Professional Documents

Culture Documents

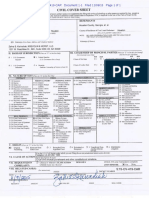

SCR

SCR

Uploaded by

everen0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views1 pagephisolophy very imprtant

Original Title

scr

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentphisolophy very imprtant

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views1 pageSCR

SCR

Uploaded by

everenphisolophy very imprtant

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

THE MIND’S AWARENESS OF ITSELF 117

nesses (i.e., experiences) of certain internal (non-mental) objects –

a chemical state of the blood, say? Just as we conceived of visual

experiences as internal states having the property of being aware-

nesses of P (for some P of an external o), why can’t hunger be

similarly conceived of as an internal experience (a p-awareness)

of the properties of an internal o? Why can’t an itch in one’s arm

be thought of not as something in the arm (brain?) one is o-aware

of, but an o-awareness (in the head) of a physical state of the arm?

Why can’t we, following Damasio (1994), conceive of emotions,

feelings, and moods as perception of chemical, hormonal, visceral,

and muscuoskeletal states of the body?

This way of thinking about pains, itches, tickles, and other bodily

sensations puts them in exactly the same category as the experiences

we have when we are made perceptually aware of our environment.

The only difference is that bodily sensations are the experiences

we have of objects in the body (the stomach, the head, the joints,

etc.), not objects outside the body. What gives these sensations their

phenomenal character, the qualities we use, subjectively, to indi-

viduate them, are the properties these experiences are experiences

of, the properties (of various parts of the body) that these experi-

ences make us p-aware of (irritation, inflammation, time of onset,

injury, strain, distension, intensity, chemical imbalance, and so on).

What gives a (veridical) visual experience of an orange pumpkin its

particularly quality ( ) are the qualities of the pumpkin (viz., P) that

this experience (in virtue of being ) is an experience of. Likewise,

what gives headaches their particular quality (what distinguishes

them from pains in the back, itches, thirst, anger or fear) are the

properties (and these include locational properties) that these exper-

iences are p-awarenesses of. Just as one becomes aware of external

objects in having visual and olfactory experiences, so one becomes

aware of various parts of the body (and the properties of these parts)

in having bodily sensations – e.g., pain. Having a headache is not an

awareness – certainly not an o-awareness – of a mental entity: a pain

in the head. The only awareness one has of pain is an f-awareness

that one has it. In saying that one feels pain what one is really saying

is not that one is o-aware of something mental (viz., a pain) – but

that one feels (is aware of) a part of the body the feeling (awareness)

of which is painful (is pain). Once again, the phenomenal qualities

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Invocation of LilithDocument4 pagesInvocation of Liliths.bheeshmar100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- PowerPoint Presentation For Data CenterDocument46 pagesPowerPoint Presentation For Data Centeryogesh chandrayan100% (1)

- Defects in PaintDocument6 pagesDefects in Paintsonu024100% (1)

- Pharmarack - IPM Diaries - Strategic Partnerships - May 2024Document42 pagesPharmarack - IPM Diaries - Strategic Partnerships - May 2024Shafi UllahNo ratings yet

- Presenter 6 - Puan Nor Hayati Abdul Rahim-PPT PKA 2Document38 pagesPresenter 6 - Puan Nor Hayati Abdul Rahim-PPT PKA 2Samantha SeeNo ratings yet

- Notifier 320 Operations ManualDocument76 pagesNotifier 320 Operations ManualYussef OrtizNo ratings yet

- Module 8Document28 pagesModule 8Rio TomasNo ratings yet

- PVP2000-PVP5200 Data Sheet PDFDocument2 pagesPVP2000-PVP5200 Data Sheet PDFRES SupplyNo ratings yet

- D Evaluation For Resective Epilepsy SurgeryDocument104 pagesD Evaluation For Resective Epilepsy SurgeryYusuf BrilliantNo ratings yet

- VHX 1420 Hfs PDFDocument2 pagesVHX 1420 Hfs PDFCarlos Eberhard Diaz Torres100% (1)

- Ah5f GaDocument2 pagesAh5f GaNelson P. ColoNo ratings yet

- Mil PRF 87100a PDFDocument12 pagesMil PRF 87100a PDFNadia SalemNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Cannabis Grows Using Fourier Transform Mid Infrared SpectrosDocument4 pagesOptimization of Cannabis Grows Using Fourier Transform Mid Infrared SpectrosTrelospapasse BaftisedenyparxeisNo ratings yet

- Bio-Dynamic Agriculture An IntroductionDocument266 pagesBio-Dynamic Agriculture An IntroductionTeo100% (1)

- Timothy Johnson DocumentDocument1 pageTimothy Johnson Document13WMAZNo ratings yet

- Nurses LE 11-2022Document242 pagesNurses LE 11-2022PRC Baguio33% (3)

- Executive Summary: K M F DDocument47 pagesExecutive Summary: K M F DUmesh AllannavarNo ratings yet

- Primary Water SystemDocument15 pagesPrimary Water SystemSantoshkumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Special EducationDocument44 pagesSpecial EducationNoman MasoodNo ratings yet

- 2001 - Mackenzie - VO2 MaxDocument9 pages2001 - Mackenzie - VO2 MaxHerdiantri SufriyanaNo ratings yet

- Shs Ucsp q2 Mod7 Human Responses To Emerging ChallengesDocument19 pagesShs Ucsp q2 Mod7 Human Responses To Emerging ChallengesJovele Octobre100% (2)

- Q2 Cookery 10 WK 1 8Document54 pagesQ2 Cookery 10 WK 1 8Maxine Eunice RocheNo ratings yet

- FSW-Tech Handbook For Specialists and Engineers - enDocument172 pagesFSW-Tech Handbook For Specialists and Engineers - enkamal touilebNo ratings yet

- DS0960205-0303860 Adapter Cable Camera BNC - 4pF A01Document2 pagesDS0960205-0303860 Adapter Cable Camera BNC - 4pF A01Игорь ИвановNo ratings yet

- Background Report For The National Dialogue On PaintDocument82 pagesBackground Report For The National Dialogue On PaintMSCT TrainingNo ratings yet

- Jharokha Menu New 1Document12 pagesJharokha Menu New 1aditya ganjuNo ratings yet

- R250 RegulatorDocument12 pagesR250 Regulatoremerson212121100% (2)

- FILL FINISH Solutions ENDocument32 pagesFILL FINISH Solutions ENSatish HiremathNo ratings yet

- All India Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited Executives' AssociationDocument1 pageAll India Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited Executives' AssociationKabul DasNo ratings yet

- Antonette Garcia ThesisDocument28 pagesAntonette Garcia ThesisRovhie Gutierrez BuanNo ratings yet