Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fluoride in Toothpastes For Children Suggestion For Change

Uploaded by

Liga Odontopediatria RondonienseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fluoride in Toothpastes For Children Suggestion For Change

Uploaded by

Liga Odontopediatria RondonienseCopyright:

Available Formats

PEDIATRICDENTISTRY/Copyright© 1988 by

The AmericanAcademy

of Pediatric Dentist~

Volume 10, Number

Fluoride in toothpastes for children: suggestion for change

Eugenio D. Beltr~n, DDS, MPH Susan M. Szpunar, MPH, DrPH

Abstract amounts of F from a number of sources, during the

dentition’s formative years. One potential source of

Fluoridatedtoothpastes weredesignedto producea topical

swallowed F is fluoridated toothpaste.

caries-preventive effect. Manystudies have showntheir effec-

tiveness. Recently, researchers have expressed concern that In many developed countries, F-containing tooth-

fluorosis may be increasing in the American population. pastes comprise 80-95%of all dentifrice sales (Dowell

Thereis speculationthat fluoride (F) from fluoridated tooth- 1981; Horowitz 1984). In the United States, the Ameri-

pastes might be a contributing factor whenthe toothpaste is can Dental Association publication, A Guide to the Use of

accidentallyswallowedby small children. Theobjective of this Fluorides, recommends the use of F dentifrices as soon as

paperis to evaluate the clinical and epidemiologicalevidence the first primary teeth erupt (ADA1986).

in regard to the relationship betweenthe swallowedfluoride The objective of this paper is to evaluate the evidence

from toothpaste andthe presenceof fluorosis. for a relationship between the swallowed F from tooth-

In regardto the epidemiologicalevidence,the reports in the paste and its potential effect on dental fluorosis.

literature showonly a slight increasein the fluorosis index in

communities that use fluoridated toothpastes with one or Evidence of Fluorosis

moretype of systemic fluoride. However,these are limited, not Although recent reviews (Heifetz and Horowitz

excluding studies. 1986; Szpunar and Burr 1987) have stressed the lack of

The concentration ofF in most toothpastes, 1000 ppm,is clear epidemiologic evidence showingan increase in the

a "best estimate", empirically derived rather than based on prevalence of fluorosis, some reports have pointed out

precisescientific study. the risk of fluorosis under simultaneous exposure of F

The clinical studies concerningingestion of toothpaste from multiple sources (Rozier and Dudney 1981;

showedthat children are ingesting between0.12 and 0.38 mg Ericsson and Ribelius 1971) including fluoridated den-

of toothpaste per brushing, which represents 0.12-0.38 mgF tifrices (Ekstrand and Ehrnebo 1980). However, very

for the 1.0 mgFig toothpastes. Childrenyoungerthan 3 years few controlled studies have addressed the issue of

of age maybe ingesting high levels of fluoride from tooth- dentifrices and fluorosis (Houwink and Wagg1979;

pastes. It wasclear that the risk of fluorosis increases when Holm and Anderson 1982).

children receive systemic fluoride~simultaneouslyfromdiffer-

ent sources. Ingestion and Retention of F ThroughToothpastes

It is concludedthat small children mayaccidentally swal- The literature showsindirect support for an F tooth-

low enoughfluoride to reachlevels consideredadequatefor the paste-fluorosis relationship. These studies analyze the

development.of fluorosis. Twoapproachesare recommended oral hygiene habits, amountof toothpaste used, and the

to reducethe hazardof fluorosis fromingested toothpastes:(1) amount of toothpaste ingested by infants and children.

manufactureof low-concentrationtoothpastes for children’s These data can be used to calculate with a certain degree

use; or (2) encourageparents to supervise children’s tooth- of confidencethe daily intake of F from toothpastes. It is

brushing using a small amountof toothpaste. also possible to calculate the amountof F received from

combined therapies.

It is generally accepted that the presence of fluoride Surveyed mothers reported children brushing with

(F) in the enamel, dental plaque, and saliva helps protect toothpaste, starting as young as 12 months, and swal-

teeth against carious attack. At the same time, there is lowing or even eating toothpaste directly from the tube

some concern that fluorosis may be increasing in Ameri- (Blinkhorn 1978; Dowell 1981).

can children as a result of ingestion of excessive

Pediatric Dentistry: September,1988~ Volume10, Number

3 185

The ingestion of toothpastes during toothbrushing is amounts of F if they follow the described pattern of

measured primarily by two methods: using a marker swallowing. Children who brush two or three times per

which is recovered from urine or feces (Barnhart et al. day clearly exceed these values. It is also clear that

1974); or subtracting the amount of toothpaste recov- children who either live in a community with fluori-

ered from the amount provided ([gravimetric] Har- dated drinking water or who receive dietary F supple-

greaves et al. 1972). The marker method tends to under- ments, and/or simultaneously ingest F from other

estimate the amount ingested if samples are not col- sources, are ingesting amounts of F that exceed

lected carefully and portends difficulties in the determi- Galagan’s optimal level. For example, Table 3 reports

nation of the tracer excreted (Barnhart et al. 1974). the theoretical values for combinedexposure to F tooth-

the other hand, the gravimetric approach tends to over- pastes and dietary F supplements under current recom-

estimate the values because any loss of toothpaste is mendations. Interestingly, the total amount of F expo-

recorded as being ingested (Baxter 1980). The "true" sure in this table attains and surpasses the values which

value probably lies between the values obtained by the were reported by Aasenden and Peebles (1978) as caus-

two methods (Hargreaves et al. 1972). ing fluorosis.

A review of the reports on ingestion of toothpaste It is important to note that not all the F ingested by

shows considerable variation ~ in the amount of tooth- fluoridated toothpastes is absorbed (Glass et al. 1975).

paste ingested (Ericsson and Forsman 1969; Hargreaves Although minimal interference between dentifrice and

et alo 1970, 1972; Nayloret al. 1971; Barnhart et al. 1974; abrasives is currently accepted (Forward 1980), it

Glass et al. 1975; Baxter 1980). Results maybe conflicting impossible to estimate to what extent the type of abra-

due to the different ages and methods used. What sive and the food already in the digestive tract affect F

appears to be a consistent pattern is the ingestion of absorption.

higher amounts of F at lower ages.

Someof these studies have pointed out inter- and Discussion

intrasubject changing patterns in brushing behavior The objective of any F preventive therapy is to attain

(Baxter 1980; Hargreaves et al. 1970, 1972; Naylor et al. the maximumanticaries benefit with minimumrisk of

1971). In addition, there appears to be no correlation fluorosis. For therapeutic purposes, it would be helpful

between the amount of toothpaste taken and the to have reliable information concerning the amountof F

amount swallowed (Hargreaves et al. 1972). Several a child needs for a given age or body weight (maximum

factors mayinfluence the amountof dentifrice used and effect). Unfortunately, this is not possible because of our

the amount retained; these include the length of the incomplete understanding of the cariostatic mecha-

toothbrush head, the diameter of the orifice of the tube nisms of F, and the many sources of F to which the

(Glass et al. 1975), the pleasant flavor of the dentifrices individual is exposed. On the other hand, there is no

(Baxter 1980), and most importantly, the ability of the sharp threshold for fluorosis (minimumrisk), and some

child to avoid swallowing. degree of fluorosis is considered esthetic or acceptable.

Clearly, our objective to attain maximumeffect with

Amountof Fluoride Swallowed from Toothpaste

a

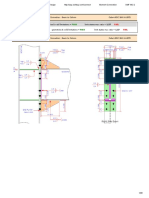

It is necessary to question whether the quantity of F TABLE 1o Theoretical Rangeof Fluoride Ingested from Toothpaste

obtained from toothpaste could be large enough to be a Numberof Toothbrushings per Day

risk factor for fluorosis. Dueto the variability of the data One Two Three

on dentifrice ingestion, minimumand maximumvalues

Amount b

0.12- 0.38 0.24- 0.76

of ingest6d toothpaste were selected from the reports in 0.36-1.14

fluoride

the literature. The selected values were: 0.12 (Ericsson

and Forsman1969) and 0.38 g (Hargreaves et al. 1972) In mgs of fluoride.

toothpaste/brushing which represent 0.12-0.38 mgof F From Ericsson and Forsman 1969 and Hargreaves et al. 1972, respectively.

per brushing for the 1 mgF/g toothpaste formulations TABLE 2. Theoretical Optimal Amountof Fluoride"

(Table 1).

Optimum Level

Age bWeight ~

of Fluoride

Total Amountof Fluoride Ingested

The comparison of these theoretical values with the 0-2 3.4-12.3 0.07-0.27

"optimal" levels of F (0.022 mg/kg) between birth and 2-3 12.3-13.4 0.27-0.29

3-6 13.4-21.1 0.29-0.46

6 years reported by Galagan et al. (1957, Table 2) indi-

cates that children whobrush their teeth once a day with Modified from Infante (1975) based on 0.022 mg/kg.

a fluoridated toothpaste might be ingesting optimal Mean weight in Kg for each age limit.

In mgs of fluoride.

186 FLUORIDEIN TOOTHPASTES

FORCHILDREN: BeJtr~n and Szpunar

TABLE

3. Theoretical Rangeof Children’s Fluoride Exposure" 1984). Moreover, Feigal (1983) and Ericsson

Forsman(1969) propose toothbrushing with a fluori-

Number

of Toothbrushings

per Day dated toothpaste only once a day. The recommenda-

bmgF One Two Three tion to use nonfluoridated toothpaste for the second

0-2 0.25 0.37- 0.63 0.49- 1.01 0.61- 1.39 or third toothbrushing (Feigal 1983) does not appear

2-3 0.50 0.62- 0.88 0.74- 1.26 0.88- 1.64 practical.

3-14 1.00 1.12-1.38 1.24-1.76 1.36- 2.14

Although these alternatives have been proposed for

Basedon the theoretical amountof fluoride ingested fromtoothpaste plus children who are exposed to optimally fluoridated

maximaldosageof daily fluoride supplementsfor 0.3 ppmF in the water water or dietary supplements, the evidence supports

supply.

Accordingto the schedulerecommended by the AmericanDental Associationthe extension of the recommendation for children re-

(1984) and the AmericanAcademyof Pediatrics (1986). ceiving F from toothpaste only.

It is recognized that small children mayaccidentally

minimumrisk is confronted with these inherent prob- swallow large enough amounts of fluoridated tooth-

lems. pastes to produce levels of F consumption associated

Fluoridated toothpastes were designed to produce a with an increased risk of developing fluorosis. To avoid

topical caries preventive effect. The efficacy of F denti- this hazard, the manufacture of low F concentration

frices has been demonstrated in many studies; two toothpastes, and parental instruction and supervision

excellent reviews include those of DePaola (1983) and of children’s toothbrushing, using a small amount of

Volpe (1982). The F concentration of American tooth- toothpaste, are recommended.It is interesting to note

pastes was established to provide 1.0 mg F for each that, contrary to these recommendations and the cur-

toothbrushing (American Dental Association 1986). rent interest in fluorosis, a fluoridated toothpaste that

Higher F formulations are not necessarily associated claims increased benefit recently has been introduced in

with increased benefit (Ripa et al. 1987). the market. This toothpaste contain 1.5 mg F/g, an

The present analysis shows that your~g children may increase of 50% over the actual ADA-recommended

be receiving amountsof F large enough to be considered concentration (ADA1984). The amount of F ingested

a risk for developing fluorosis specifically through the children would be increased by 50%if these dentifrices

accidental swallowing of fluoridated toothpaste. Many are used with the pattern described in this review.

researchers have expressed concern in this regard Finally, more research is necessary in the area of

(Forsman and Ericsson 1973; Glass et al. 1975; Houwink absorption of F from toothpastes, and in the epidemiol-

and Wagg 1979; Ekstrand and Ehrnebo 1980; Dowell ogy of fluorosis in populations receiving fluoridated

1981; Feigal 1983; Horowitz 1984). Theoretical values toothpastes alone or combinedwith other sources of F.

indicate that even if toothpaste is the only source of F,

children younger than 3 years of age still maybe ingest- Dr. Beltr~inis a doctoralstudent in dental public health at the

Universityof Michigan andDr. Szpunaris an epidemiologist at the

ing high levels of F from the dentifrice, dependingon the DentalDiseasePreventionActivity, Centersfor DiseaseControl,

pattern of swallowingand brushing. It is also clear that Atlanta,Georgia.Reprintrequestsshouldbe sent to: Dr. Eugenio D.

the risk of fluorosis increases when children receive F Beltr~n, Programof Dental Public Health, Dept. of Community

simultaneously from different sources. Yet, these values HealthPrograms,Schoolof Public Health,Universityof Michigan,

are based on assumptions that the behavior of children AnnArbor, MI48109-2029,

in toothpaste studies can be generalized and that the Aasenden R, PeeblesTC:Effects of fluoride supplementation from

entire amount of F ingested is retained. These assump- birth ondental caries and fluorosis in teenagedchildren. Arch

tions maynot be entirely valid. OralBiol23:111-15, 1978.

The following policy recommendations are pro- American

Dental AssociationCouncilof DentalTherapeutics:Ac-

posed: ceptedDentalTherapeutics.Chicago;1984pp 395-97,409-12.

1. Compoundfluoridated toothpaste with a lower. F American

DentalAssociation:

Aguideto the use of fluorides.J Am

content, package it in a box and tube color-coded and DentAssoc113:503-66,

1986.

with the label "for children’s use only." A potential

drawback is the possibility of reduced fluoridated American

Academy

of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition: Fluoride

supplementation.

Pediatrics77:758-61,1986.

toothpaste efficacy as shown by Forsman (1974) and

Mitropoulus et al. (1984). BarnhartWE,Hiller LK,LeonardGJ, MichaelsSE: Dentifriceusage

2. Direct parental toothbrushing instruction and/or and ingestion amongfour age groups. J DentRes 53:1317-22,

supervision. The use of a very small amount of 1974.

toothpaste should be stressed. This alternative has Baxter PM:Toothpasteingestion during toothbrushingby school

been recommended by many researchers (Horowitz children.Br DentJ 148:125-28,

1980.

Pediatric Dentistry: September,1988- VolumeI0, Number

3 187

BlinkhornAS: Influence of social normson toothbrushing behavior Heifetz SB, HorowitzHS: Amountsof fluoride in self-administered

of preschool children. CommunityDent Oral Epidemiol6:222-26, dental products: safety considerations for children. Pediatrics

1978. 77:876-81,1986.

DePaolaPF: Clinical studies of monofluorophosphatedentifrices. HolmAK,AnderssonR: Enamelmineralization disturbances in 12-

Caries Res 17:119-35,1981. year-old children with knownearly exposure to fluorides.

CommunityDent Oral Epidemiol 10:335-39, 1982.

DowellTB: The use of toothpaste in infancy. Br Dent J 150:247-49,

1981. HorowitzHS: Epidemiologyof fluorides, in Papers Submittedat the

Conference on Fluorides, Vienna 1982. Geneva; WorldHealth

Ekstrand J, EhrneboM: Absorptionof fluoride from fluoride denti- Organization pub ORH-82,1984.

frices. CariesRes 14:96-102,1980.

HouwinkB, WaggBJ: Effect of fluoride dentifrice usage during

Ericsson Y, Forsman B: Fluoride retained from mouthrinses and infancy uponenamelmottling of the permanentteeth. Caries Res

dentifrices in preschoolchildren. Caries Res 3:290-99,1969. 13:231-37,1979.

EricssonY, Ribelius U: Widevariations of fluoride supplyto infants Infante PF: Dietary fluoride intake from supplementsand communal

and their effect. Caries Res 5:78-88,1971. water supplies. AmJ Dis Child 129:835-37,1975.

Feigal RJ: Recentmodificationsin the use of fluorides for children. Mitropoulus CM, Holloway PJ, Davies TGH,Worthington HV:

NorthwestDent 62:19-21, 1983. Relative efficacy of dentifrices containing 250 or 1000ppmF in

preventing dental caries: report of a 32omonth clinical trial.

ForsmanB, Ericsson Y: Fluoride absorption from swallowedfluoride Community Dent Health 1:193-200, 1984.

toothpaste. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1:115-20, 1973.

Naylor MN,Melville M, Wilson RF, Ingram GS, WaggBJ: Ingestion

ForsmanB: Studies on the effect of dentifrices with low fluoride of dentifrice by youngchildren: a pilot study using a faecal

content. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2:166-75, 1974. marker(abstr). J DentRes 50:687, 1971.

Forward GC: Action and interaction of fluoride in dentifrices. Ripa LW,Leske GS,Sposato A, VarmaA: Clinical comparisonof the

CommunityDent Oral Epidemiol 8:257-66, 1980. caries inhibition of two mixedNaF-Na2PO3F dentifrices contain-

ing 1,000 and 2,500 ppmF comparedto a conventional Na2PO3F

GalaganDJ, Vermillion JR, Nevitt GA,Stadt ZM,Dart RE: Climate dentifrice containing1,000 ppmF: Results after two years. Caries

and fluid intake. Pub Health Rep 72:484-90, 1957. Res 21:149-57,1987.

Glass RL, Peterson JK, Zuckerberg DA,Naylor MN:Fluoride inges- Rozier RG, DudneyGG:Dental fluorosis in children exposed to

tion resulting fromthe use of monofluorophosphate

dentifrice by multiple sources of fluoride: implications for school fluoridation

children. Br DentJ 138:423-26,1975. programs. Pub Health Rep 96:542-46, 1981.

Hargreaves JA, Ingram GS, WaggBJ: A gravimetric study of the SzpunarSM,Burt BA:Trendsin the prevalenceof dental fluorosis in

ingestion of toothpaste by children. Caries Res 6:237-43,1972. the United States: a review. J Public HealthDent45:71-79,1987.

Hargreaves JA, Ingram GS, WaggBJ: Excretion studies on the VolpeAR:Dentifrices and mouthrinses, in A Textbookof Preventive

ingestion of a monofluorophosphatetoothpaste by children. Dentistry, 2nd ed. Stallard RE,ed. Philadelphia; WBSaundersCo,

Caries Res 4:256-68,1970. 1982pp 170-216.

Advertising dentists increase

Almost half of dentists participating in a recent survey are using some sort of advertising to promote

their practices to the public. The numbers of advertising dentists increased from similar studies

reported in the past.

Dentists new to practice are advertising more than established dentists. Two-thirds of the surveyed

dentists who have been in practice fewer than 5 years reported they use some form of advertising,

compared with half the dentists in practice 5-14 years; 32%of dentists in practice 15-24 years; and 30%

of dentists who have been practicing 25 years or more.

The most popular form of promotion was advertising in the Yellow Pages. ® Other methods

mentioned by survey respondents include: direct mail to attract new patients, newspaper ads,

Welcome Wagon, and coupons. Only 1% said they advertise their practices on radio or TV.

188 FLUORIDE

IN TOOTHPASTES

FORCHILDREN:

Beltran and Szpunar

You might also like

- The Rational Use of Fluoride ToothpasteDocument6 pagesThe Rational Use of Fluoride ToothpasteDeaa IndiraNo ratings yet

- Piis0002817714602269 PDFDocument2 pagesPiis0002817714602269 PDFdr stoicaNo ratings yet

- How Much Is A Pea-Sized Amount'? A Study of Dentifrice Dosing by Parents in Three CountriesDocument6 pagesHow Much Is A Pea-Sized Amount'? A Study of Dentifrice Dosing by Parents in Three CountriesBilly TrầnNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Intake of Children: Considerations For Dental Caries and Dental FluorosisDocument19 pagesFluoride Intake of Children: Considerations For Dental Caries and Dental FluorosisMara MHNo ratings yet

- Davies 2003Document6 pagesDavies 2003Angélica PortilloNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Use AAPDDocument2 pagesFluoride Use AAPDPanchusDa GamerNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Therapy: Latest RevisionDocument4 pagesFluoride Therapy: Latest RevisionLaura ZahariaNo ratings yet

- AAPD Policy on Use of FluorideDocument2 pagesAAPD Policy on Use of FluorideAlexandraPortugalInfantasNo ratings yet

- Dental FluorosisDocument5 pagesDental FluorosisLilianne SaidNo ratings yet

- Developmental Enamel Defects in Children With Different Fluoride Supplementation - A Follow-Up StudyDocument7 pagesDevelopmental Enamel Defects in Children With Different Fluoride Supplementation - A Follow-Up Studyandrea vargasNo ratings yet

- FLUORDocument2 pagesFLUORAna CristernaNo ratings yet

- P FluorideuseDocument2 pagesP FluorideuseSARA BUARISHNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0946672X21001668 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0946672X21001668 MainYaumil FauziahNo ratings yet

- 03 PDFDocument5 pages03 PDFayuNo ratings yet

- Guideline On Fluoride Therapy: Review Council Latest RevisionDocument4 pagesGuideline On Fluoride Therapy: Review Council Latest RevisionThesya Aulia GeovanyNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Controlled Trials On The Effectiveness of Fluoride Gels For The Prevention of Dental Caries in ChildrenDocument11 pagesSystematic Review of Controlled Trials On The Effectiveness of Fluoride Gels For The Prevention of Dental Caries in ChildrenJavangula Tripura PavitraNo ratings yet

- Preparing the tooth for a celluloid crown restorationDocument4 pagesPreparing the tooth for a celluloid crown restorationCristinaNo ratings yet

- Guide to Fluoride TherapyDocument4 pagesGuide to Fluoride TherapymirfanulhaqNo ratings yet

- G Fluoridetherapy PDFDocument4 pagesG Fluoridetherapy PDFChandrika VeerareddyNo ratings yet

- AAPD Policy On - FluorideUseDocument2 pagesAAPD Policy On - FluorideUsejinny1_0No ratings yet

- Fluoride: and Dental Caries Prevention in ChildrenDocument15 pagesFluoride: and Dental Caries Prevention in ChildrenTaufiq AlghofiqiNo ratings yet

- Terapia de Fluor AAPDDocument4 pagesTerapia de Fluor AAPDAndy HerreraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Dental Research: Topical Fluoride Therapy: Discussion of Some Aspects of Toxicology, Safety, and EfficacyDocument4 pagesJournal of Dental Research: Topical Fluoride Therapy: Discussion of Some Aspects of Toxicology, Safety, and EfficacyBob BobersonNo ratings yet

- Fluorides in Periodontal Therapy: A Review of the Benefits and ConsiderationsDocument4 pagesFluorides in Periodontal Therapy: A Review of the Benefits and ConsiderationsNurhikmah RnNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Toothpastes of Different Concentrations For Preventing Dental CariesDocument3 pagesFluoride Toothpastes of Different Concentrations For Preventing Dental CariesMarita JiménezNo ratings yet

- 8-Promoting Oral HealthDocument14 pages8-Promoting Oral HealthstardustpinaNo ratings yet

- JADA Fluoride 2014Document9 pagesJADA Fluoride 2014Víctor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Mouthrinses For Preventing Dental Caries in Children and AdolescentsDocument2 pagesFluoride Mouthrinses For Preventing Dental Caries in Children and AdolescentsRhena Fitria KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Infant Fluoride IntakeDocument1 pageInfant Fluoride IntakeCase Against FluorideNo ratings yet

- Effect of a School-based Fluoride Mouth-rinsing Programme on Dental CariesDocument6 pagesEffect of a School-based Fluoride Mouth-rinsing Programme on Dental CariesAishwarya AntalaNo ratings yet

- JDM 2018 004 Int@081-086Document6 pagesJDM 2018 004 Int@081-086Miguel Ángel De la Cruz GómezNo ratings yet

- A Review On ToothpasteDocument31 pagesA Review On ToothpastekhushalsharmadausaNo ratings yet

- BP FluorideTherapyDocument4 pagesBP FluorideTherapyKavana SrinivasNo ratings yet

- Wigen 2014Document9 pagesWigen 2014Johanna PinedaNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Toothpastes and Fluoride Mouthrinses For Home UseDocument11 pagesFluoride Toothpastes and Fluoride Mouthrinses For Home UsePînzariu GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Knowledge Among Texas DentistsDocument6 pagesFluoride Knowledge Among Texas Dentistscarmen mendo hernandezNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Care in ChildrenDocument2 pagesOral Health Care in ChildrenRaul GhiurcaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Sugar Xylitol Toothbrushing 20151126 20976 1j207nf With Cover Page v2Document9 pagesThe Role of Sugar Xylitol Toothbrushing 20151126 20976 1j207nf With Cover Page v2Arsalan Ahmed chakibNo ratings yet

- Dentists' Role in Preventing Tooth DecayDocument27 pagesDentists' Role in Preventing Tooth DecayMike Lawrence CadizNo ratings yet

- Bentley Et Al. Fluoride Ingestion From Toothpaste by Young Children. BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL, VOLUME 186, NO. 9, MAY 8 1999Document3 pagesBentley Et Al. Fluoride Ingestion From Toothpaste by Young Children. BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL, VOLUME 186, NO. 9, MAY 8 1999Ruth ZachariahNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Promotion and FluorideDocument42 pagesOral Health Promotion and FluorideZAWWIN HLAINGNo ratings yet

- Developmental Ages at LEH DevelopmentDocument11 pagesDevelopmental Ages at LEH DevelopmentKathrinaRodriguezNo ratings yet

- 5 Klasisifikasi ECCDocument3 pages5 Klasisifikasi ECCSusi AbidinNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Exposures and Dental Fluorosis A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesFluoride Exposures and Dental Fluorosis A Literature ReviewaflsnoxorNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Mechanisms of Dental Fluorosis in Man: Et Al.Document9 pagesThe Nature and Mechanisms of Dental Fluorosis in Man: Et Al.mageshwariNo ratings yet

- Research Paper FluorideDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Fluoridek0wyn0tykob3100% (1)

- Articulo 12.2 Fluor en Pastas DentalesDocument8 pagesArticulo 12.2 Fluor en Pastas DentalesLito UribarriNo ratings yet

- What Concentration of Fluoride Toothpaste Should Dental Teams Be RecommendingDocument2 pagesWhat Concentration of Fluoride Toothpaste Should Dental Teams Be RecommendingFărcășanu Maria-AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 2. Pastas DentalesDocument9 pagesArticulo 2. Pastas DentalesNORBILNo ratings yet

- Dental Uorosis: Exposure, Prevention and Management: ArticleDocument6 pagesDental Uorosis: Exposure, Prevention and Management: ArticlealyssaNo ratings yet

- CDA Supports Fluoride Use in Preventing Tooth DecayDocument5 pagesCDA Supports Fluoride Use in Preventing Tooth DecayJo Ker PuddinNo ratings yet

- Pasta de Dietes TratamientoDocument6 pagesPasta de Dietes TratamientoIsabel MelenoNo ratings yet

- Dental Fluorosis Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesDental Fluorosis Literature Reviewc5m07hh9100% (1)

- 1724-Article Text-4783-1-10-20200716Document9 pages1724-Article Text-4783-1-10-20200716ALdy AmbaritaNo ratings yet

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health Oral Health Program P. O. Box 2659 Madison, WI 53701-2659Document2 pagesWisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health Oral Health Program P. O. Box 2659 Madison, WI 53701-2659Foysal SirazeeNo ratings yet

- Basic Oral Care for Patients With DysphagiaDocument9 pagesBasic Oral Care for Patients With DysphagiaAngélica GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Remineralization, The Natural Caries Repair Process-The Need For New ApproachesDocument4 pagesRemineralization, The Natural Caries Repair Process-The Need For New ApproachesKranti PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Thiessen Fluoridation Comments 09-2013Document27 pagesThiessen Fluoridation Comments 09-2013Case Against FluorideNo ratings yet

- 50 Reasons to Oppose FluoridationDocument27 pages50 Reasons to Oppose FluoridationenitrebuaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Restorative DentistryFrom EverandPediatric Restorative DentistrySoraya Coelho LealNo ratings yet

- OzoneDocument6 pagesOzoneLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Ozoneseminar 171027190215Document60 pagesOzoneseminar 171027190215Liga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of The Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Healozone For The Treatment of Occlusal Pit/Fissure Caries and Root CariesDocument100 pagesSystematic Review of The Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Healozone For The Treatment of Occlusal Pit/Fissure Caries and Root CariesLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Ispub 14162Document7 pagesIspub 14162Liga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Dent05 p0393Document7 pagesDent05 p0393Liga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Yanagawa, H. 2001 PDFDocument6 pagesYanagawa, H. 2001 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Newburger, J. W. 2000 PDFDocument4 pagesNewburger, J. W. 2000 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- NEWBURGER, J. W. Et Al. 1991 PDFDocument7 pagesNEWBURGER, J. W. Et Al. 1991 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- VINCENT P. Et Al. 2007 PDFDocument3 pagesVINCENT P. Et Al. 2007 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Dentistry in AirDocument3 pagesDentistry in AirSyafri Papanya Syauqi ArdanNo ratings yet

- NAKAMURA, Y. Et Al. 2008 PDFDocument6 pagesNAKAMURA, Y. Et Al. 2008 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Senzaki, H. 2008 PDFDocument11 pagesSenzaki, H. 2008 PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Fluoride Dentifrices To TheDocument8 pagesThe Importance of Fluoride Dentifrices To TheLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Barodontalgia: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument5 pagesPathophysiology of Barodontalgia: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Dental Barotrauma in French Military Divers: Results of The POP StudyDocument5 pagesDental Barotrauma in French Military Divers: Results of The POP StudyLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Barodontalgia A Diagnostic Dilema in The Dental PainDocument5 pagesBarodontalgia A Diagnostic Dilema in The Dental PainLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Frnquecyobarodontalgia PDFDocument6 pagesFrnquecyobarodontalgia PDFLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Toothpastes Compos I To inDocument54 pagesToothpastes Compos I To inLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- New Zealand Guidelines GroupDocument2 pagesNew Zealand Guidelines GroupLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Fluoride Toothpastes For Preventing Dental Caries in ChildrenDocument108 pagesFluoride Toothpastes For Preventing Dental Caries in ChildrenLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Maxillary Canines Agenesis: A Case Report and A Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesBilateral Maxillary Canines Agenesis: A Case Report and A Literature ReviewLiga Odontopediatria Rondoniense100% (1)

- 121 02Document11 pages121 02Hiroj BagdeNo ratings yet

- Fluour e Seus NegociosDocument8 pagesFluour e Seus NegociosLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Choice of Toothpaste For The ElderlyDocument7 pagesChoice of Toothpaste For The ElderlyLiga Odontopediatria RondonienseNo ratings yet

- Omega: Mahdi Alinaghian, Nadia ShokouhiDocument15 pagesOmega: Mahdi Alinaghian, Nadia ShokouhiMohcine ES-SADQINo ratings yet

- Berkowitz Et Al (2010) - Skills For Psychological Recovery - Field Operations GuideDocument154 pagesBerkowitz Et Al (2010) - Skills For Psychological Recovery - Field Operations GuideRita CamiloNo ratings yet

- Group ActDocument3 pagesGroup ActRey Visitacion MolinaNo ratings yet

- Quality Control and Quality AssuranceDocument7 pagesQuality Control and Quality AssuranceMoeen Khan Risaldar100% (1)

- Challenges Faced by Irregular StudentsDocument13 pagesChallenges Faced by Irregular StudentsTicag Teo80% (5)

- Method Overloading in JavaDocument6 pagesMethod Overloading in JavaPrerna GourNo ratings yet

- Self-Sustainable Village: Dharm Raj Jangid 16031AA015Document2 pagesSelf-Sustainable Village: Dharm Raj Jangid 16031AA015Dharm JangidNo ratings yet

- Avelino Vs Cuenco (Case Digest)Document8 pagesAvelino Vs Cuenco (Case Digest)Christopher Dale WeigelNo ratings yet

- AllareDocument16 pagesAllareGyaniNo ratings yet

- Advanced Guide To Digital MarketingDocument43 pagesAdvanced Guide To Digital MarketingArpan KarNo ratings yet

- PTR01 21050 90inst PDFDocument40 pagesPTR01 21050 90inst PDFЯн ПавловецNo ratings yet

- THC124 - Lesson 1. The Impacts of TourismDocument50 pagesTHC124 - Lesson 1. The Impacts of TourismAnne Letrondo Bajarias100% (1)

- Man 400eDocument324 pagesMan 400eLopez Tonny100% (1)

- Result Summary - Overall: Moment Connection - Beam To Column Code AISC 360-16 LRFDDocument29 pagesResult Summary - Overall: Moment Connection - Beam To Column Code AISC 360-16 LRFDYash Suthar100% (2)

- Kiro Urdin BookDocument189 pagesKiro Urdin BookDane BrdarskiNo ratings yet

- Development PlanningDocument15 pagesDevelopment PlanningSamuelNo ratings yet

- PW 160-Taliban Fragmentation Fact Fiction and Future-PwDocument28 pagesPW 160-Taliban Fragmentation Fact Fiction and Future-Pwrickyricardo1922No ratings yet

- Sliding Sleeves Catalog Evolution Oil ToolsDocument35 pagesSliding Sleeves Catalog Evolution Oil ToolsEvolution Oil Tools100% (1)

- NYC Chocolate Chip Cookies! - Jane's PatisserieDocument2 pagesNYC Chocolate Chip Cookies! - Jane's PatisserieCharmaine IlaoNo ratings yet

- DP-10/DP-10T/DP-11/DP-15/DP-18 Digital Ultrasonic Diagnostic Imaging SystemDocument213 pagesDP-10/DP-10T/DP-11/DP-15/DP-18 Digital Ultrasonic Diagnostic Imaging SystemDaniel JuarezNo ratings yet

- Data Structures and Algorithms in Java ™: Sixth EditionDocument8 pagesData Structures and Algorithms in Java ™: Sixth EditionIván Bartulin Ortiz0% (1)

- DownloadDocument2 pagesDownloadAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- Project management software enables collaborationDocument4 pagesProject management software enables collaborationNoman AliNo ratings yet

- (Jean Oliver and Alison Middleditch (Auth.) ) Funct (B-Ok - CC)Document332 pages(Jean Oliver and Alison Middleditch (Auth.) ) Funct (B-Ok - CC)Lorena BurdujocNo ratings yet

- String inverter comparisonDocument4 pagesString inverter comparisonRakesh HateyNo ratings yet

- The Korean MiracleDocument20 pagesThe Korean MiracleDivya GirishNo ratings yet

- Slide Detail For SCADADocument20 pagesSlide Detail For SCADAhakimNo ratings yet

- GeM Bidding 3702669Document10 pagesGeM Bidding 3702669ANIMESH JAINNo ratings yet

- Sop For FatDocument6 pagesSop For Fatahmed ismailNo ratings yet

- Cell Organelles 11Document32 pagesCell Organelles 11Mamalumpong NnekaNo ratings yet