Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vieira 2019

Uploaded by

belina metri lidiasariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vieira 2019

Uploaded by

belina metri lidiasariCopyright:

Available Formats

Late Ophthalmologic Referral of Anisometropic Amblyopia:

A Retrospective Study of Different Amblyopia Subtypes

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Referenciação Tardia da Ambliopia Anisometrópica: Estudo

Retrospetivo dos Diferentes Subtipos de Ambliopia

Maria João VIEIRA1,2, Sandra Viegas GUIMARÃES3,4,5, Patrício COSTA3,4,6, Eduardo SILVA7,8,9

Acta Med Port 2019 Mar;32(3):179-182 ▪ https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.10623

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Amblyopia requires a timely diagnosis and treatment to attain maximum vision recovery. Specialty literature is lacking on

how early amblyopia is referred. We aimed to understand if there are mean age differences at first referral for ophthalmologic tertiary

center consultation among non-amblyopic and different types of amblyopia, in a context of lack of population screening.

Material and Methods: In this retrospective model, the sample corresponded to all children born in Braga Hospital during 1997 - 2012

(3 - 18 years-old), with an ophthalmologic consultation in 2014. Data was collected from the clinical records and children were divided

in a non-amblyopic versus amblyopic group. The amblyopic group was subdivided in strabismic versus refractive (anisometropic/

bilateral).

Results: The sample had a total of 1665 participants, 1369 (82.2%) without amblyopia and 296 (17.8%) with amblyopia. Among

amblyopia: 67.9% (n = 201) refractive, 32.1% (n = 95) strabismic. Within refractive amblyopia: 63.7% (n = 128) anisometropic and

36.3% (n = 73) bilateral. The mean age at first consultation was 6.24 ± 3.90 years-old: 6.39 ± 3.98 for non-amblyopic and 5.76 ± 3.58

for amblyopic. Among amblyopia subgroups, there were significant differences in mean age at first consultation (F3,1250 = 8.45; p < 0.001;

η2 = 0.020). Strabismic and bilateral refractive amblyopia were referred earlier, when compared to non-amblyopia or anisometropic

amblyopia (p < 0.05). Anisometropic amblyopia had the highest first consultation mean age: 6.92 ± 3.57 years-old.

Discussion: Without specific pre-school screening, children with amblyopia were referred to their first ophthalmologic evaluation

significantly later than desired, especially anisometropic amblyopia, with a postschool mean age for first consultation.

Conclusion: Recognizing high-risk children is essential for earlier referral and helps minimize future visual handicap.

Keywords: Amblyopia/epidemiology; Anisometropia/epidemiology

RESUMO

Introdução: A ambliopia requer uma abordagem atempada para uma máxima recuperação visual. Não existe informação sobre a

idade de referenciação da ambliopia. O presente artigo pretende perceber se há diferenças na idade média de referenciação para

consulta terciária de Oftalmologia, entre não-amblíopes e amblíopes, num contexto sem rastreio implementado.

Material e Métodos: A amostra correspondeu a todas as crianças nascidas no Hospital de Braga entre 1997 - 2012 (3 - 18 anos

de idade), com consulta de Oftalmologia em 2014. A informação foi recolhida pelos registos clínicos, tendo sido criado o grupo não-

amblíope e amblíope, dividido em estrábico e refrativo (anisometrópico/bilateral).

Resultados: A amostra contemplou 1665 participantes, 1369 (82,2%) não-amblíopes e 296 (17,8%) amblíopes. Dentro das ambliopias:

67,9% (n = 201) refrativas e 32,1% (n = 95) estrábicas. Nas ambliopias refrativas: 63,7% (n = 128) anisometrópicas e 36,3% (n = 73)

bilaterais. A média de idades na primeira consulta foi de 6,24 ± 3,90 anos, 6,39 ± 3,98 nos não-amblíopes e 5,76 ± 3,58 nos amblíopes.

Dentro dos subgrupos de ambliopia, existiram diferenças significativas na idade na primeira consulta (F3,1250 = 8,45; p < 0,001; η2 =

0,020). As ambliopias estrábicas e as refrativas bilaterais foram referenciadas mais cedo, quando comparadas com não-amblíopes

ou ambliopias anisometrópicas (p < 0,05). A ambliopia anisometrópica teve a maior média de idade na primeira consulta: 6,92 ± 3,57

anos de idade.

Discussão: Sem um rastreio pré-escolar específico, os amblíopes foram referenciados para a primeira observação oftalmológica

significativamente mais tarde do que o desejado, especialmente a ambliopia anisometrópica, com uma idade pós-escolar de média

para a primeira avaliação oftalmológica.

Conclusão: Identificar crianças de alto risco é essencial para uma referenciação precoce, ajudando a minimizar consequências

visuais.

Palavras-chave: Ambliopia/epidemiologia; Anisometropia/epidemiologia

INTRODUCTION

One of the major causes of monocular blindness is am- caused by sensory deficits during the critical period of visual

blyopia, being therefore regarded as a public health prob- development, such as strabismus, high refractive errors or

lem.1-3 Amblyopia is a neurodevelopmental vision disorder visual deprivation.4

1. School of Medicine. University of Minho. Braga. Portugal.

2. Department of Ophthalmology. Hospital de Santo André. Centro Hospitalar de Leiria. Leiria. Portugal.

3. Life and Health Sciences Research Institute. School of Medicine. University of Minho. Braga. Portugal.

4. ICVS/3Bs. PT Government Associate Laboratory. Braga/Guimarães. Portugal.

5. Department of Ophthalmology. Hospital de Braga. Braga. Portugal.

6. Clinical Academic Center-Braga. Braga. Portugal.

7. Centro Cirúrgico de Coimbra. Coimbra. Portugal.

8. IBILI. Faculty of Medicine. University of Coimbra. Coimbra. Portugal.

9. Department of Ophthalmology. Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte. Lisbon. Portugal.

Autor correspondente: Maria João Vieira. vieiramjp@gmail.com

Recebido: 05 de abril de 2018 - Aceite: 23 de outubro de 2018 | Copyright © Ordem dos Médicos 2019

Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos 179 www.actamedicaportuguesa.com

Vieira MJ, et al. Late ophthalmologic referral of anisometropic amblyopia, Acta Med Port 2019 Mar;32(3):179-182

Treating amblyopia improves visual acuity, binocularity The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality,

and decreases the likelihood of developing severe visual which was confirmed in all tested variables of the sample.

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

handicaps later in life.5 Despite these effects,6 maximum Levene’s test was used to evaluate variance homogeneity,

visual recovery declines after a non-consensual threshold having revealed heteroskedasticity of all tested variables

age that can go up to 7 years of age.7-9 Prompt amblyopia of the sample. Therefore, the Welch’s F test was used to

detection is, therefore, mandatory.5,10-18 compare amblyopia subgroups regarding mean age at first

The latest USPFTS guidelines19 state that “studies di- consultation, with multiple comparisons being done with the

rectly evaluating the effectiveness of screening were limited Games-Howell test. A one sample t test was used to com-

and do not establish whether vision screening in preschool pare the age means in the first consultation and an optimal

children is better than no screening”. theoretical first evaluation age.

Unfortunately, data is lacking on how amblyopia is treat- Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical

ed and prevented, as well as when the first ophthalmologic Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 22®).

appointment is made in Portugal.20 Two-sided p-values < 0.05 (95% confidence interval) were

In this study we have characterized the age at first oph- considered statistically significant. Two different effect size

thalmologic evaluation in Braga Hospital (Portugal), prior to measures were calculated: partial eta squared (ηp2) [small

an amblyopia prevention project.21 in order to understand 0.01, medium 0.06, large 0.14] and Cohen’s d scores [small

if different subtypes of functional amblyopia (versus non- 0.2, medium 0.5, large 0.8].25,26

amblyopic children) are referred in different ages. In sum,

we addressed the question: Are there differences in the RESULTS

mean age at first ophthalmologic evaluation between non- The sample had a total of 1665 participants [832 fe-

amblyopic versus amblyopic children, as well as between male (49.9%)], with a mean age of 8.64 ± 3.92 years-old.

functional amblyopia subtypes: refractive amblyopia versus Within the sample, there were 1369 subjects (82.2%) with-

strabismic amblyopia? out amblyopia and 296 subjects (17.8%) with amblyopia.

Among amblyopia cases, 67.9% (n = 201) corresponded to

MATERIAL AND METHODS the refractive subtype and 32.1% (n = 95) to the strabismic

We performed a retrospective study, reviewed and ap- subtype. Within refractive amblyopia: 63.7% (n = 128) had

proved by the local ethics committee of the Braga Hospi- anisometropic amblyopia and 36.3% (n = 73) had bilateral

tal. The sample corresponded to all children born in Braga refractive amblyopia.

Hospital during 1996 - 2011 (3 to 18 years-old in collection The mean age at first consultation was 6.24 ± 3.90

time), with an ophthalmologic consultation in 2014. Oph- years-old: 6.39 ± 3.98 in the non-amblyopia group and 5.76

thalmologic information present in the electronic clinical ± 3.58 in the amblyopia group. Mean age at first consulta-

database (Global Intelligence Technologies, Glintt®) was tion had significant differences among the three amblyopia

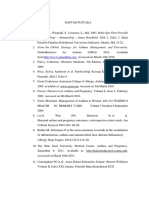

collected for this study. subgroups (p < 0.001; η2 = 0.020) (Table1).

Amblyopia was diagnosed as previously described in22 Strabismic and bilateral refractive amblyopia had a sig-

and included registration of occlusive treatment in addition nificantly lower age, when compared to non-amblyopia (p

to strabismus or refractive error. In cases without occlusive = 0.008 and p = 0.002, respectively) or to anisometropic

treatment, the inclusion criteria for anisometropic amblyopia amblyopia (p = 0.003 and p = 0.001, respectively) (Table 2

was: an interocular difference of ≥ 2 lines in best-corrected and Fig. 1). Anisometropic amblyopia had the highest mean

visual acuity (BCVA) and an amblyogenic refractive error age at first consultation: 6.92 ± 3.57 years-old, with no sig-

(ARE) responsible for that difference.1,23 For bilateral refrac- nificant differences when compared to non-amblyopia. (Fig.

tive amblyopia, the criteria was: ARE present plus bilateral 1). Strabismic amblyopia had the lowest median and bilat-

BCVA < 5/10 in 3 or 4-year-old subjects or ARE plus bilat- eral refractive amblyopia the lowest mean (Table 1), despite

eral BCVA < 8/10 in 5+ year-old subjects.21 Children who no statistically significant differences having been found be-

had unilateral and bilateral criteria where classified as bilat- tween these two groups.

eral amblyopia, as in Friedman et al24 Strabismic amblyopia Significant differences were found in the mean age of

included combined strabismic plus refractive amblyopia. amblyopia first consultation (5.76 ± 3.58 years-old) and an

The diagnosis was reviewed by a trained ophthalmologist. optimal theoretical first evaluation age of: 3 years-old (t281 =

Organic amblyopia cases were excluded. The age at first 12.9, p < 0.001, d = 1.54), 4 years-old (t281 = 8.22, p < 0.001,

ophthalmologic consultation was also collected. d = 0.98) and 5 years-old (t281 = 3.54, p < 0.001, d = 0.42).

Table 1 – Multiple pairwise comparisons: Games-Howell post-hoc test

Bilateral refractive Strabismic Anisometropic

No amblyopia

amblyopia amblyopia amblyopia

No amblyopia 1.73; p = 0.002 1.34; p = 0.008

Anisometropic amblyopia 2.26; p = 0.001 1.88; p = 0.003

Only statistically significant results were reported

Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos 180 www.actamedicaportuguesa.com

Vieira MJ, et al. Late ophthalmologic referral of anisometropic amblyopia, Acta Med Port 2019 Mar;32(3):179-182

** in anisometropic and bilateral. Our study finds an even lat-

** ter detection for refractive amblyopia and especially for ani-

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

** sometropic amblyopia, with a postschool mean age of 6.92

8

**

years-old for anisometropic amblyopia. Anisometropic am-

First consultation mean age

blyopia comprises almost 2/3 of refractive amblyopia cases,

6 reinforcing its problematic later detection.

Our study considers bilateral plus unilateral refractive

amblyopia as bilateral refractive amblyopia, since the clini-

4

cal signs and symptoms are probably due to the bilateral

aspect. This methodology leads to a higher bilateral refrac-

tive amblyopia prevalence than it was previously reported.1

2

Bilateral refractive amblyopia has the earliest referral of all

subgroups: the mean age at first consultation is significantly

0 lower than non-amblyopia or than anisometropic amblyo-

No_Amb Aniso_A Bila_Ref_A Stra_A pia. We speculate this could be also due to a possible posi-

Subgroups tive family history of high degree refractive error that could

Figure 1 – First consultation mean age in the different amblyopia lead to an early referral.

subgroups. First consultation mean age had significant differences Amblyopia is almost 5 times more prevalent than ex-

among the amblyopia subgroups (p < 0.001; η2 = 0.020): strabis- pected1,31,32 in the pediatric population of Braga Hospital,

mic and bilateral refractive amblyopia had statistically lower age, which is easily justified by the highly differentiated hospital

when compared to non-amblyopia (p = 0.008 and p = 0.002, re-

population (tertiary center bias).

spectively) or to anisometropic amblyopia (p = 0.003 and p = 0.001,

respectively). As a limitation of our study, age at first consultation was

No_Amb: no amblyopia; Aniso_A: anisometropic amblyopia; Bila_Ref_A: bilateral refrac- recorded in years: having collected the age in months would

tive amblyopia; Stra_A: trabismic amblyopia. **: p < 0.01

have brought more accuracy to our study, but this was not

possible due to its retrospective nature and the lack of avail-

DISCUSSION able information in medical records.

Children with amblyopia were referred to their first oph-

thalmologic evaluation significantly later than desired, pos- CONCLUSION

sibly explained by the lack of population-based screening. Refractive amblyopia is the major functional amblyopia

Anisometropic amblyopia was referred later than all sub- subtype. The division of refractive amblyopia in bilateral re-

groups (p < 0.05), while strabismic and bilateral refractive fractive amblyopia and anisometropic amblyopia is the key

amblyopia had the lowest mean age at first consultation. and innovative point of this study, giving us a new insight on

This is possibly due to the fact that anisometropic amblyo- this complex pathology.

pia conveys no signs of suspicion, while in strabismic and Without no population-based vision screening at the

bilateral refractive amblyopic children belonging to high-risk time of data collection, this late detection may consequently

groups, there is an objective evidence of squint in strabis- lead to amblyopia treatment after the age limit threshold (up

mus or difficulty in performing visual tasks in high bilateral to 7 years-old) and, possibly, an irreversible lower vision re-

ametropias that are easily seen by pediatricians, general covery.

practitioners or even by parents.27-29 In summary, anisometropic amblyopia screening by

Chua et al27 and Groenewoud et al30 also found that re- pediatricians or general practitioners is not as effective

fractive amblyopia is detected later, between 3.3 and 4.5 as strabismic or bilateral refractive amblyopia detection.

years of age. However, they did not split refractive subtype It seems important to have an organized preschool vision

Table 2 – Statistical tests for mean age at first consultation among amblyopia subgroups

Central Tendency Measurements Welch F test

Anisometropic Bilateral refractive Strabismic p value and

No amblyopia

ambylopia amblyopia amblyopia effect size

Age at 1st consultation

n = 1369 n = 128 n = 73 n = 95 F(3, 1250) = 8.45

M ± SD = 6.39 ± 3.98 M ± SD = 6.92 ± 3.57 M ± SD = 4.66 ± 2.96 M ± SD = 5.04 ± 3.61 p < 0.001

Mdn ± IQR = 6 ± 5 (3 - 8) Mdn ± IQR = 6 ± 5 (5 - 9) Mdn ± IQR = 5 ± 5 (2 - 7) Mdn ± IQR = 4 ± 5 (2 - 7) η2 = 0.020

n: number of subjects; M ± SD: mean ± standard deviation; Mdn ± IQR: median ± interquartile range

p: p value, statistically significant when p < 0.05; ηp2: partial eta squared (small 0.01, medium 0.06, large 0.14)

Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos 181 www.actamedicaportuguesa.com

Vieira MJ, et al. Late ophthalmologic referral of anisometropic amblyopia, Acta Med Port 2019 Mar;32(3):179-182

screening with refractive error detection and/or visual acuity use at their working center regarding patients’ data publica-

measurement. tion.

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

PROTECTION OF HUMANS AND ANIMALS CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that the procedures were followed All authors report no conflict of interest.

according to the regulations established by the Clinical Re-

search and Ethics Committee and to the Helsinki Declara- FUNDING SOURCES

tion of the World Medical Association. This research received no specific grant from any fund-

ing agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sec-

DATA CONFIDENTIALITY tors.

The authors declare having followed the protocols in

REFERENCES

1. Wallace DK, Repka MX, Lee KA, Melia M, Christiansen SP, Morse CL, et 16. Lagreze WA. Vision screening in preschool children: do the data support

al. Amblyopia preferred practice pattern(R). Ophthal. 2018;125:105-42. universal screening? Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:495-9.

2. Wong AM. New concepts concerning the neural mechanisms 17. Hopkins S, Sampson GP, Hendicott P, Wood JM. Review of guidelines

of amblyopia and their clinical implications. Can J Ophthalmol. for children’s vision screenings. Clin Exp Optom. 2013;96:443-9.

2012;47:399-409. 18. Cotter SA, Miller JM, Quinn GE. Vision screening for children 36 to 72

3. Buch H, Vinding T, La Cour M, Nielsen NV. The prevalence and months: recommended practices. Opto Vision Sci. 2014; 92:6-16.

causes of bilateral and unilateral blindness in an elderly urban Danish 19. Jonas DA, Wallace IF, Feltner C, Vander Schaaf EB, Brown CL,

population. The Copenhagen City Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. Baker C. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: a

2001;79:441-9. systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA.

4. Chua B, Mitchell P. Consequences of amblyopia on education, 2017;318:845-58.

occupation, and long term vision loss. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1119- 20. Lanca C, Serra H, Prista J. Strabismus, visual acuity, and uncorrected

21. refractive error in portuguese children aged 6 to 11 years. Strabismus.

5. Tarczy-Hornoch K, Cotter SA, Borchert M, McKean-Cowdin R, Lin J, 2014;22:115-9.

Wen G, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in Asian 21. Guimaraes S, Fernandes T, Costa P, Silva E. Should tumbling E go out of

and non-Hispanic white preschool children: Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye date in amblyopia screening? Evidence from a population-based sample

Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1220-6. normative in children aged 3-4 years. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:761-6.

6. Rutstein RP. Contemporary issues in amblyopia treatment. Optometry. 22. Guimaraes S, Vieira M, Queiros T, Soares A, Costa P, Silva E. New

2005;76:570-8. pediatric risk factors for amblyopia: strabismic versus refractive. Eur J

7. Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM, Harvey I. Amblyopia Ophthalmol. 2018;28:229-33.

treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years: follow up 23. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Pattern®

from randomised trial. BMJ. 2002;324:1549. Guidelines: Amblyopia. San Francisco: AAO; 2012.

8. Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM, Harvey I. Amblyopia 24. Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J. Prevalence of amblyopia and

treatment outcomes after preschool screening v school entry screening: strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71

observational data from a prospective cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. months: The Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology.

2003;87:988-93. 2009;116:2128-34.

9. Holmes JM, Lazar EL, Melia BM, Astle WF, Dagi LR, Donahue SP, et 25. Kotrlik JW, Williams HA. The incorporation of effect size in information

al. Effect of age on response to amblyopia treatment in children. Arch technology, learning, and performance. Infor Tech, Lear and Perfor Jour.

Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1451-7. 2003;21:1-7.

10. Donahue SP, Arthur B, Neely DE, Arnold RW, Silbert D, Ruben JB. 26. Cohem J. Statistical power and analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd

Guidelines for automated preschool vision screening: a 10-year, ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

evidence-based update. J AAPOS. 2013;17:4-8. 27. Brian BE, Johnson K, Martin F. A retrospective review of the associations

11. Forcina BD, Peterseim MM, Wilson ME, Cheeseman EW, Feldman S, between amblyopia type, patient age, treatment compliance and referral

Marzolf AL, et al. Performance of the spot vision screener in children patterns. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32:175-9.

younger than 3 years of age. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;178:79-83. 28. Membreno JH, Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Beauchamp GR.

12. Koning HJ, Groenewoud JH, Lantau VK. Effectiveness of screening for A cost-utility analysis of therapy for amblyopia. Ophthalmology.

amblyopia and other eye disorders in a prospective birth cohort study. J 2002;109:2265-71.

Med Screen. 2013;20:66-72. 29. Group Tpedi. The clinical profile of moderate amblyopia in children

13. Joish VN, Malone DC, Miller JM. A cost-benefit analysis of vision younger than 7 years. Arch Ophthalmology. 2002;120:281-7.

screening methods for preschoolers and school-age children. J AAPOS. 30. Groenewoud JH, Tjiam AM, Lantau VK. Rotterdam amblyopia screening

2003;7:283-90. effectiveness study: detection and causes of amblyopia in a large birth

14. Solebo AL, Cumberland PM, Rahi JS. Whole-population vision screening cohort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3476-84.

in children aged 4–5 years to detect amblyopia. Lancet. 2015;385:2308- 31. Pai AS, Rose KA, Leone JF. Amblyopia prevalence and risk factors in

19. Australian preschool children. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:138-44.

15. Schmucker C, Grosselfinger R, Riemsma R. Effectiveness of screening 32. Hendler K, Mehravaran S, Lu X, Brown SI, Mondino BJ, Coleman AL.

preschool children for amblyopia: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. Refractive errors and amblyopia in the UCLA Preschool Vision Program;

2009;9:3. first year results. Am J Ophthalmology. 2016;172:80-6.

Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos 182 www.actamedicaportuguesa.com

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 11Document33 pages11belina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustakabelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Jurnal AnDocument15 pagesJurnal Anbelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustakabelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Red Blood Cell Transfusion Guide for Anemia and Blood LossDocument6 pagesRed Blood Cell Transfusion Guide for Anemia and Blood Lossbelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- AnestesiDocument257 pagesAnestesibelina metri lidiasari0% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Daftar Pustaka AnesDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Anesbelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Tutor Sesi 1 Skenario CDocument20 pagesTutor Sesi 1 Skenario Cbelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Lampiran 1: A. Jenis Kelamin BalitaDocument6 pagesLampiran 1: A. Jenis Kelamin Balitabelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Laporan Skenario C FixDocument43 pagesLaporan Skenario C Fixbelina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Scenario A Block 17Document45 pagesScenario A Block 17belina metri lidiasariNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Cornea-Anatomy and PhysiologyDocument10 pagesCornea-Anatomy and PhysiologyMido KimoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- AR 2009-2010 WebDocument36 pagesAR 2009-2010 WebOsu OphthalmologyNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 2006, Vol.19, Issues 4, Cataract Surgery in The New MillenniumDocument117 pages2006, Vol.19, Issues 4, Cataract Surgery in The New MillenniumPatriciaChRistianiNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Corneal Drawing and Other StructureDocument2 pagesCorneal Drawing and Other StructureOden Mahyudin50% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Ghrita in Timira (Myopia) : A Clinical Study On The Role of Akshi Tarpana With JeevantyadiDocument6 pagesGhrita in Timira (Myopia) : A Clinical Study On The Role of Akshi Tarpana With JeevantyadiPNo ratings yet

- Achieving Excellence in Cataract Surgery - Chapter 14Document8 pagesAchieving Excellence in Cataract Surgery - Chapter 14CristiNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Bennett and Rabbetts Clinical Visual OpticsDocument472 pagesBennett and Rabbetts Clinical Visual OpticsShifan Abdul MajeedNo ratings yet

- CataractDocument52 pagesCataracttammycristobalmd100% (4)

- Buku Koding 1Document74 pagesBuku Koding 1indra_igrNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Livro - Contact Lenses, Anthony J. PhillipsDocument2,502 pagesLivro - Contact Lenses, Anthony J. PhillipsMily Pharma100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Questionnaire Survey Bases Awareness and Knowledge of Glaucoma Among Adult Patient in Rural and Urban Area in RaipurDocument3 pagesQuestionnaire Survey Bases Awareness and Knowledge of Glaucoma Among Adult Patient in Rural and Urban Area in RaipurInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of the Uvea: Iris, Ciliary Body and ChoroidDocument48 pagesAnatomy of the Uvea: Iris, Ciliary Body and ChoroidBinu AshrafNo ratings yet

- Physics Holiday HomeworkDocument9 pagesPhysics Holiday HomeworkB.M.V.Aditya XANo ratings yet

- Eye AssessmentDocument5 pagesEye AssessmentMabes100% (3)

- Summary - Ocular Manifestations of HIVDocument1 pageSummary - Ocular Manifestations of HIVRyan HumeNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology Explorer 1st EditionDocument373 pagesOphthalmology Explorer 1st EditionAaron French100% (3)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Glaucoma Practice Patterns of Philippine Glaucoma Society MembersDocument10 pagesGlaucoma Practice Patterns of Philippine Glaucoma Society MembersAdriane MonisNo ratings yet

- Skripsi Tanpa PembahasanDocument56 pagesSkripsi Tanpa PembahasanPutri EmNo ratings yet

- Arce Pachymetry Keratoconus - GALILEiDocument16 pagesArce Pachymetry Keratoconus - GALILEiRodolfo YiNo ratings yet

- Eye Anatomy DiagramDocument7 pagesEye Anatomy DiagramIon NagomirNo ratings yet

- Ocular PharmacologyDocument11 pagesOcular PharmacologyIgnacio NamuncuraNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Study To Correlate Visual Field Defects With Optic Disc Changes in 100 Patients With Primary Open Angle Glaucoma in A Tertiary Eye Care HospitalDocument3 pagesA Clinical Study To Correlate Visual Field Defects With Optic Disc Changes in 100 Patients With Primary Open Angle Glaucoma in A Tertiary Eye Care HospitalIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Phaco Cataract Surgery Package ChargesDocument1 pagePhaco Cataract Surgery Package ChargesNeyaz HasnainNo ratings yet

- Competency in Optometry ExaminationDocument4 pagesCompetency in Optometry ExaminationBen Joon100% (3)

- Coding Poli Mata: Papillitis H46 Hypertension Ocular:h40.0 Macula H35.8 Ptosis H02.4 Chalazion H00.1 Asthenopia H53.1Document1 pageCoding Poli Mata: Papillitis H46 Hypertension Ocular:h40.0 Macula H35.8 Ptosis H02.4 Chalazion H00.1 Asthenopia H53.1nurcasanNo ratings yet

- Ocular Trauma Triage and TreatmentDocument22 pagesOcular Trauma Triage and TreatmentuzubarselaNo ratings yet

- The Special Senses: Vision, Hearing, Taste, and SmellDocument31 pagesThe Special Senses: Vision, Hearing, Taste, and SmellDemuel Dee L. BertoNo ratings yet

- Vision TestDocument93 pagesVision TestAr JayNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Prevalence and Geographical Variations: Section 1 Glaucoma in The WorldDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Geographical Variations: Section 1 Glaucoma in The WorldGuessNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology Explained Sample 3-5-2021Document35 pagesOphthalmology Explained Sample 3-5-2021aleena naz.164No ratings yet