Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Truth, Justice and Reconciliation

Uploaded by

Adrian MacoveiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Truth, Justice and Reconciliation

Uploaded by

Adrian MacoveiCopyright:

Available Formats

Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation: Judging the Fairness of Amnesty in South Africa

Author(s): James L. Gibson

Source: American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46, No. 3 (Jul., 2002), pp. 540-556

Published by: Midwest Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088398 .

Accessed: 03/02/2014 17:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Midwest Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Journal of Political Science.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation:

the Fairness of in South Africa

Judging Amnesty

James L. GibSOII Washington University in St. Louis

Nations in transition to democratic of the most difficult challenges facing transitional regimes is

governance often must address the the problem of the past. Regimes undergoing transitions from

political atrocities committed under One dictatorial to democratic government are often faced with dealing

the ancien regime. A common re- with their histories, in one form or another, since it is rare that those who

sponse is some sort of "truth commis- fought for and against democratic change are willing to simply "forgive and

sion," typically with the power to grant forget." How new regimes deal with the past has much to do with the likeli-

amnesty to those confessing their hood that their democratic transitions will be successfully consolidated.

Based on a survey of the

illicit deeds. One method of addressing the past is through granting amnesty to

South African mass public, my pur- those who committed crimes during the transition. Especially when the

pose here is to investigate judgments struggle for political change produces no unequivocal winner, negotiation

of the fairness of amnesty. I employ characterizes the transition. One of the key points under negotiation is of?

an experimental "vignette" to assess ten accountability for the abuses of the past. Countries throughout the

the contributions of various forms of world have established processes through which amnesty may be given to

justice to judgments of the fairness of the combatants in the transitional struggle in exchange for truth, reconcili-

granting amnesty. My analysis indi? ation, and acquiescence to the new political order.

cates that justice considerations do But amnesty does not come without a price. One important cost is that

indeed influence fairness assess- expectations of retribution are unsatisfied. To the extent that amnesty con-

ments. Distributive justice matters? tributes to unrequited expectations for justice, a justice deficit may be cre?

providing victims compensation in? ated for the new authorities, with the possibility that the new regime and its

creases perceptions that amnesty is institutions will be deprived of life-giving legitimacy.

fair. But so too do procedural (voice) Nowhere is this problem of amnesty and justice more acute than in

and restorative (apologies) justice South Africa. During the transition, the leadership of the African National

matter for amnesty judgments. I con-

clude that the failure of the new re?

gime in South Africa to satisfy expec- James L. Gibson is Sidney W. Souers Professor of Government, Department of Political

tations of justice may have serious Science, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1063,219 Eliot Hall, St. Louis,

MO 63130-4899 (jgibson@artsci.wustl.edu).

consequences for the likelihood of

This is a revised version of a paper delivered at the 59th Annual Meeting of the Midwest

successfully consolidating the demo?

Political Science Association, April 19-21,2001, Palmer House Hilton, Chicago, Illinois.

cratic transition. The research is based on work supported by the Law and Social Sciences Program ofthe

National Science Foundation under Grant No. SES 9906576. Any opinions, findings,

and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author

and do not necessarily reflect the views ofthe National Science Foundation. The project

is a collaborative effort between Amanda Gouws, Department of Political Science, the

University of Stellenbosch (South Africa), and me. I am indebted to Charles Villa-

Vicencio, Helen Macdonald, Paul Haupt, Nyameka Goniwe, Fanie du Toit, Erik

Doxtader, and the staff ofthe Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (South Africa),

where I am a Distinguished Visiting Research Scholar, for the many helpful discussions

that have informed my understanding of the truth and reconciliation process in South

Africa. Eric Lomazoff provide valuable research assistance on this project. I am also

thankful to James Alt, Ronald Slye, and John T. Scott for comments on an earlier version

of this article. Finally, I very much appreciate the advice and assistance provided by

Kathleen McGraw on many aspects of this article.

American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46, No. 3, July 2002, Pp. 540-556

?2002 by the Midwest Political Science Association ISSN 0092-5853

540

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 541

Congress (ANC) made a Faustian bargain in order to se? and generalizability). By assessing the efficacy of different

cure majority rule in a democratic South Africa (de forms of justice motives, this article seeks to contribute

Lange 2000,17-18). The ANC traded amnesty for peace; to a more general understanding of the role of justice

the leaders

of the apartheid government accepted free- considerations in the political judgments of ordinary

dom from prosecution for human rights abuses in ex? South Africans. I begin with a brief review of South

change for power sharing. The bargain succeeded?the Africa's truth and reconciliation process.

ANC acquired power through peaceful and legitimate

elections, and few if any white South Africans have been

punished for the misdeeds of the apartheid system. The

desire of many if not most South Africans for justice? Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa

including some sort of reconciliation with the past?

continues to play a significant role in contemporary One of the central issues in the talks over ending apart-

South African politics. heid in South Africa was amnesty. In South Africa, in

My purpose here is to investigate the importance of contrast to other nations emerging from a tyrannical

justice expectations for the South African transition. I fo- past (e.g., Argentina and Uganda), the ancien regime was

cus on the truth and reconciliation process, and in par? not defeated; consequently the transition was brokered.

ticular on amnesty. I begin from the premise that grant? The National Party and the leaders of other powerful

ing amnesty to those who have admitted gross human white-dominated institutions (e.g., the security forces)

rights violations is an inherently unfair policy in the made amnesty a nonnegotiable centerpiece of their de-

sense that evil deeds seem to be excused, if not rewarded. mands (see Omar 1996). The creation ofthe Truth and

Amnesty seems to make retributive justice elusive, if not Reconciliation Commission, with the power to grant am?

impossible. This researchasks specifically whether other nesty, was the price the liberation forces had to pay in or?

forms of justice can compensate for this apparent unfair- der to secure a peaceful transition to majority rule

ness, rendering amnesty less difficult for South Africans (Rwelamira 1996).

to stomach. The parliament granted the TRC the authority to

The compensatory justice contemplated by those give amnesty to acts motivated by political objectives.1

who created the truth and reconciliation process is pri- Those whose actions were committed for personal gain

marily distributive?those who came before the Truth or out of "personal malice, ill will or spite" were not eli-

and Reconciliation Commission (the TRC) and told their gible for amnesty.2 Those seeking amnesties are to be

stories of abuse were promised at least some compensa- judged by their motives, whether the act was associated

tion for their injuries. But other forms of justice may be with a political uprising, the gravity of the offence,

important as well. For instance, many argue that the op- whether the act was "committed in the execution of an

portunity for the victims and their families to discuss order" issued by an "organisation [sic], institution, lib?

their injuries publicly (a form of procedural justice) has eration movement or body of which the person who

done much to defuse anger over the granting of amnesty committed the act was a member, an agent or a sup-

to perpetrators. No one knows, however, whether alterna- porter" (National Unity and Reconciliation Act, 1995

tive forms of justice?including nondistributive forms? (20) (3) (e)).

can ameliorate the apparent affront of failing to get at The amnesty process was certainly controversial,

least some degree of vengeance against those who have with many (including Amnesty International) arguing

admitted to engaging in gross human rights violations. that international law and convention forbade granting

Thus, my purpose here is to examine the judgments amnesty to crimes against humanity. Nonetheless, the

ordinary people make about amnesty, testing hypotheses

about whether four types of justice perceptions?dis?

tributive, procedural, retributive, and restorative?influ? ^ayner (2000, 33) distinguishes the South African truth and rec?

onciliation process in the following ways: "a public process of dis-

ence assessments of the fairness of amnesty to those who

closure by perpetrators and public hearings for victims; an am?

were victimized by the amnesty applicants. These hy? nesty process that reviewed individual applications and avoided

potheses are grounded in extant literature on the psy- any blanket amnesty; and a process that was intensely focused on

national healing and reconciliation, with the intent of moving a

chology of justice. I test these hypotheses through an ex-

country from its repressive past to a peaceful future, where former

periment embedded within a nationally representative opponents could work side by side."

survey of roughly 3700 South Africans, conducted in

2Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, 1995, (20)

2000/2001. As a consequence, this research has strong

(3) (f) (ii). The text of the act is available at http://www.truth.org.

claims to both internal and external validity (causality za/legal/act9534.htm [accessed 9/17/2001].

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

542 JAMES L. GIBSON

South African Constitutional Court passed on the consti- Theories of Justice and

tutionality of the act (Azanian Peoples Organization Reactions to Amnesty

(AZAPO) and others v. President of the Republic of

South Africa and others 1996 (4) SALR 671 (CQ), and

The research literature suggests that four types of justice

the TRC began functioning in 1995.

may be relevant to how ordinary South Africans perceive

The TRC received roughly 20,000 statements from

and evaluate amnesty as provided for in the truth and

victims and their families and approximately 7,000 ap- reconciliation process. The most obvious of these has to

plications for amnesty.3 As of November 2000, the TRC do with compensation for the victims and their families,

had granted 849 amnesties, but rejected 5,392 appli-

or distributive justice.

cants. The most common reason for denying an appli-

cation is that no political motive was attached to the

action for which amnesty was sought.4 Some of the am? Distributive Justice

nesties granted were in highly visible cases (e.g., the

Those who designed the amnesty process placed a great

murder of Amy Biehl).5

deal of emphasis on compensating the victims of apart-

The release of the "Final Report" of the TRC on 29

heid for their losses. For instance, the TRC Final Report

October 1998 generated a new storm of controversy and

asserts: ". . . in the context of the South African Truth

protest over the Commission and its activities, from ev-

and Reconciliation Commission, reparation is essential

ery quarter, including the ANC (see for example Ngidi to counterbalance The

amnesty. granting of amnesty de-

1998, and generally the Spring 1998 issue of Siyayal).

nies victims the rights to institute civil claims against

Debate continued through the end of 2000, focused

perpetrators. The government should accept responsi-

mainly on the issue of providing compensation for the

bility for reparation" (Truth and Reconciliation Com?

victims who came forward to tell their stories. Many be-

mission 1998, Volume 5, 170, emphasis added). From

lieve that the truth and reconciliation process continues

the beginning of the process, most expected that mon?

to be an important source of dissatisfaction with the

etary reparations would be paid by the government (see,

current Mbeki regime.

for example, Daniel, 2000,4). Though the government

Addressing human rights violations under the apart? has provided limited interim reparations,7 by 2001,

heid regime has been a painful one for South Africa.6 The

criticism of the government for failure to provide com?

amnesty hearings have revealed atrocities almost beyond became increasingly and even

pensation widespread

belief (e.g., de Kock 1998), reopening many old wounds.

virulent.8 The most obvious justice hypothesis is there?

Many South Africans have been appalled that such vi- fore that compensation can correct for amnesty: If those

cious perpetrators should receive amnesty for their ac-

who were victimized receive some form of reparations,

tions (see Gibson and Gouws 1999). But what conse- then perhaps people will judge the truth and reconcilia?

quences flow from the state's failure to punish admitted tion process to have been fair.

miscreants? To answer this question, we need to assess

how a mix of justice considerations might compensate

for the apparent unfairness of amnesty. Restorative Justice

Though the most obvious hypothesis of this research

concerns distributive justice, I also anticipate that expec?

3These statistics are taken from the TRC's Web site (www.truth. tations of restorative justice are important for judgments

org.za), an extremely useful source of information about the pro- of the truth and reconciliation process. Some argue that

ceedings of the commission.

4The Amnesty Committee received a large number of applications

from prisoners serving time for ordinary criminal convictions.

7President Mbeki has asserted that the issue of reparations will be

Most of these applications were judged to be frivolous because no

addressed after the Amnesty Committee of the TRC files its final

political motive for the crime could be demonstrated.

report (in late 2001). The President also said that 16,501 applica-

5In May 2001, President Mbeki dissolved the Amnesty Committee tions for urgent interim relief had been made and that 9,605 had

and formally revived the TRC for the exclusive purpose of adding been acted upon (Mann 2000).

two volumes to its "Final Report." These volumes will address

8See for example, Daniel, who complains about:"... the extraordi-

the experiences of the victims and the work of the Amnesty

Committee. nary meanness the government has displayed to the paying of the

modest and affordable (for the state fiscus) financial reparations

6For a moving account of some of these incidents see Krog 1998. recommended by the Commission to those found to have been

The TRC's web page also reports full details of the atrocities com- victims of apartheid abuse" (2000,4). See http://www.mg.co.za/

mitted by those seeking amnesty. mg/za/archive/2000may/10maypm-news.html#trc.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 543

restorative justice is especially significant in the African 1997). Apologies seem to mitigate blame, and may well

context:9 make the failure to get retributive justice palatable.

Those who designed the truth and reconciliation

In traditional African thought, the emphasis is on process in South Africa chose not to require an apology

restoring evildoers to the community rather than from amnesty applicants, largely due to skepticism about

on punishing them. The term ubuntu, which derives the sincerity of such expressions of regret, rather than

from the Xhosa expression Umuntu ngumuntu doubts about whether sincere apologies would be useful

ngabanye bantu (People are people through other and effective. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that

people), conveys the view that an environment of apologies recognized as sincere ameliorate the negative ef?

right relationships is one in which people are able to fects of amnesty. When sincere apologies are given, I ex?

recognize that their humanity is inextricably bound pect that South Africans will judge amnesty as more fair

up in others' humanity. Ubuntu emphasizes the pri- to the victims and their families.

ority of "restorative" as opposed to "retributive" jus?

tice (Graybill, 1998,47, emphasis in the original).

Procedural justice

Or, as Desmond Tutu has described ubuntu: Also important is the expectation

of procedural justice,11

especially through processes by which victims are given

Ubuntu says I am human only because you are hu? "voice" (Tyler and Mitchell 1994). A great deal of empha?

man. If I undermine your humanity I dehumanize sis can be found in South Africa on the importance ofthe

myself. You must do what you can to maintain this TRC hearings at which victims and their families were

great harmony, which is perpetually undermined by able to come forth and tell their stories (e.g., Orr 2000). As

resentment, anger, desire for vengeance. That's why Justice Mohamed wrote in the Constitutional Court deci?

African jurisprudence is restorative rather than re? sion legitimizing the truth and reconciliation

process:

tributive (Gevisser 1996, quoted in Graybill 1998, "The Act seeks to . . . [encourage] survivors and the

47, emphasis in the original; see also Tutu 1999,54- dependants ofthe tortured and the wounded, the maimed

55). and the dead to unburden their grief publicly, to receive

the recognition of a new nation that they were wronged

When South Africans talk about restorative justice, and crucially, to help them to discover what did in truth

they often refer to processes such as restoring the "dig- happen to their loved ones, where and under what cir-

nity" of the victims (e.g., Villa-Vicencio 2000, 202) cumstances it did happen, and who was responsible"

One important form of restoration involves an apol- (Azanian Peoples Organization (AZAPO) and others v.

ogy.10 An apology can be influential since "an apology is President ofthe Republic of South Africa and others 1996

a gesture through which an individual splits himself into (4) SALR 671 (CC)). In general, the literature on proce?

two parts, the part that is guilty of an offense and the part dural justice suggests that procedure?even apart from

that dissociates itself from the delict and affirms a belief distributive outcomes?can contribute

much to percep-

in the offended rule" (Goffman 1971, 113). A consid- tions of fairness(e.g., Tyler et al. 1997; Tyler and Lind

erable literature in political psychology investigates the 2001). That is one ofthe hypotheses of this research.

effectiveness of apologies in mitigating blame (e.g.,

Ohbuchi, Kameda, and Agarie 1989; see also Vidmar

Retributive Justice

2001, 52-54). Generally, that literature concludes that

apologies can contribute to forgiveness and reconcilia? Recently, increasing attention has been given to the im?

tion under some circumstances (e.g., Scher and Darley portance of retributive justice for political and legal sys?

tems (see for examples Tyler and Boeckmann 1997 and

9The basis of law in much of rural South Africa remains "custom- Vidmar 2001). "Retribution is a passionate reaction to the

ary law,"and restorative justice is a central element in that system. violation of a rule, norm, or law that evokes a desire for

The new constitution did not abolish customary law, even if it did

subordinate it to civil law. For a useful recent analysis see Cham- punishment of the violator" (Sanders and Hamilton 2001,

bers (2000). 6). Retribution concerns the desire of individuals who are

dissociated with the victim or the act and its consequences

10Those writing about restorative justice typically refer to more

than apologies when they speak of restoring dignity of a victim for punishment of offenders and is thought by some to be

and the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator (e.g.,

Kiss 2000). Still, few disagree that apologies are a central element 1!For an excellent review of the literature on

procedural justice, see

of the concept. Tyler and Lind 2001.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

544 JAMES L. GIBSON

"older, more primitive, more universal, and socially more pensation. Since procedural justice was widely seen as

significant" than any other justice feeling (Hogan and such an integral part ofthe truth and reconciliation pro?

Emlerl981,131).12 cess, I expect its influence to rival that of compensation.

The starting point for my analysis is the assumption The law, on the other hand, explicitly rejected restorative

that amnesty subverts retributive justice. Nonetheless, justice (apologies) as a part ofthe process, so I therefore

many have argued that having to make a public confes- expect its influence to be less than that of distributive or

sion of one's dastardly deeds is itself punishment (e.g., procedural justice. Finally, since being relieved of all civil

Tutu 1999, 51-54). For instance, Justice Richard Gold- or criminal penalties for one's gross human rights viola-

stone has asserted: "... the perpetrators suffered a very tions most likely overshadows any subsidiary penalties

real punishment?the public confession of the worst imposed on perpetrators, I predict that retributive justice

atrocities with the permanent stigma and prejudice that will have the smallest influence on judgments of fairness.

it carries with it" (2000, x). Moreover, many perpetrators

experienced other penalties, ranging from having to pay

large fees to their attorneys to receiving condemnations

from their friends and family. Thus, I hypothesize that Research Design

when the perpetrator is portrayed as having experienced

some degree of punishment, South Africans will judge This analysis is based on a survey of the South African

amnesty to be more fair to the victims and their families. mass public conducted in 2000/2001. The fieldwork be-

gan in November 2000,and "mop-up" interviews were

completed by February 2001. The sample is representa?

Summary

tive ofthe entire South African population (18 years old

Thus, the overarching hypothesis of this research is that it and older). A total of 3,727 interviews was completed.

may be possible to compensate for the inherent injustice The average interview lasted eighty-four minutes (with a

of amnesty. If South Africans perceive that the victims median of eighty minutes). The overall response rate for

and their families are given other forms of justice? the survey was approximately 87 percent. The main rea-

procedural, retributive, restorative, and distributive? son for failing to complete the interview was inability to

then amnesty may become a more acceptable part of the contact the respondent; refusal to be interviewed ac-

transitional process. counted for approximately 27 percent ofthe failed inter?

views. Such a high rate of response can be attributed to

the general willingness of the South African population

Justice Priorities

to be interviewed, the large number of call-backs we em-

Ideally, I would be able to deduce from theory the priori? ployed, and the use of an incentive for participating in

ties that individuals attach to each of these forms of jus? the interview.13 Most ofthe interviewers

were females,

tice. Unfortunately, little theory exists indicating when and interviewers of every race were employed in the

one form of justice will become more salient than other project. Most respondents were interviewed by an inter-

forms. From the point-of-view of contemporary politics viewer of their own race. The percentage of same-race

in South Africa, however, it seems likely that distributive interviews for each of the racial groups is: African, 99.8

justice concerns will have the most substantial impact on percent; white, 98.7 percent; Coloured, 71.5 percent; and

attitudes toward amnesty, since the original theory of South Africans of Asian Origin, 73.9 percent.

amnesty was that it would be counterbalanced by com- Interviews were conducted in the respondent's lan-

guage of choice, with a large plurality of the interviews

12Vidmar (2001) and others refer to third-party reactions to moral being done in English (44.5 percent). The questionnaire

wrongs as "disinterested" justice judgments in the sense that was first prepared in English and then translated into Af-

people are concerned about the injustice done to others. This may

occur either through an identification with the victim or through rikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, North Sotho, South Sotho, Tswana,

concern over violations of a "social contract." The latter refers to and Tsonga.14 The methodology of creating a multilin-

judgments that are grounded in concerns for social peace and or?

der and in desires to reaffirm the community's consensus about

13The incentive was a magnetic torch (flashlight), with which the

right and wrong (Vidmar 2001, 42). A bystander may not experi-

ence a direct and tangible injury, but the lack of injury often does respondents were quite pleased. Some research indicates that pro-

not mitigate the moral outrage over the act. Many South Africans viding incentives has few negative consequences for survey re-

sponses (e.g., Singer, Hoewyk, and Maher 1998).

(if not most) were outraged at the human rights abuses revealed by

the truth and reconciliation process, and concern about unfairness 14Manyof the ideas represented in the survey were developed and

to the victims and their families is essentially the same thing as refined by the experience of the focus groups we conducted. In

concern about unfairness to the moral order in South Africa. 2000, we ran six focus groups, involving roughly sixty participants.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 545

gual questionnaire follows closely that recommended by "The TRC has granted amnesties to those who have come

Brislin (1970). Producing an instrument in this many forward and admitted committing atrocities during the

languages that is conceptually and operationally equiva- struggle over apartheid. Do you approve of amnesty being

lent is a very difficult task, and we have no doubt that a given to those who admitted committing atrocities during

considerable amount of measurement error was intro- the struggle over apartheid?" In general, South Africans

duced by the multilingual context in which this research are not opposed to amnesty, with a majority (57.3 per?

was conducted. Nonetheless, we took all possible steps to cent) approving of amnesty to at least some degree.16 Ra?

minimize this error. cial differences are statistically significant (r\ = .30), with

Because the various racial and linguistic groups were black South Africans being far more likely to approve of

not selected proportional to their size in the South Afri? amnesty than those of any other race (71.6 percent of

can population (so as to insure sufficient numbers of blacks approve, with less than a majority of whites,

cases for analysis), it is necessary to weight the data ac- Coloured people, and those of Asian origin supporting

cording to the inverse of the probability of selection for amnesty). It is perhaps a bit surprising that amnesty is so

each respondent. In addition, we have applied post- widely supported among Africans since the most com-

stratification weights to the final data in order to make mon reports about amnesty in the truth and reconcilia?

the sample slightly more representative of the South Afri? tion process generally concerned agents of the apartheid

can population. state being given amnesty for gross human rights viola?

tions they committed against liberation forces.

Race in South Africa Approval of amnesty does not necessarily mean that

one views it as fair, however. We asked whether amnesty

I have already made reference to the major racial groups is fair to four groups: those who died during the struggle

in South Africa? blacks, whites, Coloured people, and over apartheid, the victims, and "ordinary people like

South Africans of Asian origin. Though these categories you." Judgments of fairness vary significantly depending

were used by the apartheid regime to divide and control upon the frame of reference. A large majority of South

the population, these are nonetheless labels that South Af? Africans (72.7 percent) believe amnesty unfair to those

ricans use to refer to themselves (see, for example, Gibson who died in the struggle, and most (65.2 percent) believe

and Gouws 2000). Nothing about my use of these terms it unfair to the victims.Further, a majority (52.6 percent)

should imply approval of anything about apartheid or ac- of South Africansview amnesty as unfair to ordinary

ceptance of any underlying theory of race or ethnicity.15 people, with only 33.5 percent viewing it as fair. On this

question of fairness to ordinary people, racial differences

barely achieve a low level of statistical significance and

the strength of association between race and opinions is

General Views of Amnesty in South Africa = .05).l7 Thus, generally speaking, am?

slight indeed (r\

nesty may be acceptable to most South Africans but its

Before turning to the results of the experimental vignette, unfairness renders it a necessary evil.18

it is useful to consider how South Africans view the am?

nesty process in general. Fortunately, several questions 16The responses to this question were collected on a four-point re-

during the interview addressed this issue. We first asked: sponse: "strongly approve," "approve somewhat," "disapprove

somewhat," and "disapprove a great deal."

15For a more detailed consideration of race in South Africa, see

l7Despite the differences in the univariate frequencies, these fair?

Gibson and Gouws 2002, chapter 2. Note as well that Desmond ness judgments all reflect a single underlying fairness propensity.

Tutu felt obliged to offer a similar caveat about race in South Africa When factor analyzed, a sole dominant factor emerges (and this is

in the Final Report of the TRC. In general, I accept the racial cat? also true when the factor analysis is conducted within the racial

egories as identified by the editor of a special issue of Daedalus fo- groups), strongly suggesting unidimensionality.

cused on South Africa: "Many of the authors in this issue observe

the South African convention of dividing the country's population 18Whywould people approve of amnesty even if they judge it un?

into four racial categories: white (of European descent), colored fair? A full analysis of the responses to these questions is beyond

(of mixed ancestry), Indian (forebears from the Indian subconti- the scope of this article, but it seems likely that many accept am?

nent), and African. The official nomenclature for Africans' has it- nesty because they view it as contributing to the peaceful transi?

self varied over the years, changing from 'native' to 'Bantu' in the tion to majority rule in South Africa. For instance, when asked

middle of the apartheid era, and then changing again to 'black' or, whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

today, 'African/black.' All of these terms appear in the essays that "The TRC was essential to avoid civil war in South Africa during

follow." See Graubard 2001, viii. I use the term "Coloured" to sig- the transition from white rule to majority rule" the percentages

nify that this is a distinctly South African construction of race and agreeing (either "somewhat" or "strongly") with this proposition

"Asian origin" to refer to South Africans drawn from the Indian are: black, 65 percent; white, 18 percent; Coloured, 36 percent; and

Subcontinent. Asian Origin, 47 percent.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

546 IAMES I. GIBSON

In light of the analysis that follows, it is also impor? effort to gain amnesty for crimes he committed under

tant to note that abstract and general judgments of fair- apartheid.21 Each respondent heard only a single story,

ness to the victims and fairness

to ordinary South Afri? and respondents were randomly assigned to vignette ver-

cans are very strongly correlated (r = .56; 0 = .89).19 sions. The manipulations were orthogonal to each other,

None of the other correlations across fairness judgments and the four resulting dummy variables are therefore

is as strong. These findings support the view that judg? uncorrelated. Embedding an experiment within a na-

ments of fairness to the victims are roughly the same thing tionally representative survey yields the substantial ad-

as judgments of fairness to the larger South African society. vantages of both internal and external validity.22

In the analysis that follows, I analyze judgments of

fairness of amnesty to the families of the victims. These

The Structure of the Experimental Vignette

judgments are important since they concern the aspects

of amnesty most likely to be offensive to most South Af? All vignette versions began with the following: "Philip

ricans. The failure of the victims' families to receive any was a member of [the group the respondent dislikes the

sort of retributive justice?since the perpetrator is al- most]. Phillip sought amnesty for setting off a bomb that

lowed to go free after admitting her or his gross human killed several innocent people." We then manipulated

rights violations?is perhaps the most salient and egre- four types of justice in the vignettes.23

gious aspect of the unfairness of amnesty. When South

(1) Procedural Justice: Victims can be given procedural

Africans talk about perpetrators "getting away with mur-

justice by giving them an opportunity to tell their

der" what they mean is that amnesty represents a funda-

story. Research has shown that giving people "voice"

mental unfairness to the victims, and hence to the larger

is the most important aspect of fair procedure (Tyler

society. Because the victims fail to receive justice, society and Mitchell 1994; Tyler et al. 1997), and during the

itself fails to receive justice. Moreover, as I have already

TRC hearings there was much discussion of the ca-

noted, it not fruitful to distinguish empirically between thartic effect of being able to tell one's story publicly.

perceptions of overall fairness and fairness to the victims

Thus, the procedural justice manipulation is:

and their families. Thus, the interesting question ad-

[ 1A.] At his amnesty hearing, the families of the vic?

dressed in this article has to do with how ordinary South

tims got to tell how the bombing has affected

Africans evaluate the fairness of amnesty in terms of its

their lives.

impact on the aggrieved.

[ 1B. ] At his amnesty hearing, the families of the vic?

Of course, these general views are devoid of context.

tims were denied a chance to tell how the

In order to understand the influence of different types of

justice on amnesty attitudes, a different methodology is

necessary.

21We expended considerable effort in finding a racially and ethni-

cally neutral name. In South Africa, "Phillip" implies very little

about the actor, and it is not uncommon to find men named

"Phillip" within every racial/ethnic group. Note that we con-

Analysis sciously decided not to vary the actor's gender, since a very large

majority of the South Africans appealing to the TRC are male.

The Experiment Note that "Phillip" was identified as a member of a political

group that the respondent disliked a great deal, via the "least-liked"

Included in our survey was the Justice and Amnesty technology developed by Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus (1982).

The experimental This insures that each subject was reacting to an amnesty applica-

Experiment. vignette employed four

tion from a member of one of the political groups he or she dis?

manipulations, in what is technically referred to as a

liked a great deal.

2x2x2x2 fully-crossed factorial design.20 That is, four

22The distinction between internal and external validity was first

(dichotomous) characteristics were manipulated, result-

made by Campbell. See for an explication Cook and Campbell

ing in sixteen versions ofthe vignette. This portion ofthe (1979).

interview began with a short story about "Phillip" and his

23Though some ambiguity exists about whether each of these ma-

nipulation exclusively represents these different types of justice?

for instance, compensation might be considered by some to be a

19Only 18.7 percent of the respondents reached opposite conclu-

sions about the fairness of amnesty to the victims and to ordinary form of restorative justice? it is clear that all relevant forms of

people. justice are included in the experiment. Moreover, since the statisti-

cal analysis controls for the other forms of justice, the effects I ob-

20I use the term "vignette" to refer to a short story told to the re- serve are to some degree purified and come to represent each form

spondent. Vignettes nested in surveys have been used widely in the of justice more independently. To avoid confusion, I tend to refer

social sciences?see for examples: Hamilton and Sanders (1992); in the analysis that follows to the variables in more literal than

Gibson (1997); and Gibson and Gouws (1999). conceptual terms.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 54/

bombing has affected their lives, even though fenders as more important than compensating vic?

they had insisted that they wanted to tell their tims?e.g., Hogan and Emler 1981).

story.24 [4A.] Philip was granted amnesty. Afterwards, the

(2) Retributive Justice. Though the amnesty law rules out families of the victimswere given financial

formal retribution, some argue that simply having to compensation by the government for the loss

admit publicly one's crimes is a form of punishment. of their lovedones.

This is especially likely if the admission is associated [4B.] Philip was granted amnesty. Afterwards, the

with some level of shame at what the perpetrator did. families of the victims were not given any fi?

We tried to capture the punishment that a perpetra? nancial compensation because the government

tor might have experienced with the following: says it doesn't have any funding for compen?

[ 2A. ] Phillip then told his version of the bombing. In sating victims. The government did, however,

reaction to Phillip's disclosures, Phillip's family express its sympathy for the families.

says that they are deeply ashamed of what he

Thus, the general hypothesis is that the outcome will

has done, and his wife divorces him.

be judged most fair and the amnesty most likely to be ac-

[ 2B. ] Phillip then told his version of the bombing. In

cepted when the families of the victims were given

reaction to Phillip's disclosures, Phillip's family

says that they understand why he did what he procedural justice?an opportunity to tell their story

did, and that they stand by him. restorative justice?an apology

retributive justice?perpetrator shame and punish?

Throughout the truth and reconciliation process, there

ment

were several well-covered incidents in which perpetrators

distributive justice?compensation

were publicly condemned by their families.

The vignette version I hypothesize to generate the high-

(3) Restorative Justice: The idea here is that the victims

est fairness judgments is one in which all four types of

get something from the process that restores them to

justice are realized:

their status prior to the atrocity. Of course, nothing

can really compensate people for the losses they en-

Philip was a member of [thegroup the respondent

dured under apartheid. But the truth and reconcilia?

dislikes the most]. Phillip sought amnesty for setting

tion process is based, at least in part, on the assump? off a bomb that killed several innocent people. [1A.]

tion that the "dignity" of the victims can be restored At his amnesty hearing, the families of the victims

through the process. Dignity is an amorphous con-

were allowed to tell how the bombing has affected

cept but it may have something to do with apologies. their lives. [2A.] Phillip then told his version of the

The issuing and receiving of apologies establish

bombing. In reaction to Phillip's disclosures, Phillip's

clearly that a wrong has been committed, and creates

family says that they are deeply ashamed of what he

a relationship of equality?however tenuous?be?

has done, and his wife divorces him. [3A.] Philip

tween the victim and the perpetrator. Thus, we in- his

apologized for his actions and apology was ac-

cluded the following manipulation:

cepted by the families of the victims. [4A.] Philip was

[3A.] Philip apologized for his actions and his apol-

granted amnesty. Afterwards, the families of the vic?

ogy was accepted by the families ofthe victims.

tims were given financial compensation by the gov?

[3B.] Philip apologized for his actions but his apol- ernment for the loss of their loved ones.

ogy was rejected as insincere by the families of

the victims.

is the clearest Manipulation Checks

(4) Distributive Justice: Compensation

form of distributive justice, so we manipulated the

Whether each manipulation was actually perceived by

outcome for the family ofthe victim (even in light

the respondents can be assessed through "manipulation

of the general finding that people rate punishing of-

check" questions that parallel each of the experimental

factors. We asked the respondents how certain they are

about their perceptions of various aspects of the stories.

24Not all victims wishing to give public statements at the human

rights violations hearings were in fact allowed to give them. The For instance, the procedural justice check asked: "Do

criteria for selecting who was allowed to speak and who was not al? you think that the families of the victims were given a

lowed varied enormously, and were largely determined by com-

chance to tell how the bombing has affected their lives?"

munity leaders where the hearings were heid (source: conversation

with Charles Villa-Vicencio and Paul Haupt, now at the Institute The response set varied from "certain they were" to "cer?

of Justice and Reconciliation but formerly ofthe TRC). tain they were not." I have reflected the variables so that

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

548 IAMES L. GIBSON

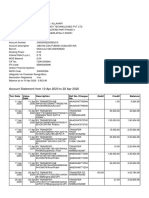

Table 1 Perceptions of the Experimental Manipulations (Manipulation Checks)

aThese two percentages total to 100%, except for "don'tknow"responses.

bThe dependent variable for each manipulationcheck is a five-pointscale, with higher scores indicating greater degrees of certaintythat the action

happened.

cDifferenceof Means test: p = .000; r| = .51.

dDifferenceof Means test: p = .000; n, = .46.

eDifference of Means test: p = .000; ti = .48.

fDifferenceof Means test: p = .000; k\ = .63.

Note: The questions used to check the manipulationsare:

Do you thinkthat the families of the victims were given a chance to tell how the bombing has affected their lives? Certainthey were, Probablywere,

Probablywere not, certain they were not. [Don'tKnow]

Do you thinkthat Phillip'sapology was accepted by the familiesof the victims?Certainit was, Probablywas, Probablywas not, Certainit was not. [Don't

Know]

Do you thinkthat Phillipwas punished by the actions of his own family?Certainhe was, Probablywas, Probablywas not, Certain he was not. [Don't

Know]

Do you thinkthat the families of the victim received compensation for what happened to them? Certainthey did, Probablydid, Probablydid not, Cer?

tain they did not. [Don'tKnow]

higher scores always indicate great certainty. Table 1 re- Fairness Judgments?The Dependent Variables

ports the results of these manipulation checks.

The dependent variable in this analysis is judgments of

The data in this table provide very strong evidence

fairness. We asked: "First, considering all aspects of the

that the manipulations in this experiment "succeeded"

in the sense that they were accurately perceived. Indeed, story, how fair do you think the outcome is to the fami?

lies of the victims?26 The mean fairness scores reveal that

compared to other research based on this methodology

the first vignette?the story in which the family received

(e.g., Gibson and Gouws 1999), the experimental ma?

nipulations were extremely and uniformly successful.25

26The question continued: "If 10 means that you believe the out?

For example, 71.4 percent of those told that the family come is completely fair to the families of the victims and 1 means

was allowed to tell its story correctly perceived this ma? the outcome is completely unfair to them, which number from 10

while 74.4 percent of those told the family to 1 best describes how you feel? For example, you might answer

nipulation,

with a 4 if you think the outcome is only somewhat unfair, or a 7

was denied the chance to tell its story accurately an- if you think the outcome is somewhat fair to the families of the

swered the manipulation check. Perhaps because the victims."

truth and reconciliation has been so salient

in In the pretest we also measured perceptions of how fair the

process

outcome was from the respondent's own perspective rather than

South Africa, these vignettes seem to have caught the at?

from the families* perspectives. Since responses to this question

tention of our respondents. were very strongly correlated with responses to the family fairness

question, we concluded that when people view an outcome as fair

to the family they are also asserting that they believe the outcome

25One should not assume that manipulations routinely pass their is fair from their own viewpoint. (See also the evidence presented

"checks" since in fact many do not?see for example Gibson 1997. above.)

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 549

Table 2 The Effect of Justice Manipulations on Judgments of Fairness to the Victims

aThepercentages are based on dichotomizingthe continuousvariableand placing "uncertain" or "don'tknow"responses in between "unfair"

and "fair."

The percentages in the table do not total to 100 % since some small proportionof the respondents was unable arriveat a view of whether the fami?

lies of the victims were fairlytreated in the vignette.

bDifferenceof Means test: p = .000; ti = .10.

cDifference of Means test: p = .ns; ti = .01.

dDifferenceof Means test: p = .000; r| = .09.

eDifference of Means test: p = .000; x\ = .30.

all four types of justice?is judged to have produced the 22.9 percent assessing it as somewhat unfair.28 Though

fairest outcome = 5.2), while the last vignette?in the combination of the four types of justice significantly

(y

which the family got no justice?is perceived as the least influences fairness judgment, when the families are por-

fair (y = 2.2). This is a quite encouraging finding. Gener? trayed as receiving all four types of justice, 45.7 percent

ally, the mean fairness scores vary considerably?using a judge the outcome fair, while 52.7 percent believe it still

dichotomous measure of the ten-point dependent vari? unfair to at least some degree. Thus, in the analysis that

able (less than or equal to 5 versus greater than 5), the follows, the bulk of the variability being considered con?

percentages judging the outcome to be fair range from cerns how unfair the outcome is judged. This finding of

6.7 percent (version 16) to 45.7 percent (version 1). From course confirms the original intuition undergirding this

the point-of-view of the politics of amnesty, this is sub- project?that amnesty, even under the best of circum-

stantial variation indeed. stances, is not thought fair by most South Africans.

Generally speaking, the outcome in this vignette

(Phillip's amnesty) was not judged to be very fair to the The Effect of the Experimental Manipulations

families of the victims.27 Across all vignette versions, only

24.3 percent of the respondents found the outcome fair, Table 2 reports the effectof each of the experimental

and only a minority of these considered the outcome to be manipulations on judgments of fairness to the families.

quite fair (8.7 percent of all respondents). Indeed, fully I report several statistics?the percentage viewing the

51.2 percent of the South Africans judged the outcome outcome as to any degree unfair, the comparable per?

quite unfair to the families of the victims, with another centage for those who judge the families to have been

fairly treated29, and the mean and standard deviation of

the continuous fairness judgment.

27Not unexpectedly, these judgments of fairness to the families of

the victim are not strongly related to general assessments of the 28I created a four-category variable from the continuous fairness

fairness of amnesty. The strongest correlation is with perceptions

of the fairness of amnesty to ordinary people, but that correlation judgments, as follows: 1-2: very unfair; 3-5: unfair; 6-8: fair; and

9-10: very fair.

is only .23. This suggests that context does indeed matter, since the

conclusions people draw when they have some details about am? 29This is based on dichotomizing the continuous variable and

nesty are only modestly related to their attitudes toward amnesty placing "uncertain" or "don't know" responses between "unfair"

in general. And of course in the vignettes, the details heard varied and "fair."The percentages in the table do not total to 100 percent

across respondents according to the version of the vignette to since some small proportion of the respondents was unable to

which the respondent was assigned. judge whether the families of the victims were fairly treated.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

550 JAMES L. GIBSON

Perhaps not surprisingly, the single strongest predic? ernment provided compensation. There is clearly more to

tor of perceived fairness is the distributive justice ma? fairness in South Africa than monetary restitution.

nipulation (see the eta coefficients in the footnotes to the Why is not the influence of distributive justice

table). The mean scores on the fairness index differ sub- stronger? This finding may have something to do with

stantially (and of course statistically significantly as well). the unresolved nature of the compensation issue at the

When the government provided compensation, over time of the survey. Perhaps if people thought that com?

one-third of the respondents thought the families were pensation would be more substantial and more likely,

fairly treated, as compared to only 13.9 percent when then the effect of this manipulation would be larger in

compensation was denied. This is a substantial statistical terms of convincing people that amnesty is fair to the

and substantive effect. families of the victims.

Two other manipulations proved to influence fairness The influence of procedural justice also warrants

assessments as well. When the families were given the op- emphasis. The simple act of giving people the opportu-

portunity to "tell their stories" (voice) they were judged to nity to describe their plight publicly is more than one-

have received significantly more fairness than when they third as influential on fairness judgments as monetary

were denied the opportunity to speak. The restorative jus? compensation. Procedural justice is less influential than

tice manipulation also influenced fairness judgments? distributive justice, but it is nonetheless important to re-

when the family accepts the apology, the outcome is member that simple and relatively inexpensive processes

judged to be more fair than when no legitimate apology is can often contribute significantly to perceptions of fair?

forthcoming, with a statistically significant difference of ness. Similarly, a sincere apology from the perpetrator

8.3 percentage points in (dichotomized) justice judg? has an important influence on perceptions that the fami?

ments and a highly significant difference in the continu- lies of the victims are treated fairly. Indeed, the effects of

ous measures of perceived fairness.30 procedural and restorative justice together are roughly

Finally, the retributive justice manipulation had no two-thirds the size of the effect of distributive justice.

influence?24.1 percent of those hearing that Phillip Clearly, compensation is not the only palliative for the

was punished thought the outcome fair, compared to injustice of amnesty.

24.6 percent of those who heard that Phillip was not

punished. Perhaps because so many viewed Phillip as Multivariate Analysis

profiting from the amnesty process, whatever incidental

punishment he may have received is inconsequential to It remains to consider how the conclusions are affected

most.31 by the inclusion of the perceptual variables in the equa?

tion predicting fairness assessments. Table 3 reports the

results of two OLS analyses of fairness perceptions.

Summary

Model I considers only the four dichotomous manipula?

Both the positive and negative findings from the experi- tions as predictors; Model II adds the four perceptions of

ment are substantively important. That the distributive the manipulations (the manipulation check variables) to

justice manipulation is the most influential variable is sig? the equation. The results from Model I are identical to

nificant in light of the continuing controversy in South those discussed above, so no further comment is war-

Africa over the reparations issue. But it is also noteworthy ranted. Model II provides the data of most interest.32

that the influence of compensation is not enormous, and The first thing to note from the analysis reported in

even when compensation is posited, most South Africans Table 3 is that the direct effects of the experimental ma?

view the treatment received by the families ofthe victims as nipulations are strongly mediated by the perceptual vari?

unfair. Indeed, only slightly more than one-third of the ables, as they should be. For instance, the coefficients for

respondents thought the outcome fair even when the gov- the procedural and restorative justice manipulations

achieve statistical significance in the first equation but

30This finding is all the more significant since the research litera? not in the second. Only the distributive justice manipula?

ture would not expect apologies (even sincere ones) to be very ef- tion has a direct effect in the multivariate equation. This

fective under the conditions of the truth and reconciliation pro?

means that even controlling for perceptions of whether

cess: The apology is for a serious offense (a gross human rights

violation), there is little doubt about the culpability of the perpe-

trator, and no formal punishment is given to the amnesty appli-

cant. 32Since the four manipulation variables are, by design, orthogonal,

the bivariate and multivariate results for the experimental vari?

31None ofthe interactions among the manipulations achieves sta? ables do not differ. The perceptual variables are not orthogonal;

tistical significance, and therefore the influence of the variables is instead they are weakly to moderately intercorrelated (average cor-

adequately captured by their linear effects. relation = .18).

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 551

Table 3 The Effect of the Experimental Manipulations and Perceptions of the Manipulations

on Fairness Judgments

Intercept 2.19 .10 .41 .13

R2 .11*** p-j***

Standard Deviation-Dependent 2.90 2.90

Variable

Standard Errorof Estimate 2.74 2.58

N = 3710 *"p<.000.

the families would Three of the perceptual variables?procedural, re?

get some form of compensation,

storative, and distributive justice?have roughly equal

something about the compensation story had a net influ?

ence on perceived fairness.33 To the extent that each of influence in shaping fairness judgments (see both the

the other manipulations standardized and unstandardizedregression coefficients

influences the dependent vari?

in Table 3). The statistical advantage that objective dis?

able, its effect is mediated through perceptions.

The explanation of this first finding may well lie in tributive justice has is reduced to parity when the per?

meaning the respondents attach to the ceptual variables are considered. Those who perceive a

supplementary

compensation manipulation. In addition to providing legitimate apology are almost as likely to judge the out?

information about the families of come fair as those who perceive that the families were

compensation given

the victims that was quite accurately per? compensated. The cumulative effect of these three forms

(information

additional certification of the legitimacy of the of justice is fairly substantial: The mean fairness rating

ceived),

families' claim may have been implicitly provided by the for the 418 South Africans who strongly perceive no jus?

fact that the government gave the families compensation. tice on all three of the relevant justice variables is 1.8

And indeed, those who were told the family received (with 97.4 percent judging the outcome as unfair), while

the mean for the 170 respondents asserting strongly that

compensation were, according to the data, more likely to

assert that the families received restorative and procedural the families received all three forms of justice is 6.1

as well (with 40.2 percent

judging the outcome as unfair and

justice (but not retributive justice?data not

But even 59.8 percent perceiving it as fair). This is substantial

shown). beyond these specific forms of justice,

variation indeed.

something else about getting payment for one's pain en-

hances perceptions of the fairness of the outcome of the The lack of a dominant influence of distributive jus?

tice is a crucial finding. Whether the families are per?

amnesty hearing.34

ceived to have gotten compensation is influential, but is

33This finding is particularly surprising in that this manipulation is littlemore important than whether the families were

the most accurately perceived of the four (as shown by the r| coef- given voice through the truth and reconciliation process,

ficients reported in Table 1) and therefore its effect should be fun- and whether the families received a credible apology.

neled through perceptions.

South Africans are not much influenced by retribution

34Perhaps the manipulation check for compensation is contami-

nated by those who perceive some compensation in the experi?

ment but judge it inadequate, and therefore answer that compen? sometimes capture both perceptions and judgments of reality. This

sation was not received. It is possible that manipulation checks possibility cannot be explored with the data at hand.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

$$2 IAMES L. GIBSON

(at least as represented in the vignette), but they think those of Asian origin being more likely to judge the out?

about fairness in the truth and reconciliation process in come fair to the families of the victims (b = 1.06, s.e. =

terms of far more than simple compensation. .50). Second, there is a slight tendency for those of Asian

origin to be less influenced by their perceptions of the

(b = -.27, s.e. = .13), and perhaps by their per?

Racial Differences in Judgments of apology

= -.24, s.e. = .13), with

Fairness to the Families of the Victims ceptions of procedural justice (b

each of these perceptions having little effect on the fair?

The analysis to this point pertains to all South Africans. ness judgments of Asians but some effect on the judg?

But race continues to divide the country, perhaps par- ments of Africans.36 None of the other differences

ticularly on matters of truth and reconciliation, so it is achieves statistical

significance?overall, Asian South Af?

therefore necessary to consider whether these results ricans and black South Africans reacted to our experi-

characterize all four racial groups in the country. ment fairly similarly.

I began this analysis with a saturated interactive The largest and most significant racial differences are

model. That is, I supplemented Model II with (a) a set of between blacks and whites. Each ofthe sets of race-based

three dummy variables representing whites, Coloured interactive variables contributes to a significant increase

people, and South Africans of Asian origin, (b) a set of in explained variance. Whites tend in general to view the

interactions between the race dummy variables and the outcome as more fair (b - 1.16, s.e. = .29), to be less in?

formal manipulations in the experiment, and c) a set of fluenced by their perceptions of compensation (b = -.25,

interactions between the race variables and the indicators s.e. = .08), to be less affected by the apology manipula?

of perceptions of the experiment. The addition of each of tion (b = -.52, s.e. = .24), and perhaps to be more af?

the sets of variables to the basic equation was highly sta? fected by their judgments of how severely Phillip was

the hypothesis that at his (b = .15, s.e. = .08). This last find?

tistically significant, confirming punished by family

least some differences exist in how the experiment af- ing, though only marginally significant, is the only in-

fected various racial groups. Consequently, a more re- stance in which punishment has any influence on fair?

fined analysis of racial differences is required. ness judgments. None ofthe other interactive coefficients

The central question here is whether other racial achieves statisticalsignificance.

groups in South Africa differ from the African majority. In general, racial differences in reactions to amnesty

Therefore, I conducted three regression analyses, in each in South Africa are not as pronounced as such differences

instance comparing a group with the views of blacks. are in many other areas of political life. While two of the

These results are reported in Table 4. For instance, the three dummy variable coefficients achieve statistical sig?

first equation compares whites with blacks, with the null nificance (whites and South Africans of Asian origin),

hypotheses for the dummy and interactive variables pre- only 3 of 24 interactive coefficients are significant at .05,

dicting no racial differences in the coefficients. Because I with only 2 additional coefficients significant at .05 < p <

am interested in testing for racial interactions with the .10. Black South Africans are somewhat more likely than

experimental and perceptual variables?and because the other South Africans to judge the fairness of amnesty in

primary finding is that few interactions exist?the most terms other than strictly distributive outcomes. None?

useful information to report in Table 4 is the results of theless, it is worth reiterating that the dominant view in

the various significance tests.35 all racial communities is that the outcome of the vi?

The findings for the black versus Coloured regres? gnette?Phillip getting amnesty?was unfair.

sion are unequivocal?neither the dummy variable nor This last point requires an important qualification.

the interactions achieve statistical significance. When As I noted above, the vignette referred to a scenario in

it comes to judgments of fairness, black and Coloured which a representative of a group the respondent dislikes

South Africans differ little. a great deal was given amnesty. Presumably, not many

South Africans of Asian origin do indeed differ from South Africans object to amnesty being given to groups

Africans in a few respects. First, the intercept varies sig? with whom they are affiliated or of whom they approve.

nificantly (represented by the dummy variable), with Amnesty is controversial in South Africa because the

people who are going free are those who did dastardly

35Forinstance, the entry of .029 in the first column for the restor? this is true for blacks,

things to one's compatriots?and

ative justice-race interaction indicates that there is a statistically

significant difference in how whites reacted to the restorative jus?

tice manipulation as compared to the reactions of black South Af? 36Indeed, South Africans of Asian origin are the only group for

ricans. Most coefficients achieving statistical significance are dis- whom the addition of the perceptual variables to the experimental

cussed in the text, where the actual regression coefficients (and equation (i.e., Model II) does not result in a statistically significant

their standard errors) are reported. increase in explained variance.

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDGING THE FAIRNESS OF AMNESTY 553

Table 4 Racial Differences in Reactions to the Amnesty Experiment

Equation Comparing Blacks With

Independent Variables

Manipulations

Procedural Justice

Retributive Justice

Restorative Justice

Distributive Justice

Perceptions of Manipulations

Procedural Justice

Retributive Justice

Restorative Justice

Distributive Justice

Race Dummy Variable .000 n.s. .033

Race-Manipulation Interactions

Procedural Justice

Retributive Justice

Restorative Justice

Distributive Justice

Race-Perceptions Interactions

Procedural Justice

Retributive Justice

Restorative Justice

Distributive Justice

Equation Statistics

Intercept (s.e.)

R2

Standard Deviation-Dependent Variable

Standard Errorof Estimate

N

Note: This table reports the results of three independent regressions, in each instance comparing the black respondents withthose of the other race.

Cell entries are the significance of the test of the nullhypothesis that the regression coefficient is indistinguishablefromzero. H0:b = 0. The indepen?

dent variables representingthe race interactionstest for the bi-racialdifferences in the effects of the manipulationsand the perceptions of the manipu?

lations.

n.s. = not statisticallysignificant at p < .10.

All probabilitiesless than .10 are shown. When coefficients are statisticallysignificant, the actual coefficients are reported in the text of this article.

for whites, for Coloured people, and for those of Asian judgments; and (3) the possibility that the democratic

origin. Because everyone feels aggrieved by the unfair- experiment will be consolidated in South Africa.

ness of amnesty37, racial differences in fairness assess- Most South Africans oppose granting amnesty to

ments are not large. those who committed gross human rights violations dur?

ing the struggle over apartheid. However necessary am?

nesty may have been to the transitional process, the fail-

ure to achieve any sort of retributive justice is deeply

Discussion unpopular. Even when all four forms of justice investi-

gated here are present, only half of the South African

This analysis supports conclusions about three impor? population approves of amnesty. The other half seems

tant topics: (1) assessments of amnesty by ordinary unable to reconcile with granting amnesty to those com?

South Africans; (2) the political psychology of justice mitting gross human rights violations during the

struggle over apartheid.

37It is worth reiterating that racial differences in how fair amnesty But justice does matter. Whether people are willing to

is thought to be to people in general are trivial (see above). tolerate amnesty depends in part on whether other forms

This content downloaded from 130.225.157.199 on Mon, 3 Feb 2014 17:12:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

554 JAMES L. GIBSON

of justice are present.

That judgments of the fairness of In terms of theories of justice, this article demon?

amnesty change by nearly 40 percentage points?from strates the utility of moving beyond the conventional

the condition under which no justice is received to that emphasis on distributive and/or procedural justice. Jus?

in which all four types of justice are received?is highly tice is a multi-faceted concept, and research ought to be

significant for the politics of amnesty. To some impor? sensitive to the importance of different aspects of justice.

tant degree, alternative forms of justice can make up for And of course one can only ascertain which type of jus?

the inherent unfairness of amnesty, at least for a sizable tice is relevant to a particular dispute if all types are si-

portion of the South African population. multaneously measured and tested in the analysis. Future

And justice is about more than compensation. Of research should also make an effort to test theories of

course reparations matter, and in the objective portions justice more directly against material theories.

of this experiment (the formal manipulations), compen? Though I have made some progress here, we cer-

sation to the families of the victims has the strongest in? tainly need to understand more about the role of public

fluence on perceptions of fairness in the granting of am? apologies in political controversies. In my research, I pur-

nesty. But other, far less costly types of justice are posefully neutralized the issue of the sincerity of the

influential as well. Sincere apologies matter, as does the apology, but of course suspicions of insincerity dog most

opportunity for victims to tell their stories. Those con- apologies in real political controversies. One value of ex-

templating truth and reconciliation processes elsewhere perimental vignettes is their ability to incorporate con-

should take note of the importance of these two non- textual factors into the analysis. Understanding how con-

monetary factors in generating popular acceptance of text shapes the influence of apologies is an important

amnesty. area for future inquiry

In this sense, strict economic instrumentalism is not These findings have clear implications for the cur?

the only motivating factor in judging amnesty. We are rent South African government. First, the original as?

slowly beginning to understand that even rational actors sumption of the truth and reconciliation legislation was

attempt to maximize many types of benefits, including that the inherent unfairness of amnesty could be as-

symbolic, nonmaterial benefits (see Chong and Marshall suaged through compensation. That assumption has em?

1999). That people's political judgments are influenced pirical validity. If the Mbeki government wants to influ?

by more than how much the victims get?that it is cru- ence South Africans to judge the amnesty process as

cial whether what they get is considered fair?cannot any acceptable, it ought to provide adequate compensation to

longer be questioned. Theories of political behavior must those who established themselves as victims of gross hu?

pay far more attention to the role of justice consider- man rights violations during the apartheid era. Indeed, at

ations in politics. this stage in the process, few mechanisms are available to

I have made little progress here toward understand- the government to enhance the perceived fairness of am?

ing the dynamics of when different forms of justice expec? nesty, so perhaps the only option available to the govern?

tations will become salient and dominant. My analysis is ment to affect perceptions is to properly compensate the

able to order different aspects of justice according to their victims.

salience within the South African context, and the empiri- At one level the TRC seems to have been fairly suc-

cal results generally satisfy those expectations. Unfortu- cessful in South Africa, and certainly the procedures the

nately, we have little understanding about how various as? TRC employed are procedures that influence judgments

pects of justice get mobilized, adjudicated, and applied in of fairness. It seems unlikely that more formal processes

general. In this experiment (as in most experiments), the of dealing with those admitting gross human rights

vignettes were structured so that the four types of justice abuses (e.g., trials) would be as successful at giving voice

were orthogonal to each other. Such is surely not often the to the victims and their families and at making apologies

case in actual disputes over justice. Indeed, real controver- meaningful. Truth and reconciliation hearings seem to be

sies perhaps make inseparable some ofthe dimensions of an instance in which informal justice has some signifi?