Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scan 4

Uploaded by

Bernard Vincent Guitan Minero0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views45 pages....

Original Title

Scan4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document....

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views45 pagesScan 4

Uploaded by

Bernard Vincent Guitan Minero....

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 45

PLO Ae Fie ealilay)

2019.08.14 11:53

SE vats NEVER MET, fellow teacher, but your act

of opening these pages is introduction enough. It tells

me something important about you. Either you will

soon launch your career in the classroom and would

like some tips on what to expect; or you have already

started to teach and would welcome some tips on how

to hone your skills. My title has obviously stirred your

curiosity. All good teachers and would-be teachers are

eager for tips on the what and the how of teaching.

Before getting down to these, however, let us

examine a more fundamental question—the why of

teaching.

Why be a teacher? Why spend your days in the

humdrum routine of a school (and believe me, at times

it is excruciatingl ini

‘oneal eas 2 to hordes

women the mysteries of math : ee aie

lematics or geography

Oho) sa alae

ae

LetTTER TO A YOUNG TEACHER

or literature? The answer you give will determine, more

than anything else, your success or failure in the class-

room. If you answer wrongly, no amount of advice

from me or anyone else will be of much help.

Why teach? Many answers are possible, but one

spells death to a career in the classroom. If your over-

riding motive is money, go elsewhere. The world has

many respectable ways of making a living, and most

of them hold out hope of a far fatter paycheck than

you will ever pocket as a teacher. In many parts of

the world, in fact, teaching is a relatively low-paying

profession, dooming its practitioners to lives of gen-

teel poverty. So if money is your motive, try trading

or farming or even hair-styling. But don't inflict your-

self on innocent students. They deserve better.

Then why teach? At least part of the reason [hope

is on your lips will possibly strike you as banal. It is

that for reasons you yourself may not fully compre-

hend, teaching appeals to you. You feel somehow at-

tracted to it. Like all good teachers, you have a touch

of the actor, perhaps even the ham actor, in you. You

like to perform. You also have a touch of thi

or nurse in you. You like to help other people, espe-

cially young people. You enjoy the prospect of pre-

oung and by

e doctor

siding over a captive audience of the y

the magic of your words opening their still half-formed

Why Teach?

minds to new and exciting realms of knowledge.

I suspect you always liked school. More perhaps

than you have yet admitted even to yourself, you en-

joyed your own days as a student. It was then that

you discovered how much pleasure is to be found in

exploring the world of learning. You are now con-

vinced that a career leading others to explore this same

world is not only in itself more important but more

personally satisfying than a career immersed in the

everyday world of business. Introducing the young to

such subjects as the history of your nation or the work-

ings of the human body or the pleasures of poetry

strikes you as infinitely more gratifying than hawking

products like cornflakes or cosmetics. In short, among

your motives for choosing a teaching career, this one

stands out: you expect teaching to be fun.

Fun is nota very lofty motive, you may think, and

probably not one you expected me to stress. True

enough, but | am convinced that without this to start

with, even the loftiest motive cannot guarantee suc-

cess in the classroom. Don't even think of making

teaching your career unless you expect to find it an

enjoyable and fulfilling career. As someone who has

spent half a lifetime as a teacher, | cam assure you

that teaching certainly is fun, often a barrel of fun.

It always was for me,

2 Bo) e ise

mar

a

LETTER TO a YOwNe Teacher

Look back over your years as a student. Tick off

the teachers who impressed you most, who kept their

classes alive from the opening to the closing bell and

from whom you learned the most. Didn't the vigor in

their voices and the sparkle in their eyes prove they

took pleasure in what they were doing? And didn't

their colleagues who were duds in the classroom let

you know in a thousand subtle ways how tiresome

and unrewarding they found their occupation?

That you expect your life as a teacher to be re-

warding does not mean, however, that you should

expect never to feel tremors of misgiving during the

moments before you enter the classroom. All teach-

ers, veterans as well as novices, know how daunting

it sometimes is to look out ona sea of faces and start

expounding on their subject. Such nervous flutterings

are natural, even desirable. They prove you are en-

thusiastic about your subject and anxious not to fail

in sharing your enthusiasm with your students. Ac

tors and orators—the first rate ones at least—all know

what they feel like. heres

You should also expect that teaching will often be

a wearying task. First of all, it will demand the grind

of daily preparation for class. Worse still, it will entail

seemingly endless days of tedium as you correct €x-

amination papers. Finally, you must be prepared for

Why Teach?

inevitable misunderstandings with students and clashes

with school authorities. Weathering such storms is part

of the teaching profession.

For dedicated teachers, however, their job is never

just a chore. They are so filled with the conviction

that they are performing a valuable service for the

younger generation that they don’t bother counting

its costs. And above all, they never cease finding that

despite all its inconveniences and setbacks, teaching

is still fun.

2019.08.14 11:54

LETTER TO A YoOUnS TEACHER

but he sounds as though he’s reading facts from

an almanac. Geography used to be my favor-

ite subject, but he’s managed to make me hate

itas much as math.”

“Miss Santos was a real pill today, Sat at

her desk and droned on and on about the

battles in some ancient war. Didn't say a thing

that our textbook doesn't say better. We all

fell asleep.”

Students do not judge their teachers by the aca-

demic honors they have won, the learned volumes they

have published, or the number and level of their higher

degrees. Their favorite teachers are of course in total

command of their subjects, but even that is not the

main reason students praise them. It is rather that they

have the knack of making the seemingly dreariest

subject interesting. Students are no different from the

rest of mankind. They dread being bored.

This, then, is the main challenge you face as a

teacher. How can you keep your pupils alert, alive,

watching you and listening to you during every mo-

ment of your instruction?

First of all, keep in mind the old Latin saying, Nemo

dat quod non babel, meaning you can't give to others what

you don't have yourself, Interest passes from person

to person the way electricity passes through a wire.

14-

—=

Staying Alive in the Classroom

Don't expect to hold your students’ attention unless

you are plugged into the current yourself, They will

be interested only if you are.

That means you must never stop studying, never

feel you know all you need to know about your sub-

ject and can coast along on habitual knowledge. Just

knowing what your syllabus requires you to cover is

not enough. Like any motor in active service, you need

a constant supply of new fuel.

Why do some teachers dry up after a year or so in

the classroom? Why are their classes as dead as the

proverbial doornail? Because their own interest in their

subject has expired. They have lost their appetite for

| it and no longer believe in its value. They have stopped

: reading about it, talking about it, caring about it. Once

their students sense that a teacher is scraping the

bottom, is no longer growing in curiosity and knowl-

edge about the subject of instruction, their attention

level sinks too. Stale bread is uninteresting bread.

Do you teach Spanish> Don't just rely on your text-

book, the notes you took in college or graduate school,

and the plans you drew up during your first year of

‘caching, Read deeply in the literature of Spain and

MS former colonies. Keep your eye open for tours to

Spanish-speaking lands. If possible visit their

sies and see what kind of support they can

OLY

LeTTER TO A YOUNG TEACHER

teacher of Spanish. (You may be surprised at the warm

welcome you will receive.) Make Spanish and every-

thing connected with it a lifetime hobby.

Do you teach history? Read biographies of the

famous men and women who lived in the period you

are covering. Science? Learn as much as you can about

the beginnings and development of your science and

the lives of those who contributed to its advance.

Geography? Devour travel literature and accounts of

great explorers.

No matter what subject you are teaching, you will

find more than enough material in the library and

elsewhere to keep your interest alive.

Vacation time can be precious. It may give you a

chance to take additional courses, attend seminars,

visit museums and other exhibitions. Even movies and

television programs can be of help. Your own curios-

ity will suggest further ways to expand and strengthen

your grip on your subject

Don't be surprised or disappointed if what you

learn from these activities does not gain a single direct

ee [abe That i not their purpose.

you earning and curious to learn more,

they are worth every moment you spend on them.

Whe i

~ 2 your own enjoyment of your subject and

T Curiosity about it die, the teacher in you also

=

_"——e™ a

Staying Alive in the Classroom

dies. You will start hating your subject, hating your

job, and possibly hating your students too. You will

be just another burnt-out teacher.

If you feel these symptoms coming on and find it

impossible to rekindle your old enthusiasm, you have

one last resort. Go to the authorities and implore a

change in the subject you are teaching. | have seen

such fresh starts accomplish wonders for teachers

who were suffering from burn-out.

2019:08)14 11:54

2019.08.14 11:54

fe ees

YounG TEACHER

formal education. It also includes the continued study

and interest you devote to the particular subject you

are teaching. This we have already looked at.

Now let us suppose you have completed this

remote preparation with honors. Tomorrow you will

meet face-to-face with a room full of live students.

What more must you do? What kind of immediate

preparation is necessary?

As much as possible, on the day before you meet

a class, you should go over the material to be taught,

How long this will take and whether you should trust

memory or bring some jotted notes with you to the

classroom will vary. But the rule is clear. Never walk into

the classroom cold. You must know in advance exactly

where you are going, what material you intend to

cover. Meticulous planning is necessary. Don't think

you can fake it. Remember your own days as a stu-

dent. Your students will be no slower than you were

in spotting the shabbily prepared teacher. In this

matter, students are rarely fooled.

Next comes the hard part, where even the most

promising teachers are in danger of missing the mark.

They think no further preparation is needed. Do you?

Say you are a history teacher and have an exact

knowledge of the battles you are going to discuss, a

literature teacher and have worked out a careful ana-

Always Prepare

lysis of the poems you intend to discuss, a science

teacher and know all there is to know about the law

of physics you are going to explain. Is that enough?

Are you now ready to enter the classroom, call the

students to order, and commence teaching?

You would be if your students were pure intellects.

Then your task would be simply to give a clear pre-

sentation of the ideas and information that are stored

in your own brain, confident that these will automa-

tically enter the brains of your students. If they do

not, then your students will have no one to blame but

themselves. They must have been sleeping or day-

dreaming or watching the shenanigans of the class

clown who sits in front of them. Can anyone hold

you responsible for your students’ lack of attention?

Yes. | can and do. | say your preparation has been

incomplete. You have prepared intellectually, yes. But

teaching is not a purely intellectual enterprise, any

more than students are purely intellectual creatures.

Aristotle defined man as a pasos animal,” a defini-

tion that is a in the 1

LETTER TO 4 Younc TEACHER

nalit The pr

TH

challenge you face when you walk into the inh ee:

's not intellectual but Psychological =

he ps)

attention, Ne os

We can distinguish tw

(0 kinds of attention,

neous and willful. The fj N: sponta.

rst is effortless, We give it to

ly interesting mogt women

the subject you teach falls in a similar category!

Do not count on such luck, however. Only the

rarest of students finds anything inherently interest-

ing in quadratic equations or English punctuation or

the geography of Iceland. Yet subjects like te make

up a large part of what is taught in school. Don't me

the mistake of thinking that because you find a sub-

i ill feel the same way.

ject interesting your students will Ze pe

More often than not it is the teacher's job to a

their as yet dormant interest.

2019.08.14 11:55

LetTeR TO A YOUNG TEACHER

on them, our minds riveted on what they said, They

cast a spell.

How did they do it? What was their secret>

Actually, it was no secret at all. Some of them were

naturals. They knew the art of compelling attention

intuitively, but any teacher can master their techniques

the hard way, The much maligned tribe of psycho-

logists has helped us by analyzing the phenomenon

of human attention. Poke around in your library and

you can find their conclusions in almost any elemen-

tary psychology textbook. | have often been astounded

at how few are the teachers who take the trouble to

consult such books

The first thing a teacher can learn from these psy-

chologists is that it is not usually the subject matter

one is teaching that captures the students’ attention,

but the way the subject matter is presented. They point

to what they call attention factors. However uninterest-

ing the day's lesson may be in itself, however distracted

the students are, the teacher can package the lesson

in such a way that one or more of these factors is

brought into play. Call them the sugar coating on the

pill of learning, the bait that hooks the unsuspecting

student. Used with skill, they have the power to make

the most unappetizing material tasty and the drab-

best lessons exciting.

AST NO ae MESS

On

2019.08.14 11:

Letter TO aA YOUNG TEACHER

the classroom, pacing the aisles and addressing their

pupils now from the front, now from one of the sides,

now from the rear. Some (this was one of my favor-

ites) like occasionally to sit on the desk as they con-

duct their class. Some use gestures frequently, point-

ing to the writing on the blackboard or to other

objects connected with the lesson. Choose whatever

method suits you, or better still, a mixture of all,

The younger the teacher, the easier and more

natural to keep in motion. But the older ones make a

mistake if they forsake physical activity in the class-

room altogether. Whatever your age, it is unwise to

spend every moment of every period sitting behind

your desk as still as a marble Buddha. Let your pupils

see you are alive.

Make your lesson move too. In your anxiety to

drive some point home, you may be tempted to stay

on it too long. Move on, especially if you notice the

class growing restless. You can always return to that

part of the lesson on another day.

Above all, bring your students into the act. The

easiest way to do this is by frequently interrupting

yourself to ask questions. Devising good questions

and asking them properly are skills that all teachers

must acquire. Without them, almost all teaching would

be by the so-called “lecture method,” a discredited

2g

= “Sree é

PCE I Oo it y

method of teaching that hardly works even on the

upper levels of schooling, where it is usually found, and

not at all on primary or secondary levels. Once we

eliminate the give-and-take of question-and-answer

between teacher and students, the whole point of

building schools and hiring teachers is lost. Listening

toa lecture is little different from reading a chapter in

a textbook. Who needs a classroom ora teacher for that?

The Greek philosopher Socrates was by universal

acclaim one of the greatest teachers who ever lived.

To him we owe the method of teach

ing that still goes

by his name,

the “Socratic method,” which relies

almost entirely on questions. He was fond of profess-

'ng Ignorance of a subject and then

questions to the person who had sou,

from him. Gradually, like a clever ¢

putting a series of

ght enlightenment

TOss-examiner in a

Letter to a Younae Ttacuer

Even if your method is not

asking questions should take up m

the classroom. Their usual purpo:

grade students on the accuracy

to keep them awake and on thei

the students know this is their

can easily do by your manner. 1

mentally grading their answers,

and clam up.

exactly Socratic,

uch of your time in

se should not be to

of their answers, but

T toes. Itis best to let

Purpose, which you

f they think you are

they may grow tense

What should you question them on? The material

you told them to prepare the night before, of course

But even when you have assigned nothing for them

to prepare, questions are a good way of holding their

attention, You can often interrupt what you are say-

ing with questions like “Why do you think that is sor”

or “Can you suggest any examples?" or “Does anyone

have a better idea?" or “Do you agree? Why?" Occa-

sionally you might try an elliptical (fill-in-the-blank)

question, in which the pupil supplies the missing word.

Asa ule, address your question to the whole class,

pause briefly to let it sink in, then single out oe a

dent for the answer. That gets all of them thinking an

adds to the suspense. Move from student to a

for the answers, picking especially those a

signs of nodding. Do not stay on any student

i i ng.

long, however. It may give the impression of naggi

30°

Activity

One other point. Your method of questioning

should always be Platonic in the sense that, like him,

your manner should be gentle, never sharp and impe-

rious. Martinets may make good marine instructors

but not good teachers of the young. In my experi-

ence, the most successful teachers had a classroom

manner that was relaxed and conversational.

You have probably attended public lectures at

which the speaker closed his remarks by inviting

questions from the floor. Remember how the audi-

ence instantly perked up and the atmosphere grew

| livelier? As a teacher you will have the same effect if

you welcome questions from students. It is better not

to set aside a special time for such questions. Let your

students pop them throughout the class period. Some

of the best teachers | had

hands fora question when

In this way we were

Occasionally,

encouraged us to raise our

ever curiosity prompted us,

constantly being perked up.

of course, you will have material you

At eeraeh 2019.08.14 11:55

r SHOT ON MI A2

Ml PLU NUR alceay

Vv

bbe tee,

Vm CHILDREN GO to school they leave behind

the cozy comforts of their homes as well as the free-

dom of the fresh outdoors. These make up their real

world, the unfettered and ever changing world of

friendly sights and sounds. Once the doors of the

classroom close behind them, they find themselves

cooped up in a gray world of inflexible rules and

irksome tasks. To elicit and hold their attention the

wise teacher strives to inject into the classroom

reminders of the many-colored world outside.

In this regard, teachers of the physical sciences

have an advantage. If their school has adequate equip-

ment they can give tangible demonstrations of the

arid statements in their textbook. | remember how

silent and attentive my thirty or so high school class-

maies and | were when our chemistry teacher brought

an odd-looking piece of equipment to class and

23300

LerterR TO A YOUNG TEACHER

announced that we were about to behold a myster;-

ous process called electrolysis. He proceeded to pour

some tap water into the contrivance, pulled a switch

and presto, gases started gushing through two ripes

Until that moment I think we had only half.

believed what our textbook said about water being

composed of atoms that were one part hydrogen, two

parts oxygen. Now the abstract symbol H,0 repre.

sented unquestionable reality. We had actually wit-

nessed that the water we used to slake our thirst and

wash our hands was in fact a union of two invisible

gases. The world of science was beginning to make

its secrets known

Conversely, | remember how apathetic my col-

lege classmates and | were when our physics teacher

tried to explain the secrets of the atom (this was shortly

after the explosion of the Hiroshima bomb) by filling

the blackboard with a series of incomprehensible for-

mulas. The blackboard can bea great aid to teaching,

and all teachers should learn to use it. But it must be

used wisely—to elucidate, not obfuscate.

Some subjects, like quadratic equations, the quan-

rbs, prob-

tum theory, or the conjugation of irregular ve!

he reality of

ably cannot be linked in any fashion to t

er subjects can.

everyday experience. But many oth ae

History, for example, should not be taught

34

Reg lity

series of dates and dry facts but as a story, for that is

what it is. Like all stories it is about the successes and

failures of human beings who inhabited the same world

we do and had inner feelings no different from our

own. It is not going too far to say that the history

teacher should prepare for the class the way a profes-

sional storyteller prepares for a public recitation Once

the students are aware that history is a true-to-life

drama as gripping as any they read about in the daily

newspapers, they are hooked

I knew a teacher of history who tried to make his

classes on the American Civil War as exciting as a

movie. His vivid descriptions recreated the battles

He even mimicked the dialogue of the officers and

politicians as they plotted and fought their battles

This did not demand extraordinary acting ability on

his part. Actually, he had no such gift. But it did de-

mand some internal rehearsals before he entered the

classroom, as well as a willingness to throw himself

into various parts. Of course, an extremely shy per-

son would not dare do what this teacher did. But

extremely shy people usually have the good sense to

join some profession other than teaching.

One of my colleagues, a teacher of freshman eco-

nomics, made a yearly field trip with his students to

the stock exchange, where they could watch the dis-

NSS:

2019.08.14 11:

LL VL 80'6L0d

Cs

LETTER TOMASTOUNG TEACHER

mal science in action. After observing how the world

of high finance actually works, they had to write a

report, interpreting what they saw. A field trip like

this does not bring the real world into the classroom,

but the classroom into the real world. Of course, not

every subject can be the object of field trips. But

where possible, wise teachers make them Part of their

annual schedule

A teacher should learn to use what visual aids and

other props are available in the school—slide shows,

maps, globes, charts, pictures, diagrams, recordings,

videotapes, and so on. All these add a touch of color-

ful reality to the drab uniformity of the classroom

I once knew a literature teacher whose syllabus

included Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a

poem featuring that preposterous land-and-sea bird,

the albatross. He knew that the odds that any of his

students had ever seen an albatross in the flesh were

close to zero. So when he learned that a nearby mu-

seum had a stuffed one on display, he had them go and

inspect it. Even Coleridge never had that opportunity.

wn

Jesus, the carpenter of Nazareth whose ©

5 minimal, was by

schooling was by modern standard fall

“st teachers ©

common acclaim among the greatest teache a

est. Although not W!

time, if not actually the great

Is tell us more about

ten for this purpose, the gospe

36

SE

Reality

the art of teaching than a thousan

gogy. Teaching the high truths ry

so down-to-earth that the sim

comprehend them is a challen,

of the gospels must face on S

among them realize that to meet this challenge all

they have to do is look at the gospels, see how the

itinerant preacher named Jesus once taught, then go

and do likewise. All teachers today, even of the most

secular subjects, can Profit by doing the same

In the gospels we see Jesus teaching, not in the

rarefied language of theologians, but in the gritty

language of common folk. Centurie

€ra was invented he knew

dear to newspaper people,

thousand words.” His Pictures, of course, were made

with words, but they were picture-

abstractions, They pointed to the

listeners lived in, the fields, hills,

estine. That is the kind of language every teacher

should strive to adopt. Never

try to impress your

students with highfalutin language. Your job is to

make them attend to the meaning of your words, not

their fancy pedigree.

Jesus was famous for making his points with sto-

ries, Some of them, like “The Good Samaritan” and

d textbooks on peda-

f heaven ina manner

plest churchgoer can

ge that every preacher

undays. The wise ones

s before the cam-

the truth of the saying

that “a picture is worth a

words, not windy

Physical world his

and waters of Pal-

37

LetTeER TO A YOUNG TEACHER

"The Prodigal Son,” are among the world’s best. A

teacher cannot tell too many stories. There is no

surer way to hold the attention of students. Like the

stories of Jesus, of course, they should have a point

that connects with the subject being taught, Finding

such stories is one of the challenges that face you

every time you prepare for class.

Where should you look? First, within yourself.

Nothing captures attention better than an anecdote

drawn from a teacher's personal experience. You can

also hunt for anecdotes about the people who became

famous for their work in your subject. | have already

stressed that the teacher must read beyond the bare

minimum contained in their syllabus. Here is one place

where such reading proves its value, Just mentioning

an incident from the lives of people like Karl Marx

or Louis Pasteur or Robert Louis Stevenson adds a

human dimension to your subject

Every time you encourage reality to poke its head

into your classroom, your students will turn up the

volume on their internal attention machines. Make sure

they keep it on high.

JER YOU IMAGINE anything less interesting than

a street map of some town you have no intention of

visiting? Or duller than a set of instructions on how

to build a raft? But think of how closely you would

examine that map if in an emergency you were trying

to locate a doctor's address in that town. And how

attentively you would pore over those instructions if

you found yourself marooned on a desert island. We

have no trouble attending to things we consider

vitally important. We are never bored by caring for

our own needs.

Admittedly, history records some people who gave

scant thought to their own needs. Think of such pearls

of Christian compassion as Damien the leper or

Mother Teresa, who made attending to the needs of

others the main occupation of their lives. These, how-

ever, are the exceptions. William James told the truth

2019.08.14 11:4

39

———_

LETTER TO A YOUNG TEACHER

about the vast mass of humanity when he wrote,

‘The most natively interesting thing to a man is his

own personal self and his fortunes.”

This does not mean we are all evil, only that we

are not all saints. Our primary instinct is self-preser-

vation, taking care of Number One.

This truth is important for teachers. Say you are

teaching hygiene to a class made up of young male

athletes and announce that you are about to explain

how they should go about washing their faces and

brushing their teeth in the morning. Can you realis-

tically expect them to hang onto your every word?

Young male athletes have more vitally important

things to attend to than clean faces and sparkling teeth.

Now tell the same group of young men that you are

about to explain surefire formulas for preventing

muscle fatigue and improving muscle control, and

watch them sit up and listen. Or imagine you are told

to give a group of girls two courses, one on how to

add pounds to their weight, the other on how to stay

slim for the rest of their lives. To which course do you

think they will flock?

Whatever subject you are teaching, the trick is

to find some reason why it is vitally important that

your students master that subject. When and if you

" i ce on

find it, do your best to impress this importan'

40

The Vital

your students. If you succeed in this, their attention

will be automatic.

Note that by ‘vitally important” | do not mean

something that is absolutely necessary to preserve life.

Unless you are teaching pilots how to land a plane or

medical students how to do open-heart surgery, hardly

anything you teach will be that important. To be what

I here mean by vitally important it is enough that a

knowledge of your subject will contribute strongly to

a contented life. In this category most people would

include such things as satisfactory employment, rea-

sonable prosperity, and a capacity to use one's leisure

time in a fruitful, fulfilling way.

Mathematics teachers can emphasize how impor-

tant in many careers are basic mathematical skills (the

pocket calculator has not rendered arithmetic totally

obsolete), foreign language teachers can explain why

in today's global market linguistic versatility can

mean the difference between success and failure in

business, teachers of literature can dwell on the

enduring and higher pleasures to be derived from the

habit of reading the great masters of fiction and

Poetry, If you can find any link between the subject

you teach and the future career and contentment of

your students, don't keep it a secret, Convince them

that the link is genuine.

Al

2019.08.14 111:

aE

LETTER TO A Younc Teacuer

But what if you cannot convince them? Or if, hard

as you search, you find no such link? | do not know if

it is still true, but certainly some of the subjects that

were routinely taught when I was young seemed then

and still seem to me to be utterly unrewarding. Why

in the world were we required to learn something

called dry measure? Who cares that a peck of bird

seed equals eight quarts of bird seed? And except that

it gave pleasure to those students who enjoyed any

mathematical challenge, what profit was there in learn-

ing the mysterious process for deriving square root?

Who gives a hoot for square root? (Since writing these

words | have learned of two groups that definitely do

give a hoot—electrical engineers and statisticians

How much or little this information would have mat-

tered to my classmates and me when we were forced

to learn square root over half a century ago, | leave the

reader to judge.)

If you are assigned to teach a subject you deem as

unprofitable as square root or if, try as you may, you

cannot convince your students that your subject ac-

tually is important, you have one last recourse —Your

students’ fear of the coming examination. In their

quest for a good grade, students are often willing to

give their undivided attention to subjects even duller

than dry measure

42

The Vital

Some people (including me) think too many stu-

dents are overly concerned about doing well in ex-

aminations. They worry themselves into a nervous

frenzy at examination time. But without going to that

extreme, most students are rightly concerned about

getting at least minimally passing grades. The last

thing they want is the reputation of a dunce. They

also dread bringing home a bad report card for their

tuition-concious parents to scrutinize. And almost all

of them are hoping to do well enough to gain admit-

tance into a good secondary school or college. It would

therefore be folly for a teacher to ignore the impor-

tance of grades in motivating students to pay atten-

tion in class.

Take a lesson from the priest Gerard Manley

Hopkins, one of the finest and certainly the most origi-

nal poet in nineteenth century England. He was also,

as poets often are, shy and dreamy, often to the point

of being impractical. For several years he taught Latin

ve seminary in Ireland. Half a century later, an aged

— mwhto hadbeen one of his pupils was tracked

‘or an interview by an American scholar of

Hopkins. When asked what Hopkins was like in the

classroom, the priest barke.

oe si d back: “Terrible teacher!”

!s judgment? The following inci gests

one good reason eae

43

ZA Oy Keo} sa Silas)

—a—_

LetTTeER To aA YOUNG TEACHER

Hopkins was once picked to compose the final

examination for all students of Latin in Irish schools

and seminaries. His own students were aware of this

and naturally hoped it would give them an advantage.

To his delicate conscience this posed a problem. How

could he keep his students from thinking they could

wrest from him some advance knowledge of the final

examination? How make sure he would not let such

knowledge slip out?

To settle his scruple, Hopkins devised a unique

solution. On the first day of the term he announced

that not a word he spoke in class and not a Latin pas-

sage he assigned for translation would find their way

into the final examination. For examination Purposes,

his students were entirely on their own. Let them study

Latin for the beauty of its literature, giving no thought

to what grades they would receive.

Can you think of a surer way to forfeit their atten-

tion? Is ita wonder that his students, no different from

other students since the beginning of time, instantly

put their pens down, closed their books and turned

him off? For the rest of the term, his audience was the

four walls of his classroom.

So be realistic. Grades do count. Success in oe

aminations is vitally important to students. There is

, ten-

nothing wrong with using this fact to arouse at

44

And there is nothing illegal

over Eiple questions from previous

ations. These and similar strategies are old

as the hills, but also surefire attention-getters. Don't

neglect them. They work.

ey THINGS WILL HOLD the attention of an au-

dience as well as a judicious use of humor...It serves ee

a relaxation from tension and thus prevents fatigue.

(Alan H. Monroe, Principles and Types of Speech. [New

York: Scott, Foresman, 1935] p. 87). Thus opens one

of the chapters in an excellent textbook on public

speaking that was in wide use when I was young. The

author had mainly in mind the kind of humor we ex-

pect from after-dinner and

We have all seen how their

fortable attention when th

other occasional speakers.

audiences sit back in com-

‘0 one ex;

Of after-dinner

strings of witty one.

Pects teachers to rival th

speakers or to regale thei.

liners. We are neit

© Most skillful

ir students with

her trained nor e

2019:08114 11:5)

LS

TO A YOUNG TEACHER

Lerrer

paid to be entertainers. What too many teachers fail

to realize, however, is that a touch of humor can be as

valuable in a classroom as in a banquet hall. A school

is not so sacred a setting that occasional giggles and

guffaws are utterly taboo. Anything that relaxes ten-

sion and prevents fatigue is an aid to keeping students

awake and attentive.

It follows that although the fault is not fatal, people

who are deficient in sense of humor are to that degree

deficient as teachers. If you are blessed with even a

slight capacity for creating laughter, cultivate it. Don't

think that the pursuit of light-heartedness and good

cheer is unbecoming one who occupies a teacher's

pedestal. For your students your sense of humor will

lighten the onerous process of learning, and for you

it will brighten many an otherwise gray class day.

lonce had a principal who took offense whenever

he heard peals of laughter coming from one of his

classrooms. He thought it destroyed the austerity that

should permeate a school. In contrast, Gilbert Highet

speaks of a “very wise old teacher” he knew who once

said, “I consider a day's teaching wasted if we do not

all have one hearty laugh” (The Art of Teaching [New

York: Albert A. Knopf; 1959] p- 61), Hiletheei aii

that their laughing together blurred the age-old hos-

tility between young and old, pupil and master me

48

LETTER TO A YOUNG TEacter

prompted a piece of advice I received from a veteran

teacher when | was about to begin my teaching ca-

reer: “Don't crack a smile for your first six months.”

That injunction certainly went too far, and | knew

enough not to take it literally. But it contained a

potent grain of wisdom, The peril for novice teachers

is real. Fora while they should go easy on the humor.

Onee a teacher loses control of a class, there is no

regaining it. The game is over.

Second, never indulge in the humor of ridicule at

the expense of a student's feelings. Some gentle rib-

bing may be allowable, provided you are certain the

student will know you are not serious and will take it

with a smile, But sarcasm is never in place, especially

sarcasm aimed at a pupil's mental deficiencies.

Finally, beware of canned humor, the kind one

expects to find in a joke book. The problem is not

that rehearsed humor is inherently out of place in the

classroom, but that few non-professionals know how

to tell such jokes effectively. Don’t even try unless you

are certain you are one of these few. The rest of us

* ae ae rwe

usually find that either our timing is badly off a

chline.

cannot handle the dialogue or we muff the oe -

‘ ine for a pro-

Creating the kind of humor that is routine

i i ired slowly and by

fessional entertainer is a skill acqu have

When and if you n@

most people never at all.

50

Humor

acquired it, you will know. When in doubt, you al-

most certainly haven't.

So far I have used the word “humor’ in the sense of

something that produces laughter. The word has another

meaning, however, as when a student says, "My teacher

was ina very good humor today.” This kind of humorall

teachers, even those genetically incapable of telling a

joke or relating a funny anecdote properly, have the

Power to create every time they face a class. All it takes

is a friendly, unthreatening, easygoing manner. Such a

manner creates an atmosphere that makes school a plea-

sure, a place where the pill of knowledge goes down

easily. When the teacher is stern in manner the stu-

dents grow tense, attention slackens, and little sinks in

To generate this friendly atmosphere it helps enor-

mously to learn the names of all your students as early

in the term as possible. This may not be as easy as it

sounds, especially if the class is large or has many ex-

otic names. You may find it necessary to make a chart

of where each student is seated and have them keep

the same seats until you no longer need the chart.

Whatever trouble this takes is well worth it. Once

you know and call each student by name, the atmos-

phere of your class will grow homey and family-like.

Your students will no longer be an anonymous mass

but individuals, each with a unique personality.

to ances

>

LETTER PO Ay WOUNG TEACHER

The price the teacher has to pay for favoring an

atmosphere of good humor in the classroom may be a

slight relaxation of discipline. If this happens, do not

be alarmed. A teacher is not a guard in a prisoner-of.

war camp. Allowing an occasional remark from the

floor and ignoring a little whispering in the back

seats are not necessarily formulas for disaster. To mix

a metaphor, keep a steady hand on the till, but don't

crack the whip at the slightest infraction.

One important way to show good humor in the

classroom is by praising your students, both individu-

ally and collectively, when they do a good job. This

costs you nothing and often gives a tremendous lift to

the students, making them more attentive and ambi-

tious to succeed. Too many teachers try to scold their

pupils into better study habits. Praising them may not

achieve all the benefits you desire, but nagging them

never works

When | taught English, I routinely assigned for the

weekend a short essay. After correcting these with

appropriate remarks in the margin, I would spend some

time commenting in class on the more interesting Ones-

| always saved the best for the last, reading parts aloud

with suitable praise and announcing that the ane

(and totally imaginary) literary

y weekly

had won my wee niet ean he

award (designated the “Landy

52

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ausubel: Meaningful Reception LearningDocument18 pagesAusubel: Meaningful Reception LearningBernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet

- David Ausubel Pps - PpsDocument18 pagesDavid Ausubel Pps - PpsBernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet

- Ingredients 1 Batch 2 Batches: CCCP I NOODLES (Cooking)Document5 pagesIngredients 1 Batch 2 Batches: CCCP I NOODLES (Cooking)Bernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet

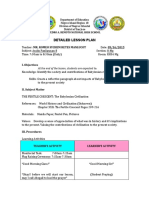

- Detailed Lesson Plan: I. ObjectivesDocument9 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan: I. ObjectivesBernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet

- Knives-Lesson 1: Learner ObjectivesDocument3 pagesKnives-Lesson 1: Learner ObjectivesBernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet