Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Tribute To Fela: Wole Soyinka, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2007)

A Tribute To Fela: Wole Soyinka, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2007)

Uploaded by

Sergio FernandesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Tribute To Fela: Wole Soyinka, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2007)

A Tribute To Fela: Wole Soyinka, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2007)

Uploaded by

Sergio FernandesCopyright:

Available Formats

A tribute to Fela

The news came on my portable radio and it sounded so strange, a floating

contradiction that was at once detached from, yet, infused with the world from which

I had myself just earned a lover’s rebuff. My young cousin, the abàmi èdà that the

world knew as Fela, was dead. He had not yet attained his sixtieth year.

A naked torso over spangled pants, over which a saxophone or microphone would

oscillate on stage, receiving guests or journalists in underpants while running down a

tune from his head, in the open courtyard at rehearsals or in any space where he held

court – all constituted the trademark of his unyielding non-conformism. (…)

Fela loved to buck the system. His music, to many, was both salvation and echo of

their anguish, frustrations and suppressed aggression. The black race was the

beginning and end of knowledge and wisdom, his life mission, to effect a mental and

physical liberation of the race.

[In 1984] I had travelled to Paris in order to campaign for Fela’s freedom at a

mammoth music concert under yet another dictatorship, that of General Buhari’s

government had flung him in prison on spurious charges of currency offence. Under

the general anti-racism and human rights slogan – Touche pas à mon pote (Don’t

touch my mate!) - the organisers of the concert planned to devote a special spot to

publicise Fela’s unjust imprisonment and mobilise world opinion on his behalf.

On the day of Fela’s funeral, the whole of Lagos stood still, all businesses were

suspended and any governmental presence banished. The mammoth crowd at the

funeral of this most vocal and unrelenting dissident being was, firstly, a tribute to his

person. Following this however, it was also a statement of defiance to the regime of

Sani Abacha. (…) Fela’s funeral was thus an occasion that the people exploited to the

full, pouring out in a way that defied the regime’s ban on public gatherings, making

the Black President the mouthpiece of their repressed feelings, even in his lifeless

form. Neither the police nor the military dared show its face on that day, and the

uniformed exceptions only came to pay tribute.

Wole Soyinka, You Must Set Forth At Dawn (2007)

You might also like

- Lindy Hop EssayDocument5 pagesLindy Hop EssayffbugbuggerNo ratings yet

- My Children My Africa IntroDocument12 pagesMy Children My Africa Introsaeed33% (3)

- Amin Maalouf - Disordered World - Setting A New Course For The Twenty-First Century PDFDocument176 pagesAmin Maalouf - Disordered World - Setting A New Course For The Twenty-First Century PDFbuildingma5243No ratings yet

- BIKO 1bDocument25 pagesBIKO 1bnsovosambo100% (3)

- Wole Soyinka's "A Dance of The Forests" The Fourth Stage Tragedy.Document18 pagesWole Soyinka's "A Dance of The Forests" The Fourth Stage Tragedy.Zahra Gaad100% (4)

- The Contribution of Frantz Fanon To The Process of The Liberation of The People by Mireille Fanon-Mendès France PDFDocument6 pagesThe Contribution of Frantz Fanon To The Process of The Liberation of The People by Mireille Fanon-Mendès France PDFTernassNo ratings yet

- Pop Grenade: From Public Enemy to Pussy Riot - Dispatches from Musical FrontlinesFrom EverandPop Grenade: From Public Enemy to Pussy Riot - Dispatches from Musical FrontlinesNo ratings yet

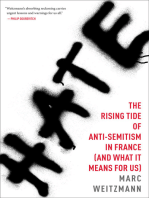

- Hate: The Rising Tide of Anti-Semitism in France (and What It Means for Us)From EverandHate: The Rising Tide of Anti-Semitism in France (and What It Means for Us)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- "The Bench by Richard Rive": Literary CriticismDocument2 pages"The Bench by Richard Rive": Literary CriticismAljhun AbellaNo ratings yet

- What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and ThoughtFrom EverandWhat Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Addictive Ideologies: Finding Meaning and Agency When Politics Fail YouFrom EverandAddictive Ideologies: Finding Meaning and Agency When Politics Fail YouNo ratings yet

- Frantz Fanon in the United States, Followed by Comments from His Wife, Josie FanonFrom EverandFrantz Fanon in the United States, Followed by Comments from His Wife, Josie FanonNo ratings yet

- Finding Fela: My Strange Journey to Meet the AfroBeat King in Lagos [1983]From EverandFinding Fela: My Strange Journey to Meet the AfroBeat King in Lagos [1983]Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- On The Contrary: Leading The Opposition In A Democratic South AfricaFrom EverandOn The Contrary: Leading The Opposition In A Democratic South AfricaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Other Side of History: An anecdotal reflection on political transition in South AfricaFrom EverandThe Other Side of History: An anecdotal reflection on political transition in South AfricaNo ratings yet

- Gaddafi's Harem: The Story of a Young Woman and the Abuses of Power in LibyaFrom EverandGaddafi's Harem: The Story of a Young Woman and the Abuses of Power in LibyaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (23)

- Fela Anikulapo-Kutis Beast of No NationDocument16 pagesFela Anikulapo-Kutis Beast of No NationAMAN kills47No ratings yet

- Role of Music in ApartheidDocument17 pagesRole of Music in ApartheidTa XiNo ratings yet

- South Africa: His Ory O Oppress On and S Rugg: T F I T LEDocument19 pagesSouth Africa: His Ory O Oppress On and S Rugg: T F I T LEkemalNo ratings yet

- "After Mandela: The Struggle For Freedom in Post-Apartheid South Africa" by Douglas FosterDocument10 pages"After Mandela: The Struggle For Freedom in Post-Apartheid South Africa" by Douglas FosterOnPointRadioNo ratings yet

- Tran Late of Sorrow Tears and BloodDocument6 pagesTran Late of Sorrow Tears and BloodMario Anikulapo BritoNo ratings yet

- Liberation of Southern Africa, Our Responsibility: Selected Speeches of Olof PalmeDocument78 pagesLiberation of Southern Africa, Our Responsibility: Selected Speeches of Olof PalmeEnuga S. ReddyNo ratings yet

- Singing The Mozambican Struggle For National LiberationDocument44 pagesSinging The Mozambican Struggle For National LiberationLisboa24No ratings yet

- Panday Sunitha 2004Document95 pagesPanday Sunitha 2004Jacky van der HeideNo ratings yet

- Frantz Fanon and His Blueprint For African Culture(s) - Apeike Umolu - AfricxnDocument12 pagesFrantz Fanon and His Blueprint For African Culture(s) - Apeike Umolu - AfricxnApeike UmoluNo ratings yet

- Drewett 2005 Stop This FilthDocument18 pagesDrewett 2005 Stop This FilthMorneBezuidenhoutNo ratings yet

- En122 Fanon-2018Document17 pagesEn122 Fanon-2018typaldaki78No ratings yet

- "Go Dad!": A Discussion On Johnny Clegg and Ethnographic Show BusinessDocument11 pages"Go Dad!": A Discussion On Johnny Clegg and Ethnographic Show BusinessPhilip BrosterNo ratings yet

- Unit 4Document11 pagesUnit 4Ainhoa G. GilNo ratings yet

- A Newer Darkness Time: March 23, 1974, Buenos Aires, ArgentinaDocument5 pagesA Newer Darkness Time: March 23, 1974, Buenos Aires, ArgentinaAthanasios GalanisNo ratings yet

- The Role of Reggae Music The African Liberation Struggle PaperDocument5 pagesThe Role of Reggae Music The African Liberation Struggle PaperSharon OkothNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Excerpt: 'Ruth First and Joe Slovo in The War Against Apartheid' (Monthly Review Press)Document8 pagesExclusive Excerpt: 'Ruth First and Joe Slovo in The War Against Apartheid' (Monthly Review Press)Terry Townsend, EditorNo ratings yet

- Fouche BiographyDocument16 pagesFouche BiographyEvan BourassaNo ratings yet

- 202004120632194318nishi Dance of The Forests 9Document15 pages202004120632194318nishi Dance of The Forests 9Fajer TanveerNo ratings yet

- Analysis of A Walk in The Night by AlexDocument15 pagesAnalysis of A Walk in The Night by Alexngakwen loic100% (1)

- Henderson1996 PDFDocument32 pagesHenderson1996 PDFHarold ColonNo ratings yet

- Baraka Blues AestheticDocument9 pagesBaraka Blues AestheticRaw SasigNo ratings yet

- Eli Johnson - Persuasive EssayDocument3 pagesEli Johnson - Persuasive Essayapi-586507751No ratings yet

- Why Mandela Festival UploadDocument69 pagesWhy Mandela Festival UploadAlizona Theostell59No ratings yet

- The Grand (Hip Hop) Chessboard by Hishaam AidiDocument15 pagesThe Grand (Hip Hop) Chessboard by Hishaam AidiBunmi OloruntobaNo ratings yet

- Ik Mar 78Document84 pagesIk Mar 78Phila DoloNo ratings yet

- Nsukka Journal of The Humanities, Number 14, CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE THE PURPLE HIBISCUS - AN ALLEGORICAL STORY OF MAN STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOMDocument24 pagesNsukka Journal of The Humanities, Number 14, CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE THE PURPLE HIBISCUS - AN ALLEGORICAL STORY OF MAN STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOMAlex WasabiNo ratings yet

- Nostalgic Waves from Soweto: Poetic Memories of the June 16th UprisingFrom EverandNostalgic Waves from Soweto: Poetic Memories of the June 16th UprisingNo ratings yet

- A Water A: To The Cultural Universa TureDocument48 pagesA Water A: To The Cultural Universa TurekermitNo ratings yet

- 68IJELS 101202035 TheMyth PDFDocument13 pages68IJELS 101202035 TheMyth PDFIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- CHERKI, Alice - Frantz Fanon - A PortraitDocument276 pagesCHERKI, Alice - Frantz Fanon - A Portraitsofiia.hataullinaNo ratings yet

- Dario FoDocument13 pagesDario FoRidhi SahaniNo ratings yet

- The Generation of Modern African Playwrights in Southern Africa PDFDocument11 pagesThe Generation of Modern African Playwrights in Southern Africa PDFMaahes Cultural LibraryNo ratings yet

![Finding Fela: My Strange Journey to Meet the AfroBeat King in Lagos [1983]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/193674470/149x198/293f083c9e/1676596473?v=1)