Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Simon Lightfoot

Simon Lightfoot

Uploaded by

Creepy BarbieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Simon Lightfoot

Simon Lightfoot

Uploaded by

Creepy BarbieCopyright:

Available Formats

Pol-casting: The use of Podcasting in the teaching and learning of

Politics and International Relations

Jason Ralph, Naomi Head, Simon Lightfoot

School of Politics and International Studies

University of Leeds

Esther Jubb, School of Social Science, Liverpool John Moores University

Paper to be presented at the Higher Education Academy Annual

Conference, 1-3 July 2008

This project is funded by C-SAP Tranche 7 Funding. Their

support is acknowledged with thanks.

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 1

Podcasting offers a novel mechanism for delivering teaching materials and

facilitating learning (see Swain, 2006). The term ‘Podcasts’ is derived

from ‘iPod’ (which is the portable multimedia player from Apple) and

‘broadcast’ (Lim, 2006). Podcasting involves audio files on the Internet in

conjunction with an RSS FEED that automatically downloads files over

time. The explosion in the availability of podcasts has meant that material

that is relevant to learning and teaching in Politics and International

Relations is increasingly available. Alongside this the technology offers

new and innovative teaching and learning methods to transform the

student experience.

This paper summarises the findings of a research project that explores the

use of podcasts in the learning and teaching of Politics and International

Relations. It highlights within a strategy of blended learning on campus,

what added value can the consumption and production of podcasts bring

to the learning process? It also aims to go some way towards identifying

the ‘perfect blend’ of podcasting and traditional methods which can

support student learning of Politics and International Relations in the 21 st

century media rich environment.

The paper has three main sections. The first explore some of the

pedagogic issues associated with the use of podcasts. The second

highlights issues to consider, before outlining examples of good practice

for using podcast material in lectures/seminars. Finally, and perhaps most

importantly, it outlines student attitudes to the use of podcasts within

learning and teaching. In particular, it will reflect upon whether students

perceived podcasts as a substitute to traditional learning activities or as

complementary, points that are applicable to all aspects of e-learning.

Pedagogic Debate

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 2

The current pedagogic research that exists (Beldarrain, 2006; Campbell,

2005; Huann & Thong, 2006; the IMPALA project 1) highlights several

potential benefits and drawbacks with the use of podcasting. The first is

that it appeals to current students, who are often seen as digital natives

(Prensky, 2001). Podcasts can also map onto the chronological nature of

typical HE teaching. The majority of courses are structured on a weekly

basis with a different learning activity planned each week. Podcasts clearly

overcome to issue associated with traditional lectures is that you only get

one chance to hear it. If you learn best via listening rather than reading

this creates problems. You can re-read a text until you understand it. That

option is not open to auditory learners. Podcasting lectures or seminars

gives these students a choice about where and when to access digital

material and how many times they wish to repeat it (Knight 2006). As

Gribbins argues ‘Recorded lectures distributed via podcast can allow

students to “re-attend” class’ (Gribbins, 2007). Podcasts therefore allow

students to listen to audio material in a wide variety of contexts and

ensure full understanding of the class (Chinnery, 2006; Knight, 2006).

Other benefits include allowing students flexible access to teaching

materials and adding variety to the learning experience.

The pedagogic issues associated with podcasting include the fact that not

all students will have access or be familiar with the technology, students

with some disabilities will have difficulty using podcasts, and listening to

podcasts could be a passive learning activity (see SDDU 2007). There is

also the question of attendance at lectures. The availability of full lecture

podcasts could contribute to a decline in class attendance, resulting in

students failing to build up relations with their tutors or peers. They could

also fail to learn crucial skills such as note taking. Supporters of podcasts

argue that ‘students are more likely to go to class and participate in the

conversation because they are not worried about writing everything down’

(in Knight, 2006). Studies from other schools at Leeds have shown that

engaging with students in a dialogue about podcasts and attendance

produced no discernibly large drop in attendance.

1

The Informal Mobile Podcasting And Learning Adaptation (IMPALA) project investigates the impact of

Podcasting on student learning and how the beneficial effects can positively be enhanced.

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 3

One major argument is that some of these issues are not necessarily a

consequence of technology and e-learning. Podcasting is merely a means

of delivering teaching material, it does not dictate the nature of that

material or its educational value. However, once the pedagogic issues

have been dealt with there are also practical questions of resources and

copyright that need to be considered by staff. In the second section, the

paper will therefore briefly illustrate some top tips for using podcasts.

Issues to note

As with the use of any technology there are a number of issues that need

to be considered.

Podcasting or Audio?

A common misperception of podcasting is that it is simply the provision of

audio files which can be downloaded by students for use at their own

convenience. Although a perfectly valid teaching tool, this is not in fact

podcasting. Podcasting requires the use of an RSS feed – a Really Simple

Syndication feed for those who like jargon! What it does is to ‘push’ the

audio files out to the students once they have added the RSS feed (usually

taken from the web address) to any aggregator such as iTunes. Every time

you upload a new file, it appears on their iTunes the next time they open it

up. Our data shows that almost unanimously, students like the fact that

material can be delivered to them in such a way. While this raises valid

pedagogic questions concerning research skills, it does offer innovative

ways of communicating with students.

Equipment

The equipment needed for podcasting is, by and large, fairly simple to

purchase and to use: a good quality digital voice recorder, a pair of

headphones, editing software such as Audacity which is free to download

from the internet, and perhaps audio conversion software which allows you

to convert audio files to different formats. Again, this software is easy to

install and to navigate. It is worth speaking to university technical and e-

learning staff to ensure that there is server space available for uploading

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 4

and storing large quantities of audio and video material. Similarly, it is

time well spent ensuring that you have sufficient space available on

personal office computers. We recorded one lecture which was 71 MB!

This made the file very difficult to store and reduced its portability. We

were able to reduce the file size but at greatly reduced quality, almost to

the point of inaudibility. For these massive files we ended up digitally

streaming them, which is clearly not podcasting but our view was that

accessibility for students was the main criteria. There are a number of

web-based aggregators available, as well as the more well-known iTunes

software. If your university does not make iTunes available to students,

then you may have to look at other aggregators or investigate whether the

University Virtual Learning Environment can do this. Our experiences

suggested that such projects are perhaps ahead of the game and that

there needs to be University – level strategies for the purchasing of

equipment for staff and student use, audio-visual software support and

server use.

Our uses of podcasts

Lim categorises the current practice of using podcasts as either

‘consumption’ (i.e. using podcasts that are already ‘out there’ on the

internet) or ‘production’ (Lim, 2006). This project examined both aspects

via four trials at the University of Leeds:

Opening student access to new learning materials via commercial

podcasts that they can subscribe to, such as US election podcasts.

Using a social bookmarking website to host relevant podcasts and

allowing students to add new contributions to the site, building a

pod library or listening list.

Staff producing weekly podcasts summarising the lecture, specific

topics or revision guides

Asking students to create their own podcasts

Our initial idea was to create a pod library, but copyright laws prevent the

uploading of material downloaded from another source. Our solution was

to use a social bookmarking site grazr. Social bookmarking allows those

interested in a particular topic to in effect create a link to a relevant site

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 5

which like-minded individuals can follow. Our podlibrary, in other words, is

a collection of links to websites that host podcasts rather than a collection

of files that have been downloaded and then uploaded again. In addition,

the social bookmarking site potentially allows us to create a ‘community of

practice’ whereby we can share information with other users, which

includes other users posting relevant files.

On the production side we created “podules” as an enhancement means

of communication. Podules are small files that are produced by the project

to summarise the key point of the lecture, highlight a particular issue or

act as a guide to further reading or listening. These were produced weekly

and therefore were able to be set up for an RSS feed. This follows the

model of ‘Profcasting’ trialled by the IMPALA project (Edirisingha &Salmon,

2007) and the model employed at the University of Sydney (see Clark,

Taylor & Westcott, 2007). We also asked students to produce their own

podcast summaries of the seminar discussion. This mirrors work elsewhere

which has produced favourable feedback (see Lee et al, 2008). Asking

students to summarise seminars can be seen as them participating in their

own learning or active learning. Indeed Lee et al argue that the true

potential of podcasting technology lies in its knowledge-creation value,

and its use as a vehicle for disseminating learner-generated content (Lee

et al, 2008, p. 504). There was also one full lecture recorded and made

available via a blog (we created a blog to try and overcome space issues).

Findings

Our initial findings gathered through student focus groups and surveys

indicated a number of useful conclusions:

There was an appreciation of the additional flexibility but a rejection of

the idea of the podcast as a substitute for traditional contact time.

Students welcomed a range of learning resources particularly if they

reiterated points that had been stressed in the lecture.

“I think it [a podcast] would be good because sometimes if the

lecture goes too fast you can’t actually take down the main

point, so if you can pause it and play it whenever you want to

then you can kind of note down the points at your own pace.”

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 6

Students had a variety of learning styles but did not see podcasting as

a replacement for traditional learning methods.

If downloadable audio files (MP3 files and podcasts) were available to

support your studies, when would you most likely use these educational

materials? Please only choose one option.

In place of

6.9% 6

attending lectures:

As a way to

reinforce or review

what has been 60.9% 53

discussed in a

lecture:

As a revision aid

31.0% 27

before exams:

Not at all: 1.1% 1

“I quite like going to lectures. I like listening to people. I like

going to seminars as well. I like talking to people and

interacting with people. Actually I like getting a broad range

of resources. It makes it more interesting if you’ve got a

range of stuff to go to.”

“It depends on how it is used as a learning resource. I think

it’s quite a good idea as an additional learning resources if it’s

going to be a brief summary of what’s already happened. But

it is difficult because if they were going to be half an hour or

an hour then it could replace the lecture or make the lectures

pointless...but as a brief summary of what’s already happened

I think that’s a great idea.”

Students thought podcasts could be made part of a structured learning

process and in fact this was preferable rather than an addition to the

normal processes. Otherwise students would find it too easy to ignore.

This was true of the pod library experience-student use was limited

“It depends if it’s made a part of learning process as well. If it

is left as an additional resource then you have an option to

use it or not, then people won’t make it part of their habits.

But if in every seminar there’s a reference to last week’s

podcast ... then everyone would use it. But if it’s unnecessary

then I don’t think people will use it.”

Students expressed some doubts about whether they would listen to

other student’s podcasts. However there was enthusiasm for learning

about the process of making podcasts and integrating it more

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 7

substantially into an assessment strategy. They were also in favour of

the lecturer’s ‘podule’.

‘for getting information, the lecturer’s podcast would be more

appealing, but the student one for me anyway would be – not

fun to listen to – but something different, to see what other

opinions are in other seminar groups’.

‘...even if they [student podcasts] are not as coherent or

knowledgeable, it would still be useful because you can draw

other ideas from what people are saying.’

‘...it’s part of growing up and learning new skills at University.

Particularly because podcasts now are so widely used.’

Students who had produced the initial podcasts were already reflecting

on the different kind of presentation skills they had developed and the

benefits of these.

Students believed that the task of producing a podcast would force

them to concentrate on taking traditional skills such as note taking,

writing and presentation skills to a different level. Time, however was

an issue.

“I don’t know if I would listen to it in my bedroom when I’m

revising. I think I would listen to it for example on the way

into uni or into town..so I can kill two birds with one stone.”

“There’s plenty of time to kill on the bus... time’s not an

excuse not to listen particularly to a 5 minute summary”.

“I think it’s another useful resource but I don’t think I would

replace what I already do with that.’

There were a number of technical problems that affected the project.

Whilst the creation of the pod library was a success it did not work quite

how we intended it. In part this was due to technological problems that

limited uploading rights to the member of the project team that created

the site. The other issue was how to handle large audio files. Our solution

was to create a module blog. This was created successfully but the fact

that students had to go to one site for powerpoint slides (the University

‘Portal’), the blog for produced audio files as well as the social

bookmarking site to consume podcasts was not user friendly.

Conclusions

The above are the findings of the use of podcasts in one module at one

university. However, they appear to replicate findings from other studies in

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 8

the UK, USA and Australia. Our podcasting experience has met with a

variety of reactions among students and staff, overall, it must be said,

positive reactions. We have identified genuine benefits and concerns as

voiced by students relating to the addition of podcasting to the range of

methods currently used in academic teaching. These need to be taken

seriously, but they do not rule out its further use as a learning and

teaching tool. We are conscious of the fact, however, that the present

project is running alongside a module and in this respect students see it as

something in addition to, rather than as an integral part of, their

education. This has tended to put some students off fully engaging with

the project, particularly those third year students who tend to look at this

part of their degree rather instrumentally. What we have discovered,

however, is that it is both possible and desirable to take the next step and

think of ways of integrating the practice of producing podcasts into the

learning methods and objectives of PIR modules. Lee et al argue that

podcasting allows ‘students to articulate their understanding of ideas and

concepts, and to share the outcomes with an audience they value, such as

their peers’ (Lee et al, 2008, p. 518). We concur with this argument,

believing that the student act of producing podcasts can concentrate

student mind on refining presentation and broader academic skills as well

as enhancing their general learning experience

References

Beldarrain, Y (2006), 'Distance Education Trends: Integrating new

technologies to foster student interaction and collaboration', Distance

Education, 27: 2, 139 - 153

Campbell, G (2005) ‘There is something in the air: Podcasting in Education’

EDUCAUSE Review 40: 6.

Chinnery, G (2006) EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

Going to the MALL: Mobile Assisted Language Learning, Language

Learning & Technology, Vol. 10, No. 1, January 2006, pp. 9-16

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 9

Clark S, Westcott M and Taylor L (2007) 'Using short podcasts to reinforce

lectures',2007 National UniServe Conference, The University of Sydney.

Draper, S (2007) ‘Exploring Podcasting as Part of Campus-Based Teaching’,

Practice and Evidence of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in

Higher Education, 12: 1.

Edirisingha, P & Salmon, G (2007) Pedagogical Model for Podcasts in

Higher Education, LRA/BDRA, May 2007.

Gribbins, M (2007) The Perceived Usefulness of Podcasting in Higher

Education: A Survey of Students’ Attitudes and Intention to Use,

Proceedings of the Second Midwest United States Association for

Information Systems, Springfield, IL May 18-19, 2007

Huann, T and Thong, M (2006) ‘Audioblogging and Podcasting in

Education’, Education Ministry, Government of Singapore.

http://www.moe.gov.sg/edumall/rd/litreview/audioblogg_podcast.pdf

Knight, R. (2006) Podcasting Pedagogy divides opinion at US Universities.

Financial Times

9/2/06

Lane, C. (2006) UW Podcasting: Evaluation of Year One. University of

Washington.

Available from:

http://catalyst.washington.edu/research_development/papers/2006/podcas

ting_year1.pdf

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 10

Lee, M, McLoughlin, C and A. Chan (2008) ‘Talk the talk: Learner-generated

podcasts as catalysts for knowledge creation ’, in British Journal of

Educational Technology, Vol 39/ 3, pp. 501–521.

Lim, K.Y.T. (2006). ‘Now hear this – exploring podcasting as a tool in

geography education’.

In Purnell, K., Lidstone, J., & Hodgson, S. (Eds.). Changes in Geographic

Education: Past,

Present and Future. Proceedings of the International Geographical Union.

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, On the Horizon

(NCB University Press, Vol. 9 No. 5, October 2001)

SDDU (2007) ‘Podcasting’

http://www.sddu.leeds.ac.uk/online_resources/podcasting/index.html

Swain, H., 2006, ‘Let them tune in’, The Times Higher, Feb 3rd.

(summarised on http://www.lums.lancs.ac.uk/news/7196/

Polcasting, HEA Annual Conference, July 1st 2008 Page 11

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- STAR Method: How To Answer Behavioral Interview Questions (10+ Tips)Document12 pagesSTAR Method: How To Answer Behavioral Interview Questions (10+ Tips)Angeline Ventabal100% (4)

- MLHP 2905Document2 pagesMLHP 2905Mahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- Climate ChangeDocument2 pagesClimate ChangeMahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- 1 Pre and Post Conferance For Clinical PlacementDocument6 pages1 Pre and Post Conferance For Clinical PlacementMahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Nursing Student Clinical Placement ManualDocument14 pagesUndergraduate Nursing Student Clinical Placement ManualMahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- Seminar 2Document1 pageSeminar 2Mahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- Hip Fracture and Pneumonia Case StudyDocument3 pagesHip Fracture and Pneumonia Case StudySuleiman AbdallahNo ratings yet

- Physical Examination NormalDocument2 pagesPhysical Examination NormalMahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Taking A Patient's History PDFDocument7 pagesA Guide To Taking A Patient's History PDFAmrutesh KhodkeNo ratings yet

- Physical Examination NormalDocument2 pagesPhysical Examination NormalMahaveer swarnkarNo ratings yet

- CS1 Course OutlineDocument2 pagesCS1 Course Outlineapi-27149177No ratings yet

- WR VX Simulator Users Guide 6.9Document138 pagesWR VX Simulator Users Guide 6.9danielghroNo ratings yet

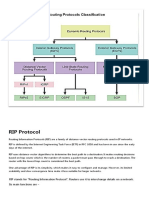

- RIP ProtocolDocument4 pagesRIP ProtocolDion Odessy PaduaNo ratings yet

- Premium Telecom Patch Cords: Features ApplicationsDocument2 pagesPremium Telecom Patch Cords: Features ApplicationsAmir SalahNo ratings yet

- Javascript PDFDocument22 pagesJavascript PDFJothimani Murugesan KNo ratings yet

- KOHA Integrated Library Management SystemDocument7 pagesKOHA Integrated Library Management SystemMehboob NazimNo ratings yet

- Prvo Ime ZadnjeDocument1 pagePrvo Ime ZadnjeEmir BuljubašićNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Lab 10-1, Securing Layer 2 Switches: InstructorDocument33 pagesChapter 10 Lab 10-1, Securing Layer 2 Switches: InstructorSantiagoNo ratings yet

- Datasheet Gxv3500 EnglishDocument2 pagesDatasheet Gxv3500 EnglishEnrique RamosNo ratings yet

- (November-2019) Braindump2go New PCNSE Dumps With VCE and PDF Free ShareDocument6 pages(November-2019) Braindump2go New PCNSE Dumps With VCE and PDF Free Shareshinde_jayesh2005No ratings yet

- Nimble Storage Data MigrationDocument10 pagesNimble Storage Data MigrationSomNo ratings yet

- Computer Gaming World OctDocument112 pagesComputer Gaming World Octapi-3808087100% (3)

- AirPrime MC7430Document108 pagesAirPrime MC7430sellabiNo ratings yet

- Image Based Registration and Authentication System: Aksr0201@stcloudstate - Edu Deve0301@stcloudstate - EduDocument5 pagesImage Based Registration and Authentication System: Aksr0201@stcloudstate - Edu Deve0301@stcloudstate - Edumd rizwanNo ratings yet

- MBT2 - Course of Study - Technological Globalization - 3 CUsDocument24 pagesMBT2 - Course of Study - Technological Globalization - 3 CUsjohann garciaNo ratings yet

- Edward S. Hloomstrong: Civil EngineerDocument2 pagesEdward S. Hloomstrong: Civil EngineerAthinaNo ratings yet

- Weblogic Suite Data SheetDocument9 pagesWeblogic Suite Data SheetNihal SinghNo ratings yet

- NASA Scientist Finds Evidence of Alien LifeDocument4 pagesNASA Scientist Finds Evidence of Alien LifeArnoldBlackNo ratings yet

- WiiDocument42 pagesWiiLeonie KremerNo ratings yet

- Tips For Writing Reflective LogsDocument2 pagesTips For Writing Reflective LogsjldcrzNo ratings yet

- Software-Defined Networks: A Systems ApproachDocument38 pagesSoftware-Defined Networks: A Systems Approachlino CentenoNo ratings yet

- PAN Online ProcessDocument27 pagesPAN Online ProcessAnonymous 3vj2VqNo ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsDocument3 pagesDigital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsElewanya UnoguNo ratings yet

- Opportunities and Challenges in Media and Information (Lec)Document21 pagesOpportunities and Challenges in Media and Information (Lec)ERnzkie ChecheNo ratings yet

- English 1asDocument33 pagesEnglish 1asSënörïtä Mähböülïstä Rïtä75% (8)

- 01.radware DefensePro Tech SpecDocument3 pages01.radware DefensePro Tech SpecLe Vinh HienNo ratings yet

- Cscape 9.0 Release Notes: Cscape 9.0 Available For Immediate DownloadDocument2 pagesCscape 9.0 Release Notes: Cscape 9.0 Available For Immediate DownloadNEDiver2No ratings yet

- Daet, Camarines Norte: Our Lady of Lourdes College Foundation Senior High School Department Empowerment TechnologiesDocument6 pagesDaet, Camarines Norte: Our Lady of Lourdes College Foundation Senior High School Department Empowerment TechnologiesJosua GarciaNo ratings yet

- Query SheetDocument18 pagesQuery Sheetabijith ta0% (1)