Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 1002@bjs 9867 PDF

10 1002@bjs 9867 PDF

Uploaded by

Nitish AggarwalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10 1002@bjs 9867 PDF

10 1002@bjs 9867 PDF

Uploaded by

Nitish AggarwalCopyright:

Available Formats

Randomized clinical trial

Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial of conventional

surgery, endovenous laser ablation and ultrasound-guided foam

sclerotherapy in patients with great saphenous varicose veins

S. K. van der Velden1 , A. A. M. Biemans2 , M. G. R. De Maeseneer1,4 , M. A. Kockaert1 ,

P. W. Cuypers3 , L. M. Hollestein1 , H. A. M. Neumann1 , T. Nijsten1 and R. R. van den Bos1

Departments of Dermatology, 1 Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, and 2 Elisabeth-Twee Steden Hospital, Tilburg, and 3 Department of

Vascular Surgery, Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, and 4 Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp,

Belgium

Correspondence to: Dr S. K. van der Velden, Department of Dermatology, Erasmus MC, Burgemeester s’ Jacobplein 51, 3015 CA, Rotterdam,

The Netherlands (e-mail: s.vandervelden@erasmusmc.nl)

Background: A variety of techniques exist for the treatment of patients with great saphenous vein (GSV)

varicosities. Few data exist on the long-term outcomes of these interventions.

Methods: Patients undergoing conventional surgery, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and ultrasound-

guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) for GSV varicose veins were followed up for 5 years. Primary outcome

was obliteration or absence of the treated GSV segment; secondary outcomes were absence of GSV reflux,

and change in Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality-of-life Questionnaire (CIVIQ) and EuroQol – 5D

(EQ-5D™) scores.

Results: A total of 224 legs were included (69 conventional surgery, 78 EVLA, 77 UGFS), 193 (86⋅2 per

cent) of which were evaluated at final follow-up. At 5 years, Kaplan–Meier estimates of obliteration or

absence of the GSV were 85 (95 per cent c.i. 75 to 92), 77 (66 to 86) and 23 (14 to 33) per cent in the

conventional surgery, EVLA and UGFS groups respectively. Absence of above-knee GSV reflux was found

in 85 (73 to 92), 82 (72 to 90) and 41 (30 to 53) per cent respectively. CIVIQ scores deteriorated over time

in patients in the UGFS group (0⋅98 increase per year, 95 per cent c.i. 0⋅16 to 1⋅79), and were significantly

worse than those in the EVLA group (−0⋅44 decrease per year, 95 per cent c.i. −1⋅22 to 0⋅35) (P = 0⋅013).

CIVIQ scores for the conventional surgery group did not differ from those in the EVLA and UGFS groups

(0⋅44 increase per year, 95 per cent c.i. −0⋅41 to 1⋅29). EQ-5D™ scores improved equally in all groups.

Conclusion: EVLA and conventional surgery were more effective than UGFS in obliterating the GSV

5 years after intervention. UGFS was associated with substantial rates of GSV reflux and inferior

CIVIQ scores compared with EVLA and conventional surgery. Registration number: NCT00529672

(http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Paper accepted 7 May 2015

Published online 1 July 2015 in Wiley Online Library (www.bjs.co.uk). DOI: 10.1002/bjs.9867

Introduction follow-up. Several long-term prospective case series have

been published4 – 6 reporting success rates for conventional

Many treatment options are available for patients with surgery, EVTA and UGFS of up to 94, 90 and 58 per cent

symptomatic reflux of the great (GSV) or small (SSV) respectively. High-quality data are sparse and, to date,

saphenous vein. They include endovenous thermal the results of only two randomized clinical trials (RCTs)

ablation (EVTA) with laser, radiofrequency or steam, have been published7,8 , showing similar recurrence rates

ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), and after conventional surgery and endovenous laser ablation

conventional surgery. Current guidelines1 – 3 , which rec- (EVLA) of the GSV, with follow-up of 5 years.

ommend EVTA as the treatment of choice for a refluxing The objective of the present study was to compare

saphenous vein, are based largely on studies with short- long-term outcomes of conventional surgery, EVLA and

or mid-term follow-up. However, the high recurrence UGFS 5 years after the intervention. The 1-year results of

rates of varicose veins emphasize the need for long-term this trial have been reported previously9 .

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Treatment of great saphenous varicose veins 1185

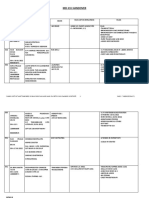

Legs allocated randomly to

treatment groups n = 240

Allocated to conventional surgery n = 80 Allocated to EVLA n = 80 Allocated to UGFs n = 80

Received intervention n = 65 Received intervention n = 76 Received intervention n = 77

Did not receive intervention n = 15 Did not receive intervention n = 4 Did not receive intervention n = 3

Did not fulfil inclusion criteria n = 8 Did not fulfil inclusion criteria n = 1 Did not fulfil inclusion criteria n = 1

Withdrew from study n = 2 Technical failure¤ n = 2 Withdrew from study n = 2

Received other intervention∗ n = 3 Received other intervention§ n = 1

Technical failure£ n = 2

Available for follow-up n = 69 Available for follow-up n = 78 Available for follow-up n = 77

Discontinued follow-up n = 6 Discontinued follow-up n = 15 Discontinued follow-up n = 10

Died n = 3 Died n = 1 Died n = 5

Refused or unavailable for follow-up n = 3 Moved n = 3 Moved n = 1

Refused or unavailable for follow-up n = 11 Refused or unavailable for follow-up n = 4

Analysed n = 69 Analysed n = 78 Analysed n = 77

For primary outcome n = 69 For primary outcome n = 78 For primary outcome n = 77

For secondary outcomes¶ n = 63 For secondary outcomes# n = 63 For secondary outcomes∗∗ n = 67

For HRQoL outcomes n = 52 For HRQoL outcomes n = 62 For HRQoL outcomes n = 59

Fig. 1CONSORT diagram for the trial. *One patient was treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and two patients were treated

with ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS); †patients received ligation only; ‡patients received UGFS instead; §patient

received RFA. For secondary outcomes, presence of saphenofemoral reflux, grades of neovascularization and number of additional

treatments were analysed using the χ2 test in 63, 63 and 67 limbs in the conventional surgery, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and

UGFS groups respectively. Absence of great saphenous vein reflux, presence of neovascularization, clinical class, progression of disease,

number of reinterventions and additional treatments were analysed in ¶69, #78 and **77 limbs using Kaplan–Meier and linear

mixed-effect models. For health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes, Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality-of-life Questionnaire

(CIVIQ), EuroQol – 5D (EQ-5D™) and visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) scores were analysed in 52, 62 and 59 patients using linear

mixed-effect models. Patients with bilateral treatment were excluded from HRQoL analyses

Methods patients with saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) reflux (from

either the terminal or preterminal valve) and a refluxing

Patients were enrolled in a multicentre, non-blinded,

GSV above the knee with a diameter of at least 5 mm

randomized, three-arm, parallel-group trial at the

(measured mid-thigh) were included. Reflux was defined

Departments of Dermatology and Vascular Surgery of

as retrograde flow during more than 0⋅5 s after calf com-

two centres (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, and Catharina

pression. Bilateral inclusion was allowed and each leg was

Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The trial was

randomized separately. Exclusion criteria were previous

approved by the research ethics committee at Erasmus

treatment of ipsilateral GSV, post-thrombotic syndrome,

MC (MEC2005-325). The study design, procedures and

agenesis of the deep venous system, vascular malforma-

1-year outcomes (primary endpoint) have been reported

tions, use of anticoagulant treatment, pregnancy, heart

previously9 . This cohort includes patients who were fol-

failure, known allergy to local anaesthetics or sclerosing

lowed up for up to 5 years postintervention. Details of

agents, immobility, arterial disease (ankle : brachial pres-

the study protocol are available at www.clinicaltrials.gov

sure index of less than 0⋅6), age under 18 years and inability

(registration number NCT00529672).

to provide written informed consent.

In brief, consecutive patients presenting between Jan-

uary 2007 and December 2009 with lower-limb venous

symptoms, after routine screening by means of medical

Concealment of allocation

history, clinical examination (defining the clinical class C of

the CEAP (Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic) Eligible limbs of patients who had given written informed

classification)10 and duplex ultrasound imaging, were consent were randomized in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to receive

invited to participate in the trial. Only symptomatic EVLA, UGFS or conventional surgery. Treatments were

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1186 S. K. van der Velden, A. A. M. Biemans, M. G. R. De Maeseneer, M. A. Kockaert, P. W. Cuypers, L. M. Hollestein et al.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients and legs available for follow-up

Conventional surgery EVLA UGFS

Patients n = 65 n = 70 n = 64

Age (years)* 52⋅5(15⋅6) 50⋅2(14⋅6) 56⋅4(13⋅5)

Sex ratio (F : M) 45 : 20 49 : 21 44 : 20

CIVIQ score* 24⋅1(19⋅1) 25⋅7(21⋅2) 25⋅2(19⋅2)

EQ-5D™*

Descriptive 0⋅9(0⋅1) 0⋅9(0⋅2) 0⋅8(0⋅2)

EQ VAS 79⋅0(12⋅8) 79⋅5(14⋅9) 78⋅7(13⋅4)

Legs n = 69 n = 78 n = 77

No. of legs

Left side 35 (51) 48 (62) 46 (60)

Right side 34 (49) 30 (38) 31 (40)

Unilateral or bilateral treatment

Unilateral 52 (75) 62 (79) 59 (77)

Bilateral (same treatment for both legs) 8 (12) 6 (8) 10 (13)

Bilateral (other treatment in contralateral leg) 9 (13) 10 (13) 8 (10)

GSV diameter (mm)* 6⋅2(1⋅5) 6⋅4(1⋅4) 6⋅1(1⋅4)

Clinical class

C1 1 (1) 0 (0) 1 (1)

C2 32 (46) 37 (47) 34 (44)

C3 21 (30) 29 (37) 30 (39)

C4 14 (20) 8 (10) 8 (10)

C5 1 (1) 0 (0) 1 (1)

C6 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Missing 0 (0) 4 (5) 3 (4)

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; *values are mean(s.d.). EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided

foam sclerotherapy; CIVIQ, Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality-of-life Questionnaire; EQ-5D™, EuroQol – 5D; VAS, visual analogue scale; GSV,

great saphenous vein.

assigned using blocks with a size of six by an independent was determined by the length and diameter of the vein, with

research nurse at Erasmus MC. Both participating hospi- a maximum of 10 ml per session. Refluxing tributaries were

tals offered the three treatment options. not treated systematically at the time of UGFS, but only in

case of complaints. If considered necessary, UGFS of the

GSV was repeated once between 3 months and 1 year after

Treatment methods

the initial treatment.

Conventional surgery consisted of high ligation at the SFJ At the end of all treatments, a compression bandage

and closure of the cribriform fascia, followed by invaginat- was applied. After 48 h, the bandage was replaced by

ing stripping of the above-knee GSV and phlebectomies of a medical elastic compression stocking (ankle pressure

varicose tributaries. All conventional surgery interventions 23–32 mmHg) for 2 weeks during the day.

were performed under spinal or general anaesthesia. Fully trained staff surgeons performed conventional

EVLA was performed under local tumescent anaesthe- surgery or EVLA procedures. EVLA was also performed

sia with a 940-nm diode laser. The refluxing GSV was by fully trained dermatologists and by dermatology

entered at knee level under ultrasound guidance, and the trainees, who were supervised by fully trained staff der-

tip of the laser fibre was positioned 1–2 cm from the SFJ. A matologists. UGFS was performed only by fully trained

bare-tipped fibre was used in all patients. Tumescent anaes- dermatologists and dermatology trainees, supervised by

thesia was administered under ultrasound guidance and the the same dermatologists.

sheath with the laser fibre was pulled back continuously

at a rate corresponding to 60 J per cm vein (power setting

Outcomes and follow-up protocol

10 W). Tributaries were removed by phlebectomies, con-

comitantly or in a subsequent session. Outcomes were evaluated at 3 and 12 months, and yearly

For UGFS, foam was prepared using the Tessari method thereafter. The primary outcome measure was obliter-

with 1 ml of 3 per cent polidocanol and 3 ml air11 . The ation or absence of the treated part of the GSV 5 years

refluxing GSV was injected directly at the level of the knee after treatment. Duplex ultrasound findings of the treated

under ultrasound guidance. The volume of injected foam GSV were categorized as follows: completely open with

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Treatment of great saphenous varicose veins 1187

1·0 1·0

Probability of absence of above-knee GSV reflux

0·8 0·8

Probability of obliterated GSVs

0·6 0·6

0·4 0·4

CS CS

EVLA EVLA

UGFS UGFS

0·2 0·2

0 1 2 3 4 5 0 1 2 3 4 5

Time after treatment (years) Time after treatment (years)

No. at risk No. at risk

CS 69 61 60 57 54 24 CS 69 64 61 58 55 25

EVLA 78 64 60 54 51 29 EVLA 78 66 61 57 55 31

UGFS 77 52 40 32 26 13 UGFS 77 59 46 39 33 18

Fig. 2Freedom from recanalization after conventional surgery Fig. 3Freedom from above-knee great saphenous vein (GSV)

(CS), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and ultrasound-guided reflux after conventional surgery (CS), endovenous laser ablation

foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) for great saphenous vein (GSV) (EVLA) and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) for

varicose veins. P < 0⋅001 (log rank test) great saphenous varicose veins. P < 0⋅001 (log rank test)

reflux (category 1); partial or segmental obliteration Neovascularization was defined as the presence of small

with reflux (category 2); partial or segmental oblitera- or larger tortuous veins between the saphenous stump or

tion with antegrade flow (category 3); total obliteration common femoral vein and superficial veins. Neovascular-

or absence (category 4)12 . For the primary outcome, ization was classified into two grades. Grade I was defined

only patients in category 4 were considered to have as tiny veins with a diameter smaller than 4 mm, limited to

had anatomical treatment success. Follow-up duplex the groin area. Grade II (clinically relevant) was defined as

ultrasonography was performed by vascular technol- larger tortuous refluxing veins (diameter of at least 4 mm)

ogists supervised by experienced vascular surgeons, at the SFJ directly connecting with refluxing tributaries at

or by dermatology trainees supervised by experienced thigh level, a residual refluxing part of the GSV or anterior

dermatologists. accessory saphenous vein (AASV)15 .

Secondary outcomes included absence of above-knee New refluxing tributaries of the GSV or AASV above

GSV reflux (categories 3 and 4), disease-specific and or below the knee, appearing after more than 2 years of

generic health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) scores, follow-up, were considered as progression of venous dis-

class C, SFJ reflux, presence of neovascularization at ease. Reinterventions of the GSV above knee level, and

the SFJ, progression of venous disease and number of additional treatments of the AASV, GSV below knee level,

reinterventions or additional treatments. and tributaries above and below knee level, were recorded

Disease-specific HRQoL scores were measured using in patients’ files between 1 and 5 years of follow-up. In

the Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality-of-life Question- patients with symptoms, reintervention or additional treat-

naire (CIVIQ)13 , and generic HRQoL scores were mea- ment was performed.

sured using EuroQol – 5D (EQ-5D™; EuroQol Group,

Rotterdam, The Netherlands)14 . The latter consists of two

Statistical analysis

separate summarizing scores: EQ visual analogue scale (EQ

VAS) and descriptive system (EQ-5D). Data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. Con-

The SFJ was checked for the presence or absence of tinuous variables were normally distributed and compared

reflux and for neovascularization on duplex imaging12 . by one-way ANOVA. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1188 S. K. van der Velden, A. A. M. Biemans, M. G. R. De Maeseneer, M. A. Kockaert, P. W. Cuypers, L. M. Hollestein et al.

25 25 25 Deteriorated

HRQoL

CIVIQ score

CIVIQ score

CIVIQ score

20 20 20

Improved

15 15 15 HRQoL

10 10 10

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

Time after treatment (years) Time after treatment (years) Time after treatment (years)

a Conventional surgery b EVLA c UGFS

Fig. 4 Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality-of-life Questionnaire (CIVIQ) scores with 95 per cent c.i. in the 5 years after a conventional

surgery, b endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and c ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) for great saphenous varicose veins.

HRQoL, health-related quality of life. Changes in scores for conventional surgery and EVLA were small and non-significant, whereas

those for UGFS were significantly different compared with values in the EVLA group (P = 0⋅013, linear mixed-effect model). Table 2

shows regression coefficients for the different CIVIQ scores

estimate survival free from GSV recanalization (categories primary GSV reflux were randomly allocated to conven-

1–3), reflux (categories 1 and 2) or neovascularization. tional surgery, EVLA or UGFS (Fig. 1). In total, 193 (86⋅2

Restricted mean survival time (RMST) ratios were cal- per cent) of 224 treated legs (170 patients) were evaluated

culated, representing the ratio between the mean survival at 5-year follow-up (median length of follow-up 4⋅8 years).

time during a restricted follow-up period (5 years) of two Demographic data, class C, GSV diameter and HRQoL

groups16 . impairment were similar among the three groups (Table 1),

Measurements over time were analysed using a lin- but patients undergoing EVLA were slightly younger

ear mixed-effect model. For each outcome the best fit- (50⋅2 years versus 52⋅5 and 56⋅4 years in conventional

ted model was used (random intercept, random intercept surgery and UGFS groups respectively; P = 0⋅048).

and slope, random intercept and slope and non-linear Legs in the EVLA group received a mean(s.d.) of

terms). The main analysis included no co-variables. Age 59⋅2(15⋅2) J/cm. In the UGFS group, the total mean(s.d.)

was included as a co-variable in the multivariable analysis. volume of injected foam was 4⋅4(2⋅1) ml.

Patients who had both legs randomized were excluded

completely from the HRQoL analyses.

Primary outcome

Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s

exact test. The Bonferroni test was used to correct for Anatomical treatment success (category 4)

multiple testing. Class C and progression of disease were At 5 years after intervention, the treated GSV was com-

analysed using a proportional odds mixed-effect model pletely obliterated or absent in 85 (95 per cent c.i. 75 to

(random slope with random intercept). 92) per cent of legs in the conventional surgery group, 77

SPSS® version 21.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New (66 to 86) per cent in the EVLA group and 23 (14 to 33) per

York, USA) was used for data analysis. Mixed-effect cent in the UGFS group (P < 0⋅001) (Fig. 2). Four patients

model analyses were conducted using available software in the conventional surgery group received high ligation or

(http://www.r-project.org). UGFS rather than the planned intervention (Fig. 1).

Patients treated with conventional surgery or EVLA were

Results four times more likely to have persisting obliteration of

the above-knee GSV than patients in the UGFS group at

A total of 840 patients with varicose veins attending the trial 5 years (UGFS/EVLA RMST ratio: 0⋅6, 95 per cent c.i. 0⋅5

centres were assessed for eligibility between January 2007 to 0⋅8; UGFS/conventional surgery RMST ratio: 0⋅6, 0⋅5

and December 2009. Some 240 legs (223 patients) with to 0⋅7).

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Treatment of great saphenous varicose veins 1189

Table 2 Regression coefficients of CIVIQ and EQ-5D™ scores in the three treatment groups

Conventional surgery (n = 52) EVLA (n = 62) UGFS (n = 59)

CIVIQ score 0⋅44 (−0⋅41, 1⋅29) −0⋅44 (−1⋅22, 0⋅35) 0⋅98 (0⋅16, 1⋅79)*

EQ-5D™ score 0⋅02 (0⋅01, 0⋅02) 0⋅02 ( 0⋅01, 0⋅03) 0⋅01 (0⋅01, 0⋅02)

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy; CIVIQ, Chronic Venous

Insufficiency quality-of-life Questionnaire; EQ-5D™, EuroQol – 5D. *P = 0⋅013 (EVLA versus UGFS, linear mixed-effect model). Regression

coefficients for the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) model are uninformative because a non-linear model was applied (regression coefficients of

natural spline function); Fig. S1 (supporting information) shows the relation between time after treatment and EQ VAS.

Table 3 Distribution of reflux in 193 legs of patients who attended the 5-year follow-up visit

Conventional surgery (n = 63) EVLA (n = 63) UGFS (n = 67) P*

GSV reflux

Above-knee 8 (13) 11 (17) 35 (52) <0⋅001†

Below-knee 17 (27) 17 (27) 15 (22) 0⋅412

Missing 9 (14) 14 (22) 19 (28)

AASV reflux 3 (5) 8 (13) 8 (12) 0⋅133

Missing 10 (16) 17 (27) 17 (25)

SFJ reflux 8 (13) 14 (22) 21 (31) 0⋅003‡

Missing 0 (0) 6 (10) 1 (1)

Neovascularization

Grade I 17 (27) 2 (3) 3 (4) <0⋅001‡

Grade II 11 (17) 8 (13) 3 (4) 0⋅009§

Refluxing tributaries

Above-knee 16 (25) 22 (35) 20 (30) 0⋅426

Below-knee 18 (29) 15 (24) 21 (31) 0⋅106

Values in parentheses are percentages. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy; GSV, great saphenous vein;

AASV, anterior accessory saphenous vein, SFJ, saphenofemoral junction. *χ2 test. †P < 0⋅050, conventional surgery and EVLA versus UGFS; ‡P < 0⋅050,

EVLA and UGFS versus conventional surgery; §P < 0⋅050, conventional surgery versus UGFS (all χ2 test).

Secondary outcomes EQ-5D™ or EQ VAS scores, no major changes between

or within the groups were found when compared with the

Absence of above-knee GSV reflux (categories 3 and 4)

univariable analysis (data not shown).

At 5 years in the conventional surgery and EVLA groups,

the estimated cumulative proportion of legs without Clinical class

above-knee GSV reflux was 85 (95 per cent c.i. 73 to 92)

In the linear mixed-effect model, there was no difference

and 82 (72 to 90) per cent respectively (Fig. 3), compared

in the distribution of class C between legs treated by

with 41 (30 to 53) per cent in the UGFS group. Patients

conventional surgery (odds ratio (OR) 1⋅4, 95 per cent c.i.

treated with conventional surgery or EVLA were three

1⋅2 to 1⋅6), EVLA (OR 1⋅3, 1⋅1 to 1⋅5) or UGFS (OR 1⋅3,

times more likely to have absence of above-knee GSV

1⋅1 to 1⋅5) over time.

reflux than patients in the UGFS group after 5 years of

follow-up (UGFS/EVLA RMST ratio: 0⋅7, 95 per cent c.i. Saphenofemoral junction reflux

0⋅6 to 0⋅8; UGFS/CS RMST ratio: 0⋅7, 0⋅6 to 0⋅8).

More legs in the UGFS and EVLA groups had persisting or

recurrent reflux at the SFJ than limbs in the conventional

Health-related quality-of-life scores surgery group at 5 years of follow-up (P < 0⋅001) (Table 3).

Over time, CIVIQ scores were significantly lower (indi- No significant differences were observed between EVLA

cating better disease-specific quality of life) in the EVLA and UGFS (P = 0⋅237).

than in the UGFS group in the linear mixed-effect model

(Fig. 4). There were no significant differences between Neovascularization

EVLA and conventional surgery groups. At 5 years, 44 (95 per cent c.i. 33 to 58) per cent of legs in

EQ-5D™ scores improved slightly in all three groups the conventional surgery group, 11 (5 to 20) per cent in the

over time (Table 2). EQ VAS scores deteriorated in all three EVLA group and 3 (1 to 9) per cent in the UGFS group had

groups over time (Fig. S1, supporting information). When developed some degree of neovascularization. Legs treated

age was included in multivariable analyses of CIVIQ, by conventional surgery were more likely to develop

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1190 S. K. van der Velden, A. A. M. Biemans, M. G. R. De Maeseneer, M. A. Kockaert, P. W. Cuypers, L. M. Hollestein et al.

1·0 1·0

Probability of not undergoing additional treatment

Probability of not undergoing reintervention

0·8 0·8

0·6 0·6

0·4 0·4

CS CS

EVLA EVLA

UGFS UGFS

0·2 0·2

0 1 2 3 4 5 0 1 2 3 4 5

Time after treatment (years) Time after treatment (years)

No. at risk No. at risk

CS 69 67 64 59 57 25 CS 69 62 58 53 48 22

EVLA 78 71 68 62 57 34 EVLA 78 65 58 47 42 18

UGFS 77 66 58 54 47 26 UGFS 77 70 65 54 46 22

Fig. 5 Freedom from reinterventions of above-knee great Fig. 6Freedom from additional treatments after conventional

saphenous vein after conventional surgery (CS), endovenous surgery (CS), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and

laser ablation (EVLA) and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) for great

(UGFS) for great saphenous varicose veins. P < 0⋅001 (log rank saphenous varicose veins. Additional treatments included

test) treatments of the anterior accessory saphenous vein, great

saphenous vein below knee level, and tributaries above and below

neovascularization grade I than those treated by EVLA knee level. P = 0⋅546 (log rank test)

(OR 12⋅9, 95 per cent c.i. 2⋅8 to 59⋅2) or UGFS (OR 1⋅5,

1⋅2 to 1⋅8) at 5 years. However, the proportion of patients

with grade II neovascularization was similar following respectively versus 0 per cent in the UGFS group) (Table S1,

conventional surgery and EVLA (P = 0⋅606) (Table 3). supporting information).

Progression of disease Discussion

Progression of disease did not differ between conventional

surgery (OR 4⋅2, 3⋅2 to 5⋅5), EVLA (OR 4⋅4, 3⋅3 to 5⋅9) This study demonstrated that total obliteration or absence

and UGFS (OR 4⋅1, 3⋅1 to 5⋅4) groups over time. of the GSV was more frequent in legs of patients

treated with conventional surgery or EVLA than in

Reinterventions and additional treatments those treated with UGFS after 5 years of follow-up.

During the 5-year follow-up, 32 per cent of legs treated Above-knee GSV reflux was more frequently present

initially with UGFS required one or more reinterventions after UGFS. Disease-specific HRQoL outcomes were

of the GSV above the knee (Fig. 5). Conversely, only 10 better in patients treated with EVLA than in those treated

per cent of limbs in the conventional surgery and EVLA with UGFS.

groups had one or more reinterventions over time. In Two RCTs7,8 have compared the results of conventional

the UGFS group, GSVs above knee level were more surgery and EVLA at 5 years’ follow-up, showing absence

often retreated with UGFS than those in the conventional or obliteration of the treated GSV in 90–100 per cent

surgery or EVLA group (P < 0⋅001) (Table S1, supporting following conventional surgery and 82–93 per cent after

information). EVLA. In the present study, the proportion of patients

The number and types of additional treatments were with absence of the GSV after conventional surgery (85

similar among the three groups (Fig. 6), except for UGFS per cent) was lower than that reported in other studies with

of the GSV below knee level which was performed only in 5 years of follow-up4,7,8,17 . There are several possible expla-

conventional surgery and EVLA groups (5 and 11 per cent nations for this discrepancy, such as violation of protocol

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Treatment of great saphenous varicose veins 1191

and randomization, ‘blind’ stripping and definition of out- hence induces prompt recanalization of an initially formed

come. Four patients with anatomical failure did not receive thrombus in the GSV. Indeed, as albumin neutralizes

the allocated conventional surgery, but only high ligation the sclerosant drug, this neutralizing effect will be more

or UGFS. However, owing to the intention-to-treat design pronounced where the blood volume is larger, which may

of the initial RCT, these patients were analysed in the result in less efficacious damage of endothelial cells at

conventional surgery group. Stripping was not guided by the site of inflow from a tributary25 . Reflux at the SFJ

ultrasound imaging, and ‘blind’ stripping of the above-knee was not treated, as is conventional for EVTA or UGFS

GSV may have been incomplete. In a prospective study18 treatment. In a small RCT6 , however, additional high

looking at completeness of stripping related to quality of ligation at the SFJ in UGFS-treated patients resulted

life, a segment of GSV could be found at duplex ultra- in obliteration rates of 58 per cent, compared with 54

sonography after 2 years in more than half of patients. per cent in the conventional surgery group at 5 years’

The present authors’ definition of treatment success was follow-up. Adding high ligation in the UGFS group may

very strict: if the GSV was present segmentally above knee have influenced the final results in this particular study6 ,

level, this was considered an anatomical failure (this was but more studies are needed to confirm these findings. It

the case in 4 limbs). In the present study, after treatment should be acknowledged that, if UGFS is combined with

with EVLA, the anatomical success rate (77 per cent) was high ligation, it can no longer be considered a non-invasive

comparable to the findings of several long-term prospec- treatment.

tive studies5,19,20 that reported GSV obliteration rates of Several studies have found that UGFS is less effective

between 75 and 90 per cent, but slightly lower than in in large than in smaller saphenous veins20,26 . The mean

previously published RCTs7,8 with comparable length of GSV diameter was greater than 6 mm, and this might

follow-up. This difference may again be explained by the have resulted in a higher recanalization rate. Neverthe-

difference in definition of treatment success7,8 . Interest- less, UGFS can be a valuable alternative in older patients,

ingly, the proportion of patients with GSV reflux during when there are contraindications to conventional surgery

follow-up was similar to that of other RCTs7,8 . Other pos- or EVTA, and in patients with small-diameter saphenous

sible explanations are the difference in study design (ran- veins20 . UGFS may also be an excellent choice for the

domized versus prospective) and selection bias, because the treatment of patients with symptomatic recurrent varicose

proportion of patients lost to follow-up in the present veins, and can easily be used in combination with other

study was far lower than in other studies (13⋅8 per cent techniques27,28 . Therefore, UGFS should still be consid-

(31 of 224) versus 21⋅3 per cent5 , 36⋅7 per cent7 and ered a valuable treatment option in selected patients with

32⋅9 per cent8 ). varicose veins.

The obliteration rate after UGFS was 20–50 per cent In the UGFS group disease-specific HRQoL scores dete-

lower than in previous mid- and long-term reports of riorated, whereas the HRQoL in the conventional surgery

RCTs and prospective cohort studies6,21,22 . This difference and EVLA groups remained stable over time. This dete-

in UGFS efficacy between studies might be due to factors rioration is probably related to the presence of persisting

such as treatment protocol of UGFS, combination therapy above-knee GSV reflux despite retreatment of the GSV.

(adding phlebectomies or high ligation) and inclusion of These limbs were mostly retreated with UGFS, which

large-diameter GSVs. The GSV was punctured at the was a less effective technique than conventional surgery or

level of the knee and a single direct injection was usually EVLA. One long-term prospective study29 reported a sig-

performed, possibly decreasing the efficacy of the injected nificant improvement of patients’ symptoms, lifestyle and

foam at the proximal thigh23 . Only one retreatment Aberdeen Varicose Vein Symptom Severity scores follow-

of the GSV was allowed during the first year, whereas ing UGFS in 285 patients. Retreatment was required in

other studies allowed more retreatments22 . In addition, only 15 per cent of limbs during 5-year follow-up, com-

mean volumes of injected foam in the first session were pared with 32 per cent of legs in the present study. How-

lower than in other studies6,20,21,24 . However, if UGFS is ever, there might have been some bias in their results, as it

repeated over time and larger volumes of foam are used, was a non-randomized study.

it can be a very effective treatment20 . In the present study, The difference in HRQoL and VAS scores between

concomitant phlebectomies of refluxing tributaries were groups could have been influenced by age, as patients

not performed systematically at the time of UGFS of the undergoing EVLA were younger than those having

GSV, in contrast with the previously published four-arm UGFS or conventional surgery. However, adjustment

RCT21 . It can be hypothesized that persisting inflow from for age in the HRQoL analysis gave results similar to

tributaries locally reduces the effect of sclerotherapy and those of the univariable analysis. SFJ reflux was present

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1192 S. K. van der Velden, A. A. M. Biemans, M. G. R. De Maeseneer, M. A. Kockaert, P. W. Cuypers, L. M. Hollestein et al.

more frequently following UGFS and EVLA than after unilateral inclusion. Fourth, 13⋅8 per cent of patients (31

conventional surgery. In another study30 , comparing limbs) were lost to follow-up at 5 years because the patient

EVLA versus conventional surgery performed with local had discontinued, died or moved. However, this value is

tumescent anaesthesia, duplex-detected saphenofemoral lower than that reported in similar studies7,8 .

reflux was also significantly more frequent 2 years after This study suggests that conventional surgery and

EVLA than after conventional surgery (18 versus 1 per cent EVLA are more effective than UGFS in the treatment

respectively). Apart from the use of a special technique of GSV reflux. EVLA provides better disease-specific

invaginating the GSV stump after high ligation, the fact patient-reported outcomes than UGFS after 5 years of

that these operations were performed using local tumescent follow-up. Thus, conventional surgery and EVLA can

anaesthesia may also have reduced operative trauma, and both be considered efficient treatments with long-term

hence minimized the risk of developing neovascularization. beneficial effects in patients with GSV reflux.

Interestingly, although duplex ultrasonography-detected

grade I neovascularization was observed more frequently

Acknowledgements

in the conventional surgery group than in the other two

groups, the proportion of limbs with clinically relevant The authors thank J. Giang for her contribution to the data

neovascularization grade II was similar between the con- collection; E. Andrinopoulou for help with the analysis; M.

ventional surgery and EVLA groups (17 versus 13 per Senders for secretarial support; J. van der Velden, E. Bever-

cent respectively). In addition, progression of disease was dam and A. Goedkoop for their help with the follow-up of

similar in the three groups. These observations suggest trial participants; and the vascular technologists at Catha-

that the extent of disease progression is independent of rina Hospital, Eindhoven.

venous treatment5,14,20 . Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The comparable clinical evolution and progression

of disease in the three treatment groups is consistent References

with previous findings7,8,31 . Rasmussen and colleagues21

reported the 3-year follow-up of a RCT comparing four 1 Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, Eklof BG,

Gillespie DL, Gloviczki ML et al. The care of patients with

different GSV treatments (conventional surgery with

varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases:

local tumescent anaesthesia, EVLA, radiofrequency abla-

clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular

tion and UGFS, all with concomitant phlebectomies) and Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011;

observed no differences between the four groups in Venous 53(Suppl): 2S–48S.

Clinical Severity Score and quality of life; nor was there 2 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

a difference in the incidence and anatomical location of Varicose Veins in the Legs: the Diagnosis and Management of

recurrent tributaries. Recently, a RCT31 comparing con- Varicose Veins; 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/

ventional surgery, EVLA with high ligation, and EVLA CG168/chapter/introduction [accessed 5 September 2014].

without high ligation confirmed that clinical recurrence 3 Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower

did not differ between the three treatment groups up to limbs – guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int

Angiol 2014; 33: 87–208.

6 years after treatment. It is clear that, irrespective of the

4 Blomgren L, Johansson G, Dahlberg-AKerman A, Norén A,

technique employed to treat varicose veins, progression

Brundin C, Nordström E et al. Recurrent varicose veins:

of disease cannot be stopped in the long term. Genetic incidence, risk factors and groin anatomy. Eur J Vasc

predisposition and other patient-related factors (such as Endovasc Surg 2004; 27: 269–274.

body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above, pregnancy after the 5 Proebstle TM, Alm BJ, Göckeritz O, Wenzel C, Noppeney

intervention) certainly play a role32,33 . After several years, T, Lebard C et al. Five-year results from the prospective

tortuous neovascular veins or (newly) refluxing veins at the European multicentre cohort study on radiofrequency

SFJ may connect with the AASV or superficial refluxing segmental thermal ablation for incompetent great saphenous

tributaries of the thigh or leg, resulting in clinically obvious veins. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 212–218.

recurrent varicose veins34 . 6 Kalodiki E, Lattimer CR, Azzam M, Shawish E,

Bountouroglou D, Geroukalos G. Long-term results of a

This study has several limitations. First, blinding of

randomized controlled trial on ultrasound-guided foam

physicians, patients and outcome assessors was not possible sclerotherapy combined with saphenofemoral ligation vs

owing to the nature of the interventions. Second, patients standard surgery for varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55:

in the EVLA group were significantly younger than those 451–457.

in the other two groups, although probably due to chance. 7 Disselhoff BC, der Kinderen DJ, Kelder JC, Moll FL.

Third, HRQoL analysis was possible only in patients with Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Treatment of great saphenous varicose veins 1193

endovenous laser ablation with cryostripping for great 21 Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Serup J, Bjoern L, Vennits B,

saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1107–1111. Blemings A et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing

8 Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Blemings A, Eklof B. endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam

Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser sclerotherapy, and surgical stripping for great saphenous

ablation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with varicose veins with 3-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg 2013; 1:

clinical and duplex outcome after 5 years. J Vasc Surg 2013; 349–356.

58: 421–426. 22 Chapman-Smith P, Browne A. Prospective five-year study

9 Biemans AA, Kockaert M, Akkersdijk GP, van den Bos RR, of ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy in the treatment

de Maeseneer MG, Cuypers P et al. Comparing endovenous of great saphenous vein reflux. Phlebology 2009; 24:

laser ablation, foam sclerotherapy, and conventional surgery 183–188.

for great saphenous varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 23 Rabe E, Pannier F; for the Guideline Group. Indications,

727–734. contraindications and performance: European Guidelines

10 Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, Carpentier PH, for Sclerotherapy in Chronic Venous Disorders. Phlebology

Gloviczki P, Kistner RL et al. Revision of the CEAP 2014; 29(Suppl): 26–33.

classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus 24 Shadid N, Ceulen R, Nelemans P, Dirksen C, Veraart J,

statement. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40: 1248–1252. Schurink WG et al. Randomized clinical trial of

11 Tessari L, Cavezzi A, Frullini A. Preliminary experience with ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery for the

a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins. incompetent great saphenous vein. Br J Surg 2012; 99:

Dermatol Surg 2001; 27: 58–60. 1062–1070.

12 De Maeseneer M, Pichot O, Cavezzi A, Earnshaw J, van Rij 25 Parsi K, Exner T, Connor DE, Herbert A, Ma DD, Joseph

A, Lurie F et al. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins JE. The lytic effects of detergent sclerosants on

of the lower limbs after treatment for varicose veins – UIP erythrocytes, platelets, endothelial cells and micro-

consensus document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011; 42: particles are attenuated by albumin and other plasma

89–102. components in vitro. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; 36:

13 Launois R, Reboul-Marty J, Henry B. Construction and 216–223.

validation of a quality of life questionnaire in chronic lower 26 Shadid N, Nelemans P, Lawson J, Sommer A. Predictors of

limb venous insufficiency (CIVIQ). Qual Life Res 1996; 5: recurrence of great saphenous vein reflux following

539–554. treatment with ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

14 EuroQol Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the Phlebology 2015; 30: 194–199.

measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 27 Darvall KA, Bate GR, Adam DJ, Silverman SH, Bradbury

1990; 16: 199–208. AW. Duplex ultrasound outcomes following

15 De Maeseneer MG, Vandenbroeck CP, Hendriks JM, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of symptomatic

Lauwers PR, Van Schil PE. Accuracy of duplex evaluation recurrent great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc

one year after varicose vein surgery to predict recurrence at Surg 2011; 42: 107–114.

the sapheno-femoral junction after five years. Eur J Vasc 28 De Maeseneer M. Surgery for recurrent varicose veins:

Endovasc Surg 2005; 29: 308–312. toward a less-invasive approach? Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc

16 Uno H, Claggett B, Tian L, Inoue E, Gallo P, Miyata T Ther 2011; 23: 244–249.

et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the 29 Darvall KA, Bate GR, Bradbury AW. Patient-reported

between-group difference in survival analysis. J Clin Oncol outcomes 5–8 years after ultrasound-guided foam

2014; 32: 2380–2385. sclerotherapy for varicose veins. Br J Surg 2014; 101:

17 Dwerryhouse S, Davies B, Harradine K, Earnshaw JJ. 1098–1104.

Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of 30 Rass K, Frings N, Glowacki P, Hamsch C, Gräber S, Vogt

reoperation for recurrent varicose veins: five-year results of a T et al. Comparable effectiveness of endovenous laser

randomized trial. J Vasc Surg 1999; 29: 589–592. ablation and high ligation with stripping of the great

18 MacKenzie RK, Paisley A, Allan PL, Lee AJ, Ruckley CV, saphenous vein: two-year results of a randomized

Bradbury AW. The effect of long saphenous vein stripping clinical trial (RELACS study). Arch Dermatol 2012; 148:

on quality of life. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 1197–1203. 49–58.

19 Ravi R, Trayler EA, Barrett DA, Diethrich EB. Endovenous 31 Flessenkämper I, Hartmann M, Hartmann K, Stenger D,

thermal ablation of superficial venous insufficiency of the Roll S. Endovenous laser ablation with and without high

lower extremity: single-center experience with 3000 limbs ligation compared to high ligation and stripping for

treated in a 7-year period. J Endovasc Ther 2009; 16: treatment of great saphenous varicose veins: results of a

500–505. multicentre randomized controlled trial with up to

20 Myers KA, Jolley D. Outcome of endovenous laser therapy 6 years follow-up. Phlebology 2014; [Epub ahead

for saphenous reflux and varicose veins: medium-term of print].

results assessed by ultrasound. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 32 Fischer R, Chandler JG, Stenger D, Puhan MA, De

2009; 37: 239–245. Maeseneer MG, Schimmelpfennig L. Patient characteristics

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1194 S. K. van der Velden, A. A. M. Biemans, M. G. R. De Maeseneer, M. A. Kockaert, P. W. Cuypers, L. M. Hollestein et al.

and physician-determined variables affecting in varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency. Phlebology

saphenofemoral reflux recurrence after ligation and 2012; 27: 329–335.

stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2006; 43: 34 De Maeseneer MGR, Biemans AA, Pichot O. New concepts

81–87. on recurrence of varicose veins according to the different

33 Krysa J, Jones GT, van Rij AM. Evidence for a genetic role treatment techniques. Phlébologie 2013; 66: 54–60.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Reinterventions and additional treatments (Word document)

Fig. S1 EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) scores in the 5 years after conventional surgery, endovenous laser

ablation and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for great saphenous varicose veins (all groups combined) (Word

document)

Snapshot quiz

Snapshot quiz 15/9

Answer: The picture shows an interstitial hernia, causing small bowel obstruction. A 76-year-old woman with a history

of previous total abdominal hysterectomy was admitted with symptoms and signs of small bowel obstruction. An

emergency laparotomy was carried out and a large left-sided interstitial hernia containing distal jejunum was found.

The small bowel was bruised but viable with an obvious transition point. A primary suture repair of the interstitial

hernia was performed with complete obliteration of the interstitial space.

An interstitial hernia is a rare type of hernia that passes between the layers of the abdominal wall. Classically, as shown

here, an interstitial hernia passes through a defect in the transversus abdominus and internal oblique muscles, but not

through the intact aponeurosis of the external oblique. These hernias may not present with an obvious lump and may

go unrecognized. There should be a high index of suspicion in a patient with previous abdominal surgery presenting

with symptoms and signs of small bowel obstruction. Meticulous closure of the abdominal wall at the time ofinitial

surgery remains the best way of avoiding interstitial hernia formation.

© 2015 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2015; 102: 1184–1194

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- High Yield Surgery Shelf Exam Review CompleteDocument11 pagesHigh Yield Surgery Shelf Exam Review Completeslmrebeiro92% (12)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CANNABISDocument5 pagesCANNABISGeorgina AttipoeNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Nursing ConceptDocument21 pagesPerioperative Nursing ConceptArgee Alonsabe100% (8)

- EtoposideDocument3 pagesEtoposideNoamiNo ratings yet

- National healthmission-NHMDocument52 pagesNational healthmission-NHMNancy Singh100% (2)

- IridologyDocument8 pagesIridologyNop Tan0% (1)

- Doctors and ProgrammeDocument28 pagesDoctors and ProgrammePabitra ThapaNo ratings yet

- NACODocument10 pagesNACOkammanaiduNo ratings yet

- DR Tahir Eye mcqs1Document10 pagesDR Tahir Eye mcqs1YUAN LINo ratings yet

- Abstract 22-A-212-AACR PDFDocument2 pagesAbstract 22-A-212-AACR PDFOscar Alonso LunaNo ratings yet

- Re-Brain Stimulation Conference 100223Document1 pageRe-Brain Stimulation Conference 100223Faisal Nouman BaigNo ratings yet

- Cerebellar AtaxiaDocument7 pagesCerebellar AtaxiaWasemBhatNo ratings yet

- Theresa Beauty 2020 Price List (JE:CL:TPY) - Compressed PDFDocument39 pagesTheresa Beauty 2020 Price List (JE:CL:TPY) - Compressed PDFSandra Koh100% (1)

- Kelompok 6 Sesi II KELAS ADocument6 pagesKelompok 6 Sesi II KELAS AlindaNo ratings yet

- Iridology BooksDocument150 pagesIridology Bookspapuagine77100% (1)

- GuideToClinicalEndodontics v6 2019updateDocument40 pagesGuideToClinicalEndodontics v6 2019updateLorena MarinNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Philippine Health StatisticsDocument223 pages2016 - Philippine Health StatisticsMara Benzon-BarrientosNo ratings yet

- Using The ABCDE Approach For All Critically Unwell PatientsDocument6 pagesUsing The ABCDE Approach For All Critically Unwell PatientsYustitiNo ratings yet

- Dispensing AnisometropiaDocument28 pagesDispensing Anisometropiahenok biruk100% (2)

- WHO - 2020 - VCAG 12th Meeting ReportDocument38 pagesWHO - 2020 - VCAG 12th Meeting ReportnomdeplumNo ratings yet

- Immunity by Design: An Artificial Immune System: Steven A. Hofmeyr and Stephanie ForrestDocument8 pagesImmunity by Design: An Artificial Immune System: Steven A. Hofmeyr and Stephanie ForrestdkasrvyNo ratings yet

- Temblor de HolmesDocument7 pagesTemblor de HolmesIan Luis Flores SaavedraNo ratings yet

- 206 Lab Ex - 6 - Bacterial CulturesDocument10 pages206 Lab Ex - 6 - Bacterial CulturesZiah TirolNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan (1) Day 1Document20 pagesNursing Care Plan (1) Day 1FATIMA PANDAOGNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Orchiectomy in Bilateral Cryptorchid DogsDocument8 pagesCase Report: Orchiectomy in Bilateral Cryptorchid Dogslastbeat productionNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Features SectionDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Features SectiongekdiahNo ratings yet

- The Advantages of External DR PDFDocument13 pagesThe Advantages of External DR PDFalitNo ratings yet

- Thermoregulation 2017Document29 pagesThermoregulation 2017janainaNo ratings yet

- Multimorbidity and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Adults in Northern Sudan: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesMultimorbidity and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Adults in Northern Sudan: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional StudyOwais SaeedNo ratings yet

- MDICU 5th Floor HandoverDocument5 pagesMDICU 5th Floor HandoverKailash KhatriNo ratings yet