Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Keperawatan

Keperawatan

Uploaded by

Febryananda PolapaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Keperawatan

Keperawatan

Uploaded by

Febryananda PolapaCopyright:

Available Formats

Short report

Home oxygen for children with acute bronchiolitis

S W Tie,1 G L Hall,2,3 S Peter,4 J Vine,4 M Verheggen,2 E M Pascoe,5 A C Wilson,2,3

G Chaney,1,3 S M Stick,2,3 A C Martin1,3

c Additional supplemental fig 1 ABSTRACT required oxygen therapy and satisfied all inclusion

is published online only at http:// A prospective randomised controlled pilot study was and exclusion criteria (table 1) were eligible.

adc.bmj.com/content/vol94/ performed comparing home oxygen therapy with tradi- Children were recruited over a single Australian

issue8

tional inpatient hospitalisation for children with acute bronchiolitis season, between 1 August 2007 and

1

Department of General bronchiolitis. Children aged 3–24 months with acute 30 November 2007.

Paediatrics, Princess Margaret

Hospital for Children, Perth,

bronchiolitis, still requiring oxygen supplementation 24 h

Western Australia; 2 Department after admission to hospital, were randomly assigned to Study protocol

of Respiratory Medicine, receive oxygen supplementation at home with support Families of eligible children (table 1) were

Princess Margaret Hospital for from ‘‘hospital in the home’’ (HiTH) or to continue oxygen

Children, Perth, Western approached and following informed consent chil-

supplementation in hospital. 44 children (26 male, mean dren were randomly assigned to continue tradi-

Australia; 3 School of Paediatrics

and Child Health, University of age 9.2 months) were recruited (HiTH n = 22) between tional inpatient care (hospital group) or to

Western Australia, Perth, 1 August and 30 November 2007. Only one child from continue oxygen therapy at home (hospital in the

Western Australia; 4 Ambulatory each group was readmitted to hospital and there were no home (HiTH) group). Researchers were blinded

Care Unit, Princess Margaret serious complications. Children in the HiTH group spent

Hospital for Children, Perth, and only following informed consent was the

Western Australia; 5 Clinical

almost 2 days less in a hospital bed than those managed management allocation revealed.

Research, Princess Margaret as traditional inpatients: HiTH 55.2 h (interquartile range Following randomisation children underwent a

Hospital for Children, Perth, (IQR) 40.3–88.9) versus in hospital 96.9 h (IQR 71.2– modified ‘‘safety in air test’’, designed to provide

Western Australia 147.2) p = 0.001. Home oxygen therapy appears to be a some degree of reassurance that if oxygen supple-

feasible alternative to traditional hospital oxygen therapy mentation were interrupted for an extended period

Correspondence to:

Dr A Martin, andrew.martin@ in selected children with acute bronchiolitis. the child would not develop sudden, life-threaten-

health.wa.gov.au ing hypoxia.6 The test involved continuous mon-

itoring of pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) levels

Accepted 26 September 2008 Acute bronchiolitis is a common reason for

and clinical status of the child, while in room air,

Published Online First hospitalisation in infants in developed countries,1

14 October 2008 over a period of 20 minutes. If SpO2 remained at

with treatment being essentially supportive.

80% or greater the child was considered to pass the

Although the need for supplemental oxygen is

test.

generally considered to be an absolute indication

Children randomly assigned to the hospital

for hospitalisation,2 Bajaj et al3 recently demon-

group had their weaning of supplemental oxygen

strated that children with acute bronchiolitis can

and the time of discharge from hospital managed

be managed safely with home oxygen therapy. The

by their paediatrician, independently of the study

broad application of this approach, however, has

investigators. Standard management of children

not been tested.

with acute bronchiolitis at our institution involves

The development of nurse-led, home-based care

supportive care only, with supplemental oxygen

has allowed children with a variety of illnesses to

therapy provided if SpO2 levels are less than 93%.

be managed safely at home rather than in

Parents of children randomly assigned to the

hospital.4 5 Whereas managing children with acute

HiTH group were assessed for suitability and

illnesses at home is not a new strategy, it is an

safety of providing care at home, were educated

increasingly attractive alternative to traditional

on home oxygen use and instructed on how to

inpatient hospitalisation. Home oxygen therapy

observe their children for signs of clinical deteriora-

is a well-accepted option for children with chronic

tion. Children were reviewed by a HiTH nurse

respiratory problems,6 but reports of home oxygen

within 12 h of hospital discharge and received a

therapy for children with acute respiratory pro-

minimum of two visits, in addition to one phone

blems are limited. We sought to determine the

contact with the parents in every 24-h period. At

feasibility and safety of home oxygen therapy for

each visit, if SpO2 was greater than 92%, oxygen

children with acute bronchiolitis compared with

was reduced as follows: 1 to 0.75 l/minute, 0.75 to

traditional inpatient hospitalisation.

0.5 l/minute, 0.5 to 0.25 l/minute, 0.25 to 0.125 l/

minute and 0.125 to 0.06 l/minute and SpO2

METHODS monitored for a further 15 minutes. If SpO2

Setting and subjects remained greater than 92% the child remained on

We conducted a prospective, randomised con- this oxygen flow until the next visit. Once the

trolled pilot study comparing home oxygen ther- child reached 0.06 l/minute a 15-minute trial in air

apy for children with acute bronchiolitis requiring was conducted and if SpO2 remained greater than

oxygen supplementation with traditional inpatient 92% the child was discharged.

hospitalisation. All children aged 3–24 months, Criteria for readmission to hospital were: (1)

admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital for Oxygen requirement increased to more than 1 l/

Children (PMH), Perth, Western Australia, with a minute to maintain SpO2 at greater than 92%; (2)

clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis, who apnoeic episode; (3) feeding less than 50% of

Arch Dis Child 2009;94:641–643. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.144709 641

Short report

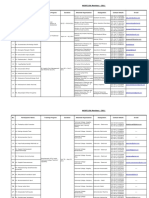

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria

3–24 Months of age (corrected gestation) Pre-existing cardiac, pulmonary (including chronic

lung disease of infancy, cystic fibrosis and

congenital or acquired airway anomalies) and

neuromuscular disorders

Clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis History of apnoea

Adequate feeding (>50% normal) and hydration Prematurity ,34 weeks’ gestation

Oxygen saturation .92% on (1 l/minute nasal cannula oxygen.

Observed and clinically stable for >24 h in hospital

Pass modified ‘‘safety in air test’’

Caregivers must be counselled about risk of smoking around a child receiving

oxygen supplementation

Caregivers must be adequately educated about home oxygen

HiTH nurses able to visit at home at least twice daily, in addition to daily phone

call

Paediatrician agrees that child is eligible for recruitment in study

HiTH, hospital in the home.

normal with clinical evidence of dehydration; (4) parents or with bacterial pneumonia requiring oxygen supplementation

treating paediatrician requested withdrawal of the child from and antibiotics. Both children made full and uneventful

the study. recoveries.

The primary outcome measure was readmission to hospital Children in the HiTH group spent significantly less time in a

within 7 days of discharge home and the secondary outcome hospital bed (55.2 h, IQR 40.3–88.9) than those in the hospital

measure was total days spent in a hospital bed. The study was group (96.9 h, IQR 71.2–147.2, p = 0.001). HiTH children

approved by the Princess Margaret Hospital Ethics Committee. received five (range four to 18) home visits from the time of

hospital to HiTH discharge, with two (range one to six) phone

contacts per patient.

Statistical analysis

A successful discharge was defined as not requiring readmission

to hospital within 7 days and a 10% difference in readmission DISCUSSION

rates between groups was considered to be clinically significant. This study suggests that home oxygen therapy is a feasible

Using a minimum success rate of 100% for the hospital group alternative to traditional hospital care in selected children with

and 90% for HiTH, we estimated that 180 children (90 in each uncomplicated acute bronchiolitis.

group) would be needed to demonstrate a difference, with 80% No differences in readmission rates between the HiTH and

power and 5% significance. Continuous data are expressed as hospital groups were noted, with only one of 22 (,5%) children

median (interquartile range; IQR) and group differences in each group readmitted. The present study is limited by its

compared with Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical data are small size, a result of funding and operational constraints.

shown as number (percentage) and compared with Fisher’s Whereas further studies with increased numbers are required,

exact tests. we believe that carefully selected children with acute bronch-

iolitis requiring oxygen therapy can be safely managed at home

by their parents with HiTH support.

RESULTS We demonstrated a significant reduction in the duration of

Forty-four of 58 eligible children were enrolled (table 2). Seven hospital admission in the HiTH group compared with hospital-

families were not approached as the children met the inclusion based care. This decreased length of stay may lead to

criteria outside normal working hours, four lived outside the improvements in service efficiency, including increased avail-

HiTH catchment area and three refused consent (see supple- ability of hospital beds at a time when the demand for resources

mental fig 1 available online only). is at a peak.

One child from each group (4.5%, 95% CI 0.1 to 22.8), In contrast to the study by Bajaj et al,3 we admitted all

required readmission to hospital. The child from the HiTH children to hospital for at least 24 h to ensure that they were

group was readmitted with dehydration secondary to viral feeding adequately and were clinically stable, a policy felt to be

gastroenteritis, with no change in respiratory status and was more acceptable to paediatricians. Furthermore, in the study by

managed with nasogastric rehydration and oxygen supple- Bajaj et al,3 primary care physicians supervised the weaning of

mentation. The child from the hospital group was readmitted oxygen, whereas this study utilised a nurse-led home-based

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of each group

Hospital group HiTH group p Value

No of children 22 22

Median age, months (range) 8.7 (3.0–18.0) 8.5 (3.0–17.6) 0.83

Males, n (%) 10 (45.4%) 16 (72.7%) 0.12

Oxygen saturation on ED arrival (median) 93% (81–99) 94% (88–99) 0.70

RSV positive 16 (72.7%) 11 (50%) 0.12

Parental smoking, n (%) 7 (31.8%) 6 (27.3%) 0.28

ED, emergency department; HiTH, hospital in the home; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

642 Arch Dis Child 2009;94:641–643. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.144709

Short report

service, a design more reflective of paediatric ambulatory care Competing interests: None.

services available in Australia and the UK. Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Princess Margaret Hospital Ethics

The lack of an effective treatment to change the natural Committee.

history of acute bronchiolitis means innovative approaches are Patient consent: Obtained.

required to decrease the health and economic burden of the

commonest cause of hospitalisation for infants in developed

REFERENCES

countries. Using carefully considered inclusion and exclusion 1. Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, et al. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations

criteria, home oxygen therapy is a feasible option in the among US children, 1980–1996. JAMA 1999;282:1440–6.

management of children with acute bronchiolitis. This practice 2. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Bronchiolitis in children: a

national clinical guideline. (SIGN publication no 91). NHS Quality Improvement

could potentially be established in any paediatric unit that is Scotland. November 2006.

supported by a nurse-led HiTH programme. 3. Bajaj L, Turner CG, Bothner J. A randomized trial of home oxygen therapy from the

emergency department for acute bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2006;117:633–40.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thanks the children and families who 4. Cooper C, Wheeler DM, Woolfenden SR, et al. Specialist home-based nursing

participated in the study, as well as the ambulatory care unit and general services for children with acute and chronic illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

paediatricians at Princess Margaret Hospital for Children. 2006;(4):CD004383.

5. Meates M. Ambulatory paediatrics – making a difference. Arch Dis Child 1997;76:468–73.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Western Australian State 6. Saletti A, Stick S, Doherty D, et al. Home oxygen therapy after preterm birth in

Health Research Advisory Council. Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2004;40:519–23.

Images in paediatrics

A plethoric palm

A 5-year-old boy presented with a red hand since birth. On

examination, his right palm was red, plethoric and slightly

larger when compared with his left palm (fig 1). A diffuse

capillary haemangioma of the right palm extending proximally

to involve the entire upper limb and the right pectoral region

was the cause for the marked plethora. Mild hypertrophy of

the right upper limb and a few tortuous veins over the right

pectoral region were noted (fig 2), and hence a diagnosis of

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome was considered. Klippel–

Trenaunay syndrome is a rare, sporadic, complex malformation

characterised by the clinical triad of (1) capillary malformations

(port wine stain), (2) soft tissue and bone hypertrophy or,

occasionally, hypotrophy of usually one lower limb and (3)

atypical, mostly lateral varicosity.1 Although lower-limb

involvement is very common among the patients with this Figure 2 Mild hypertrophy of the right upper limb and a few tortuous

syndrome, upper-limb involvement has been observed.2 The veins over the right pectoral region of the patient.

striking colour contrast of the palms and upper-limb involve-

ment make this case interesting.

B Adhisivam

Correspondence to: Dr B Adhisivam, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical

Education and Research, Pondicherry 605 006, India; adhisivam1975@yahoo.co.uk

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by MGMCRI.

Patient consent: Obtained from the parents.

Accepted 25 April 2009

Arch Dis Child 2009;94:643. doi:10.1136/adc.2009.164269

REFERENCES

1. Gloviczki P, Driscoll DJ. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: current management.

Phlebology 2007;22:291–8.

2. Akcali C, Inaloz S, Kirtak N, et al. A case of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome involving

Figure 1 Comparison of the patient’s left and right hand. only upper limbs. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2008;143:267–9.

Arch Dis Child August 2009 Vol 94 No 8 643

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- M1Document11 pagesM1Anthony Davis50% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Fetal Echocardiogram ProtocolDocument4 pagesFetal Echocardiogram Protocolapi-349402240No ratings yet

- Fraktur DentoalveolarDocument25 pagesFraktur DentoalveolarfirmansyahddsNo ratings yet

- Imp Gpat NotesDocument26 pagesImp Gpat Notespavan100% (1)

- DRUG STUDY OXYTOCIN, METHERGINE EtcDocument9 pagesDRUG STUDY OXYTOCIN, METHERGINE EtcPatricia Reese YutiamcoNo ratings yet

- Analytical Method Validation of Clopidogrel Tablets BR HPLCDocument48 pagesAnalytical Method Validation of Clopidogrel Tablets BR HPLCAman ThakurNo ratings yet

- Urology - House Officer Series, 5E (2013)Document336 pagesUrology - House Officer Series, 5E (2013)Diaha100% (1)

- Auto Urine TherapyDocument130 pagesAuto Urine TherapyBashu Poudel100% (3)

- Acne and RosáceaDocument692 pagesAcne and RosáceaMarcia Gerhardt MartinsNo ratings yet

- L10 LED Light Source IFUDocument48 pagesL10 LED Light Source IFUsongdashengNo ratings yet

- AD-210052-01-CT - B-MDR Comparison Table STERRAD Vs VPRO Max2 - TM - 2022Document1 pageAD-210052-01-CT - B-MDR Comparison Table STERRAD Vs VPRO Max2 - TM - 2022Abdessamad ZaherNo ratings yet

- Malaria Lesson Plan 1Document3 pagesMalaria Lesson Plan 1Jayshree ParmarNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Nursing Checklist NUR 3915 Clinical Practice V 4 (0+4)Document2 pagesBachelor of Nursing Checklist NUR 3915 Clinical Practice V 4 (0+4)Ching WeiNo ratings yet

- KMPDU Press ReleaseDocument1 pageKMPDU Press ReleaseKenneth NgethaNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies EssayDocument3 pagesLogical Fallacies Essayfz75nk7v100% (2)

- Relert Tablets: 1. Qualitative and Quantitative CompositionDocument9 pagesRelert Tablets: 1. Qualitative and Quantitative Compositionddandan_2No ratings yet

- AKOFE Life Members - 2011Document8 pagesAKOFE Life Members - 2011vasanthawNo ratings yet

- Note Guidance Use Stability Testing Human Medicinal Products - en PDFDocument3 pagesNote Guidance Use Stability Testing Human Medicinal Products - en PDFcindi saputriNo ratings yet

- Kit Insert MG PDFDocument2 pagesKit Insert MG PDFlatyfahNo ratings yet

- MastitisDocument13 pagesMastitisapi-232713902No ratings yet

- Statistical Manual For The Use of Institutions For The Insane Apa PDFDocument733 pagesStatistical Manual For The Use of Institutions For The Insane Apa PDFAlexandra SelejanNo ratings yet

- SBQuiz 3Document9 pagesSBQuiz 3Tran Pham Quoc ThuyNo ratings yet

- Injuries of Wrist and HandDocument34 pagesInjuries of Wrist and HandMugunthan Rangiah100% (1)

- Check-Up: Mahirap MagkasakitDocument5 pagesCheck-Up: Mahirap Magkasakitichu73No ratings yet

- Unit 6 Biomedical Waste ManagementDocument14 pagesUnit 6 Biomedical Waste ManagementjyothiNo ratings yet

- Label Elements of The CLP RegulationDocument10 pagesLabel Elements of The CLP RegulationSupriyaNo ratings yet

- Sicknessandfitnesscertificates PDFDocument6 pagesSicknessandfitnesscertificates PDFniraj_sdNo ratings yet

- CertificateDocument1 pageCertificateShashankNo ratings yet

- 02 HBC Block 3 ChallengesDocument3 pages02 HBC Block 3 Challengess1231939707No ratings yet

- AnalysisDocument20 pagesAnalysisajaysomNo ratings yet