lebanese adolescents. Methods: Lebanese high-school

students (N = 524, 47.9% males) participated in a paper survey that included the Internet Gaming Disorder Test and

demographic information. The sample’s mean average age was 16.2 years (SD = 1.0). Results: The pooled prevalence

of IGD was 9.2% in the sample. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis demonstrated that IGD was associated

with being younger, lesser sleep, and lower academic achievement. While more casual online gamers also played

offline, all the gamers with IGD reported playing online only. Those with IGD slept significantly less hours per night

(5 hr) compared with casual online gamers (7 hr). The school grade average of gamers with IGD was the lowest

among all groups of gamers, and below the passing school grade average. Conclusions: These findings shed light on

sleep disturbances and poor academic achievement in relation to Lebanese adolescents identified with IGD. Students

who are not performing well at schools should be monitored for their IGD when assessing the different factors behind

their low academic performance.

Keywords: Internet gaming disorder, academic performance, sleep, video game addiction, gaming addiction,

adolescents

INTRODUCTION among older adolescents and emerging adults. For instance,

in Germany, an IGD prevalence rate of 1.2% was observed

Since the early 2000s, there has been a significant increase in a representative sample of 11,003 young to older ado-

in the number of studies providing empirical evidence of the lescents ranging in age from 13 to 18 years using the Video

existence of problematic gaming and gaming addiction Game Dependency Scale (CSAS-II; Rehbein et al., 2015). A

(Kuss & Griffiths, 2012). Due to this, the latest (fifth) study that included seven European countries reported a

edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental prevalence rate of 5.3% in a sample of 12,938 adult gamers

Disorders (DSM-5) included Internet gaming disorder using the Assessment of Internet and Computer Game

(IGD) in Section III and stated that IGD is a condition that Addiction – Gaming Module (AICA-S-gaming) (Müller

requires further study before being included in the main text et al., 2015). In Slovenia, an IGD prevalence rate of

(American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). With IGD 2.5% was obtained in a sample of 1,071 gamers aged

being a new concept, it is still being debated with many 13–14 years old using the Internet Gaming Disorder

issues and concerns raised over, whether it is a genuine Scale – Short-Form (IGDS9-SF; Pontes, Macur, & Griffiths,

disorder or not, and if it is genuine, what criteria are the most 2016). The Game Addiction Scale (Lemmens, Valkenburg,

suitable for diagnosis (Kuss, Griffiths, & Pontes, 2017a, & Peter, 2009) was used in European countries reporting an

2017b). IGD prevalence rate of 1.4% in a Norwegian representative

Despite the availability of several IGD assessment tools sample of 3,035 adult gamers (16–71 years old) (Wittek

(Lopez-Fernandez, Honrubia-Serrano, Baguley, & Griffiths, et al., 2015) and a rate of 7.6% of problematic users

2014; Pápay et al., 2013; Sanders & Williams, 2016; Wu, of ages below 19 years in a German representative sample

Lai, Yu, Lau, & Lei, 2016), research results collectively of 580 adolescent gamers (Festl et al., 2013). In the

indicated that the IGD is a global phenomenon (Ko, 2014; Netherlands, in a nationally representative study of

Müller et al., 2015; Wittek et al., 2015) with pooled preva-

lence ranging from 1.2% (Rehbein, Kliem, Baier, Mößle, & * Corresponding author: Maya Samaha; Faculty of Natural and

Petry, 2015) to 7.6% (Festl, Scharkow, & Quandt, 2013) in Applied Sciences, Notre Dame University – Louaize, PO Box 72

nationally representative samples. Research also appears to Zouk Mikael, Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon; Phone: +961 9 208 749;

indicate that the highest prevalence rates of IGD are found Fax: +961 9 225 164; E-mail: msamaha@ndu.edu.lb

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author and source are credited.

© 2018 The Author(s)

Hawi et al.

4,559 adolescent gamers aged 13–16 years, a prevalence grade point averages (GPAs; Jackson, Von Eye, Witt, Zhao,

rate of 1.5% was reported using the Compulsive Internet & Fitzgerald, 2011). Recent studies have confirmed this

Use Scale (Van Rooij, Schoenmakers, Vermulst, Van Den finding from many parts of the world including Germany

Eijnden, & Van De Mheen, 2011). Table 1 includes (Rehbein et al., 2015), Taiwan (Yeh & Cheng, 2016),

these and other selected epidemiological studies that have Lebanon (Hawi & Samaha, 2016), Norway (Brunborg,

investigated IGD. Mentzoni, & Frøyland, 2014), Iran (Haghbin, Shaterian,

In addition to prevalence, researchers have been Hosseinzadeh, & Griffiths, 2013), and the United States of

interested in identifying trends and negative impact of IGD America (USA) (Schmitt & Livingston, 2015; Wentworth &

(Kim et al., 2016; Müller et al., 2015) including academic Middleton, 2014).

achievement, time spent gaming, money spent on gaming, As for time spent gaming, a study conducted in Hong

sleep duration, and impact on job/education and other Kong on a sample of 503 adolescents showed that of total

leisure activities. A number of studies have demonstrated gamers, 22.9% and 36.6% played more than 3 hr on week-

the negative impact of gaming on academic achievement days and weekends, respectively, and 31.2% and 32% played

(Van Rooij et al., 2011). For instance, a longitudinal study more than 1 hr on weekdays and weekends, respectively

of 482 American adolescents with average age of 12 years (Wang et al., 2014). Studies also report that gamers tend

reported that video game playing was associated with lower to play online games rather than offline. For instance, the

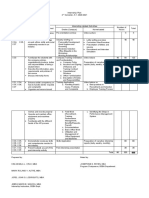

Table 1. International comparison of prevalence rates of video game addiction/Internet gaming disorder

Nationally

Sample Prevalence representative

Reference Scale used size Age rate (%) Country sample

Pontes, Macur, and Internet Gaming Disorder 1,071 M = 13 2.5 Slovenia Yes

Griffiths (2016) Scale – Short-Form (IGDS9-SF)

Fuster et al. (2016) Spanish version IGD-20 Test 1,074 12–58 2.6 Spain No

Pontes and Griffiths IGDS9-SF 509 10–18 Not Portugal No

(2016) available

Khazaal et al. (2016) 7-item Game Addiction Scale (GAS) 5,983 M = 20 2.3 Switzerland No

Kim et al. (2016) The suggested wordings of the DSM-5 3,041 20–49 13.8 Korea No

criteria was applied

Rehbein et al. (2016) Gaming usage and time questions 3,073 M = 49 4.2 Germany Yes

Lemos, Cardoso, Video Game Addiction Test (VAT) 384 18–24 Not Brazil No

and Sougey (2016) available

Rehbein et al. (2015) CSAS-II 11,003 13–18 1.16 Germany Yes

Wittek et al. (2015) 7-item Game Addiction Scale for 3,035 16–74 1.4 Norway Yes

Adolescents (GAS)

Müller et al. (2015) Assessment of Internet and Computer 12,938 14–17 1.6 7 European Yes

game Addiction–Gaming Module countries

(AICA-S-gaming)

Pontes et al. (2014) Internet Gaming Disorder Test 1,003 16–58 5.3 57 No

(IGD20-Test) countries

Lopez-Fernandez Problematic Videogame Playing Scale 1,132 11–18 7.7 Spain No

et al. (2014) 1,224 14.6 Great

Britain

King, Delfabbro, Pathological Video Gaming (PVG) 1,287 12–18 1.8 Australia No

Zwaans, and

Kaptsis (2013)

Spekman, Konijn, Problematic gaming behavior 1,004 11–18 8.57 Netherlands No

Roelofsma, and

Griffiths (2013)

Festl et al. (2013) 7-item Game Addiction Scale for 580 14–18 7.6 Germany Yes

Adolescents (GAS)

Brunborg et al. Game Addiction Scale for Adolescents 1,320 M = 13.6 4.2 Norway Yes

(2013) (GASA)

Van Rooij et al. Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) 4,559 13–16 1.5 Netherlands Yes

(2011)

Choo et al. (2010) Pathological Video Gaming Scale 2,998 M = 11.2 8.7 Singapore No

Grüsser, Adapted from WHO criteria for 7,069 21.1 11.9 Germany No

Thalemann, and substance dependence

Griffiths (2007)

Johansson and Internet Addiction Test 3,237 12–18 2.7 Norway Yes

Götestam (2004)

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

IGD in Lebanon: Sleep and academic achievement

aforementioned Hong Kong study reported that (a) playing SD = 1.0). Participation in the survey was purely voluntary

online multiplayer games was the most preferred type of and the overall response rate was 25%, yielding an adequate

game, (b) online single player games ranked second, and sample size (524 participants). There was a lower ratio of

(c) a minority preferred playing offline casual games (Wang male (47.9%) to female respondents. Participants were

et al., 2014). Online gaming can result in extended periods of recruited from 10 schools operating in different administra-

gaming for which a small minority can be problematic and tive governorates across Lebanon. Schools where English

addictive. In addition, evidence suggests that some game was a medium of instruction were targeted (because the

genres are more addictive than others, such as role-playing survey was in English). Following the school’s approval to

games and first-person shooter games (Festl et al., 2013; collect the data, the “pen and paper” survey was administered

Lemmens & Hendriks, 2016; Na et al., 2017; Rehbein, Staudt, in classrooms in the presence of class instructors.

Hanslmaier, & Kliem, 2016; Sanders & Williams, 2016).

Excessive online gaming has also been shown to reduce Measures

gamers’ sleep duration and/or result in deteriorating sleep

quality (Demirci, Akgönül, & Akpinar, 2015; Rehbein et al., The survey questionnaire was self-report, in English, and

2015), especially in adolescents (Achab et al., 2011; Arora, handed out on paper copy. It included two sections. The first

Broglia, Thomas, & Taheri, 2014; Lam, 2014). A recent section collected demographic information, including parti-

study reported that 28% of participants with sleep problems cipant’s age, gender, grade average, starting age of Internet

have IGD (Satghare et al., 2016). The authors’ follow-up of gaming, amount of time spent gaming online and offline on

some gamers suggest that they stay awake longer than the weekdays and weekends, typical sleep duration and whether

recommended sleep guidelines or awake early from sleep to the individual woke up during the night to continue gaming,

continue playing either to advance to the next level in the and money spent on Internet gaming.

game, to simply sustain the current game level, and/or for The second section included the Internet Gaming Disor-

pleasure. Furthermore, some studies have reported that der Test (IGD-20 Test; Pontes, Kiraly, Demetrovics, &

gamers spend varying amounts of money to purchase Griffiths, 2014). This scale reflects the nine criteria of IGD

additional lives, cheats, virtual weapons, gadgets, and/or as stated in the DSM-5 and incorporates the theoretical

accessories to gain advantage or just for the fun of game framework of the components model of addiction (Griffiths,

playing (Cleghorn & Griffiths, 2015). In the sample of the 2005). It is a validated and well-established scale that has

aforementioned Hong Kong study, around 40% reported been used in many studies and translated to Spanish,

having spent money on gaming, of which 3.6% spent above Portuguese, and Arabic (Fuster, Carbonell, Pontes, &

US $65, and 9.9% spent between US $25 and $64, monthly Griffiths, 2016; Hawi & Samaha, 2017c; Pontes & Griffiths,

(Wang et al., 2014). In addition, it has also been noted in 2016). Participants rated the 20 items on a 5-point Likert

many studies that gender (being male) and age (being scale: 1 (“strongly disagree”), 2 (“disagree”), 3 (“neither

younger) correlate with the IGD (Hawi & Rupert, 2015; agree nor disagree”), 4 (“agree”), and 5 (“strongly agree”).

Hawi & Samaha, 2017a, 2017b; Rehbein et al., 2016; In the process of validating IGD assessment scales and

Samaha & Hawi, 2017; Wittek et al., 2015). particularly the assessment of criterion-related validity, the

The aim of this study was to explore the extent to which association between scale score and time spent gaming time

age, sleep habits, and academic achievement explain a was analyzed (Donati, Chiesi, Ammannato, & Primi, 2015;

statistically significant amount of variance in IGD among Festl et al., 2013). In the study conducted by Pontes, Kiraly,

high-school adolescents (Griffiths, 2014) in a population Demetrovics, and Griffiths (2014), which included 57

that has never been previously studied (i.e., Lebanese teen- countries, the IGD-20 Test scores positively and strongly

agers). Another aim was to determine the prevalence of IGD correlated with weekly gameplay time (r = .77, p < .001).

in the study’s Lebanese sample and identify variables A similar result was recently obtained in Spain (r = .42,

associated with IGD to contribute to knowledge in this field p < .01) (Fuster et al., 2016) and Portugal (r = .36, p < .01)

of study as recommended by DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Despite (Pontes & Griffiths, 2016). In this study, the IGD-20

the influence of external factors, such as the Lebanese Test scores positively and strongly correlated with weekly

culture and political environment, a better understanding gameplay (r = .58, p < .001). In addition, in this study, the

of the predictors of IGD in different cultures is another step IGD-20 Test demonstrated excellent internal consistency

toward helping those who provide treatment and rehabilita- (Cronbach’s α = .915).

tion for those with clinically significant impairment

(Griffiths, 2014; Petry & O’Brien, 2013). Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS,

METHODS version 20.0 Chicago, IL, USA). The major aim of this

research was analyzed using hierarchical multiple regres-

Participants and procedure sion. Prior to regression analyses, preliminary analyses

were first conducted to ensure that there was no viola-

The present investigation was a cross-sectional study tion of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multi-

carried out in 2016 at 10 Lebanese high schools based on collinearity, and homoscedasticity. No violations were

voluntary participation of students. A total of 2,096 found. In addition to regression analysis, descriptive

students from grades 10, 11, and 12 (aged 15–19 years) statistics and Pearson product moment correlations were

received the questionnaire (mean age = 16.2 years, carried out.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Hawi et al.

Ethics Prevalence and patterns in Internet gaming

Following the approval of the Research Ethics Committee at A total of 98.0% of participants used more than one platform

Notre Dame University, Louaize, the research study was for online gaming, and 61.3% used three or more platforms.

conducted including the distribution of the survey question- As assessed by the IGD-20 Test, 9.2% of respondents

naire to schools. After receiving written informed parental belonged to the IGDG, 35.7% to the RIGDG, and 55.1%

consent, students were allowed to fill the questionnaires on a to the CGG. The average daily playtime of gamers in this

voluntary basis. study was 2.2 hr/day. It is noteworthy that the average

gaming time spent online doubled on weekends compared to

RESULTS weekdays within all three groups. In addition, the maximum

number of hours gaming online increased from 7 hr/day on

The sample’s mean average age was 16.2 years (SD = 1.0). weekdays to 14 hr/day on weekends. Among groups, the

The average number of years that participants reported average time spent gaming online on weekdays increased

online gaming was 7.75 years (SD = 2.9). Participants were from 1.7 hr/day within the CGG to 2.5 hr/day within the

classed into three groups. The following notations are used RIGDG to 3.6 hr/day within the IGDG. In addition, the

to distinguish between the three different groups studied: average time spent gaming online at weekends followed a

Internet Gaming Disorder Group (IGDG; scoring 71 or more similar pattern (Table 2). Furthermore, results showed that

on the IGD-20), at-risk of IGDG (RIGDG; scoring between the percentages of respondents, in both the IGDG and the

50 and 70 on the IGD-20), and casual gaming group (CGG; RIGDG, within grades 10, 11, and 12, were 50.0%, 34.1%,

scoring below 50 on the IGD-20) representing those who and 15.9%, respectively. The higher the grade level, the

did not meet IGD criteria. lower the percentage of participants with IGD.

Table 2. Prevalence and trends of predictors of IGD in Lebanese high-school students (N = 524)

IGDG RIGDG CGG Total

%

Prevalence 9.2 35.7 55.1 100

Hours/day

Average Internet gaming playtime

Weekdays (SD) 3.6 (1.9) 2.5 (1.4) 1.7 (1.2) 2.2 (1.4)

Weekends (SD) 8.1 (3.8) 5.9 (3.5) 3.4 (2.1) 4.7 (3.3)

%

Offline versus online Internet gaming playtime (within group)

Offline 11.1 42.9 53.7 45.9

Online 88.9 45.7 38.9 45.9

Both 0.0 11.4 7.4 8.2

Hours/night

Sleep duration (SD) 4.9 (2.7) 6.9 (1.6) 7.1 (1.5) 6.9 (1.7)

%

Sleep disturbance (within group)

Sometimes 100.0 42.9 13.0 31.6

Never 0.0 57.1 87.0 68.4

$

Monthly spending on Internet gaming

Average (SD) 74.4 (110.3) 20.25 (25.9) 12.4 (40.1) 21.9 (51.5)

Range 0–350 0–100 0–250 0–350

Grade point average out of 20

Academic achievement

Average (SD) 10.5 (3.1) 12.1 (3.2) 13.4 (2.8) 12.7 (3.1)

%

Platforms of Internet gaming (within group)

Mobile phones 88.9 97.1 87.0 90.8

Computers 55.6 71.4 63.0 65.3

Game consoles 55.6 65.7 66.7 65.3

Tablets 33.3 68.6 64.8 63.3

Note. SD: standard deviation; IGDG: group of participants identified with Internet gaming disorder; RIGDG: group of participants identified

at-risk of Internet gaming disorder; CGG: Group of participants identified as casual players.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

IGD in Lebanon: Sleep and academic achievement

The average time spent online gaming of the CGG were within accepted limits indicating that there was no

increased from 1.7 hr/day on weekdays to 3.4 hr/day on multicollinearity among factors. More specifically, tolerance

weekends. The average time spent online gaming at week- values ranged between 0.90 and 0.96, and VIF values

ends of the CGG (3.4 hr/day) matched that of IGDG on ranged between 1.0 and 1.1 (much below the threshold 3).

weekdays (3.4 hr/day). At first glance, it is tempting to Consequently, the assumption of multicollinearity was met

conclude that some CGG gamers on weekends should be (Coakes, 2005). In addition, the Mahalanobis distance scores

classified as IGDG. However, the time spent online gaming indicated that there were no multivariate outliers. Moreover,

was not strongly correlated with IGD, otherwise participants residual and scatter plots indicated that the assumptions of

from the CGG who played as much as IGDG would have normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were all met (Hair,

been identified with IGD using the IGD-20 Test. CGG Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 1998). Following this, a

participants who doubled their time spent online gaming at four-stage hierarchical multiple regression was carried out to

weekends did so for entertainment purposes and not con- assess the extent to which gender, age, sleep duration, sleep

trolled by disorder criteria as it is the case with the IGDG. disturbance, and academic achievement predicted levels of

Table 2 shows a clear change in the pattern of offline and IGD among the participants (as assessed using the IGD-20).

online usage. More gamers within the CGG played offline, Gender was entered at step 1 of the regression, age was entered

whereas gamers in the RIGDG played online rather than at step 2, sleep duration and sleep disturbances at step 3, and

offline. Eight times as many gamers in the IGDG played academic achievement at step 4. The regression analysis results

online rather than offline, and none in the IGDG played are reported in Table 3. The hierarchical multiple regression

offline games at all. With regard to sleep duration, the average demonstrated that at step 1, gender was not a significant

number of hours of sleep per night was 7.1 hr within the CGG contributor to the regression model, although it accounted for

and 4.9 hr within the IGDG. The results also found that 3.5% of the variation in IGD (Table 3). Introducing age

13.0% of the CGG gamers woke up from their sleep during explained an additional 16.5% of the variation in IGD, and

the night to continue gaming compared with 42.9% of the this change in R2 was significant [F(1, 522) = 6.201, p < .05].

RIGDG gamers and 100.0% of the IGDG. In addition, the Adding sleep duration and sleep disturbance to the regression

average monthly spending on Internet gaming rose from US model explained an additional 23.3% of the variation in IGD

$12.40 within the CGG to US $20.25 within the RIGDG, and and this change in R2 was also significant [F(3, 520) = 10.816,

to US $74.40 within the IGDG. GPA (of over 20) went down p < .001]. Finally, the addition of academic achievement to

to 13.4 within the CGG, to 12.1 within the RIGDG, and to the regression model explained an additional 9.0% of the

10.5 within the IGDG (Table 2). variation in IGD and this change in R2 was again significant

[F(4, 514) = 12.804, p < .001]. In sum, four predictors (age,

Relationship between IGD, gender, age, sleep habits, and sleep duration, sleep disturbance, and academic achievement)

academic achievement together accounted for an additional 48.8% of the variance in

IGD after controlling for gender. The beta values for sleep-

The sample size was adequate for hierarchical regression related measures were higher than age and academic achieve-

analysis as only five independent variables were investi- ment, with sleep disturbance having the greatest influence on

gated (Tabachnick, Fidell, & Osterlind, 2001). None of IGD (Table 3). Results demonstrated that the risk of IGD in

the independent variables correlated, except for a weak adolescence was increased by being younger, having lower

association between gender and sleep disturbance. The col- academic achievement, having lower sleep duration, and

linearity statistics tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) waking up more during the night to continue gaming.

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression of predictors of Internet Gaming Disorder in Lebanese high-school students (N = 524)

Predictor variables β t R R2 R2 ΔF

Step 1 .035 .001 −.005 0.199

Gender −0.035 −0.446

Step 2 .200 .040 .040 6.201*

Gender −0.025 −0.310

Age −0.199 −2.490*

Step 3 .433 .187 .187 10.816***

Gender 0.020 0.245

Age −0.244 −3.032**

Sleep duration −0.212 −2.766**

Sleep disturbance 0.346 4.376***

Step 4 .523 .274 .274 12.804***

Gender 0.101 1.330

Age −0.218 −2.850**

Sleep duration −0.212 −2.766**

Sleep disturbance 0.346 4.376***

Academic achievement −0.183 −2.455*

Note. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Hawi et al.

DISCUSSION In this study, the school GPA of the IGD group (Table 2)

was below the passing grade and much lower than the GPAs

This study examined the relationships between IGD and of those RIGD and the CGG. Other studies have reported that

other variables (age, sleep-related factors, and academic participants with IGD had poorer academic achievement in

achievement) among Lebanese adolescents. The results Singapore (Choo et al., 2010), USA (Jackson et al., 2011),

showed that 9.2% of the study’s sample were classed as Norway (Brunborg et al., 2014), and Germany (Rehbein et al.,

having IGD using the IGD-20 Test. The prevalence of IGD 2015). This finding is likely explained by the large amount

in this study is above midrange among those reported in of time spent allocated to gaming (Kuss & Griffiths, 2012)

other studies (Table 1), with a range between 1.2% in especially during study days, which in turn may lead to

Germany (Rehbein et al., 2015) and a 14.6% in the United lack of in-class concentration due to sleep deprivation

Kingdom (Lopez-Fernandez et al., 2014). One possible (Ko, 2014). This study found that 92.3% of participants

reason for the high prevalence rate of IGD may have been with IGD reported that they are preoccupied with Internet

due to the age of the sample, because IGD appears to be gaming, and of these participants, 75% reported that they

more prevalent among older adolescents and emerging wake up during the night to continue gaming. This state of

adults (Griffiths, Kuss, & Pontes, 2016). This variance in mind, whereby a gamer is either gaming or thinking about

studies’ results may also be explained by one or more of the gaming all the time, can in some cases lead to neglect of

following: (a) use of different scales to assess the IGD day-to-day responsibilities at school and home. Sleep-

(Griffiths, 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Király, Nagygyörgy, deprived participants, whether in quantity or quality,

Griffiths, & Demetrovics, 2014; Schmitt & Livingston, cannot focus on their studies and are therefore unable to

2015); (b) use of same scale, but using different cut-off learn efficiently. This phenomenon builds upon existing

thresholds (Rehbein et al., 2015); (c) employment of differ- studies showing how academic achievement is negatively

ent sampling procedures (Sanders & Williams, 2016); affected by different technological addictions (Samaha &

(d) selection of samples differing in their characteristics Hawi, 2016) and in particular by the excessive gaming

(Rehbein et al., 2015; Sanders & Williams, 2016; Wentworth (Jackson et al., 2011). Finally, the percentage of gamers

& Middleton, 2014); and/or (e) collection of data at different who played online in this study’s sample (45.9%) was

times of the year (Griffiths, 2014; Kim et al., 2016). lower than that of a similar Canadian sample (52.8%)

Similar to many studies, the study’s sample included (Sanders & Williams, 2016).

more gamers classed as at-risk of IGD (RIGD) (35.7%) than

gamers classed with IGD (9.2%) (Müller et al., 2015; Wittek Limitations and recommendations

et al., 2015). While the average daily playtime of gamers in

this study (2.2 hr/day) was very close to that of a Portuguese The main limitations of this study were its cross-sectional

sample (Pontes & Griffiths, 2016), it was lower than that of a design, the use of a non-representative sample, the use of

Singaporean sample (2.9 hr/day) (Choo et al., 2010), Lebanese schoolchildren only, and the use of self-report

but higher than that of a German sample (1.6 hr/day) data. All of these methodological issues have well-known

(Rehbein et al., 2015). The IGDG’s average daily playtime biases (e.g., social desirability bias and recall bias) and

(8.1 hr/day) was much higher than that of a German sample shortcomings (e.g., non-generalizability to other samples

(6.3 hr/day) (Rehbein et al., 2015). Similar to this study, an and cultures). Another limitation is that the IGD-20 Test was

investigation conducted on a South Korean sample reported developed and validated using a young adult sample and not

that the those with IGD spent more hours a week gaming on older adolescents. The use of a scale developed for adults

compared with all the rest (Kim et al., 2016) and the average may have affected the prevalence scores when used by older

time spent gaming doubled at weekends for all subgroups age adolescents. In future studies, a scale designed specifi-

within the sample (Hawi, 2012). It is worth noting that this cally for adolescents would be of benefit to overcome this

study was conducted in May, which was toward the end of limitation. All studies cited in this paper also used cross-

the school year, with a noticeable increase of homework and sectional design for its practicality and convenience (as was

exams. It was anticipated that the amount of time spent the case in this study); therefore, longitudinal studies are

gaming would be much higher during holidays and summer needed to determine the causal relationships between the

vacation. As the data were collected during school days, the different variables, as such associations found in this and

only period for participants to carry out their gaming was other studies can go in both directions. In particular, evi-

before and after school. In addition, massively multiplayer dence is needed to determine whether IGD causes low

games involves gamers from different time zones to keep academic achievement or vice versa. It should also be noted

building their characters, which can lead to sleep deprivation that the response rate was low (25%) and this also needs

(Achab et al., 2011) with some gamers who avoid logging taking into account when considering the results. The low

off and become preoccupied with minimizing possible response rate may have been because (a) participation was

losses. Probably for the aforementioned reasons, all gamers purely voluntary, and/or (b) the English language skill

assessed with IGD reported that sometimes they woke up among students was not sufficient to answer the survey

during the night to continue gaming online (Rehbein et al., questions. Finally, future research should target adolescents

2015). This result confirms previous studies that reported from various cultures preferably different countries and

gaming addicts refrain from sleeping to gain more time in compare results. However, this study adds to the literature,

the virtual world (Bartel & Gradisar, 2017; Lam, 2014; because it is one of the very few to be carried out in

Satghare et al., 2016; Young, 2009). Lebanon.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

IGD in Lebanon: Sleep and academic achievement

CONCLUSIONS Psychology, 16(1), 115–128. doi:10.1080/15213269.2012.

756374

The DSM-5 introduced IGD as a condition for further study Choo, H., Gentile, D., Sim, T., Li, D. D., Khoo, A., & Liau, A.

(APA, 2013) and suggested nine criteria for its diagnosis. (2010). Pathological video-gaming among Singaporean youth.

Using a psychometrically robust scale incorporating these Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore, 39(11), 822–829.

nine criteria, this study provided insight into the field of IGD Cleghorn, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Why do gamers buy

by examining a sample of Lebanese adolescents in relation to ‘virtual assets’? An insight in to the psychology behind

prevalence and potential predictors of IGD. Assessment using purchase behaviour. Digital Education Review, 27, 98–117.

the IGD-20 showed that the prevalence of IGD was 9.2% in Coakes, S. (2005). SPSS Version 14.0 for Windows: Analysis

the study’s population sample. Furthermore, the study iden- without anguish. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

tified some key predictors of IGD including being a younger Demirci, K., Akgönül, M., & Akpinar, A. (2015). Relationship of

adolescent, sleeping less, waking up from sleep more during smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and

the night to continue playing, and poor academic achieve- anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioral Addic-

ment. These empirical research findings suggest factors that tions, 4(2), 85–92. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.010

might guide early detection and prevention of IGD. Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., Ammannato, G., & Primi, C. (2015).

Versatility and addiction in gaming: The number of video-game

genres played is associated with pathological gaming in male

adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Network-

Funding sources: This research was supported by a grant ing, 18(2), 129–132. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0342

from the National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS) – Festl, R., Scharkow, M., & Quandt, T. (2013). Problematic com-

Lebanon (grant 3661/S). puter game use among adolescents, younger and older adults.

Addiction, 108(3), 592–599. doi:10.1111/add.12016

Authors’ contribution: NSH and MS contributed to the Fuster, H., Carbonell, X., Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016).

study concept and design. MS contributed to the collection Spanish validation of the Internet Gaming Disorder-20 (IGD-

of data and literature review. NSH contributed to the 20) Test. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 215–224.

interpretation of data and the statistical analysis and doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.050

obtained funding. MDG contributed to the supervision of Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a

the study, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4),

manuscript. 191–197. doi:10.1080/14659890500114359

Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Gaming addiction in adolescence (revisited).

Conflict of interest: No competing financial interests exist. Education and Health, 32(4), 125–129.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Pontes, H. (2016). A brief overview

of Internet gaming disorder and its treatment. Australian

Clinical Psychologist, 2(1), 20108.

REFERENCES Grüsser, S. M., Thalemann, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). Exces-

sive computer game playing: Evidence for addiction and

Achab, S., Nicolier, M., Mauny, F., Monnin, J., Trojak, B., Vandel, aggression? CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 290–292.

P., Sechter, D., Gorwood, P., & Haffen, E. (2011). Massively doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9956

multiplayer online role-playing games: Comparing character- Haghbin, M., Shaterian, F., Hosseinzadeh, D., & Griffiths, M. D.

istics of addict vs non-addict online recruited gamers in a (2013). A brief report on the relationship between self-control,

French adult population. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 144. video game addiction and academic achievement in normal and

doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-144 ADHD students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(4), 239–

American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and 243. doi:10.1556/JBA.2.2013.4.7

statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham,

American Psychiatric Association. R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper

Arora, T., Broglia, E., Thomas, G. N., & Taheri, S. (2014). Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Associations between specific technologies and adolescent Hawi, N. S. (2012). Internet addiction among adolescents in

sleep quantity, sleep quality, and parasomnias. Sleep Medicine, Lebanon. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 1044–

15(2), 240–247. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.799 1053. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.007

Bartel, K., & Gradisar, M. (2017). New directions in the link Hawi, N. S., & Rupert, M. S. (2015). Impact of e-Discipline

between technology use and sleep in young people sleep on children’s screen time. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and

disorders in children (pp. 69–80). New York, NY: Springer. Social Networking, 18(6), 337–342. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.

Brunborg, G. S., Mentzoni, R. A., & Frøyland, L. R. (2014). Is 0608

video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2016). To excel or not to excel: Strong

depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, evidence on the adverse effect of smartphone addiction on

or conduct problems? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(1), academic performance. Computers & Education, 98, 81–89.

27–32. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.002 doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.007

Brunborg, G. S., Mentzoni, R. A., Melkevik, O. R., Torsheim, T., Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017a). Relationships among smart-

Samdal, O., Hetland, J., Andreassen, C. S., & Palleson, S. phone addiction, anxiety, and family relations. Behaviour &

(2013). Gaming addiction, gaming engagement, and psycho- Information Technology, 36(10), 1046–1052. doi:10.1080/

logical health complaints among Norwegian adolescents. Media 0144929X.2017.1336254

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Hawi et al.

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017b). The relations among social Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Develop-

media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university ment and validation of a Game Addiction Scale for

students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), 576–586. Adolescents. Media Psychology, 12(1), 77–95. doi:10.1080/

doi:10.1177/0894439316660340 15213260802669458

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017c). Validation of the Arabic Lemos, I. L., Cardoso, A., & Sougey, E. B. (2016). Cross-cultural

version of the Internet Gaming Disorder-20 Test. Cyberpsy- adaptation and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the

chology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(4), 268–272. Brazilian version of the Video Game Addiction Test. Compu-

doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0493 ters in Human Behavior, 55, 207–213. doi:10.1016/j.

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Witt, E. A., Zhao, Y., & Fitzgerald, chb.2015.09.019

H. E. (2011). A longitudinal study of the effects of Internet use Lopez-Fernandez, O., Honrubia-Serrano, M. L., Baguley, T., &

and videogame playing on academic performance and the roles Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Pathological video game playing in

of gender, race and income in these relationships. Computers Spanish and British adolescents: Towards the exploration

in Human Behavior, 27(1), 228–239. doi:10.1016/j.chb. of Internet gaming disorder symptomatology. Computers in

2010.08.001 Human Behavior, 41, 304–312. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.011

Johansson, A., & Götestam, K. G. (2004). Problems with computer Müller, K., Janikian, M., Dreier, M., Wölfling, K., Beutel, M.,

games without monetary reward: Similarity to pathological Tzavara, C., Richardson, C., & Tsitsika, A. (2015). Regular

gambling. Psychological Reports, 95(2), 641–650. doi:10. gaming behavior and Internet gaming disorder in European

2466/pr0.95.2.641-650 adolescents: Results from a cross-national representative

Khazaal, Y., Chatton, A., Rothen, S., Achab, S., Thorens, G., survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological

Zullino, D., & Gmel, G. (2016). Psychometric properties of the correlates. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(5),

7-item Game Addiction Scale among French and German 565–574. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2

speaking adults. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 132. doi:10.1186/ Na, E., Choi, I., Lee, T. H., Lee, H., Rho, M. J., Cho, H., Jung,

s12888-016-0836-3 D. J., & Kim, D. J. (2017). The influence of game genre on

Kim, N. R., Hwang, S. S.-H., Choi, J.-S., Kim, D.-J., Demetrovics, Z., Internet gaming disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions,

Király, O., Nagygyörgy, K., Griffiths, M. D., Hyun, S. Y., 6(2), 248–255. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.033

Youn, H. C., &. Youn, H. C. (2016). Characteristics and psychi- Pápay, O., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M. D., Nagygyörgy, K., Farkas, J.,

atric symptoms of Internet gaming disorder among adults Kökönyei, G., Felvinczi, K., Oláh, A., Elekes, Z., &

using self-reported DSM-5 criteria. Psychiatry Investigation, Demetrovics, Z. (2013). Psychometric properties of the prob-

13(1), 58–66. doi:10.4306/pi.2016.13.1.58 lematic online gaming questionnaire short-form and prevalence

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Zwaans, T., & Kaptsis, D. (2013). of problematic online gaming in a national sample of adoles-

Clinical features and axis I comorbidity of Australian adoles- cents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking,

cent pathological Internet and video game users. Australian 16(5), 340–348. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0484

and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(11), 1058–1067. Petry, N. M., & O’Brien, C. P. (2013). Internet gaming disorder

doi:10.1177/0004867413491159 and the DSM‐5. Addiction, 108(7), 1186–1187. doi:10.1111/

Király, O., Nagygyörgy, K., Griffiths, M., & Demetrovics, Z. add.12162

(2014). Problematic online gaming. In K. Rosenberg & L. Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Portuguese validation of

Feder (Eds.), Behavioral addictions: Criteria, evidence and the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short form. Cyberpsychol-

treatment (pp. 61–95). New York, NY: Elsevier. ogy, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(4), 288–293.

Ko, C.-H. (2014). Internet gaming disorder. Current Addiction doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0605

Reports, 1(3), 177–185. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0030-y Pontes, H. M., Kiraly, O., Demetrovics, Z., & Griffiths, M. D.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Online gaming addiction in (2014). The conceptualisation and measurement of DSM-5

children and adolescents: A review of empirical research. Internet gaming disorder: The development of the IGD-20

Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1(1), 3–22. doi:10.1556/ Test. PLoS One, 9(10), e110137. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.

JBA.1.2012.1.1 0110137

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2017a). Chaos and Pontes, H. M., Macur, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Internet

confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet gaming disorder: gaming disorder among Slovenian primary schoolchildren:

Issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. Findings from a nationally representative sample of adoles-

Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 103–109. doi:10.1556/ cents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 304–310.

2006.5.2016.062 doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.042

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2017b). DSM-5 Rehbein, F., Kliem, S., Baier, D., Mößle, T., & Petry, N. M.

diagnosis of Internet gaming disorder: Some ways forward in (2015). Prevalence of Internet gaming disorder in German

overcoming issues and concerns in the gaming studies field. adolescents: Diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM‐5

Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 133–141. doi:10.1556/ criteria in a state‐wide representative sample. Addiction,

2006.6.2017.032 110(5), 842–851. doi:10.1111/add.12849

Lam, L. T. (2014). Internet gaming addiction, problematic use of the Rehbein, F., Staudt, A., Hanslmaier, M., & Kliem, S. (2016).

Internet, and sleep problems: A systematic review. Current Video game playing in the general adult population of

Psychiatry Reports, 16(4), 444. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0444-1 Germany: Can higher gaming time of males be explained by

Lemmens, J. S., & Hendriks, S. J. (2016). Addictive online games: gender specific genre preferences? Computers in Human

Examining the relationship between game genres and Internet Behavior, 55, 729–735. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.016

gaming disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Net- Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smart-

working, 19(4), 270–276. doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0415 phone addiction, stress, academic performance, and

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

IGD in Lebanon: Sleep and academic achievement

satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 321– gamers. Addiction, 106(1), 205–212. doi:10.1111/j.1360-

325. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045 0443.2010.03104.x

Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2017). Associations between Wang, C.-W., Chan, C. L., Mak, K.-K., Ho, S.-Y., Wong, P. W., &

screen media parenting practices and children’s screen time Ho, R. T. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of video and

in Lebanon. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 351–358. Internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents:

doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.06.002 A pilot study. The Scientific World Journal, 2014, 874648.

Sanders, J. L., & Williams, R. J. (2016). Reliability and validity of doi:10.1155/2014/874648

the Behavioral Addiction Measure for Video Gaming. Cyber- Wentworth, D. K., & Middleton, J. H. (2014). Technology use and

psychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(1), 43–48. academic performance. Computers & Education, 78, 306–311.

doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0390 doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.012

Satghare, P., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Chua, B. Y., Pang, S., Wittek, C. T., Finserås, T. R., Pallesen, S., Mentzoni, R. A., Hanss, D.,

Picco, L., Poon, L. Y., Chong, S. W., & Subramaniam, M. Griffiths, M. D., & Molde, H. (2015). Prevalence and

(2016). Prevalence of sleep problems among those with Inter- predictors of video game addiction: A study based on a national

net gaming disorder in Singapore. ASEAN Journal of Psychia- representative sample of gamers. International Journal of Mental

try, 17(1), 1–11. Health and Addiction, 14(5), 672–686. doi:10.1007/s11469-015-

Schmitt, Z. L., & Livingston, M. G. (2015). Video game addiction 9592-8

and college performance among males: Results from a 1 year Wu, A. M., Lai, M. H., Yu, S., Lau, J. T., & Lei, M.-W. (2016).

longitudinal study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire: Its psychometric

Networking, 18(1), 25–29. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0403 properties and correlation with Internet gaming disorder symp-

Spekman, M. L., Konijn, E. A., Roelofsma, P. H., & Griffiths, toms among Chinese people. Journal of Behavioral Addic-

M. D. (2013). Gaming addiction, definition and measurement: tions, 6(1), 11–20. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.007

A large-scale empirical study. Computers in Human Behavior, Yeh, D.-Y., & Cheng, C.-H. (2016). Relationships among

29(6), 2150–2155. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.015 Taiwanese children’s computer game use, academic achieve-

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Osterlind, S. J. (2001). Using ment and parental governing approach. Research in Education,

multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson. 95(1), 44–60. doi:10.7227/RIE.0025

Van Rooij, A. J., Schoenmakers, T. M., Vermulst, A. A., Van Den Young, K. (2009). Understanding online gaming addiction and

Eijnden, R. J., & Van De Mheen, D. (2011). Online video treatment issues for adolescents. American Journal of Family

game addiction: Identification of addicted adolescent Therapy, 37(5), 355–372. doi:10.1080/01926180902942191

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

You might also like

- Lopez-Fernandez CHB 2014Document9 pagesLopez-Fernandez CHB 2014Renato BenigayNo ratings yet

- Effects of Online Games On The Personality of Adolescents: Simran KaurDocument6 pagesEffects of Online Games On The Personality of Adolescents: Simran KaurfitriyahNo ratings yet

- Is Video Gaming, or Video Game Addiction, Associated With Depression, Academic Achievement, Heavy Episodic Drinking, or Conduct Problems?Document6 pagesIs Video Gaming, or Video Game Addiction, Associated With Depression, Academic Achievement, Heavy Episodic Drinking, or Conduct Problems?Radael JuniorNo ratings yet

- Spanish Validation and Scoring of The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale - Short-Form (IGDS9-SF)Document11 pagesSpanish Validation and Scoring of The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale - Short-Form (IGDS9-SF)Pilar Martínez SánchezNo ratings yet

- Perceived Problems With Adolescent Online Gaming: National Differences and Correlations With Substance UseDocument14 pagesPerceived Problems With Adolescent Online Gaming: National Differences and Correlations With Substance UseNikki Diocson Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Jba 07 03 75Document12 pagesJba 07 03 75weltor26No ratings yet

- Family Media and School Related Risk FacDocument11 pagesFamily Media and School Related Risk FacNicoló DelpinoNo ratings yet

- La Eficacia de Una Guía para Padres para La Prevención de VideojuegosDocument10 pagesLa Eficacia de Una Guía para Padres para La Prevención de VideojuegosItahisa JimenezNo ratings yet

- Mobile Gaming and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Comparative Study Between Belgium and FinlandDocument10 pagesMobile Gaming and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Comparative Study Between Belgium and FinlandLea BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Pan 2020Document11 pagesPan 2020Vanessa AldeaNo ratings yet

- Molde2019 Article AreVideoGamesAGatewayToGamblinDocument13 pagesMolde2019 Article AreVideoGamesAGatewayToGamblinunproudly 8No ratings yet

- 10 22492 Ijpbs 6 1 06 PDFDocument16 pages10 22492 Ijpbs 6 1 06 PDFRyla JimenezNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Video Gaming, Gambling, and Problematic Levels of Video Gaming and GamblingDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between Video Gaming, Gambling, and Problematic Levels of Video Gaming and Gamblingunproudly 8No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0747563219303425 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0747563219303425 MainSAFWA BATOOL NAQVINo ratings yet

- Internet Gaming Disorder An Emerging Addiction Among Pakistani University StudentsDocument18 pagesInternet Gaming Disorder An Emerging Addiction Among Pakistani University Studentsshimama kanwalNo ratings yet

- Video Gaming and Children's Psychosocial Wellbeing: A Longitudinal StudyDocument14 pagesVideo Gaming and Children's Psychosocial Wellbeing: A Longitudinal StudyGiovani Gil Paulino VieiraNo ratings yet

- Performance Enhancing Drug in Video GameDocument7 pagesPerformance Enhancing Drug in Video Gamejerry vanlinNo ratings yet

- Practical Research Softcopy Final G10Document70 pagesPractical Research Softcopy Final G10kyla santosNo ratings yet

- Şalvarlı-Griffiths2019 Article InternetGamingDisorderAndItsAsDocument23 pagesŞalvarlı-Griffiths2019 Article InternetGamingDisorderAndItsAsManuela Martín-Bejarano GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: A B C D D eDocument6 pagesPsychiatry Research: A B C D D eCem AltıparmakNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: Computers & EducationDocument15 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Computers & EducationvogonsoupNo ratings yet

- Estudio 1. Lau Et Al. 2018Document16 pagesEstudio 1. Lau Et Al. 2018Patricia Loza MartínezNo ratings yet

- 2006 Article p601Document10 pages2006 Article p601husnainNo ratings yet

- IGD and ADHDDocument28 pagesIGD and ADHDJefferson CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Effects of Excessive Screen Time On Neurodevelopment, Learning, Memory, Mental Health, and Neurodegeneration: A Scoping ReviewDocument21 pagesEffects of Excessive Screen Time On Neurodevelopment, Learning, Memory, Mental Health, and Neurodegeneration: A Scoping ReviewDavid García-Ramos GallegoNo ratings yet

- Kecanduan Video Game Dan Tekanan Psikologis Di Kalangan EkspatriatDocument6 pagesKecanduan Video Game Dan Tekanan Psikologis Di Kalangan EkspatriatKukuh Aji25No ratings yet

- Sakuma 2016Document6 pagesSakuma 2016Julián Alberto MatulevichNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Addiction To Online Video Games GamiDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Addiction To Online Video Games Gamijake lipovetskyNo ratings yet

- Gaming Disorder1)Document8 pagesGaming Disorder1)MARCIO RENATO MARQUES GAERTNERNo ratings yet

- The Problem & Its BackgroundDocument8 pagesThe Problem & Its Backgroundjhonpaulquiring25No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 Pa OiDocument13 pagesCHAPTER 2 Pa OiMervinlloyd Allawan BayhonNo ratings yet

- Online For Most AdolescentsDocument10 pagesOnline For Most AdolescentsKhadija ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- Factorial Invariance & Network Structure of The GAD7 - PreprintDocument42 pagesFactorial Invariance & Network Structure of The GAD7 - PreprintDOREN TRICIA CUNANANNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Abrep 2020 100307Document26 pages10 1016@j Abrep 2020 100307indrayeniNo ratings yet

- Chapter II)Document5 pagesChapter II)Gian MonesNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesLiterature ReviewYasir AhmedNo ratings yet

- 254-Article Text-1155-2-10-20230930-1Document6 pages254-Article Text-1155-2-10-20230930-1castrocheska046No ratings yet

- Ayar N BektasDocument8 pagesAyar N Bektasduwit qtNo ratings yet

- NextDocument21 pagesNextLeo Fernandez Tipayan Galan IINo ratings yet

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Video GamesDocument8 pagesAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Video GamesLissa WanderleyNo ratings yet

- s11469 022 00890 2Document18 pagess11469 022 00890 2故时吟安No ratings yet

- Assignment 4Document10 pagesAssignment 4sherinNo ratings yet

- Estudio 3. Rehbein Et Al. 2010Document11 pagesEstudio 3. Rehbein Et Al. 2010Patricia Loza MartínezNo ratings yet

- Videogame-Related Experiences Among Regular Adolescent GamersDocument17 pagesVideogame-Related Experiences Among Regular Adolescent Gamerszarbitt52No ratings yet

- Mina TayDocument20 pagesMina TayHayam Salic BocoNo ratings yet

- Medicina 56 00221 v2Document15 pagesMedicina 56 00221 v2jcarrionravinesNo ratings yet

- Igd Post PrintDocument22 pagesIgd Post PrintVito RizzoNo ratings yet

- Research Article No.2Document6 pagesResearch Article No.2Elle EnolbaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Video Game Functional Assessment-Revised (VGFA-R) and Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGD-20)Document7 pagesComparison of The Video Game Functional Assessment-Revised (VGFA-R) and Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGD-20)Claire TiersenNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Gaming Disorder in Children and Adolescents - A School-Based StudyDocument4 pagesPredictors of Gaming Disorder in Children and Adolescents - A School-Based StudyEdmar SilvaNo ratings yet

- "The Effects of Online Games in The Academic Performance of Grade 11 Students in Green Fields Integrated School of Laguna" (Group 5)Document13 pages"The Effects of Online Games in The Academic Performance of Grade 11 Students in Green Fields Integrated School of Laguna" (Group 5)Mark Angelo Zaspa100% (1)

- Attention Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder and Video Games: A Comparative Study of Hyperactive and Control ChildrenDocument8 pagesAttention Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder and Video Games: A Comparative Study of Hyperactive and Control ChildrenpriyaNo ratings yet

- HBM 39 4471Document9 pagesHBM 39 4471Pedro Henrique Ramos De SouzaNo ratings yet

- GRP 4 Final Manuscirpt Stem FDocument19 pagesGRP 4 Final Manuscirpt Stem FTASHA KATE REYESNo ratings yet

- Video Games and AutismDocument14 pagesVideo Games and AutismEla AndreicaNo ratings yet

- Game Addiction ArticleDocument10 pagesGame Addiction ArticleRonaldas GadzimugometovasNo ratings yet

- GriffithsDocument39 pagesGriffithsMurandari DjequelineNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- Internet Addiction in Adolescents: The PROTECT Program for Evidence-Based Prevention and TreatmentFrom EverandInternet Addiction in Adolescents: The PROTECT Program for Evidence-Based Prevention and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- The Phobia of the Modern World: Nomophobia: "Conceptualization of Nomophobia and Investigation of Associated Psychological Constructs"From EverandThe Phobia of the Modern World: Nomophobia: "Conceptualization of Nomophobia and Investigation of Associated Psychological Constructs"No ratings yet

- Rozdział 12 Słownictwo Grupa BDocument1 pageRozdział 12 Słownictwo Grupa BBartas YTNo ratings yet

- Bylaws-Craigs Mill Hoa 2013Document10 pagesBylaws-Craigs Mill Hoa 2013api-243024250No ratings yet

- Department of Civil Engineering Uttara University: LaboratoryDocument102 pagesDepartment of Civil Engineering Uttara University: LaboratorytaniaNo ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument2 pagesSyllabusPrakash KumarNo ratings yet

- SRP (305 320) 6MB - MX - enDocument2 pagesSRP (305 320) 6MB - MX - enShamli AmirNo ratings yet

- CyberPunk 2020 - Unofficial - Reference Book - Ammo and Add-OnsDocument6 pagesCyberPunk 2020 - Unofficial - Reference Book - Ammo and Add-Onsllokuniyahooes100% (1)

- Benefits of SwimmingDocument3 pagesBenefits of Swimmingaybi pearlNo ratings yet

- Allosteric Regulation & Covalent ModificationDocument10 pagesAllosteric Regulation & Covalent ModificationBhaskar Ganguly100% (1)

- Internship-Plan BSBA FInalDocument2 pagesInternship-Plan BSBA FInalMark Altre100% (1)

- Labor To DigestDocument32 pagesLabor To Digestphoenix rogueNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Lesson 1 Chlor-Alkali IndustryDocument16 pagesUnit 2 Lesson 1 Chlor-Alkali IndustryGreen JeskNo ratings yet

- Mineral Resources, Uses and Impact of MiningDocument4 pagesMineral Resources, Uses and Impact of MiningShakti PandaNo ratings yet

- A Rare Peripheral Odontogenic Keratocyst in Floor of Mouth: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesA Rare Peripheral Odontogenic Keratocyst in Floor of Mouth: A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Paper - Impact of Rapid Urbanization On Agricultural LandsDocument10 pagesPaper - Impact of Rapid Urbanization On Agricultural LandsKosar Jabeen100% (1)

- First Quarter Examination For AP 10Document4 pagesFirst Quarter Examination For AP 10Reynan Orillos HorohoroNo ratings yet

- 1501Document569 pages1501Ina Revenco33% (3)

- Slender Quest DetailsDocument1 pageSlender Quest Detailsparents021No ratings yet

- The Three Modern Relationship Models and Why They Are All FlawedDocument5 pagesThe Three Modern Relationship Models and Why They Are All FlawedBingoNo ratings yet

- Natural Medicine - 2016 October PDFDocument100 pagesNatural Medicine - 2016 October PDFDinh Ta HoangNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Seat Puller KitDocument2 pagesHydraulic Seat Puller KitPurwanto ritzaNo ratings yet

- The Internet Test 9th Grade A2b1 Tests 105573Document5 pagesThe Internet Test 9th Grade A2b1 Tests 105573Daniil CozmicNo ratings yet

- Memorandum - World Safety Day "2023''Document2 pagesMemorandum - World Safety Day "2023''attaullaNo ratings yet

- IDSA Guias Infeccion de Tejidos Blandos 2014 PDFDocument43 pagesIDSA Guias Infeccion de Tejidos Blandos 2014 PDFyonaNo ratings yet

- Octavia Tour BrochureDocument9 pagesOctavia Tour BrochureOvidiuIONo ratings yet

- Grammar Practice English Vi Second PartDocument8 pagesGrammar Practice English Vi Second PartBrando Olaya JuarezNo ratings yet

- Sample Cylinders - PGI-CYLDocument8 pagesSample Cylinders - PGI-CYLcalpeeNo ratings yet

- IR Beam LaunchingDocument2 pagesIR Beam LaunchingalfredoNo ratings yet

- SECTION 03310-1 Portland Cement Rev 1Document10 pagesSECTION 03310-1 Portland Cement Rev 1Abdalrahman AntariNo ratings yet

- Physical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human HealthDocument24 pagesPhysical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human Health0395No ratings yet

- Microcosmic Orbit Breath Awareness and Meditation Process: For Enhanced Reproductive Health, An Ancient Taoist MeditationDocument1 pageMicrocosmic Orbit Breath Awareness and Meditation Process: For Enhanced Reproductive Health, An Ancient Taoist MeditationSaimon S.M.No ratings yet