Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articol Tocuri Si OA

Uploaded by

niko55555Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Articol Tocuri Si OA

Uploaded by

niko55555Copyright:

Available Formats

871

Moderate-Heeled Shoes and Knee Joint Torques Relevant to

the Development and Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis

D. Casey Kerrigan, MD, MS, Jennifer L. Johansson, MS, Mary G. Bryant, MD, Jennifer A. Boxer, BA,

Ugo Della Croce, PhD, Patrick O. Riley, PhD

ABSTRACT. Kerrigan DC, Johansson JL, Bryant MG, HE POSSIBILITY THAT different types of shoe wear

Boxer JA, Della Croce U, Riley PO. Moderate-heeled shoes

and knee joint torques relevant to the development and pro-

T contribute to the development and/or progression of knee

osteoarthritis (OA) deserves consideration, because shoe wear

gression of knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; is a potentially controllable and easily modifiable factor for this

86:871-5. prevalent and disabling disease.1,2 We3 previously found that

Objective: To determine if women’s dress shoes with heels stiletto high-heeled shoes with heels averaging 2.5in (6.35cm)

of just 1.5in (3.8cm) in height increases knee joint torques, in height exaggerate knee external varus and flexor torques

which are thought to be relevant to the development and/or during walking—torques that are thought to be relevant to the

progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA) in both the medial and development and/or progression of knee OA. Specifically, we

patellofemoral compartments. showed an increase in varus torque during walking with high-

Design: Randomized controlled trial. heeled shoes. This increase implies exaggerated compressive

Setting: A 3-dimensional motion analysis gait laboratory. forces through the medial aspect of the knee,4-6 the typical

Participants: Twenty-nine healthy young women (age, tibiofemoral site for knee OA.7 An increased varus torque is

26.7⫾5.0y) and 20 healthy elderly adult women (age, likely to be clinically significant, given animal data showing

75.3⫾6.5y). that increasing knee varus torque leads to degenerative changes

Interventions: Not applicable. in the knee’s medial compartment.8 Because repetitive loading

Main Outcome Measures: Peak external varus knee torque is believed to be an important etiologic factor in the develop-

in early and late stance and prolongation of flexor knee torque ment of OA, and walking is by far the most common daily

in early stance. Three-dimensional data on lower-extremity activity causing the greatest force about the knee,6 an increase

torques and motion were collected during walking while (1) in varus torque is likely to be important.

wearing shoes with 1.5-in high heels and (2) wearing control Similarly, we showed a prolongation of the knee flexor

shoes without any additional heel. Data were plotted and qual- torque in early to midstance, implying increased work of the

itatively compared; major peak values and timing were statis-

quadriceps muscles,4,9,10 increased strain through the patella

tically compared between the 2 conditions using paired t tests.

Results: Peak knee varus torque during late stance was tendon, and increased pressure across the patellofemoral

statistically significantly greater with the heeled shoes than joint.11 During walking, the increased strain that occurs

with the controls, with increases of 14% in the young women through the patella tendon, with its associated patellofemoral

and 9% in the elderly women. With the heeled shoes, the early pressures, may be important with respect to the development of

stance phase knee flexor torque was significantly prolonged, by degenerative joint changes within the patellofemoral compart-

19% in the young women and by 14% in elderly women. Also, ment. A study12 comparing women’s wide-based high-heeled

the peak flexor torque was 7% higher with the heeled shoe in shoes with narrow-based high-heeled shoes (each with an av-

the elderly women. erage heel height of 2.8in [7.1cm]) found that both types of

Conclusions: Even shoes with moderately high heels (1.5in) shoes exaggerated the knee varus torques (by an increase of

significantly increase knee torques thought to be relevant in the 26%) and the sagittal torques (by an increase in peak torque of

development and/or progression of knee OA. Women, partic- 30%).

ularly those who already have knee OA, should be advised Having learned that shoes with heels averaging 2.5 to 2.8in

against wearing these types of shoes. in height significantly increase knee joint torques, we hypoth-

Key Words: Biomechanics; Gait; Kinetics; Knee; Osteoar- esized that even moderately high heels would increase these

thritis; Rehabilitation; Shoes; Women. knee joint torques for the reasons noted previously3,12: that the

© 2005 by American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine shoe’s heel so compromises foot and ankle kinetics that bio-

and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and mechanic compensations to maintain stability and forward

Rehabilitation progression during walking must occur at the knee. Many

women, both young and old, continue to wear shoes with

moderately high heels that are less than 2in (5.1cm) high, in the

belief that these are sensible shoes. In fact, it is typically

From the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of

Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (Kerrigan, Bryant, Boxer, Della Croce, Riley); Spaul-

recommended that shoes with heels less than 2in are safe to

ding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA (Johansson); and Department of Biomed- wear.13,14 We have observed in our clinical experience that

ical Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy (Della Croce). even women who already have knee OA often wear dress shoes

Supported by the Ellison Foundation and by the Public Health Service (grant no. with heels (that are typically wide) that are slightly less than

NIH HD01351).

No party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article

2in high. We hypothesized that dress shoes with heels only

has or will confer a benefit on the author(s) or on any organization with which the 1.5in (3.8cm) high significantly increase the same knee joint

author(s) is/are associated. torques believed to be relevant to the development and/or

Reprint requests to D. Casey Kerrigan, MD, MS, Dept of Physical Medicine and progression of knee OA. To test our hypothesis, we used

Rehabilitation, University of Virginia School of Medicine, 545 Ray C Hunt Dr,

Charlottesville, VA 22908, e-mail: dck7b@virginia.edu.

standard 3-dimensional gait analysis techniques, commonly

0003-9993/05/8605-9141$30.00/0 used in gait laboratories, to evaluate joint torques and motion at

doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.018 the knee.12,15-20

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 86, May 2005

872 MODERATE-HEELED SHOES AND KNEE JOINT TORQUES, Kerrigan

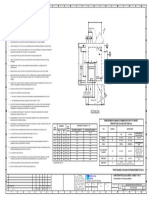

Fig 1. Custom shoes, size 9, with (A) moderate heel (1.5-in heel height) and (B) no heel (control).

METHODS newton meters per kilogram meters (Nm/kg-m). Sagittal knee

Healthy, able-bodied young (age, 18 –35y) and elderly (age, joint angle motion was also studied and was reported in de-

⬎65y) women were studied. We posted fliers to recruit sub- grees.

jects from the general population. Subjects had to be accus- Knee joint torque and sagittal plane motion data were

tomed to walking while wearing shoes with 1.5-in heels and graphed over the walking cycle (0%–100%). Averaged torque

not suffer from musculoskeletal, cardiac, or pulmonary disease. values (in the sagittal, coronal, and transverse planes) and

The study protocol was approved by both the institutional motion values (in the sagittal plane) for each subject for both

review board where the data were collected and by the insti- conditions were obtained from 3 trials (average of both right

tutional review board where the data were analyzed. Written and left lower extremities, providing an average of 6 values for

informed consent was obtained from each subject. Each subject each condition). We used a Student paired t test for both the

was asked to walk at her comfortable walking speed across a young group and the elderly group to compare knee torque and

10-m gait laboratory walkway under 2 conditions: with 1.5-in– motion values between the 2 conditions. Specifically, in the

heeled shoes and with control shoes, the order of which was coronal plane, we examined peak knee varus torques in both

randomized. early and late stance phases. We also examined prolongation of

Both the heeled and control shoes were custom-made by the sagittal flexor knee torque, calculating the time from initial

Lerness Shoes.a The heeled shoes (fig 1A) had a consistent contact until the sagittal torque became extensor as a percent-

1.5-in heel height across all sizes, and the control shoes (fig 1B) age of the gait cycle. Although the peak knee varus torques and

had zero heel height. All shoes had an identical upper and the timing of the knee flexor torque were our main variables of

midsole design. Although we previously found no difference in interest, we also evaluated the peak knee flexor torque during

effect of knee torques between wide- and narrow-heeled early stance, peak internal rotation torque, and peak knee

shoes,12 we decided to use a shoe with a wide heel in this study, flexion in stance and in swing. Applying a Bonferroni adjust-

because this style is conventionally believed to be especially ment for the use of multiple t tests, 3 variables in 2 groups, we

sensible and is commonly worn by both young adult and defined statistical significance at P less than .008 (.05/6).

elderly women. Subjects were fitted with test shoes by the

study staff based on the subject’s self-reported size. The sub- RESULTS

jects practiced walking with each test shoe to assure adequate A total of 50 subjects, 30 healthy young women and 20

fit and comfort and to become accustomed to the shoe. healthy elderly subjects, were assessed and found eligible for

Knee joint torque data in 3 planes (sagittal, coronal, trans- the study. One young subject was excluded from the final

verse) were collected bilaterally, over 3 trials, for each of the 2 analysis because of technical problems with her data set. Fur-

conditions. The procedures are based on standard techniques ther, 1 young and 3 elderly subjects were not included in the

reported elsewhere.3,12,15,16,19,21,22 We used a 6-camera video- analysis of knee flexor torque prolongation. Thus, most of the

based motion analysis system (Vicon 512 system)b to measure results reflect the analysis of data from 29 young and 20 elderly

the 3-dimensional position of 15-mm diameter markers, at 120 subjects, with a subgroup of 28 young and 17 elderly women

frames per second. Markers were attached to the following for the analysis of knee flexor torque prolongation. The young

bony landmarks on the pelvis and lower extremities during women averaged (mean ⫾ standard deviation [SD]) 26.7⫾5.0

walking: the bilateral anterior and posterior superior iliac years in age, 1.65⫾0.06m in height, and 58.7⫾8.99kg in body

spines, lateral femoral condyles, lateral malleoli, and forefeet. mass. The elderly women averaged 75.3⫾6.5 years in age,

Additional markers attached to lateral wands were placed over 1.60⫾0.07m in height, and 63.4⫾13.3kg in body mass. There

the midfemur and midshank. Ground reaction forces were was no significant difference in walking speed between the

measured synchronously with the motion analysis data using 2 heeled-shoe and control-shoe conditions for either the young

staggered force platformsc imbedded in the walkway. Joint women (1.32⫾0.13m/s and 1.32⫾0.12m/s, respectively;

torques in each plane were calculated by a commercially avail- P⫽.990) or the elderly adult women (1.25⫾0.15m/s and

able full-inverse dynamic model.b Accordingly, joint torque 1.25⫾0.16m/s, respectively; P⫽.768). The elderly women

calculations were based on 3 things: (1) the mass and inertial walked more slowly in both conditions, as would be expected,

characteristics of each lower-extremity segment, (2) the de- but the differences were not significant (control shoe, P⫽.069;

rived linear and angular velocities and accelerations of each heeled shoe, P⫽.089).

lower-extremity segment, and (3) the ground reaction force and The torque values (mean ⫾ SD) and P values for compari-

joint center position estimates. Joint torques, normalized for sons between heeled and control shoes, for young adult and

body weight and overall barefoot height, were reported in elderly women, are listed in table 1. Graphs of the coronal

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 86, May 2005

MODERATE-HEELED SHOES AND KNEE JOINT TORQUES, Kerrigan 873

Table 1: Knee Torque Parameters

Young Women Elderly Women

Parameters Heeled Shoes Control Shoes P* Heeled Shoes Control Shoes P*

Peak varus torque, early stance (Nm/kg-m) 0.33⫾0.07 0.32⫾0.06 .021 0.33⫾0.07 0.31⫾0.07 .001

Peak varus torque, late stance (Nm/kg-m) 0.25⫾0.05 0.22⫾0.05 ⬍.001 0.25⫾0.05 0.23⫾0.05 ⬍.001

Flexor torque prolongation (% gait cycle) 31⫾4.4 26⫾3.8 ⬍.001 33⫾3.3 29⫾4.4 ⬍.001

Peak flexor torque, early stance (Nm/kg-m) 0.28⫾0.11 0.28⫾0.11 .490 0.31⫾0.10 0.29⫾0.11 .007

Peak internal rotation torque (Nm/kg-m) 0.11⫾0.02 0.11⫾0.02 .104 0.10⫾0.03 0.10⫾0.03 .319

NOTE. Values are mean ⫾ SD.

*Applying a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests; P⬍.008 is significant.

(varus) knee torque with heeled and control shoes, averaged subjects and 19 of 20 elderly subjects showed an increase in

over the gait cycle, are illustrated in figure 2A (young women) either the early stance (not significantly increased) or late

and figure 2B (elderly women). Similarly, graphs of the sagittal stance (significantly increased) peak knee varus torque when

knee (flexor and extensor) torque with heeled and control shoes wearing heels. In 21 young and 14 elderly subjects, both varus

are illustrated in figure 3A (young women) and 3B (elderly torque peaks increased with heels.

women). The peak knee varus torque in late stance was signif- In 1 young woman and 3 elderly women, the sagittal knee

icantly greater for the heeled shoe compared with the control torque remained flexed with the heeled shoe throughout the

shoe for both the young and elderly women. The rate of entire stance period. These subjects were excluded from the

occurrence of increased late stance knee varus torque was quite analysis of flexor torque prolongation, because an appropriate

high, with 24 of 29 young and 16 of 20 elderly subjects. The value for crossover time could not be assigned. For the remain-

early stance peak knee varus torque was not significantly ing subjects, the sagittal knee flexor torque was prolonged with

higher in either group when the Bonferroni adjustment was heeled shoes in both the young and elderly women.

applied. Although the increase in early stance varus torque was Among the other variables evaluated there were some inci-

not significant, 22 young subjects and 16 elderly subjects dental findings of interest. The peak sagittal knee flexor torque

showed an increase in this peak value. Twenty-six of 29 young

Fig 2. Knee varus torque during walking plotted over an averaged Fig 3. Knee sagittal torque during walking plotted over an averaged

gait cycle. Effect of moderate-heeled shoe (solid line) versus control gait cycle. Effect of moderate-heeled shoe (solid line) versus control

shoe (dotted line) in (A) young women and (B) elderly women. shoe (dotted line) in (A) young women and (B) elderly women.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 86, May 2005

874 MODERATE-HEELED SHOES AND KNEE JOINT TORQUES, Kerrigan

was significantly greater for the heeled shoe than for the control motion and torques,27 it is important to note that even though

shoe for the elderly women but not for the young. No signif- subjects chose their own comfortable walking speeds, they

icant differences existed in peak internal rotation torque in late tended to walk at similar speeds with the heeled and control

stance in either group. Knee flexion angle in early stance was shoes.

greater with the heeled shoe in the elderly women (16°⫾5° vs The methods used in this study are considered to be the best,

14°⫾6°, P⫽.003) but not in the young women (15°⫾4° vs most technologically advanced, noninvasive techniques avail-

15°⫾4°, P⫽.758). Peak knee flexion angle in swing was re- able to assess biomechanics during walking. Nevertheless, a

duced with the heeled shoe in both young women (59°⫾3° vs limitation of our study, and of noninvasive gait analysis in

63°⫾3°, P⬍.001) and elderly women (57°⫾4° vs 61°⫾4°, general, is that we must infer rather than measure directly the

P⬍.001). joint contact forces from the measured net joint torques. Bio-

DISCUSSION mechanic modeling has shown that differences in net knee

As hypothesized, the late stance peak varus knee torque varus torques are the major determinants of differences in

increased significantly with moderately high heels of 1.5in in medial and lateral compartment contact forces.4 Similarly, the

both young adult and elderly women. There was no significant knee extension torque determines patellofemoral contact

increase in the early stance peak knee varus torque, but an forces. Thus, it is appropriate that these torques, rather than the

increase occurred in over half the subjects in both groups. The net joint forces, become the focus in looking for the cause of

late stance varus torque was increased, with a magnitude of medial compartment and patellofemoral joint OA. However,

increase compared with the control shoe of 14% in the young the development of new procedures that directly assess joint

women and 9% in the elderly women. Although in prior studies forces about the patellofemoral interface and medial compart-

with higher heels (2.5- and 2.8-in height) we found 23% and ment of the knee would be useful in at least corroborating the

26% increases in both early and late stance peak knee varus joint torque information obtained using current methods.

moments, the increases found here with moderate-heeled shoes This study is the first to use a standard shoe for all subjects

are still clinically notable. Often an aim of rehabilitation in to wear, rather than relying on the shoes that the subjects

patients with medial knee OA is to reduce the knee varus normally wore. This approach allowed us to construct and use

torque, to reduce the medial compartment loading. For in- a control shoe with no heel. (In previous studies, we used

stance, a lateral shoe wedge is often prescribed for patients barefoot walking as the control.) The advantage of the design

with medial compartment OA and has been reported to help in our study was that we could evaluate more purely the effect

reduce symptoms of knee OA.23,24 We25 showed that a 5° of the added heel. We28 previously showed that men’s sneakers

lateral shoe wedge reduces knee varus torque by a significant and dress shoes with an average 0.5-in heel do not, in men,

5% and 7% in early and late stance, respectively. Crenshaw exaggerate knee joint torques compared with walking barefoot.

et al26 similarly found in subjects with no knee OA that a lateral Thus, it is likely that shoes with heels up to 0.5in high do not

shoe wedge reduces knee varus torque by approximately 7%. significantly affect knee joint torques in women; however, it is

This amount of change is of similar magnitude to what we unknown what effect of heels between 0.5 and 1.5in high may

found in this study, albeit in an opposite direction. have on knee joint torques. Moreover, it is unclear what type of

Also as hypothesized, we found a significant prolongation of relation exists between heel height and knee torques at higher

the early external knee flexor torque. Although the heeled heel heights. Future study should include varying heel heights

shoes were associated with prolongation of the knee flexor across a wide range using a controlled shoe design. This

torque throughout the entire stance period in 1 young woman approach would show whether a relation, linear or otherwise,

and 3 elderly women, the characteristic early peak knee flexor exists between heel height and knee torques. Such a study

torque was prolonged by 19% and 14% in the remaining young would require special fabrication of shoes over a range of heel

and elderly women, respectively. Further, in the elderly women heights, controlled for design of everything except heel height.

the heeled shoe was associated with a significant 7% increase This is an expensive and time-consuming endeavor, requiring

in peak knee flexor torque. Although the magnitudes are different lasts to be made for each heel height. Nonetheless,

smaller, these findings are similar to those we found previ- knowing the precise relation between heel height and knee joint

ously: with stiletto 2.5-in high-heeled shoes knee flexor torque torques would allow proper epidemiologic studies to evaluate

is prolonged but there is no increase in the peak torque,3 and the effect of heel height on the predisposition for knee OA.

with the narrow and wide 2.8-in high-heeled shoes peak torque Having precise biomechanic data to guide epidemiologic stud-

is both prolonged and increased.12 ies is essential, because women tend to wear shoes with vary-

The current study is the first on the effects of shoes on knee ing heel heights that likely have varying effects on knee joint

biomechanics that has included a group of elderly women with torques. Future epidemiologic studies also must consider the

ages similar to those with knee OA. The heeled shoes had length of time and conditions under which different heel

essentially the same effect in the elderly women as in the young heights are worn.

adult women, with 2 additional effects in the elderly women.

One was the increase in peak knee flexor torque, already noted

above. The second was an increase in peak knee flexion in CONCLUSIONS

stance, which is likely related to the increased knee flexor Shoes with heels 1.5in high significantly increase peak ex-

torque. Although the reason for these age-related differences is ternal varus knee torque in late stance and prolong knee flexor

not clear, it is clear that overall, the elderly women’s knee torque in early to midstance. These are the same knee joint

biomechanics were affected by the heeled shoes to the same torques believed to be related to the development and/or pro-

degree as the younger women, if not more so. gression of knee OA. Our findings show that even moderately

As was observed with the higher-heeled shoes, we found in high-heeled shoes cause alterations in knee joint torques that

this study no changes in internal rotation torque. Also as are similar to those caused by women’s dress shoes with heel

observed with the higher-heeled shoes, we found here a reduc- heights averaging 2.5 and 2.8in. Women, particularly those

tion in peak knee flexion in swing in both the young and elderly who already have knee OA, should be advised against wearing

women. Because speed can affect the magnitude of both joint these types of shoes.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 86, May 2005

MODERATE-HEELED SHOES AND KNEE JOINT TORQUES, Kerrigan 875

References 16. Winter DA. Biomechanics and motor control of human move-

1. Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ. Defining arthritis and ment. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990.

measuring functional status in elders: methodological issues in the 17. Gage JR. Gait analysis. An essential tool in the treatment of

study of disease and physical disability. Am J Public Health cerebral palsy. Clin Orthop 1993;May(288):126-34.

1990;80:945-9. 18. Kerrigan DC, Glenn MB. An illustration of clinical gait laboratory

2. Verbrugge LM. Women, men, and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care use to improve rehabilitation management. Am J Phys Med Re-

Res 1995;8:212-20. habil 1994;73:421-7.

3. Kerrigan DC, Todd MK, Riley PO. Knee osteoarthritis and high- 19. Meglan D, Todd F. Kinetics of human locomotion. In: Rose J,

heeled shoes. Lancet 1998;351:1399-401. Gamble JG, editors. Human walking. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams

4. Schipplein OD, Andriacchi TP. Interaction between active and & Wilkins; 1994. p 73-99.

passive knee stabilizers during level walking. J Orthop Res 1991; 20. O’Connell PG, Siegel KL, Kepple TM, Stanhope SJ, Gerber LH.

Forefoot deformity, pain, and mobility in rheumatoid and nonar-

9:113-9.

thritic subjects. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1681-6.

5. Sharma L, Hurwitz DE, Thonar EJ, et al. Knee adduction moment,

21. Kerrigan DC, Riley PO, Nieto TJ, Croce UD. Knee joint torques:

serum hyaluronan level, and disease severity in medial tibiofemo-

a comparison between women and men during barefoot walking.

ral osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1233-40. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:1162-5.

6. Morrison JB. The mechanics of the knee joint in relation to normal 22. Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of

walking. J Biomech 1970;3:51-61. lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res

7. Windsor RE, Insall JN. Surgery of the knee. In: Sledge CB, Ruddy 1990;8:383-92.

S, Harris ED, Kelley WN, editors. Arthritis surgery. Philadelphia: 23. Sasaki T, Yasuda K. Clinical evaluation of the treatment of

WB Saunders; 1994. p 794-817. osteoarthritic knees using a newly designed wedged insole. Clin

8. Ogata K, Whiteside LA, Lesker PA, Simmons DJ. The effect of Orthop 1987;Aug(221):181-7.

varus stress on the moving rabbit knee joint. Clin Orthop 1977; 24. Yasuda K, Sasaki T. The mechanics of treatment of the osteoar-

Nov-Dec(129):313-8. thritic knee with a wedged insole. Clin Orthop 1987;Feb(215):

9. Winter DA. The biomechanics and motor control of human gait: 162-72.

normal, elderly and pathological. 2nd ed. Waterloo (ON): Univ 25. Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Goggins J, Merriman GJ, Kaplan RJ,

Waterloo Pr; 1991. Felson DT. Effectiveness of a lateral-wedge insole on knee varus

10. Perry J. Gait analysis: normal and pathological function. Thoro- torque in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med

fare: Slack; 1992. Rehabil 2002;83:889-93.

11. Reilly DT, Martens M. Experimental analysis of the quadriceps 26. Crenshaw SJ, Pollo FE, Calton EF. Effects of lateral-wedged

muscle force and patello-femoral joint reaction force for various insoles on kinetics at the knee. Clin Orthop 2000;Jun(375):185-92.

activities. Acta Orthop Scand 1972;43:126-37. 27. Lelas J, Merriman G, Riley P, Kerrigan D. Predicting peak kine-

12. Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Karvosky ME. Women’s shoes and knee matic and kinetic parameters from gait speed. Gait Posture 2003;

osteoarthritis [letter]. Lancet 2001;357:1097-8. 17:106-12.

13. Your podiatric physician talks about women’s feet. Information 28. Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Karvosky ME, Riley PO. Men’s shoes and

from the American Podiatric Medical Association. Available at: knee joint torques relevant to the development and progression of

http://www.apma.org/topics/womens.htm. Accessed September knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:529-33.

27, 2004.

14. Ebbeling CJ, Hamill J, Crussemeyer JA. Lower extremity me- Suppliers

chanics and energy cost of walking in high-heeled shoes. J Orthop a. Lerness Shoes, 2155 SW 8th St, Miami, FL 33135.

Sports Phys Ther 1994;19:190-6. b. Oxford Metrics Ltd, 14 Minns Estate, West Way, Oxford OX2 0JB,

15. Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME, Gainey J, Gorton G, UK.

Cochran GV. Repeatability of kinematic, kinetic, and electromyo- c. Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc, 176 Waltham St, Water-

graphic data in normal adult gait. J Orthop Res 1989;7:849-60. town, MA 02472.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 86, May 2005

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Music 10 (2nd Quarter)Document8 pagesMusic 10 (2nd Quarter)Dafchen Villarin MahasolNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Mortality - A Community ApproachDocument13 pagesNeonatal Mortality - A Community ApproachJalam Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Export Management EconomicsDocument30 pagesExport Management EconomicsYash SampatNo ratings yet

- Determination Rules SAP SDDocument2 pagesDetermination Rules SAP SDkssumanthNo ratings yet

- Cisco BGP ASPATH FilterDocument115 pagesCisco BGP ASPATH FilterHalison SantosNo ratings yet

- National Anthems of Selected Countries: Country: United States of America Country: CanadaDocument6 pagesNational Anthems of Selected Countries: Country: United States of America Country: CanadaHappyNo ratings yet

- The Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahDocument10 pagesThe Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahTyler FranklinNo ratings yet

- Lecture 14 Direct Digital ManufacturingDocument27 pagesLecture 14 Direct Digital Manufacturingshanur begulaji0% (1)

- Notes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0MDocument1 pageNotes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0Mسجى وليدNo ratings yet

- Jackson V AEGLive - May 10 Transcripts, of Karen Faye-Michael Jackson - Make-up/HairDocument65 pagesJackson V AEGLive - May 10 Transcripts, of Karen Faye-Michael Jackson - Make-up/HairTeamMichael100% (2)

- Sociology As A Form of Consciousness - 20231206 - 013840 - 0000Document4 pagesSociology As A Form of Consciousness - 20231206 - 013840 - 0000Gargi sharmaNo ratings yet

- 22 Khan S.Document7 pages22 Khan S.scholarlyreseachjNo ratings yet

- CV & Surat Lamaran KerjaDocument2 pagesCV & Surat Lamaran KerjaAci Hiko RickoNo ratings yet

- Chapter - I Introduction and Design of The StudyDocument72 pagesChapter - I Introduction and Design of The StudyramNo ratings yet

- Global Divides: The North and The South: National University Sports AcademyDocument32 pagesGlobal Divides: The North and The South: National University Sports AcademyYassi CurtisNo ratings yet

- Close Enough To Touch by Victoria Dahl - Chapter SamplerDocument23 pagesClose Enough To Touch by Victoria Dahl - Chapter SamplerHarlequinAustraliaNo ratings yet

- Aluminum PorterDocument2 pagesAluminum PorterAmir ShameemNo ratings yet

- World Insurance Report 2017Document36 pagesWorld Insurance Report 2017deolah06No ratings yet

- W25509 PDF EngDocument11 pagesW25509 PDF EngNidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- An Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyDocument312 pagesAn Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyGeetika CnNo ratings yet

- Apexi Powerfc Instruction ManualDocument15 pagesApexi Powerfc Instruction ManualEminence Imports0% (2)

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Information and Communication Technology 0417/13 May/June 2022Document15 pagesCambridge IGCSE™: Information and Communication Technology 0417/13 May/June 2022ilovefettuccineNo ratings yet

- Reported SpeechDocument6 pagesReported SpeechRizal rindawunaNo ratings yet

- Chhay Chihour - SS402 Mid-Term 2020 - E4.2Document8 pagesChhay Chihour - SS402 Mid-Term 2020 - E4.2Chi Hour100% (1)

- Promotion-Mix (: Tools For IMC)Document11 pagesPromotion-Mix (: Tools For IMC)Mehul RasadiyaNo ratings yet

- Sample Monologues PDFDocument5 pagesSample Monologues PDFChristina Cannilla100% (1)

- Rana2 Compliment As Social StrategyDocument12 pagesRana2 Compliment As Social StrategyRanaNo ratings yet

- Health Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyDocument3 pagesHealth Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyihealthmailboxNo ratings yet

- Fertilization Guide For CoconutsDocument2 pagesFertilization Guide For CoconutsTrade goalNo ratings yet

- Wner'S Anual: Led TVDocument32 pagesWner'S Anual: Led TVErmand WindNo ratings yet