Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Making of Fatehpur Sikri by Satish K Grover

The Making of Fatehpur Sikri by Satish K Grover

Uploaded by

Shivansh Kumar0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

161 views25 pagesFatehpur Sikri. was initially constructed by the last Sikriwal Rajput, Maharana Sangram Singh during the beginning of 16th century.

Original Title

The Making of Fatehpur Sikri by Satish k Grover

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFatehpur Sikri. was initially constructed by the last Sikriwal Rajput, Maharana Sangram Singh during the beginning of 16th century.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

161 views25 pagesThe Making of Fatehpur Sikri by Satish K Grover

The Making of Fatehpur Sikri by Satish K Grover

Uploaded by

Shivansh KumarFatehpur Sikri. was initially constructed by the last Sikriwal Rajput, Maharana Sangram Singh during the beginning of 16th century.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 25

THE MAKING OF

FATEHPUR SIKRI

The Sir George Birdwood Memorial Lecture by

Satish K. Davar, BA, BArch, MRP, AIA, AITP

delivered to the Commontealth Section of the Society

on Tuesday, 29th April, 1975, with Sir Fames Richards,

CBE, ARIBA, in the Chair

Tut CHAIRMAN: Our speaker this evening is

Mr. Satish K. Davar, who is going to talk about

the remarkable story of Fatehpur Sikri, which

was built by that great patron of the arts, the

Mughal Emperor Akbar, in the latter part of the

sixteenth century. It was only eccupied as the

administrative capital of Akbar's empire for

fifteen years, after w! ‘it was deserted; and it

has remained deserted ever since, that is for

nearly four centuries. The central parts of the

city, however, are still in a wonderful state of

preservation which has made Fatehpur Sikri one

of the most admired architectural monuments in

India, It is visited by thousands of people both

for its beauty and for its fascinating combination

‘of Mughal, Rajpit and Persian styles of architec

vure. I emphasize that it is the central parts of

the city that are so remarkably preserved. These

are what the visitors explore. But within the

enclosing walls there are acres more that are still

in tuins or of which traces only remain, and it

has been Mr. Satish Davar’s task during the past

Sik years of more to investigate and identify

these less known parts of the city. He is an

M a keen personal interest in Fatehpur

Siksi, for taking the chair to-day,

and then express my pleasure and gratitude

to the Royal Society of Arts for asking me

to present this Sir George Birdwood

Memorial Lecture. It was indeed an honour

The following lecture, which was

ay I first thank Sir James, who has.

architect, a planner and a historian, and when

the book he is preparing on the city is published

we shall know a great deal more about how the

city was designed and built. He is going to tell

us this evening about the progress of his re-

searches at Fatehpur Sikri and the conclusions

that he has drawn from them.

‘This series of annual lectures was founded as

fat back a8 1920 in memory of Sir George

Birdwood, who lived from 1830 to 1917. He was

a great authority on Indian art and design, was

2 voluminous writer, a scholar and an enthusi=

ast. He was also a Member of the Council of this,

Society for over twenty years and did much to

bring the arts of India within its purview. Past

Birdwood Lectures have dealt with a fascinating

range of Indian subjects. I have been told only

this evening, incidentally, that the Chairman at

the first Birdwood Lecrure was none other than

Lord Curzon, which makes me very proud to be

sitting in the same place! I am sure Mr. Satish

Davar will give a lecture that Birdwood himself

would have velued.

illustrated, tas then delivered.

the scattered ruins of Fatehpur Sikri with

groups of student architects from Delhi

School was a stimulating experience which

eventually led me to undertake fairly exten-

sive site surveys over five winters in order to

reconstruct (on paper) this vast area which

was meelected and unrecorded so far. The

FiGure 1.

marble Chishti tomb in the Jami Masjid courtyard

View through Buland Darwazé leading to the white

experience, interpret and analyse Fatehpur

Sikri as a living city of Mughal India. These

site explorations, besides providing a work-

ing base, reveal the enormous development

potential of this area for educational,

archaeological and tourism purposes. At the

same time they make me acutely aware of

the rapid deterioration of these monuments

and the surrounding ruins, taking place

constantly, at all levels, due to official and

public indifference. I am extremely con-

cerned about this thoughtless unmaking of

Fatehpur Sikri, which unfortunately seems

like an irreversible process.

It was a little over 400 years ago, when

Michelangelo was busy working on his plans

for St. Peter’s in Rome, that the third

Mughal Emperor Akbar—a contemporary

of Queen Elizabeth I of England—decided

to build a new city for his court and residence

near Agri in India. Its splendid palaces with

their sunken gardens, multi-storied pleasure

pavilions, and various courts for public

appearance and state work are known for

ghaie evant

= alaeanee amd an intenealey

country, with its lofty southern gate and a

gem-like miniature marble tomb for the

Chishti saint, is a fascinating complex; and

most of the visitors end their visit to the

monuments here.

To comprehend Fatehpur Sikri as a city

we should look beyond this tourist’s com-

plex, even beyond the Sikri of the Archae-

ological Survey, and look at Akbar’s city in

its entirety in a conceptual way to ascertain

if any ground rules, traditional practices,

topographical considerations or special cir-

cumstances, are manifest in this sixteenth-

century town layout. Architecture and town

layouts are closely related arts and it is per-

haps a fair assumption that one cannot have

beautiful building complexes in’ a badly

considered town layout. No work of art that

has stood the test of time is a product of

chance or accident, much less a designed

city, which is a synthesis of many skills,

enormous teamwork, indigenous influences,

and, it is to be hoped, an overriding inspira-

tion. A city is the largest visual manifestation

Sa E

es

were concentrated the arts of India in a

cosmopolitan setting under one of the great-

est and most humane brains in Indian

history. A palace citadel was built and a

metropolitan city planned in less than a

decade. The speed of construction, men-

tioned in several contemporary accounts,

meant numerous groups of builders and

artisans working on separate projects rising

at the same time.” The situation can be quite

chaotic without an overall concept and

specific guidelines for the entire area. What

were those guidelines ? What was the con-

cept or the art process ? Here, we venture to

participate in that art process, which by

revealing itself would perhaps augment the

art product. This is an inquiry into the

mental anticipation of a combination of |

means to achieve this end product.

Fatehpur Sikri was a vigorous city, a

product of exceptional circumstances. De- |

signed from scratch and speedily built,

utilizing all available talent and unlimited

| anxious Akbar visited several shrines and

holy men where he offered prayers and

sought blessings for the birth of an heir and

successor to the throne. Amongst the Muslim

divines of that time was Salim Chishti,? who

had recently returned to his unassuming

hermitage on the Sikri hill after a consider-

able absence. He was a well-travelled man,

and had made more than twenty pilgrimages

to Mecca, most of them on foot. His spread-

ing fame brought Akbar barefooted to his

door. It was the spell of the octagenarian

saint’s personality, or his prophecy that

Akbar would have three sons, that comforted

Akbar’s troubled mind, The impact was

immediate. A few royal palaces were

hurriedly constructed adjoining the Shaikh’s

house as Akbar decided to reside on Sikri

hill. The decision to build an entire city on

the spot and to move the court there per-

manently, followed a year later.

Akbar’s passion for building was insati-

able. Despite the fact that he had already

greatest of all his architectural projects. And

yet in less than fifteen years, when Akbar

moved his court to Lahore, the city was to

be totally abandoned, to the point that

travellers would find itunsafe to go through it.

Several factors make Sikri unique. First,

its spiritual origin is the most significant.

The humble cave of Salim Chishti became

a key point in the town concept. Secondly,

the enormous speed of its construction

helped to maintain the mood. Thirdly, the

‘comparatively open plan of the city because

of Chishti’s influence on the king. Fourthly,

the complex and extraordinary personality

‘of young Akbar. Finally, its short lite-span,

which was responsible for the preservation

of its theme and character,

Few cities in the world have been built

with such impulse and rapidity. The whole

fabric of the city was woven around the

physical and spiritual presence of the saint

Salim Chishti. Many important roads and |

streets of Sikri radiating from the centre set

the town pattern (Figure 27). Since the

Chishti presence drew a large number of

pilgrims from distant parts of the country

to the little cave, the footpaths which thus

developed eventually became the major

roadways for the royal passage.

‘Most cities are works of many generations,

each adding its own themes and new areas,

frequently replacing the old. Many styles can.

be seen side by side in most cities, depicting,

the different stages of their growth. But

Sikri is the work of one man, in a single

phase of his life. It was built with great

energy while the mood lasted and completely

abandoned soon after. It is a frozen moment

in history. Its modest chambers, activated

corridors and open terraces reflect that mood.

What comes through with startling clarity

is the active and keen mind of Akbar, his

immense ambitions, intellectual subtlety,

exquisite taste, and the sense, the drama, of

royalty. Each building reveals his imaginative

and inventive genius. The growth of the

town reflects the growth of Akbar’s mind,

whose horizons were widening even faster

than the boundaries of his expanding empire.

Akbar was discovering himself. He was

discovering the people and the country

around him, and was interested in distant

Cane Erg ca Sate aca Cia

cations were dispensed with, a new civic

relationship developed between the town

and the hill-top palaces. The influence of

fine buildings was skilfully radiated out-

wards, thereby articulating the whole fabric

of the city.

Among other things, architecture is

defined as a ‘place prepared in time and.

space for human activity’. This definition

can be stretched to town design as well and

no doubt time and space are its two essential

aspects besides the various human episodes

and historical events that it gradually assi-

milajes. In this context it would be appro-

priate at this stage to consider the ‘moment’

and ‘site’ as the two coordinates of the

situation: the moment being its dynamic

aspect, its symbolical projection in time. The

site is static, a fundamental geopolitical

proposition. The ‘site’ at Sikri was a barren

Tocky escarpment about 100 to 150 feet

above ground level, forming part of the

upper Vindhyan range that extends in a

south-westerly direction for about two miles.

To the north-west of this ridge lies the wide

and shallow valley of the Khari river,

‘bounded on the other side by the low ranges

of the Bandrauli hills. On this ridge, a little

over a mile from Akbar’s town, stood an old

Rajpit citadel held by the Sikarwar Rajpits

for several centuries. It was the Sikarwars

who gave the place its name Sikri. One can

still see the last remains of their palaces on

the hill! Their town spread towards the

north and north-east of the ridge in the

direction of the present Bharatpur Road.

From the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries,

Sikri was somewhat of a frontier station,

feeling the pressure exerted by the Turks and

Pathdns from the north and that of the

Rajptits from the neighbouring states in the

south. The lurking tension in the area made

it strategically important and gave it a cer-

tain political significance. Even after Agra

became a Ladi Capital in the beginning of

the sixteenth century, Sikri maintained its

significance as a military gathering point.

‘A quarter of a century later, Babur,

the first Mughal—Akbar’s grandfather—

defeated the last Lodi king near Delhi,

pushed on to Agra and later encamped at

Sikri to meet the united Rajpat forces under

| ok seed dekla lncdeechin Af Dank Ganck at

FIGURE 3.

open revolt. Babur himself has recorded®

that the heat was unusually oppressive. His

soldiers longed for the cool air of Kabul.

Even his best generals were eager to return

home. Babur spent three or four weeks at |

Sikri arranging his army and artillery for the

decisive battle, waiting for reinforcements to

arrive from neighbouring Bayana. The mood

at the camp was grim and gloomy. In a

determined speech to his dispirited officers,

Babur made his memorable renunciation of

wine, smashed all his cherished gold and

silver drinking-cups, poured wine stocks on |

to the ground and pledged that he would

henceforth lead a life of austerity. His actions

galvanized the troops. Each man seized the

Koran and took an oath. Then they advanced

on the opponent Rajpit formations. The

two armies clashed about ten miles west of

Sikri. Spirits were high and the charges

desperate. Babur carried the day. His most

critical moment was overcome. With two

smashing victories in less than a year Mughal

supremacy in northern India was established

beyond doubt. Overwhelmed, Babur called

the place ‘Shukri’—the Arabic term for

gratitude.

Sikri had still more to offer (Figure 3). Its

idge was also known for its quarries, and

chisti cave

sik

citadel

“of sikarwer rajputs

Khari river

to

500

baburs army

from agra

cee

camp site

‘Site characteristics

at Agra. Abundance of good red sandstone,

ranging from rose pink to deep purple, so

near the site must have been a boon. Stone-

cutting was perhaps the oldest and largest

trade in this region. As a gesture to Salim

Chishti, the saintly man meditating in the

midst of wild animals, the stone-cutters of

the area who came to Sikri for their stone,

built a small mosque for his use (Figure 4).

So this little mosque around his cave was

completed some thirty years before Akl

Saigtrashai (Stone-cutters’ Mosque). Thus

the main characteristics of the site were an

old Rajpat citadel in the east that gave the

place its name; quarries in the west that

provided abundant building material; a river

in the north that was regulated to form a

lake; an army campsite and a battlefield

in the vicinity that had established the

Mughals; and the hill-top abode of Salim

Chishti, whose fame had caused Akbar’s

visit and subsequent determination to build

a dream city around this red rocky ridge.

‘Akbar was only thirteen years old when he

was hurriedly crowned in a garden on his

way to Delhi. He was quickly coming to his

own. Aided by his great physical strength

and personal courage everything seemed to

FIGURE 4.

Sketch of conjecturally restored Masjid-i-Sargtrdshan (Stone-

cutters’ Mosque), built thirty years before the founding of Fatehpur

his muslim chiefs, whose support was

essential for his stability. This enormous

courage and conviction places him without

doubt far ahead of his time.

The Rajpit threat was met in Akbar’s

characteristic style. The nearest state of

Jaipur was first won over, by a marriage to

a Jaipur princess. By a series of other con-

trivances, high offices and imperial honours,

Mughal-Rajpit cooperation spread from

administration and army to the realm of art

and culture. When he went to Sikri most of

Rajputana except Udaipur and Mewar had

accepted the Mughal supremacy and Sikri

was in a way the ‘Gateway to Rajputana’,

and through Rajputana to fertile Gujrat,

whose ports traded freely with Arabia.

Abul Fazl observes that from a feeling of

thankfulness for his constant success on the

Seensheiiette AD tthenaceutd al

philosophy and law. Akbar was twenty-eight

when he built his city. By then he had ruled

for fifteen years and his influence, wealth

and territories had multiplied. He was

already involved with deeper philosophical

ideas. His city reflects these attitudes. This

was the moment in time, impregnate with

enormous energy, social zeal and intellectual

vigour in every walk of life, a time fitted to

afford the freest play to his eminent qualities.

Near the fifty-year-old clock towet in the

main bazaar of present-day Fatehpur, next

to the newly constructed police station, lies

a tiny, elementary mosque that demands

further historical research and closer archae-

ological scrutiny. The location and layout

of the town suggest that his mosque was

important to the Mughals, and it seems to

have played a significant rdle in the design

Pl le

It is a quiet building of a domestic scale

and its super-structure seems to have been

rebuilt on an older plinth. Constructed

essentially with the local greyish blue

quartzite, its corners, mihrab and door-

frame have been emphasized by the use of

red sandstone. The mosque itself comprises

‘a covered area eleven feet by twenty-three

feet opening on to a court-yard twenty-four

feet by twenty-nine feet, enclosed by seven-

foot-high screen walls on the three sides

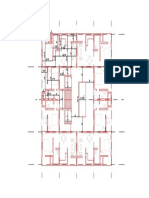

(Figures 5, 6 and 7). On account of the

increase in the number of visitors, perhaps,

another court-yard was added later to

accommodate larger assemblies. The outer

door altered the direction of the main

entrance, which is now from the west wall.

The open area towards the west between the

mosque and the main bazaar is still known

as Hat Pardo—it means ‘Market for the

Camp’, even though no market is held there

now. The word ‘Pardo’ brings to mind those

momentous three weeks in 1527 when

Babur’s soldiers camped in the area. Could

it then be the mosque or the spot where

Babur made a moving appeal to his officers

and stirred them to determined action lead-

ing to glorious success ?

This mosque, we find, is the focal point

of the town (Figure 8) as its walls went up

speedily on Royal orders. The town was

named Fatehabad (founded for victory),

though it eventually became known as

Fatehpur (victory town). For convenience

this mosque will be referred to as ‘Centric

Mosque’ in this paper.

The Masjid-i-Sangirdshan on the ridge,as

we know, was the other important landmark

that existed prior to the founding of the city.

‘This was perhaps a better-known mosque,

actively used by the Chishti family, the local

populace, and visitors from outside. Akbar’s

pilgrimage to this mosque, which was loaded

with personal associations and was the

raison d’étre for the new city, must have

added a great deal to its popularity. For easy

reference we call it ‘Chishti mosque’ in the

rest of this paper.

It was quite natural for the designers of

Fatehpur to utilize these two landmarks in

some manner to evolve the town plan around

them. As a first step in this direction they

ingenuity and imagination. Taking an axis

from the centric mosque parallel to the axis

of the ridge, and one from the Chishti

mosque at right angles to it, determined the

placement of a most unusual building—a

cross-shaped cdrdvansarai. Most cdrdvan-

sarais in India or elsewhere are rows of

rooms and open verandahs placed around a

square or rectangular courtyard. Sometimes

they can be polygonal, adjusted to fit an

Ficures 5, 6 and 7.

Ficure 8.

Centric mosque—its focal position in the town-layout suggests

that it woas important to the Mughals

irregular site. The idea of a cross-shaped

sarai (inn) for visitors to the two mosques at

the crossing of the axes through them was a

novel, logical and admirable decision arrived

at with keen intellectual clarity (Figure 9).

‘This was their most creative moment. This

not only helped to bind the two mosques and

the subserviant sardi together; it generated

a comprehensible relationship between the

group and the ridge, preparing a coherent

basis for further design decisions. The

Pukhté Sardi, as this building is called, can

be translated as an inn solidly built of

permanent materials (as opposed to mud

structures). The name only suggests that it

was among the first few public buildings

built for common use on royal orders. (The

endowment of public sardis and wells was a

common royal pictism; the numerous

examples on his Grand Trunk Road evince

Akbar’s concern in this respect.)

The Pukhtd Sardi had about 100 rooms

with attached verandahs opening on to a

thirty-foot-wide street. After the narrow

crooked lanes of present-day Fatehpur it is

a refreshing experience to find a straight,

wide street over a hundred yards long

(Figure 10). Unfortunately, the Pukhtd Sardi

lies in the populated part of the present town

and is not a protected monument. Its

individual occupants make additions and

alterations to suit their needs. Old structures

gnileses var anc then end new anile anmear.

FIGURE 10.

recognition, and lost for ever. Its three gates

have already disappeared during the last

decade and the main gate opening on to the

bazar (shopping street) stands sadly dis-

figured.§ Nevertheless, the relation of this

building with the two mosques and the

Jami Masjid that was built a little later can

be clearly seen in the aerial photograph

(Figure 11). The NE-SW wind of the sardi

had to be slightly adjusted in length to relate

it with the existing royal palaces, which were

temporarily built parallel to the Chishti

house and the contours of the ridge, prior to

the laying of the city.

The distance between the centre point of

the sardi and the centric mosque, measured

in units of Akbar’s time, is 300 Ilahi Gaz®

(lah Gaz cquals 30} in.). This distance

was then used as a module to fix the position

of other major town elements and important

structures (Figure 12). The grid, based on

eight super-squares each comprising nine

modular squares, determined the location of

the major city gates. The Agra gate, how-

ever, was placed on the axis of the existing

approach road from Agra, because of the

special significance of his first visit, when

Akbar used that road. Further up, the inter-

section of this road with the next super-grid

determined the placement of the Naubat

Khand Chowk, which was an open square

with gates in four directions and marked the

The surviving north-east wing of Pukhtd Sardi

city gates in the north of the ridge depended

on the already existing street pattern of the

earlier Sikarwar town.

It is interesting to note that the usage of

nine squares in architectural plans and

garden layouts has been an old tradition in

India with its ultimate source in ancient

mythology. Arabian mathematicians inte-

grated this Indian system into their own

synthesis of ancient systems.’® They utilized

squares based on the use of numerals 1 to 9,

in which numerical relationships reveal

characteristic visual patterns (Figures 13 and

14). Throughout the history of ideas we find

constant reference to mathematics as an

aesthetic; to the recognition of fundamental

orders, sequences and patterns. The square

formed on a nine-by-nine grid numbered

1 to g horizontally and vertically as illus-

trated, was the basis of a whole mathematical

system, which contained a numerical model

of the universe. Architecturally, the sub-

division of a square space into nine equal

squares offers the privileged use of the

central space, maintaining an implicit visual

relationship with its surround.

One of the most outstanding, and perhaps

the first, buildings in Akbar’s time is the

Garden Tomb built for his father—

Humayus, supervised by Akbar’s mother—

Hameeda Begum; this is to-day an imposing

etracmnre on the river hank in nresent New

Ficure 10.

recognition, and lost for ever. Its three gates

have already disappeared during the last

decade and the main gate opening on to the

bazar (shopping street) stands sadly dis-

figured.® Nevertheless, the relation of this

building with the two mosques and the

Jami Masjid that was built a little Jater can

be clearly seen in the aerial photograph

(Figure 11). The NE-SW wind of the sardi

had to be slightly adjusted in length to relate

it with the existing royal palaces, which were

temporarily built parallel to the Chishti

house and the contours of the ridge, prior to

the laying of the city.

The distance between the centre point of

the sardi and the centric mosque, measured

in units of Akbar’s time, is 300 Ilahi Gaz®

(Waki Gaz cquals 30} in.). This distance

was then used as a module to fix the position

of other major town elements and important

structures (Figure 12). The grid, based on

eight super-squares each comprising nine

modular squares, determined the location of

the major city gates. The Agri gate, how-

ever, was placed on the axis of the existing

approach road from Agri, because of the

special significance of his first visit, when

Akbar used that road. Further up, the inter-

section of this road with the next super-grid

determined the placement of the Naubat

Khand Chowk, which was an open square

with earec in four directinne and marked the

The surviving north-east wing of Pukhtd Sardi

city gates in the north of the ridge depended

on the already existing street pattern of the

Coe Sikarwar town.

interesting to note that the usage of

nine squares in architectural plans and

garden layouts has been an old tradition in

India with its ultimate source in ancient

mythology. Arabian mathematicians inte-

grated this Indian system into their own

synthesis of ancient systems." They utilized

squares based on the use of numerals 1 to 9,

in which numerical relationships reveal

characteristic visual patterns (Figures 13 and

14). Throughout the history of ideas we find

constant reference to mathematics as an

aesthetic; to the recognition of fundamental

orders, sequences and patterns. The square

formed on a nine-by-nine grid numbered

1 to 9 horizontally and vertically as illus-

trated, was the basis of a whole mathematical

system, which contained a numerical model

of the universe. Architecturally, the sub-

division of a square space into nine equal

squares offers the privileged use of the

central space, maintaining an implicit visual

relationship with its surround.

One of the most outstanding, and perhaps

the first, buildings in Akbar’s time is the

Garden Tomb built for his father—

Humiyua, supervised by Akbar’s mother—

Hameeda Begum; this is to-day an imposing

Figure 12. Town layout based on a modular grid

town layout on the nine-square arrangement

is the eighteenth-century Rajpit city of

Jaipur. The Rajas of Ambér were in close

contact with the Mughal court because of

marriage alliances, and there was a constant

cultural exchange that reveals itself in many

Mughal and Rajpiit practices. Nevertheless,

when Raja Jai Singh decided to build his new

city he leaned heavily on the scriptures for

its layout and extent (Figure 16).

Even though the nine-square grid has

formed the basis for the town plans for both

Fatehpur Sikri and Jaipur, unlike Jaipur,

Sikri does not have a grid plan. While it uses

the grid for siting most of its important land-

marks, its street system does not adhere to a

grid pattern and its palaces are influenced by

a variety of other factors, including the

Mecca orientation of the Mosque and the

topography of the ridge. Sikri seems to grow

from the site, its surroundings and the

sentiments associated with it. Jaipur on the

other hand is a pre-conceived plan pattern

transferred on to the site rather superficially.

Another capital city which provides an

interesting comparison is Shahjahindbid or

Old Delhi, built by Akbar’s grandson,

Shahjahin, seventy years after the founding

of Fatehpur Sikri. Shahjahandbid was

designed as a city of the same size as

Fatehpur Sikri and a similar design approach

shows that it was influenced by the earlier

concept (Figure 17).

Figure 16. Town plan of Jaipur—

a designed city

Like Fatehpur Sikri, it was also based on

eight super-squares, each comprising of nine

modular squares. The module used in

Shahjahanabad, surprisingly, corresponds to

the one used at’ Sikri, which we know was

obtained in the latter case from the relative

location of its two already existing mosques.

Sited at the bend of the river, the four

corners of Shahjahanabid were cut along

the diagonals of the corner squares. The

super-grid was used to adjust the directions

of the rest of the city walls more or less

symmetrically in both directions, forming a

graceful boat-shape. In both cities the walls

are about five miles long. The location of

most of the city gates is determined by the

super-grid. The citadel has been placed in

more or less similar positions in both cases

and is approximately one-tenth of the city

area. In both cases the palace buildings

were placed in cardinal directions, parallel to

the mosque and inclined at 45° to the direc-

tion of the town grid.

Unlike Fatehpur Sikri, Shahjahan’s citadel

again became a separate entity, separated

from the town by high walls and moats.

Chandni Chowk Bazar and Faiz Bazar were,

however, well related with the palace

complex, till Aurangzeb decided to alter the

axial approach. The Jami Masjid, another

main feature of the city, was sited outside

the citadel walls on a hill site reserved for

this purpose. Splendour was the mood at

Shahjahdnabad, and the city was designed

for formal state processions. Hence the

location of Jami Masjid away from the

citadel placed symmetrically between the

euun hBaSee ua

aa

town layout on the nine-square arrangement

is the eighteenth-century Rajpit city of

Jaipur. The Rajas of Ambér were in close

contact with the Mughal court because of

marriage alliances, and there was a constant

cultural exchange that reveals itself in many

Mughal and Rajpit practices. Nevertheless,

when Raja Jai Singh decided to build his new

city he leaned heavily on the scriptures for

its layout and extent (Figure 16).

Even though the nine-square grid has

formed the basis for the town plans for both

Fatehpur Sikri and Jaipur, unlike Jaipur,

Sikri does not have a grid plan. While it uses

the grid for siting most of its important land-

marks, its street system does not adhere to a

grid pattern and its palaces are influenced by

‘a variety of other factors, including the

Mecca orientation of the Mosque and the

topography of the ridge. Sikri seems to grow

from the site, its surroundings and the

sentiments associated with it. Jaipur on the

other hand is a pre-conceived plan pattern

transferred on to the site rather superficially.

Another capital city which provides an

interesting comparison is Shahjahinabid or

Old Delhi, built by Akbar’s grandson,

Shahjahan, seventy years after the founding

of Fatehpur Sikri. Shahjahandbad was

designed as a city of the same size as

Fatehpur Sikri and a similar design approach

shows that it was influenced by the earlier

concept (Figure 17).

Ficure 16. Town plan of Jaipur—

‘a designed city

Like Fatehpur Sikri, it was also based on

eight super-squares, each comprising of nine

modular squares. The module used in

Shahjahanabad, surprisingly, corresponds to

the one used at’ Sikri, which we know was

obtained in the latter case from the relative

location of its two already existing mosques.

Sited at the bend of the river, the four

corners of Shahjahanadbad were cut along

the diagonals of the corner squares. The

super-grid was used to adjust the directions

of the rest of the city walls more or less

symmetrically in both directions, forming a

graceful boat-shape. In both cities the walls

are about five miles long. The location of

most of the city gates is determined by the

super-grid. The citadel has been placed in

more or less similar positions in both cases

and is approximately one-tenth of the city

area. In both cases the palace buildings

were placed in cardinal directions, parallel to

the mosque and inclined at 45° to the direc-

tion of the town gri

Unlike Fatehpur Sikri, Shahjahan’s citadel

again became a separate entity, separated

from the town by high walls and moats.

Chandni Chowk Bazar and Faiz Bazdr were,

however, well related with the palace

complex, till Aurangzeb decided to alter the

axial approach. The Jami Masjid, another

main feature of the city, was sited outside

the citadel walls on a hill site reserved for

this purpose. Splendour was the mood at

Shahjahanabad, and the city was designed

for formal state processions. Hence the

location of Jami Masjid away from the

citadel placed symmetrically between the

twa h&vSre wae inet rioht and. annranrijare.

Froure 18, Location of Jami Masjid and Imperial household on

‘Sikri ridge determined

Fiaure 19. The geometrical location of the Seat of Throne

(Aurang Chhatr)

Ficure 18. Location of Jami Masjid and Imperial household on

‘Sikri ridge determined

Ficure 19. The geometrical location of the Seat of Throne

(Aurang Chhatr)

services, workshops and stores for the palace

were placed around the central core and

were accessible from an outer road.1* The

day guards and night guards would form

another outer ring, protecting the royal

enclosures and their services. More space

was reserved at the back to accommodate

female attendants and maids for the royal

occupants. This overall arrangement must

have formed the basis for the planning of the

palace precinct. There were, of course,

several other site conditions to reckon with.

The ridge was narrow for the usual space

requirements of the royal enclosure in a

camp. It commanded an excellent view of

the lake in the north-east that was artificially

created for the purpose (it brings to mind

a similar situation successfully met in

Chandigarh in our own times) and it was

all happening against the backdrop of the

great Jami Masjid.

The palace courts were laid out parallel to

the mosque, and the four enclosures fitted

Ficure 22. Nakshd-i-Ain-i-Mansil (Sketch

‘of Camp Order) in the Court chronicle

“Ain-i-Akbari?

inter-locking axial system creates an ordered

composition inducing a relaxed mood and

pleasure of movement, so perceptively

analysed by Jacqueline Tyrwhitt.!° The

changing levels of various courts based on

the slope of the ridge was used imaginatively

to control the flow of running water. Finally

it would collect in the huge reservoir,

ninety feet by ninety feet, and thirty feet

deep. Breeze-catching pavilions were built

‘on its wide retaining walls, enjoying a

panaromic view of the lake. The movement

about these courtyards is a feast for the

senses and heightens that sense of participa-

tion in a great drama of life (Figure 25).

The narrowness of the ridge at certain

places led to the extension of some of the

terraces and platforms beyond its edge,

making it necessary to build supporting

structures under them. The situation led to

several functional as well as aesthetic

advantages (Figure 26). The supporting

structures were ideally suited for the

Fiaure 23. The four royal enclosures were

arranged axially in order of increasing privacy

and security. Service areas and security

‘guards formed outer rings

iw material irom the street level, and alter

processing delivering them at the top level

for consumption, seems like an efficient

arrangement based on economy of move-

ment. Besides, it lent itself to quick and

regular royal supervision—an essential part

of Akbar’s daily routine. It was particularly

important for the extensive kitchen depart-

ment to be reasonably near. Working on a

perfection scale all the buildings for the

royal use were placed carefully parallel to the

Jami Masjid, while service buildings, for

reasons of economy, were placed along the

contours of the ridge. The combination

produced many unusual, irregular open

areas around the palaces which were linked

together by gateways to provide access to the

Diwan-i-Am and Mahal-i-Khas (the Royal

Residence). The space volumes obtained in

this manner are very contemporary in sp’

It reminds one of Louis Kahn’s way of look-

ing at the streets as a series of open rooms.

The Utopian images of the two most

Ficure 24. (Below, left) Royal areas in dressed red sandstone were laid out parallel to the mosque,

while service areas in grey quartzite followed the contours

Ficure 25. (Above, right) Terrace plan showing the relationship of interconnected courts

Ficure 26. (Below, right) Alll factors synthethized into a space-setting offering visual drama and

‘frequent change of scene

FIGURE 27. Chishti mosque serving as a movement focus

influenced the street layout

Ses Sree Oe

beginning of the royal area

poememnariisipecntest

FIGuRE 30. View of this

novel structure, called

Diwan-i-Khas (with most

unusual interior space),

from Akbar’sKhwabgah (Bed

chamber). (Photograph by

courtesy of the Department

of Archaeology, Government

of India)

Tur

|

The feel of the site, open vista and open | guards’ rooms, stables and water tanks as

character of the citadel, its diagonal place-

ment to the ridge, wide ramps and high gate-

ways for elephant movement (Akbar had

110 elephants for personal use), along with

Akbar’s temperament, contributed to the

dramatic character of most of the palace

approaches from the north-east of the ridge

(Figure 31). The gates and enclosures on the

other side disappeared, being closer to the

town. The inter-linked courts with grand

ramps and controlled vistas provide a space

setting in which every rise in level offers a

surprise and a complete change of scene.

Unfortunately these approaches are an im-

possible experience now as their connections

with the palaces have been completely

severed during recent years.!®

The government’s decision, about eight

years ago, to collect entrance money from

the tourists visiting the monuments has led

to a system of entry control which, it seems,

made it necessary for the Archaeological

Survey to close most of the palace gates and

outside areas. This unnatural separation of

the monuments has proved most unfortunate

in many ways. First of all, it deprives visitors

of the opportunity of fully experiencing the

palaces by using different gates for entering

or leaving them. It obscures the function of

many inside areas, e.g. the Purdah Passage,

where continuity was an important con-

sideration. The open character of the city,

which was its chief characteristic, has been

completely destroyed. Since one has to go a

Jong distance around the walls to visit out-

side areas, most tourists cannot visit them in

a short stay. Since these are not visited much

now, even the site engineers and mainte-

nance men have lost their interest in them.

It did not take the town long to encroach on

these areas: new structures have been put

up, new roads made for individual use, and

free use made of stones that were lying

scattered around. These happenings could

not be checked by the Survey very effectively;

its own labour gangs quite carelessly dug up

FIGURE 32.

tro WATHT POL

Sketch of Sikri ridge from Bharatpur Road showing

two important approaches to the monuments

ruins of the Jauhri Bazar to widen the

existing road and to build a bigger car park.

In this context the last decade was mostly

the unmaking of Fatehpur Sikri. Mention

of deteriorating monuments at Sikri did

seem to disturb many in the government,

but unfortunately we are still losing

Fatehpur Sikri very fast every year.

Many beautiful monuments located near

system is totally inadequate. Some of the

gates in the city walls present a panoramic

view of the palaces from advantageous

angles, but they are so inaccessible by car

that very few people can get up there. From

Gwalior Gate in the south-east, one gets a

grand view of the imposing Buland Darwaza,

dominating the whole countryside. The

stepped up city wall across the hill in the

distance looks very sculpturesque from this

point. Nearby is Todar Mal’s!? octagonal

pavilion, which once stood in an extensive

garden. Not far from here, outside the

‘Tétha Gate, is Bahdu-ud-Din’s Tomb.

Bahdu-ud-Din was the Superintendent of

Works, responsible for the construction of

the city. This pleasant little tomb lies |

neglected, unkown and unvisited.

The best view of the ridge and the royal

palaces can be obtained from the Bharatpur

Road (Figure 32). The long lines of palaces

with their domes and pinnacles can be seen

from a distance of several miles as you drive

towards the city. An approach road from this

side could lead the visitors either straight to

the Diwdn-i-Am or to the Hathi Pél

(Elephant Gate) entrance on the other side. |

Both these entries are a rewarding experi-

ence, and need to be developed with due

care and consideration. The complete road

system at Fatchpur Sikri needs to be re-

viewed afresh, considering the ever-increas-

officials on their routine visits to the monu-

ments. These roads cutting through the

preserved courtyards must be discontinued

and a circulatory road built instead which

approaches the monuments from several

directions without disfiguring them, and

without causing inconvenience to the

pedestrian experience.

With greater thought and careful survey

it should be possible, without interfering

with the life of the town, to introduce a road

system which would cover a much larger

area and bring all the scattered monuments

within the reach of the tourists. The implicit

visual energies of the town need to be

augmented by a movement pattern based on.

a sympathetic perception of the monuments,

their functions and the sensitivity of their

placement. Carefully handled, Fatehpur

Sikri can assume an entirely new dimension

by enabling visitors to experience Akbar’s

dream city objectively as a meaningful

sequence.

The first step in this direction is to check

the disruptive forces at all levels that are

causing the present unmaking of this unique

historical heritage and to stop all arbitrary

decisions that are eroding the very principles

of this magnificent townplan. That is the

very least that we can do towards the making

of Fatehpur Sikri.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to Mr. Din Dayal Parashar,

Municipal Commissioner, Fatehpur Sikri,

for showing me around some of the old parts

of present Fatehpur town. His brother, Mr.

Murari Lal Parashar, very kindly enabled

me to examine several old documents and

drawings in the family possession. Special

thanks are due to Mr. Krishna Ailawadi for

his help in the preparation of graphic

material, and to Miss Anne Upsom for

here that the basic theme of this paper was

first presented at Fatehpur Sikri in Decem-

ber 1972, in a Seminar sponsored by the

Department of Archaeology, Government of

India, to celebrate the gooth anniversary of

the founding of Akbar’s Fatehpur. I am

grateful to the Department for making this

participation possible and for extending

other courtesies from time to time, which

have greatly helped in further investigations.

GLOSSARY

Ain-i-Akbari_ ‘Law and Regulations at Akbar’s

‘Court’, compiled by his Court Chronicler and

close associate Abul Fazal.

Aurang Chhatr The royal throne with its

overhead ornamental pavilion.

Badshahi_ King’s; royal.

Buland Darwaza Lofty gateway built in the

south wall of fami Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri.

Chishti The Chishti dervish order (si/sild) was

introduced into India by Khwaja Muin al-Din

Chishti of Ajmer (1141-1236) and rapidly

established a reputation for sanctity.

Diwan-i-Am Court of public audience.

Diwan-i-Khas Hall of private audience.

Hammam Baths.

Hat Pardo Market for the camp.

Hathi Pol Elephant Gate.

Wéhi Gaz A unit of measurement of Akbar’s

time.

Jami Masjid Principal mosque for

assemblies—especially on Fridays,

Kaérkhandjét Plural of kirkhin’; meaning

workplace. Service areas and production

centres.

Khwabgah Bed chamber.

Lédi_ An Afghan tribe.

Mahal-i-Khds ‘The Emperor's private apart-

ments.

Masjid-i-Sangtrashén —Stone-cutters’ mosque.

Mir Manzil The Superintendent of Encamp-

ment.

Nakshd-i-Ain-i-Manzil Sketch of Camp Order

as described in Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazal.

Naubat Khana Chowk City square with music

gallery to announce royal arrivals and

departures and other important hours,

Pardo Halt; stay; army camp or royal camp.

Pathan A people inhabiting the hilly country

to the north-west of Lahore; a soldier; a

warrior; the Afghan race.

Pukhté Strong; permanent; (a structure) made

of baked brick or stone.

A Hindu equivalent to a king,

‘a0 Baas

large

en

GRRE WIRUS SOUS, UUIN equenay U7 Va

kings.

Shahjahdndbdd Present Old Delhi; new capital

built by Shahjahan when he moved from

Agra to Delhi.

Shaikh A Muslim saint or scholar.

Sikri Abode of Sikarwirs.

Sikarwar A Rajpit tribe

Safi A Muslim mystic; a dervish.

NOTES

1. Vincent A. Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul 1542-1605,

New Deihi, 1962, pp. 77. ‘Agra and Fatepore are two

Yeo great ‘ites, either of them much greater than

London and very populous. “Between “Agra and

i

Fat ~ sald

Hertha adit aaa eat

Pint vai tae a

nathan Be sseription by Rete Fitch, Seprember 5

market Description eprember 1585.

Pitter) af India, Vol. 1, New Dealt,

a ee ee Lek, Nal de Cat ta

lant ‘were orepared, srtizans summoned. from all

arte of his dominion, and the work pushed on with

Puch lightning rapidity that not only its. splendour

‘but the almost magical speed with which it wat

completed was a matter of contemporary exmament!

B.D, Sanwaly Agra and itr Monuments, 1988, 0p.

For detail of the Chi Mi household. see tay ari

Tin Bate le Saved?» Design incor.

grating Ind ‘indian Bader, April 1973, BD

4. he Sitarwar Citadel da the adjoining bil north-east

of Fatehpur hae been completely chitclled down by

4 large number of stone-cutters working on it for the

last seven years. Its last remnants are two Bdolis

(stepped wells) which still exist ina rather dilapidated

sondition in the north-west and south-east of this

iil: ‘These’seem ‘to be part of the water Supply

system which once served this citadel,

Stanley Lane-Poole, Babar, New Delhi, 1964, p. 169.

Recently the courtyard walls of this ‘mosque have

been used for the extension of @ neighbouring flour

mail. Left unchecked, this encroachment would soon

‘endanger the existence of this structure.

7. Parts of this road can be seen in the old revenue maps

of Fatehpur Sikri,

8. Awell in the north-east of this gate was covered and

‘concreted some years ago to make room for the new

municipal offices built there. ‘This well fulfilled the

needs of the occupants of this Sardi and also supplied

the great public Hammdm situated between this gate

and the Buland Darwdsd. |

9. Br. Chast, basing his calculation on the discovery

manuscript ives measurements of the Ta)

i ‘gees defings 1 pon ee caual wo O79 mewen, Le.

I

inches.

ro. Keith Albar, Jenny Miall Smith, Stanford Steele,

Dinah Walker, The Language of Pattern,

1974, pp. 10-12.

11, Minutely observing Mughal miniatures, Bllen Smart

Presents an. illustration from EP Baburt

Galnted in "Akbar's time) showing ‘Bibur and his

rchitect discussing the plan of Bagh-i-Wa/d. Babur

is pointing with his right hand at the plan and three

of the gardeners stretch, rope to check the position

of the waterway. ‘Smart convincingly

gn cobarged Geval that tas plon hes lunes drawn to

form a gnd. :

See B'S" Smart, ‘Graphic Evidence for Mughal Archi-

tectural Plans’, AARP (Art and Archaeological

Research Papers), 6, London, 1974, Bp. 22-3.

forhuls, pp.

a, Willi Tevine, The Army of Indian

109

13. Abul Fazal Allimi, Aini-Akbori, tans. H. Bloch-

ann, Delhi 1965, Plate IV and np. 49-5

14. For a detailed account of service “areas, see_my

acl, “Imperial Workshop at Fatehpur Sikri—The

Royal Kitchen AARP 5, Bn, 28-41-

Is. J, Tyrwhitt “The Moving Eye’

6. See amy artcks, "Ber indkee Rreeacolosisy Ki

16. article, india's’ Archaeologists Know

whe Ener ‘Are Dot

Fatehpur Sut, Den

Incorporating’ Indian ‘Builder, New Delhi,” March

tre te aanee, —

oe

& Explorations in

ee ee ee eee

of times, but Mr. Davar has shown me how

relatively little I do know and what an enormous

amount there is still to know. I can hardly wait

t0 go back there, and look again with the insights

he has given us this evening.

Mr. Oscar Davies: Why was the city

abandoned after fifteen years ?

‘THE LECTURER: It seems that there were

several personal, political and cultural factors

which must have contributed towards this. In

the first instance, the very circumstances that

led to this speedy undertaking lost their validity

over the years. The new city was a way of

celebrating the birth of Prince Salim. It was a

way of acknowledging the divine blessing and

the good luck that the place had brought. ‘This

initial fondness for the place must have even-

tually become a sore point for Akbar, who at a

later stage became seriously concerned about the

habit and attitude of the young prince. In this

growing antagonism, the king must be resent-

fully aware of the natural sympathy and unex-

pressed loyalty of Chisht! household for Prince

Salim, who had grown up with Chishti grand-

sons from carly childhood. This is just one

aspect. Shaikh Chishti, whose presence initially

inspired the project, died soon after.

After a decade at Sikri, Akbar was passing

through the most critical period of his reign.

His involvement in the famous religious debates

at Sikri eventually led him, step by step, to

assume all powers of a religious head. Then he

introduced a new religion, which in spite of

subtle pressures, was not accepted by most of

his close associates. This must have resulted in

a deep sense of personal defeat at that moment,

in spite of compensations provided by success in

other areas. Intelligence reports about a planned

rebellion at this time must have caused some

uneasiness. There was trouble in Bengal on one

end, and his cousin Mirza Hakim in Kabul on

the other end, had ambitious plans to take

advantage of the situation. An army march to

Kabul kept Akbar away from Sikri for about a

year. Around this time, severe floods in Stkri

caused havoc, disrupting many services. The

fact that these services were never fully restored

suggests that Akbar was already disillusioned

with this place. Later, suspected danger from

Badikashin made it necessary for him to stay

on in Lahore, which was also more suitable for

extending the empire northwards and west-

wards. In history it is not at all uncommon for

kings to shift capitals to new geographical

centres close to areas of ity. In the case of

Sikri, however, since it was a young city, this

Ot tl Ps

Sn

I do not accept the view put forward by some

historians that the city was abandoned for ever

because of an unexpected shortage of water.

Mr. REGINALD Massey: Is it known whom

the architects employed were? Were they

Indians? Were they Hindus, or Muslims from

Iran ? Also, is there any indication of the size of

the labour force employed ?

‘Tue Lecturer: There is no definite informa-

tion about the architects employed. Kasim Khan

was Akbar’s chief engincer for building the fort

at Agra and is mentioned here and there in other

contexts. There is a small tomb at Sikri outside

the town wall—between the palaces and the

quarries. It is called Bahau-ud-Din’s Tomb.

Bahdu-ud-Din is traditionally believed to be

Superintendent of Works, pethaps responsible

for the mosque and palace complex. As the

citadel arose with great speed, a large number of

master builders and craftsmen from all over the

country contributed here. Many provincial styles

can be seen at Sikri side by side, and prominent

among these is that of Gujarat. It has not been

estimated, so far, how many pcople were em-

ployed for the job.

Mrs. Marjorie Gator: Did the aban-

donment of the city seem a very dramatic event

at the time ? Did it have any impact on literature,

were there lamentations for the abandonment,

or was it more or less written off?

Tue Lecturer: It is a very fascinating

question. There are references to the aban-

doned city in some travelogues, but I have not

come across, so far, any lamentation or personal

sorrow expressed in the poetry or prose of the

time.

Mr. Derick Garnier: Whether or not one

believes that there was a shortage or failure of

water at Sikri, there certainly was a very exten-

sive system of plumbing. Would Mr. Davar like

to say something about the water system, its

creation and preservation ?

Tue Lecturer: There was indeed a very

elaborate water supply system for the palaces and

most of it is in an excellent state of preservation.

As the city was built, a large lake was created in

the north-west, which must have helped in soil

saturation, as a large number of wells were built

by the people. Two large reservoirs were built

near the palaces on the two sides of the ridge.

Persian wheel system was used to pull water to

the palace level in three stages. The flow would

then be directed through garden canals, tanks,

decorative channels, fountains, etc., using the

natural slope of the hill and the varying levels of

anlar marie on mailers oll olan eeawem to, chun oun

and dry climates depend on nature and on rains

to some extent.

‘Tue Cuarrman: Is it known whether the

abandonment of the city happened to follow a

number of years when there was a bad mon-

soon? Is there a record of the years when the

monsoon was good ?

‘Tue Lecturer: If does not seem likely that

the abandonment of the city was caused by |

failure of monsoons. On the other hand, several

contemporary references mention the floods

caused by the outburst of the lake dam a little

before its abandonment. These floods, caused

possibly by heavy monsoons, damaged many

services at the foot of the ridge. It could not

have been very difficult for Akbar to restore

these areas to their normal functioning, but it

seems he was fast losing interest in this place

because of various stresses mentioned earlier.

Mr. ROBERT SHAW: May I ask Mr. Davar if

he could place the building of Fatehpur Sikri in

relation to the Forts at Agri and at Delhi. Which

came first? They were also built by Akbar, I

think,

Tue Lecturer: The fort at Agra comes first.

It was more or less near completion when the

building of the Jami mosque and the palace was

started at Sikri. After twelve or thirteen years,

Akbar started building another fort at Allahabad,

but that project was not pressed with speed, and

was later abandoned in favour of Lahore fort.

‘The fort at Delhi was built by Akbar’s grand-

son, Shahjahin, about seventy years after Sikri.

Mr. Massey: J am interested in the inscription

on the main gate which apparently comes from

the New Testament. Could Mr. Davar tell us

which quotation it is? I was also interested to

hear that Akbar, as a born Muslim, should have

insisted on drinking pure water from the holy

Ganges!

‘Tue Lecturer: I am not very familiar with

the New Testament, but the ins

Buland Darwiz4 that you mention is to the

effect that the World is a bridge; pass over it but

do not build on it. It is interesting that Akbar

had this quotation inscribed on the tallest build-

ing at Fatehpur Sikri, which was a gateway. The

concept of the World as a bridge appealed to

Akbar’s mind. This should help us in our under-

standing of his complex mental make-up. His

most original and novel building at Fatehpur

Sikri, called Diwan-i-Khas, consists of four

bridges springing from the four internal corners

leading to a central platform, where Akbar sat

up in space and perhaps meditated. On the other

end of the courtyard, in his rest chamber, he

meted an « hich nlerfarm an fanr ealemne | dane and the oreat natenh

quality of the bridge or the space experience it

offers. May be it was the act of bridging itself:

the bridging of the people, the bridging of the

languages and literature and the bridging of the

religions that he attempted in a big way. Akbar

was an orthodox Muslim when he came to

Sikri. Eventually he started experimenting with

practices from other religions as well. Din-i-

ahi or the Divine Religion started by him was

based on many practices adapted from other

religions. His drinking of Ganges water could

be attributed to this.

‘THe CHAIRMAN: One notices in the plans of

Fatehpur Sikri how very wide is the extent of

the walls round the palace area. Was the city at

one time completely built up to those walls, or

were there, inside the walls, fields and farms and

cultivated areas ?

Tue Lecturer: It was customary in Mughal

cities to plan large gardens within the city walls,

as well as outside. Shahjahan’s Delhi, which had

a number of similarities with Fatehpur Sikri,

gives a fair idea of land use distribution at that

time. About one-tenth of the walled area in

Delhi along Chandni Chowk bazar was planned

as gardens. At Sikri, most of the area between

the ridge and the lake in the north-west was

recreational. Many private gardens existed

within the city walls in the south-east. At the

same time, site evidence suggests that the built

‘up area extended beyond the city gate, called

Birbal Pol, in the east and there was population

in the north beyond Delhi gate. This now forms

part of the present village called Nagar.

‘Tue CHarrMan: So the walls marked the

defended area and not the inhabited area ?

THe LectuRER: No, the population did

spread beyond the walls. It was even mandatory

for certain sections of the community to live

outside the town limits.

‘THe CHAIRMAN: The wall was really mili-

tary?

‘THe Lecturer: In this case, it was more a

question of defining the boundary or some kind

of administrative area. The city walls were not

very strong and the palace area again was not

enclosed by high walls. It would seem that the

military aspect was not considered important,

and a much stronger fort at Agra was quite near.

Mr. G. V. CHARLES, FRIBA: Is it possible

that the town can be declared a national monu-

ment to save it from the spoliation taking place ?

Tue Lecturer: Considering thecomplexity

of the situation, the extent of the damage already

nf che mlace whic ic

them off when necessary. similarly some struc-

tures are under municipal jurisdiction. Some

legislation will be necessary before the town can

be declared a national monument. This, how-

ever, should be possible if the respective govern-

ment departments feel strongly concerned about

the situation.

Mr. CuarLes: Is there any movement to

educate public opinion to persuade the govern-

ment to take the necessary measures ?

Tue Lecturer: There is no organized

movement as such. A few articles did appear in

various national newspapers a few years ago.

Design Magazine from New Delhi did a great

deal to persuade the government to take the

necessary measures before it is too late. Several

proposals were made to the Archaeological

Department. Unfortunately there is no organi-

zation or professional body which was com-

mitted to work consistently in this direction.

THe CHAIRMAN: Isn't it to some extent the

result of a shortage of money available in India

for the conservation of historic monuments ?

Tue Lecturer: Generally speaking this is

quite true. And of course any proposals for con-

servation have to be considered within the

limitations of the budget. However, my chief |

concern in this matter are the wrong priorities

and damaging methods that seem to ignore the

historical basis and the design qualities in the

larger sense. Also, looking around the ruins I

am convinced that in many areas lots of results

can be obtained at comparatively very little cost.

‘As an example, in many areas near the palaces

if all the loose stones lying about scattered were

picked up and stacked on the visible plinths, the

plan arrangements would become much more

intelligible and interesting for visitors to look

around. Many other ways can be suggested as

Fatehpur Sikri during a very short period must

have required tremendous organization of

labour. Did Akbar sct up any special machinery

for the construction of the city ?

Tue Lecturer: This is an aspect which is

really remarkable and was very well taken up by

Akbar. Every type of building material—stones,

bricks and woods—were classified and their

prices fixed. Different types of jobs were defined

and wages determined. The weights, the

measures, the specifications, the way to mix the

mortar and plaster and so on, were all recorded

carefully. By personal supervision and keen

interest the king had accumulated enormous

information on building techniques. When work

on Lahore and Agra had hardly finished, he

decided to build a whole large city again. He was

an absolutely passionate builder and had care-

fully worked out every detail connected with his

| building department.

‘Tre CHarrMan: Lam afraid that we have to

draw the meeting to a close, and I am glad that

we end it with Akbar as a passionate builder

rather than on the rather depressing subject of

the deterioration of the fabric. I hardly need say

how fascinating Mr. Davar’s lecture has been,

because the questions asked are the best evidence

of the interest that his talk has aroused. I am

sure many of us will look forward to the oppor-

tunity of going back to Fatehpur Sikri, If any of

us succeed in doing so in the next few years and

find people poking around outside the conven-

tional tourist area, I think we will know where

some of them got the incentive! I thank Mr.

Davar for a splendid lecture.

The meeting concluded with the usual acclama-

tion of the Lecturer and Chairman.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Indian Painting 1450 1850.Document45 pagesIndian Painting 1450 1850.Shivansh Kumar100% (1)

- Ground Floor Plan: ToiletDocument1 pageGround Floor Plan: ToiletShivansh KumarNo ratings yet

- Shivansh 2 PDFDocument1 pageShivansh 2 PDFShivansh KumarNo ratings yet

- 2bhk PDFDocument1 page2bhk PDFShivansh KumarNo ratings yet

- Works of Laurie Baker: Pesented By:Rashi Chugh Studio 3-B SsaaDocument31 pagesWorks of Laurie Baker: Pesented By:Rashi Chugh Studio 3-B SsaaShivansh KumarNo ratings yet