Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beach Tourism: March 2017

Uploaded by

Aa NaldiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beach Tourism: March 2017

Uploaded by

Aa NaldiCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/323596155

Beach Tourism

Chapter · March 2017

CITATIONS READS

0 7,915

1 author:

Felicity Picken

Western Sydney University

33 PUBLICATIONS 62 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Oceans, Space and Society: Towards a Blue Sociology (with Palgrave Macmillan) View project

Encountering the Other: Public Aquaria in Australia View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Felicity Picken on 07 March 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The SAGE International Encyclopedia of

Travel and Tourism

Beach Tourism

Contributors: Felicity Picken

Edited by: Linda L. Lowry

Book Title: The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

Chapter Title: "Beach Tourism"

Pub. Date: 2017

Access Date: March 6, 2018

Publishing Company: SAGE Publications, Inc

City: Thousand Oaks

Print ISBN: 9781483368948

Online ISBN: 9781483368924

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483368924.n51

Print pages: 135-136

©2017 SAGE Publications, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

This PDF has been generated from SAGE Knowledge. Please note that the pagination of

the online version will vary from the pagination of the print book.

SAGE SAGE Reference

Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com.

Beach tourism is one of the earliest modern forms of tourism and a staple of the tourism

industry. This kind of tourism at coastal resorts is often considered to result from an inevitable

attraction to the beach, but the relationship is one in which tourism and leisure are an

inherent part of the formation of the desirability of beaches. As a resort-styled destination, the

beach is almost synonymous with the makings of modern tourism. This is partly because the

beach as a desirable pleasure space did not become notable until the 19th century, following

the defeat of sentiments of danger and strangeness through its gradual reinvention as a

coastal resort and playground for pleasure.

Beginning with the cool beaches of the north and spreading to the warmer beaches beyond,

first the wealthy requiring a cure, then the mass day-trippers on trains and families on

holidays, and now international tourists of various types make up the market of one of the

most successful forms of tourism. Today’s mature beach tourism sector, where high-amenity

lifestyles describe the pleasure of sun, sea, surf, and sex, is a recent, if highly popular,

invention.

Development of Beach Tourism

Although pleasurable beaches have become naturalized and seemingly inevitable, they were

developed through distinctly modern principles and rules of engagement. Cautionary tales of

the sea and coast have a longer history than modernity and modern forms of travel. Today’s

taken-for-granted coastal attraction was inconceivable as little as 200 years ago and

depended on cultural processes that demystified coastal areas, first as medicinal havens for

the wealthy in the early development of popular resorts.

Before this, the Judeo-Christian coast, for example, was always the result of catastrophe, a

remnant of ruination caused by the destructive force of the Biblical flood putting an end to the

paradisiacal Eden. At this time, the sea was a mysterious and dangerous place, unknown and

unknowable, sporadically delivering havoc on land that was completely alien to it. Religious

belief, alongside the persistent knowledge of superstition and myth, continued to align the

beach with danger and undesirability. This incited distrust and fear until the Enlightenment,

challenging both of these, marked the beginnings of a modern system of appreciation.

Image 1 From the shore of a beach resort, visitors watch waves in Cancún, Mexico.

While the original appeal of beach tourism involved cooler climates, warmth and

sunshine now define beach tourism’s appeal.

Page 2 of 6 The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

SAGE SAGE Reference

Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com.

Source: Richard Wilkie

Once freed from narratives of “the fall” and opened up to a scientific gaze, people were able

to relate to the sea in a rational as well as romantic way, the latter most notable through the

aesthetic of the sublime. Science and technology began to tame, harness, and exploit the

coast for the uncontested improvement and advancement of modern “empire,” as oceans

began to connect and globalize the territories of the world rather than disconnect and

regionalize them. Sublimity and science opened up a beach that became both safe and

poetic, setting the stage for what we recognize as beach tourism today.

In remaining somewhat undisciplined, the appeal of the beach as a place of pleasure and

also for liminal experiences was able to develop. The restless movement of the sea served as

a reference point to its unpredictable and tempestuous nature that, crucially, formed the basis

of excitement that propelled the allure of the beach as a space for reinvention, rejuvenation,

and recreation.

In the second half of the 20th century, this liminality transpired through the gradual

popularization of surfing, nudism, and rituals associated with sexual experimentation and the

spectacle of the body freed from usual attire and placed on display. The warm climates soon

gained appeal over earlier cool beach resorts in the United Kingdom, adding to the

languorous and relaxing properties of the beach and permission to invert the everyday

realities of predominantly urban, noncoastal life.

Before this, the earliest developments of beach tourism began as a form of health tourism as

people were drawn out from rapidly urbanizing hinterlands toward the sea. By the mid-18th

century, the “seaside,” as a comparatively tamed version of the coast, was attracting wealthy

patrons to the curative properties of salt water and sea air. They, and their entourages,

brought with them a set of expectations that developed opportunities for the provision of

services and entertainment in coastal places.

This began the prototypical British seaside resort, putting the curative properties of the

seaside in contrast with the pathological properties of the cities and towns that were

Page 3 of 6 The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

SAGE SAGE Reference

Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com.

undergoing rapid growth through industrialization. Through the twin emphasis on health and

the patronage of the wealthy, darker notions of the sea and coastline became brighter notions

of seasides that were increasingly designed for pleasure. Further popularity followed,

increasing industrialization and literally paving the way to the coast through railways.

Increasing dissatisfaction with the emergent urban way of life was nevertheless met with the

compensatory surge in economic prosperity and increased amounts of leisure, enabling the

first mass tourism to the United Kingdom coast and prototypical seaside resort.

Resort Model of Beach Tourism

During the late 19th and 20th centuries, the diffusion of this U.K. resort model was

successfully transferred to the Mediterranean and Americas. South Africa, New Zealand,

Australia, and Canada spread a universalized aesthetic, a set of activities, motivation, and

model of development for the popularization of beach tourism. This model of development is

well known in the “tourism area life cycle” as proposed by Richard Butler, closely

approximating the product life cycle but attuned to a tourist destination through stages of

exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, and decline or rejuvenation.

This cycle is discernible and often applied to biographies of well-established seaside resorts

such as Brighton and Blackpool in the United Kingdom, Coney Island in the United States,

and Coolangatta in Australia. Combined with the motor vehicle, these resorts soon attracted

family-style tourism, providing the opportunity to get away for summer holidays. Families were

attracted to the beach resort model’s logic of spatial containment where beach tourism

followed a daily staple of activities for parents and children in the safe environs of the resort.

As markets became increasingly differentiated, resorts became ever more elaborate in order to

compete for the annual family holiday. This developed the resort-based approach to beach

tourism into its familiar form today.

Although the U.K. models of beach or seaside tourism were based on cool beaches and

climates, warmer beach resorts soon overtook their popularity and in some cases became

saturated, in the common aim of exploiting the sun, sea, sand, and sex themes in the warm

waters of the Mediterranean region and the Caribbean. Places such as the Riviera Maya in

Mexico, as well as the popular and opulent-styled resorts on the Pacific in places such as

Acapulco and the islands of Hawaii and Fiji, are now successfully rivaled by the popularization

of beach resorts in Southeast Asia, including higher rates of growth in places such as Penang

in Malaysia, Phuket in Thailand, and Bali in Indonesia.

So routine is the opportunity of golden sands for tourism that the prevalence of beach tourism

is difficult to measure. The beach is most often included in measurements of “nature-based

tourism” through activity scales or in visitation to islands or adjacent cities. For example, Bondi

Beach and the Gold Coast are among Australia’s most popular tourist attractions, but visitors

are counted among metropolitan statistics, whereas many of the regional beach areas are

described by rural or ecotourism statistics.

The popularity of the beach resort not only diminishes its distinctiveness in terms of visitor

accounting, but tourist destinations reliant on the resort model have increasingly fallen prey to

the difficulty of differentiation in highly competitive beach destinations. So successful is the

beach as a tourist destination that, increasingly, countries reliant on beach tourism are faced

with the problem of how to maintain distinctiveness when this form of tourism has become so

routinized.

Page 4 of 6 The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

SAGE SAGE Reference

Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com.

New tourist practices and trends are now pushing the limits of beach tourism in the opposite

direction, developing complementary hinterland attractions, including rural, culinary, and wine

tourism as well as increasingly developing attractions “out to sea.” This expanded horizon of

pleasure beyond the literal zone exploits the increasing willingness of tourists to immerse in

undersea environments and encounter new innovative leisure attractions, including

underwater museums, art galleries, restaurants, and hotels. Coastal hinterlands are also

being drawn on to differentiate the limitations of the resort model by expanding the destination

offerings to include adjacent cities or rural areas and diversify the tourist product.

At the same time, coastal areas are increasingly attractive to the competing interest of

residential development as beachfront property vies for a space on the coast and with this,

exclusive rights to adjacent beachfront areas. In these cases, tourist resorts are often

regarded as unruly and unwanted catchments for undesirable behavior with detrimental

environmental and cultural impacts.

As hedonistic expectations and activity incited increased levels of crime, exceeded carrying

capacity, and caused a decline in the quality of desirability of the resort experience, exclusivity

in resort and tourist offerings now seek to replace the masses with more desirable forms of

niche tourism. Relatively underdeveloped coastal areas are then sought at a premium price to

ensure exclusive experiences that generally encompass a more holistic set of experiences that

are not singularly focused on the pleasure beach but offer a range of activities and attractions

aimed at more discerning tourists.

Felicity Picken

See alsoButler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle and Its Expansion to the Creative Economy;

Cancún, Mexico; Culinary Tourism; Fiji; Phuket, Thailand; Wine Tourism

Further Readings

Butler, R. (2004). The tourism area life cycle in the 21st century. In A. Lew, C. M. Hall, & A.

Williams (Eds.), A companion to tourism (pp. 159–170). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Corbin, A. (1994). The lure of the sea: The discovery of the seaside in the Western world.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Demars, S. (1979). British contributions to American seaside resorts. Annals of Tourism

Research, 6(3), 285–293.

Franklin, A., Picken, F., & Osbaldiston, N. (2013). The changing nature of the Australian

beach tourism in a low carbon society. International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and

Responses, 5(1), 1–10.

Hunstman, L. (2001). Sand in our souls. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

Laderman, S. (2014). Empire in waves: A political history of surfing. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Obrador Pons, P., Crang, M., & Travlou, P. (2009). Cultures of mass tourism: Doing the

Mediterranean in the age of banal mobilities. Surrey, England: Ashgate.

Page 5 of 6 The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

SAGE SAGE Reference

Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com.

Preston-Whyte, R. (2001). Constructed leisure space: The seaside at Durban. Annals of

Tourism Research, 28(3), 581–596.

Shields, R. (1991). Places on the margin: Alternative geographies of modernity. London,

England: Routledge.

Travis, J. (1993). The rise of the Devon seaside resort: 1750–1900. Devon, England: University

of Exeter Press.

Urbain, J.-D. (2003). At the beach (C. Porter, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press.

tourism

beaches

resort

seaside resorts

seas

coasts

coastal areas

Felicity Picken

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483368924.n51

10.4135/9781483368924.n51

Page 6 of 6 The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

View publication stats

You might also like

- From a bag of chips to cod confit: a tour of twenty English seaside resortsFrom EverandFrom a bag of chips to cod confit: a tour of twenty English seaside resortsNo ratings yet

- 2 Nature and Seaside ArchitectureDocument30 pages2 Nature and Seaside ArchitectureMaria ArionNo ratings yet

- The World's Beaches: A Global Guide to the Science of the ShorelineFrom EverandThe World's Beaches: A Global Guide to the Science of the ShorelineNo ratings yet

- Unit-14 Beach and Island Resorts Kovalam and LakshadweepDocument17 pagesUnit-14 Beach and Island Resorts Kovalam and LakshadweepAnannya RNo ratings yet

- Beach Complex Research 2Document28 pagesBeach Complex Research 2leoncitorhealyn23No ratings yet

- Sustainability 13 13903Document15 pagesSustainability 13 13903Bea ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Insight Guides Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles (Travel Guide eBook)From EverandInsight Guides Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles (Travel Guide eBook)No ratings yet

- Pathways Summer 2014 - Digital-2Document11 pagesPathways Summer 2014 - Digital-2NYSOEANo ratings yet

- Maritime Heritage Tourism and Sea Grants From NOAA - The Sea Grant Sustainable Coastal Community Development BulletinDocument4 pagesMaritime Heritage Tourism and Sea Grants From NOAA - The Sea Grant Sustainable Coastal Community Development BulletinLee WrightNo ratings yet

- Definition of Beauty EssayDocument5 pagesDefinition of Beauty Essayertzyzbaf100% (2)

- Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of GeorgiaFrom EverandViews of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of GeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Tiếng anh ÍnDocument2 pagesTiếng anh ÍnSu MiNo ratings yet

- Orams (2003) Sandy Beaches As A Tourism Attraction A Management Challenge For The 21st CenturyDocument11 pagesOrams (2003) Sandy Beaches As A Tourism Attraction A Management Challenge For The 21st CenturyOrlandoNo ratings yet

- Thesis FinalDocument20 pagesThesis FinalMac MelencionNo ratings yet

- Sun Lust to Sun Plus: Niche Tourism in the CaribbeanFrom EverandSun Lust to Sun Plus: Niche Tourism in the CaribbeanAcolla Lewis-CameronNo ratings yet

- Ogunquit Leads The Way:: Stewardship of "The Beautiful Place by The Sea"Document26 pagesOgunquit Leads The Way:: Stewardship of "The Beautiful Place by The Sea"Jason VillaNo ratings yet

- Franklin 2014Document25 pagesFranklin 2014Boris ĐipaloNo ratings yet

- SFA Newsletter Summer 2020-2021Document28 pagesSFA Newsletter Summer 2020-2021Sandringham Foreshore AssociationNo ratings yet

- 2016 3 4 2 JonesDocument14 pages2016 3 4 2 JonesSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- The Last Resort: A Chronicle of Paradise, Profit, and Peril at the BeachFrom EverandThe Last Resort: A Chronicle of Paradise, Profit, and Peril at the BeachRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- History of Travel and TourismDocument6 pagesHistory of Travel and TourismInes Barrelas100% (1)

- Schoodic Point: History on the Edge of Acadia National ParkFrom EverandSchoodic Point: History on the Edge of Acadia National ParkNo ratings yet

- Managing Lake Tourism: Challenges AheadDocument12 pagesManaging Lake Tourism: Challenges AheadPresa Rodrigo Gómez, "La Boca"100% (1)

- Heritage or Heresy: Archaeology and Culture on the Maya RivieraFrom EverandHeritage or Heresy: Archaeology and Culture on the Maya RivieraNo ratings yet

- World Heritage SiteDocument4 pagesWorld Heritage SiteMoisestoshNo ratings yet

- Excerpt: "The Mortal Sea" by W. Jeffrey BolsterDocument5 pagesExcerpt: "The Mortal Sea" by W. Jeffrey BolsterSam Gale RosenNo ratings yet

- The Last Beach by Orrin H. Pilkey and J. Andrew G. CooperDocument44 pagesThe Last Beach by Orrin H. Pilkey and J. Andrew G. CooperDuke University Press100% (1)

- 1st PaperDocument14 pages1st PaperKOPSIDAS ODYSSEASNo ratings yet

- The Riviera, Exposed: An Ecohistory of Postwar Tourism and North African LaborFrom EverandThe Riviera, Exposed: An Ecohistory of Postwar Tourism and North African LaborRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Enjoying Your Beach and Cleaning It Too A Grounded Theory Ethnography of Enviro Leisure ActivismDocument21 pagesEnjoying Your Beach and Cleaning It Too A Grounded Theory Ethnography of Enviro Leisure ActivismBoris ĐipaloNo ratings yet

- Blue Urbanism: Exploring Connections Between Cities and OceansFrom EverandBlue Urbanism: Exploring Connections Between Cities and OceansRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (1)

- Ocean-Aquariums and Their Visitor Experiences: An Instrument For Promoting Tourism and Aquatic Wildlife ConservationDocument8 pagesOcean-Aquariums and Their Visitor Experiences: An Instrument For Promoting Tourism and Aquatic Wildlife ConservationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Boat Building and Boat Yards of Long Island: A Tribute to TraditionFrom EverandBoat Building and Boat Yards of Long Island: A Tribute to TraditionNo ratings yet

- 1 SAGO Ltd. "The History of Hotels From Economic To Extravagant"Document11 pages1 SAGO Ltd. "The History of Hotels From Economic To Extravagant"Alvin YutangcoNo ratings yet

- The Edge: The Pressured Past and Precarious Future of California's CoastFrom EverandThe Edge: The Pressured Past and Precarious Future of California's CoastNo ratings yet

- 1 Ang Giving A Talk TravelDocument4 pages1 Ang Giving A Talk TravelaxakesNo ratings yet

- Saving the Reef: The human story behind one of Australia’s greatest environmental treasuresFrom EverandSaving the Reef: The human story behind one of Australia’s greatest environmental treasuresNo ratings yet

- Harris, L. (2017) Sea Ports and Sea PowerDocument125 pagesHarris, L. (2017) Sea Ports and Sea PowerAlejandro DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in The Development of Tourist Attractions: April 2012Document9 pagesCurrent Trends in The Development of Tourist Attractions: April 2012beeeeeNo ratings yet

- Southern Journeys: Tourism, History, and Culture in the Modern SouthFrom EverandSouthern Journeys: Tourism, History, and Culture in the Modern SouthNo ratings yet

- The Whale in The Cape Verde Islands SeasDocument18 pagesThe Whale in The Cape Verde Islands SeasermouafoNo ratings yet

- History of TravelDocument2 pagesHistory of Traveltinanunez_104843No ratings yet

- SFA Newsletter Autumn 2021Document25 pagesSFA Newsletter Autumn 2021Sandringham Foreshore AssociationNo ratings yet

- Rea Nica Gerona - TPC7 MODULE 1 ACTIVITY - CASE STUDYDocument7 pagesRea Nica Gerona - TPC7 MODULE 1 ACTIVITY - CASE STUDYRea Nica GeronaNo ratings yet

- Essay On BeachesDocument2 pagesEssay On Beachessimaak soudagerNo ratings yet

- Two Sides of Tourism 19470Document1 pageTwo Sides of Tourism 19470Rosália Fernandes100% (1)

- Attraction, Tourism: TouristDocument4 pagesAttraction, Tourism: TouristAzyyati N. ZahraNo ratings yet

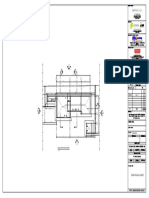

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

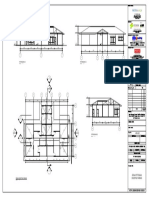

- Potongan A-A Potongan C-C: Detail Engineering DesignDocument1 pagePotongan A-A Potongan C-C: Detail Engineering DesignAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Detail Engineering Design: PertamedikaDocument1 pageDetail Engineering Design: PertamedikaAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Potongan A-A Potongan C-C: Detail Engineering DesignDocument1 pagePotongan A-A Potongan C-C: Detail Engineering DesignAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Architecture and Human Senses: R.RagavendiraDocument5 pagesArchitecture and Human Senses: R.RagavendiraAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Architecture and Human Senses: R.RagavendiraDocument5 pagesArchitecture and Human Senses: R.RagavendiraAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Site 1Document1 pageSite 1Aa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Example of Building DrawingDocument1 pageExample of Building DrawingAa NaldiNo ratings yet

- DNH lt1Document1 pageDNH lt1Aa NaldiNo ratings yet

- Suriname Food Security Policy and InitiativesDocument11 pagesSuriname Food Security Policy and InitiativesJamal BakarNo ratings yet

- BOM IXC: TICKET - ConfirmedDocument3 pagesBOM IXC: TICKET - ConfirmedSudarshan KulkarniNo ratings yet

- How To Identify Fake 50 Rupee Currency NotesDocument12 pagesHow To Identify Fake 50 Rupee Currency NotesPolisettyNo ratings yet

- 4 - List of AbbreviationsDocument5 pages4 - List of AbbreviationsMehtab AhmedNo ratings yet

- Annex 30-XXXII of Instruction No. 480/09 of CVMDocument9 pagesAnnex 30-XXXII of Instruction No. 480/09 of CVMMillsRINo ratings yet

- Chapter-1 Techinical AnalysisDocument90 pagesChapter-1 Techinical AnalysisRajesh Insb100% (1)

- Elevator Speech 2Document1 pageElevator Speech 2api-405930625No ratings yet

- Account Number: Abdu Arya 911 Turnpike RD Claxton Ga 30417 Office Serving You M1 FinanceDocument2 pagesAccount Number: Abdu Arya 911 Turnpike RD Claxton Ga 30417 Office Serving You M1 FinanceAbdu AryaNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Passage-3 Read The Passage Carefully and Answer The FollowingDocument2 pagesReading Comprehension Passage-3 Read The Passage Carefully and Answer The FollowingadiG48 AtdiG48No ratings yet

- Chapter 6 and 7 NR and BPDocument2 pagesChapter 6 and 7 NR and BPCa Ada100% (1)

- Token Numbers List PDFDocument87 pagesToken Numbers List PDFParkashNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 Test Bank PDFDocument29 pagesChapter 15 Test Bank PDFCharmaine Cruz100% (1)

- MDP Export and ImportDocument6 pagesMDP Export and Importjooner45No ratings yet

- Sector Update India Cement April 2018Document120 pagesSector Update India Cement April 2018Vivek PatidarNo ratings yet

- Permission To Pay Quartelry A Proportion of The Normal Registration Tax - Skat DenmarkDocument1 pagePermission To Pay Quartelry A Proportion of The Normal Registration Tax - Skat DenmarkIoan NaturaNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management - Introduction - Session 1 & 2Document56 pagesWorking Capital Management - Introduction - Session 1 & 2Vaidyanathan RavichandranNo ratings yet

- 523 383 1 PB PDFDocument97 pages523 383 1 PB PDFs.muthuNo ratings yet

- Process Presentation Slides: Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet, Consectetur Adipiscing Elit. Aliquam Eu Lobortis ErosDocument14 pagesProcess Presentation Slides: Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet, Consectetur Adipiscing Elit. Aliquam Eu Lobortis ErosTheJoemsiNo ratings yet

- 2016 Economics H2 JC2 Pioneer Junior CollegeDocument14 pages2016 Economics H2 JC2 Pioneer Junior CollegeSebastian ZhangNo ratings yet

- Palm Oil Plantation 2012Document12 pagesPalm Oil Plantation 20122oooveeeNo ratings yet

- Pi 28-2102s-Single High Speed SKD - Pi-A StatorDocument1 pagePi 28-2102s-Single High Speed SKD - Pi-A StatorRajesh RoyNo ratings yet

- New 4Document49 pagesNew 4katariya_anujaNo ratings yet

- Amante, Kevin Q. Essay 2 JD3 April 22, 2018Document4 pagesAmante, Kevin Q. Essay 2 JD3 April 22, 2018Kevin AmanteNo ratings yet

- CA Booking FormDocument3 pagesCA Booking FormSkand SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- 5 - Indonesia 493Document26 pages5 - Indonesia 493thanhnguyet.vietcraftNo ratings yet

- Linear Regression Example PDFDocument5 pagesLinear Regression Example PDFbingoNo ratings yet

- Jack Daniel'sDocument17 pagesJack Daniel'sIon TarlevNo ratings yet

- Southern Railway Timetable PDFDocument423 pagesSouthern Railway Timetable PDFSriram SriramNo ratings yet

- Od116961664643580000 PDFDocument3 pagesOd116961664643580000 PDFRisi Spice industriesNo ratings yet

- FATCA User Guide ReportingDocument26 pagesFATCA User Guide ReportingMousNo ratings yet

- The Food Almanac: Recipes and Stories for a Year at the TableFrom EverandThe Food Almanac: Recipes and Stories for a Year at the TableRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Stargazing: Beginner’s guide to astronomyFrom EverandStargazing: Beginner’s guide to astronomyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Everyday Guide to Special Education Law: A Handbook for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals, Third EditionFrom EverandThe Everyday Guide to Special Education Law: A Handbook for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals, Third EditionNo ratings yet

- Purposeful Retirement: How to Bring Happiness and Meaning to Your Retirement (Retirement gift for men)From EverandPurposeful Retirement: How to Bring Happiness and Meaning to Your Retirement (Retirement gift for men)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The World Almanac Road Trippers' Guide to National Parks: 5,001 Things to Do, Learn, and See for YourselfFrom EverandThe World Almanac Road Trippers' Guide to National Parks: 5,001 Things to Do, Learn, and See for YourselfNo ratings yet

- Publishers Weekly Book Publishing Almanac 2022: A Master Class in the Art of Bringing Books to ReadersFrom EverandPublishers Weekly Book Publishing Almanac 2022: A Master Class in the Art of Bringing Books to ReadersNo ratings yet

- 71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Brilliant Bathroom Reader (Mensa®): 5,000 Facts from the Smartest Brand in the WorldFrom EverandBrilliant Bathroom Reader (Mensa®): 5,000 Facts from the Smartest Brand in the WorldNo ratings yet

- Restore Gut Health: How to Heal Leaky Gut Naturally and Maintain Healthy Digestive SystemFrom EverandRestore Gut Health: How to Heal Leaky Gut Naturally and Maintain Healthy Digestive SystemNo ratings yet

- Seasons of the Year: Almanac for Kids | Children's Books on Seasons EditionFrom EverandSeasons of the Year: Almanac for Kids | Children's Books on Seasons EditionNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence: How to Improve Your IQ, Achieve Self-Awareness and Control Your EmotionsFrom EverandEmotional Intelligence: How to Improve Your IQ, Achieve Self-Awareness and Control Your EmotionsNo ratings yet