Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Theorizing The Digital Object PDF

Uploaded by

IgruOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Theorizing The Digital Object PDF

Uploaded by

IgruCopyright:

Available Formats

THEORY & REVIEW

THEORIZING THE DIGITAL OBJECT1

Philip Faulkner

Clare College, University of Cambridge,

Cambridge, CB2 1TL, UNITED KINGDOM {pbf1000@cam.ac.uk}

Jochen Runde

Cambridge Judge Business School and Girton College, University of Cambridge,

Cambridge, CB2 1AG, UNITED KINGDOM {j.runde@jbs.cam.ac.uk}

Prompted by perceived shortcomings of prevailing conceptualizations of digital technology in IS, we propose

a theory aimed at capturing both the ontological complexity of digital objects qua objects, and how their iden-

tity and use is bound up with various social associations. We begin with what it is to be an object, the dif-

ferences between material and nonmaterial objects, and various categories of nonmaterial objects including

syntactic objects and bitstrings. Building on these categories we develop a conception of digital objects and

a novel “bearer” theory of how material and nonmaterial objects combine. The role of computation is con-

sidered, and how the identity and system functions of digital objects flow from their social positioning in the

communities in which they arise. Various implications of the theory are identified, focusing on its use as a

conceptual frame through which to view digital phenomena, and its potential to inform existing perspectives

with regard both to how digital technology per se and the relationship between people and digital technology

should be theorized. These implications are illustrated with reference to secondary markets for software, the

treatment of digital resources in the resource-based, knowledge-based, and service-dominant logic views of

organizing, and recent work on sociomateriality.

Keywords: Nonmaterial objects, digital objects, bitstrings, digital technology, social positions, resources,

resource-based view, service-dominant logic, sociomateriality, imbrication

Introduction 1 tegui, 2011; Susarla et al. 2012), 3D printers (Kyriakou et al.

2017), and enterprise systems (Strong and Volkoff 2010;

One of the striking features of the digital revolution has been Sykes 2015).

the proliferation of what we will call digital objects, many of

which have transformed and become indispensable parts of Illuminating as these and similar studies invariably are,

organizational life. Digital objects feature prominently in IS however, their principal focus is on the human and organi-

research and include computer systems and peripherals (Hib- zational implications of the technology in question rather than

beln et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2017), smart devices (Prasopoulou on the devices themselves. The result is that research of this

2017; Yoo 2010), mobile apps (Boudreau 2012; Claussen et kind tends to invoke “pretheoretical understandings” (Ekbia

al. 2013; Hoehle and Venkatesh 2015), emails (Barley et al. 2009, p. 2555) of the entities involved, with the potential lack

2011; Wang et al. 2016), blogs (Aggarwal et al. 2012; Chau of clarity, detail and nuance such understandings often entail.

and Xu 2012; Luo et al. 2017), electronic health records This is not a new observation. Almost 20 years ago, Orli-

(Kohli and Tan 2016), online videos (Kallinikos and Mariá- kowski and Iacono (2001) published a much-cited study

criticizing the IS field for its lack of engagement with its

1 “core subject matter—the information technology (IT) arti-

Suzanne Rivard was the accepting senior editor for this paper. Youngjin

Yoo served as the associate editor. fact” (p. 121). Despite the interest this paper generated,

DOI: 10.25300/MISQ/2019/13136 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 1-XX/December 2019 1

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

various follow-up studies indicate that the situation has The remainder of the paper is devoted to some implications of

changed little in the interim (Akhlaghpour et al. 2013; Ayanso our theory. We begin with its role as a conceptual framework

et al. 2007; Grover and Lyytinen 2015). for future IS research which we illustrate with the emerging

phenomenon of secondary markets for downloaded bitstrings.

The need for a more thorough engagement with digital objects We then consider its potential contribution to theoretical

is all the more acute for the difficult ontological questions that perspectives and debates in IS, highlighting how it might

arise about their structure, mode of being, and other basic augment the conceptions of digital technology associated with

properties. In particular, the intangible, or what we will call the resource-based, knowledge-based, and service-dominant

nonmaterial, nature of many digital objects raises questions logic views, inform discussions between the sociomateriality

about how best to theorize this feature and the properties that and imbrication perspectives regarding how the relationship

flow from it, about how the nonmaterial and the tangible or between people and technology should be theorized, and

material combine, and about how the same nonmaterial thing serve as an illustration of the kind of “blue ocean” theorizing

can exist in many different forms. In addition, there is the advocated by Grover and Lyytinen (2015).

issue that, like other human artifacts, digital objects have

aspects that are community-dependent rather than intrinsic,

especially with respect to being the kind of thing they are, and Conceptualizing Digital Technology

how new kinds emerge and existing kinds become obsolete.

Support for the claim that digital technology is often por-

Our aim in this paper is to propose a theory of digital objects trayed in rather simplistic ways in IS, and for its corollary that

able to do justice to these issues. We begin with a literature the field lacks theories rich enough to do justice to its unique-

review that summarizes the current situation in Information ness and diversity, can be found in many places. We briefly

Systems with respect to the conceptualization of digital tech- review two such sources, beginning with Orlikowski and

nology, first in general terms by focusing on empirical studies Iacono’s (2001) influential empirical study of the depiction of

documenting the lack of engagement with digital objects per the IT artifact in the IS literature and subsequent contributions

se in IS research, and then in more concrete terms by focusing that update and broaden its findings. We then consider some

on specific shortcomings in how digital technology is concep- specific shortcomings of how digital technology is repre-

tualized in the resource-based, knowledge-based, and service- sented in IS, illustrated with reference to recent research

dominant logic views of organizing adopted in parts of IS drawing on the resource-based, knowledge-based, and

research. service-dominant logic views of organizing.

We then present our theory, starting with what an object is in

the abstract, before distinguishing between material and The IT Artifact in IS Research

nonmaterial objects and introducing the important subset of

nonmaterial objects that are syntactic objects. These While perhaps best known for the debates it sparked about the

categories provide the basis for our conceptualization of two identity of the IS field and the place of the IT artifact within

kinds of object at the heart of the digital revolution, the it (King and Lyytinen 2006), the Orlikowski and Iacono

bitstring and the more general category of digital objects. article is first and foremost an appeal for more sophisticated

One of our main theoretical innovations is the concept of theorizing of digital technology. Foreshadowing Ekbia’s

“bearers” of nonmaterial objects—the things a nonmaterial (2009, p. 2555) concerns about pretheoretical understandings,

object may be inscribed on, contained within, or borne Orlikowski and Iacono argue that IS research is over-reliant

by—and we pay particular attention to the capacity of on “commonplace and received notions of technology” (p.

bitstrings to serve as nonmaterial bearers of other nonmaterial 121), a point they illustrate by examining the conceptuali-

objects and the idea that there may exist many layers of such zation of IT artifacts in articles published in Information

bearers. Finally, following some brief observations on the Systems Research during the 1990s.

relationship between digital objects and processes of

computation, we provide an account of the social identity of Orlikowski and Iacono identify 14 distinct approaches to the

digital objects, what they are, so to speak, in the communities IT artifact in the articles in their sample, grouping these into

in which they arise. The guiding idea here is that objects, no the 5 more general views summarized in Table 1.

less than people, occupy social positions that locate them as

components in larger systems, and where such positions are According to Orlikowski and Iacono, the only one of the five

deeply relational, performed, and, crucially, inform the social that is conceptually adequate and able to capture the com-

identity of their occupants. plexity, dynamism, and context dependence of IT artifacts is

2 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Table 1. Orlikowski and Iacono’s Five Views of IT Artifact Conceptualization

Nominal IT artifacts mentioned in name only or not at all.

Emphasis on the instrumental effects of IT artifacts; what they are and how they work regarded as

Tool technical issues and often black-boxed. Artifacts seen as discrete, unchanging, and independent of

social setting.

Emphasis on the computational powers of IT artifacts; their ability to represent, manipulate, store,

Computational

retrieve, and transmit information.

IT artifacts described in terms of one or more (usually quantitative) surrogate measure taken to

Proxy

represent the essential feature(s) of an artifact.

Emphasis on the interactions, and relationships, between IT artifacts and the groups involved in

Ensemble

their construction, implementation and use.

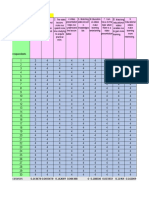

Table 2. Proportion of Articles Employing Each View of Artifact Conceptualization

Orlikowski & Iacono Akhlaghpour et al. Aysano et al. Grover & Lyytinen

2001 2007 2007 2015

Nominal 24.9% 39.6% 17.3% 30.8%

Tool 20.3% 16.0% 28.4% 21.7%

Computational 24.3% 5.8% 6.1% 11.9%

Proxy 18.1% 23.0% 26.6% 24.5%

Ensemble 12.4% 15.7% 21.7% 11.2%

Sample Period 1990-99 2006-09 2000-06 1998-2012

Sample Size 177 644 549 143

MISQ, ISR, JAIS, JIT,

Journals ISR MISQ, ISR, JMIS MISQ, ISR

EJIS, ISJ

Notes: EJIS = European Journal of Information Systems; ISJ = Information Systems Journal; ISR = Information Systems Research; JAIS = Journal

of the Association for Information Systems; JMIS = Journal of MIS; MISQ = MIS Quarterly.

the ensemble view. In all of the other cases, as they see it, the 2007), with the other two studies reporting figures closer to

IT artifact is under-theorized, “either absent, black-boxed, those of Orlikowski and Iacono. Despite evidence of shifts

abstracted from social life, or reduced to surrogate measures” over time within other categories, notably an apparent decline

(p. 130). in the computational view, the overriding impression remains

of a persistent under-theorization of digital technology in IS

The proportion of articles adopting each view found by research. In the meantime, the list of commentaries, opinion

Orlikowski and Iacono appear in Table 2, along with those of pieces, editorials and calls for papers concerned about the

three more recent studies employing the same methodology situation steadily continues to grow (e.g., Baskerville 2012;

(Akhlaghpour et al. 2013; Ayanso et al. 2007; Grover and Benbasat and Zmud 2003; Grover and Lyytinen 2015;

Lyytinen 2015). Zammuto et al. 2007).

Orlikowski and Iacono calculate that only 12.4% of articles While painting a compelling picture of the situation in IS

adopted the ensemble view, the vast majority, therefore, research in general terms, the preceding studies say little

relying on highly attenuated conceptions of digital tech- about specific features of the objects of digital technology

nology. The fact that these results reflect research published that, in a world of seemingly ever-expanding varieties of

over twenty years ago raises the question of whether the digital technology, might warrant theorizing. To appreciate

situation might not have improved in the interim. But the some of these features and achieve a more finely grained

answer appears to be no. Of the three further studies reported picture of the kind of problems our theory aims to address, we

in Table 2, even the highest reported proportion of articles now consider three prominent meta-theoretical perspectives

adopting the ensemble view is only 21.7% (Ayanso et al. in which digital technologies come to the fore.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 3

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Digital Technologies As Resources of IT business value, we contend there is more to be said

about the devices themselves.

The three perspectives we will focus on are the resource-

based (Barney 1991; Barney and Clark 2007; Dierickx and Where devices are discussed explicitly in the three views,

Cool 1989; Wernerfelt 1984), knowledge-based (Grant 1996; they are often seen primarily as conduits of other, knowledge-

Liebeskind 1996; Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995; Spender 1989, based, resources, such as when a microprocessor is viewed as

1996), and service-dominant logic (Lusch and Vargo 2014; having embedded within it knowledge of various rules of

Vargo and Lusch 2004, 2008a, 2008b, 2011, 2016) views of logic and, partly by virtue of this, the ability to apply

organizing. They are relevant to our purposes for three rea- sequences of instructions to binary data. While consistent

sons. First, in placing resources at the center of organiza- with the emphasis on competences, the devices themselves

tional performance, they have all had to pay attention to tend to be treated in an ontologically naïve and undifferen-

distinguishing different kinds of resource, and then especially tiated way. Despite dealing with a vast range of digital

with regard to the nonmaterial and fluid nature of certain technologies, and while recognizing important differences

types of resource. Second, they are all well developed and between technologies along various operational dimensions

influential in IS research. The manner in which they render such as function, scale, technical platform, and so on,

digital technology is, therefore, highly relevant to the disci- individual accounts typically fail to differentiate meaningfully

pline.2 Third, and finally, the problems we identify with the between things in terms of their mode of being and other basic

three views are representative of weaknesses in the concep- properties. Instead, digital devices, whether smart objects, IT

tualization of digital technology in IS research more widely. infrastructures, software applications, or media files, tend to

be grouped into a single, ontologically homogenous category

Let us begin by observing that, in characterizing digital of IT resource, and where such resources are often portrayed

technologies as resources, all three views devote considerably as straightforwardly physical things.

more attention to IT-related competences in the form of

managerial and technical knowledge, skills, and processes, There is no shortage of examples. From the resource-based

than they do to the devices involved. This is especially true perspective, categories such as IT assets (Nevo and Wade

of work drawing on the resource- and knowledge-based 2010), information technology (Barney and Clark 2007),

views. Wade and Hulland’s (2004) typology of “key IS technological IT resources (Melville et al. 2004), IS infra-

resources,” in which seven of the eight main categories of structure (Wade and Hulland 2004), and tangible IT resources

resource identified are different types of competences, is a (Bharadwaj 2000) all share this quality of ontological homo-

striking example. But more typical, perhaps, is the bipartite geneity. In some cases, the supposed material nature of the

classification employed by Melville et al. (2004), who distin- category’s constituents is made explicit, as with Melville et al.

guish between human and technological IT resources and (2004) ) who describe technological IT resources as a subset

associate competences with the former and devices with the of physical capital resources and Bharadwaj (2000), who

latter. The subsequent emphasis is then overwhelmingly on describes tangible IT resources as “physical IT infrastructure

competences, this because most digital devices are seen as components” (pp. 171-172). In other cases, the mode of being

lacking the characteristics—being difficult to imitate, transfer, of the constituents is left implicit, although the usual impres-

or substitute another resource for—associated with sustained sion is that such things can be readily understood as material,

competitive advantage (Melville et al. 2004; Nevo and Wade physical, things.

2010; Ravichandran et al. 2005; Santhanam and Hartono

2003; Stoel and Muhanna 2009). However, and while there While the service-dominant logic view exhibits a similar lack

is no doubt about the importance of competences as a source of ontological differentiation, it does provide a concep-

tualization of the dual role of digital technologies as both

operand resources, capable only of enabling action, and

2

The resource-based (Bharadwaj 2000; Chuang and Lin 2017; Drnevich and operant resources, capable of initiating action (Akaka and

Croson 2013; Mata et al. 1995; Melville et al. 2004; Mithas et al 2012; Nevo Vargo 2014; Lusch and Nambisan 2015; Nambisan 2013).

and Wade 2010; Ray et al. 2005; Santhanam and Hartono 2003; Wade and

This distinction might be thought to invite ontological reflec-

Hulland 2004) and knowledge-based (Alavi and Leidner 2001; Choi 2018;

Choi and Ryu 2015; Mao et al. 2015; Pavlou et al. 2005; Reychav and tion, since within the service-dominant logic view operand

Weisberg 2009; Setia et al. 2013; Tanriverdi 2005) views have been widely resources are widely seen as material things (e.g., machinery)

used in IS studies of IT-based resources as sources of competitive advantage and operant resources as nonmaterial (e.g., competences).

and the mechanisms through which this may occur. The service-dominant Yet despite provocative examples of the operant ability of

logic view is particularly prominent in recent IS research on digital service

innovation (Eaton et al. 2015; Lusch and Nambisan 2015; Scherer et al. 2015;

digital technologies to trigger exchange and even innovation,

Sriviastava and Shainesh 2015). there is little on the ontological status of the relevant devices,

4 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

whether nonmaterial as well as material entities are being In contrast, the service-dominant logic view has recently seen

considered, and the link between this and the twin roles theoretical developments that address some of the social

ascribed to digital technology. aspects of digital technology. These developments are in

relation to the notion of service ecosystems, understood as

The consequences of ignoring ontological considerations of systems of “resource-integrating actors connected by shared

this kind are significant, since it limits scope to account for institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through

properties things possess by virtue of their mode of being and service exchange” (Vargo and Lusch 2016, pp. 10-11; see

for theorizing the relationship between ontologically distinct also Akaka et al. 2013; Vargo and Lusch 2011; Vargo and

kinds of entity. This problem is likely to be especially severe Akaka 2012). Institutional arrangements here refer to the

in the digital context given that digital devices are typically kind of social structures mentioned above, and where these

complex combinations of the material and the nonmaterial. are seen as both an important type of resource and a key part

of the context within which other resources exist and value

One area in which such issues come to the fore is with respect creation takes place (Akaka et al. 2013). But these develop-

to the informational aspects of digital technologies and the ments have yet to take hold in IS research and so there has

unique ways certain kinds of entities are able to facilitate the been little progress so far in theorizing the social aspects of

storage and transmission of information. It is significant here digital technology from this perspective (although Akaka and

that all three views embrace some notion of resource lique- Vargo (2014) discuss some of the social aspects of technology

faction—“decoupling of information from its related physical generally). Further, there remains considerable scope for the

form or device” (Lusch and Nambisan 2015, p. 160)—seen as development of the service-dominant logic view in this

central to the way digitization and digital communications respect, particularly in regard to the identity of digital objects

have affected knowledge management, collaboration, organi- and how this is related to social positions and their social

zational agility, innovation, and so on (Bharadwaj 2000; Choi positioning.

2018; Lusch et al. 2010; Lusch and Nambisan 2015; Lusch

and Vargo 2014; Mao et al. 2015). As things stand, however,

all three views require a more thorough theorization of this

idea to be able to fully explore its implications. While

A Theory of Digital Objects

relevant concepts are hinted at, for example Lusch and Vargo

Objects

(2014, p. 141) referring to “information resources” and

Barrett et al. (2015, p. 142) to resources “in which the primary

We now present our theory of digital objects, beginning with

component is information,” these notions are usually left

a consideration of objects themselves. We start from a

unexplored. Claims to the effect that liquefaction enables

general, high-level, conception of objecthood and then work

“intertwining the virtual and material layers of work in dif-

down to the main kinds of object germane to the digital world.

ferent ways to enhance organizational performance” (Lusch

and Nambisan 2015, p. 160), suggestive as they may be, are

thus left essentially metaphorical. A Conception of Objects

Our remaining comments concern the social aspects of digital Following Faulkner and Runde (2013), we take objects at

technology, particularly the identity of digital objects, their their most abstract to be entities that possess two charac-

use, and “fit” generally within the social world. The resource- teristics: first, that they endure, and second, save for those so

and knowledge-based views have done little to theorize these basic as not to be composed of constituent parts, that they are

aspects, save for what they say about social complexity: the structured. By an object enduring we mean that it is a type of

idea that certain kinds of resources are enmeshed in webs of continuant, namely something that exists through time and is

social relationships and so intrinsically dynamic, evolving fully present at each and every point in time over the period

over time, and difficult for an organization to control or other of its existence. In this respect, objects may be contrasted

organizations to imitate (Barney and Clark 2007, Chen et al. with things such as events, processes, and other kinds of

2014; Mata et al. 1995). This property is only rarely asso- occurrent that take place and whose different parts occur at

ciated with devices, however, digital or otherwise. Further, different points in time.3 By structured, we mean that an

and this is symptomatic of resource- and knowledge-based

views generally, there is minimal reflection on matters of

3

social ontology—the stuff of the social world, social rules, The terms continuant and occurrent, as well as some of the later distinctions

relations, and the like—that would provide a conceptual and categories we employ (e.g., the distinction between material and non-

material objects, the notion of syntactic objects), are closely related to a

foundation for, and enable more detailed elaboration of, the variety of similar terms found in work in computer and information science

idea of social complexity. aimed at constructing formal and comprehensive taxonomies of the entities

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 5

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

object is composed of a number of distinct parts, objects in objects are commonplace, not least in the digital realm, and

their own right, that are organized in some way. Thus a typi- we will have more to say about them when we discuss digital

cal flatbed scanner, for example, comprises a light source, objects and the idea of bearers of nonmaterial objects. For the

image sensor, glass panel, control circuitry, and various other moment, the pertinent point about hybrid objects is that they

components, arranged in a way that renders the object as a are necessarily material objects, with the physical mode of

whole capable of converting an analog image into digital being of their material components sustaining the materiality

form. of the hybrid object as a whole.

The category of objects is a broad one on this conception,

extending beyond the kind of physical objects just described Syntactic Objects

to things such as individual human beings and enduring

assemblages of humans and nonhumans. From this point on, While there exist many different kinds of nonmaterial object,

however, we restrict the term object to those that are the most important for our purposes are syntactic objects.

inanimate, in the sense of having exclusively inanimate com- These are objects that consist of symbols arranged into well-

ponents and being, as a whole, inanimate things themselves. formed expressions, where well-formed means that these

This is a departure from Faulkner and Runde (2013) and one expressions adhere to the syntactical and semantic rules of the

we take for two reasons. The first is that it brings us closer to language in which they are couched. Take for example a

ordinary language, where many are uncomfortable describing news article such as that published in The Economist (January

humans and, sometimes, animals as objects. The second rea- 13, 2018) entitled “Beyond Bitcoin: Bitcoin Is No Longer the

son is that it makes for a clear and more natural way of Only Game in Crypto-Currency Town.” Here the symbols

maintaining the distinction between inanimate things and the consist of letters and punctuation marks, the expressions are

larger systems involving humans that feature in the discussion words and sentences, and well-formed means that these words

of social positioning below. and sentences conform to the rules of the English language

and convey the intended meaning of the author. Other

examples of syntactic objects include natural language texts

Material and Nonmaterial Objects such as novels, manuals, and contracts, and textual entities in

artificial languages such as musical notation, Morse code, or

The category of objects can be divided into material and

mathematics.

nonmaterial variants. While the term material has many

meanings (Leonardi 2010), we use it to refer specifically to

It is easy to see that the news article, and by extension any

the physical mode of being of an object, a property we see as

syntactic entity, satisfies the two criteria for nonmaterial

necessarily involving the object concerned having spatial

objecthood set out above: that it is an object and that it has a

attributes such as shape, volume, mass, and location, and

nonphysical mode of being. On the first criterion, the article

where this physicality is manifested in the structure of that

is an object by virtue of being both a continuant and struc-

object, namely its component parts and how these are com-

tured. With respect to the former property, the article is a

bined or arranged. Examples of material objects include

continuant because, once created, it endures over time rather

scanners, smartphones, and servers. Nonmaterial objects have

than being something that takes place in time. With respect

a nonphysical mode of being and so lack spatial attributes of

to the second property, recall that an entity is structured if

the sort just mentioned. Examples here include syntactic

composed of distinct parts organized in some way. In the

objects such as the news articles, operating systems and

case of material objects, structure refers to their physical com-

application software examined below, as well as other kinds

ponents, spatial arrangement, interactions, and so forth. In the

of nonmaterial objects such as protocols, procedures and

case of nonmaterial objects structure again refers to their con-

conceptual schemes.

stituent parts, arrangement, and interactions, but where these

are no longer physical attributes of the object. Returning to

We use the term hybrid to refer to objects that comprise both

our news article, the component parts are letters and punctua-

material and nonmaterial objects as component parts. Such

tion marks arranged to form words and sentences, and this

arrangement is a logical property insofar as the words and

sentences conform to the rules of the language in which it is

and relations found in a given domain. This work is also referred to as written and capture what the author intended to convey.

ontology (see for example Lando et al. (2008) and Poole and Mackworth

(2010, Chapter 13)), although in this case primarily concerned with estab- On our second criterion, the news article is a nonmaterial

lishing vocabularies that can be shared across a range of different applica-

tions rather than the project of understanding and articulating constituents of

object by virtue of its nonphysical mode of being. That is, as

reality that we are concerned with in the present paper. an entity consisting solely of symbols it has none of the

6 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

intrinsic spatial qualities associated with the material entities contains four smaller circles, with the largest of these

described above. While it may be printed or otherwise depicting syntactic objects as a proper subset of nonmaterial

inscribed on various material objects such as magazine pages objects and the next largest depicting bitstrings as a proper

and computer screens, the article itself is at bottom nothing subset of syntactic objects. The two smallest circles then

more than an aspatial series of letters and punctuation marks. depict the set of bitstrings as comprising two proper subsets:

program files (PF) and data files (DF).

Bitstrings

Digital Objects

As the examples already mentioned illustrate, syntactic

objects are ubiquitous in the digital world. However, one type The final category of object we single out is digital objects,

of syntactic object stands out as fundamental. This is the which we define as objects whose component parts include

bitstring, a type of syntactic object made up of bits, the 0s and one or more bitstrings. The set of digital objects, therefore,

1s employed in a binary numbering system, where these bits includes individual bitstrings as a limit case, but generally

are structured according to an appropriate file format so as to refers to a far broader category of objects, usually hybrids, in

be readable by the kind of computer hardware for which they which bitstrings are combined with various types of material

are intended. and nonmaterial components. Thus, in addition to individual

programs and data files, the set of digital objects includes

Bitstrings, often called computer files, are one of the corner- relatively small-scale physical devices, ranging from com-

stones of the digital revolution, since the information stored puter systems, components, and peripherals, including the

and manipulated on almost all silicon-based von Neumann kinds of material and nonmaterial bearers of bitstrings dis-

computers, including traditional transistor-based digital PCs, cussed below, to everyday artifacts with embedded computing

is encoded in bitstrings. Bitstrings divide into two categories: capabilities, as well as larger assemblages such as information

program files and data files. Program files encode sequences systems, computer networks, and digital ecosystems in which

of logical operations, with iterations and conditions, that con- the component parts may be widely spatially distributed, and

stitute the instructions for carrying out particular kinds of complexes of predominantly nonmaterial objects, such as

computation on a given class of hardware. Examples include software suites, web sites, and digital archives. As these

operating systems, applications such as spreadsheet and word examples illustrate, digital objects may be either material or

processing software, browsers, smart phone apps, and games. nonmaterial objects, with hybrids acquiring the physical mode

Data files encode the data used by a computer program or of being of their material components.

system, including documents, datasets, images, videos, and

audio recordings.

Bearers of Nonmaterial Objects

The Picture So Far Our description of the basic constitution of digital objects in

place, we now turn to a topic we regard as fundamental to the

The categories of object introduced so far are summarized in place of digital, and other kinds of, objects in the digital

Figure 1, a Venn diagram in which the rectangular boundary domain. This is the idea that nonmaterial objects may be

denotes the universe of objects and where the two largest inscribed onto, contained within. or borne by other objects,

circles represent the set of material and nonmaterial objects. something we capture with the general notion of bearers of

Since any object must either be material or nonmaterial, there nonmaterial objects.

are no elements lying outside of these two circles. Further-

more, since an object cannot be both material and non-

material, these sets are disjoint and the two circles therefore Material Bearers

nonintersecting. The circle denoting material objects contains

a smaller circle that depicts hybrid objects as a proper subset A basic feature of nonmaterial objects is that in order to be

of material objects.4 The circle denoting nonmaterial objects accessed—to be used, stored, passed to others, etc.—they

must in some way be inscribed onto, contained within, or

borne by a material object of some kind. Thus, for a news

4

While it is tempting to think that hybrid objects should be represented as an article to be read by a human being, for example, it must be

intersection of the set of material objects and the set of nonmaterial objects, displayed on a suitable material object, whether this be the

this would make them at once material and nonmaterial objects, which is not

screen of a computer monitor, tablet, or smartphone, or the

possible. Instead, and notwithstanding their also having nonmaterial compo-

nents, hybrid objects necessarily have a physical mode of being by virtue of page of a newspaper, magazine, or book. Similarly, if that

their material components. article is to be archived, lent to another person, edited, and so

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 7

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Universe of Objects

Material Nonmaterial

Hybrid Syntactic

Bitstrings

PF

DF

Figure 1. Types of Objects

on, it must be held or maintained on an appropriate material (kinds of) material bearers, whose location is largely con-

object. Generalizing, we call any material object on which a strained only by the limits of international travel and

nonmaterial object is so inscribed a material bearer of that communications technology.5

nonmaterial object. Notice that a material bearer is neces-

sarily a hybrid object according to our earlier characterization Material bearers are, of course, ubiquitous in the digital realm

of objects. and represent an important type of digital object. We have

already mentioned one example, namely the various kinds of

Two features of the object–bearer relation warrant emphasis screens found not only in laptops, tablets, and smartphones,

here. The first is the ontological distinction it implies be- but also in many industrial and household devices, vehicles,

tween a nonmaterial object and the material objects on which and so on. Another is the numerous different kinds of media

it is inscribed. That is to say, however much access to a device used to store bitstrings in machine-readable form,

nonmaterial object may depend on its material bearers, that including CD- and DVD-ROMs, hard disk and solid-state

nonmaterial object is distinct from any and all of these drives, and memory cards.

material things by virtue of possessing its own particular and

separate attributes. One such property is its nonmaterial mode The main ideas involved here are illustrated in Figure 2, in

of being, from which flow others such as its not degrading which three different material objects (each denoted by a grey

with repeated use and what economists call the property of rectangle)—a hard disk drive, microSD card and DVD-

non-rivalry that its use by one person in no way impinges on ROM—serve as the material bearer of the same nonmaterial

its simultaneous use by any number of others. The distinction object (denoted by a white rectangle), a particular bitstring.

is also essential if we are to recognize the separate properties In each case the object–bearer relation is illustrated by

of material bearers, something of considerable import not showing the nonmaterial object located on top of the relevant

least because an object’s suitability as a material bearer material object, with the bearer in each example being the

depends in part on the properties of that thing. Thus where an digital (and hybrid) object comprising the bitstring and the

object is intended to serve as a material bearer for the relevant material object (i.e. the combination of white and

purposes of archiving a nonmaterial object, properties such as grey rectangle in each case).

durability and portability are likely to be important attributes

of the material object concerned. If instead the primary role

of the bearer is to enable a nonmaterial object to be read,

visual clarity is likely to be a more important property.

The second feature is that, barring physical, legal, or other 5

The term copies is often used in relation to the instances of what we are

constraints, there is no limit to the number of different (kinds calling material bearers of a nonmaterial object, for example, when a maga-

of) material objects on which a given nonmaterial object may zine page on which a news article is inscribed is described as being a copy of

be borne at any point in time or to the range of locations these that article. We avoid the term copy, however, because it risks collapsing, or

various bearers may occupy. Thus many nonmaterial objects, at least obscuring, the distinction between a nonmaterial object and its

material bearers. For example, the page of the magazine (a material object)

the aforementioned news article being a prime example, are on which an article (a nonmaterial object) is inscribed is not literally a copy

nowadays borne concurrently on a vast range of different of that article.

8 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Bitstring

Hard disk drive

Bitstring

microSD card

Bitstring

DVD-ROM

Figure 2. Three Material Bearers of the Same Bitstring

Our earlier emphasis on the ontological separation between a The idea of nonmaterial bearers is fundamental to the digital

nonmaterial object and its material bearers—in essence, that world, particularly with respect to the role played by bitstrings

they are separate entities with their own distinct properties— and thus digital objects. We have already noted that modern

should in no way be taken to imply a more general separation computing is founded on the manipulation of information

that prohibits causal interactions between the two kinds of encoded in binary form. The significance of bitstrings can

entity. To the contrary, such interactions lie at the heart of then be understood in terms of their role as nonmaterial

our account. Thus, and as we have already made clear, bearers of the various kinds of nonmaterial object corre-

material bearers are vital to practical engagement with non- sponding to the different types of information employed in

material objects: to be accessed, a nonmaterial object must be computing. Thus a program file is the bearer of a set of

borne on a material object. Another example arises in relation instructions associated with a particular series of computa-

to the creation of new nonmaterial objects, a process that may tions, while a data file is the bearer of an image, document,

involve its author reflecting on the nature of the material on dataset, or some other kind of data.

which an object will subsequently be borne. Thus whether an

author opts to include charts, tables, or other figures within a Many of the points made earlier in relation to material bearers

news article may well be influenced by their expectations apply to nonmaterial bearers as well. Again, it is necessary to

regarding the kinds of material bearer(s) on which that article be clear about the ontological distinctions involved: just as it

is likely to be displayed—for example, whether it will be pub- is important to avoid conflating a nonmaterial object with its

lished online as well as in hard copy and, if so, whether most material bearers, it is important to avoid conflating a non-

online readers will read it via a smartphone or via a larger, material object with its nonmaterial bearers. Thus a news

static, computer monitor. article may be borne by a variety of different bitstrings

corresponding to different file formats such as DOCX, TXT,

and XML. Yet the article is distinct from any and all of these

Nonmaterial Bearers bearers since, while the sequence of words that comprise it

will be the same in each case, the bitstring bearers differ, each

In addition to material bearers there are also nonmaterial with their own distinct structures and properties. As before,

bearers of nonmaterial objects. These are cases in which a the properties of these different bearers matter, one illustration

nonmaterial object is borne by or contained within a syntactic of which is the way creation of a nonmaterial object may be

object of some kind. Consider a software testing protocol, a influenced by the attributes of its intended bitstring bearer.

nonmaterial object consisting of a series of procedures aimed Thus the producer of an audiovisual recording is likely to be

at verifying the functionality of some piece of software. The influenced by the properties of the particular multimedia

protocol is not itself a syntactic object as it is not composed format to be used, for example what kinds of information can

of symbols. However, the protocol may be given linguistic be included (e.g., single or multiple audio streams, subtitles,

expression in a variety of ways, such as when it is docu- metadata, etc.), whether the encoding involves lossless or

mented as text for the pages of a training manual. The latter lossy data compression, and so on.

text, a syntactic object in its own right, is also a nonmaterial

bearer of the protocol. Generalizing, we call any syntactic The introduction of nonmaterial bearers also brings additional

object in which a nonmaterial object is so borne or contained features of the object–bearer relation into focus, the most

a nonmaterial bearer of that nonmaterial object. significant of which is that there may be many layers of

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 9

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

nonmaterial bearers involved, such that a nonmaterial object textual expression of the protocol) involves displaying, and

may be borne by a nonmaterial object, which is itself borne by perhaps subsequently printing, the relevant text.

a nonmaterial object (and so on). This idea holds particular

significance in relation to the information stored in bitstrings.

Continuing our earlier example of the software testing proto- Computation

col, consider what happens when a bitstring bearer of the text

to be used in the training manual is created in MS Word. The We now offer some brief observations on computation, the

resulting DOCX file is itself a nonmaterial object, but at the real-time processes performed by digital computers that

same time also a nonmaterial bearer of the syntactic object involve the algorithmic manipulation of information borne by

that is the linguistic expression of the protocol, which is itself bitstrings. These processes, largely implicit in our account so

a nonmaterial bearer of the original nonmaterial object, the far, are relevant here for their existential relationship with

protocol. If that DOCX file is compressed as a ZIP file, that digital objects. This relationship is two-way, the existence of

ZIP file is then the bearer of a bearer of a bearer of the computation at once depending on and contributing to the

protocol.6 In principle, such layering may be repeated existence of digital objects.

indefinitely. However, all such layers must ultimately bottom

out on a material bearer of some kind, since, as we noted Consider first how the existence of computation depends on

earlier, to be used, stored, or communicated, a nonmaterial certain kinds of digital object. Recall that we described pro-

object must ultimately be borne on a material object. Figure gram files as the bitstring bearers of sets of logical operations

3 summarizes our conception with (layers of) nonmaterial corresponding to the instructions for carrying out particular

bearers now included. types of computation. Whenever a program file is executed

on appropriate hardware this results in a real-time (series of)

This idea of the repeated layering of nonmaterial objects, process(es) of computation, with sequences of events trig-

facilitated by the capacity of bitstrings to act as bearers, seems gered according to the semantics of the instructions encoded

to us one of the defining features of digital technology and a in that program file.7 There are then two ways that the exis-

major factor in what makes contemporary digital objects tence of computation depends on digital objects, including

unique. Notice that the layering involved here is quite dif- program files and computer systems. The first concerns the

ferent from the more familiar notion usually referred to as the initial coming into existence of a computational process, the

layered architecture of digital technologies. This latter idea second with its ongoing existence over the period it runs.

refers to the hierarchical structuring, within devices, of layers

of heterogeneous kinds (such as contents, services, network, Recognition of this connection brings many issues into focus,

device), and where each layer constitutes a distinct, and and the shift to distributed computing provides a particularly

largely separable, design hierarchy (Yoo et al. 2010). salient example here. Consider something as seemingly

simple as visiting a website. The website, a digital object in

We use the term translational actions to refer to practices its own right, comprises bitstring encodings of content such

associated with movement from one layer of bearer to as text, images, and audio, as well as scripts governing its

another. Thus, in the preceding example, moving downward appearance and user experience. Actually accessing the web-

from the top of Figure 3, the original protocol is first captured site, however, requires a much larger assembly of other,

in text (e.g., is written up), this text then encoded in a DOCX mostly digital, objects, including desktop and handheld

file (e.g., is input via keyboard or speech-recognition), this devices on the user side, servers, routers, switches, and the

file then converted to ZIP format (e.g., using compression like on the server side, and the networking equipment linking

software), before finally being stored on a material bearer the two. Many of these objects are themselves capable of

(e.g., saved on a hard disk drive). Moving in the opposite computation, and visiting a website accordingly involves a

direction, accessing the ZIP file from its material bearer, and host of separate but interconnected processes of computation,

subsequently the DOCX file from the ZIP file, involves both concurrent and sequential, of variable length and

retrieval using relevant software, while converting the non- complexity, running on a range of distinct platforms across

human-readable DOCX file to a human-readable bearer (the different locations. The distributed nature of the computation

here, increasingly reflected in devices designed for an Internet

of Things, flows from continued growth in internet access,

6

Another example of this kind of layering occurs in relation to computer

programming, where a given set of logical operations may be encoded in a

variety of different higher-order programming languages, each giving rise to

7

a syntactic object, the source code, that is a nonmaterial bearer of that instruc- In ordinary language, the term computer program often refers to both the bit-

tion set. Each of these syntactic objects could then be encoded in binary as string object and the processes of computation involved in its execution,

machine code for a variety of different processors, giving rise to multiple conflating the two kinds of entity and thereby obscuring the relationship

bitstring encodings of the same source code. between them.

10 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Nonmaterial object (e.g., software testing protocol)

Nonmaterial bearer (e.g., textual expression of the protocol)

Nonmaterial bearer (e.g., DOCX encoding of the textual expression)

Nonmaterial bearer (e.g., ZIP encoding of the DOCX file)

Material bearer (e.g., hard disk drive)

Figure 3. Layers of Nonmaterial and Material Bearers

coupled with technical developments, particularly in relation The second issue concerns bearers, building on the fact that

to mobile and smart devices, in terms of miniaturization, the creation of new bitstrings usually also entails the creation

performance, and cost. of new material and nonmaterial bearers. This might be

because the new bitstring is itself a bearer of a nonmaterial

Now consider how the existence of digital objects might object (of text, audio, etc.) and/or because the new bitstring

depend on computation rather than the other way around. The must itself be borne in some form (e.g., stored on a local

basic point here is the simple one that processes of com- drive, transferred to the cloud and so on). What this points to

putation are to varying degrees involved in the creation of is that computation typically involves the creation not simply

many types of digital object. Bitstrings are an obvious of new bitstrings—perhaps short-lived, perhaps not; perhaps

example, not least the bearers of the ceaseless flow of emails, located in various places reflecting the distributed nature of

texts, and tweets, news articles and blogs, audio, still images, computing—but also a variety of additional digital objects in

and video on the Internet. But the point applies much more the form of new material and nonmaterial bearers. Transla-

widely once we recognize the role of computation in the tional actions feature heavily here, all to do with the computa-

conception, design, and production of many manufactured tion involved in moving between layers of bearers, as when

digital objects, including computers themselves and the the HTML code sent by a website’s server is converted to

various ancillary devices and equipment involved with their text, images, and so on by the web browsing client, or when

use. However, in contrast to how computation depends on data input by a user is transmitted back to the server and

existing digital objects, the ongoing existence of new digital stored.

objects in most cases, once they have been created, no longer

depends on computation.

The Social Positioning of Digital Objects

Again, recognition of the existential dependence of digital

objects on computation brings a variety of issues into focus, Thus far we have concentrated on the intrinsic features of

and we will mention two that arise in relation to the creation digital objects, portraying them as discrete entities with innate

of new bitstrings. The first concerns the difference between properties that exist and endure independently of their setting.

bitstrings that are the intended outcome of a task and those In this last part of our theory, we turn to their context-

that are not. Examples of the former include the cases in dependent aspects, in particular the way in which the kind of

which a set of media files is compressed to create a single thing they are—smart phone, search engine, banking app, or

archive file, or an audio track ripped from a CD to create an whatever else they may be—depends on their social

MP3 encoding. Here computation is about the use of existing positioning.

digital objects to combine and recombine existing nonmaterial

objects to achieve the desired outcome. Yet in other cases,

and perhaps more typically, new bitstrings arise during com- Social Positioning: Overview

putation as a by-product of the use of digital objects. Cookies

generated while visiting a website are a familiar example, or The perspective on social positioning we draw on is part of a

when an activity tracker generates bitstring encodings of broader social theory developed by Tony Lawson (1997,

metrics such as steps taken, calories burnt, and heart rate. 2003, 2012, 2015, 2016; also see Faulkner et al. 2017). The

New bitstrings of this kind often have a short life span, guiding idea is that, in being assigned a position within some

intended only as temporary files, and may be subject to system by some community, an entity acquires the social

continued modification as computation and use of the relevant identity associated with that position. A social position is a

digital object proceeds. specific status within a system that locates its occupant as a

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 11

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

component of that system. The social identity of any entity is In assigning an entity to a particular position within a system

then the kind of thing that entity is by virtue of the social the goal is, in general, to achieve a close fit between the

position it occupies. Social positions typically exist indepen- intrinsic capacities of that entity and the requirements of the

dently of, and usually prior to, any individual occupant, system function associated with that position. Where an

something which therefore applies also to the identities they entity’s capacities are well suited to fulfilling its system func-

inform. tion, the positioning is likely to endure. Where the match is

a poor one, however, the positioning is unlikely to be sus-

Perhaps the most familiar examples of social positioning are tained. Most human artifacts, digital or otherwise, are of

those that involve the employment of human beings within the course designed and manufactured with the position they are

systems we commonly refer to as organizations, such as the to occupy in mind, so that they possess capacities tailored to

position of thoracic surgeon within a hospital. This position the specific system functions they are intended to serve. But

denotes a particular status within the hospital and where it is it may happen that an object designed with one system

by virtue of being assigned that status, and so occupying the function in mind may nevertheless be repositioned and

relevant position, that its occupant acquires the associated acquire a different identity and system function as a result

social identity and so is a thoracic surgeon both within the (Cardinale and Runde 2019; Faulkner and Runde 2009).

hospital and the wider community.

Rights and Responsibilities: Social positions are also the

locus of numerous rights and responsibilities, which position-

The Case of Digital Objects occupants become subject to on entering a position. Again,

the point is familiar in the context of employment-related

One of the features of Lawson’s view is that it applies also to positions, with the occupant of the position of thoracic sur-

the organization of systems that include, or are composed geon having the right to decide clinical priorities within their

entirely of, inanimate entities (Faulkner and Runde 2013; department, as well as the responsibility to keep patients

Lawson 2012, 2015, 2016). Of particular relevance here is informed of treatment options, associated risks, and so forth.

the case of positioned objects, where the positions concerned While objects do not themselves enjoy rights or bear respon-

have to do with the practical use to which objects are put. sibilities in the way humans do, the positions they occupy are

Take the class of devices we know as MRI scanners. In the also the subject of rights and responsibilities pertaining to

same way that the social position of thoracic surgeon locates their use, maintenance, and so on. Thus, the right to order

its human occupant as a component of the larger system of a MRI scans may be restricted to particular physicians and

hospital and confers on them the social identity of thoracic

imaging conducted only by suitably qualified radiographers

surgeon, the social position of MRI scanner likewise locates

within a hospital, while the scanner’s warranty imposes

its object occupant as a component of the larger system of a

obligations on its manufacturer and might restrict aspects of

hospital and confers on it the social identity of MRI scanner.

its installation, modification, and so on.

Similarly, the position of electronic medical records (EMR)

software locates its bitstring occupant as a component of a

As these examples show, the rights and responsibilities asso-

larger health care system and confers on that bitstring the

ciated with social positions are typically two-sided, with the

social identity of EMR software.

rights (responsibilities) of one position matched by corre-

sponding responsibilities (rights) associated with other

Aspects of the Social Positioning of Digital Objects positions. This feature reflects the internal-relatedness of

social positions, where the existence of any one social

We will briefly note these three key aspects of the social position presupposes the existence of others (and vice versa).

positioning of digital objects: system functions, rights and Relationality of this sort is common in the digital realm,

responsibilities, and the reproduction and transformation of whether between social positions occupied by digital objects

social positions. alone (e.g., MRI scanner and digital MRI image), between

social positions occupied by digital objects on the one hand

System Functions: Every social position carries with it an and humans on the other (MRI scanner and MRI technician),

expectation that its occupant will contribute to the perfor- or between social positions occupied by humans alone (e.g.,

mance of the relevant system in certain ways, something we surgeon and surgery patient). All of these cases exhibit a

call a system function. This observation applies equally to form of mutual, or co-, constitution between the entities

positioned humans and positioned objects: just as whoever concerned, arising at the level of the social positions they

occupies the position of thoracic surgeon within a hospital is occupy and the social identities they acquire.

expected to treat patients suffering from thoracic disorders, so

the digital object that occupies the position of MRI scanner is The Reproduction and Transformation of Social Posi-

expected to produce detailed images of the inside of the body. tions: Social positions, as well as the relations in which they

12 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

stand and the social identities they inform, exist through being keenly contested—continued growth in both the number and

continuously enacted or performed, and thereby reproduced, variety of bitstrings available to download suggests such

in the practices associated with them. Thus, the social posi- markets are likely to become an increasingly important feature

tion of MRI scanner, as well as its relations to other social of digital commerce. Indeed, companies such as Amazon,

positions and its associated social identity, exists and endures Apple, and Microsoft already hold patents on technologies

through practices such as physicians ordering, radiographers aimed at enabling secondary trade of this sort (Streitfeld

carrying out, and radiologists reporting on the images pro- 2013).

duced by MRI scans of patients. Computation is involved in

many of these practices, and the social positions associated The advent of these markets raises a host of theoretical and

with digital objects, together with their associated relations practical issues, ranging from technological challenges

and identities, would not, therefore, generally exist but for associated with designing suitable online platforms to eco-

processes of computation. nomic consequences that might flow from the monetization of

end-users’ intangible digital “assets.” Our present interest,

Social positions may, of course, also be transformed through however, lies in how our theory may facilitate study of this

human practices, driven by any manner of things including phenomenon and to this end we will concentrate on two

technological developments, accidents, and novel practices particular aspects. The first is ways in which the intrinsic

elsewhere. They may atrophy over time (e.g., the position of properties of bitstrings render their secondary markets dif-

floppy disks associated with legacy IT systems), mutate (e.g., ferent from those for pre-owned material objects. The second

the position of camera as digital photography became wide- is the role of material bearers, particularly with respect to

spread), and new ones emerge (e.g., the position of activity some of the main legal issues associated with the resale of

tracker). The view on social positioning we are advocating downloaded bitstrings. Both aspects highlight the importance

can, therefore, accommodate both continuity and change in of ideas contained in our theory, first, in being able to account

the digital realm, always mindful of the relational and for the characteristics of nonmaterial objects such as bit-

performative aspects of the positioning, identity, and use of strings, and second, in providing the ontological basis for

digital objects, but never so as to lose sight of their intrinsic distinguishing nonmaterial objects from their material and

properties. nonmaterial bearers, and for capturing the relationship

between the two.

The exposition of our theory now complete, we move on to its

potential value to IS research. There are various ways that the intrinsic properties of bit-

strings render markets for pre-owned, downloaded, applica-

tion software and media files different from those for second-

hand material items such as motor vehicles, furniture, or

Implications clothes. We highlight two here. The first is that, by virtue of

their nonmaterial mode of being and combined with the

Given the abstract level at which it is pitched, we believe that availability of low-cost bearer technologies and the reach and

our theory could be fruitfully applied in many areas of IS speed of the Internet, the storage and distribution costs asso-

research. In what follows, we focus on demonstrating its ciated with their online exchange are negligible. It follows

utility as a conceptual framework for investigating phenom- that secondary markets for downloaded bitstrings have the

ena in which digital objects predominate and its potential to potential to be highly efficient, with low transaction costs

inform existing theoretical perspectives in IS. ensuring that most opportunities for trade between potential

buyers and sellers can be achieved. By comparison, the phy-

sicality of material objects can imply larger transactions costs

Bitstrings, Bearers and Markets for and thus less efficient secondary markets. Thus while the

Secondhand Software potential buyer of a secondhand piano may value it more

highly than its current owner, if the cost of transferring that

We begin with an empirical example: the recent emergence object from seller to buyer is too great the exchange will not

of secondary markets for pre-owned downloaded bitstrings occur.

such as application software and media files. Currently

organized around a small number of web-based firms oper- The second way in which the intrinsic features of bitstrings

ating as online intermediaries, these markets make it possible make a difference is that, unlike most material objects, they

for owners of legally downloaded bitstrings to resell them do not degrade with use or age. Pre-owned bitstrings can,

over the Internet. While such markets are in their infancy— therefore, genuinely be sold as being in like-new condition,

with intermediaries only willing to deal in certain kinds of with there being no difference in quality between a file

bitstrings and where the legal status of even this trade is purchased direct from a retailer such as the iTunes Store or

MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019 13

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

one bought from an existing end-user. This has at least two copies, or what we call material bearers, of a copyrighted

important implications. The first is that these markets avoid work. As usually understood, the FSD creates an exception

the classic lemons problem often associated with markets for to this right such that ownership of a lawfully acquired

used material goods (Akerlof 1970), where trade may be material bearer of a copyright-protected work permits distri-

reduced or fail to take place entirely simply because buyers bution of that particular material bearer. Thus the owner of a

are unable to distinguish high from low quality items, and legally purchased paperback copy of a novel is permitted to

where sellers and buyers may have to invest in costly dispose of, for example resell, that item as they wish.

signaling and screening activities to overcome these

informational asymmetries. The second is that the non- The key issue in relation to the legality of secondary markets

degradability of bitstrings is a key factor in media and for downloaded bitstrings is whether or not the FSD applies

application software companies’ concerns about secondary in this setting. To the extent that bitstrings mirror the paper-

markets and their motivation for challenging the legality of back example just described, the FSD has transferred to the

such trade. For if pre-owned bitstrings are like-new, their digital realm with little difficulty. Thus in the case of some-

resale provides direct competition to new sales, threatening one having originally purchased a software application borne

profits to a greater degree than would be the case for a on a specific material object such as a DVD-ROM, the FSD

product that wears out over time. permits that person to resell that material object without

infringing the copyright associated with that application. In

What will be evident, we hope, is that the preceding obser- the case of a bitstring purchased online as a download, how-

vations presuppose a conception of digital objects that ever, the situation is rather different, with the link between

explicitly recognizes bitstrings, and nonmaterial objects that bitstring and the material bearer on which it resides being

generally, as separate objects with their own distinct and significantly looser. For although a downloaded bitstring

characteristic properties. For it is these properties, in this case must be borne by a material bearer of some sort, in contrast to

their nonmaterial mode of being and non-degradability, that when it is purchased on an object such as a DVD-ROM, in the

the points above rely on. Such phenomena, in other words, case of a download there is no specific material object to

simply cannot be understood without the kind of ontological which the bitstring is inherently tied at the point of purchase.

distinctions we have been urging.

Two recent legal cases illustrate the issues that can arise as a

The second aspect of this case we want to highlight—the result (Hamilton 2015; Huguenin-Love 2014; Serra 2013;

disputed legal situation surrounding the resale of lawfully Soma and Kugler 2014). In January 2012, Capitol Records,

downloaded bitstrings—puts the spotlight on the material a music publishing company, sued ReDigi, an online inter-

bearers of bitstrings and some of the main translational mediary allowing users to buy and sell audio files previously

actions, particularly the uploading and downloading of files, downloaded from iTunes, for copyright infringement in the

associated with their online exchange. The two sides United States. In March 2013, the courts ruled in favor of

involved in these legal disputes are typically the inter- Capitol (Capitol Records LLC v. ReDigi Inc, U.S. District

mediaries, on one hand, who wish to facilitate trade, and the Court, Southern District of New York, 112-00095), finding

media and software publishing companies, on the other, who that ReDigi’s activities were not covered by the FSD and so

wish to prevent those in possession of lawfully downloaded violated the music publisher’s copyright. Central to the

bitstrings from reselling them. That the current situation is courts’ ruling was its interpretation of ReDigi’s online plat-

unsettled is hardly surprising since trade of this kind is form, whereby those who wish to resell an audio file first

relatively new and the technologies involved are still devel- upload that file to the ReDigi “Cloud Locker” (a remote

oping. There are also strong and conflicting economic server located in Arizona), from which it can then be sold to

interests involved, with the intermediaries as well as the and downloaded by a new purchaser. Although ReDigi’s

potential buyers and sellers of bitstrings standing to gain from software ensures that any uploaded file is removed from a

secondary trade, while, as we have already noted, the pub- user’s own computer, the courts deemed that uploading a file

lishing companies are at risk of erosion of their profits if to the Cloud Locker necessarily involves the creation of a new

reselling is allowed. material bearer of that file rather than the transfer of an

existing one. Since the creation of a new bearer violates the

The main legal principle at stake here is the First Sale Doc- copyright holder’s reproduction rights, the file stored on the

trine (FSD),8 a set of rules originating in the pre-digital era Cloud Locker is unlawful and not, therefore, subject to the

that limit a copyright owner’s exclusive right to distribute FSD. Thus any exchange of an audio file that takes place via

the ReDigi platform was judged unlawful.

8 The courts reached a quite different conclusion in an other-

The same principle is usually referred to as the Exhaustion Doctrine outside

of the United States. wise similar case heard in Europe. In 2012, the European

14 MIS Quarterly Vol. 43 No. 4/December 2019

Faulkner & Runde/Theorizing the Digital Object

Court of Justice considered a case brought by Oracle Inter- The legal aspects of this case also remind us of what is

national, a producer of enterprise software, against UsedSoft, arguably the single most important feature of the bitstring: its

a German firm trading online in pre-owned downloaded capacity to bear nonmaterial objects such as application pro-

application software. Like Capitol Records, Oracle argued grams, audio recordings, and text. Indeed, the legal situation

that the FSD did not apply to downloaded software, since its regarding secondary trade is itself likely to depend on the

resale over the Internet would necessarily violate copyright in particular type of nonmaterial object a bitstring bears, since

much the same way as in the ReDigi case. Yet in this case the different law(s) may apply to bitstring bearers of application

court found in favor of UsedSoft, on the grounds that the FSD software than apply to bitstring bearers of, for example,

did apply so long as the originally downloaded copy of the audio- or e-books. More broadly, this feature highlights that

software was deleted or rendered unusable (UsedSoft v. the demand for bitstrings is a derived one, arising from

Oracle, ECJ, C-128/11, subsequently confirmed by the demand for the nonmaterial object inscribed into a bitstring,

German Federal Supreme Court, 17 July 2014, IZR129/08; rather than for the bitstring itself, and where multiple layers

case note in English (2014)).9 While recognizing that resale of nonmaterial bearer may exist between the bitstring and the

would involve the creation of a new material bearer, the court ultimate object of value. It is this feature that has played, and

deemed this lawful reproduction by virtue of it being nec- will continue to play, such an important role in the shaping of

essary for the use of the software by its lawful owner. digital markets and in the impact of bitstrings generally, and

why it is so important to be clear about the distinct properties

As things stand, then, the U.S. and European rulings on online of the various kinds of objects involved and the relations in

trade in pre-owned bitstrings conflict on a fundamental point, which they stand to each other.

namely the legality or otherwise of the new material bearers

created as part of the process. These decisions, and the Although we have focused on secondary markets for bit-

resulting jurisdictional differences, are likely to have signi- strings, there are many other cases in which similar concep-

ficant consequences for issues ranging from publishers’ tual issues arise and for which our theory might offer an

distribution, license and maintenance models and how they appropriate foundation. One of these concerns the tendency

position themselves in regard to non-transfer restrictions, the among certain consumers to value physical versions of a

design of online platforms employed by intermediaries, all the given item—a magazine, audio recording, or film, say—more

way through to the perverse incentives they may create for highly than its digital variants, despite the advantages the