Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour: Interacting With Computers December 2013

Uploaded by

AndersonOliveiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour: Interacting With Computers December 2013

Uploaded by

AndersonOliveiraCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/275387261

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour

Article in Interacting with Computers · December 2013

DOI: 10.1093/iwc/iwt024

CITATIONS READS

6 129

5 authors, including:

Thomas Chesney Swee-Hoon Chuah

University of Nottingham RMIT University

57 PUBLICATIONS 737 CITATIONS 33 PUBLICATIONS 370 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Wendy Hui

Lingnan University

39 PUBLICATIONS 740 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Is Knowledge Cursed When Forecasting Others’ Forecast Accuracy? View project

Pension fund and Behavioral research View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Swee-Hoon Chuah on 01 June 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Interacting with Computers Advance Access published April 5, 2013

© The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The British Computer Society. All rights reserved.

For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

doi:10.1093/iwc/iwt024

A Study of Gamer Experience and

Virtual World Behaviour

Thomas Chesney1,∗ , Swee-Hoon Chuah1 , Robert Hoffmann1 , Wendy Hui2

and Jeremy Larner1

1 Nottingham University Business School, University of Nottingham, UK

2 Curtin

University of Technology, Perth, Australia

∗Corresponding author: thomas.chesney@nottingham.ac.uk

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

This paper reports a study which examined the impact of computer game experience on behaviour

observed inside a virtual world. A social networking world was used, which was owned and run by the

research team and a dataset capturing the behaviour of 195 subjects was extracted from the world’s

event logs. Four broad areas were analysed: communication, movement, avatar creation and world

customization. Highly significant differences were found in text communication. Less significant

differences were found in movement and avatar creation, and none were found in the customization

of the world.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

• Differences in behaviour between computer gamers and non-gamers in a novel social networking virtual

world are examined.

• The world is controlled by the research team and the team therefore have access to its detailed event logs.

• A range of virtual world telemetrics are examined using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

• Difference between gamers and non-gamers were found in chat, avatar movement and avatar creation.

Keywords: user studies, social media, massively multiplayer online

Editorial Board Member: Paul Cairns

Received 10 December 2012; Revised 6 March 2013; Accepted 11 March 2013

1. INTRODUCTION platform games such as Sonic the Hedgehog; and Mafia Wars

A virtual world is a persistent computer-mediated environment to management simulations such as Football Manager. Even

in which many users can synchronously interact (Bell, 2008). early text-based virtual worlds such as MUD used a style of

The past decade has seen much research interest in virtual interaction that was based on games such as Colossal Cave

worlds (Wasko et al., 2011). Their genesis lies in computer Adventure.

games (Messinger et al., 2008b; Schroeder, 1997) and the most However, not all virtual worlds are games. Second Life as a

popular worlds are still games. World of Warcraft, EVE Online whole is difficult to classify as a game (Schultze and Rennecker,

and Ultima Online are good examples and each features a 3D 2007) and is better described as an ‘arena of creativity’(Chesney

interface with users represented as avatars (Fig. 1)1 . et al., 2009) or a ‘virtual “place” rather than a game’ (Turkle,

Not all virtual worlds have as sophisticated interfaces as 2011), a place where sometimes work, rather than play, gets

these. Maplestory uses a relatively primitive sideways scrolling done (Terdiman, 2007). Slater et al. (2000) provide a concise

interface and Mafia Wars which is also arguably a virtual discussion of how virtual worlds are useful for collaborative

world has a largely text-based interface. In each case, however, work and have advantages over technologies such as video

the interface used can be traced back to a game: World of conferencing. In addition, some in the IT industry think that

Warcraft to Doom and Tomb Raider; Ultima Online to Gauntlet the skills needed to manage virtual worlds are inherently useful

and the original Ultima; EVE Online to Elite; Maplestory to in the real business world (see, for instance, Chodos, 2009;

Driver and Jackson, 2008; Kirkpatrick, 2007) and that ‘serious

1 For information about the worlds and games mentioned see Appendix A. games’ have a role in training (Bohannon, 2010) and education

Interacting with Computers, 2013

2 Thomas Chesney et al.

might influence their ability to navigate around and interact in a

virtual world. In fact, when playing a computer game it is clear

that a gamer experienced in that game will behave differently

from a non-gamer. We take this statement as self-evident,

although it has been demonstrated experimentally (Hong and

Liu, 2003): when playing against an opponent of a certain skill,

an experienced player will behave in such a way that they tend

to win, a new player will tend to lose.

However, it might be expected that differences would also

be evident in an unfamiliar virtual environment even when the

purpose of use is not play. Theoretically such differences might

arise due to the interface’s game heritage. The theory behind this

work can therefore be summarized succinctly: virtual worlds

are no longer used solely for gaming (Verhagen et al., 2012)

and are therefore populated by both gamers and non-gamers;

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

virtual world interfaces are inspired by game interfaces; this

Figure 1. A typical virtual world scene.

means we might expect that those familiar with computer games

will behave differently in virtual worlds from those unfamiliar

(deNoyelles and Seo, 2012). Both Schultze and Orlikowski with games. This is the hypothesis which is tested. Ang et al.

(2010) and Chesney et al. (2009) list examples of virtual worlds (2007, p. 167) concisely explain why gamers and non-gamers

used for work rather than play. Jung and Kang (2010) distinguish might behave differently: ‘Whilst playing MMORPGs, users

gaming worlds from social worlds noting different motivations are required to multi-task. Most significantly, players must learn

of use for each. to deal with the social dynamics around the game in addition

With the interest in the use of virtual worlds for social to having to interact with the virtual space and game objects

networking, education and commerce, and given their game which are usually defined by the complicated game mechanics.

heritage, it is therefore interesting to ask how computer game This may cause cognitive overloads which can hinder the

experience influences behaviour in a virtual world, which is performance especially of beginner players’.

used for collaboration rather than play. This paper examines Schrader and McCreery (2008) find that subjects’ levels of

this question, reporting behaviours observed in 195 subjects, a computer gaming expertise does indeed relate to behaviours,

mixture of gamers and non-gamers, in a world that is new to all strategies, and skills exhibited within a virtual world. Other

of them. literature on this, which is reviewed next, is limited and does

not always relate explicitly to computer gamers interacting in

social networking virtual worlds. However, taken together, it

does tend to suggest that differences in behaviour might be

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

expected in four broad areas of virtual world interaction: avatar

Gaming experience (time spent playing computer games) is creation, communication, movement and world customization.

quite distinct from gaming expertise (being good at a computer Each is an important part of virtual world use (Taylor, 2002) and

game). Taylor et al. (2011), for instance, see gaming expertise each is readily observed in a virtual world (unlike, for instance,

as a construct made up of investment in the game, skill in the behaviour relating to the setup of a user’s computer such as the

game, mastery in the social language of gaming and knowledge distance they keep their virtual camera from their avatar; such

of the game. However, we define computer gamer in terms behaviour is not considered here). It is in these four areas that

of experience rather than expertise. A gamer in this study is we test our hypothesis.

someone who plays computer games frequently and perceives

themselves as a gamer but who is not necessarily an expert (e.g.

2.1. Avatar

can achieve a top score) in a game. Our classification of gamer

uses an ordinal scale with three levels: non-gamer, gamer and The avatar is fundamental to virtual worlds and modern

frequent gamer, with a self-reported distinction between gamer avatars exhibit an impressive range of characteristics and

and frequent gamer based on time spent playing. behaviours. Users are embodied through their avatar (Benford

Therefore ‘computer gamer’ here includes players of multi- et al., 1995), a self-representation which gives a mechanism

player games, first person perspective games, platform games for communicating and interacting with other users, and for

and puzzle games. In all but games which have the simplest navigating the world. The sense of presence users feel in the

interfaces, such as an electronic crossword puzzle or a Sudoko world tends to increase with avatar realism (Slater and Steed,

game, a computer gamer will have experience of navigating 2009) and even basic avatars (in a graphical sense) have social

and manipulating game elements on a computer screen. This significance (Slater et al., 2000). The design goal is to make

Interacting with Computers, 2013

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour 3

users feel as if they are inhabiting a body rather than just communicate quickly by typed text also necessitates it being

operating an animated figure (Slater et al., 2000). abbreviated.

Thus the avatar is key to online identity (Taylor, 2003). A Stepping away from one particular game’s or community’s

user’s avatar influences how others perceive them (Donath, jargon to a world that is new to all participants—as the world

2007; Nowak and Rauh, 2008) and users prefer to have control used here is—where such jargon does not yet exist, will an

over their avatar’s appearance (Messinger et al., 2008a). For experienced gamer’s chat still differ from that of non-gamers?

this reason, virtual world designers often give users a high This question has not been fully examined before, but two

degree of control over their ability to customize their avatar. papers have touched upon it and both suggest that there will

The relationship between user and avatar is complex and has be differences. Huffaker et al. (2009) study a number of gamer

been approached by researchers in a number of ways. Both types finding that those whose avatars have the highest ‘game

Messinger et al. (2008a) and Bessière et al. (2007) find that level’ send and receive more communication than others. Those

some users customize their avatars to bear similarity to their who perform most efficiently at the game show no difference

real selves. Other users experiment with a range of avatar in communication behavior from other players. In the second

looks (Taylor, 2002). Yee and Bailenson (2007) demonstrate paper, Jackson et al. (1999) study school children interacting

that avatar appearance has an impact on how people behave in pairs using voice chat in a virtual environment and find that

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

in world. Ducheneaut et al. (2009) study the choices subjects pairs of novices were less communicative than pairs of experts.

make when creating their avatar and find the effort they put in, in User gender made a difference, with pairs of female experts

terms of time spent, depends heavily on the virtual world. They communicating the most, although how ‘expert’ and ‘novice’

find no difference between effort put into creating an avatar for were defined is unclear.

World of Warcraft and Maplestory, but find Second Life users

put a significantly larger amount of effort into their avatars.

2.3. Movement

Trepte et al. (2009) report that avatars are chosen by gamers

so that they can be used (1) to master the game and (2) to be a Another important part of virtual world interaction is movement

character players can identify with. and navigation through the world. In considering movement

When considering what this means to gamer/non-gamer and navigation, it might be expected that someone who had

differences, it might be thought that gamers will tend to have played a computer game would be ‘better’ at it than someone

experience of avatar creation/customization, and of their self- who had not. The novice might be expected to explore less,

presentation preferences inside a virtual world, knowledge to bump into walls and to become stuck in corners. However,

that non-gamers will tend not to have. We would therefore given the ubiquity of human–computer interaction, it could

expect avatar customization to be determined in part by gamer be that such differences are less pronounced than they once

experience. Little has been written on this. One study finds were, with many non-gamers being very comfortable with

that all types of gamer (casual gamer, social gamer and heavy using mouse and keyboard and tracking movement on a

gamer) do not differ in their emphasis on avatar appearance monitor. At least one paper has found that players can be

and customization. Although interesting, it should be noted that classified by their avatar’s actions including movement and

casual gamer does not equate with non-gamer. that these classifications include experienced and inexperienced

Avatars are also used as a communication tool. They give players (Matsumoto and Thawonmas, 2004). In other words,

virtual world users a continual awareness of others in their experienced and inexperienced users do differ somehow in

shared space which on its own can be a powerful communication their movement. The analysis used data-mining techniques and

tool. For instance, a semi-circle of avatars around another how users differed was not reported. In fact, little has been

confers some sense of importance to, or attention on, the central written on this. Jackson et al. (1999) found among school

figure (Benford et al., 1995). In addition, avatar gestures such as children that expert users tend to involve themselves in more

pointing, yawning and smiling are used to communicate. Much action, that is they do more, than novices. Both Richardson

virtual world communication however is still chat-based. and Powers (2011) and Frey et al. (2007) find differences in

navigation performance between those with different levels

of experience. Related to movement is spatial proximity

among avatars. Striking differences in avatar distribution have

2.2. Communication

been observed (Lomanowska and Guitton, 2012) but the

Gamer chat, whether text or voice, is a confusing array of relationship of this to gamer experience has not been examined

abbreviations and jargon that is often incomprehensible to before.

outsiders (Turkle, 1995). In a discourse analysis of chat in

the virtual world Lineage, Steinkuehler (2004) shows that this

2.4. World customization

jargon-filled chat in fact serves the same range and complexity

as offline language, but looks the way it does due to the Another important feature in the formation of virtual worlds

tight constraints of the game’s chat window. The need to is the ability of individuals to customize their own space

Interacting with Computers, 2013

4 Thomas Chesney et al.

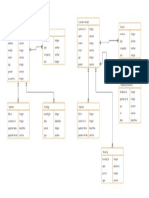

for a larger research project (Dieterle and Murray, 2010) of

which this study is a part. The research team had control of

the world and could access all the event logs, which meant

data on avatar behaviour could be easily extracted. Similar

in appearance to Second Life, the world is not a game but is

intended as a social networking space. The world’s asthetic is

modern day New York. It allows for text chat between avatars

and a range of avatar gestures but no audio. The main area

is a recreation of Times Square which avatars can explore

by walking (no running, jumping or flying). It features avatar

customization (Fig. 3) in terms of name, gender, body size

and shape, clothing, tattoos and jewellery. Each avatar has an

apartment with a bedroom, living room and hallway that can be

customized (Fig. 4) by putting up posters (photos from flickr)

and changing the style and colour of the walls and furniture. The

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

world features an integrated help system to explain its features

Figure 2. Places/Sherwood; the text chat interface can be seen in the to users.

bottom left.

4. METHOD

Subjects were asked to complete a demographics questionnaire

and then attend 1 of 20 experiment sessions in a computer

laboratory. The sessions involved between 8 and 12 subjects

positioned so that they could not clearly see each other’s

screens. Interaction with each other in the real world was

not allowed but in the virtual world it was encouraged.

Subjects stayed in the world for no less than 90 min. No

real world announcements were made after subjects were

logged in although two researchers were in-world and made

announcements from there. Socialization was encouraged with

an ice-breaker game led by the in-world researchers. The

experiment took place at two physical locations, in the UK

and in Dubai. Subjects were paid 5GBP (or the UAE dirham

equivalent) for attending. A dataset of 195 subjects was created.

Figure 3. The avatar creation interface.

4.1. Subject demographics

(Schroeder et al., 2001). This customization plays a part in Subjects were drawn from one population: those about

how the online community develops. With an object creation to leave higher education and enter work. Using standard

interface as complex as a world such as, for example, Second recruitment procedures from experimental economics and

Life (see Weber et al., 2007), it is understandable—and clearly applied psychology (Kagel and Roth, 1995), we contacted

observed in the world—that new user’s creations differ vastly representative groups from this population and invited them

from those of experienced users, in that they tend to be less to take part. Those that agreed were randomly assigned to a

impressive. However, questions on time and effort spent in session. We did not design the recruitment procedure to achieve

customizing an environment between gamers and non-gamers equal or target levels of gamers and non-gamers. Only post-

have not been examined before. recruitment did we determine by the questionnaire responses

who was a gamer and who was not.

Computer game experience was measured by two survey

questions giving three levels of experience: non-gamer (n = 49,

3. THE WORLD

25%), gamer (n = 83, 43%) and frequent gamer (n = 63, 32%)

The world used in this study, called Places/Sherwood (Fig. 2), giving total n = 195. The two questions were:

was developed by software developer Multiverse (which has

since ceased trading). An instance of the world was created (1) Do you play video games? [Yes/No]

Interacting with Computers, 2013

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour 5

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

Figure 4. Avatar apartments; on the left the avatar is about to change the appearance of her sofa; on the right the avatar is about to search flickr for

a photo to put up as a poster.

Table 1. Subject demographics (3) avatar design and (4) choices made to customize the world.

In the following analyses, based on gender differences found in

Non-gamers Gamers Frequent gamers

existing literature (Taylor, 2008), we control for the gender of

n (total) 49 83 63 the user and their avatar. To avoid problems with collinearity

n (UK) 41 52 28 we control for avatar gender with a dummy variable, ‘gender-

n (Dubai) 8 31 35 match’, which indicates whether user and avatar gender are the

% Male 24.5 48 79 same or different. To check for a potential problem of statisti-

Mean (SD) age 20.6 (1.9) 21.1 (3.5) 20.6 (2.0) cal non-independence caused by the data collection happening

Mean (SD) 3.6 (3.5) 10.5 (7.9) in sessions of 8–12 subjects (which might influence partici-

hours play pant behaviour through particular group dynamics and social

per week context), the analyses were repeated using a generalized linear

mixed model to test whether the session had an effect. The find-

ings showed that it did not, and it is the ordinary least squares

Table 2. Reasons given for not playing computer games, and regression results that are reported in the tables here. Our results

the percentage they appeared in the list of reasons given were also unaffected by the location of subjects, Dubai and UK.

Reason %

Lack of time 31

Uninterested 53 5. ANALYSES AND RESULTS

Computer games are addictive/harmful 10 5.1. Communication

Lack of access to games 6

About 1 MB of text chat data were collected featuring

approximately 7500 messages2 . Features of the text and

the message content were analysed using quantitative and

(2) Do you consider yourself a gamer (someone who plays qualitative methods, respectively.

video games frequently)? [Yes/No]

Table 1 presents information about the sample. Most (n = 5.1.1. Chat features analysis.

167) were not users of virtual worlds. Subjects had experience A quantative analysis was carried out by Wang et al. (2011) to

of a range of games with frequent gamers listing on average develop algorithms to automatically detect speaker attributes.

three games that they play the most. The most common games Their analysis used the current dataset as test data and we are

listed were third person action/adventure games (which have able to draw upon their results. The analysis examined a range

very similar interfaces to that shown in Fig. 1). Table 2 lists the of metrics which were extracted from the chat logs such as

reasons given by the non-gamers for why they do not play. 2A message is defined as the text that is sent when the user finishes typing

Analyses were conducted in the four areas: (1) communica- and presses enter. It does not necessarily equate to a sentence although almost

tion, (2) avatar movement, and environment choices including all messages were single sentences.

Interacting with Computers, 2013

6 Thomas Chesney et al.

quality of syntax, message length and use of extreme words Result 1. Experienced gamers write more sentences, and

such as ‘best’, ‘greatest’ and ‘super’. (Note that messages not longer sentences than less experienced gamers, more of what

written in English—a minority of about 30 messages from the they write are statements rather than questions, and they address

sessions in Dubai—were ignored although they were translated other users by avatar name more frequently.

by a professional paid translator and included in the qualitative

analysis reported in Section 5.1.2.) 5.1.2. Chat content analysis.

Results show that the number of messages, the average All chat was qualitatively analysed using content analysis where

number of characters per message, the average number of messages were coded into one of six categories and then

messages that address someone (such as ‘come on John’), into one of a number of sub-categories. Content analysis is a

the percentage of messages that were statements rather than useful technique to summarize and describe large qualitative

questions, were all significantly related to gamer experience data sets (Neuendorf, 2002). An inductive content analysis

(Table 3). was employed, deriving the categories directly from the data.

The data were coded according to the guidelines provided

by Elo and Kyngas (2008). The messages were read and re-

Table 3. Quantitative chat analysis, n = 170 (the lower n is read in order to become familiar with the content. During

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

because 25 users did not generate enough chat to be used in this the initial readings, a process of open coding was applied,

analysis) where all interesting concepts found within the data were noted

Coefficient SE t-value P -value and categories were freely generated. In the next stage, the

Number of messages categories were grouped into broader, higher-order categories

Gamer 13.75 3.55 3.88 0.000∗∗∗ and sub-categories. Finally, all categories and sub-categories

usergender 5.83 5.24 1.11 0.268 were assigned a clear label and a description. Once the coding

gendermatch 6.93 8.16 0.85 0.396 frame was established, all messages were read again and coded

vwuser 13.29 6.71 1.98 0.049∗ accordingly.

Adjusted R 2 0.16 Code classifications were made independently by one

researcher who was not involved in the data collection and a

Percentage of person addressing messages sub-set (500 messages, which is roughly 7% of the total) of the

Gamer 0.02 0.01 1.79 0.075† chat was independently classified by a second researcher (one

usergender 0.01 0.01 0.37 0.712 of the authors). When the classifications of each sentence were

gendermatch 0.04 0.02 1.77 0.079† examined for inter-rater reliability, there was 76.7% agreement

vwuser −0.01 0.02 −0.76 0.449 between the two. The agreement expected by chance was 7.6%

Adjusted R 2 0.03 and Cohen’s kappa was calculated to be 0.748, which indicates

Percentage of statements a good level of agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977).

Gamer 0.03 0.02 1.69 0.093† Six main categories made up of 17 subcategories were found.

usergender 0.04 0.02 1.90 0.059† The main six were:

gendermatch 0.03 0.04 0.75 0.456

(1) Providing help

vwuser −0.03 0.03 −1.16 0.247

(2) Asking for help

Adjusted R 2 0.06

(3) Follower/leader traits

Percentage of questions (4) Viewpoint (whether text about an avatar/user was

Gamer −0.02 0.01 −1.56 0.121 written in the first or third person, or whether references

usergender −0.04 0.02 −2.24 0.027∗ were made to the real world)

gendermatch −0.01 0.03 −0.49 0.628 (5) Attitude to others

vwuser 0.03 0.02 1.31 0.193 (6) Aggression

Adjusted R 2 0.07

The percentage of a subject’s messages that were coded in

Average message length in characters

each category was regressed as before. No differences between

Gamer 1.33 0.55 2.42 0.017∗

gamers and non-gamers were found in terms of asking for or

usergender −1.16 0.80 −1.44 0.151

providing help, and no difference was found in the personal

gendermatch −0.35 1.26 −0.28 0.783

remarks made about others. Gamers chat more as leaders

vwuser −1.61 0.99 −1.63 0.105

than non-gamers, and refer more to the real world than

Adjusted R 2 0.02

non-gamers (Table 4). ‘Chatting as a leader’ is instances of

∗∗∗ Significance at 0.001 level. statements or questions indicating the speaker’s willingness

∗∗ Significance at 0.01 level. to lead, making suggestions of group activities, influencing or

∗ Significance at 0.05 level.

encouraging others’ behaviours, taking control of group/other

†significance at 0.1 level. players activities and giving instructions. Examples include:

Interacting with Computers, 2013

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour 7

Table 4. Qualitative chat analysis, n = 195 Table 6. Movement analysis, n = 195

Coefficient SE t-value p-value Coefficient SE t-value p-value

Leader traits Total key presses

gamer 1.08 0.27 3.95 0.000∗∗∗ gamer 7.57 49.26 0.15 0.878

usergender 0.26 0.40 0.64 0.523 usergender 152.04 74.74 2.03 0.044∗

gendermatch 0.85 0.61 1.40 0.165 gendermatch −54.78 105.34 −0.52 0.604

vwuser −0.18 0.50 −0.35 0.726 Adjusted R 2 0.02

adjusted R 2 0.12 Turn left

Real world references gamer −0.88 15.76 −0.06 0.955

gamer 0.78 0.24 3.20 0.002∗∗ usergender 83.07 23.91 3.48 0.001∗∗∗

usergender 0.10 0.36 0.29 0.775 gendermatch −2.33 33.69 −0.06 0.945

gendermatch 0.03 0.54 0.05 0.962 Adjusted R 2 0.07

vwuser 0.96 0.45 2.14 0.03∗ Turn right

adjusted R 2 0.11 gamer 2.851 17.040 0.167 0.867

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

∗∗∗ Significance at 0.001 level. usergender 88.968 25.851 3.442 0.001∗∗∗

∗∗ Significance at 0.01 level. gendermatch −6.039 36.435 −0.166 0.869

∗ Significance at 0.05 level. Adjusted R 2 0.07005

†Significance at 0.1 level. Strafe left

gamer 1.23 0.73 1.69 0.093†

Table 5. Results of the qualitative chat analysis showing usergender 1.02 1.10 0.92 0.360

the number and percentage of messages in each of two gendermatch 1.16 1.61 0.72 0.470

subcategories (leader traits and references to the real world) Adjusted R 2 0.02

∗∗∗ Significance at 0.001 level.

Category Non-gamer Gamer Frequent gamer

∗∗ Significance at 0.01 level.

Leader 0.81 (1.12) 1.99 (2.39) 3.33 (3.41)

∗ Significance at 0.05 level.

0.03 (0.04) 0.06 (0.07) 0.06 (0.06)

Real world 0.19 (0.49) 0.72 (1.58) 1.88 (3.22) †Significance at 0.1 level.

0.01 (0.02) 0.02 (0.03) 0.03 (0.05)

The upper row is the mean (SD) number of messages in each

subcategory; the lower row is the mean (SD) percentage of

Taking key presses first, note that more than one key can

messages in each subcategory

produce the same movement, for instance, W and the Up Arrow

do the same thing, so we counted moves produced rather than

presses of a particular key. The moves available to be examined

were forward, backward, left, right, strafe left and strafe

‘Lets do this, guys!’, ‘daisy and dan…walk towards me’, right. We found gamer experience was correlated with strafe

‘nona come here’. References to ‘real world’ is commenting movements (r = 0.16, p = 0.02 for strafe left movements).

on the computer and its use, for example, by mentioning the When regressed with user gender we found the relationship held

keyboard or computer screen, the laboratory or other players at the 10% level of significance and incidentally also found big

in reality. Examples include ‘my computer screen IS dirty!’, differences in the movement behaviour of males and females

‘im hungry…’, ‘I’m getting cold’. Table 5 gives summary (Table 6), a finding that has been observed before (see Martens

information about these two sub-categories. and Antonenko, 2012).

A range of proximity measures were considered: the average

Result 2. The content of gamers’chat is largely indistinguish-

distance between an avatar and the next closest avatar; the next

able from that of non-gamers, but gamers are more likely to chat

closest male and female avatar; the next closest three avatars;

as leaders and to refer to the real world more.

and the next closest three male and three female avatars. The

total distance and the average speed of movement were also

analysed. No differences were found in the proximity gamers

5.2. Movement and non-gamers kept between themselves and other avatars

(although as before differences in user gender were found).

A substantial dataset on avatar movement was collected. The

current analysis considers the number of times each subject

pressed a key on the keyboard to move their avatar, what Result 3. Some differences were observed in the movement

movement the key produced, the distance subjects moved in behaviour of those with different levels of game experience but

the world and the proximity they kept to other avatars. these were not pronounced.

Interacting with Computers, 2013

8 Thomas Chesney et al.

5.3. Avatar design Table 11. Effort expended on avatar creation in terms of overall

effort and effect spent on choosing a top, n = 195

The avatar choices that all Places/Sherwood users must make

are gender, skin colour and clothing. Starting with gender, Coefficient SE t-value p-value

Table 7 shows the choices that subjects made. Table 8 shows Overall effort

the number of subjects who swapped gender, broken down by gamer 4.16 3.66 1.14 0.257

gamer experience. Using a χ 2 -test, no difference was found usergender −19.91 5.40 −3.69 0.000∗∗∗

between gamers and non-gamers (χ 2 = 0.02, p = 0.99). gendermatch −2.12 8.41 −0.25 0.801

Looking at skin colour, nine choices were available for vwuser 2.41 6.91 0.35 0.728

avatars. These represent ordinal data ranging from 1 (pale) to 9 Adjusted R 2 0.06

(dark). Table 9 shows the contingency table for the skin colour Choice of top

choices made against gamer experience. These nine skin colours gamer 1.72 0.88 1.96 0.051†

were merged into two categories, pale and dark with choices usergender −14.13 1.29 −10.93 0.000∗∗∗

1–6 being pale and 7–9 being dark (Table 10). Two observers gendermatch −0.60 2.01 −0.30 0.766

independently made this classification and agreed on this split. vwuser 2.14 1.66 1.29 0.199

Adjusted R 2 0.43

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

A χ 2 -test revealed no difference in avatar skin colour choice

∗∗∗ Significance

between gamer experience level (χ 2 = 1.77, p = 0.41). at 0.001 level.

∗∗ Significance

A crude measure of the effort that subjects put into their avatar at 0.01 level.

∗ Significance at 0.05 level.

creation was then created as follows. Each avatar characteristic

†Significance at 0.1 level.

Table 7. Gender of users and their avatars

Avatar

(body shape, clothing, etc.) was in a menu with up to 48

Male Female potential choices per characteristic. The measure used assumed

User Male 91 12 that higher menu items meant higher effort put into the creation.

Female 9 86 For instance a subject choosing item 40 was assumed to have

put more effort into their avatar than someone who chose item

5, as the first subject scrolled through more options to make

Table 8. Gender matches their choice. This measure is crude because it discounts the

possibility of a subject looking at a large number of options,

Match Mismatch

then navigating back to the first (the options had to be scrolled

Non-gamer 44 5

through in order—there was no short cut to jump to a particular

Gamer 74 9

one). The resulting measure was regressed as before. Overall

Frequent gamer 56 7

effort was not affected by gamer experience although effort in

‘getting dressed’ (choosing a top) was (Table 11).

Table 9. Counts of skin colour codes chosen by subjects for each This all suggests:

level of gamer experience

Result 4. No evidence has been found that experienced

Avatar

gamers are more or less likely than non-gamers to swap gender

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 in their avatar choice or to choose a particular skin colour

Non-gamer 1 4 3 10 18 1 8 4 0 for their avatar; there is weak evidence to suggest experienced

Gamer 1 6 2 17 30 12 12 2 1 gamers put more effort into their avatar appearance than non-

Frequent gamer 1 1 3 12 13 16 13 1 3 gamers.

Table 10. Counts of dark and pale skin colours chosen 5.4. World customization

by subjects for each level of gamer experience

Each user had a private apartment which they could customize

Avatar

(Fig. 4) by changing the style of the furniture and wallpaper,

Pale Dark and by putting up pictures, with the images taken from flickr.

Non-gamer 37 12 The number of changes each subject made to their apartment

Gamer 68 15 (excluding pictures), and the number of pictures they put up,

Frequent gamer 46 17 were regressed as before and were not found to be related to

gamer experience.

Interacting with Computers, 2013

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour 9

6. DISCUSSION and additional examinations of gamer chat to determine why

more real world references are made – is this because they

This project sent a pool of subjects with a range of gaming

do not need to be as focused on the virtual world than non-

experience into a virtual world that none of them had used

gamers, or are they more aware of their physical surroundings?

before. The world was a social networking space, of the sort

Further investigation should also examine what specifically it is

used for business meetings, training, collaboration and serious

about playing computer games that leads to these differences. In

games, as described in Section 1. This paper examined the

addition, if gamers chat more as leaders, does that mean gamers

hypothesis that gamers behave differently in such a virtual world

will make better team leaders in virtual worlds? An analysis of

than non-gamers. This is the first time that this research question

differences found between users of different ages would also

has been addressed. The literature summarized in Section 2

be useful. These are topical questions, especially given the the

suggested that the behaviours examined could all theoretically

literature reviewed in Section 2 that suggests virtual worlds have

have been influenced by gamer experience, but only some

a role to play in training. Lastly, further work could also re-

differences were found. Big differences were found in chat.

examine gamer/non-gamer clothing choices to confirm or refute

Much less distinct differences were found in movement and

the findings reported here.

avatar creation, and none were found in the customization of

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

the world. This is an interesting finding and suggests many

additional research questions which could be explored. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The quantitative chat analysis found that experienced gamers This research formed part of the VERUS project which was led

write more chat but not qualitatively different chat. The longer by John Murray at SRI International. The authors thank Don

sentences might be a function of experienced users’ comfort in Arns, Steve Benford, John Byrnes, Kyle Leveque, Immanuel

using in-game text chat, or it could be that non-gamers had to Moonesar, Said Muhammad, Allister Smeeton, Wen Wang

spend more effort focusing on other aspects of the world (such and the University of Wollongong, Dubai for their help, and

as navigation) meaning they were less able to attend to chatting. acknowledge research assistance from Natasha Ambigaibalan,

Customizing the world (such as decorating an apartment) is not Kasia Campbell and Lu Dong.

a feature found in many computer games and this may account

for the lack of difference here. Some evidence was found which

suggested experienced gamers put more effort into their avatar FUNDING

appearance than non-gamers but this was not strong and relied This project was funded by the U.S. Air Force Research Lab

on a crude metric. We found evidence that gamers will tend to under contract number FA8650-10-C-7009.

take on leadership roles, and communicate about the real world

more than non-gamers.

REFERENCES

Note that, if a number of statistical significance tests are

carried out, some are likely to give significant results even Ang, C.S., Zaphiris, P. and Mahmood, S. (2007) A model of cognitive

if all null hypotheses are true (Cumming, 2011). To deal loads in massively multiplayer online role playing games. Interact.

with this we examined our results again after a Bonferroni Comput., 19, 167–179.

correction was made to the P-value considered significant, and Bell, M. (2008) Toward a definition of “virtual worlds”. J. Virtual

our strongest results on chat (Results 1 and 2) still hold. As Worlds Res., 1.

for the other results, we report them as interesting findings Benford, S., Bowers, J., Fahlén, L.E., Greenhalgh, C. and Snowdon,

which future research can develop a comprehensive theoretical D. (1995) User Embodiment in CollaborativeVirtual Environments.

model of virtual world behaviour around. This is in line with, In Proc. ACM Conf. Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI,

for instance, Rothman (1990) who presents strong arguments pp. 242–249.

that any correction risks missing important findings and that a Bessière, K., Seay, A. and Kiesler, S. (2007) The ideal elf: identity

large number of tests is acceptable if any statistically significant exploration in world of warcraft. Cyberpsychol. Behav., 10, 530–

result is regarded as an interesting possibility needing further 535.

investigation, rather than an established finding. Bohannon, J. (2010) Smarts for serious games. Science, 330, 31.

Our findings have implications on the use of social

Chesney, T., Coyne, I., Logan, B. and Madden, N. (2009) Griefing

networking virtual worlds in contexts where users have a variety in virtual worlds: causes, casualties and coping strategies. Inform.

of backgrounds. The research highlights that there will be Syst. J., 19, 525–548.

differences in behaviour based on the experience that such

Chodos (2009) An integrated framework for simulation-based training

users have of computer games. It may be that such differences

on video and in a virtual world. J. Virtual Worlds Res., 2.

will disappear over time and future work should examine this.

That not all theoretically predicted differences were found Cumming, G. (2011) Understanding the New Statistics. Routledge.

also suggests avenues for further work. Possibilities include deNoyelles, A. and Seo, K.K.J. (2012) Inspiring equal contribution

repeating the data collection and analyses in different worlds and opportunity in a 3d multi-user virtual environment: bringing

Interacting with Computers, 2013

10 Thomas Chesney et al.

together men gamers and women non-gamers in second life. Messinger, P., Stroulia, E. and Lyons, K. (2008b) A typology of virtual

Comput. Educ., 58, 21–29. worlds: historical overview and future directions. J. Virtual Worlds

Dieterle, E. and Murray, J. (2010) Virtual Environment Real User Res., 1.

Study (VERUS): design and methodological considerations and Neuendorf, K. (2002) The Content Analysis Cookbook. Sage.

implications. J. Appl. Learn. Technol., 1, 19–25. Nowak, K. and Rauh, C. (2008) Choose your “buddy icon”

Donath, J. (2007) Virtually trustworthy. Science, 317, 53–54. carefully: the influence of avatar androgyny, anthropomorphism

Donovan, T. (2010) Replay. Yellow Ant. and credibility in online interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav., 24,

1473–1493.

Driver, E. and Jackson, P. (2008) Getting Real Work Done in Virtual

Worlds a Social Computing Report. Technical Report. Forrester. Richardson, A., Powers, M.E. and Bousquet, L. (2011) Video game

experience predicts virtual, but not real navigation performance.

Ducheneaut, N., Wen, M., Yee, N. and Wadley, G. (2009) Body and Comput. Hum. Behav., 27, 552–560.

mind: a study of avatar personalization in three virtual worlds. CHI

Proceedings, Boston, Massachusetts. Rossignol, J. (2005) Interview: evolution and risk: Ccp on the freedoms

of eve online.

Elo, S. and Kyngas, H. (2008) The qualitative content analysis process.

J. Adv. Nursing, 62, 107–115. Rothman, K. (1990) No adjustments are needed for multiple

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

comparisons. Epidemiology, 1, 43–46.

Frey, A., Hartig, J., Ketzel, A., Zinkernagel, A. and Moosbrugger, H.

(2007) The use of virtual environments based on a modification of Schrader, P. and McCreery, M. (2008) The acquisition of skill and

the computer game quake iii arena in psychological experimenting. expertise in massively multiplayer online games. Educ. Technol.

Comput. Hum. Behav., 23, 2026–2039. Res. Dev., 557–574.

Hafner, K. and Lyon, M. (1996) Where Wizzards Stay Up Late. Simon Schroeder, R. (1997) Networked worlds: social aspects of multi-user

& Schuster. virtual reality technology. Sociol. Res. Online, 2.

Hong, J. and Liu, M. (2003) A study on thinking strategy between Schroeder, R., Huxor, A. and Smith, A. (2001) Activeworlds:

experts and novices of computer games. Comput. Hum. Behav., geography and social interaction in virtual reality. Futures, 33, 569–

19, 245–258. 587.

Huffaker, D., Wang, J., Treem, J., Fullerton, L., Poole, M., Ahmad, Schultze, U. and Orlikowski, W. (2010) Virtual worlds: a performative

M., Williams, D. and Contractor, N. (2009) The Social Behaviors perspective on globally distributed, immersive work. Inform. Syst.

of Experts in Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games. Res., 21, 810–821.

In International Conference on Computational Science and Schultze, U. and Rennecker, J. (2007) Reframing Online Games:

Engineering, IEEE Computer Society. Synthetic Worlds as Media for Organizational Communication.

Jackson, R.L., Taylor, W. and Winn, W. (1999) Peer Collaboration International Federation for Information Processing, vol. 236, pp.

and Virtual Environments: a Preliminary Investigation of Multi- 335–351. Springer.

Participant Virtual Reality Applied in Science Education. Slater, M. and Steed, A. (2009) A virtual presence counter. Presence:

Proceedings of the 1999 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Teleoperators Virtual Environ., 9, 413–434.

ACM, New York, NY, USA. pp. 121–125. Slater, M., Sadagic,A., Usoh, M. and Schroeder, R. (2000) Small-group

Jung, Y. and Kang, H. (2010) User goals in social virtual worlds: behavior in a virtual and real environment. Presence: Teleoperators

a means-end chain approach. Comput. Hum. Behav., 26, 218–225. Virtual Environ., 9, 37–51.

Kagel, J. and Roth, A. (eds) (1995) The Handbook of Experimental Steinkuehler, C. (2004) A discourse analysis of mmog talk. In Sicart,

Economics. Princeton University Press. M. and Smith, J. (eds.) Other Players, Centre for Computer Games

Kirkpatrick, D. (2007) It’s not a game. Fortune, 155. Research, IT University of Copenhagen.

Landis, J.R. and Koch, G.G. (1977) The measurement of observer Taylor, T. (2002) Living digitally: embodiment in virtual worlds. The

agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174. Social Life of Avatars: Presence and Interaction in Shared Virtual

Environments, pp. 40–62. Springer.

Lomanowska, A. and Guitton, M. (2012) Spatial proximity to others

determines how humans inhabit virtual worlds. Comput. Hum. Taylor, T. (2003) Intentional bodies: virtual environments and the

Behav., 28, 318–323. designers who shape them. Int. J. Eng. Educ., 19, 25–34.

Martens, J. and Antonenko, P. (2012) Narrowing gender-based Taylor, T. (2008) Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives

performance gaps in virtual environment navigation. Comput. Hum. on Gender, Games and Computing. Becoming a player: networks,

Behav., 28, 809–819. structures and imagined futures. MIT Press.

Matsumoto,Y. and Thawonmas, R. (2004) Mmog Player Classification Taylor, N., de Castell, S., Jenson, J. and Humphrey, M. (2011)

using Hidden Markov Models. In Rauterberg, M. (ed.), ICEC, IFIP, Modelling Play: Re-Casting Expertise in mmogs. Proceedings of

pp. 429–434. the 20122 ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on Video Games, ACM,

New York, NY, USA, pp. 49–53.

Messinger, P., Ge, X., Stroulia, E., Lyons, K., Smirnov, K. and Bone,

M. (2008a) On the relationship between my avatar and myself. J. Terdiman, D., (2007) The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Second Life:

Virtual Worlds Res., 1. Making Money in the Metaverse. Wiley.

Interacting with Computers, 2013

A Study of Gamer Experience and Virtual World Behaviour 11

Trepte, S., Reinecke, L. and Behr, K. (2009) Creating virtual alter egos (iv) EVE Online. A virtual world with a science fiction

or superheroines? gamers’ strategies of avatar creation in terms setting. Until recently users have been represented

of gender and sex. Int. J. Gaming Comput.-Mediated Simul., 1, by a spaceship rather than a humanoid avatar. See:

52–76. www.eveonline.com

Turkle, S., (1995) Life on the screen: identity in the age of the Internet. (v) Everquest. A virtual world with a high fantasy setting.

Simon and Schuster. See: www.everquest.com

Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together. Basic Books. (vi) Football Manager. A soccer management game released

Verhagen, T., Feldberg, F., Hooff, B., Meents, S. and Merikivi, J. (2012)

in 1982. The soccer games themselves were not played

Understanding users’ motivations to engage in virtual worlds: a by the user who focussed solely on the management

multipurpose model and empirical testing. Comput. Hum. Behav., (player choices etc.) of their team.

28, 484–495. (vii) Gauntlet. An arcade game from Atari with a fantasy

Wang, W., Kathol, A. and Bratt, H. (2011) Automatic Detection

theme. Essentially a virtual world with only 4 players,

of Speaker Attributes based on Utterance Text. In Interspeech, the game never ended and the players’ goal was to keep

Florence, Italy. playing for as long as possible. Considered a classic

game, it is still popular can has been ported to several

Downloaded from http://iwc.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on July 24, 2013

Wasko, M., Teigland, R., Leidner, D. and Jarvenpaa, S. (2011) Stepping

into the internet: new ventures in virtual worlds. MIS Quart., 35,

modern platforms. See Donovan (2010).

645–652. (viii) Lineage. A Korean virtual world game with a medieval

fantasy setting.

Weber, A., Rufer-Bach, K. and Platel, R. (2007) Creating Your World:

(ix) Mafia Wars. A multiplayer social network game created

The Official Guide to Advanced Content Creation for Second Life.

Sybex.

by Zynga. See: www.mafiawars.com

(x) Maplestory. A free virtual world developed by South

Yee, N. and Bailenson, J. (2007) The proteus effect: the effect of Korean company Wizet with a low fantasy setting. See:

transformed self-representation on behavior. Hum. Commun. Res.,

maplestory.nexon.net

33, 271–290.

(xi) MUD. The original MUD or Multi-User Dungeon was

a multiplayer real-time virtual world described in text

and was heavily influenced by Colossal Cave Adventure

(Donovan, 2010).

(xii) Second Life. A general purpose virtual world developed

APPENDIX A. GAMES GLOSSARY

by Linden Lab. See: www.secondlife.com

(i) Colossal Cave Adventure. Designed by Will Crowther (xiii) Sonic the Hedgehog. A platform game developed by

and one of the first games to be available over Arpanet Sega.

(Hafner and Lyon, 1996), Colossal Cave Adventure was (xiv) Sudoko. A combinatorial number-placement puzzle.

the first text based adventure game. (xv) Tomb Raider. An influential action-adventure video

(ii) Doom. Developed by id Software, Doom used game developed by Core Design which used an

pioneering immersive 3D graphics and popularized innovative 3D third person perspective.

the first person shooter genre of games. See Donovan (xvi) Ultima Online. A virtual world game with a high fantasy

(2010). setting. See: www.uoherald.com

(iii) Elite. A single player trading game set in space and (xvii) World of Warcraft. A virtual world game with a high

released in 1984 known to have directly influenced the fantasy setting developed by Blizzard. See: www.world

MMOG Eve Online (Rossignol, 2005). ofwarcraft.com

Interacting with Computers, 2013

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Digital SelfDocument22 pagesDigital SelfGeorge Agnel100% (4)

- Introduction To Metaverse 1655720507Document41 pagesIntroduction To Metaverse 1655720507manjrekarnNo ratings yet

- Massively Multi Player Game DevelopmentDocument12 pagesMassively Multi Player Game Developmentbog20us100% (1)

- Extended Self in A Digital WorldDocument50 pagesExtended Self in A Digital WorldGirlene Lobaton Estrope0% (1)

- Liboriussen Samlet PDFDocument215 pagesLiboriussen Samlet PDFpiomorreoNo ratings yet

- Py Simple GUIDocument17 pagesPy Simple GUIJavier Matias Ruz Maluenda100% (2)

- The Immersive Artistic Experience and The Exploitation of Space-Bonnie MitchellDocument10 pagesThe Immersive Artistic Experience and The Exploitation of Space-Bonnie Mitchellmaal tsuNo ratings yet

- Serious Educational Game Assessment - Prac - Leonard Annetta, Stephen BronackDocument281 pagesSerious Educational Game Assessment - Prac - Leonard Annetta, Stephen BronackKo-Pe DefNo ratings yet

- Zhai - Get RealDocument232 pagesZhai - Get RealxmlbioxNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Northwind Database: CommentsDocument52 pagesIntroduction To The Northwind Database: CommentsAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Algorithm Database NormalizationDocument13 pagesAlgorithm Database NormalizationAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Springer TemplateDocument8 pagesSpringer TemplateAnonymous xAjD4l6No ratings yet

- Hotel ER DiagramDocument1 pageHotel ER DiagramAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Northwind Erd PDFDocument1 pageNorthwind Erd PDFJunnel FadrilanNo ratings yet

- Northwind Queries pt3Document4 pagesNorthwind Queries pt3AndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- NosqlDocument8 pagesNosqlAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- 14th International Conference On Information Technology: New Generations (ITNG 2017)Document16 pages14th International Conference On Information Technology: New Generations (ITNG 2017)AndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Modeling Relational Data As Graphs For MiningDocument6 pagesModeling Relational Data As Graphs For MiningAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Xiro Gian No PoulosDocument13 pagesXiro Gian No PoulosAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Red Black TreesDocument2 pagesRed Black TreesAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Tese IA e BDDocument106 pagesTese IA e BDAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Cormen Algo-Lec10Document29 pagesCormen Algo-Lec10geniusamitNo ratings yet

- Text Classification SVM PDFDocument7 pagesText Classification SVM PDFP6E7P7No ratings yet

- Lecture 5 - Text ClassificationDocument48 pagesLecture 5 - Text ClassificationAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Paper16 PDFDocument13 pagesPaper16 PDFAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Sample Solutions For 91.503 Assignment #1:) Log (LG) (LGDocument4 pagesSample Solutions For 91.503 Assignment #1:) Log (LG) (LGvittalisaNo ratings yet

- Insignias LOP MADocument1 pageInsignias LOP MAAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- A Genetic Algorithm For Database Query Optimization: February 1970Document9 pagesA Genetic Algorithm For Database Query Optimization: February 1970AndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Migration of Data From Relational Database To Graph DatabaseDocument6 pagesMigration of Data From Relational Database To Graph DatabaseAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Nver UsedDocument1 pageNver UsedAndersonOliveiraNo ratings yet

- Triumph of LifeDocument1 pageTriumph of LifeMickeymondeNo ratings yet

- Test Banks 7Document51 pagesTest Banks 7OsamaNo ratings yet

- 3D Internet Report - FinalDocument32 pages3D Internet Report - FinalAnthony Joseph0% (1)

- 2022-Affordances and Challenges of Teaching Language Skills by Virtual Reality - A Systematic Review (2010-2020)Document26 pages2022-Affordances and Challenges of Teaching Language Skills by Virtual Reality - A Systematic Review (2010-2020)JessicaEstevesNo ratings yet

- Turban Ec2012 PP 01 (Compatibility Mode)Document123 pagesTurban Ec2012 PP 01 (Compatibility Mode)Son HangNo ratings yet

- Realidad Virtual Queau FilosofiaDocument13 pagesRealidad Virtual Queau FilosofiaSara VegaNo ratings yet

- Mixed RealityDocument6 pagesMixed Realityatom tuxNo ratings yet

- The MagicBook A Transitional AR InterfaceDocument9 pagesThe MagicBook A Transitional AR InterfaceLeandro CarmeliniNo ratings yet

- Cyber EgoDocument8 pagesCyber Egoimanemin3mNo ratings yet

- MA, M. OIKONOMOU, A. Jain, L. C. (Eds.) - Serious Games and Edutainment ApplicationsDocument501 pagesMA, M. OIKONOMOU, A. Jain, L. C. (Eds.) - Serious Games and Edutainment ApplicationsLeonardo PassosNo ratings yet

- Virtual Reality and Education: By: Giti Javidi Submitted To: Dr. James White EME7938Document52 pagesVirtual Reality and Education: By: Giti Javidi Submitted To: Dr. James White EME7938yahelscribdNo ratings yet

- Virtual Reality ReportDocument24 pagesVirtual Reality Reportewanmcintyre9671No ratings yet

- The Metaverse What Are The Legal ImplicationsDocument8 pagesThe Metaverse What Are The Legal ImplicationsHarshithNo ratings yet

- E Learning in Health Education - Feasibility, Pros and Cons: S.HemalathaDocument18 pagesE Learning in Health Education - Feasibility, Pros and Cons: S.HemalathaHemalatha sNo ratings yet

- Transmedial Worlds - Rethinking Cyberworld Design: December 2004Document9 pagesTransmedial Worlds - Rethinking Cyberworld Design: December 2004orsi petrikNo ratings yet

- SOCIETYDocument23 pagesSOCIETYLuhan Albert YnarezNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Intersection - The Interplay of AI, Metaverse, Ethics, and Legal Dimensions - Edem BoniDocument2 pagesExploring The Intersection - The Interplay of AI, Metaverse, Ethics, and Legal Dimensions - Edem BoniEdem BoniNo ratings yet

- Ethnography in Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of MethodsDocument3 pagesEthnography in Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of MethodsGeoffrey TimberlakeNo ratings yet

- Aequitas Mixed Reality Exhibition On The Theme of ChildhoodDocument8 pagesAequitas Mixed Reality Exhibition On The Theme of ChildhoodStephen BeveridgeNo ratings yet

- Critical AnalysisDocument3 pagesCritical AnalysisjennypirotNo ratings yet

- MILQ3 Re 04182023Document4 pagesMILQ3 Re 04182023Reyshyl QuezonNo ratings yet

- Research DigitalDocument175 pagesResearch DigitalRhona ParasNo ratings yet