Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Injunction Granted in Dispute Over POWER 107 Name

Uploaded by

Anonymous NbMQ9Ymq0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4K views20 pagesA copy of the judge's decision to grant an injunction preventing Harvard Broadcasting from using the POWER brand.

Original Title

Injunction granted in dispute over POWER 107 name

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA copy of the judge's decision to grant an injunction preventing Harvard Broadcasting from using the POWER brand.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4K views20 pagesInjunction Granted in Dispute Over POWER 107 Name

Uploaded by

Anonymous NbMQ9YmqA copy of the judge's decision to grant an injunction preventing Harvard Broadcasting from using the POWER brand.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 20

NOY 1 8 2019

Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta

Citation: Corus Radio Inc v Harvard Broadcasting Inc, 2019 ABQB 880

Date:

Docket: 1901 12762

Registry: Calgary

Between:

Corus Radio Inc. and Corus Entertainment Inc.

Plaintiffs

~and -

Harvard Broadcasting Inc.

Defendant

Reasons for Decision

of the

Honourable Madam Justice N. Dilts

IL. Introduction

[1] Corus Radio Ine. and Corus Entertainment Ine. (“Corus”) bring an application for an

interlocutory injunction to restrain Harvard Broadcasting Inc. (“Harvard”) from, amongst other

things, using the POWER 107 name or logo in its radio broadcasting business.

[2] Corus says that when Harvard rebranded its CINW-FM Edmonton radio station in

August 2019 from HOT 107 to POWER 107, changing the station’s name, logo, slogan, music

format, and advertising and promotional materials, it wrongfully traded on the reputation and

goodwill of the POWER radio brand that Corus built over more than a decade in the Edmonton.

‘market and longer elsewhere in Canada, In doing so, Corus says that Harvard wrongfully took

Page: 2

Corus’ opportunity to use the POWER radio brand in the future, and violated laws respecting the

protection of copyright and trademarks, the law of passing off, and unfair competition. It says if

an injunction is not issued, it will suffer irreparable harm in two ways. First, Corus says it has

and will continue to suffer irreparable damage to the ratings of its current station CHUCK 92.5,

formerly POWER 92; second, Corus says it will lose the opportunity to use its existing goodwill

to reintroduce a POWER radio station into the Edmonton market.

(3] Harvard says Corus is not entitled to an interlocutory injunetion. It says Corus has not

met the onus to prove that it is entitled to copyright over its logo, or to protection of its

trademarks. Harvard also says Corus has failed to prove with clear and non-speculative evidence

that it has current goodwill in the POWER 92 brand, that there is any listener confusion that has

caused a loss of goodwill, or that it has suffered irreparable harm as a result of Harvard’s launch

of the POWER 107 station. Harvard says that the success of its POWER 107 station is a result of

the station’s frequency and music format and that if there is listener nostalgia, it relates to the

music it plays.

I Background

[4] Both Corus and Harvard are long-standing members of the Canadian radio industry.

[5] Corus was founded in 1999 and currently operates 39 radio stations across the country,

cluding CHUCK 92.5 in Edmonton and POWER 97 in Winnipeg.

[6] Corus acquired the Edmonton 92.5 FM frequeney in 1999 as part of a large commercial

transaction between it and WIC Western International Communications Ltd. (WIC) and others

(the “WIC Transaction”). In the WIC Transaction, Corus acquired WIC’s radio broadcasting

business which comprised 12 radio stations, including POWER 107 (CKIK) in Calgary, POWER

92 (CKNG) in Edmonton, and POWER 97 (CJKR) in Winnipeg.

[7] __ As part of its acquisition of WIC’s radio broadcasting business, Corus acquired a number

of trademarks, including the following registered trademarks:

POWER 97 word trademark, first used in February 1996 on services and in 1999

‘on goods;

POWER 92 FM Today’s Best Music (Design), known as the POWER 92 Logo,

filed in 1999 and registered in 2003. First used in Canada at least as early as

September 1991 with respect to the operation and promotion of a radio station;

POWER 107 FM Today's Best Music (Design), known as the POWER 107 Logo,

filed in 1999. First used in Canada at least as early as September 1997 with

respect to the operation and promotion of a radio station; and

POWER 97 FM Winnipeg's Rock (Design), known as the POWER 97 Logo, filed

in 1999 and registered in 2003. First used in Canada in 1996 with respect to the

operation and promotion of a radio station,

(the d

[8] Corus also acquired word trademarks in the words “POWER 92” and “POWER 107”;

however, both of those trademarks were automatically expunged from the registry for failure to

ign trademarks collectively referred to as the “trademarked Logos”)

Page: 3

renew. The POWER 92 word trademark was expunged April 30, 2015 and the POWER 107

word trademark was expunged May 7, 2015.

19] The Edmonton CKNG station operated as POWER 92 continuously for over a decade

from 1991 until 2003. POWER 92 was a contemporary hit station, which means it played the

year’s top 40 songs. In March of 1997, Corus introduced POWER 92's Phrase that Pays contest.

In that contest, ifa listener received a call from POWER 92 and was asked for the “Phrase that

Pays”, the listener was required to respond with the phrase “POWER 92 Plays Today’s Best

Music, Now Show Me My Money” to win prize money. While that contest was not unique to

POWER 92, the unique feature was the winning phrase.

[10] In 2003 in response to declining ratings, Corus made changes to the POWER 92 station,

including changing its logo from the POWER 92 Logo, eliminating the tag line “Today’s Best

Music”, and changing its music format. In 2004, Corus rebranded the CKNG station to Joe FM

and changed the music format to classic hits music. The CKNG station continued to operate as

Joe FM until 2013 when it was rebranded as Fresh FM. With that rebranding, the music format

vas changed to hot adult contemporary radio, playing current music plus hits from the last two

decades. The station was once again rebranded in August 2018 and currently operates as

CHUCK 92.5, playing hits from the 1980s to present day.

[11] _ Corus also operated POWER 107 in Calgary from 1997 to 2002, and POWER 97 in

Winnipeg from 1996 to 2015 and from 2016 to present.

[12] Harvard entered the broadcasting industry in 1981 and currently operates 13 radio

stations in Western Canada. It entered the Edmonton radio market in 2010 with the 95.7 FM.

frequency and expanded its presence in that industry in 2011/2012 when it acquired the 107.

FM frequency, then operating as HOT 107. It continues to operate two FM radio frequencies in

Edmonton.

[13] _ HOT 107 was a contemporary hit radio station playing pop and hip-hop musie, and

targeting the younger listening audience. In the summer of 2018, Harvard repositioned its HOT

107 station by changing its music format to contemporary hit music mixed with classic

contemporary hit.

{14] | On August 15, 2019, Harvard rebranded its HOT 107 station to POWER 107, playing

only classic contemporary hits, focusing on hits from the 1990s and 2000s. POWER 107 was

launched with a press release that reads:

Harvard Broadcasting Turns On The Power in Edmonton

There is something POWERfully familiar happening today on 107.1 in Edmonton

as Harvard Broadcasting introduces Power 107 — Edmonton’s Best Music.

Remember when Pop Music was King? When Brittney, Backstreet, Mariah, Spice

Girls, *NSYNC, Destiny’s Child, and Rihanna ruled the charts and airwaves?

Power 107 does.

Starting today on 107.1 FM and online at power107.ca, Power 107 celebrates that

moment in time when Pop music ruled the Edmonton airwaves with something

different yet strangely familiar.

Page: 4

Also familiar will be Power 107’s on air team starting August 26" featuring

Ryder and Lisa, Johnny Infamous, Jake and Hannah, and the return of Gary

James.

Feel the Power!

[15] Harvard launched its POWER 107 station with a new logo and with the tag line

“Edmonton's Best Music”. Harvard’s marketing material included: “POWER 107 Turn the

POWER Back On”, “POWER 107 Feel the POWER Again”; and “POWER 107 plays

Edmonton's Best Music Now Show Me My Money! The return of the #PhraseThatPays

COMING SOON!”

[16] _ Corus complains that these marketing materials and other on-air and on-line postings

from Harvard employees or from the public that were “liked” “re-tweeted” or “re-posted” by

Harvard employees are a deliberate use of Corus’ POWER brand, including its protected

trademarks and copyright.

IIL. General Principles Governing Interlocutory Injunctions

[17] _ Aninterlocutory application is decided before the court has the opportunity to assess all of

the evidence on which the parties might rely at trial. For that reason, a decision on an application

for an interlocutory injunction does not amount to a final determination of the issues.

[18] Every application for an injunction must be assessed in light of the Plaintiff's underlying

claims. Corus’ underlying action is made up of four distinet claims: i) copyright infringement; ii)

trademark infringement; iii) common law passing off; and iv) false and misleading advertising

contrary to the Competition Act. While those claims contain different elements, some of the issues

overlap,

[19] To obtain an interlocutory injunction, Corus must, at a minimum, demonstrate with respect

to any or all of its claims:

(1) that there is a serious question to be tried, in the sense that its claims are not

frivolous or vexatious;

(2) that it will suffer irreparable harm if the interlocutory injunction is refused;

and

(3) that the balance of convenience favours granting the injunction, meaning that

Corus would suffer greater harm pending a decision on the merits if the injunction

is not granted than Harvard would suffer if the injunction is granted.

Rv Canadian Broadcasting Corp., 2018 SCC 5 at para 12 citing RIR-

Macdonald v Canada, [1994] | SCR 311.

[20] Corus says that the three requirements for an injunction must not be viewed as a rigid

prescription. Instead it urges me to take a wholistic view to ensure the result reflects the justice

and equity of the situation: Mosaic Potash Esterhazy Limited Partnership v Potash

Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc., 2011 SKCA 120 at para 26. It directs me to Justice Sharpe,

writing extrajudicially, in Injunctions and Specific Performance, (Aurora, ON: Canada Law

Book, 1992) (loose-leaf updated 2019, release 27) at §2.600:

Page: 5

‘The terms “irreparable harm”, “status quo” and “balance of convenience” do not

have a precise meaning. They are more properly seen as guides which take colour

and definition in the circumstances of each case. More importantly, they ought not

to be seen as separate, water-tight categories. These factors relate to each other,

and strength on one part of the test ought to be permitted to compensate for

‘weakness on another.

(21] Despite the fact that an analysis of Corus’ application proceeds through the tripartite test

as if'a series of stages, I agree that the three requirements for an injunction are to be considered

as a whole when assessing their overall impact. The relative strength or weakness in one stage of

the test may be offset by the relative weakness or strength in another.

IV. The Nature of the Injunction

(22] Corus’ seeks a prohibitive injunction to stop Harvard from continuing its allegedly

unlawful conduct. Harvard argues that Corus’ application amounts to a mandatory injunction

because if Corus is successful at this early stage, Harvard will be required to rebrand its station

and replace its digital and non-digital signage, logo, promotions, marketing and on-air messaging

on which it spent approximately $275,000 when it launched POWER 107. Harvard’s National

Program Manager Mr. Christian Hall states in his affidavit that Harvard would also suffer loss of

reputation relating to its business and the 107.1 station generally in a yet undetermined amount.

[23] Asa general principle, where an injunction goes beyond requiring a party to cease acting

and instead compels a party to act, the applicant must meet a higher threshold under the first branch

of the RJR-Macdonald test. Rather than demonstrate that there is a serious issue to be tried, it

must establish a strong prima facie case of entitlement, meaning a “strong likelihood on the law

and the evidence presented that, at trial, the applicant will be ultimately successful in proving the

allegations set out in the originating notice”: Canadian Broadcasting Corp. at para 15 and 17.

This distinction arises from the fact that the defendant may face potentially severe consequences

and would be required to take concrete positive steps should a mandatory injunction be granted.

[24] The Supreme Court in Canadian Broadcasting Corp. discusses not just the challenge of

distinguishing between a prohibitive injunction and a mandatory injunction, but also the fact that

prohibitive injunctions often carry with them burdensome costs to compliance. It cites with

approval the decision in Mosaic Potash where the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal observed that

the substantive differences between the impact of mandatory and prohibitory injunctions can be

easily overstated, Ultimately, the Supreme Court in Canadian Broadcasting Corp. at para 16 and

says that my respon ty is to examine the overall effect of the injunction,

[25] Notwithstanding that Harvard may have to take significant and tangible steps to comply

with an interlocutory injunction, if granted, I am satisfied that the overall effect of the injunction

sought by Corus is to restrain Harvard from doing something. In these circumstances, Harvard's

burden to comply does not alter my view that Corus is seeking a prohibitive injunction. The burden

on Harvard of complying with an interlocutory injunetion is properly a factor to be considered in

assessing the balance of convenience.

[26] Inaddition, Harvard’s evidence is that it kept the rebranding of its 107.1 station to POWEI

107 secret not just from the public and its competitors, but from most of its employees. To avoid

Page: 6

any leak, it was careful to not take any steps that would signal the rebrand until after the August

2019 launch. Harvard investigated whether it could use the POWER name, was aware of

Corus* registered trademarks, and knew Corus’ history of operating the POWER 92 station and its

other POWER stations. Harvard wanted the element of surprise with its launch. As a consequence,

Corus had no notice of Harvard’s rebranding and no opportunity to challenge Harvard’s use of the

POWER 107 name, logo, slogan, promotions and on-air messaging prior to Harvard’s launch.

Corus communicated its disapproval of Harvard’s actions on August 21, 2019.

[27] Tam satisfied that the consequence of Harvard's launch strategy should not now visit on

Corus an increased burden when it asks this court to protect its interests. For these reasons, Corus

therefore need only establish that there is a serious issue to be tried,

Analysis

1. Serious Issue to be Tried

28] The first branch of the RJR-Macdonald test requires that I undertake a preliminary

assessment of the strength of Corus’ case to decide whether there is a serious issue to be tried.

There are no specific requirements that must be met to satisfy this test. My evaluation need not

go so far as to determine whether Corus is likely to succeed at trial. Indeed, it would be

premature for me to make any such determination, The question I am to answer is whether

Corus’ action is frivolous: RJR-Macdonald at paras 54-55.

A. Copyright Infringement — Logos and POWER 92 advertising materials

Law

[29] Protection of works under the Copyright Act, RSC 1985, c. C-42 has the dual objective of

promoting the public interest in the encouragement and dissemination of original work and

ensuring that any benefit from or value in the work is retained by the author of the work:

Théberge v Galerie d’Art du Petit Champlain Inc, 2002 SCC 34 at paras 30-31. To achieve that

end, copyright laws place in the hands of the owner of the work the sole right to produce and

reproduce the work, and they protect the owner against the work being copied by others.

[30] For a work to be entitled to copyright protection, it must be an original artistic work. This

‘means that there must be some intellectual effort applied to produce the work: Distrimedie Inc, ¥

Dispill Inc., 2013 FC 1043 at para 319 citing CCH Canadian Ltd. v Law Society of Upper

Canada, 2004 SCC 13 at para 16. In a claim of copyright infringement, the plaintiff must prove

substantial similarity and copying: Ranchman’s Holding Inc v Bull Bustin’ Ine, 2019 ABQB

220 at para 158 citing Hutton v Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1992 ABCA 39.

Argument

[31] Corus asserts that the trademarked Logos are original artistic works and alleges that

Harvard infringed Corus’ copyright by substantially copying the trademarked Logos and by

reproducing POWER 92 advertising materials containing the POWER 92 Logo. To support its

first assertion, Corus points to a comparison of the shape, colour scheme and content of the

POWER 107 logo and the POWER 92 Logo. In addition, Corus points to evidence that

establishes not only Harvard's familiarity with the POWER 92 Logo when it defined the

parameters for the design of the POWER 107 logo, but an acknowledgment by one of Harvard's

affiants, Mr. Cam Cowie Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of Harvard, that there w

Page: 7

at least some intention, although it was not Harvard’s primary intention, to connect POWER 107

to what was familiar from the POWER 92 station, including the Phrase That Pays contest and the

POWER 92 Logo.

[32] With respect to the second assertion, Harvard admits that it re-posted a social media

image that contains the POWER 92 Logo and POWER 92’s promotion of its Phrase that Pays

contest. It also admits that it modified the posting by adding “@powerl07yeg” and “Back this

Monday #PhraseThatPays”.

(33] Harvard says Corus cannot succeed in its application for an injunction based on copyright

infringement for three reasons: first, it says Corus has not proven that itis the owner of the

copyright in the POWER 92 Logo and the print advertisement. In that regard, it says Corus has

not produced sufficient evidence of the chain of ttle linking Corus to the author of the work. It

relies on the court’s comments in Distrimedic Inc. to argue that its failure to do so is fatal to

claim. Second, pointing to the same alleged evidentiary gap, it says that Corus has not provided

proof that the POWER 92 Logo and print advertisement are original works. Third, it says there

are sufficient distinguishing features between the POWER 107 logo and the POWER 92 Logo

such that there is no infringement. It points to the absence of the “FM” broadcasting method in

the POWER 107 logo, the different fonts and font sizes, and the absence of a tagline in the

POWER 107 logo as compared to the POWER 92 Logo.

Discussion

[34] The question before me is whether Corus can rightfully assert copyright in the

trademarked Logos and the POWER 92 advertising materials as the owner of the original work.

The issue is whether based on the evidence it has presented, Corus’ claim to ownership in an

original work is so doubtful that it does not deserve consideration by the trier of fact at a future

trial: Milano Pizza Ltd. v. 6034799 Canada Inc., 2018 FC 1112 at para 152.

[35] Both under the Copyright Act and at common law, the author of a work is the owner of

the copyright in the work: Copyright Act section 13(1). For Corus to own the copyright, either

the original author must have been an employee of WIC, or WIC must have been assigned

ownership in the work by the original author. Section 34.1(b) of the Copyright Act provides that

in any civil proceedings taken under the Copyright Act in which the defendant puts in issue the

plaintiff's claim to the copyright, the author of the work shall be presumed to be the owner of the

copyright unless otherwise proved,

[36] The evidence I have is that Corus acquired WIC’s radio broadcasting business as an

operating business. While the Master Agreement forming part of the WIC Transaction does not

specify all of the intellectual property acquired by Corus, in the absence of evidence to the

contrary it is reasonable to conclude that the sale of the operating business included all of the

authorities needed to operate that business, including the authorities relating to intellectual

property. That expectation is reinforced by the uncontroverted evidence both from the trademark

registry and Mr. Phillip’s evidence that the POWER 92 Logo was in use as early as 1991 in

respect of the operation and promotion of a radio station.

[37] In the Distrimedic Inc. case, there was a direct contest between the plaintiff by

counterclaim and the defendant by counterclaim regarding who created the alleged work. The

plaintiff by counterclaim produced documents respecting certain corporate transactions that it

argued demonstrated a transfer of the copyright, but it did not call the person it claimed to be the

Page: 8

author of the alleged work despite that person’s availability to testify. The court drew an adverse

inference against the plaintiff by counterclaim for failing to do so. In the case before me, no

party asserts a contrary claim of ownership, although I note that is not required under section

34.1(1)(b).

[38] Despite the fact that Corus has not presented definitive evidence that the author of the

‘work was a WIC employee or was WIC’s agent who assigned his/her work to WIC, I am

satisfied given the transaction history and Corus’ use of the POWER 92 Logo since as early as

1991 that there is a serious issue to be tried regarding Harvard’ alleged infringement of Corus”

copyright over the POWER 92 Logo.

[39] With respect to Harvard’s argument that there is no evidence that the POWER 92 Logo

was an original work, Harvard’s position in that regard conflicts with its own actions regarding

the development of the POWER 107 logo. In Mr. Hall’s cross examination on his affidavit, he

was asked to describe the process by which the POWER 107 logo was designed. His evidence

was that Harvard commissioned a graphic artist who produced a number of alternatives within

certain parameters identified by Harvard but that he was also given the “free-for-all” to do

whatever he wanted. In other words, he was expected to use some creative effort.

[40] Inmy view, particularly in light of Harvard’s own evidence as to how the POWER 107

logo was designed, it would be a presumptuous and imprudent conclusion that the POWER 92

Logo was not an original work or that its creation did not require more than trivial skill and

judgment. Corus need not put forward the author of the work for this Court to recognize that the

‘graphic art form itself requires creative effort.

{41] _ Finally, with respect to Harvard’s argument that the POWER 92 Logo is not sufficiently

distinct to support a claim of copyright, Harvard argues that where an idea can only be expressed

ina limited number of ways or is sufficiently general, itis not entitled to protection, Symbols

that are simple or whose content is simple may be entitled to copyright. There are many modern

Jogos where the simplicity of the logo is a distinguishing feature. Moreover, Mr. Hall was aware

that radio stations trademark their name and logo. He researched those trademarks in deciding on

the POWER name and the POWER 107 logo.

[42] One factor that may be regarded in determining whether a particular work is substantially

similar to another work is whether the respondent intentionally appropriated the applicant’s work

to save time and effort and whether the work is used in the same or similar fashion as the

applicant's work: Warman v Fournier, 2012 FC 803 at para 23 citing U & R Tax Services Ltd v

HE&R Block Canada Inc, (1995] FCJ No 962. Mr. Hall testified that he looked at the POWER 92

Logo as well as other design marked logos in the radio space when Harvard planned its rebrand

of the 107.1 station. In addition, Mr. Hall’s evidence was that Harvard saw value in using a name

already associated with a pop music station. The existence of this evidence supports my

conclusion that there is a serious issue to be tried with respect to Corus’ copyright claim.

[43] _ Based on the evidence presented and the law regarding copyright, I am satisfied that

Corus’ claims of copyright infringement present a serious issue to be tried, both as to the

imilarity of the POWER 92 Logo with Harvard’s POWER 107 logo, and Harvard’s re-posting

of a POWER 92 advertisement that contains the POWER 92 Logo.

Page: 9

B. Trademark Infringement — Trademarked Logos and POWER 97

Law

[44] A registered trademark gives the owner of the trademark exclusive right to its use, and

entitles that owner to protection against its misuse. That exclusive use is infringed where any

person sells, distributes, or advertises any goods or services in association with a confusing

trademark or tradename: Trademarks Act, RSC 1985, c. T-13, section 20(1){a). For this cause of

action, the issue is whether there is a serious question as to confusion between the trademarked

Logos and POWER 97 word mark, and Harvard’s POWER 107 name and logo.

Argument

[45] Corus says Harvard's POWER 107 logo is easily confused with its trademarked Logos

within the meaning of sections 6 and 20 of the Trademarks Act. It says the confusion is not only

apparent when the logos are compared side by side, but is evident in public response recorded in

social media content appended as exhibits to the affidavit of Brad Phillips, the Vice President

and Head of FM Radio for Corus.

[46] With respect to its word mark in POWER 97 used by its Winnipeg station, Corus says it

is entitled to national protection of that word mark. Despite not having direct evidence of

confusion between the POWER 97 word mark and Harvard’s use of the name POWER 107, it

says that if there is confusion in the listening public between POWER 92 and POWER 107,

which it says there is based on social media evidence, there must be the potential for confusion

between the POWER 97 word mark and Harvard’s POWER 107 given their greater similarity,

[47] Finally, Corus argues that its marks, including its POWER 92 Logo, are entitled to

heightened protection as they form a “family” of marks. The more marks there are that contain

common distinctive elements, the more likely it is that someone will assume a similar mark is.

associated with that family: Kelly Gill & R Scottie Jolliffe, Fox on the Law of Trademarks and

Unfair Competition, 4" ed (Toronto: Carswell, 2002), section 8.7(h)..

[48] _ Harvard challenges the validity of the trademarked Logos that Corus seeks to protect. It

does so in this application and it has done so under section 45 of the Trademarks Act by

requesting that the Registrar of Trademarks provide notice requiring Corus to furnish evidence of

use of the trademarked Logos. As our trademark laws in Canada are a use it or lose it scheme,

Harvard says that Corus’ lack of use of the trademarked Logos is tantamount to abandonment,

Harvard points to the evidence from Mr. Phillips at his cross examination that to his knowledge,

Corus has not used the trademarked Logos since 2003 or 2004. It says Corus cannot claim

protection of the trademarked Logos as it has abandoned those trademarked Logos.

[49] Even if Corus can maintain its trademarks, Harvard argues the trademarked Logos are not

distinct and therefore do not warrant protection, or they do not sufficiently resemble the POWER

107 logo to possibly give rise to confusion, Harvard says there is either no evidence or

insufficient evidence before me to find that there is a serious issue to be tried with respect to

Corus’ claim of trademark infringement

he law is clear that a trademark registrant cannot maintain a mark simply to let it hide,

and only spring it out when a competitor tries to enter the market with a similar mark: Jose

Cuervo SA de CV v Bacardi & Company Limited 2009 FC 116 at para 44. It is also clear that a

Page: 10

‘mere intention to resume use of a mark in the future may not excuse a holder's non-use of it;

Scott Paper Ltd v Smart & Biggar, 2008 FCA 129 at para 28. However, it is also clear that the

abandonment of a trademark requires evidence of intention to abandon and not just lack of use:

White Consolidated Industries, Inc. v Beam of Canada Inc., [1991] FCJ 1076 at para 48.

[51] The question I am to determine at this interlocutory stage is whether there is a serious

issue to be tried regarding Corus” claim for trademark infringement. The threshold to establish a

serious issue to be tried is low and I am not to make what would amount to a final determination

on the validity of the trademarks.

[52] Mr. Phillips has been employed by Corus since 2012. The evidence I have from him is

that he has made inquiries and understands that Corus is not aware of instances of use of the

POWER 92 Logo since 2004. His evidence is also that Corus has and continues to consider a

revival of the POWER brand in Edmonton, While Harvard asks that I discount Mr. Phillips?

evidence on this point because it is not supported by any meeting note or confirming record, I

hhave no reason to reject Mr. Phillips’ evidence. This litigation itself indicates the extent to which

Corus will go to protect wiat it believes it owns and what it valu

[53] Corus’ trademarks are registered. Whether those trademarks are validly claimed is not for

‘me to decide at this preliminary stage, particularly on an evidentiary record that establishes, at

least at face value, no intention to abandon. More evidence is required to determine the issue of

abandonment, Further, Harvard acknowledges in its written materials that there is competing

evidence and competing arguments regarding the distinctiveness of the POWER 107 and

POWER 92 logos, considering their shape, colour scheme, and content. The issue of

distinctiveness is a live dispute.

[54] Based on the evidence presented and considering the law regarding trademark

infringement, I am satisfied that Corus has demonstrated that there is a serious issue to be tried

with respect fo whether itis entitled to protection of its trademarks.

C. Passing Off

Law

[55] Whereas the Trademarks Act creates a right to claim infringement with respect to

registered trademarks, the tort of passing off is the equivalent cause of action for the

infringement of unregistered trademarks: Kirkbi AG v Ritvik Holdings Inc, 2005 SCC 65 at para

25. In Kirkbi at para 23, the Supreme Court confirmed that section 7(b) of the Trademarks Act

essentially codifies the common law tort of passing off:

7 No person shall

L.

(b) direct public attention to his goods, services or business in such a way as to

cause or be likely to cause confusion in Canada, at the time he commenced so to

direct attention to them, between his goods, services or business and the goods,

services or business of another;

[56] At common law, the right to a trademark arose through the use of a mark by a business to

identify its products to the public. The doctrine of passing off did not develop to protect

monopolies in respect of products, but to protect the guises, get-ups, names, and symbols that

distinctively identify the maker: Kirkbi at para 67. “Get up” might be simply one’s brand name,

Page: 11

trade description or the individual features of packaging if recognized by the public as

distinctive: Ciba-Geigy Canada Ltd. v Apotex Inc., [1992] 3 SCR 120 at page 132. The

overarching policy concern addressed by the tort of passing off is honesty and faimess of

competition: Kirkbi at para 63.

[57] The three components of a passing off action, whether at common law or under section

7(b) of the Trademarks Act are: first, the existence of goodwill in the distinctiveness of the

product, meaning the guise, get-ups, names and symbols that identify the distinctiveness of the

source; second, the misrepresentation of the public, whether or not wilful, causing or likely to

cause confusion; and third, actual or potential damage to the plaintiff: Kirkbi at paras 67-68.

Argument

[58] Corus suggests that the value in POWER 92's goodwill is evident in the language chosen

by Harvard to promote its POWER 107 station, by the social media posts Harvard has created,

by public comment that Harvard has “liked” “re-tweeted” or “re-posted”, and by the evidence of

Harvard’s employees that acknowledges the connection between POWER 92 and POWER 107.

It says the result of Harvard’s actions is that listeners to Harvard's POWER 107 station infer that

POWER 107 is a revival of, continuation of, or is somehow associated with Corus’ POWER 92

station. They say that every distinct element of Corus” POWER 92 radio brand, including its

name, logo, slogan, listener contests and music playlist, has been replicated or mimicked by

POWER 107 to Corus’ detriment.

[59] Harvard’s response is to deny all elements of the tort of passing off. It denies that Corus

holds goodwill in the POWER 92 get-up either because itis not proved, not distinct, or has not

been preserved by use. It denies that there is the possibility of confusion between POWER 92

and POWER 107 and says Corus has not produced sufficient evidence of confusion. It denies

that Corus has suffered any actual or potential damage.

Discussion

[60] A material portion of the parties’ submissions on the tort of passing off were made in the

context of assessing irreparable harm — the presence of goodwill, the sufficiency of the evidence

regarding listener confusion, the causal link between confusion and loss of goodwill, and

whether Corus has provided adequate evidence of irreparable harm, There was little or no

argument that there is a serious issue to be tried with respect to this aspect of Corus’ claim.

[61] _ My obligation at this stage is to determine whether, on a limited review of the evidence,

there is a serious issue to be tried that Harvard’s launch of its POWER 107 has damaged

goodwill that Corus claims in its POWER 92 brand. For the reasons discussed under my analys

of Corus’ claim for irreparable harm, I am satisfied that Corus’ claim of passing off presents a

serious issue to be tried.

D. False or Misleading Representations under the Competition Act

Law

[62] Section 52 of the Competition Act, RSC 1985, ¢ C-34 says:

52 (1) No person shall, for the purpose of promoting, directly or indirectly, the

supply or use of a product or for the purpose of promoting, directly or indirectly,

any business interest, by any means whatever, knowingly or recklessly make a

representation to the public that is false or misleading in a material respect.

Page: 12

[63] By virtue of section 36 of the Competition Act, any person who has suffered loss or

damage as a result of conduct that is contrary to section 52 (and other provisions) of the

Copyright Act, may sue the person who engaged in the unlawful conduct to recover its loss or

damage. Section 36 creates a private cause of action outside of the otherwise quasi-criminal

scope of offences set out in the Competition Act. That private cause of action provides that Corus

is entitled to damages in the event it proves that Harvard engaged in false or misleading

advertising. The statute establishes a right to bring proceedings to recover proven losses.

{64] A determination under section 52 of the Competition Act includes consideration of the

general impression and the literal meaning of the advertisement, and whether the advertising is

misleading in a material respect.

Argument

[65] Corus alleges that Harvard has engaged in false and misleading advertising contrary to

section 52 of the Competition Act. It says that by Harvard’s choice of language in its promotions

that is backwards focused, like “familiar”, “back on” and “return”, Harvard created the

misleading impression that POWER 107 is a revival of, a continuation of, or is associated with

Corus. Corus say’ that the question of whether Harvard made representations to the public that,

are false or misleading is a serious issue to be tried.

{66] _ Harvard says that the promotional materials complained of that contain backwards

looking language do not refer directly to POWER 92 and in any event harken to the music being

played and not to the POWER 92 station, It says the social media comments that it has “liked”

“re-tweeted” or “re-posted” do not demonstrate that the public is misled in any material respect.

Not only that, Harvard says it has taken steps to ensure that its promotional material and on-air

broadeasts ensure that POWER 107 is identified as a Harvard station,

Discussion

[67] Neither party provided case law as to whether this court has the jurisdiction to grant an

interlocutory injunction where the Competition Act defines Corus’ remedy as the recovery of

damages. In Telus Communications Co v Rogers Communications Inc, 2009 BCCA 581, the

British Columbia Court of Appeal confirmed that while section 36 of the Competition Act

provides a statutory cause of action sounding in damages, its superior court has jurisdiction to

grant an interlocutory injunction given its inherent jurisdiction under section 39(1) of the Law

and Equity Act, RSBC 1996, ¢ 253. Section 39(1) of the Law and Equity Act is akin to section

13(2) of the Judicature Act, RSA 2000, c. J-12. Following the reasor in Telus

Communications, | accept that I have jurisdiction to grant an injunetion where the underlying

claim falls under the Competition Act.

[68] _ However, I am very mindful of the implications of any preliminary determination I may

make relating to this aspect of Corus’ claim given the seriousness of the allegations. A claim

under the Competition Act has a materiality threshold — the representation must be false or

misleading in a material respect. Advertisers that push the bounds of what is fair may not be

misleading in a material respect. In addition, in the civil context, while the burden of proof on the

plaintiff is still proof on a balance of probabilities, itis a heavier burden because of the

seriousness of the allegations. There must be “substantial proof” of activity which is a “very

serious public crime”: Distrimedic Inc. at para 262.

Page: 13

[69] 1 did not receive adequate submissions to determine on a preliminary assessment of the

evidence that there is a serious issue to be tried that Harvard's alleged representations are false or

misleading in a material respect. Corus’ claim for injunctive relief on the basis of its claim of

false or misleading advertising under the Competition Act cannot succeed.

2. Irveparable Harm

[70] Having reached the second branch of the injunction analysis on Corus’ claims for

copyright infringement, trademark inftingement and common law passing off, Corus must

establish on a balance of probabilities that it will suffer irreparable harm if the injunction is not

granted, meaning it must prove that damages after trial would be an inadequate remedy: RJR-

Macdonald at para 64. Whether the applicant is likely to experience irreparable harm is a factual

assessment based on the evidence: Sleep Country Canada Inc v Sears Canada Inc, 2017 FC

148 at para.118. Examples of imeparable harm include permanent market loss or irrevocable

damage to one’s business reputation: RJR-Macdonald at 31. Irreparable harm refers to the

nature of the harm rather than its magnitude: RJR-Macdonald at para 64.

ingement, passing off and copyright infringement in the form of loss of ratings of

its CHUCK 92.5 station and the erosion of its opportunity to re-enter the Edmonton radio market

using its POWER brand.

[72] The parties are widely diverged with respect to the standard of proof Corus is required to

meet and the nature and quality of the evidence it must present to support its claim of irreparable

harm.

A. Standard of Proof

[73] Corus relies on the decision in Mosaic Potash to argue that it should only be required to

prove that there is a meaningful risk of irreparable harm with respect to its claims. In Mosaic

Potash, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal found that to require a high standard of proof of

irreparable harm would place an undue burden on the applicant at the second stage of the

injunction analysis and would render the balance of convenience analysis futile. In further

support of its position, Corus points to Injunctions and Specific Performance at §2.418, where it

says “[iJrreparable harm and the assessment of the balance of convenience are very closely

linked, in some cases where the balance of convenience strongly favours an injunction,

conclusive proof of irreparable harm may not be required.”

[74] Harvard argues that for Corus to succeed on its application for an interlocutory

injunction it must present clear and not speculative evidence. It relies on Syntex v Novopharm

Ltd (1991), FCS No 424 (FCA) and the subsequent cases of Centre Ice Ltd v National Hockey

League, {1994] FCI No 68 (FC) and Sleep Country Canada Inc v Sears Canada Inc, 2017 FC

148 to support its position. Harvard maintains that with respect to trademark infringement and

passing off, Corus must prove with clear and non-specuilative evidence i) the presence of

goodwill, ii) listener confusion that results in a loss of goodwill; and iii) irreparable harm. It says

a loss of goodwill does not automatically establish irreparable harm, It says that Corus has not

presented clear and not speculative evidence to establish these necessary links in the chain.

[75] The cases on which Harvard relies arise in the intellectual property context and therefore

are instructive given the issues I am asked to consider. In addition, the Alberta Court of Appeal

has recently articulated that irreparable harm must be shown on clear and not speculative

Page: 14

evidence in two cases falling outside of the intellectual property context: EnCharis Community

Housing and Service v Alberta Securities Commission, 2019 ABCA 177 at para 23 citing

Modry v Alberta Health Services, 2015 ABCA 265 at para 82. I am satisfied that Corus is

required to show irreparable harm on a balance of probabilities and with clear and not

speculative evidence.

B, Loss of Ratings by CHUCK 92.5,

[76] _ Thave two issues with Corus’ claim that the ratings of CHUCK 92.5 have been harmed

by the launch of POWER 107 and that the resulting loss is immeasurable. First, Corus has not,

demonstrated that the alleged trademark infringement of its trademarked Logos and word mark,

the alleged infringement of its claimed copyright in the POWER 92 Logo, or the allegations of

passing off relating to the POWER 92 get-up are adequately connected to the performance of

CHUCK 92.5. Second, even if they are connected, | am not satisfied that Corus has presented

sufficient reliable evidence that CHUCK 92.5°s ratings have declined as a result of Harvard's

launch of POWER 107.

[77] The competition in the radio industry in Edmonton has more than doubled since both

Corus and Harvard entered the Edmonton radio market, There are now more than 12 FM stations

operating in Edmonton. Both Corus and Harvard agree that to attract listeners, radio stations rely

on the quality and familiarity of their frequency, their music format, the station’s image

(including name, logo and on-air personalities), and its marketing and promotions, although they

place different importance on certain of these features.

[78] Both parties presented a significant amount of data with respect to whether there has been

a measurable impact on CHUCK 92.5’s ratings as a result of Harvard’s launch of POWER 107.

In the radio industry, the non-profit ratings company Numeris PPM Data Edmonton CTRL

provides broadcast measurement and consumer behaviour data to Canadian broadcasters,

advertisers and agencies. Although some data is provided daily, both the broadcasters and the

advertisers review quarterly data to make their decisions. The broadcasters use quarterly data to

assess a station’s performance; and advertisers use the quarterly data to decide where to place

their advertising dollars. POWER 107 was launched with less than a week remaining in the

summer quarter of 2019, As a result, its impact is not detectable in the summer quarterly report.

What Corus produced to demonstrate CHUCK 92.5's alleged loss of ratings since POWER 92's

Jaunch was approximately 5 weeks of data from the fall quarter that neither the broadcaster nor

the advertisers would actually use to make any decision. The quarterly data that will reflect the

relative performance of CHUCK 92.5 and POWER 107 is not yet available and will not be

available until late November 2019,

[79] _ In addition, Corus confirmed that it has no written reports that confirm listener migration,

from CHUCK 92.5 to POWER 107, no year over year revenue comparisons, and no evidence of

lost advertising revenue from CHUCK 92.5 to POWER 107.

{80} _ Further, some of the evidence regarding the performance of CHUCK 92.5 shows that

there has been no appreciable change in CHUCK 92.5’s rankings from August 2018 when

CHUCK 92.5 was launched to August 2019 when POWER 107 was launched. In addition, there

are a number of features of the CHUCK 92.5 station that are distinct from POWER 107,

including music format (artists and year of song) and the fact that CHUCK 92.5 has no on-air

personalities. Corus acknowledged that these features can influence station ratings. Finally,

Page: 15

Corus acknowledged that it had concerns about CHUCK 92.5’s ratings even prior to the POWER

107 launch.

{81] The result of all of this evidence is that Corus has not demonstrated with clear and

reliable evidence either that there has been a negative impact on the ratings and rankings of

CHUCK 92.5 since Harvard’s POWER 107 launch or that there is a connection between

Harvard’s POWER 107 station and the performance of CHUCK 92.5. Corus has not

demonstrated that it will suffer irreparable harm in the form of loss to CHUCK 92.5 as a result of

Harvard's launch of POWER 107. It cannot make out a claim for an interlocutory injunction on

this basis.

C. Loss of Opportunity to Re-Enter the Market as POWER 92

[82] _ Corus claims it has suffered a loss of goodwill and a depreciation in the distinctiveness of

its POWER brand as a result of Harvard's launch of the POWER 107 station. It says its loss is

impossible to quantify and is therefore irreparable. The assessment of irreparable harm in the

context of the passing off claim and the alleged trademark infringement requires that I undertake

an analysis of Corus’ claim of goodwill, confusion or loss of distinctiveness, and harm.

Goodwill

[83] In Ciba-Geigy, Gonthier, J. described goodwill as “a term which must be understood in a

very broad sense, taking in not only people who are customers but also the reputation and

drawing power of a given business in its market”. He went on to cite from Salmond on the Law

of Torts (17" ed. 1977) that “the true basis of the [passing off] action is that the passing off

injures the right of the property in the plaintiff, that right of property being his right to the

goodwill of his business” (emphasis in original text). Goodwill is part of the value of the

business and is part of what a party owns: Ciba-Geigy at page 134 citing Consumers

Distributing Co v Seiko Time Canada Ltd, [1984] 1 SCR 583.

[84] In Asbjorn Horgard A/S v Gibbs/Nortac Industries Ltd., 1987 FCA at para 27, the court

referred to goodwill as “the benefit and advantage of the good name, reputation and connection

of'a business, the attractive force which brings in custom, and the one thing which distinguishes

and old-established business from a new business at its first start.” This pays regard to the fact

that the potential to build goodwill is connected to the period of time in which the business has

served its customers. That same concept is reflected in Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Boutiques

Cliquot Ltée, 2006 SCC 23 at para 52 where the court describes goodwill as the benefit that

follows from reputation and connection.

[85] _ ‘The material date for assessing Corus’ claim of goodwill is August 2019, when Harvard

launched its POWER 107 station: see Sandhu Singh Hamdard Trust v Navsun Holdings Ltd,

2018 FC 1039 at para 30.

[86] In Veuve Clicquot, the Supreme Court set out considerations for determining goodwill in

reference to section 22 of the Trademarks Act. In Sandhu Singh at para 35, the Federal Court

found those same considerations were appropriate factors to determine the existence of goodwill

in a claim for passing off. Those factors are:

...degree of recognition of the mark within the relevant universe of consumers,

the volume of sales and the depth of market penetration of products associated

with the claimant's mark, the extent and duration of advertising and publicity

accorded the claimant's mark, the geographic reach of the claimant's mark, its

Page: 16

degree of inherent or acquired distinctiveness, whether products associated with

the claimant's mark are confined to a narrow or specialized channel of trade, or

move in multiple channels, and the extent to which the mark is identified with a

particular quality...

Veuve Clicquot at para 56

87] In my view, all of this is common sense. Goodwill arises by how a company does its

business and the ways in which it distinguishes its service; it builds over the period of time in

which people enjoy and recognize what it produces; and that goodwill does not evaporate when

the business is retired.

[88] _ Mr. Hall testified that when Harvard chose the POWER name for its 107 station, it

assumed that listeners from the ‘90s and 2000s who enjoyed pop music in Edmonton would

likely remember a radio station named POWER. In a podcast discussing the launch of the

POWER 107 station, a Harvard employee says “...with the heritage of the Power name...we see it

as a great opportunity.” That sentiment is repeated in social media posts from both Harvard

employees and members of the public that Harvard “likes” “re-tweets” or “re-posts” including:

“Thaven’t been this happy listening to a radio station since back in the Power 92

days!

“The new Power 92, for us old kids.”

“are you guys going out of your way to play songs that I vividly remember

playing on my beloved Power92?”

mean...

“Power 92 plays today’s best music, now show me my money!

[89] Harvard's on-air announcer says “POWER is something that is legendary in Edmonton. I

‘grew up listening to a station that had POWER in the title and our logo kind of reminds me of

it.” She makes similar comments in a social media post: “I grew up listening to a station called

Power in this exact city. I’m talking every single day, as often as possible. Whenever T had a

radio nearby, it was on. Loud. I can’t believe Iam now the morning show host of Power. If you

grew up in this city, you probably have vivid memories of listening to their morning show or

station in general.”

[90] _In my view, this evidence is sufficient to establish that POWER 92 was popular, was

recognized, was enjoyed by its listeners and is remembered for its logo, its slogan, its contest, its

on air personalities and its music. I am satisfied that Corus has demonstrated that it holds current

goodwill in its POWER 92 brand and that the existence of that current goodwill has been

established by clear and not speculative evidence.

(91] The residual value of the POWER name, slogan and Phrase that Pays contest is evident in

the language chosen by Harvard to promote the POWER 107 station, It is evident from the social

media posts Harvard produced and those public posts that it “liked” “tweeted” or “re-posted”;

and it is apparent from the evidence from Harvard’s own employees that acknowledge the

connection between POWER 92 and POWER 107 and the legacy of the POWER 92 station in

Edmonton, It is not necessary for Corus to present a survey of listeners to demonstrate the

goodwill it has generated and that still resides in the POWER brand. The listener response that

was “liked” “tweeted” or “re-posted” by Harvard, only some of which I have captured, is

sufficient evidence of public response.

Page: 17

[92] 1am also satisfied that Corus’ POWER 92 brand or get-up not only has current value, but

that Corus relied on that value in 2019, The evidence from Mr. Phillips is that in the summer of

2019 and before Corus had any awareness of the POWER 107 launch, Corus created three

promotions that reference POWER 92, its name or its Phrase that Pays contest. Corus has proved

with clear and not speculative evidence that there is enduring value in the “advantage 0

reputation” and that this reputation and goodwill is property that Corus possesses and that it can

and does use

Confusion or Loss of Distinctiveness

[93] Turning then to the issue of confusion, the question of whether there is a likelihood of

confusion is to be answered in the context of the particular case and from the perspective of the

ordinary hurried purchaser. To establish the tort of passing off, evidence of likelihood of confusion

that may lead to the possibility of lost business opportunity is relevant; however, the Plaintiff is

not required to prove actual confusion: Vancouver Community College v Vancouver Career

College, 2017 BCCA 41 at para 30, As set out in Veuve Clicquot, the test is whether, as a matter

of first impression, the “casual consumer somewhat in a hurry” who encounters POWER 107, with

no more than an imperfect recollection of POWER 92's get-up, would be likely to think that

POWER 107 was the same source of radio services as POWER 92 or was associated with POWER

ee

[94] In Steep Country, a case upon which Harvard relies, the Federal Court said at para 87-88:

Sears asks the Court to draw an inference from the lack of actual evidence of

confusion; however, no such inference is warranted. The Court ean assess the

likelihood of confusion in the absence of actual evidence of confusion toa

‘consumer, as noted by Justice Manson in Black & Decker at para 75-79. As noted

by Professor Wong, a methodologically sound consumer survey would not have

been possible within the time period preceding this motion and, in his view, was

not necessary.

Moreover, the jurisprudence has established that in circumstances like the present,

the Court is as well placed as an expert to determine whether confusion will occur

(Masterpiece, at paras 75- 101). In the present case, although the experts opine on

confusion, the Court is equally capable of making this determination. (emphasis

added)

[95] Taking guidance from the Trademarks Act, confusion can be established by considering

the inherent distinctiveness of (in this case) the POWER 92 brand, looking at how long that brand

was in use, how the brand (including the name, logo, slogan and listener contest) was used and the

extent to which it resembles not just in appearance but in idea Harvard’s POWER 107 station. A

loss of distinctiveness from another person’ s use of a similar brand will damage goodwill: Reckitt

Benckiser LLC v Jamieson Laboratories Ltd, 20\5 FC 215 at para 55, affd 2015 FCA 104,

Notably, the evidence of confusion in Reckitt was two Facebook comments from consumers, one

product display where a store displayed the plaintiff's products as that of the defendant, and the

results of entering the plaintiff's brand name into a search engine, That evidence was considered

clear and not speculative and sufficient to find confusion,

[96] _ In addition to the comments from Harvard employees and listeners mentioned above, I

consider the following evidence. First, in reposting public comments referencing the Phrase that

Page: 18

contest, POWER 107 posted: “Even mentioning #POWER107Edmonton has been giving

you ideas... ‘The radio contest that was famous NATIONWIDE, and the station that gave it to

you” (emphasis added). Mr. Hall confirmed in his cross examination that HOT 107 never ran the

Phrase that Pays contest. That notwithstanding, POWER 107 suggests to its listeners that itis the

station that “gave” listeners the contest. In other promotions, Harvard says “The retum of the

#PhraseThatPays”. Moreover, it re-posted and commented on a POWER 92 advertisement that,

contained the POWER 92 Logo and the Phrase that Pays contest in an effort to promote its own

station and contest.

[97] | When asked whether a POWER 107 promotion that reads “Turn the POWER back on”

was a reference to POWER 92, Mr. Hall’s answer was “In a cute way, yes.” Mr. Hall’s evidence

‘was also that listener familiarity with POWER 92 was one reason, although not the primary

reason, for naming Harvard’s radio station POWER 107. When Mr. Cowie was presented with a

proposition that it was “not a coincidence that a number of the promotional aspects that go with

POWER 107 resemble the promotional aspects that went with the old POWER 92 brand” Mr.

Cowie answered “was it part of it? Sure.”

(98] _ In this case, I have before me clear evidence that listener response to the POWER 107

station is not just to the music it plays, but draws on the association to the POWER 92 brand: the

Phrase that Pays contest, the POWER 92 Logo and the former POWER 92 programming and on-

air announcers. Harvard employees acknowledge the heritage of the POWER name in the

Edmonton radio industry, and Harvard assumed that listeners from the 90s and 2000s would.

likely remember the Corus POWER 92 station. Harvard’s actions have invited the average

listener to associate the goodwill it might hold for POWER 92 with Harvard’s POWER 107

station. | accept that in doing so, Harvard has created confusion and a loss of distinctiveness with

respect to Corus’ POWER 92 brand.

[99] This reasoning encompasses Corus’ claim for trademark infringement, passing off and

the issue of similarity in copyright infringement.

Harm

[100] That then takes me to whether Corus has established irreparable harm,

(101] Corus says that as it has not yet re-entered the Edmonton market using its POWER brand,

it cannot be expected to demonstrate tangible loss with evidence that is clear and not speculative.

Itrefers to the decision in Reckitt to support this proposition.

[102] In Reckitt, the Federal Court of Appeal addressed what evidence of irreparable harm the

plaintiff must provide in a claim for trademark infringement and passing off when the plaintiff

‘was not present in the market at the time the defendant Jamieson entered with its competing

product. Jamieson took the position that the trial judge was bound by Centre Ice and that a

failure by the plaintiff to produce evidence of, for instance, price reductions or lost sales, was

fatal to its claim. Jamieson argued that the trial judge was not in a position to conclude that the

damages claimed by the plaintiff were truly irreparable.

[103] The trial judge found that Reckitt had established that its damages would be impossible to

calculate because it would never have the chance to operate its business in a clear market absent

Jamieson’s entry. He also found that Reckitt would lose goodwill due to a loss of the

distinctiveness of its trademark. On appeal, the court made the following comments at para 28-

29:

Page: 19

Turning to irreparable harm, | do not believe that the Federal Court judge erred in

determining that such harm would befall Reckitt in the absence of the relief

requested. I need only observe that Reckitt’s contention that its potential harm

would be impossible to quantify has not been undermined by Jamieson’s

submissions.

Jamieson’s reliance on Centre ce is misplaced given the facts of this case,

wherein the party seeking to enforce its trade-mark entered the market in question

after the alleged infringer. It of course makes no practical sense to require a

plaintiff to demonstrate such damages as lost sales or price reductions when the

only market environment in which the plaintiff has ever operated has been one in.

which the alleged infringer has operated as well. (emphasis added)

[104] In my view, the same issue arises here. The continued use by Harvard of the POWER 107

name will narrow any remaining opportunity that Corus has to re-enter the market relying on its

goodwill and the reputation on which itis entitled to trade. So long as and for as long as Harvard

is in the market as POWER 107, Corus cannot deploy its asset, being the goodwill it holds in its

brand and reputation. The injury to Corus from Harvard’s actions extends beyond loss of revenue

associated with loss of listenership. The goodwill of the business, the reputation on which it

trades, will be damaged. Further, if Harvard is not enjoined, Corus’ distinctiveness in its

POWER brand will continue to fade. This is a loss not compensable in damages. In such unique

circumstances as this case is, 1 conclude that Corus would suffer irreparable harm if the

injunction is not granted.

3. Balance of Convenience

[105] The third stage of the tripartite injunction test requires an assessment of the balance of

convenience to identify the party that would suffer greater harm from the granting or refusal of

the interlocutory injunction pending a decision on its merits: Canadian Broadcasting Corp. at

para 12. The factors that must be considered in the balance of convenience will vary in each

individual case: RJR-Macdonald at 324. The court is given the discretion to consider a wide

range of factors: Bar C Ranch and Cattle Company Ltd. v Red Rock Sawmills Ltd., 2004

ABCA 113 at para 17.

[106] In undertaking this analysis of the balance of convenience, I have considered and weighed a

number of factors. I have considered the fact that Corus permitted its trademark in POWER 92 to

lapse and that it admits to not having used the POWER 92 Logo since 2004.

[107] I have also considered the cost to Harvard of compliance with an interlocutory injunction.

Those costs are not insignificant. While some of those costs are already known, other costs are not

yet quantified. Although Harvard may incur costs if an injunction is ordered at this interlocutory

stage, Corus has given an undertaking as to damage such that if, after trial, the court determines that

Corus is not entitled to an injunction, Corus will pay those damages that the court determines

Harvard has suffered.

[108] Despite these factors that weigh in favour of denying Corus’ application, Iam satisfied that

the balance of convenience favours granting an interlocutory injunction. In reaching this conclusion,

Thave considered and weighed the fact that Harvard employees involved in the decision to rebrand

the 107.1 station to POWER 107 anticipated that listeners from the 90s and 2000s would remember

POWER 92; they designed the POWER 107 logo fully aware of the appearance of the POWER 92

Page: 20

Logo; and they investigated the trademark registry and weighed the risks associated with using the

POWER name and the POWER 107 logo. Harvard's affiants admitted that Harvard’s promotions of

its POWER 107 station invited listeners to recall the POWER 92 station, including the Phrase that

Pays contest and the winning phrase. Harvard has drawn connections between POWER 92 and

POWER 107 by its promotions, advertising and on-air comments, and by “liking” “re-tweeting” and

“re-posting” the connections drawn by the listening public,

[109] After weighing all of these factors and those discussed throughout these reasons, I conclude

that the balance of convenience weighs in favour of granting an interlocutory injunction,

[110] Asa result, for the reasons articulated, Harvard is restrained from directly or indirectly

using in the radio industry the POWER 107 name or logo, the POWER 97 word mark, the

trademarked Logos, any trademark or trade-name that includes POWER, or any trademark or

trade-name that is similar to the POWER 97 word mark or the trademarked Logos. Harvard is

also restrained from making representations to listeners in print, on-line or on-air that imply in

any way that the 107.1 FM Edmonton radio station is a revival of, a continuation of, or is

somehow associated with or is otherwise endorsed by Corus’ POWER brand.

[111] The parties are invited to provide written submissions on costs by January 10, 2020 if,

they cannot otherwise agree.

Heard on the 8" day of November, 2019.

Dated at the City of Calgary, Alberta this 18" day of November, 2019.

N¢ iit

J.C.Q.BA.

Appearances:

Colin Feasby, Brynne Harding and Nathan White

for the Plaintifts

Ariel Z. Breitman and Jonathan J. Bouchier

for the Defendant

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

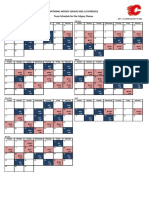

- Calgary Flames 2022-23 ScheduleDocument2 pagesCalgary Flames 2022-23 ScheduleAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Saima Jamal's Letter To Calgary Police, Councillors and Mayor Jyoti GondekDocument2 pagesSaima Jamal's Letter To Calgary Police, Councillors and Mayor Jyoti GondekAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Edmonton Police Association LetterDocument3 pagesEdmonton Police Association LetterCTV News EdmontonNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Aha Letter To Alberta Governement - Jan 13Document2 pagesAha Letter To Alberta Governement - Jan 13Anonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Letter To Calgary PrideDocument2 pagesLetter To Calgary PrideAnonymous NbMQ9Ymq100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- LRT Transit PrioritiesDocument6 pagesLRT Transit PrioritiesAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Edmonton Submission To Province About HomelessnessDocument4 pagesEdmonton Submission To Province About HomelessnessAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Guidance For Professional Sporting TournamentsDocument3 pagesGuidance For Professional Sporting TournamentsAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- ALERT Lays Charges Against 11 People Following Drug-Trafficking InvestigationDocument1 pageALERT Lays Charges Against 11 People Following Drug-Trafficking InvestigationAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Physicians For Alberta HealthcareDocument11 pagesPhysicians For Alberta HealthcareAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- May 13 2020 Gary Bettman NHLDocument2 pagesMay 13 2020 Gary Bettman NHLAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Cease and Desist Letter Sent To Prab GillDocument4 pagesCease and Desist Letter Sent To Prab GillAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Statement of Claim Filed by Family of Tim HagueDocument14 pagesStatement of Claim Filed by Family of Tim HagueAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Obesity Canada InfographicDocument1 pageObesity Canada InfographicAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Final - Notice of Motion - Advocating For Creation of Task Force On Property Tax Assessment ReformDocument2 pagesFinal - Notice of Motion - Advocating For Creation of Task Force On Property Tax Assessment ReformAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Statement of Claim Against Checker Cabs LTD., Hinta Oqubu and John DoeDocument7 pagesStatement of Claim Against Checker Cabs LTD., Hinta Oqubu and John DoeAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Post-Alberta Leaders Debate Ipsos/Global News PollDocument21 pagesPost-Alberta Leaders Debate Ipsos/Global News PollAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Notice of Motion: Immediate Tax Relief For Calgary BusinessesDocument3 pagesNotice of Motion: Immediate Tax Relief For Calgary BusinessesAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Letter Sent To Owners at Hillview Park Condo ComplexDocument3 pagesLetter Sent To Owners at Hillview Park Condo ComplexAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- GovernmentEmailAlbertaPrivacyCommissionerReport2019 PDFDocument101 pagesGovernmentEmailAlbertaPrivacyCommissionerReport2019 PDFAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Court of Appeal Ruling On Northlands Application To Have Lawsuit DismissedDocument6 pagesCourt of Appeal Ruling On Northlands Application To Have Lawsuit DismissedAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- Email Guidelines Developed by Alberta's Privacy CommissionerDocument11 pagesEmail Guidelines Developed by Alberta's Privacy CommissionerAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- GovernmentEmailAlbertaPrivacyCommissionerReport2019 PDFDocument101 pagesGovernmentEmailAlbertaPrivacyCommissionerReport2019 PDFAnonymous NbMQ9YmqNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)