Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Health Financing in Indonesia: A Reform Road Map

Health Financing in Indonesia: A Reform Road Map

Uploaded by

Vita WidyasariCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Health Financing in Indonesia: A Reform Road Map

Health Financing in Indonesia: A Reform Road Map

Uploaded by

Vita WidyasariCopyright:

Available Formats

FACT SHEET

Health Financing in Indonesia: A Reform Road Map

Indonesia has made major improvements in health outcomes

Health outcomes have improved significantly since 1980 when life expectancy was only 52 years compared to almost 70 today,

and some 100 infants out of every 1000 died before their first birthday, compared to less than 30 today. The total fertility rate has

declined from 4.7 children per woman to slightly above 2. Despite these impressive improvements, Indonesia’s achievements

have been less impressive than some of its neighbors, and for certain health outcomes, such as maternal mortality, the country

does not perform as well as other comparable income and health spending level countries.

Indonesia’s health delivery capacity has expanded significantly

Indonesia’s health delivery system expanded significantly over the past 40 years. Virtually all Indonesian’s have access to basic

care through a network of 8000 Puskesmas and 22,200 Puskesmas Pembantu, and some 5,800 mobile health clinics. On the other

hand, while Indonesia has far fewer hospital beds per capita compared to other comparable income countries, these beds are

poorly utilized with occupancy rates on the order of 60 percent. In terms of human resources for health, while nurse mid-wives

are readily available throughout the country, Indonesia’s health workforce overall is small relative to other similar income

countries and concerns over quality and efficiency persist. Its physician workforce is very small relative to comparators, and there

are severe shortages of specialists, which are particularly problematic given the proposed expansions in health insurance

coverage and the oncoming non-communicable disease burden. There are serious equity, quality, and efficiency problems

underlying Indonesia’s current health delivery system which, unless corrected, will result in major access, cost, and sustainability

problems as the country moves to universal health insurance coverage.

Indonesia’s health spending is relatively low and the country gets reasonable ‘value for money’ in terms of some health

outcomes as well as relatively good financial protection

Indonesia spends only slightly more than 2 percent of its GDP on health, about half the level of other comparable income

countries. Half of all health spending is public. About one-third of health spending comes directly from of out of pocket

payments by households. Health is a relatively small share of the government’s budget, some 5 percent, although the share has

been increasing since the implementation of the Askeskin program in 2004. Despite low spending health outcomes and financial

protection are relatively good, although these latter results may be due to Indonesia’s relatively high education levels and

extended family social structure. On the other hand, some health outcomes such as maternal mortality, which is dependent on a

well functioning health system, are worse than other comparators and analyses of technical efficiency suggest that there are some

potentially serious problems.

The reform needs to build on the system’s strength’s and address its weaknesses

The report documents the health system’s strengths and weaknesses based on empirical analyses of health spending, health

outcomes, financial protection, consumer responsiveness, quality, equity, and efficiency.

Strengths Weaknesses

Favorable demographic circumstances Half the population lacks health insurance coverage

High educational and literacy levels Government health subsidies disproportionally benefit

Government commitment for reform the rich

Low levels of health spending Health financing and delivery systems are highly

Reasonable financial protection and consumer fragmented

satisfaction Some health outcomes are poor

Experience with health insurance programs Demographic, epidemiological, and nutrition transitions

An extensive primary care delivery system will place significant pressures on future health care

Generally good availability of pharmaceuticals. costs and delivery system needs

Significant geographic disparities in health outcomes,

availability and use of services persist

Human and physical infrastructures are limited and face

quality and efficiency problems

Significant improvements in the quality and costs of

pharmaceuticals, which account for some one-third of

health spending, are needed

Decentralization has confused the roles and

responsibilities of the different levels of government and

the intergovernmental transfer system does not yet fully

recognize differences in need and fiscal capacity

For more information on the World Bank’s program,

visit: www.worldbank.org/id

Critical data for decision-making are lacking

Design features of the Jamsostek and Askes programs

result in high out of pocket costs for program

beneficiaries and preclude effective operation

No comprehensive studies of the health outcome and

financial impacts, real costs, and future sustainability of

the Askeskin/Jamkesmas programs.

Indonesia’s reform process needs to address both broad policy concerns such as the final system design and transition

options as well as numerous ‘devils in the details’ including the design of the basic benefits package; groups eligible for

public subsidies; identification and collection of premiums from informal sector workers; how medical care providers

will be paid; how the reform will be financed; who will administer the program; and, how will better health outcomes,

financial protection, consumer responsiveness, quality, efficiency, equity, and financial sustainability be assured.

While the Government has made some important progress in developing draft laws to implement the Social Security Reform Law

40/2004, the report notes that much additional work needs to be done. It also highlights the need for the Government to specify

its final vision for universal coverage and develop and cost the various transition options and timing to get there. It highlights

several potential final visions including a single national mandatory health insurance system where the government subsidizes the

poor and other disadvantaged groups as in Turkey, Thailand, Columbia, and Chile as well as a ‘Jamkesmas for all’ approach

which is fully financed by the government and very much approximates the national health service systems in Sri Lanka and

Malaysia. Development of the transition options and final reform impacts will require specification of key program details. The

report develops a policy framework for addressing the key policy issues requiring resolution based on the system’s strengths and

weaknesses, Indonesia-specific and international experience, and underlying public health, health insurance, health economics

and public finance principles.

The report also focuses heavily on the need for solid actuarial analyses of the costs and revenues of the various options and the

challenge to the government to assure sustainability of the reform within its available future fiscal space. If upon achieving

universal coverage Indonesia’s spending jumps to the level in other comparable income countries and Indonesia faces the cost

pressures of the industrialized countries, health spending in 2040 could reach almost 10 percent of GDP compared to just over 2

percent today. If the government can hold future cost pressures to their historic rates of increase, then spending well be on the

order of 6 percent of GDP. The report highlights the importance of getting the key design elements of the reform ‘right’, a rather

complex policy challenge given the interactions among reform components as well as Indonesia’s socioeconomic situation which

includes a large number of poor, much of the population living in rural areas, a high percentage of informal sector workers, and a

large number of very small firms.

For more information on the World Bank’s program,

visit: www.worldbank.org/id

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Consulting Casebook MckinseyDocument84 pagesConsulting Casebook MckinseyMaria Pappa100% (2)

- Topic 5 Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument7 pagesTopic 5 Corporate Social Responsibilitymoza salim100% (1)

- Toward A New World Order by George SorosDocument12 pagesToward A New World Order by George SorosrexxturboNo ratings yet

- INCOTERMS 2010 - Illustrated GuideDocument28 pagesINCOTERMS 2010 - Illustrated Guidevarun_nayak_167% (3)

- ISO 14041: Environmental Management - Life Cycle Assessment - Goal and Scope Definition - Inventory AnalysisDocument1 pageISO 14041: Environmental Management - Life Cycle Assessment - Goal and Scope Definition - Inventory AnalysisSrikanth MeesaNo ratings yet

- Cost Calculation TCG 2020 V16K With CNGDocument2 pagesCost Calculation TCG 2020 V16K With CNGR_afflyNo ratings yet

- Bagasse Based CogenerationDocument13 pagesBagasse Based CogenerationknsaravanaNo ratings yet

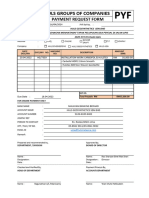

- PRF - SupplierDocument18 pagesPRF - Supplierdeanwolves16No ratings yet

- Iron and Steel Industry Report 2018 enDocument28 pagesIron and Steel Industry Report 2018 enAlexei AlinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 QuizDocument9 pagesChapter 9 QuizRaven PicorroNo ratings yet

- Bills of Exchange Bill emDocument5 pagesBills of Exchange Bill emBlue HughesNo ratings yet

- Contabilidad. Plantilla Inventario AnalíticoDocument14 pagesContabilidad. Plantilla Inventario AnalíticoRubenSanchezLopezNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument4 pagesMultiple Choice QuestionsErlina MasoenNo ratings yet

- Coursenotes BFB4133-090212 102219Document101 pagesCoursenotes BFB4133-090212 102219Makisha NishaNo ratings yet

- 2 - P. S. Sikarwar EnterprisesDocument1 page2 - P. S. Sikarwar Enterprisespriyanka singhNo ratings yet

- Domestic Production and Foreign Trade The American Capital Position Re-ExaminedDocument23 pagesDomestic Production and Foreign Trade The American Capital Position Re-ExaminedKevin Mcdonald100% (2)

- Agricultural Economics Exam Bank SummaryDocument66 pagesAgricultural Economics Exam Bank SummaryTsion GetuNo ratings yet

- GSE EnVision UsersListDocument2 pagesGSE EnVision UsersListasamad54No ratings yet

- Introduction On The Study of GlobalizationDocument7 pagesIntroduction On The Study of GlobalizationJezalen GonestoNo ratings yet

- 2014 GIST Tech-I Marrakech BrochureDocument92 pages2014 GIST Tech-I Marrakech BrochureAmandaNo ratings yet

- Migrants' Election ManifestoDocument2 pagesMigrants' Election ManifestoMimi Panes - CorosNo ratings yet

- National Housing Policy (NHP) - 1998Document2 pagesNational Housing Policy (NHP) - 1998Ms. Sangeetha Priya I Assistant Professor I - SPADENo ratings yet

- Environment CASE STUDYDocument2 pagesEnvironment CASE STUDYNosheen JillaniNo ratings yet

- The Legatum Prosperity Index™ 2017Document2 pagesThe Legatum Prosperity Index™ 2017Sputnik MoldovaNo ratings yet

- Sistemas de EcuacionesDocument5 pagesSistemas de EcuacionesRafaNo ratings yet

- Bond YieldsDocument27 pagesBond YieldsSagar TanejaNo ratings yet

- IQSK Issue 31 - April - June 2021 Journal EditionDocument50 pagesIQSK Issue 31 - April - June 2021 Journal Editionbenson njihiaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of MacroeconomicsDocument13 pagesA Brief History of Macroeconomicsزهير استيتوNo ratings yet

- Banyan HydraulicsDocument1 pageBanyan HydraulicsmshNo ratings yet

- Function of Households Reading, Matching, Multiple ChoiceDocument2 pagesFunction of Households Reading, Matching, Multiple ChoiceMikias TewachewNo ratings yet